Abstract

Accumulating neurological disability has a substantial impact on the lives of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS). As well as the established Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS), several other outcome measures are now available for assessing disability progression in MS. This review extends the findings of a previous analysis of relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) trials published up to 2012, to determine whether there has been a shift in outcome measures used to assess disability in phase III clinical trials in RRMS and progressive MS. Forty relevant trials were identified (RRMS, n = 16; progressive MS, n = 18; other/mixed phenotypes, n = 6). Sustained EDSS worsening, particularly over 3 months, was included as an endpoint in almost all identified trials. Other disability-related endpoints included the Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite z-score and scores for the physical component summary of the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale and Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form (36-item) Health Survey. Tests assessing manual dexterity, ambulation, vision and cognition were also employed, and in some trials, composite endpoints were used. However, there was no obvious trend in choice of disability outcome measures over time. Sustained EDSS worsening over short time periods continues to be the most widely used measure of disability progression in pivotal MS trials, despite its well-recognised limitations. A new tool set is needed for use in MS clinical trials that detects the benefit of potential treatments that slow (or reverse) progressive disability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Despite its limitations, a short-term sustained increase in the EDSS score continues to be the most widely used disability outcome measure in clinical trials in MS. Other outcome measures have been used, but mainly as secondary endpoints. |

There is a need for outcome measures that more accurately reflect irreversible disability progression in MS. This includes not only mobility but also other key symptom domains such as manual dexterity, cognition and visual function. |

Ideally, measures used to assess disability progression in MS should reflect outcomes that are important to the patient. They should also be designed to allow their incorporation into busy, everyday clinical practice as well as clinical trials. |

1 Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease characterised by clinical neurological relapses and progressive neurological disability [1]. Relapses are thought to reflect acute focal inflammation, while progressive disability likely represents chronic, diffuse neurodegeneration [2]. According to the classical view of the natural history of MS, focal inflammation is the precursor of neurodegeneration, with successive relapses leading to accumulation of disability [2]. However, the contemporary view of MS is that there is a dissociation between relapses and long-term disability [3].

Not surprisingly, accumulating neurological disability has a substantial impact on the lives of the relatively young population of patients affected by MS. Studies have shown that increasing levels of disability have a negative effect on the quality of life (QoL) of both patients and caregivers [4,5,6]. Furthermore, overall costs associated with MS increase as disability accumulates [7], with direct medical costs contributing more in the earlier stages of disease and indirect costs (e.g. productivity loss) predominating in the later stages [8]. The main goal of managing MS is therefore to reduce, or preferably prevent, long-term disability progression [9]. Hence, clinicians involved in the management of MS, whether from a clinical or research perspective, need access to specific, reliable, valid and sensitive tools that measure patient disability. This is challenging in view of the highly variable clinical expression and course of the disease [10].

The Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) [11] was introduced in the early 1980s and is the most widely used tool for assessing MS disability in clinical trials [10]. In clinical practice, it is mainly used in specialist MS centres, while non-specialists may use the EDSS as a basis for their assessments. Measured on a scale of 0 (normal neurological function) to 10 (death due to MS), the lower range (up to 4.0) measures impairment in eight functional systems, the mid range (4.0–7.0) focuses on ambulatory function, and the top range (7.0–9.5) largely assesses the ability to carry out activities of daily living [10]. Its main advantage is undoubtedly its widespread use, which fosters familiarity and acceptance among neurologists and permits a degree of comparison between different studies [10, 12]. However, its limitations are well recognised and include high levels of variability, non-linearity (which complicates statistical analysis), limited sensitivity and insufficient assessment of domains such as upper limb function and cognition [10, 12, 13]. A training platform called Neurostatus, which incorporates a standardised neurological examination form, has been developed to reduce variability and improve both inter- and intra-rater reliability of EDSS assessments [14].

Other measures of disability include the timed 25-foot walk (T25FW), which assesses ambulatory function [15], and the 9-hole peg test (9HPT), which measures upper body function and manual dexterity [16]. Both tests, along with the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task (PASAT), which measures an aspect of cognitive function, are components of the Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite (MSFC), which was introduced in the late 1990s to address some of the limitations of the EDSS [17]. To calculate the overall score, results from the three tests are transformed into z-scores by standardising to a reference population, then averaged to create the composite MSFC z-score [12]. The validity and reliability of the MSFC have been demonstrated [18] and results have been shown to correlate with EDSS scores, changes in magnetic resonance imaging measures, and patients’ QoL [18, 19]. Nevertheless, it does have some limitations, including practice effects with the PASAT (improved performance with repeated testing), issues with z-scores (lack of intuitiveness; variations in reference populations) and lack of a consensus on the definition of clinically important change [12, 18]. Furthermore, despite acceptance of its component tests, limited clinical interpretability [12] and a lack of familiarity remain major concerns preventing the broader use of the overall MSFC score.

