Abstract

Introduction

Food insecurity is a well-established predictor of poor health outcomes. Antiretroviral therapies (ARTs) that should be taken with food to increase bioavailability may further challenge food insecure patients. This study examined factors associated with antiretroviral adherence and HIV viral suppression among people living with HIV who are food insecure and prescribed medications that require food.

Methods

A community sample of 313 men and 105 women who experienced food insecurity in the previous month and were currently taking ART completed computerized interviews, urine screening for drug use, prospective biweekly unannounced pill count adherence assessments, and obtained their HIV viral load and CD4 cell counts from medical records.

Results

Individuals taking ART regimens that should be taken with food were significantly more likely to be unemployed, were living longer with an HIV diagnosis, had lower CD4 cell counts, poorer HIV suppression, and endorsed more beliefs that taking medications was necessary for their health. Multivariable regression models controlling for potential confounding factors showed that receiving ART that requires food was significantly related to poorer ART adherence and unsuppressed HIV in this food insecure sample.

Conclusion

People living with HIV who are food insecure likely experience multiple facets of poverty that challenge their medication adherence, but food insecurity is the only such factor that is directly related to the pharmacokinetics of some antiretroviral medications. Achieving optimal treatment outcomes for HIV infection will require routine assessment of access to food when determining patient-tailored ART regimens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Food insecurity is a significant barrier to long-term antiretroviral therapy (ART) in resource-rich as well as resource-limited settings [1–3]. In urban centers with abundant but inequitable access to food, including in the United States (US) and Canada, people living with HIV who experience food insecurity are less likely to be adherent to treatment, achieve poorer HIV viral suppression, and have greater mortality than their food secure counterparts [4–7]. Food insecurity itself can interfere with medication adherence by disrupting daily routines, impairing memory and attention, impeding adherence strategies, and reducing motivation [8]. In essence, the immediacy of accessing food to meet survival needs can understandably take priority over adhering to medication schedules. Patients may forego taking medications at times when food is unavailable if they have been instructed that their medicines should always be taken with food. In addition to the direct effects of food insecurity on antiretroviral adherence, lacking food will further challenge the clinical efficacy of ART when required to be taken with food for maximum absorption and clinical benefit [9].

Food is required for processing, absorption, and optimal clinical benefits for certain ART regimens, with pharmacokinetic studies showing as much as a 38% increase in the availability of some antiretrovirals when taken with food [10, 11]. The protease inhibitor darunavir, for example, is rapidly absorbed and systemic exposure is increased by 30% when taken with a meal [12, 13]. Similarly, administration of atazanavir with a light meal results in a 70% increase in drug plasma concentration [14]. The bioavailability of ritonavir, which itself is used to boost the bioavailability of other protease inhibitors, is also suboptimal when taken without food [15]. Similarly, taking tenofovir and rilpivirine with a meal can mean as much as a 36% increase in drug bioavailability [16, 17]. People who are food insecure must therefore periodically choose to either take their medications knowing they are not following directed use or miss their medications altogether when food is unavailable. People living with HIV who experience food insecurity may therefore have poorer clinical outcomes as a result of both non-adherence and insufficient absorption. In a previous study, we found that a significant number of people living with HIV who are food insecure are prescribed ART that should be taken with food and these individuals had more HIV symptoms, lower CD4 cell counts, and poorer HIV suppression than their counterparts who were not prescribed ART that requires food [18]. Given that our previous study was the first to investigate antiretrovirals that require food prescribed to people with HIV who are also food insecure, the current study sought to extend those findings in an independent sample.

The current study investigated ART adherence and viral suppression among people living with HIV who are food insecure in relation to receiving ART that should be taken with food. We extend past research that has examined food insecurity in relation to ART adherence by focusing on ART regimens that require food. In addition, the current study incudes potential confounding factors that may account for the previously observed associations between non-adherence and medication requirements including side effects and medication adherence motivational beliefs. We hypothesized that ART adherence and HIV viral suppression would be poorer among people living with HIV who are food insecure and are prescribed antiretroviral regimens that require food compared to individuals who are food insecure and prescribed ART regimens that do not require food.

