Abstract

Background

An individual’s financial situation is a key contributor to their overall well-being. Existing research has examined the direct economic consequences of changes in health upon out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure, participation in the labour force and potential earnings. There is also research exploring an individual’s concern about their subjective financial situation regardless of the level of their income or work status on their health. In contrast, this paper conducts a causal analysis of the effects of general and mental health on an individual’s subjective evaluation of their financial situation controlling for their work status and income. This is of importance because current health policy in the United Kingdom (UK) stresses the role of health as an asset which can mediate the wider flourishing of individuals. Moreover, subjective financial situation comprises a key component of well-being now being measured and sought in social welfare policy.

Methods

Fixed effects instrumental variable panel data regression analysis is applied to 25 years of longitudinal data, from 1991, drawn from the harmonised British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) and Understanding Society Survey (USS).

Results

Improved general health and reduced mental illness both improve the subjective financial situation of males and females. However, these affects diminish across older cohorts of males and females.

Conclusions

Investing in and improving general and mental health can improve the subjective financial situation and hence well-being of individuals. The targeting of health also needs to take account of an individuals’ life-stage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

There is extensive evidence on the socio-determinants of health (SDH) [1]. It is argued that the SDH produce health disparities because, depending on the context, a lack of social and economic resources can reduce access to health care, only permit access to lower quality health care, or encourage engagement in more harmful lifestyles [2, 3].

The association between access to health and objective economic inequality has been investigated broadly through a focus on three issues: access to out-of-pocket healthcare expenses; restricted participation in the labour market; and, reduced potential for earnings. The relative importance of these relationships, however, is country-specific, depending on the healthcare system.

In the United States (US) and Australia individuals with health conditions face out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure. The expenses are found to be associated with an increase in the total number of chronic conditions of individuals [4,5,6,7], but also specific conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Australia [8], cancer in the US [9], high blood pressure, diabetes or depression in Australia [6]. Moreover, poor health is also associated with other costs of illness, such as transportation and configuration of home care environments, in the US [2].

Depression or mood affective disorders, diseases of the respiratory system, diseases of the circulatory system (other than hypertension), heart diseases, and mental and behavioural disorders are also found to be associated with being out of the labour force in Australia [10, 11]. Back problems and arthritis are associated with early retirement in Australia [11]. Being out of the labour force is associated with musculoskeletal conditions in the US [12], multiple sclerosis in Sweden [13] and bipolar disorder in the US [14]. An association between undergoing active cancer care and less likelihood of being employed full-time is also found in the US [15].

Poorer health is also found to be associated with the lower potential to earn income. For example, individuals suffering from multiple health conditions have been found to be associated with lower incomes and possession of less assets, a higher propensity to hold consumer debt, higher risk of cash flow difficulties, dissaving to meet day-to-day living expenses and exclusion from financial providers in Australia [16] and the US [17]. Moreover, episodes of poor health earlier in life through reduced earnings are shown to be negatively associated with the level of pension and social security income during retirement. Finally new health problems, especially severe ones, may lead to people revising their expectations of how long they are going to live, and consequently may encourage a move towards present consumption [2].

The above literature focusses on actual or objective economic inequalities. However, research also recognises that subjective financial well-being is distinct from, for example, objective measures of income in connection with health and well-being [18]. This is because the same level of income may be sufficient for one person’s needs but not another [19]. In part this will be because individuals’ sense of social comparison and expectation underpin differences in the perceived adequacy of income [20], as identified in Mexico, and this in turn is likely to vary across contexts and cultures [21], as for example, shown across Europe.

A focus on subjective financial situation, as opposed to just focussing on income and employment prospects, also takes into account an individual’s capacity to participate in wider social and cultural activities as these may incur costs [22]. Moreover, anxieties that individuals feel when contemplating their financial futures may also play a fundamental role in influencing their well-being and quality of life, as individuals might be affected by the prospect of loss and the fear of experiencing financial hardship, regardless of their current stated economic circumstances. Thus, an individual’s sensitivity to risk is partially, at least, independent of their current income level, as demonstrated in Australia [23].

