Abstract

Pharmaceutical legislation provides a legal framework to ensure the safe and effective use of medicines. This framework requires national regulatory authorities (NRAs) to establish and maintain a pharmacovigilance system (PV system) stating and enforcing the regulatory commitments that key stakeholders, including marketing authorisation holders (MAHs), are required to fulfil. In recent years, national legislative bodies and NRAs across the world have issued a significant amount of legislation and guidance enforcing the obligation to perform pharmacovigilance activities. In countries where the NRA is a member of the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH), safety management requirements are generally consistent with ICH guidelines. In a number of countries beyond this scope, requirements may deviate from internationally agreed standards, adding a substantial complexity and increasing burden on the stakeholders involved, whilst the benefit for patients’ safety may not be evident. Committed to fulfilling safety-regulatory obligations in any country where a product licence is held, global pharmaceutical companies have accumulated a broad and deep experience acquired whilst meeting the expectations of a large array of diverse PV systems across the world. These range from sub-optimal frameworks, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Benchmarking Tool, to highly effective resource-optimised PV systems. In order to support countries creating or further developing their PV systems, especially where infrastructure and resources are limited, the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) International Pharmacovigilance Group (IPVG) has developed consensus recommendations consistent with harmonised standards for the development and step-wise implementation of key PV system components. These recommendations endorsed by the EFPIA membership constitute the focus of this review article.

Similar content being viewed by others

An effective pharmacovigilance system requires partnership between multiple stakeholders, including national regulatory authorities (NRAs) and marketing authorisation holders, to achieve public health goals. |

As countries further enhance their pharmacovigilance systems, consideration needs to be given to the development of requirements that benefit patients, are well thought and are practical to implement. |

With an understanding of global pharmacovigilance systems and stakeholders, and local pharmacovigilance needs, pharmacovigilance experts from innovator pharmaceutical companies propose recommendations for consideration by NRAs as they further develop pharmacovigilance requirements in their country. |

1 Introduction

Pharmaceutical legislation provides a legal framework to ensure the availability of acceptably safe, effective and high-quality medicines to patients. One element of this framework mandates national regulatory authorities (NRAs) and marketing authorisation holders (MAHs) to establish and maintain pharmacovigilance systems (PV systems). These systems should be capable of detecting, assessing, understanding and preventing adverse effects or any other possible drug-related problems [1].

PV systems exist in many countries and regions worldwide, and may range from basic to well established, with numerous countries just in the process of developing PV systems.

The World Health Organization (WHO) supports the development of national PV systems by providing a Global Benchmarking Tool [2] to support NRAs in objectively evaluating their own regulatory system according to a maturity scale ranging from 1 (lowest) to 4 (highest). Maturity level 1 is the “existence of some elements of regulatory system” and level 4 is “operating at advanced level of performance and continuous improvement”. In addition, the WHO and the Global Fund have published guidance on the minimum requirements for a functional PV system [3].

In recent years, national legislative bodies and NRAs have issued a significant amount of legislation and guidance to provide a legal foundation and practical implementation guidance for national PV systems. Some new and evolving national frameworks align with international standards, but others have added significant complexity and breadth to pharmacovigilance requirements, placing avoidable burden on stakeholders without necessarily benefiting patients. Examples include email systems not able to cope with the volume of information sent by MAHs, duplication of data collection from global markets, and divergent risk-management plan (RMP) formats. In emerging markets, an overly complex and burdensome national PV system is unlikely to be sustainable, especially in countries where infrastructure and resources remain limited. In such a setting, a step-by-step development approach to building national pharmacovigilance infrastructure, moving from a core framework to advanced capacity may be more effective. In addition, regulatory reliance, i.e. the concept of relying on other NRAs’ outputs, work-sharing and joint assessments may support regulators as they evolve and refine their national PV systems and should be considered from the start [4].

2 Objective

The European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) International Pharmacovigilance Group (IPVG) is a European-based group of pharmacovigilance experts from innovator pharmaceutical companies operating across the various regions of the world. The group brings together a wealth of practical experience from operating under divergent pharmacovigilance legislation as well as diverse concepts and approaches to PV system development. The IPVG wishes to use this extensive experience to positively contribute to the development of efficient and more harmonised national PV systems, delivering the safest and most effective medicines to patients worldwide.

This document follows extensive discussions and presents the aligned view of the EFPIA-IPVG on key considerations for the development of effective national PV systems by NRAs as well as options for the pragmatic management of key components of these systems in countries where infrastructure and resources are limited.

