Abstract

Background

Estimating the costs of mental illness provides useful policy and managerial information to improve the quality of life of people living with a mental illness and their families.

Objective

This paper estimates the costs of mental health in Australia using the standard-of-living approach.

Methods

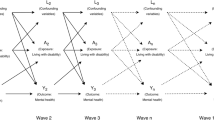

The cost of mental illness was estimated implicitly using a standard-of-living approach. We analysed data from 16 waves of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey (HILDA) using 209,871 observations. Unobserved heterogeneity was mitigated using an extended random-effects estimator.

Results

The equivalised disposable income of people with mental illness, measured by a self-reported mental health condition, needs to be 50% higher to achieve a similar living standard to those without a mental illness. The cost estimates vary considerably with measures of mental illness and standard of living. An alternative measure of mental illness using the first quintile of the SF-36 mental health score distribution resulted in an increase of estimated costs to 80% equivalised disposable income.

Conclusion

People with mental illness need to increase equivalised disposable income, which includes existing financial supports, by 50–80% to achieve a similar level of financial satisfaction to those without a mental illness. The cost estimate can be substantially higher if the overall life satisfaction is used to proxy for standard of living.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the Melbourne Institute [https://melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/hilda/for-data-users].

References

Mechanic D. Mental health and mental illness: definitions and perspectives. 1999.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4329.0.00.006—mortality of people using mental health services and prescription medications, analysis of 2011 data. 2017.

Laplagne P, Glover M, Shomos A. Effects of health and education on labour force participation. In: Commission P, editor. Melbourne 2007.

Lim D, Sanderson K, Andrews G. Lost productivity among full-time workers with mental disorders. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2000;3(3):139–46.

Doran CM, Kinchin I. A review of the economic impact of mental illness. Austr Health Rev. 2019;43(1):43–8.

Scott S, Knapp M, Henderson J, Maughan BJB. Financial cost of social exclusion: follow up study of antisocial children into adulthood. 2001;323(7306):191.

Reddihough DS, Meehan E, Stott NS, Delacy MJ, Medicine ACPRGJD, Neurology C. The National Disability Insurance Scheme: a time for real change in Australia. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58:66–70.

Knapp M. Hidden costs of mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183(6):477–8.

Hu T-W. Perspectives: an international review of the national cost estimates of mental illness, 1990–2003. J Mental Health Policy Econ. 2006;9(1):3–13.

Hawthorne G, Cheok F, Goldney R, Fisher L. The excess cost of depression in South Australia: a population-based study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2003;37(3):362–73.

Heijink R, Noethen M, Renaud T, Koopmanschap M, Polder J. Cost of illness: an international comparison: Australia, Canada, France, Germany and the Netherlands. Health Policy. 2008;88(1):49–61.

Trautmann S, Rehm J, Wittchen HU. The economic costs of mental disorders: do our societies react appropriately to the burden of mental disorders? EMBO Rep. 2016;17(9):1245–9.

Schofield DJ, Kelly SJ, Shrestha RN, Callander EJ, Percival R, Passey ME. How depression and other mental health problems can affect future living standards of those out of the labour force. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(5):654–62.

Marcotte DE, Wilcox-Gök V. Estimating the employment and earnings costs of mental illness: recent developments in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53(1):21–7.

DeNavas-Walt C, Cleveland R, Webster BH. Income in the United States: 2002. In: Bureau USC, editor. Washington D.C.; 2003.

Tarricone R. Cost-of-illness analysis: what room in health economics? Health Policy. 2006;77(1):51–63.

Cullinan J, Gannon B, Lyons S. Estimating the extra cost of living for people with disabilities. Health Econ. 2011;20(5):582–99.

Zaidi A, Burchardt T. Comparing incomes when needs differ: equivalization for the extra costs of disability in the UK. Rev Income Wealth. 2005;51(1):89–114.

Vu X-BB, Khanam R, Rahman M, Nghiem S. The costs of disability in Australia: a hybrid panel-data examination. Toowoomba: University of Southern Queensland; 2019.