Methods

Participants

Participants were men and women taking antiretrovirals to treat their HIV infection and had experienced food insecurity in the previous month. The site of the study was Atlanta, Georgia with an annual incidence of 30.3 per 100,000, exceeding the 19.6 per 100,000 population rate of HIV in major US cities. Eligible participants were aged 18 years or older, HIV positive, and currently taking ART.

Procedures

The study was conducted between January 2013 and March 2014. A total of 1,101 people living with HIV were recruited through targeted community sampling with both venue recruitment and snowball sampling techniques. Venue recruitment relied on responses to brochures placed in waiting rooms of HIV service providers and infectious disease clinics throughout Atlanta, GA. Participants were also encouraged to use the project brochures to refer their HIV-positive friends to the study. Individuals provided informed consent prior to completing any study activities.

Participants completed four sources of data: audio computer-assisted self-interviews (ACASI) to assess demographic and behavioral characteristics at the start of the study [19, 20]; HIV RNA (viral load) and CD4 cell counts obtained from medical records; a urine specimen for drug screening; and unannounced pill counts to prospectively assess ART regimens and adherence. The specific measures are described below. The University of Connecticut Institutional Review Board approved all procedures.

Measures

Computerized Interviews

Participants were asked their gender, age, years of education, income, ethnicity, and employment status. We also collected the year that participants first tested HIV positive, a measure of 14 HIV-related symptoms of 2-weeks duration (indicated as having or not having experienced each symptom, summed to a composite score) [21], and experience of 11 common ART side effects (ranged between 0 = “not experiencing” to 3 = “severely experiencing”, summed to composite score) [22]. To assess alcohol use, we administered the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), a 10-item scale designed to measure alcohol consumption and identify risks for alcohol abuse and dependence [23]. Scores on the AUDIT range from 0–40 and the AUDIT has demonstrated acceptable reliability and validity [24]. The first item on the AUDIT was used to index frequency of alcohol use over the previous week.

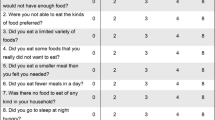

To assess food insecurity, we used items adapted from the US Food Security Scale that have been validated in past research and used by the US Census Bureau [25]. The specific items are reported in the results section. We also included an item asking participants if they had to decide whether to buy food or medications. Food insecurity indicators were collected with respect to experiences in the past month, dichotomized (experienced/not experienced), and summed to create a food insecurity index.

We used the Beliefs about Medicine Questionnaire to assess participant’s motivations for adhering to medications [26, 27]. The medication necessity scale consists of five items reflecting the perceived benefits of medications in direct relation to health; example items include “My health, at present, depends on my medicine”, “My life would be impossible without my medicine”, and “My medicines protect me from becoming worse”. The five-item medication concerns scale reflects the potential adverse effects and costs of medication; example items include “Having to take my medicines worries me”, “My medicines disrupt my life”, and “I sometimes worry about the long-term effects of my medicines”. Items are responded to on a 5-point scale, 1 = “strongly agree”, 5 = “strongly disagree”. The medication necessity and concerns scales were both internally consistent, alphas = 0.78 and 0.81, respectively.

Urine Screening for Drug Use

To objectively screen for illicit drug use, we conducted a multi-panel urine dip test to detect common illicit drug use. This test strip uses a lateral flow chromatographic immunoassay for qualitative detection of 12 drugs and drug metabolites. These tests are Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved and are reliable and valid for initial drug screening (Reditest®-12; Redwood Toxicology Laboratory, Santa Rosa, CA, USA).

Chart Abstracted HIV Viral Load and CD4 Cell Counts

We used a participant-assisted method for collecting chart abstracted HIV viral load and CD4 cell counts from participants’ medical records. Participants were given a form that asks their physician’s office to provide the results of their most recent HIV viral load and CD4 cell counts and dates (not older than 3 months). These data were therefore obtained directly by the participants from their health care providers. The form included a place for the provider’s office stamp or signature to assure data authenticity. HIV RNA below detection was defined as less than 200 copies/mL for uniformity across providers.