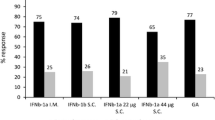

In 2014, Lavery et al. conducted a review of the outcome measures used to assess disability progression in relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) trials published up to 2012 [20]. Within the 19 trials included in their analysis, the most commonly used measure was sustained worsening of EDSS over a 3-month period. This endpoint was first reported when data from a trial of glatiramer acetate were published in 1995 [21]. A more rigorous measure of disability progression, based on worsening of EDSS over 6 months, was first reported 13 years later in 2008, when data from the REGARD trial (subcutaneous interferon β-1a vs. glatiramer acetate) were published. The first use of MSFC was reported 2 years earlier, when the results of the CHAMPIONS [22], AFFIRM [23] and SENTINEL [24] studies were published.

The aim of this current review was to extend the findings of Lavery et al. [20] to determine whether there has been a shift in the outcome measures used to assess disability in published and ongoing phase III clinical trials, not only in RRMS but also in progressive forms of MS.

2 Methods

Published phase III trials in RRMS and progressive MS were identified via a PubMed search (conducted on 31 May 2017) using appropriate terminology (Online Resource 1a). The results were hand-searched to exclude any non-relevant publications. The bibliographies of relevant review articles were also hand-searched for publications not captured using PubMed. RRMS trials published before 2012 were excluded as this time period was covered in the review by Lavery et al. [20]. Searches for progressive MS trials were limited to the last 20 years.

Ongoing or unpublished phase III trials were identified via ClinicalTrials.gov (search conducted 13 June 2017) using appropriate search terminology (Online Resource 1b). The results were hand-searched to exclude non-relevant trials (e.g. those that evaluated pain, fatigue or immunogenicity). Extension and non-comparative trials, as well as those denoted as ‘withdrawn’ or of ‘unknown status’, were excluded. Trials denoted as ‘completed’ and with linked publications were cross-checked against the list of published trials found using PubMed, and added if necessary.

Searches were not limited to products licensed to treat MS; drugs for which development is ongoing or was subsequently terminated were also included.

3 Results

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

3.1 Phase III Relapsing or Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis Trials

Overall, 16 phase III trials were identified in relapsing MS or RRMS (12 published from 2012 onwards and four unpublished) (Table 1). Three additional articles published before 2012, but not included in the review by Lavery et al., were also identified [37,38,39]. Two of these trials evaluated disability progression according to sustained (3-month) worsening of EDSS (the other did not include a disability-related outcome), therefore the conclusions from the review by Lavery et al. are not changed by inclusion of the outcomes reported in these additional publications.

The 16 trials identified were initiated between 2005 and 2014. As expected, the primary endpoint in most trials was the annualised relapse rate (ARR). In two trials (CARE MS-I [27] and CARE MS-2 [28]), the primary endpoint was a composite of relapse rate and sustained disability progression; in one unpublished trial, the primary endpoint was sustained worsening of EDSS over 3 months.

Secondary endpoints used to assess disability were sustained worsening of EDSS over 3, 6 and/or 9 months, changes in the EDSS score, changes in the MSFC z-score, freedom from disease activity or no evidence of disease activity, the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29) physical component score, the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form (36-item) Health Survey (SF-36) physical component summary score, a visual function test and a test to assess cognition (Fig. 1).

Disability outcomes measures used in phase III relapsing multiple sclerosis or RRMS trials (n = 16). Includes unpublished trials and trials published from 2012 onwards (with the exception of the DEFINE and CONFIRM trials, which are included in the review by Lavery et al. [20]). EDSS Expanded Disability Status Scale, FDA freedom from disease activity, MSFC Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite, MSIS Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale, NEDA no evidence of disease activity, SF-36 Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form (36-item) Health Survey, RRMS relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis

The latter two were tertiary endpoints in a single trial [35]. Two trials had no specified disability outcome measures [32, 34] and one trial evaluated sustained improvement in EDSS (over 3 months) as a tertiary endpoint [35].

