Abstract

Introduction

Epidemiologic data on age-related macular degeneration (AMD) are mainly based on cohort studies, including both diagnosed and undiagnosed cases. Using health claims data allows estimating epidemiological data of diagnosed subjects with AMD within the health care system using diagnosis codes from a regional claims database (AOK PLUS) to estimate the prevalence and incidence of non-exudative and exudative AMD in Germany.

Methods

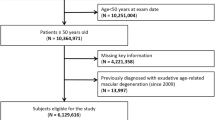

Patients with AMD were identified among AOK PLUS insured patients based on at least two outpatient, ophthalmologic or one inpatient H35.3 diagnoses for the years 2012 to 2021. Patients without continuous observation in a calendar year were excluded. Prevalence was assessed, and 1-year cumulative incidence was determined by the number of newly diagnosed patients divided by the number of individuals at risk. For 2020 and 2021, the AMD stage was assessed by diagnostic subcodes for non-exudative and exudative AMD, respectively. For 2012 to 2019, patient numbers were estimated based on the average proportions of non-exudative AMD and exudative AMD, respectively, in 2020 and 2021. Incidence and prevalence numbers were then extrapolated to Germany.

Results

Between 2012 to 2021, the prevalence of diagnosed AMD cases remained relatively stable among approximately 3.27 million AOK PLUS insured persons, ranging from 0.96% (minimum in 2021) to 1.31% (maximum in 2014) for non-exudative AMD, about twice as high as for exudative AMD (min–max: 0.53–0.72%). The age- and sex-adjusted projections amounted to 644,153 diagnosed non-exudative and 367,086 diagnosed German patients with exudative AMDs in 2021. The 1-year cumulative incidence for non-exudative and exudative AMD, respectively, ranged from 122,427–142,932 to 46,092–86,785 newly diagnosed cases.

Conclusion

The number of diagnosed cases with AMD in Germany has increased slightly over the past decade. For the first time, patient counts with non-exudative and exudative AMD were approximated for Germany based on a representative, large-scale database study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

The study aims to estimate the number of patients with exudative and non-exudative age-related macular degeneration (AMD) in the German health care system (total population and patients with statutory health insurance). |

Additionally, the study provides prevalence and incidence estimates of diagnosed AMD cases that are representative of Germany based on observational data from routine practice. |

What did the study ask? |

The study asks comprehensively what the prevalence of patients with diagnosed non-exudative and exudative AMD in Germany and the risk of being diagnosed with AMD (stratified by age and sex) are. |

Thus, the study aims to give an overview of the real-world numbers of diagnosed AMD cases in Germany. |

What was learned from this study? |

This study describes the prevalence and incidence of diagnosed AMD in Germany over the last decade and describes the proportion of patients with non-exudative and exudative AMD within the healthcare system, providing important information regarding patients with AMD numbers in Germany especially if new therapies were available to treat these patients. |

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is one of the most common causes of visual impairment in the elderly population of high-income countries, including Germany [1,2,3]. In 2020, it affected approximately 200 million people worldwide, and, due to population aging, this is expected to increase to 288 million cases by 2040 [4]. Commonly known risk factors for AMD include increased age, white race and ethnicity, smoking and genetic factors [5, 6].

AMD can be classified as exudative (“wet”) AMD and non-exudative (“dry”) AMD. Most people with AMD have the non-exudative form, which includes early and intermediate stages of AMD as well as the advanced form called geographic atrophy (GA) [7,8,9]. Another advanced form is exudative AMD. Hence, GA and exudative AMD develop from intermediate stages of non-exudative AMD and are not mutually exclusive, such that both late AMD stages can develop in the same eye [10, 11]. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) therapy is the current standard of care in exudative AMD. GA is characterized by scattered or confluent sharply demarcated lesions resulting from loss of photoreceptors, retinal pigment epithelium cells and the underlying choriocapillaris [12]. It is a continuously progressing disease, whose atrophic lesions typically first occur in the non-subfoveal region and expand to involve the fovea, leading to central scotomas and ultimately to loss of central vision [13]. Until February 2023, no therapies were available that could halt or delay the continuous progression of non-exudative AMD. As the first treatment option in non-exudative AMD, the FDA approved the intravitreal use of pegcetacoplan for patients with GA living in the USA [14]. Right after that, in August 2023, the FDA approved a second GA treatment option, avacincaptad pegol [15]. For both, a marketing authorization in the European Union is currently in progress.

Although AMD is a common disease with considerable individual and societal impact, epidemiologic data on diagnosed AMD are sparse in Germany, in particular for non-exudative AMD. Nonetheless, estimates of patients with AMD numbers are important for planning healthcare resource allocation. Therefore, the aim of this retrospective cohort study based on administrative claims data was to estimate prevalence and incidence of patients diagnosed with exudative or non-exudative AMD in Germany.