The relationship between health and subjective financial situation in the United Kingdom (UK) is thus explored in this paper. The context for the research is that there is growing policy development in the UK recognising that health is an asset that allows for the wider flourishing of individuals [24, 25]. Public policy in the UK also emphasises a need to promote the well-being of individuals, of which financial security is a key component [26, 27]. Consequently, this paper conducts a causal analysis of the effects of health on the subjective financial situation of individuals, which is a major contributor to their well-being, controlling for their income, work status and other confounders.

Methods

An instrumental variable fixed effects panel-data analysis is applied to 25 years of longitudinal data, which comprises a combination of 18 years of British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) data from 1991 to 2008, and 7 years of Understanding Society: The UK Household Longitudinal Study survey (USS) data from 2009 to 2015–16. The newer USS dataset has incorporated the older BHPS but also expanded its coverage.

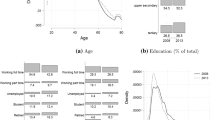

Table 1 identifies and labels the variables that are employed in the analysis. The key confounding variables include: The age of individuals in years as well as age cohorts to which individuals belong, their gender; their education level, measured as having a university degree or not; household composition measured in terms of having a partner or not, and the number of children of varying ages; work status, measured in terms of employment type, being unemployed, as well as being retired, or on maternity leave, caring for the family or being on long-term sick leave (compared to being on a government training scheme or other status); and, current income. This is the level of real gross monthly household income. It is not equivalised but, as noted above, the analysis controls for the presence of a partner and number of children in the household. Work status and income are important as they control for access to the current objective financial and economic resources of individuals.

The key outcome variable is the subjective view of an individual’s financial situation, 'Finnow'. It is measured by the question “How well would you say you yourself are managing financially these days?” Reponses are coded with a five-point Likert scale with the following dimensions: ‘finding it very difficult’, ‘finding it quite difficult’, ‘just about getting by’, ‘doing alright’ and ‘living comfortably’.

Two measures of health are used in the study. The first is a general health variable, measured on a five-point Likert scale. It takes into account an individual’s subjective view of their overall health, and it has been often identified with physical health [28, 29]. However, the response categories across BHPS and USS datasets are different. In the BHPS general health has the following categories: excellent, good, fair, poor and very poor. In the USS the categories are: excellent, very good, good, fair and poor. A synthesised measure was created based on the sample proportions for each category with the following four categories derived: excellent, good, fair, very poor. This new synthesised variable combined the ‘very poor’ and ‘poor’ scales in BHPS and the ‘very good’ and ‘good’ scales of USS. The second health measure is the 12 item General Health Question (GHQ12) which broadly measures mental health [30]. The Likert version is adopted in this study [31,32,33].

Because causal insights are sought, instrumental variables are employed in the analysis. The lagged value of health as well as dummy variables for England, Scotland and Wales compared to Northern Ireland and the Channel Isles are used as instruments. The former measures the health status that has occurred prior to the measurement of the subjective financial situation. The country dummies are assumed to capture the variation in supply of health at the country level. Following the devolution of governments in the countries of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland in 1999, the systems of governance across the countries have evolved in a distinct way [34].

The fixed effects panel-data estimator controls for unobserved individual characteristics, which are assumed to be constant over time, and may determine both health status and financial situation. A fixed effect was also used to control for the different surveys that comprised the combined data and, finally, robust variance-covariance matrix estimates are used to draw inferences to control for heteroscedasticity in the cross-sectional dimension [35]. This will improve the overall precision of estimates and, along with the fixed effect attenuate the effects of differences in the measurement of subjective general health.

