Abstract

Purpose of Review

In this work, we aim to highlight original research publications within the past 5 years that address performance improvement (PI) for emergency general surgery (EGS).

Recent Findings

In 2022, the AAST and the American College of Surgeons launched the EGS verification program and the EGS standards manual—Optimal Resources for Emergency General Surgery. The key elements of EGS PI include: a data registry, personnel, clinical practice guidelines, PI events, and a peer review process.

Summary

While EGS represents a substantial burden of hospitalization and spending, public funding does not match other surgical subspecialties. For effective PI, EGS programs will need a combination of funding for support personnel and EMR-based registry solutions which accurately capture all patients cared for by EGS teams, operatively and non-operatively. This must be reproducible in all hospitals who care for patients with EGS-related diagnoses, not just tertiary care facilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is estimated that 2.5 to 4 million patients are admitted each year in the United States with emergency general surgery (EGS) conditions. The incidence of disease is 1290 per 100,000 admissions, which is higher than other significant comorbidities admitted individually including diabetes, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure [1]. Process improvement (PI) is a dynamic method of analyzing and reviewing practice patterns in order to improve the quality of healthcare and clinical outcomes [2]. In 2010, Oolga et al. performed a retrospective analysis of the National Inpatient Sample data and identified significant variations in risk adjusted outcomes of EGS patients across hospitals, with several thousand higher than expected number of deaths nationwide. They concluded a EGS quality improvement program for risk adjusted benchmarks of hospitals for EGS patients was needed [3].

In 2012, this variability in outcomes and processes of care for EGS patients led to a national call by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) to study, systematize, create quality improvement (QI) processes, and analyze outcomes in EGS with the same rigor as trauma [4,5,6]. The AAST Committee on Severity Assessment and Patient Outcomes took this momentum a step further, and sought to clearly define the primary EGS diagnoses so that the field could be carefully circumscribed. Using Delphi methodology, a consensus summary of clinical conditions encompassing EGS was created (Table 1) [7].

Following this, the AAST and the American College of Surgeons (ACS) launched the EGS Verification Program. This was accompanied by the EGS standards manual titled Optimal Resources for Emergency General Surgery [2, 8]. This program and manual emphasize the diverse scope of EGS including the unique experience of EGS patients and providers. They also specify what processes of care must be in place to ensure quality care.

The current manuscript seeks to summarize the current thinking and practice around performance improvement processes for EGS in the modern era. This includes relevant literature as well as a summary of the author’s experiences.

Current State of EGS PI

In 2022, the AAST and the American College of Surgeons launched the EGS verification program and the EGS standards manual—Optimal Resources for Emergency General Surgery [6, 8]. As mentioned, this manual emphasizes the diverse scope of EGS including the unique experience of EGS patients and providers. DeGirolamo et al. used the technique of process mapping to gain insight caring for a particular subset of EGS patients, small bowel obstructions. Process mapping follows patients through their hospital journey, documenting interactions with the hospital system. This method allows providers to notice every small step to identify areas of variation or future improvement. Insights from process mapping have driven QI advances in cardiac surgery, otolaryngology, and orthopedic surgery.[9].

The EGS standards manual authors recognize the value of clinically relevant EGS data to drive quality improvement. Capturing clinical data on EGS patients requires a strategy that identifies patients undergoing surgical procedures and those treated non-operatively. A multi-disciplinary approach to care and quality, with involvement of the full array of care team members and hospital settings serving EGS patients is needed [6, 8].

Key Elements of EGS PI

The EGS patient has a much higher morbidity and mortality compared to a non-emergency, elective general surgery patient with respect to infection, multiple organ system derangement, and medical error.[10] Consistency in the use of PI and verifying EGS standards in practice is vital to improve the system of care for EGS patients.[6] The key elements of EGS PI are similar to any structured PI system and include: (1) a data registry, (2) dedicated personnel, (3) clinical practice guidelines, (4) flagging specified PI events, and (5) a peer review process [11].

Data is critical to any PI effort. The data registry should include captured demographics, diagnoses, comorbidities, procedural characteristics, length of stay, outcomes, and adverse events. Personnel to maintain such a registry and the various levels of oversight needed in a successful PI system include at the very least a medical director (trauma and acute care surgeon), a program manager (oversees the trauma and EGS programs/initiatives), and a registrar (responsible for data abstraction).[11].

As practice patterns vary on the provider level, institutional clinical practice guidelines should be developed for standardization of the management of common EGS problems. A call for national, evidence-based recommendations will ultimately be needed, similar to those in trauma. Standardizing practice through protocols and guidelines has been shown to improve outcomes in other diseases [12,13,14]. While it is important that EGS guidelines are used, it is equally important that they acknowledge the heterogeneity in patients and practice patterns. For example, in private practice around the country, many surgical patients are admitted by hospitalists and general surgeons serve as consultants. In an academic center, surgical services tend to admit those patients. Guidelines for specific conditions must be congruent with the dominant coverage models while adhering to principles of disease management.