Methods

Study Design

This is a retrospective observational cohort study based on an anonymized dataset of patients diagnosed with AMD obtained from a regional statutory health insurance (SHI) fund in Germany (AOK PLUS). In 2021, the AOK PLUS database covered approximately 3.27 million persons living in two administrative regions (states) in Germany (Saxony and Thuringia) [16]. Accordingly, the database represented 4.5% of the SHI population in Germany (N=73,318,711) and 3.9% of the total population in Germany (N= 83,024,481) in 2021 [16, 17]. Previous research has confirmed that the age and comorbidity characteristics of patients insured by AOK PLUS are similar to those of the general German population insured by other SHI funds [18,19,20,21].

The dataset contains data on:

-

(1)

Patients’ demographics (age, sex, date of death),

-

(2)

Outpatient care, including diagnosis codes (based on the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, German Modification: ICD-10-GM) stratified by specialty according to German physician codes (“Facharztgruppenschlüssel”, FGS), and performed interventions according to the German operation and procedure classification system [OPS],

-

(3)

Inpatient care (hospitalizations, length of stay, procedures [OPS], diagnosis codes [ICD-10-GM]) and

-

(4)

Outpatient drug prescriptions (reimbursed drug dispensing by pharmacies according to anatomical therapeutic chemical [ATC] codes).

Study Population

Research and analysis were conducted on anonymized data provided by AOK PLUS under formal agreement and in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. No research was conducted on human subjects. In accordance with German laws (§ 75 of Book 10 of the German Code of Social Law [SGB X]), the use of such data is not subject to ethics committee approval, because conclusions about individual patients are excluded and only aggregated results are presented. No patient authorization was required because solely deidentified data were analyzed.

All patients diagnosed with AMD (ICD-10 H35.3) between 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2021 were included in this study. For each calendar year, diagnosed prevalence of any AMD was determined by at least one inpatient H35.3 diagnosis and/or at least two outpatient H35.3 diagnoses documented by an outpatient ophthalmologist (FGS code 05) in two different quarters within 2 years (which included the year of interest and the year before), whereby at last one of these diagnoses had to fall in the year under consideration. Inpatient diagnoses are considered more reliable than outpatient ones because hospitals have controls for coding in place, while private practices do not. To ensure reliability of the detected diagnoses in RWE studies, it is common practice to use at least two outpatient diagnoses as an inclusion criterion, while one inpatient diagnosis suffices [22]. In the outpatient setting, an identical diagnosis is reported only once per quarter and per patient. Hence, detection of at least two diagnoses must be spread over two quarters. A longer inclusion period was set for identification of non-exudative AMD because early stages of non-exudative AMD do not need regular short-term (i.e., quarterly) observations and patients with non-exudative AMD would be less likely to see an ophthalmologist than patients with exudative AMD because of the lack of available therapeutic options. To determine the annual prevalence as of December 31 of each calendar year, patients diagnosed with AMD and individuals without any AMD had to be continuously insured with AOK PLUS in the year of interest and had to be alive on December 31 of the respective year.

To determine the annual cumulative incidence between 2012 and 2021, patients newly diagnosed with any AMD (incident cases) and individuals at risk for AMD were identified in each calendar year by applying the following additional selection criteria: (i) the 2 years in which the AMD diagnoses (H35.3) were reported included the year of interest and the year after, whereby the first diagnosis had to fall in the year under consideration, (ii) no diagnosis of AMD (H35.3) in two calendar years preceding the year under consideration (to ensure it is an incident case) and (iii) continuous insurance at AOK PLUS in the 2 calendar years preceding the first diagnosis of macular degeneration (to ensure that the non-documented diagnoses were not due to non-existent coverage by AOK PLUS).

The prevalence of exudative and non-exudative AMD was determined by ICD-10 subcodes specific for exudative AMD and non-exudative AMD in 2020 and 2021 as these codes were established only in the year 2020. Patients were assigned to a subgroup of patients with AMD if the following conditions were met:

Exudative AMD in 2020

-

ICD-10 H35.30 confirmed by at least one inpatient diagnosis and/or two outpatient diagnoses as documented by an outpatient ophthalmologist in two different quarters between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2020.

-

For incident cases only: No prior diagnosis of macular degeneration (ICD-10 H35.3) in the calendar year before the first H35.30 diagnosis (i.e., from 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2019).

Exudative AMD in 2021

-

ICD-10 H35.30 confirmed by at least one inpatient and/or two outpatient diagnoses as documented by an outpatient ophthalmologist in two different quarters between 1 January 2021 and 31 December 2021.

-

For incident cases only: No prior diagnosis of macular degeneration (ICD-10 H35.3) in the calendar year before the first H35.30 diagnosis (i.e., from 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2020).

Non-exudative AMD in 2020

-

ICD-10 H35.3 confirmed by at least one inpatient and/or two outpatient diagnoses as documented by an outpatient ophthalmologist in two different quarters between 1 January 2019 and 31 December 2020, whereby at least one of them must be a non-exudative AMD diagnosis (H35.31) and fall between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2020.