In this study, the relevance and validity of the instruments is assessed through two tests [36]. F-tests to assess the joint relevance of the instruments in a regression of the two measures of health on the instruments and other confounding variables. The Hansen-Sargan test is performed to establish if the instrumental variables are correlated with the unobserved errors in the regressions of subjective financial situation on the health measures and other confounding variables. The tests for the relevance and validity of the instruments are reported at the bottom of Tables 2 and 3 which present the regression results. The results of the F-test and Sargan-Hansen test support the relevance and validity of the instruments, respectively. Consequently, causality for the impact of health on financial situation can be inferred.

In order to further interrogate the relationship between subjective financial situation and health, analysis is conducted across different age groups, by including interaction effects between age groups and the health measures, and for males and females separately. The age groups of 16 to 29; 30 to 64 and above 65 are chosen to best reflect distinct stages of life, in part to reflect World Health Organisation (WHO) guidelines. It is also known that financial circumstances and aspirations vary over the life course. Differences between genders may occur as females are found to exhibit lower financial literacy as well as greater vulnerability financially, so health concerns could exacerbate these issues [37]. Furthermore, males may be less likely to seek help with health-related issues and this might particularly be the case with a persisting traditional male role of financial provider [38, 39].

Results

Tables 2 and 3 present the regression results for the health effects, and health effects and health-age interaction effects, on subjective financial situation respectively.

Table 2 indicates that general health has a positive significant effect and mental illness (GHQ12) has a negative significant effect on the individual’s perceived financial situation for the total sample. Similar results are found for males and females. The results in Table 3, where health and age group interactions are also included, further support these effects. For the general health variable on its own, for the whole sample, and then for males and females, the positive coefficients show that improved health leads to improvements in subjective financial situation. For the mental illness (GHQ12) variable on its own, for the whole sample and then for males and females, the negative coefficients show that increases in mental illness reduce an individual’s subjective financial situation.

The interaction effects qualify these effects and show that the above effects diminish across age-cohorts. This is because the coefficients for General health*Age1 and General health*Age2 have negative signs for the whole sample, males, and for females. This means that the positive effect of general health on subjective financial situation is reduced across older cohorts compared to the youngest cohort.

In the case of mental illness (GHQ12), the interaction effects for GHQ12*Age1 and for GHQ12*Age2 for the whole sample, males and for females are positive. This means that the effect of having mental illness that reduces subjective financial situation is less for older cohorts compared to the youngest cohort.

Discussion

Current UK health policy focuses on health as an asset, in the context of integrated care systems and it seeks to promote a more inclusive and productive society, with a focus on the general flourishing of individuals [40, 41]. More general social welfare policy also now promotes the pursuit of well-being of which subjective financial situation is a key component [27].

The literature exploring the relationship between health and financial situation has tended to focus on either the importance of income on health, acknowledging that health can also influence income, and financial burden as a result of out-of-pocket healthcare expenses, restricted participation in the labour market and reduced potential for earnings. The literature has also identified that there are distinct effects of subjective financial well-being on health.

Building on this latter literature, this study focusses on the causal impact of health on subjective financial situation, controlling for the influence of actual income and work status. The advantages of the study are that it draws upon large-scale longitudinal data that facilitated the use of fixed-effects instrumental variable panel-data analysis to identify causal effects. The results show that improvements in general and mental health for both males and females can improve their subjective financial situation. It is also found that the effects change across age groups for both males and females, and that they differ for general health and mental illness. Consequently, these results suggest that linking healthcare to include guidance and advice on the individual’s financial situation particularly across age cohorts, recognising the types of health effects, could enhance well-being and contribute to current health policy objectives [11].

The literature has typically found that older adults exhibit more financial satisfaction than younger adults [42, 43] even at very low levels of income [44]. The above results show that variations in health can qualify these insights. In particular, perhaps through a loss of capability [45], the link between general health and ageing can reduce the positive effect of greater health on the subjective financial situation of individuals. In the case of mental health, however, perhaps through greater resilience, the link between mental illness and reductions in the subjective financial situation of individuals is reduced across ageing cohorts. It is known, for example, that relatively greater social support and links to social organisations in older age groups can counter reductions in mental health through social isolation [46]. It remains that further research is required to identify which health conditions contributing to general health drive the differences compared to mental health to better target policy.