EGS process improvement events should be flagged via registry filters [10]. AAST has developed a standardized anatomic severity grading scale for 16 common EGS conditions. This framework was designed to facilitate risk stratification, QI, outcome analysis, and resource management [15]. A multidisciplinary, peer review process should follow consisting of a peer group of general and acute care surgeons to evaluate the registry for captured events of interest for standards of care and outcome deviations (Table 2). Similar to the process recommended for trauma centers, all events should be reviewed, documented, and monitored. Levels of review include primary, secondary, and tertiary, see the EGS standards manual for more details [6, 8].

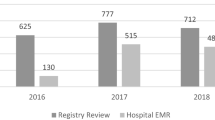

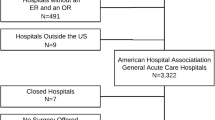

Building a Registry

Central to any PI effort is the creation and maintenance of an accurate patient registry. This enables an EGS group to monitor volume and complication rates. As well, this data can be compared to national benchmarks to evaluate observed to expected morbidity and mortality rates. As such, a registry is of utmost importance [6]. The creation and maintenance of a registry is quite challenging. Compared to a trauma service, which often has funded positions for program managers, performance improvement personnel, and registrars, EGS services typically lack these resources. Several groups have utilized ICD and CPT code-based identification systems, as well as EMR-based registry creation, but these have yet to become standard [16, 17].

An additional challenge of registry creation is that much of the EGS patient population is managed nonoperatively. NSQIP has added an EGS module to its data collection and reporting system, but those patients managed nonoperatively may not be accounted for in this database. While NSQIP EGS data reveals 27% of the population is managed nonoperatively, other institutional series show more than 50% of patients are managed nonoperatively [7, 18, 19]. While several series have found NSQIP to be a cost-effective pursuit for a hospital or system, the added costs of either participation or entry of all EGS patients are not trivial and may remain a barrier to uniform participation [20, 21].

As a result, a significant national effort must be put forth to create a reproducible registry system which is nationally available, captures all patients managed by EGS services (both operatively and nonoperatively), and is affordable and feasible to implement in the absence of support personnel afforded to trauma services.[22].

Multidisciplinary EGS PI and Peer Review

As with any PI or peer review effort, it is important to uphold the quality of all care provided. Similar to other areas of Acute Care Surgery, EGS PI involves a multidisciplinary approach which requires input and collaboration from all appropriate stakeholders. In EGS PI, these stakeholders include, but are not limited to, Emergency Medicine, Radiology, Anesthesia, and Gastroenterology. Monthly morbidity and mortality (M&M) cases with opportunities for improvement should be reviewed via a standardized process prior to this meeting. This multidisciplinary PI review should occur at least monthly with a required 50% attendance rate.

The meeting should open with a legal disclosure with language adjustment per institution and state, for example, “This multidisciplinary conference is a joint venture between the Division of Acute Care Surgery and Departments of Emergency Medicine, Radiology, Anesthesia, and Gastroenterology. The discussions and interactions held in this conference are strictly for educational and quality improvement/review purposes only. This conference is established with the purpose of evaluating and improving the quality of care. This information is privileged & confidential under XX Law, attorney client privileges and other applicable laws, and shall not be disclosed to unauthorized persons.” The meeting should then follow with structure or systems updates and input from the assigned liaisons followed by M&M discussion with emphasis on opportunities for improvement.

The Future of EGS PI

In line with the American College of Surgeons Quality Verification Program (ACS QVP), the ACS EGS Verification has been launched, with the verification of five pilot sites. The verification standards have been outlined in Optimal Resources in Emergency General Surgery, many of which mirror the verification standards in Trauma, Cancer, Pediatric Surgery, and other specialty verification programs through the ACS [8]. Many programs are, at the time of the preparation of this manuscript, preparing and applying for verification.

However, for many reasons mentioned earlier in this manuscript, this process will remain a challenge. There are several barriers to widespread dissemination of EGS quality programs and PI processes. For one, there is no uniform practice for the care of EGS patients across the country. While EGS represents a substantial burden of hospitalization and hospital spending, public funding does not match that of other surgical subspecialties [3, 23]. To run effective PI programs, EGS programs will need a combination of funding for support personnel, such as program managers and registrars, as well as EMR-based registry solutions which accurately capture all patients cared for by EGS teams, both operatively and nonoperatively [22]. This must be reproducible in all hospitals who care for patients with EGS-related diagnoses, not just tertiary care facilities. Without this, EGS will continue to lag behind other subspecialties in the pursuit of effective PI.

Conclusions

Effective PI programs will be essential in driving quality in EGS. There is a national movement to implement this, driven by the American College of Surgeons EGS Verification Program. However, creation and maintenance of these programs requires additional personnel and a registry, which can be quite expensive and may limit proliferation of these programs. Future direction requires cost-effective systems which can make them accessible to all hospitals.