There was no obvious trend in the choice of disability outcome measures over time, based on the year in which trials were initiated (Fig. 2).

Disability outcome measures used over time in phase III relapsing multiple sclerosis or RRMS trials (n = 16). Includes unpublished trials and trials published from 2012 onwards (with the exception of the DEFINE and CONFIRM trials, which are included in the review by Lavery et al. [20]); ongoing trials were sourced from ClinicalTrials.gov; dates refer to study initiation. EDSS Expanded Disability Status Scale, FDA freedom from disease activity, MSFC Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite, MSIS Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale, NEDA no evidence of disease activity, SF-36 Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form (36-item) Health Survey, RRMS relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. There was one trial published in 2014, which did not include any disability outcome measures

3.2 Phase III Progressive Multiple Sclerosis Trials

Overall, 15 articles (published in the last 20 years) reporting phase III trials in progressive MS were identified; three ongoing trials were also identified (Table 2). All of these trials used a disability outcome measure as the primary endpoint and the range of disability endpoints was more diverse than those included in RRMS trials (Fig. 3).

Disability outcome measures used in phase III progressive MS trials (n = 18): a EDSS-related measures; b other outcome measures. Includes unpublished trials and trials published from 1997 onwards; note that in some trials, endpoints relating to the same measure were included as both primary and secondary endpoints (e.g. time to 3-month worsening of EDSS and the proportion of patients with 3-month worsening of EDSS). AUC area under the curve, CGI-I Clinical Global Impression of Improvement, EDSS Expanded Disability Status Scale, MSFC Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite, MS multiple sclerosis, PGI-I Patient Global Impression of Improvement, RFSS Regional Functional System Score, SF-36 Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form (36-item) Health Survey, SNRS Scripps Neurologic Rating Scale

The most commonly used primary endpoint was sustained EDSS worsening over 3 or 6 months. These were first used in trials published in 1998 [40] and 2004 [45], respectively, and, most recently, in trials published in 2017 [55] and 2011 [53], respectively (as well as in one ongoing trial [NCT01665144]). In two other trials, one published in 2004 [47] and the other published in 2007 [51], 3-month EDSS worsening was included as a co-primary endpoint. More recent trials (one published in 2016 [54] and two ongoing [NCT02220933 and NCT02936037]) had a primary endpoint that defined progressors as those patients meeting at least one of two or three disability endpoints (deterioration in EDSS, T25FW or 9HPT results).

Among the range of secondary endpoints used, sustained EDSS worsening over 3 or 6 months was the most commonly used (Fig. 3). Two novel EDSS endpoints (area under the EDSS–time curve [46] and slope of the EDSS progression curve [42]) were used, albeit in only one trial each. Additional disability outcomes assessed ambulation [45, 54, 55, 57,58,59], upper body function [45, 46, 50, 54, 59], cognition [48, 50, 57] and visual function [46, 50]. In one of the ongoing trials, ambulation is being measured remotely [57].

Based on the year in which trials were published, there was no obvious trend in the choice of disability outcome measures over time (Fig. 4).

Disability outcome measures used over time in phase III progressive MS trials published since 2007 (n = 18): a EDSS-related measures; b other outcome measures. Published trials only (trials could not be assessed according to start date, as this was not available for all published trials). EDSS Expanded Disability Status Scale, MS multiple sclerosis, MSFC Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite, RFSS Regional Functional Scoring Scale, SF–36 Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form (36-item) Health Survey, SNRS Scripps Neurologic Rating Scale

3.3 Other Phase III Trials

Six additional trials were identified (two published [60, 61] and four ongoing); five of these trials included patients with relapsing or progressive MS, and one included patients at high risk of progression during the initial MS phase (MITOX-REBIF) (Table 3). In the published trials, the primary and secondary endpoints focused on sustained EDSS worsening over 3 months. In the ongoing RRMS/secondary progressive MS trials, the primary endpoint is ARR, and secondary disability endpoints are sustained (3- and 6-month) EDSS worsening and sustained (6-month) EDSS improvement. In the MITOX-REBIF trial, the primary endpoint is a composite measure that accounts for relapses and EDSS progression, and the secondary endpoints are the EDSS score and rate of progression to clinically definite MS (in those with a single clinical event before initiation of treatment).