ART Regimen Determination and Adherence

Participants consented to three unannounced telephone-based pill counts that occurred over a 6-week period. Unannounced pill counts are reliable and valid in assessing medication adherence when conducted in homes [28] and on cell phones [29, 30]. In this study, we conducted unannounced cell-phone-based pill counts. Participants were provided with a free cell phone for use in the study assessments. An office-based interview included a full accounting and recording of all prescription medications, determining ART regimen, and systematic training in the pill counting procedure. Participants were subsequently called at three unscheduled times over 12- to 16-day intervals. Pharmacy information from pill bottles was also collected to verify the number of pills dispensed between calls. Adherence was defined as the ratio of pills counted relative to pills prescribed, taking into account the number of pills dispensed. ART adherence was examined as a continuous variable and as a clinically defined categorical variable with adherence defined as greater than 85% of their medications [3, 4].

Data Analyses

Of the 1,101 individuals recruited, 498 screened positive for experiencing at least one indicator of food insecurity (see below for exact items). Among these participants, 481 (96%) returned with their medical chart abstracted viral loads and 418 (84%) completed unannounced pill counts for ART adherence. All participants with adherence data also had returned with their viral loads. Therefore, analyses were performed on the 418 food insecure persons with adherence data. Setting P < 0.05 significance for an odds ratio of 1 standard deviation increase in exposure and odds ratio of 1.5 for one standard deviation increase in a covariate with a sample size of 418, calculations estimate statistical power of 0.89, indicating sufficient power for our statistical models [31, 32].

Participants were grouped on the basis of the food requirements of their ART regimen. We obtained recommended ART administration instructions from antiretroviral treatment guidelines for adults [33] and recommendations from AIDSmeds [34]. Five protease inhibitors and one non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) were recommended for administration with food; 195 participants were taking ART that did not require food and 223 participants were taking ART that requires food. Descriptive analyses compared participants who were taking ART that did not require food with those who were taking ART that did require food. Comparisons used contingency table Chi-square tests for categorical variables and independent t tests for continuous measures. To test the main study hypothesis that participants who are prescribed ART that requires food would have poorer ART adherence and poorer viral suppression, we performed separate multivariable logistic regressions for each outcome, reporting odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. The regression models controlled for factors that are known to predict adherence (i.e., substance use) and variables found related to ART regimens that require food in the descriptive analyses. All variables were continuous scaled except employment (coded 0 = unemployed, 1 = employed), income (0 = <$10,000/year, 1 = ≥ $10,000/year), drug use (0 = none detected, 1 = detected), and ART regimen requiring food (0 = does not require food, 1 = requires food). All analyses were conducted in SPSS Statistics (version 20; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Of the 418 individuals who had experienced food insecurity in the previous month, 223 (53%) were prescribed ART that should be taken with food. The majority of participants were receiving regimens that included nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI) and protease inhibitors, the two largest classes of medications. Overall, ART adherence averaged 81% of medications taken over the subsequent month, with considerable variability in adherence across classes of medications (see Table 1). Results showed that most indicators of food insecurity were evenly distributed among people who were not and were prescribed ART that requires food. However, having had to choose between paying for food or obtaining medications occurred significantly more often for individuals prescribed ART that should be taken with food (see Table 2).

Factors Associated with Receiving ART that Requires Food

Table 3 shows the characteristics of participants taking ART that does not and does require food. Descriptive analyses found that individuals taking ART that requires food were significantly more likely unemployed, had lower CD4 cell counts, were more likely to have unsuppressed HIV viral loads, were living with HIV diagnoses longer, and reported significantly more beliefs that their medications are necessary for their health. There were no other differences between individuals taking ART that requires food verses those not taking medications that require food.