-

For incident cases only: ICD-10 H35.31 confirmed by at least one inpatient and at least two outpatient diagnoses as documented by an outpatient ophthalmologist between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2021, whereby the first diagnosis must fall between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2020. No prior prescription of anti-VEGF agents or documentation of photodynamic therapy between 1 January 2019 and 31 December 2019 (see Supplementary Materials Table S1 for respective code identifiers).

Non-exudative AMD in 2021

-

ICD-10 H35.31 confirmed by at least one inpatient and/or two outpatient diagnoses as documented by an outpatient ophthalmologist between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2021, whereby at least one of them had to fall between 1 January 2021 and 31 December 2021.

Dual assignment to exudative and non-exudative subgroups was allowed if both stages were documented in a given calendar year.

Of note, the ICD-10 code H35.3, named ‘degeneration of macula and posterior pole,’ covers patients with AMD as well as patients with unspecified degeneration of the macula and posterior pole. In 2020, more differentiated codes were introduced specifying exudative AMD by H35.30, non-exudative AMD by H35.31, ‘other degeneration of macula and posterior pole’ by H35.38 and ‘degeneration of macula and posterior pole, unspecified’ by H35.39. Hence, for 2020 and 2021, proportions for H35.30 coding among H35.3 codes and for H35.31 coding among H35.3 codes were determined and then used to estimate the epidemiologic outcomes for exudative and non-exudative AMD from 2012 to 2019, assuming these proportions remained constant during the 10-year study period. This allowed to exclude patients with other or unspecified degeneration of the macula and posterior pole (H35.38, H35.39) from the prevalence and incidence calculations. For 2020 and 2021, the epidemiologic outcomes were addressed directly using the specific codes for exudative and non-exudative AMD.

Statistical Methods

Point prevalence: The prevalence of exudative and non-exudative AMD was obtained as a point estimate on December 31 of each calendar year between 2012 and 2021 and was calculated using the following formula:

Cumulative incidence: One-year cumulative incidence was estimated for exudative AMD for each calendar year between 2012 and 2021 and for non-exudative AMD for the calendar years between 2012 and 2020. An estimate of incident cases with non-exudative AMD for 2021 could not be determined because data from 2022 would have been required to observe a second confirmed outpatient diagnosis within 2 years, which was not available at the time of the study. The cumulative incidence was defined as the number of newly diagnosed patients divided by the total number of individuals at risk using the following formula:

To determine the cumulative incidence and point prevalence of exudative and non-exudative AMD for 2012 to 2019, patient numbers were projected based on the 2020 and 2021 ratios of exudative AMD (H35.30) to any AMD (H35.3) and non-exudative AMD (H35.31) to any AMD (H35.3), respectively. Specifically, the respective 2020 and 2021 ratios were averaged for the 2 years and then multiplied by the number of patients with any AMD (H35.3) determined for the year under consideration (2012–2019). This extrapolation was necessary because no differentiation in ICD-10 coding existed in Germany prior to 1 January 2020. Finally, the incidence and prevalence estimates of exudative and non-exudative AMD from the years 2012–2021 were projected to 2026 assuming a constant linear trend of total subjects with AMD (H35.3).

The annual incidence and prevalence of exudative and non-exudative AMD was reported as absolute patient numbers and proportion of the overall AOK PLUS population as well as for predefined age cohorts (< 65, 65–74, 75–84, ≥ 85 years). Furthermore, these patient numbers were used to extrapolate incidence and prevalence estimates for AMD in the SHI population in Germany as well as in the overall German population, considering differences in age and sex between the different source populations. Distributions in terms of age and sex were retrieved from publicly available statistics (for SHI: KM6 statistic on SHI membership according to the Information System of the Federal Health Monitoring [IS-GbE-Bund]; for overall Germany: Current population according to the Federal Statistical Office of Germany [Destatis]; [16, 17]).

Results

Prevalence of Exudative and Non-exudative AMD

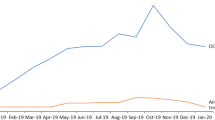

Between 2012 and 2021, the prevalence of diagnosed AMD remained relatively stable, ranging from 2.24% (minimum in 2021) to 3.03% (maximum in 2014) of the AOK PLUS population. The corresponding absolute patient counts varied between 73,524 in 2021 and 78,497 in 2014 (Supplementary Materials Table S2). To estimate the point prevalence of diagnosed non-exudative AMD for the years 2012–2019, the determined patient counts for diagnosed AMD for each year under consideration were multiplied by the averaged ratio of non-exudative AMD to AMD as determined for the years 2020 and 2021 (mean ratio H35.31/H35.3 over both years was 0.431). Equivalently, the point prevalence of exudative AMD was calculated by multiplying the patient counts for diagnosed AMD for each year under consideration (2012–2019) by the mean ratio H35.30/H35.3, which amounted to 0.236 (determined from the years 2020 and 2021). The estimated prevalence of diagnosed non-exudative AMD was about twice as high as for diagnosed exudative AMD (Table 1, Fig. 1). As for the most recent point estimate (on 31 December 2021), there were a total of 17,955 prevalent patients (0.55% of total AOK population) with exudative AMD and 31,388 prevalent patients (0.96%) with non-exudative AMD (Table 1). From the 2020 and 2021 prevalence estimates, we determined an average ratio of diagnosed exudative AMD to diagnosed non-exudative AMD of 0.55. Overlapping group assignment (H35.31 + H35.30) was observed in 7500 patients (0.23%) in 2021. Furthermore, the prevalence of diagnosed AMD was substantially higher in the elderly population (85+ years) compared with individuals < 65 years (exudative AMD: 6.90 vs 0.49%; non-exudative AMD: 11.42% vs 0.71%; Fig. 2). Moreover, both exudative and non-exudative AMDs were diagnosed more frequently in women than in men (exudative AMD: 0.66% vs 0.43%; non-exudative AMD: 1.18 vs 0.71%). After adjustment for differences in age and sex distribution between the AOK PLUS and the general SHI population as well as the total population in Germany, the respective prevalence rates slightly decreased (Table 1).