4 Discussion

The current evaluation highlights the wide range of endpoints that have been used to evaluate disability in phase III clinical trials in MS, particularly in progressive forms of the disease. As one might expect, disability measures were assessed as both primary and secondary endpoints in progressive MS trials, whereas the primary endpoint in most RRMS trials was based on the relapse rate. While entirely rational, this in itself presents a challenge in assessing treatment differences in disability progression in RRMS as trials are powered to detect differences in primary, but not secondary, endpoints. Trials including relapsing and progressive MS phenotypes have either relapses or disability progression as the primary endpoint, although one ongoing study has a composite endpoint (absence of relapses and an increase in EDSS ≤ 1) [NCT02937285].

Based on the current analysis, it is difficult to discern any evolution over time in the primary or secondary disability outcome measures used in these trials. As found in the previous review by Lavery et al. [20], sustained EDSS worsening, particularly over 3 months, is widely used and was included as an endpoint in almost all of the trials identified, including those that are ongoing. This is interesting as it has been shown that short-term changes in EDSS do not correctly identify patients with truly irreversible disability progression. For example, in a trial of 929 patients with RRMS or clinically isolated syndrome, sustained progression was maintained (over a mean follow-up of 45 months) in fewer than 50% of those meeting the initial criteria for EDSS progression (mainly over 6 months) [62]. In another trial, which included data from over 16,000 patients, approximately 70% of patients with EDSS worsening over 3 or 6 months had sustained disability over 5 years; this increased to 80 and 89% when the criteria were changed to EDSS worsening over 12 and 24 months, respectively [63]. In this context, it is interesting that in the CONCERTO trial [64], one of the endpoints was the EDSS progression over 9 months, the longest time period reported in any of the trials included in the current evaluation. Although the issue of using short-term EDSS changes is particularly pertinent to relapsing MS (in view of the potential confounding effects of transient, relapse-related neurological impairment), it is also recognised that the EDSS has limited ability to detect clinically relevant disability progression in progressive MS [65]. In a recent analysis of data from the placebo arm of the PROMiSe trial, which was conducted in patients with primary progressive MS [49], sustained (3-month) worsening of the EDSS was less sensitive to disability progression than sustained (3-month) changes in the T25FW (≥ 20% increase) or composite measures (EDSS or T25FW; EDSS or 9HPT [≥ 20% increase]; EDSS, T25FW or 9HPT). The authors concluded that T25FW or composite measures should be considered as the primary endpoint for future studies of new disease-modifying therapies [66].

Despite its limitations, the EDSS is the only disability outcome measure currently advocated by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for trials in MS [67]. More specifically, the EMA advises that the mean change in EDSS score from baseline is not appropriate and that sustained worsening of a relevant magnitude over a prespecified timeframe should be used. This undoubtedly explains, at least in part, the persistent use of sustained EDSS worsening over 3 or 6 months in the trials identified as part of the current evaluation. However, the EMA does acknowledge that there is a need for alternative measures (see below for information on the Multiple Sclerosis Outcome Assessments Consortium [68, 69]), and research in this area has been active for many years. The MSFC was first introduced almost 20 years ago to address some of the limitations of the EDSS [17], and a recent meta-analysis has shown it to be more sensitive than the EDSS for detecting progression of MS [70]. The MSFC was included in over half (9/16) of the phase III RRMS trials identified in the current evaluation, although it was a primary endpoint in only one [43]. Perhaps surprisingly, the MSFC was used in only 5/20 phase III trials (25%) in progressive MS. Two factors that may have limited the use of the MSFC are lack of clarity (until relatively recently, at least [15, 16]) on the magnitude of clinically significant changes for the three component tests [12] and patients’ dislike of the PASAT (used to assess cognition) [15, 16]. The major issue is probably the lack of acceptance by regulatory agencies, which is most likely driven by the poor clinical interpretability of the overall score [12]. Other approaches taken to improve on disability assessment include development of the EDSS-Plus, which includes the EDSS and the 9HPT and T25FW [71], and use of a roving versus fixed reference value [72].

Among the trials identified in the current evaluation, some included secondary outcomes to assess manual dexterity and cognition, aspects of disability progression that are not evaluated by the EDSS. Some also included separate measures of ambulation, one of the most valued functions for patients with MS [15]. Although the data obtained for these endpoints are informative, as discussed above, trials are designed and specifically powered to detect statistical treatment differences in primary endpoints, but not necessarily in secondary endpoints.