Predictors of ART Adherence

We constructed a multivariable logistic regression model to test the independent effects of ART regimens requiring food on medication adherence over the prospective 1-month period. The model included factors that were associated with taking ART regimens that require food including employment, years living with HIV diagnosis, and adherence motivation beliefs. In addition, the model included socio-demographic and behavioral factors that are generally known to be associated with adherence including education, income, substance use, and medication side effects. Results showed that greater alcohol use, fewer beliefs that medications are necessary, and being prescribed an ART regimen that requires food significantly predicted poorer ART adherence over and above the other factors included in the model (see Table 4).

Predictors of HIV Suppression

A second multivariable logistic regression model tested the independent effects of ART regimens requiring food on chart abstracted HIV viral load. The model included all of the factors described above for the adherence model. Table 5 shows that participant unemployment, greater beliefs about concerns over medications, and being prescribed an ART regimen that requires food significantly predicted having unsuppressed (detectable) HIV viral load, over and above the other factors included in the model.

Discussion

In recently published Antiretroviral Treatment of Adult HIV Infection Recommendations, the International AIDS Society (IAS) reviewed the many benefits of HIV treatment and provided guidelines for achieving optimal clinical outcomes [35]. Recommendations are focused on settings where ARTs are available, particularly resource-rich countries. Guidance for ART takes into consideration multiple patient and regimen characteristics including efficacy, toxicity, pill burden, dosing, viral resistance, comorbid conditions, and cost. However, a significant omission from consideration in selecting an ART regimen is the patient’s access to sufficient and reliable food sources. In the current study of people living with HIV who experience food insecurity, we found that more than half were prescribed ART that should be taken with food. The prevalence of multiple indicators of food insecurity was evenly distributed among individuals who were prescribed ART that does and does not require food, including more than one-third experiencing hunger in the previous month. However, the one factor that was associated with taking ART that requires food was having had to choose between obtaining medications and paying for food in the previous month. This finding speaks to the complexity of managing scarce resources in meeting the demands of medications that must be taken with food among people who are food insecure. Unlike other challenges to ART adherence among the poor, the dilemma posed by medications with food requirements is resolvable by either prescribing an ART regimen that does not require food, when appropriate and feasible, or assuring that patients are provided food to be taken with their medication.

In many cases, providers will have fewer medication options for patients who have a history of poor adherence and those patients who have been treated longer with ART. These clinical realities may explain the patterns of results in this study. Patients who are food insecure also demonstrate poorer adherence and may therefore develop resistance, leaving fewer treatment options. In addition, not all ART regimens are equally accessible through various drug assistance programs. Thus, even when providers are aware of the conflict between food insecurity and prescribing ART that requires food, their best treatment option may be a regimen that requires food for optimal absorption. In addition, programs that provide nutritional support and meals to patients are scarce in many settings. Again, even when providers are aware of patient food insecurity there are limits to their ability to provide food. These clinical realities, therefore, present clinical dilemmas that can only be resolved with access to more affordable treatment options and increased meal services for patients in need.

These findings should be interpreted in light of the study limitations. First, we relied on a convenient sample that cannot be considered representative of people living with HIV infection. The sample also came from a wide range of providers that likely varied in health services and prescription practices. While we had objective measures of ART regimens, adherence, current substance use, and clinical health status (CD4 count and viral load), our study relied on self-report instruments to assess social and behavioral characteristics, including food insecurity. Although we used reliable and valid measures, self-report data may still be subject to social response biases. In addition, we grouped all medications that require food into one class despite the variable importance of food for the absorption of any single medication. Our data also do not allow precise measurement of whether missed medication doses occurred in relation to times when food was scarce, particularly whether medications that are instructed to be taken with food are missed at those times. Future research may use event/dose level medication monitoring with time-linked measures of food intake to determine more precise associations. With these limitations in mind, we believe that our findings have implications for treatment guidelines, clinical practice and future research.