Prevalence of diagnosed non-exudative and exudative AMD in the SHI population and the population of Germany (2012–2026). The numbers for the years 2020–2021 (symbols) were observed based on the specific ICD-10 coding for exudative and non-exudative AMD; the estimates for 2012–2019 (symbols) are projections calculated as described in the methods section; the linear function was fit to the values from 2012 to 2021 to calculate the forecast for 2026. AMD age-related macular degeneration, ICD-10 International Statistical Classification of Diseases Tenth Revision, SHI statutory health insuranc

Figure 1 shows the projected (2012–2019) and observed (2020–2021) numbers of patients with exudative and non-exudative AMD and provides a forecast for patient numbers between 2022 and 2026, assuming a constant linear trend in growth. The corresponding prevalence proportions ranged from 0.43 to 0.49% for diagnosed exudative AMD and from 0.80 to 0.90% for diagnosed non-exudative AMD in the SHI population in Germany. In the overall German population, which is slightly younger than the SHI population, exudative AMD was estimated to be diagnosed in 0.39–0.47% of the individuals, whereas the prevalence of diagnosed non-exudative AMD was estimated to be 0.72–0.87%. For both exudative and non-exudative AMD, the majority of patients was > 75 years old (Fig. 2).

Incidence of Exudative and Non-exudative AMD

On average, the cumulative incidence for receiving a diagnosis of AMD amounted to 0.51% among insured persons at risk per year during the study period. For the estimation of the cumulative incidence of non-exudative AMD for the years 2012 to 2019 (Table 2), the determined patient counts for newly diagnosed AMD for each year under consideration were multiplied by the average ratio of newly diagnosed non-exudative AMD to newly diagnosed AMD as determined for the years 2020 and 2021 (mean H35.31/H35.3 over both years was 0.447). In analogy, the incidence of exudative AMD was calculated by multiplying the patient counts for newly diagnosed AMD for each year under consideration (2012–2019) by the mean ratio H35.30/H35.3 (determined from newly diagnosed cases in 2020 and 2021 and averaged over both years), which amounted to 0.187. Patients with newly diagnosed exudative AMD accounted on average (over the entire study period) for an estimated 0.09% of the insured persons at risk, whereas approximately 0.22% reflected newly diagnosed non-exudative AMD cases in the AOK PLUS population at risk on average per year (Table 2). As observed for the prevalence estimates, incident cases of exudative AMD amounted to about half of the patients with newly diagnosed non-exudative AMD (Table 2). The risk for new diagnosis of AMD was highest among patients aged 75–84 years (exudative: 1.72%, non-exudative: 3.68%) and those > 85 (exudative: 1.69%, non-exudative: 3.22%). In addition, newly diagnosed AMD (incidence) was substantially higher in women than in men of all age cohorts (exudative: 1.08% vs 0.82%, non-exudative: 2.84% vs 1.88%).

Adjusted to the age and sex distribution in SHI and the total population in Germany, the cumulative incidence of AMD corresponding to newly diagnosed AMD cases showed a slight increase over time (Fig. 3). For Germany, the mean cumulative incidence for diagnosed exudative and non-exudative AMD was estimated to be 0.07 and 0.16% over 1 year, while in the German SHI population the respective incidence estimates amounted to 0.07 and 0.17% (Table 2). In absolute terms, an average of 52,676 patients with exudative AMD and 121,509 patients with non-exudative AMD were newly diagnosed per year in the SHI-covered population; in the total population in Germany, 56,714 newly diagnosed patients with exudative AMD and 130,129 newly diagnosed patients with non-exudative AMD were estimated on average per year during the 10-year study period.