Other pertinent observations include the use, in some trials, of composite endpoints to assess disability progression. These include a single composite score of five component measures [44], as well as endpoints for which patients only had to satisfy one of two or more criteria to be classified as progressors (e.g. increase in EDSS score or ≥ 20% worsening on the 9HPT) [46, 54]. Interestingly, when testing the EDSS-Plus (see above), it was observed that defining progression on at least one of three components (EDSS, T25FW or 9HPT) identified 60% of patients as progressors, compared with 25, 42 and 34%, respectively, when using the individual tests alone [71].

The inclusion of endpoints to evaluate disability improvement is also pivotal as it marks the start of a shift in the goals for treating MS, from limiting disability progression to reversing it, using not only agents aimed at halting disease activity but also interventions intended to repair and remyelinate [73]. However, use of the EDSS to assess disability improvement is subject to the same limitations as its use to assess disability progression, and discussions regarding more appropriate endpoints to measure improvement have already started [74]. Another advance in the assessment of disability in MS is the possibility of measuring physical activity and ambulation remotely [75, 76]. The feasibility of remote evaluation of cognitive and patient-reported outcomes in MS has also been assessed [77,78,79].

One of the potential limitations of the current evaluation was the use of PubMed to identify phase III MS trials, thus relying on inclusion of the term ‘phase 3’ (or ‘phase III’) in the abstract or Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms; however, the bibliographies of review articles on the treatment of MS were also screened to address this. Another limitation, in the context of assessing the evolution of disability outcome measures over time, is that it was not possible to ascertain the start date for all of the trials in progressive MS. The evaluation was therefore conducted according to the trial publication date, which may not truly reflect the chronology of the trials. Nevertheless, it gives a general overview of disability-related outcomes assessed in phase III trials, adding to that provided by Lavery et al. in trials of RRMS [20], and providing useful information on progressive MS trials conducted over the last 20 years.

The need for improved disability outcome measures is recognised by the wider MS community. The international MS Outcome Assessments Consortium was set up to develop a tool set for use in MS clinical trials that can detect the benefit of potential treatments that slow or reverse progressive disability, and is recognised as a primary outcome measure by regulatory authorities [68, 69, 80]. The consortium, which includes representatives from academic institutions, pharmaceutical companies, the EMA, US FDA and National Institutes for Health, recently published four papers reviewing the evidence for the validity of four outcome measures: the T25FW, the 9HPT, the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) and the Low-Contrast Visual Acuity Test (LCVA), suggesting that these scales will be included in the final tool set [15, 16, 81, 82]. These scales assess ambulation, manual dexterity, cognition and vision, respectively, as impairments to these functions represent core symptoms in MS [81]. The SDMT was selected to measure cognition rather than the PASAT (which is part of the MSFC) as it has shown superior reliability and sensitivity and greater patient acceptability [82]. With regard to visual function, which is not captured by the MSFC, LCVA was selected as it captures visual loss not identified using high-contrast visual acuity tests [81]. The four manuscripts also include information on the magnitude of clinically meaningful changes (T25FW, ≥ 20%; 9HPT, ≥ 20%; SDMT, ≥ 4 points or ≥ 10%; LCVA, ≥ 7%) based on published data [15, 16, 81, 82].

5 Conclusions

The current evaluation indicates that despite its serious and well-recognised limitations, sustained EDSS worsening continues to be widely used as an endpoint in phase III trials in MS. As such, disability progression has tended to focus on the assessment of mobility. Although mobility is important, there are other domains of MS that are relevant to the detection of progression. Additional outcome measures that assess these domains have been available for many years, but there is now renewed focus on their psychometric and regulatory validation, which should facilitate their more extensive use in the future. Combination endpoints (whereby efficacy is measured according to whether a patient meets one or more of multiple prespecified outcomes) have been used in a small number of recent trials and may improve sensitivity in terms of detecting a change in disability; however, the effect size expected in future trials is unknown and the most appropriate combination of outcome measures may be difficult to predict in a specific population treated with specific therapies with differing mechanisms of action [83]. Ideally, a multifaceted approach should be adopted that explores aspects of the disease that are directly relevant to patients, and patient involvement should be considered when developing new outcomes to assess disability progression in MS. Another challenge is to ensure that outcome measures developed in the context of clinical trial conduct are suitable for use in busy, everyday clinical practice.

References

Confavreux C, Vukusic S, Moreau T, et al. Relapses and progression of disability in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1430–8.

Confavreux C, Vukusic S. Accumulation of irreversible disability in multiple sclerosis: from epidemiology to treatment. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2006;108:327–32.