Conclusion

Given that HIV is embedded in a context of poverty, access to food should be formally assessed and explicitly considered when prescribing ART. Patients should not be expected to overcome the shame and stigma of not having food to initiate this conversation. In addition to the obvious necessity of nutrition in health, access to food is known to improve adherence [36–38]. The importance of food in health takes on a new dimension when the bioavailability of medications depends on food. Treatment guidelines cannot address every issue facing providers and patients in selecting treatment regimens. However, requiring food for optimal absorption is the only aspect of poverty directly related to the pharmacokinetics of ART. Failing to address adequate access to food when selecting ART regimens will undermine the clinical care of a significant and growing population of HIV infection patients living in poverty.

References

Anema A, Zhang W, Wu Y, et al. Availability of nutritional support services in HIV care and treatment sites in sub-Saharan African countries. Pub Health Nutr. 2012;15:938–47.

Weiser SD, Tsai AC, Gupta R, et al. Food insecurity is associated with morbidity and patterns of healthcare utilization among HIV-infected individuals in a resource-poor setting. AIDS. 2012;26:67–75.

Weiser SD, Bangsberg DR, Kegeles S, Ragland K, Kushel MB, Frongillo EA. Food insecurity among homeless and marginally housed individuals living with HIV/AIDS in San Francisco. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:841–8.

Weiser SD, Hatcher A, Frongillo EA, et al. Food insecurity is associated with greater acute care utilization among HIV-infected homeless and marginally housed individuals in San Francisco. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:91–8.

Vogenthaler NS, Kushel MB, Hadley C, et al. Food insecurity and risky sexual behaviors among homeless and marginally housed HIV-infected individuals in San Francisco. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:1688–93.

Kalichman SC, Cherry C, Amaral C, et al. Health and treatment implications of food insufficiency among people living with HIV/AIDS, Atlanta, Georgia. J Urban Health. 2010;87:631–41.

Weiser SD, Fernandes KA, Brandson EK, et al. The association between food insecurity and mortality among HIV-infected individuals on HAART. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52:342–9.

Singer AW, Weiser SD, McCoy SI. Does food insecurity undermine adherence to antiretroviral therapy? A systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2014 (Epub ahead of print).

Piacenti FJ. An update and review of antiretroviral therapy. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:1111–33.

Custodio JM, Yin X, Hepner M, et al. Effect of food on rilpivirine/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, an antiretroviral single-tablet regimen for the treatment of HIV infection. J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;54:378–85.

Lesho EP, Gey DC. Managing issues related to antiretroviral therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:675–86.

McKeage K, Perry CM, Keam SJ. Darunavir: a review of its use in the management of HIV infection in adults. Drugs. 2009;69:477–503.

Rittweger M, Arasteh K. Clinical pharmacokinetics of darunavir. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2007;46:739–56.

Le Tiec C, Barrail A, Goujard C, Taburet AM. Clinical pharmacokinetics and summary of efficacy and tolerability of atazanavir. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44:1035–50.

Klein CE, Chiu YL, Awni W, et al. The tablet formulation of lopinavir/ritonavir provides similar bioavailability to the soft-gelatin capsule formulation with less pharmacokinetic variability and diminished food effect. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:401–10.

Lu C, Jia Y, Chen L, et al. Pharmacokinetics and food interaction of a novel prodrug of tenofovir, tenofovir dipivoxil fumarate, in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2013;38:136–40.

Crauwels HM, van Heeswijk RP, Buelens A, Stevens M, Boven K, Hoetelmans RM. Impact of food and different meal types on the pharmacokinetics of rilpivirine. J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;53:834–40.

Kalichman SC, Washington C, Grebler T, et al. treatment outcomes among people living with HIV Who are food insecure and prescribed antiretrovirals taken with food. J Primary Care Commun Health. 2015;6:35–40.

Gribble JN, Miller HG, Cooley PC, Catania JA, Pollack L, Turner CF. The impact of T-ACASI interviewing on reported drug use among men who have sex with men. Subst Use Misuse. 2000;35:869–90.

Morrison-Beedy D, Carey MP, Tu X. Accuracy of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) and self-administered questionnaires for the assessment of sexual behavior. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:541–52.