Projected 1-year cumulative incidence of non-exudative and exudative AMD (corresponding to newly diagnosed) in the SHI population and the population of Germany (2012–2026). The numbers for the years 2020–2021 (symbols) were observed based on the specific ICD-10 coding for exudative and non-exudative AMD; the estimates for 2012–2019 (symbols) are projections calculated as described in the methods section; the linear function was fit to the values from 2012 to 2021 to calculate the forecast for 2026. AMD age-related macular degeneration, ICD-10 International Statistical Classification of Diseases Tenth Revision, SHI statutory health insurance

Discussion

Using administrative claims data, we provide the most recent estimates for the distribution of diagnosed AMD stages classified into non-exudative and exudative AMD for the German health care system based on large-scale observations of > 3.3 million individuals of all ages. The number of diagnosed AMD cases increased slightly over the study period, possibly related to population aging over this period. The prevalence of diagnosed exudative AMD (0.44%) was about half as high as the prevalence of diagnosed non-exudative AMD (including early, intermediate, and atrophic late AMD, 0.77%) determined in 2021.

Recently, another claims data-based estimate of the number of patients with exudative AMD in the statutory health insurance in Germany was published [23]. Based on this claims data analysis from 16 statutory health insurances with approximately 3.5 million insured patients, the number of patients with exudative AMD in the SHI was estimated to be approximately 379.677 patients (prevalence rate 0.62%), which is very similar to the patient numbers determined in our study.

In comparison, the Gutenberg Health Study presented first epidemiologic evidence on AMD for Germany in 2014, examining 4340 study participants aged 35–74 years of which 11.9% showed signs of early AMD and 0.2% of late-stage AMD [24]. The estimate of late AMD prevalence may be lower than in the study at hand because patients aged ≥ 75 years old were excluded in the Gutenberg study. Another population study in Germany also based on fundus images included only adults aged 70+ years and reported a late AMD prevalence of 7.3% [25], which is in the range of our findings for adults aged 65+ years. For UK, Owen et al. [26] calculated a prevalence for late AMD of 2.4% (including GA [1.3%] and exudative AMD [1.2%]) based on 57,173 individuals between the ages of 50 and 97 years. Although age cohorts were defined differently than in our claims data study, the estimated prevalence of exudative AMD in the UK was similar. In contrast, the prevalence estimates determined from Japanese claims data for any stage of AMD amounted to 0.26% in 2013 [27], which is significantly lower than the estimates from our study in Germany.

A more systematic approach was provided by Rudnicka et al. [28], who summarized 25 epidemiologic studies of AMD in Europe that used fundus imaging data all published up to September 2010. Based on this meta-analysis, a pooled prevalence for late-stage AMD of 1.4% was estimated in 51,173 individuals at age 70 (including GA [0.7%] and exudative AMD [0.7%]). However, the authors had to acknowledge a considerable heterogeneity in prevalence estimates for AMD between the studies included, which was mostly associated with differences in age and study characteristics. For this reason, age-independent prevalence estimates were not presented. Because the risk for the occurrence of AMD increases approximately exponentially with age, adjustment for age-specific distributions is of paramount importance before comparing prevalence estimates. By using a similar approach, Li et al. [29] provided an updated prevalence estimate for early and intermediate AMD (25.3%) as well as late-stage AMD (2.4%; including GA and exudative AMD) in 55,323 European individuals with a narrower age range of 60 to 81 years, based on a meta-analysis of 22 population-based studies published between 1996 and 2018. The reported age-specific prevalence for exudative AMD in Germany was lower than in our results in patients aged 65 to 75 years (0.3% vs 1.6%); the pooled prevalence estimate for Europe overall was in between (0.8%).

In contrast to exudative AMD, for which anti-VEGF treatments are well established and an ICD-10 code exists in Germany, neither a treatment option nor an ICD-10 code is currently available for GA in Germany. However, the literature suggests that the prevalence estimate of exudative AMD and GA is comparable, with a ratio within the range of 0.714 to 1.083 cases diagnosed with GA per patient with exudative AMD [26, 28, 29]. Considering this, we estimated approximately 382,500 (range: 272,800–494,200) patients with GA within the German statutory health insurance population and 424,100 (range: 303,100–545,100) within the overall population in Germany [30].

Strength and Limitations

The strength of this claims data analysis is the large database which includes all ages from approximately 4% of the total SHI population in Germany, representative of its public healthcare system and of Germany as a whole. Other strengths include the longitudinal records of reliable diagnoses from ophthalmology specialists over a 10-year period.

However, it must be acknowledged that the true prevalence of non-exudative AMD was most likely underestimated in this study, as early stages of AMD often remain undiagnosed as they do not go along with visual impairment and thus may not lead to contact with an ophthalmologist. Therefore, the documented coding of AMD diagnoses may not fully reflect the prevalence of the disease but rather the prevalence of the diagnosed disease. We attempted to compensate for this potential bias by including a longer interval between two outpatient diagnoses when selecting patients with non-exudative AMD (24 months instead of 12 months as for exudative AMD). However, given the lack of available therapeutic options for non-exudative AMD, this limitation cannot be fully overcome.

Moreover, during the COVID-19 pandemic, avoidance of ophthalmologist visits, especially among an elderly and more vulnerable patient populations, may have led to further underestimation of observed newly diagnosed cases, particular in early 2020. In fact, we observed a decrease in the number of newly diagnosed cases of exudative AMD in 2020, which was offset by a higher-than-average proportion of new cases occurring in the following year.