The authors provide aligned recommendations for those PV system components, where a common global standard appears feasible. It is the authors’ hope that this document delivers a useful reference for interested stakeholders, particularly for NRAs currently developing or refining national PV systems for medicinal products in emerging markets.

3 Priorities when Establishing “Effective PV Systems”

Effective PV systems are primarily systems capable of detecting, assessing, understanding and preventing adverse effects or any other drug-related problems [1]. In resource-limited settings, such PV systems may be built step-by-step as per priorities and available resources, whilst effectively using the concept of reliance, i.e. relying and drawing on the experience and capabilities of a network of peer regulators and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and sharing regulatory standards and existing outputs of established systems.

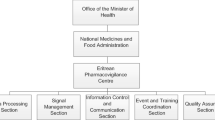

A clear and transparent organisational structure at the NRA level and an internationally accessible website providing relevant information not only in the local language but also in English for all relevant information may facilitate information exchange with MAHs operating in multiple countries and for NRAs practising regulatory reliance.

The IPVG considers three PV system elements essential to the effective set-up of a national PV system:

-

A national reporting system for suspected adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and information on medicinal product use in special situations (see Sect. 4)

-

Implementation of an efficient national system to communicate safety information to the public (see Sect. 7)

The ability to oversee suspected ADRs and information on medicinal product use in special situations is fundamental to the detection, assessment, understanding and mitigation of medicinal product risks. Various collection tools for such information are available depending on local needs and preferences, e.g. telephone hotlines, paper forms, websites and mobile applications such as the WEBRADR Mobile App (see the glossary in the Electronic Supplementary Material). Suspected ADRs need to be maintained in a safety database. To maximise use of limited resources, the IPVG recommends use of the WHO’s VigiFlow (see glossary) when not setting up a specific national database (see Sect. 4).

Further elements of a national PV system may include:

-

Requirements for the submission of periodic safety reports (see Sect. 8).

-

Requirements for the submission of RMPs (see Sect. 9)

-

Requirements for a written description of the MAH’s PV system (see Sect. 10)

-

Establishment of a Local Safety Responsible (LSR) (see Sect. 11)

The priority and the order in which each element may be added will depend on local needs, available resources and preferences in relying on outputs from other regulators, and the choice to use own or NGO-offered safety systems either temporally or permanently. Figure 1 shows a suggested order for establishing an effective PV system.

A successful reporting system requires public awareness. The IPVG recommends that global public awareness tools such as those provided by the Strengthening Collaboration for Operating Pharmacovigilance in Europe (SCOPE) initiative (see the glossary in the Electronic Supplementary Material) and by the Uppsala Monitoring Center (UMC) are used to increase public awareness and importance of ADR reporting. Educational material for healthcare professionals (HCPs) is also available via SCOPE and may be used for training of HCPs in university courses and beyond. It is recommended that public health campaigns centre around a specific public health initiative, e.g. a vaccination programme or an emergency medicine.

4 Individual Case Safety Report Management

The foundation of any national PV system is a national reporting system. Such a system facilitates the collection of adverse events (AEs) and information on medicinal product use in special situations from HCPs and consumers/patients, and the expedited reporting of suspected ADRs as individual case safety reports (ICSRs). ICSR data forms the basis of a national dataset for medicinal products. This dataset is constantly evolving based on the information received.

ICSR data also serve as the basis for the detection of safety signals, the review of the benefit–risk relationship in periodic safety reports, and risk management planning.

NRAs receiving ICSRs in an expedited manner, i.e. within specific timelines, should assess individual reports soon after receipt. If a significant public health concern is identified, the NRA should quickly take regulatory action to mitigate risks to patients.

The most accepted standards for pharmacovigilance come from the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH)Footnote 1 and the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS),Footnote 2 which has set many of the founding principles for pharmacovigilance, including the CIOMS-1 form for reporting suspected ADRs.

Table 1 outlines definitions for AEs and ADRs in accordance with the ICH E2D guideline on post-approval safety data management [5].

In addition to the collection of AEs, collection of information on medicinal product use in special situations [6] is required by many regulators for systematic safety surveillance. This information (see Table 2) can be collected in the same way as AEs.

ICSRs should be considered valid for expedited reporting only if the report contains the four minimal criteria as described in the ICH E2D guidance and in Table 3.