Tremlett H, Zhao Y, Rieckmann P, et al. New perspectives in the natural history of multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2010;74:2004–15.

Ertekin O, Ozakbas S, Idiman E. Caregiver burden, quality of life and walking ability in different disability levels of multiple sclerosis. NeuroRehabilitation. 2014;34:313–21.

Green G, Todd J. ‘Restricting choices and limiting independence’: social and economic impact of multiple sclerosis upon households by level of disability. Chronic Illn. 2008;4:160–72.

Naci H, Fleurence R, Birt J, et al. The impact of increasing neurological disability of multiple sclerosis on health utilities: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Econ. 2010;13:78–89.

Kobelt G, Thompson A, Berg J, et al. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe. Mult Scler. 2017;23:1123–36.

Naci H, Fleurence R, Birt J, et al. Economic burden of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28:363–79.

Goodin DS, Reder AT, Bermel RA, et al. Relapses in multiple sclerosis: relationship to disability. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016;6:10–20.

van Munster CE, Uitdehaag BM. Outcome measures in clinical trials for multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs. 2017;31:217–36.

Kurtzke JF. Historical and clinical perspectives of the expanded disability status scale. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;31:1–9.

Goldman MD, Motl RW, Rudick RA. Possible clinical outcome measures for clinical trials in patients with multiple sclerosis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2010;3:229–39.

Tur C, Moccia M, Barkhof F, et al. Assessing treatment outcomes in multiple sclerosis trials and in the clinical setting. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14:75–93.

Neurostatus.net. 2016. https://www.neurostatus.net/index.php. Accessed Apr 2018.

Motl RW, Cohen JA, Benedict R, et al. Validity of the timed 25-foot walk as an ambulatory performance outcome measure for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2017;23:704–10.

Feys P, Lamers I, Francis G, et al. The Nine-Hole Peg Test as a manual dexterity performance measure for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2017;23:711–20.

Cutter GR, Baier ML, Rudick RA, et al. Development of a multiple sclerosis functional composite as a clinical trial outcome measure. Brain. 1999;122:871–82.

Polman CH, Rudick RA. The multiple sclerosis functional composite: a clinically meaningful measure of disability. Neurology. 2010;74(Suppl 3):S8–15.

Miller DM, Rudick RA, Cutter G, et al. Clinical significance of the multiple sclerosis functional composite: relationship to patient-reported quality of life. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:1319–24.

Lavery AM, Verhey LH, Waldman AT. Outcome measures in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: capturing disability and disease progression in clinical trials. Mult Scler Int. 2014;2014:262350.

Johnson KP, Brooks BR, Cohen JA, et al. Copolymer 1 reduces relapse rate and improves disability in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: results of a phase III multicenter, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. The Copolymer 1 Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Neurology. 1995;45:1268–76.

Kinkel RP, Kollman C, O’Connor P, et al. IM interferon beta-1a delays definite multiple sclerosis 5 years after a first demyelinating event. Neurology. 2006;66:678–84.

Polman CH, O’Connor PW, Havrdova E, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:899–910.

Rudick RA, Stuart WH, Calabresi PA, et al. Natalizumab plus interferon beta-1a for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:911–23.

Lublin FD, Cofield SS, Cutter GR, et al. Randomized study combining interferon and glatiramer acetate in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2013;73:327–40.

Calabresi PA, Radue EW, Goodin D, et al. Safety and efficacy of fingolimod in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (FREEDOMS II): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:545–56.

Cohen JA, Coles AJ, Arnold DL, et al. Alemtuzumab versus interferon beta 1a as first-line treatment for patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2012;380:1819–28.

Coles AJ, Twyman CL, Arnold DL, et al. Alemtuzumab for patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis after disease-modifying therapy: a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2012;380:1829–39.

Comi G, Jeffery D, Kappos L, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of oral laquinimod for multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1000–9.

Vollmer TL, Sorensen PS, Selmaj K, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled phase III trial of oral laquinimod for multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2014;261:773–83.

Confavreux C, O’Connor P, Comi G, et al. Oral teriflunomide for patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (TOWER): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:247–56.

Vermersch P, Czlonkowska A, Grimaldi LM, et al. Teriflunomide versus subcutaneous interferon beta-1a in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: a randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Mult Scler. 2014;20:705–16.