Furthermore, it should be noted that for the time frame between 2012 and 2019, the identification of AMD relied on projections for patients with a diagnosis for ‘Degeneration of macula and posterior pole’ (ICD-10 H35.3) because more detailed coding became available only in 2020. To overcome this obstacle, incidence and prevalence estimates from 2012 to 2019 were based on the ratios of exudative AMD (H35.30) to any macular degeneration (H35.3) and on non-exudative AMD (H35.31) to any macular degeneration (H35.3), respectively, observed in 2020 and 2021. It was assumed that these proportions remained constant during the entire study period. Using this strategy allowed us to exclude potential contributions of patients with unspecified or other degeneration of the macula and posterior pole, as coded by ICD-10 H35.38 or H35.39.

The definition of incident cases of exudative AMD for the years 2020 and 2021 is limited by the fact that no H35.3 diagnosis is allowed in the calendar year before the year of first exudative AMD diagnosis, which would mean that patients with previously diagnosed early or intermediate stages of AMD were excluded. However, as the proportion of diagnoses for these mostly asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic stages of AMD are considered low, a large error in the estimates of exudative AMD incidence is not anticipated. Additionally, the prevalence of diagnosed AMD in Germany may also be underestimated in this study because of a lower availability of ophthalmic practices in the regions of Saxony and Thuringia compared to Germany as a whole. Adjustment for regional components of care and patient characteristics other than age and sex was not possible. Interestingly, although the first anti-VEGF therapy was approved in 2007 (Lucentis, INN-ranibizumab), it took 7 more years until guidelines and recommendations for diagnosis and management of exudative AMD were developed by European retina specialists in 2014 [31], although the first recommendations were published in Germany in 2009 [32, 33]. This indicates on the one hand that enhancing disease awareness for AMD (including guidance for diagnosis) is an ongoing process; on the other hand, it also shows that once treatment options are available diagnosis and disease management can be improved. In contrast to exudative AMD, no medicinal product is currently approved for the treatment of patients with non-exudative AMD in Europe. Especially for GA, as the advanced form of non-exudative AMD, a recent Delphi panel showed that consensus publications outlining practices in diagnosis and current management of GA are missing [34]. The above indicates that the determined number of non-exudative AMD cases might be underestimated because of the lacking possibility of treatment. Nonetheless, in 2015, angiography via optical coherence tomography (OCT) became commercially available, allowing for improved non-invasive imaging of the retina and choroid [35]. Therefore, within the last years, OCT gained more importance for diagnosis and monitoring in the field of AMD [36]. In the present study, despite the existing challenges in diagnosing exudative and non-exudative AMD, this could have contributed to a more accurate detection of AMD and consequently to the detected increase of AMD cases within the last years.

Due to the lack of specific ICD codes, the number of patients with diagnosed non-exudative AMD estimated here includes patients with AMD of all stages (early, intermediate and GA). The proportion of patients with GA in Germany could not be determined within this study. To date, the proportion of patients with GA can only be extrapolated from the proportion of diagnosed exudative AMD. These estimates assume that the ratios between GA and exudative AMD known from previous meta-analyses [25, 27, 28, 30] have not changed over time and are largely homogeneous in Europe.

Conclusion

We provide up-to-date estimates for prevalence and incidence of diagnosed non-exudative and exudative AMD in Germany. The number of diagnosed cases with AMD in Germany has increased only slightly over the past decade. A ratio of the prevalence of non-exudative AMD to exudative AMD of approximately 2:1 was determined for the years 2020 and 2021. However, the true prevalence of non-exudative AMD is likely underestimated in this observational study because a treatment is not yet available for these patients and earlier stages associated with hardly any visual impairment often remain undiagnosed. As more diagnostic coding data for AMD stages become available, the estimates presented here should be revisited.

Data Availability

All data relevant to this study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary material. The source data that support the findings of this study are available from AOK PLUS, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and so are not publicly available.

References

Claessen H, Kvitkina T, Narres M, Trautner C, Bertram B, Icks A. Markedly decreasing incidence of cause-specific blindness in Saxony (Eastern Germany). Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2021;259(5):1089–101.

Mauschitz M, Li J, Larsen P, Köberlein-Neu J, Holz F, Breteler M, et al. Epidemiology of severe visual impairment and blindness of old people in Germany. Der Ophthalmologe. 2019;116:201–12.

Taylor HR, Keeffe JE. World blindness: a 21st century perspective. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85(3):261–6.

Wong WL, Su X, Li X, Cheung CM, Klein R, Cheng CY, et al. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(2):e106-16.

Khan JC, Thurlby DA, Shahid H, Clayton DG, Yates JR, Bradley M, et al. Smoking and age related macular degeneration: the number of pack years of cigarette smoking is a major determinant of risk for both geographic atrophy and choroidal neovascularisation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(1):75–80.