To support their national pharmacovigilance database, NRA members of the WHO Programme for International Drug Monitoring (WHO-PIDM) are entitled to use the VigiFlow system made available by the UMC, the WHO-associated centre for international drug monitoring. VigiFlow is an online platform, structured according to country-specific ICSR containers owned and controlled by the respective NRAs. VigiFlow includes functionality to let NRAs forward ICSRs to VigiBase (the global WHO pharmacovigilance database). In addition, any NRA contributing to the WHO-PIDM (using VigiFlow or not) has access to VigiBase to search for signals at country, regional or global levels, using VigiLyze, an advanced online analytic tool supplied by the UMC [7]. VigiLyze also allows a NRA to view foreign ICSRs as they relate to a search topic.

4.1 Domestic ICSR Management

The IPVG recommends that NRAs request MAHs to collect information on all domestic AEs as well as cases of parent–child exposure even if no AE occurred. Other domestic cases of exposure in special situations lacking the occurrence of any AE do not require expedited reporting, but should be compiled by the MAH and reported in the Periodic Benefit Risk Evaluation Report (PBRER). For expedited reporting, the following reporting timelines are recommended:

-

15 calendar days for serious ICSRs as per ICH E2D guidance.

-

90 calendar days for non-serious ICSRs as per European Union (EU) Good Vigilance Practice (GVP) Module VI (rev. 2).

4.2 Foreign ICSR Management

For access to foreign ICSRs, the IPVG recommends considering accessing the WHO’s VigiBase, the largest global pharmacovigilance database, currently containing over 20 million ICSRs, using the WHO’s VigiLyze software. VigiLyze is exclusively reserved for NRAs contributing to the WHO-PIDM, free of charge, and represents a powerful and resource-efficient alternative to the receipt of foreign ICSRs from MAHs. In addition, the VigiLyze data analytic tool can be used to perform signal detection and other analytic investigations at the country, regional or global level.

5 Signal Management

A medicinal product is authorised for marketing if the applicant can demonstrate sufficient evidence for quality, safety and efficacy in the specified indication(s) and target population(s). As the investigated clinical trial population is usually limited in size and duration of drug exposure, as well as selective for criteria such as age, gender, genetic variants, concomitant diseases and co-medication, not all ADRs and risks will be known at the time of the initial marketing authorisation. In fact, certain ADRs and risks can only be discovered or further characterised post-authorisation [8]. According to internally accepted standards and regulations, MAHs should therefore have continuous safety monitoring and signal management systems in place that permit early detection of potential new risks or potentially changed characteristics of known risks.

Signal management is defined as a set of activities performed to determine whether, based on an examination of ICSRs, aggregated data from active surveillance systems or studies, scientific literature information or other data sources, there are new risks associated with an active substance or a medicinal product or whether known risks have changed, as well as any related recommendations, decisions, communications and tracking [9]. Depending on the size of the dataset, different signal detection methodologies or combinations of methodologies may be used.

Review of global safety data should reside with experienced staff of the MAH that owns the global safety database for the medicinal product and who are in the position to oversee and analyse signals from all sources from the totality of the globally available dataset relevant to a given safety issue. If a MAH does not own or have access to the global safety database or lacks the expertise to conduct signal detection and analysis, the MAH may delegate some or all activity to the global safety database-owning organisation.

Review of national safety data for local signals by NRAs/national pharmacovigilance centres may contribute to understanding a medicinal product’s safety profile in the local market and may focus on, e.g. medication errors, off-label use, misuse, abuse or potential risks described in RMPs. Regional and/or global data may supplement local data as appropriate. For example, identified similarities of national data with regional or global data will further strengthen a local signal, whereas differences between national and regional/global data may help in identifying factors that are specific to a country/region and need to be considered when discussing appropriate local risk-minimisation measures. For reviewing pools of individual safety data, the IPVG recommends using VigiLyze for searching into the WHO pharmacovigilance database (VigiBase) to detect signals at the country level compared to searches at the regional or global levels.

NRAs may also consider networking with stakeholders or other NRAs for confirmation of their signal detection finding and/or use signal detection outcomes from established NRAs as surrogates for their own analyses.

6 Signal Reporting

Signal reporting from the MAH to NRAs should be proportionate to the information arising from the signal analysis. The IPVG proposes a risk-appropriate approach to signal reporting similar to recommendations made by the Swissmedic [10] and that those signals that require in-market action (e.g. product information update, direct market communication, marketing authorisation suspension/revocation/withdrawal for safety reasons) should be notified to an NRA in line with Table 4.