Despite the contributions of the study, the following limitations remain. The synthesised measure of general health has introduced some approximation, which has been partly controlled for by correcting for heteroscedasticity and including a fixed effect to differentiate between the underlying BHPS and USS datasets. Furthermore, due to the long time-series of the data, the availability of instruments was limited and had to be derived from within the data. Although, these instruments passed the diagnostics tests of relevance and validity, further exploration of other instruments could be carried out, for example, acquiring measures of the actual supply-side of healthcare. This is likely to require shorter-time period data as longitudinal data on the availability of healthcare assets is not readily available, but may be extracted, say, from health authority audit data.

Conclusions

Although the SDH are well known, and there has been research that has examined the impact of subjective financial well-being on health, there has been no research on the reverse impacts of health on the subjective financial situation of individuals, which is linked to their well-being. This is important in the context in which health is viewed as an asset that can have cross-cutting impacts across all domains of individuals’ lives and, moreover, that subjective financial well-being is considered to be an important feature of well-being which is now monitored as part of UK social welfare policy. Health is likely to influence an individual’s well-being based on their feelings of their subjective financial situation regardless of the level of income and employment status. This is because the latter will not fully measure the sufficiency of access to resources to meet an individuals’ needs, their sense of social comparison and expectations connected with differences in income and work status as well as potential future challenges.

This paper has identified that improvements in both general health and reductions in mental illness can improve the subjective financial situation of both males and females. However, in the case of general health the improvement can reduce across ageing cohorts. In the case of mental health, the negative influence of mental illness on subjective financial situation, is reduced across ageing cohorts. This insight provides evidence in favour of linking health care to employment policy and financial advice and support for individuals. However, this needs to be nuanced depending on the health conditions and stage of the life course. The impact of these needs to be further researched.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the UK Data Archive Study Number 6614 https://beta.ukdataservice.ac.uk/datacatalogue/studies/study?id=6614, https://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-6614-12

Abbreviations

- SDH:

-

Social Determinants of Health

- BHPS:

-

British Household Panel Survey

- USS:

-

Understanding Society Survey

- GHQ12:

-

12 item General Health Questionnaire

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- US:

-

United States

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

References

Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(1_suppl2):19–31.

Smith JP. 10. Healthy Bodies and Thick Wallets. J Econ Perspect. 1999;13(2):144–66 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15179962. [cited 2019 Sep 5].

Marmot M. Social determinants of public health. Lancet. 2005;365:1099–104.

Hwang W, Weller W, Ireys H, Anderson G. Out-of-pocket medical spending for care of chronic conditions. Health Aff. 2001;20(6):267–78.

Paez KA, Zhao L, Hwang W. Rising out-of-pocket spending for chronic conditions: a ten-year trend. Health Aff (Millwood). 28(1):15–25 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19124848. [cited 2019 Sep 3].

Mofizul Islam M, Yen L, Valderas JM, McRae IS. Out-of-pocket expenditure by Australian seniors with chronic disease: the effect of specific diseases and morbidity clusters. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1008.

McRae I, Yen L, Jeon YH, Herath PM, Essue B. Multimorbidity is associated with higher out-of-pocket spending: a study of older Australians with multiple chronic conditions. Aust J Prim Health. 2013;19(2):144–9.

Essue B, Kelly P, Roberts M, Leeder S, Jan S. We can’t afford my chronic illness! The out-of-pocket burden associated with managing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in western Sydney, Australia. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2011;16(4):226–231. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21954233. [cited 2019 Sep 3].

Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health Aff. 2009;28(5):822–31.