References

Gale SC, Shafi S, Dombrovskiy VY, Arumugam D, Crystal JS. The public health burden of emergency general surgery in the United States: A 10-year analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample—2001 to 2010. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77(2):202–8.

American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patient. Chicago, American College of Surgeons, 2022. This article defined process improvement.

Ogola GO, Gale SC, Haider A, Shafi S. The financial burden of emergency general surgery: national estimates 2010 to 2060. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79(3):444–8.

Morris JA Jr, Fildes J, May AK, Diaz J, Britt LD, Meredith JW. A research agenda for emergency general surgery: clinical trials. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(1):329–33.

Morris JA Jr, Fildes J, May AK, Diaz J, Britt LD, Meredith JW. A research agenda for emergency general surgery: health policy and basic science. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(1):322–8.

Ross SW, Reinke CE, Ingraham AM, Holena DN, Havens JM, Hemmila MR, et al. Emergency general surgery quality improvement: a review of recommended structure and key issues. J Am Coll Surg. 2022;234(2):214–25.

Shafi S, Aboutanos MB, Agarwal S Jr, Brown CV, Crandall M, Feliciano DV, et al. Emergency general surgery: definition and estimated burden of disease. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(4):1092–7.

American College of Surgeons Emergency General Surgery Verification Program. Optimal Resources for Emergency General Surgery. Chicago, American College of Surgeons, 2022. This document was very important to include as its the EGS standards manual for the ACS EGS Verification program.

DeGirolamo K, D’Souza K, Hall W, Joos E, Garraway N, Sing CK, et al. Process mapping as a framework for performance improvement in emergency general surgery. Can J Surg. 2018;61(1):13–8.

Bradley MJ, Kindvall AT, Humphries AE, Jessie EM, Oh JS, Malone DM, et al. Development of an emergency general surgery process improvement program. Patient Saf Surg. 2018;12:17.

Bozzay J, Bradley M, Kindvall A, Humphries A, Jessie E, Logeman J, et al. Review of an emergency general surgery process improvement program at a verified military trauma center. Surg Endosc. 2018;32(10):4321–8.

Ban KA, Berian JR, Ko CY. Does Implementation of Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) protocols in colorectal surgery improve patient outcomes? Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2019;32(2):109–13.

Federspiel JJ, Eke AC, Eppes CS. Postpartum hemorrhage protocols and benchmarks: improving care through standardization. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2023;5(2s):100740.

Pędziwiatr M, Mavrikis J, Witowski J, Adamos A, Major P, Nowakowski M, et al. Current status of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol in gastrointestinal surgery. Med Oncol. 2018;35(6):95.

Tominaga GT, Staudenmayer KL, Shafi S, Schuster KM, Savage SA, Ross S, et al. The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma grading scale for 16 emergency general surgery conditions: disease-specific criteria characterizing anatomic severity grading. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81(3):593–602.

Becher RD, Meredith JW, Chang MC, Hoth JJ, Beard HR, Miller PR. Creation and implementation of an emergency general surgery registry modeled after the National Trauma Data Bank. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214(2):156–63.

Mou Z, Sitapati AM, Ramachandran M, Doucet JJ, Liepert AE. Development and implementation of an automated electronic health record-linked registry for emergency general surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2022;93(2):273–9.

Matevish LE, Medvecz AJ, Ebersole JM, Wanderer JP, Eastham SC, Dennis BM, et al. The silent majority of emergency general surgery: an assessment of consult and operative volumes. J Surg Res. 2021;259:217–23.

Wandling MW, Ko CY, Bankey PE, Cribari C, Cryer HG, Diaz JJ, et al. Expanding the scope of quality measurement in surgery to include nonoperative care: results from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program emergency general surgery pilot. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83(5):837–45.

Fansi A, Ly A, Mayrand J, Wassef M, Rho A, Beauchamp S. Economic impact of the use of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2021;37:e38.

Guillamondegui OD, Gunter OL, Hines L, Martin BJ, Gibson W, Clarke PC, et al. Using the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the Tennessee Surgical Quality Collaborative to improve surgical outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214(4):709–14.

Ashley DW, Mullins RF, Dente CJ, Johns TJ, Garlow LE, Medeiros RS, et al. How much green does it take to be orange? Determining the cost associated with trauma center readiness. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;86(5):765–73.

Tennessee Trauma Center Funding Law. TN Code § 68-59-105 (2021)

Funding

There is no funding to report for this submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in the design, research, and writing of this guideline, as well as critical revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Research Involving Human and Animal Rights

There is not involvement of human or animal subjects.

Informed Consent

There is not requirement of informed consent for this review manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Appelbaum, R.D., Smith, M.C. & Staudenmayer, K.L. Emergency General Surgery Process Improvement Review. Curr Surg Rep (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40137-024-00423-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40137-024-00423-x