The IPVG also recommends using common terminology such as the terminology proposed by the CIOMS VIII working group [11] or EU-GVP Module IX [9] to avoid misunderstandings in reportability of signals to NRAs. The term “emerging safety issue” (ESI) [12] should only be used for the most serious risks where an immediate in-market action is required to protect patients and public health.

7 Safety Communication

Communicating safety information to patients and HCPs is a public healthcare responsibility and essential for achieving the objectives of pharmacovigilance in terms of promoting the rational, safe and effective use of medicines, preventing harm from adverse reactions, minimising risks and contributing to the protection of patients’ and public health [13].

Routine safety communication relates the provision of product safety information in a standardised format to HCPs and patients. Means of providing this information may differ at the local level depending on local needs and practices; however, the information should always reflect current knowledge of the benefit–risk profile of the medicinal product and be available to the public within reasonable regulatory timelines.

Non-routine safety communication may include direct communications to HCPs and safety alerts to the public via diverse media and should be the result of a thorough review of all available evidence, the choice of risk-proportionate actions and a coordinated action plan to communicate the information.

Whichever the communication method chosen, communication should always deliver clear messages describing any new risk in the context of the benefit of the medicinal product and be tailored to the relevant audience. A description of competing risks, such as risks of non-treatment, may also be appropriate. Any safety communication proposed by the MAH should be reviewed and approved by the concerned NRA.

8 Periodic Safety Reports

Periodic safety reports such as the EU Periodic Safety Update Report (PSUR) provide a review of the current benefit–risk profile of a medicinal product, taking into account all available worldwide data including:

-

Safety, efficacy and effectiveness data

-

Use of the medicinal product in authorised and non-authorised (“off-label”) indications

-

Missing data (e.g. data in special populations)

For a consistent global approach to the periodic evaluation of a medicinal product’s benefit–risk profile, the IPVG recommends the use of the PBRER format as outlined by the ICH E2C guidance [14].

The PBRER is very comprehensive, describing post-marketing data, data from completed and ongoing clinical trials, relevant non-interventional studies and other activities, cumulatively and for the specified report period, at a global level. The document also presents a comprehensive and critical analysis of new or emerging information on the risks of the medicinal product in the context of its benefits, taking into account new information from the last reporting period and cumulative information. The analysis of the risks is based on the reference safety information [15].

The International Birth Date (IBD) is the date of the first marketing authorisation for any medicinal product containing the active substance granted to an applicant in any country in the world. Using a single birth date such as the IBD and aligned review periods/data lock points (DLPs) for periodic safety reports worldwide is recommended, not only for harmonisation purposes and reduction of administrative burden, but also to facilitate true global periodic benefit–risk assessment for the medicinal product.

In addition, the IPVG recommends aligning the periodicities of existing country-specific periodic safety reports with the periodicities of the global benefit–risk assessments in the PBRERs to allow for direct comparability of local data with global data and the interpretation of local data in the context of available global data from all sources.

The PBRER should preferably be written in a commonly understood technical language, i.e. English, to allow for consistency and avoid translation errors. Should translations into national languages be required, a translation of the Executive Summary could be an effective approach, as it contains a summary of the key information contained in the document.

The frequency of report submission to NRAs depends on factors such as the length of time the medicinal product has been on the market, product-specific risks and the extent of knowledge regarding the product’s benefit–risk profile.

In general, PBRER periodicities and submission frequencies for newly authorised medicinal products in a country should follow ICH E2C and/or EU-GVP Module VII [16] recommendations and be based upon the DLP calculated from the IBD i.e. 6-month periodicity the first 2 years after approval, then annually for the subsequent 3 years.

When a newly authorised medicinal product in a country already has a marketing authorisation in a reference country, the IPVG recommends alignment with the periodicity and submission frequency for the medicinal product in the reference country or alignment with the periodicity and submission frequency as described in the European Union Reference Dates (EURD) list (see the glossary in the Electronic Supplementary Material).

The IPVG recommends harmonised timelines for PBRER preparation and submission according to internationally acceptable timelines such as:

-

Within 70 calendar days of the DLP for PBRERs covering intervals up to 12 months.

-

Within 90 calendar days of the DLP for PBRERs covering intervals in excess of 12 months.

Furthermore, the IPVG would like to mention that the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has a EU-GVP for PSUR assessment report (PSUSA) procedureFootnote 3 in place where one EU member state ensures a coordinated single assessment for medicinal products that contain the same active substance or combination of active substances. The PSUSA procedure is an excellent example of resource-effective regulatory reliance advocated earlier.