Kalichman S, Rompa D, Cage M. Reliability and validity of self-reported CD4 lymphocyte count and viral load test results in people living with HIV/AIDS. Int J STD AIDS. 2000;11:579–85.

Carrieri MP, Villes V, Raffi F, et al. Self-reported side-effects of anti-retroviral treatment among IDUs: a 7-year longitudinal study (APROCO-COPILOTE COHORT ANRS CO-8). Intern J Drug Policy. 2007;18:288–95.

Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, DeLaFuente JR, Grant M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption II. Addictions. 1993;88:791–804.

Maisto SA, Conigliaro J, McNeil M, Kraemer K, Kelley ME. An empirical investigation of the factor structure of the AUDIT. Psychol Assess. 2000;12:346–53.

Cook JT, Frank DA. Food security, poverty, and human development in the United States. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1136:193–209.

Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555–67.

Horne R, Cooper V, Gellaitry G, Date HL, Fisher M. Patients’ perceptions of highly active antiretroviral therapy in relation to treatment uptake and adherence: the utility of the necessity-concerns framework. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45:334–41.

Bangsberg DR, Hecht FM, Charlebois ED, Chesney M, Moss A. Comparing objective measures of adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy: electronic medication monitors and unannounced pill counts. AIDS Behav. 2001;5:275–81.

Kalichman SC, Amaral CM, Cherry C, et al. Monitoring antiretroviral adherence by unannounced pill counts conducted by telephone: reliability and criterion-related validity. HIV Clin Trials. 2008;9:298–308.

Kalichman SC, Amaral CM, Stearns HL, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy assessed by unannounced pill counts conducted by telephone. J Gen Internal Med. 2007;22:1003–6.

Tosteson TD, Buzas JS, Demidenko E, Karagas M. Power and sample size calculations for generalized regression models with covariate measurement error. Stat Med. 2003;22:1069–82.

Biostat. Power calculations for logistic regression with exposure measurement error. 2014. Available from: http://biostat.hitchcock.org/MeasurementError/Analytics/PowerCalculationsforLogisticRegression.asp. Accessed December 24, 2014.

AIDSinfo. Clinical guidelines. NIH; 2014. Available from: http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines. Accessed December 22, 2014.

AIDSMeds. Treatments for HIV and AIDS. 2014. Available from: http://www.aidsmeds.com/list.shtml. Accessed December 22, 2014.

Gunthard HF, Aberg JA, Eron JJ, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2014 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2014;312:410–25.

Nyamathi A, Sinha S, Ganguly KK, Ramakrishna P, Suresh P, Carpenter CL. Impact of protein supplementation and care and support on body composition and CD4 count among HIV-infected women living in rural India: results from a randomized pilot clinical trial. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:2011–21.

Martinez H, Palar K, Linnemayr S, et al. Tailored nutrition education and food assistance improve adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy: evidence from Honduras. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(Suppl 5):566–77.

de Pee S, Grede N, Mehra D, Bloem MW. The enabling effect of food assistance in improving adherence and/or treatment completion for antiretroviral therapy and tuberculosis treatment: a literature review. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(Suppl 5):531–41.

Acknowledgments

This project and the article processing charges were supported by National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R01-AA021471 and the National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant R01- R01-DA033067. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Conflict of interest

Seth C. Kalichman, Christopher Washington, Tamar Grebler, Ginger Hoyt, Brandi Welles, Christopher Kegler, Moira O. Kalichman, and Chauncey Cherry declare no conflict of interest.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

Individuals provided informed consent prior to completing any study activities. The University of Connecticut Institutional Review Board approved all procedures.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kalichman, S.C., Washington, C., Grebler, T. et al. Medication Adherence and Health Outcomes of People Living with HIV Who Are Food Insecure and Prescribed Antiretrovirals That Should Be Taken with Food. Infect Dis Ther 4, 79–91 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-015-0057-y

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-015-0057-y