Calabresi PA, Kieseier BC, Arnold DL, et al. Pegylated interferon beta-1a for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (ADVANCE): a randomised, phase 3, double-blind study. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:657–65.

Khan O, Rieckmann P, Boyko A, et al. Three times weekly glatiramer acetate in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2013;73:705–13.

Kappos L, Wiendl H, Selmaj K, et al. Daclizumab HYP versus interferon beta-1a in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1418–28.

Cohen J, Belova A, Selmaj K, et al. Equivalence of generic glatiramer acetate in multiple sclerosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:1433–41.

Comi G, Cohen JA, Arnold DL, et al. Phase III dose-comparison study of glatiramer acetate for multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:75–82.

Giovannoni G, Comi G, Cook S, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of oral cladribine for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:416–26.

O’Connor P, Filippi M, Arnason B, et al. 250 μg or 500 μg interferon beta-1b versus 20 mg glatiramer acetate in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a prospective, randomised, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:889–97.

Kappos L, European Study Group on Interferon β-1b in Secondary Progressive MS. Placebo-controlled multicentre randomised trial of interferon beta-1b in treatment of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1998;352:1491–7.

Rice GP, Filippi M, Comi G, Cladribine MRI Study Group. Cladribine and progressive MS: clinical and MRI outcomes of a multicenter controlled trial. Neurology. 2000;54:1145–55.

SPECTRIMS Study Group. Randomized controlled trial of interferon-beta-1a in secondary progressive MS: clinical results. Neurology. 2001;56:1496–504.

Cohen JA, Cutter GR, Fischer JS, et al. Benefit of interferon beta-1a on MSFC progression in secondary progressive MS. Neurology. 2002;59:679–87.

Hartung HP, Gonsette R, Konig N, et al. Mitoxantrone in progressive multiple sclerosis: a placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomised, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2002;360:2018–25.

Andersen O, Elovaara I, Farkkila M, et al. Multicentre, randomised, double blind, placebo controlled, phase III study of weekly, low dose, subcutaneous interferon beta-1a in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:706–10.

Hommes OR, Maas-Enriquez M. ESIMS—an ongoing clinical trial in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2000;6(Suppl 2):S27–32.

Hommes OR, Sorensen PS, Fazekas F, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1149–56.

Panitch H, Miller A, Paty D, et al. Interferon beta-1b in secondary progressive MS: results from a 3-year controlled study. Neurology. 2004;63:1788–95.

Wolinsky JS, Narayana PA, O’Connor P, et al. Glatiramer acetate in primary progressive multiple sclerosis: results of a multinational, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:14–24.

Poehlau D, Federlein J, Postert T, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) treatment for patients with primary or secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: outline of a double-blind randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Mult Scler. 1997;3:149–52.

Pöhlau D, Przuntek H, Sailer M, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin in primary and secondary chronic progressive multiple sclerosis: a randomized placebo controlled multicentre study. Mult Scler. 2007;13:1107–17.

Hawker K, O’Connor P, Freedman MS, et al. Rituximab in patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis: results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:460–71.

Freedman MS, Bar-Or A, Oger J, et al. A phase III study evaluating the efficacy and safety of MBP8298 in secondary progressive MS. Neurology. 2011;77:1551–60.

Lublin F, Miller DH, Freedman MS, et al. Oral fingolimod in primary progressive multiple sclerosis (INFORMS): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1075–84.

Montalban X, Hauser SL, Kappos L, et al. Ocrelizumab versus placebo in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:209–20.

Brochet B, Deloire MS, Perez P, et al. Double-blind controlled randomized trial of cyclophosphamide versus methylprednisolone in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0168834.

ClinicalTrials.gov. Effect of MD1003 in progressive multiple sclerosis (SPI2). 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02936037?term=02936037&rank=1. Accessed Aug 2017.

ClinicalTrials.gov. Exploring the efficacy and safety of siponimod in patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (EXPAND). 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01665144?term=01665144&rank=1. Accessed Aug 2017.

ClinicalTrials.gov. Effect of MD1003 in spinal progressive multiple sclerosis (MS-SPI). 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02220933?term=02220933&rank=1. Accessed Aug 2017.

Noseworthy JH, O’Brien P, Erickson BJ, et al. The Mayo Clinic-Canadian Cooperative trial of sulfasalazine in active multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1998;51:1342–52.

Noseworthy JH, Wolinsky JS, Lublin FD, et al., and the North American Linomide Investigators. Linomide in relapsing and secondary progressive MS part I: trial design and clinical results. Neurology. 2000;54:1726–33.