9 Risk Management Plans

Marketing authorisation applicants may be required by NRAs to submit RMPs, which include essential information on a medicinal product’s safety profile and prospective plans for pharmacovigilance activities designed to gain greater knowledge of both known risks and risks potentially associated with the medicinal product. RMPs also describe risk-minimisation measures for important risks (e.g. updates to product information, direct HCP communication, or pregnancy prevention programmes where a medicinal product may have teratogenic effects) and the evaluation of the effectiveness of risk-minimisation activities.

In the EU, the EU-RMP format in accordance with EU-GVP Module V [8] provides the most comprehensive document to date on medicinal product-specific pharmacovigilance activity planning and proactive risk management.

It contains:

-

A summarised safety specification relating to cumulative globally available data from pre-clinical, clinical and post-marketing experience, epidemiological information relevant for the disease and the indication.

-

The important risks and any missing information on the benefit–risk profile for the medicinal product.

-

Routine and additional pharmacovigilance activities.

-

Routine and additional risk-minimisation measures needed.

The EU-RMP routinely undergoes a robust assessment by EU regulators for scientific evidence and appropriateness of pharmacovigilance activities and risk-minimisation measures.

The modular structure of the EU-RMP document is flexible and allows for multiple indications, different target populations and differing NRA perspectives on risks and risk-minimisation measures. For example, if a national situation requires local epidemiological information or a specific local risk-minimisation measure, this may be captured in a country-specific annex. As emphasised by the CIOMS IX report, the decision to include an additional risk-minimisation activity and the type of activity depend on the capacity of the healthcare system of the country, i.e. what is suitable for the EU may not be applicable to an array of other regions or countries.

An alternative to the EU-RMP format may be a company-specific Core RMP format, i.e. a format highly aligned in structure and content with the EU-RMP but not containing the EU-specific additional elements.

Given the extent of information provided in the EU-RMP or any derived MAH-specific Core RMP, the IPVG recommends NRAs outside the EU accept these formats to drive toward consistent global risk management planning.

Submission of RMPs and their updates should be considered in the following situations:

-

For any new marketing authorisation application.

-

Post-authorisation, when an RMP update or a new RMP needs to be submitted at specific times, for example:

-

At the request of the local NRA.

-

With an application involving a change to an existing marketing authorisation when the data included leads to a change in the list of the safety concerns, or when a new additional pharmacovigilance activity or a new risk-minimisation measure is needed or is proposed to be removed.

-

-

Whenever significant new information is available on important risks or missing information in the benefit–risk profile of the medicinal product as well as when there are significant updates to the described pharmacovigilance activities and risk-minimisation measures

As with the PBRER, the RMP should preferably be written in a commonly understood technical language, i.e. English, to allow for consistency and to avoid translation errors. Should translations into national languages be required, a translation of summary sections could be an effective approach.

The need for the creation and maintenance of an RMP may be waived for well-established medicines, i.e. when an active ingredient of a medicine has been used for more than 10 years and its efficacy and safety have been well established [17], and those that have received an RMP waiver from an established major NRA.

10 PV System Descriptions

A PV system description is a document that describes the PV system put in place by a MAH for its medicinal product(s). It provides PV system oversight to inspectors, auditors, the MAH, the Qualified Person responsible for Pharmacovigilance (QPPV) and pharmacovigilance staff of a country or region. PV system descriptions are also a useful source of information when MAHs engage in due diligence activities and in pharmacovigilance contract management.

The first formal requirement for a PV system description in the extensive format of a Pharmacovigilance System Master File (PSMF) emerged in the EU in 2012 [18]. The EU-PSMF consists of two parts: a description of the MAH’s current PV system and the relationship between various functions and pharmacovigilance, and an annex, containing detailed information in support of the PV system. Annex examples include listings of medicinal products covered by the PV system; contractual agreements with a commercial partner, service provider and/or technical provider; ongoing and recently completed clinical trials and non-interventional studies; procedural documents; and compliance data. Per EU requirements, the PSMF must be located either at the site in the EU where the main pharmacovigilance activities of the MAH are performed or at the site in the EU where the EU-QPPV operates. To provide accurate information on the PV system(s), the PV system description and the annex should always be kept current by the MAH and be made available to EU regulators upon request. The PSMF must not be submitted as part of an EU marketing authorisation procedure.

Since the introduction of the EU-PSMF, other NRAs have also introduced PSMF requirements which follow the EU-PSMF structure and content. In part, additional country-specific sub-files/annexes/supplements are required [19].