Callander EJ, Schofield DJ, Shrestha RN. Multi-dimensional poverty in Australia and the barriers ill health imposes on the employment of the disadvantaged. J Socio Econ. 2011;40(6):736–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2011.08.001.

Schofield DJ, Shrestha RN, Passey ME, Earnest A, Fletcher SL. Chronic disease and labour force participation among older Australians. Med J Aust. 2008;189(8):447–50.

Yelin EH, Trupin LS, Sebesta DS. Transitions in employment, morbidity, and disability among persons ages 51-61 with musculoskeletal and non-musculoskeletal conditions in the US, 1992-1994. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(4):769–79.

Henriksson F, Jönsson B. The Economic Cost of Multiple Sclerosis in Sweden in 1994. Pharmacoeconomics. 1998;13(5):597–606. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-199813050-00012 [cited 2019 Sep 5].

Begley CE, Annegers JF, Swann AC, Lewis C, Coan S, Schnapp WB, et al. The Lifetime Cost of Bipolar Disorder in the US. Pharmacoeconomics. 2001;19(Parts 1 and 2):483–95.

The Personal Financial Burden of Cancer for the Working-Aged Population. Available from: https://www.ajmc.com/journals/issue/2009/2009-11-vol15-n11/ajmc_09nov_finkelstein801to806. [cited 2019 Sep 5].

Temple JB, Williams R. Financial well-being of older Australians with multiple health conditions. Australas J Ageing. 2018;37(2):127–34 Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/ajag.12497. [cited 2019 Sep 3].

Svynarenko R, Zhang Q, Kim H. The financial burden of Cancer: financial ratio analysis. J Fam Econ Issues. 2019;40(2):165–79.

Arber S, Fenn K, Meadows R. Subjective financial well-being, income and health inequalities in mid and later life in Britain. Soc Sci Med. 2014;100:12–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.10.016.

Kahn JR, Fazio EM. Economic Status Over the Life Course and Racial Disparities in Health. J Gerontol Ser B. 2005;60(Special_Issue_2):S76–84.

Angel RJ, Angel JL. Financial Strain and Health among Elderly Mexican-Origin Individuals Author (s): Ronald J. Angel, Michelle Frisco, Jacqueline L. Angel and David A. Chiriboga Published by: American Sociological Association Stable. 2003;44(4):536–51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/. Accessed 23 June 2020.

Whelan CT, Maître B. Material deprivation, economic stress, and reference groups in Europe: an analysis of EU-SILC 2009. Eur Sociol Rev. 2013;29(6):1162–74.

Lee MP, Sabri MF. Review of financial vulnerability studies. Arch Bus Res 2017 25;5(2).

Rohde N, Tang KK, Osberg L, Rao DSP. Is it vulnerability or economic insecurity that matters for health? J Econ Behav Organ. 2017;134:307–19.

Hanlon P, Carlisle S, Hannah M, Reilly D, Lyon A. Making the case for a “fifth wave” in public health. Public Health. 2011;125(1):30–6.

Baker D. Developing and implementing a robust asset-based approach to public health. Perspect Public Health. 2014;134(3):129–30.

Hicks S, Tinkler L, Allin P. Measuring subjective well-being and its potential role in policy: perspectives from the UK Office for National Statistics. Soc Indic Res. 2013;114(1):73–86.

Office for National Statistics. Measures of National Well-being Dashboard. 2019.

Meltzer H. General Measures of Health for use in Health Interview Surveys and Censuses : the UK experience Washington Group meeting; 2003.

Yu G, Sessions JG, Fu Y, Wall M. A multilevel cross-lagged structural equation analysis for reciprocal relationship between social capital and health. Soc Sci Med. 2015;142:1–8.

Gnambs T, Staufenbiel T. The structure of the general health questionnaire (GHQ-12): two meta-analytic factor analyses. Health Psychol Rev. 2018;12(2):179–94.