Healy BC, Engler D, Glanz B, et al. Assessment of definitions of sustained disease progression in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Int. 2013;2013:189624.

Kalincik T, Cutter G, Spelman T, et al. Defining reliable disability outcomes in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2015;138:3287–98.

ClinicalTrials.gov. The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of laquinimod in subjects with relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) (CONCERTO). 2017. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01707992?term=01707992&rank=1. Accessed Jul 2017.

Cadavid D, Tang Y, O’Neill G. Responsiveness of the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) to disease progression and therapeutic intervention in progressive forms of multiple sclerosis. Rev Neurol. 2010;51:321–9 (in Spanish).

Koch MW, Cutter GR, Giovannoni G, et al. Comparative utility of disability progression measures in PPMS: analysis of the PROMiSe data set. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2017;4:e358.

European Medicines Agency. Guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. 2015. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2015/03/WC500185161.pdf. Accessed Jul 2017.

LaRocca NG, Hudson LD, Rudick R, et al. The MSOAC approach to developing performance outcomes to measure and monitor multiple sclerosis disability. Mult Scler. 2017:1352458517723718.

Rudick RA, Larocca N, Hudson LD. Multiple Sclerosis Outcome Assessments Consortium: genesis and initial project plan. Mult Scler. 2014;20:12–7.

Bin Sawad A, Seoane-Vazquez E, Rodriguez-Monguio R, et al. Evaluation of the Expanded Disability Status Scale and the multiple sclerosis functional composite as clinical endpoints in multiple sclerosis clinical trials: quantitative meta-analyses. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:1969–74.

Cadavid D, Cohen JA, Freedman MS, et al. The EDSS-Plus, an improved endpoint for disability progression in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2017;23:94–105.

Kappos L, Butzkueven H, Wiendl H, et al. Greater sensitivity to multiple sclerosis disability worsening and progression events using a roving versus a fixed reference value in a prospective cohort study. Mult Scler. 2017:1352458517709619.

Plemel JR, Liu WQ, Yong VW. Remyelination therapies: a new direction and challenge in multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16(9):617–34.

Sormani MP, Pardini M. Assessing repair in multiple sclerosis: outcomes for phase II clinical trials. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(4):924–33.

Block VA, Pitsch E, Tahir P, et al. Remote physical activity monitoring in neurological disease: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0154335.

Block VJ, Lizee A, Crabtree-Hartman E, et al. Continuous daily assessment of multiple sclerosis disability using remote step count monitoring. J Neurol. 2017;264:316–26.

Engelhard MM, Patek SD, Sheridan K, et al. Remotely engaged: Lessons from remote monitoring in multiple sclerosis. Int J Med Inform. 2017;100:26–31.

George MF, Holingue CB, Briggs FB, et al. Feasibility study for remote assessment of cognitive function in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neuromed. 2016;1:10–8.

Settle JR, Robinson SA, Kane R, et al. Remote cognitive assessments for patients with multiple sclerosis: a feasibility study. Mult Scler. 2015;21:1072–9.

National Multiple Sclerosis Society. National MS Society-supported collaborators publish reviews of tools used to measure MS progression. 2017. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/About-the-Society/News/National-MS-Society-Supported-Collaborators-Publis. Accessed Jun 2017.

Balcer LJ, Raynowska J, Nolan R, et al. Validity of low-contrast letter acuity as a visual performance outcome measure for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2017;23:734–47.

Benedict RH, DeLuca J, Phillips G, et al. Validity of the Symbol Digit Modalities Test as a cognition performance outcome measure for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2017;23:721–33.

Ontaneda D, Cohen JA, Amato MP. Clinical outcome measures for progressive MS trials. Mult Scler. 2017;23:1627–35.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Nicky French, PhD, of Anthemis Consulting Ltd provided editorial support, funded by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Frazer, PA, USA. Teva provided a single medical-accuracy review of the final draft. The author was not compensated and retained full editorial control over the content of the paper. Open access was funded by VU University Medical Center, as part of the Springer Compact agreement.

Conflict of interest

The author has received consultancy fees from Genzyme, Biogen Idec, Teva, Merck Serono and Roche.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Uitdehaag, B.M.J. Disability Outcome Measures in Phase III Clinical Trials in Multiple Sclerosis. CNS Drugs 32, 543–558 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-018-0530-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-018-0530-8