Cullinan J, Gannon B, Lyons S. Estimating the extra cost of living for people with disabilities. J Health Econ. 2011;20(5):582–99.

İpek E. The costs of disability in Turkey. J Fam Econ Issues. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-019-09642-2.

Mundlak Y. On the pooling of time series and cross section data. Econometrica. 1978;46(1):69–85.

Summerfield M, Bevitt A, Freidin S, Hahn M, La N, Macalalad N, et al. HILDA user manual—release 16. Melbourne: University of Melbourne, Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research; 2017.

Wooden M, Watson N. The HILDA survey and its contribution to economic and social research (so far). Econ Recrd. 2007;83(261):208–31.

Department of Social Services. Sample sizes and response rates for the Centre studies: Department of Social Services; 2018 [14 March 2019]. https://www.dss.gov.au/about-the-department/national-centre-for-longitudinal-studies/growing-up-in-australia-the-longitudinal-study-of-australian-children-lsac/sample-sizes-and-response-rates-for-the-centre-studies. Accessed 14 Mar 2019.

Groot W, Maassen van den Brink H. The compensating income variation of cardiovascular disease. J Health Econ. 2006;15(10):1143–8.

Morciano M, Hancock R, Pudney S. Disability costs and equivalence scales in the older population in Great Britain. Rev Income Wealth. 2015;61(3):494–514.

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992;30(6):473–483.

McHorney CA, Ware JE, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care Phila. 1993;31:247.

Frijters P, Johnston DW, Shields MA. The effect of mental health on employment: evidence from Australian panel data. Health Econ. 2014;23(9):1058–71.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. National survey of mental health and wellbeing: summary of results. Catalogue NO. 4326.0. Canberra; 2008.

Borah M, Keldenich C, Knabe A. Reference income effects in the determination of equivalence scales using income satisfaction data. Rev Income Wealth. 2016.

Baetschmann G, Staub KE, Winkelmann R. Consistent estimation of the fixed effects ordered logit model. J R Stat Soc Ser A (Stat Soc). 2015;178(3):685–703.

Smith S, Newhouse JP, Freeland MS. Income, insurance, and technology: why does health spending outpace economic growth? Health Aff. 2009;28(5):1276–84.

Pammolli F, Riccaboni M, Magazzini L. The sustainability of European health care systems: beyond income and aging. Eur J Health Econ. 2012;13(5):623–34.

Gelb BD, Corrigan PW. How managers can lower mental illness costs by reducing stigma. Bus Horiz. 2008;51(4):293–300.

Hickie I. Can we reduce the burden of depression? The Australian experience with beyondblue: the national depression initiative. Australas Psychiatry. 2004;12(sup1):s38–46.

Maher B. RU OK?: the role of community in suicide prevention. Berlin: Springer, Global Health Leadership; 2019. p. 79–90.

McGorry PD, Tanti C, Stokes R, Hickie IB, Carnell K, Littlefield LK, et al. headspace: Australia’s National Youth Mental Health Foundation—where young minds come first. Med J Aust. 2007;187(S7):S68–70.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to three anonymous referees, two guest editors and the editor of this journal for their feedback, which has improved the paper. This paper uses unit record data from The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey, which is conducted in partnership between the Department of Social Services (DSS) and the Melbourne Institute. Appropriate ethical approval was gained during the study. The findings and views reported in this paper are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the DSS or the Melbourne Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SN conceived the project idea, requested data, conducted the analysis and prepared the manuscript. RK and BT were involved in discussions to expand the scope of the analyses and edited the manuscript. BV reviewed the literature, prepared data and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study did not receive any funding.

Conflict of interest

Son Nghiem, Rasheda Khanam, Xuan-Binh Vu and Bach Xuan Tran declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nghiem, S., Khanam, R., Vu, XB. et al. Implicitly Estimating the Cost of Mental Illness in Australia: A Standard-of-Living Approach. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 18, 261–270 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-019-00526-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-019-00526-y