Pugazhendhi A, Hubbell M, Jairam P, Ambati B. Neovascular macular degeneration: a review of etiology, risk factors, and recent advances in research and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(3):1170.

Ambati J, Fowler BJ. Mechanisms of age-related macular degeneration. Neuron. 2012;75(1):26–39.

EyeWiki. Age-Related Macular Degeneration.

Ophthalmology Do. AMD Treatment Guidelines Harvard Medical School [Available from: https://eye.hms.harvard.edu/eyeinsights/2015-january/age-related-macular-degeneration-amd. Accessed 14 Jan 2022.

Chew EY, Clemons TE, Agrón E, Sperduto RD, SanGiovanni JP, Davis MD, et al. Ten-year follow-up of age-related macular degeneration in the age-related eye disease study: AREDS report no. 36. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(3):272–7.

Keenan TD, Agrón E, Domalpally A, Clemons TE, van Asten F, Wong WT, et al. Progression of geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration: AREDS2 report number 16. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(12):1913–28.

Fleckenstein M, Mitchell P, Freund KB, Sadda S, Holz FG, Brittain C, et al. The progression of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(3):369–90.

Danis RP, Lavine JA, Domalpally A. Geographic atrophy in patients with advanced dry age-related macular degeneration: current challenges and future prospects. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:2159–74.

FDA Approves SYFOVRE™ (pegcetacoplan injection) as the First and Only Treatment for Geographic Atrophy (GA), a Leading Cause of Blindness [press release]. 2023. https://investors.apellis.com/news-releases/news-release-details/fda-approves-syfovretm-pegcetacoplan-injection-first-and-only.

Iveric Bio Receives U.S. FDA Approval for IZERVAY™ (avacincaptad pegol intravitreal solution), a New Treatment for Geographic Atrophy [press release]. 2023. https://www.astellas.com/en/news/28281.

Bundes Gd. Mitglieder und mitversicherte Familienangehörige der gesetzlichen Krankenversicherung am 1.7. eines Jahres (Anzahl). Gliederungsmerkmale: Jahre, Deutschland, Alter, Geschlecht, Kassenart, Versichertengruppe. [Available from: https://www.gbe-bund.de/gbe/pkg_isgbe5.prc_menu_olap?p_uid=gast&p_aid=7373405&p_sprache=D&p_help=0&p_indnr=249&p_indsp=&p_ityp=H&p_fid. Accessed 14 Jun 2023.

Statistisches Bundesamt D. Bevölkerungsstand [Available from: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Bevoelkerungsvorausberechnung/_inhalt.html. Accessed 14 Jun 2023.

Datzmann T, Schmitt J, Fuhrmann S, Roessler M, Meier F, Schoffer O. Implementation and effectiveness of novel therapeutic substances for advanced malignant melanoma in Saxony, Germany, 2010–2020-cohort study based on administrative data. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(24):6150.

Flemming R. Patterns of pregabalin prescribing in four German federal states: analysis of routine data to investigate potential misuse of pregabalin. BMJ Open. 2022;12(7): e060104.

Markevych I, Tesch F, Datzmann T, Romanos M, Schmitt J, Heinrich J. Outdoor air pollution, greenspace, and incidence of ADHD: A semi-individual study. Sci Total Environ. 2018;642:1362–8.

Trautmann F, Schuler M, Schmitt J. Burden of soft-tissue and bone sarcoma in routine care: Estimation of incidence, prevalence and survival for health services research. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39(3):440–6.

Epping J, Stahmeyer JT, Tetzlaff F, Tetzlaff J. M2Q or Something else? The Impact of Varying Case Selection Criteria on the Prevalence Estimation of Chronic Diseases Based on Outpatient Diagnoses in German Claims Data. Gesundheitswesen (Bundesverband der Arzte des Offentlichen Gesundheitsdienstes (Germany)). 2023. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-2052-6477

IQWiG. Faricimab (neovaskuläre altersabhängige Makuladegeneration)—Nutzenbewertung gemäß § 35a SGB V. In: Institut_für_Qualität_und_Wirtschaftlichkeit_im_Gesundheitswesen, editor. 2023. https://www.iqwig.de/download/a22-110_faricimab_nutzenbewertung-35a-sgb-v_v1-0.pdf.

Korb CA, Kottler UB, Wolfram C, Hoehn R, Schulz A, Zwiener I, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in a large European cohort: results from the population-based Gutenberg Health Study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;252(9):1403–11.

Brandl C, Zimmermann ME, Günther F, Barth T, Olden M, Schelter SC, et al. On the impact of different approaches to classify age-related macular degeneration: results from the German AugUR study. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):8675.

Owen CG, Jarrar Z, Wormald R, Cook DG, Fletcher AE, Rudnicka AR. The estimated prevalence and incidence of late stage age related macular degeneration in the UK. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(5):752–6.

Kume A, Ohshiro T, Sakurada Y, Kikushima W, Yoneyama S, Kashiwagi K. Treatment patterns and health care costs for age-related macular degeneration in Japan: an analysis of national insurance claims data. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(6):1263–8.