Ideally, a PSMF text providing a description of a MAH’s global PV system should serve all NRAs worldwide. This truly global document could be complemented by a global PV system annex and by local/regional PV system descriptions and supportive local/regional annexes when required. In the absence of such a document, the IPVG recommends that existing formats for the description of a MAH’s global PV system (e.g. EU-PSMF, Core PSMF, Regional PSMF) be accepted by NRAs. When using the EU-PSMF outside the EU, applicable data protection laws may need to be observed.

11 Qualified Person for Pharmacovigilance, Local Safety Responsible, Local Contact Person

As part of the PV system, MAHs in the EU must nominate an appropriately Qualified Person responsible for Pharmacovigilance (EU-QPPV). The EU-QPPV must be at the MAH’s disposal permanently and continuously, and reside and operate in a member state of the European Economic Area (EEA). Back-up procedures must be in place in case of absence of the QPPV. The EU-QPPV’s responsibilities are to establish and maintain the MAH’s PV system, influence the performance of the quality system and the pharmacovigilance activities and to promote, maintain and improve compliance with the legal requirements. In addition, the EU-QPPV is the single pharmacovigilance contact point for the EMA and the NRAs in the EU on a 24-h/7-days basis [20].

In addition to the EU-QPPV, NRAs in the EU may also require the nomination of a local contact person at the national level. This person is expected to be knowledgeable in the specifics of the national PV system, speak the national language and facilitate communication with the NRA at the local level.

More recently, the IPVG has observed increasing requirements for QPPVs in regions outside the EU, which, at least in some areas, appear challenging for MAHs and for those in the role. Examples include Arab League and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) with their own set of GVP requirements and expectations for the QPPV. For example, as per Arab GVP, a QPPV has global PV system responsibilities, whereas a LSR bears responsibility for the local PV system.

The IPVG supports the distinction between QPPV and LSR roles and supports that the LSR role be focused on local PV system oversight. To support consistent establishment of the LSR role, the IPVG proposes that a LSR has the following profile, roles and responsibilities:

-

Oversees local pharmacovigilance processes and activities and has sufficient authority to influence the performance of the local PV system in order to comply with local applicable legislation.

-

Has adequate experience and training in locally required pharmacovigilance activities.

-

Is qualified to understand the safety profile of the MAH’s medicinal products.

-

Is not necessarily medically qualified but has access to a medically qualified person.

-

Is a resident of a country in a workable time zone (± 3 h) for the NRA, but not necessarily a resident of the country in which the NRA is located, to allow greater flexibility for MAHs which do not have a physical presence in a country and are providing medicine supplies through distributors.

-

Speaks at least one of the national languages of the country concerned, but is not necessarily a national of the country.

-

May be an employee of a third party to whom responsibilities have been delegated in writing.

-

Is available as contact person to the NRA during usual office hours of the NRA.

-

Is the contact person for local pharmacovigilance inspections.

-

Has access to the global PV system description.

-

Has access to the local PV system description should one be required.

-

Maintains regular exchange with relevant company functions such as the QPPV responsible for the global PV system, e.g. via direct contact and/or minute sharing.

Training in pharmacovigilance activities may be acquired through, e.g. online training delivered by NGO programmes or by industry funded training schemes.

Where it is possible to delegate most local PV activities to a regional or global organisation of the MAH, it may be sufficient to nominate only a local contact person for pharmacovigilance, available to the NRA during their usual office hours, and who does not need to fulfil the profile, role and responsibilities of a LSR.

In addition, a back-up person should be nominated in case of absence of the LSR/local contact person, and there should be documented evidence on who the back-up person is, the person’s location and availability.

For MAHs using a distributor model for operating internationally, the IPVG supports delegation of the QPPV/LSR roles and any required local pharmacovigilance activities to competent regional/global functions of the MAH and/or to third parties such as distributors and a service provider. Any delegation should be documented in writing.

12 Pharmacovigilance Inspections

NRAs can assess the quality and performance of a PV system through a variety of methods. Examples include the monitoring of the timely submission of ICSRs, PBRERs, RMPs and safety variations, and the review of the PV system description. In addition, inspections of the MAH’s PV system and inspections of any pharmacovigilance service provider working on behalf of a MAH are useful to check compliance with applicable regulatory requirements. Inspections are commonly conducted face to face at the MAH or service provider site, but can also be managed remotely.