Sage D. Do active labour market policies promote the well-being, health and social Capital of the Unemployed? Evidence from the UK. Soc Indic Res. 2015;124(2):319–37.

Araya R, Dunstan F, Playle R, Thomas H, Palmer S, Lewis G. Perceptions of social capital and the built environment and mental health. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(12):3072–83.

Cassidy T, McLaughlin M, McDowell E. Bullying and health at work: the mediating roles of psychological capital and social support. Work Stress. 2014;28(3):255–69.

Bevan G, Karanikolos M, Exley J, Nolte E, Connolly S, Mays N. The four health systems of the UK: how do they compare? Source report; 2014.

Colin Cameron A, Miller DL. A practitioner’s guide to cluster- robust inference. J Hum Resour. 2015;50(2):317–72.

Baum CF, Schaffer ME, Stillman S. Instrumental variables and GMM : Estimation and testing, vol. 1; 2003. p. 1–31.

Fonseca R, Mullen KJ, Zamarro G, Zissimopoulos J. What explains the gender gap in financial literacy? The role of household decision making. J Consum Aff. 2012;46(1):90–106.

Galdas PM, Cheater F, Marshall P. Men and health help-seeking behaviour: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49(6):616–23.

Ciccia R, Verloo M. Parental leave regulations and the persistence of the male breadwinner model: using fuzzy-set ideal type analysis to assess gender equality in an enlarged Europe. J Eur Soc Policy. 2012;22(5):507–28.

Sigerson D, Gruer L. Asset-based approaches to health improvement. NHS Scotl. 2011.

NHS England. The NHS Long Term Plan – a summary; 2019. p. 2.

Hansen T, Slagsvold B, Moum T. Financial satisfaction in old age: a satisfaction paradox or a result of accumulated wealth? Soc Indic Res. 2008;89(2):323–47.

Hsieh CM. Trends in financial satisfaction among middle-age and old-age Americans, 1972-1996. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2000;51(2):105–13 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11140846. [cited 2020 Jan 14].

Stoller MA, Stoller EP. Perceived Income Adequacy among Elderly Retirees. J Appl Gerontol. 2003;22(2):230–51 Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0733464803022002004. [cited 2020 Jan 14].

Beard JR, Officer A, De Carvalho IA, Sadana R, Pot AM, Michel JP, et al. The world report on ageing and health: a policy framework for healthy ageing. Lancet. 2016;387(10033):2145–54.

Rohde N, D’Ambrosio C, Tang KK, Rao P. Estimating the mental health effects of social isolation. Appl Res Qual Life. 2016;11(3):853–69.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding for this study came from The Health Foundation as part of their Research programme on the Social and Economic Value of Health https://www.health.org.uk/funding-and-partnerships/programmes/the-social-and-economic-value-of-health (Award ID: 773005). The design of the research is the sole responsibility of the authors. Feedback on the research outcomes was provided through discussions with a project advisory board at The Health Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PD planned the analysis and provided the final draft of the paper. SR contributed to the development of the analysis and developed the draft of the paper. HK undertook the data analysis under the supervision of PD and SR. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Relevant ethical approval of the research was obtained through Loughborough University’s Ethics Approvals (Human Participants) Sub-Committee https://www.lboro.ac.uk/committees/ethics-approvals-human-participants/additionalinformation/applicationformsandtemplatesfordownload/ under HPSC Reference Number: C18–09. Written informed consent was not required from each participant as the data for the harmonised BHPS/USS was accessed under a standard End User Licence arrangement for an academic research project as the data are fully anonymised https://www.ukdataservice.ac.uk/get-data/how-to-access/conditions.aspx.

Consent for publication

No consent for publication was required as the data are freely available for academic research from the UK Data Archive https://www.data-archive.ac.uk/.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Downward, P., Rasciute, S. & Kumar, H. Health, subjective financial situation and well-being: a longitudinal observational study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 18, 203 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01456-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01456-3