Rudnicka AR, Jarrar Z, Wormald R, Cook DG, Fletcher A, Owen CG. Age and gender variations in age-related macular degeneration prevalence in populations of European ancestry: a meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(3):571–80.

Li JQ, Welchowski T, Schmid M, Mauschitz MM, Holz FG, Finger RP. Prevalence and incidence of age-related macular degeneration in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104(8):1077–84.

Bubendorfer-Vorwerk H, Schuster A, Lewis P, Picker N, Finger R, editors. Prevalence of geographic atrophy in Germany—an assessment derived from literature-based estimates and claims data results. 35th International Congress of German Ophthalmic Surgery (DOC); 2023 June 15–17th 2023; Nürnberg.

Schmidt-Erfurth U, Chong V, Loewenstein A, Larsen M, Souied E, Schlingemann R, et al. Guidelines for the management of neovascular age-related macular degeneration by the European Society of Retina Specialists (EURETINA). Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98(9):1144–67.

Bartz-Schmidt U, Bertram B, Bornfeld N, Grisanti S, Holz F, Lemmen K, et al. Stellungnahme der retinologischen gesellschaft, der Deutschen ophthalmologischen gesellschaft und des berufsverbands der augenärzte Deutschlands zu aktuellen therapeutischen möglichkeiten bei der neovaskulären altersabhängigen makuladegeneration: Stand Juni 2007. Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde. 2007;224(7):559–66.

der Retinologischen AS, Deutschlands VA. Neue Aspekte in der Therapie der neovaskulären altersabhängigen Makuladegeneration. Ophthalmologe. 2009;106:457–64.

Singh RP, Amoaku W, Bandello F, Chen FK, Holz FG, Kodjikian L, et al. Diagnosis and management of patients with geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration: a delphi consensus exercise. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2023;54(10):589–98.

Annie S. OCT-A: A Path to Earlier Diagnosis of Dry AMD. EyeNet Magazine. 2018. https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/a-path-to-earlier-diagnosis-of-dry-amd

Stahl A. The diagnosis and treatment of age-related macular degeneration. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117(29–30):513–20.

Acknowledgements

Medical Writing, Editorial and Other Assistance.

Editorial support was provided by Joseph Alling of OPEN Health Communications and funded by Apellis Pharmaceuticals.

Authorship.

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Funding

Sponsorship for this study the journal’s Rapid Service Fee were funded by Apellis Germany GmbH (Munich, Germany). The sponsor participated in the design of the study; interpretation of the data; and preparation, review and approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Alexander K. Schuster, Lilia Leisle, Nils Picker, Philipp Hahn, Jürgen Wasem, and Philip Lewis contributed to the study design; Philipp Hahn was responsible for the acquisition of study data; Lilia Leisle and Nils Picker analyzed the study data; Alexander K. Schuster, Lilia Leisle, Nils Picker, Hanne Bubendorfer-Vorwerk, Philip Lewis, Jürgen Wasem, and Robert P. Finger interpreted the study data; all authors critically reviewed the manuscript and provided final approval.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE disclosures forms. Alexander K. Schuster, Robert P. Finger and Jürgen Wasem received consultancy fees for results publication and advice on real-world evidence generation from Apellis Germany GmbH. Alexander K. Schuster also received consultancy fees from Abbvie for advice on real-world evidence generation and he received research funding from Heidelberg Engineering, Bayer, Santen and Novartis. Philipp Hahn participated in this study as a staff member of IPAM; Nils Picker and Lilia Leisle participated in this study as staff members of Cytel; the work of IPAM and Cytel in this study was funded by Apellis Germany GmbH. Philip Lewis and Hanne Bubendorfer-Vorwerk are employees of Apellis Germany GmbH. Robert P. Finger changed affiliations during the study from the Department of Ophthalmology, University Hospital Bonn, Bonn, Germany, to the Department of Ophthalmology, University Hospital Mannheim GmbH, Mannheim, Germany.

Ethical Approval

Research and analysis were conducted on anonymized data provided by AOK PLUS under formal agreement, and in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. No research was conducted on human subjects. In accordance with German laws (§ 75 of Book 10 of the German Code of Social Law [SGB X]), the use of such data is not subject to ethics committee approval, because conclusions about individual patients are excluded and only aggregated results are presented. No patient authorization was required because solely deidentified data were analyzed.

Additional information

Prior Presentation: Parts of this study have been presented at the 35th International Congress of German Ophthalmic Surgery (DOC; Nürenberg, Germany, 15–17 June 2023).

R.P. Finger’s affiliation has changed since the time of this study.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schuster, A.K., Leisle, L., Picker, N. et al. Epidemiology of Diagnosed Age-related Macular Degeneration in Germany: An Evaluation of the Prevalence Using AOK PLUS Claims Data. Ophthalmol Ther 13, 1025–1039 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40123-024-00901-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40123-024-00901-6