It is not appropriate for the pharmaceutical industry to provide direction on NRAs’ inspection strategies and conduct. However, the IPVG would like to provide some high-level suggestions and areas for consideration aimed at NRAs which are planning pharmacovigilance inspection programmes:

-

Publication of inspection guidance may aid MAHs to prepare better for pharmacovigilance inspections.

-

Use of common grading criteria and sharing of grading examples amongst NRA inspectorates may support consistency of inspection findings.

-

Inspectorates may offer pharmacovigilance inspector trainings and shadowing of pharmacovigilance inspections to other NRAs to gain experience.

-

Risk-based inspection planning and sharing of inspection planning amongst NRA inspectorates may be advantageous to optimise inspection resource. Such planning may also avoid situations where some MAHs or service providers are rarely inspected while others are inspected multiple times in a similar time period by different inspectorates.

-

NRAs may consider providing MAHs with guidance on pharmacovigilance inspection expectations and presenting anonymised inspection findings at NRA-hosted conferences or through the publication of anonymised individual findings.

Clear inspection guidance, sharing of anonymised inspection findings as well as joint inspection training, planning and conduct will likely support raising the standards of the PV systems of MAHs and service providers and consequently contribute to improved protection of patient safety.

13 Conclusion

Robust PV systems are critical to ensure delivery of safe and effective medicines to patients worldwide. However, setting up and maintaining a PV system can be a challenge, especially in countries in the process of building their expertise or when resources are scarce. The aspiration of the IPVG is that our extensive experience can be used to support NRAs in the development of their PV systems. In this paper, we recommend a step-wise approach, using the principles of regulatory harmonisation and regulatory reliance.

References

World Health Organization. The importance of pharmacovigilance—safety monitoring of medicinal products. WHO. 2002. https://www.apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js4893e/. Accessed 24 Jan 2020.

World Health Organization. WHO Global Benchmarking Tool (GBT) for evaluation of national regulatory system of medical products, revision VI version 1. WHO. Nov 2018. https://www.who.int/medicines/areas/regulation/01_GBT_RS_RevVI.pdf. Accessed 24 Jan 2020.

The Global Fund, World Health Organization. Minimum requirements for a functional pharmacovigilance system. WHO. 2010. https://www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/safety_efficacy/PV_Minimum_Requirements_2010_2.pdf. Accessed 24 Jan 2020.

International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations. IFPMA Position Paper: Considerations for effective regulatory reliance—an Industry perspective. IFPMA. 2019. https://www.ifpma.org/resource-centre/ifpma-position-paper-on-regulatory-reliance/. Accessed 24 Jan 2020.

International Conference on Harmonisation of technical requirements for registration of pharmaceuticals for human use. E2D Post-approval safety data management: Note for guidance on definitions and standards for expedited reporting. ICH. 2003. https://www.ich.org/page/efficacy-guidelines. Accessed 24 Jan 2020.

European Medicines Agency. Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices (GVP) Module VI – Collection, management and submission of reports of suspected adverse reactions to medicinal products (Rev.2). EMA. 2017. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/guideline-good-pharmacovigilance-practices-gvp-module-vi-collection-management-submission-reports_en.pdf. Accessed 24 Jan 2020.

World Health Organization. Priming resource-limited countries for pharmacovigilance. WHO Drug Information, Vol. 31, No 4, 2017. https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/druginformation/issues/WHO_DI_31-4.pdf. Accessed 24 Jan 2020.

European Medicines Agency. Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices (GVP) Module V - Risk Management systems (Rev.2). EMA. 28 Mar 2017. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-good-pharmacovigilance-practices-module-v-risk-management-systems-rev-2_en.pdf. Accessed 24 Jan 2020.

European Medicines Agency. Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices (GVP) Module IX - Signal Management (Rev.1). EMA. 09 Oct 2017. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-good-pharmacovigilance-practices-gvp-module-ix-signal-management-rev-1_en.pdf. Accessed 24 Jan 2020.

Swissmedic. Guidance document Drug Safety Signals HMV4. Swissmedic. 01.01.2020. https://www.swissmedic.ch/swissmedic/en/home/humanarzneimittel/market-surveillance/risk-management--psurs--pv-planning-.html. Accessed 24 Jan 2020.

Council for International Organisations of Medical Sciences. Practical aspects of signal detection in pharmacovigilance. Report of CIOMS Working Group VIII. CIOMS. 2010.

European Medicines Agency. Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices (GVP) Annex I - Definitions (Rev.4). EMA. 09 Oct 2017. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-good-pharmacovigilance-practices-annex-i-definitions-rev-4_en.pdf. Accessed 24 Jan 2020.

European Medicines Agency. Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices (GVP) Module XV – Safety communication (Rev.1). EMA. 09 Oct 2017. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-good-pharmacovigilance-practices-module-xv-safety-communication-rev-1_en.pdf. Accessed 24 Jan 2020.

International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. Periodic benefit-risk evaluation report (PBRER) E2C(R2). ICH. 2012. https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/E2C_R2_Guideline.pdf. Accessed 24 Jan 2020.

Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences. Guidelines for preparing core clinical-safety information on drugs second edition—report of CIOMS working groups III and V. CIOMS. 1999.

European Medicines Agency. Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices (GVP) Module VII—periodic safety update report (Rev.1). EMA. 2013. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-good-pharmacovigilance-practices-gvp-module-vii-periodic-safety-update-report_en.pdf. Accessed 24 Jan 2020.

The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 November 2001 on the Community code relating to medicinal products for human use. https://www.eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2001:311:0067:0128:en:PDF. Accessed 24 Jan 2020.

European Medicines Agency. Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices (GVP) Module II—Pharmacovigilance system master file (Rev.2). EMA. 2017. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-good-pharmacovigilance-practices-module-ii-pharmacovigilance-system-master-file-rev-2_en.pdf. Accessed 24 Jan 2020.

The League of Arab States. Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices (GVP) for Arab countries. Version 2. 2014. https://www.jfda.jo/EchoBusV3.0/SystemAssets/PDF/AR/PharmVigilance/TheGoodPharmacovigilancePracticev2.pdf. Accessed 24 Jan 2020.

European Medicines Agency. GVP module I—pharmacovigilance systems and their quality systems: EMA. 2012. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-good-pharmacovigilance-practices-module-i-pharmacovigilance-systems-their-quality-systems_en.pdf. Accessed 24 Jan 2020.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable contribution of Mr. Sean Burke (MSD), consisting of critical review and advice on key elements of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Tanja Peters: funding for this research included working hours dedicated to this research remunerated by Boehringer Ingelheim as part of salary. No additional sources of funding were stated by the authors as being used to assist in the preparation of this study.

Conflict of interest

Tanja Peters was employed at Boehringer Ingelheim at the time this research was completed. As of April 1, 2020, Tanja Peters is an employee of Merck Healthcare KGaA and owns stocks of Merck KGaA. Tanja Peters also conducts ancillary work with the Forum Institute for Professional Training in Heidelberg, Germany. Nigel Soanes is employed by AstraZeneca and has reported no additional conflicts of interest. Maya Abbas is employed by Johnson & Johnson Middle East and declares that she has no conflict of interest. Jabeen Ahmad was previously employed by AbbVie and Innovate PV during the writing of the manuscript. Jabeen is now employed by Roche and has reported no conflicts of interest. Jean-Christophe Delumeau is employed by Bayer, serving pro bono the International Society of Pharmacovigilance as a board and executive committee member. He has not reported additional conflicts of interest. Esteban Herrero-Martinez is employed by AbbVie and has reported no additional conflicts of interest. Mélanie Paramananda is employed by Pierre Fabre and has reported no additional conflicts of interest. Johanna Piper is employed by Roche Products Ltd and has reported no additional conflicts of interest. Fairouz Smail-Aoudia is employed by Pierre Fabre and has reported no additional conflicts of interest. Willemijn van der Spuij is employed by Bristol Myers Squibb and has reported no additional conflicts of interest. Tina Veizovic is employed by Takeda and has reported no additional conflicts of interest. Gillian Winstanley is employed by Amgen Canada Inc. and has reported no additional conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

Not applicable, as this article does not refer to data relative to individuals.

Consent to participate

Not applicable, as this article does not refer to data relative to individuals.

Consent for publication

Not applicable, as this article does not refer to data relative to individuals.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study. The materials referred to in this article consist of guidelines and legislation publicly available on the websites of the respective institutions.

Code availability

Not applicable, as no computer system was used for data compilation or analysis.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and writing of the review. All Authors read and approved the manuscript.

Additional information

This paper has been reviewed by IFPMA.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peters, T., Soanes, N., Abbas, M. et al. Effective Pharmacovigilance System Development: EFPIA-IPVG Consensus Recommendations. Drug Saf 44, 17–28 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-020-01008-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-020-01008-0