Abstract

Introduction

The efficacy and safety of galcanezumab as a preventive treatment in Japanese patients with episodic migraine was demonstrated in a phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (conducted December 2016–January 2019). This post hoc analysis assessed the consistency of galcanezumab efficacy through the monthly dosing interval.

Methods

Patients with 4–14 migraine headache days/month were randomized (2:1:1, stratified by baseline migraine frequency) to subcutaneous placebo (n = 230), 120-mg galcanezumab (with 240-mg loading dose; n = 115) or 240-mg galcanezumab (n = 114) once monthly for 6 months. Outcomes included change from baseline in weekly migraine headache days, proportion of patients with migraine headache on each day, and proportion of patients with worsening migraine headache days during each month ([average of weeks 3–4] − [average of weeks 1–2] > 0).

Results

In the 120-mg (approved dose) galcanezumab group, mean change from baseline in weekly migraine headache days was consistent and significantly greater (p < 0.05) than placebo for weeks 1–4; efficacy was consistent when averaged across months 1–6 and in most individual months. Averaged across months 1–6, the proportion of patients with migraine headache was significantly lower with galcanezumab than placebo on every day in both dose groups and was not significantly different between days 2 and 28 with 120-mg galcanezumab (p = 0.161). Within each month, the proportion of patients with migraine headache was generally consistent from days 2–28. The proportion of patients with worsening during the dosing interval did not significantly exceed 50% in any group during any month.

Conclusions

This post hoc analysis supports the consistency of efficacy of galcanezumab across 6 months of treatment and suggests that wearing-off within the dosing interval does not occur on a population level in Japanese patients with episodic migraine.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT02959177.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

A clinically meaningful persistence of efficacy has been observed across 6 months of galcanezumab treatment in Japanese patients with episodic migraine. |

However, the consistency of efficacy within the monthly dosing interval has not been investigated beyond the first month, including within each dosing interval and through the 6-month treatment period. |

What was learned from the study? |

Both weekly and daily analyses indicated that galcanezumab efficacy was generally consistent within the monthly dosing interval when averaged across months 1–6 and for most individual months; worsening (defined as an increase in weekly migraine headache days from weeks 1–2 to weeks 3–4) did not occur at the population level. |

This post hoc analysis of a Japanese randomized clinical trial suggests that the efficacy of galcanezumab in the prevention of episodic migraine does not wear off during the month-long dosing interval. |

Introduction

More than one in ten people worldwide are affected by migraine [1], and approximately 30–40% of people with migraine are considered eligible for preventive treatment [2,3,4]. However, only a minority of eligible people currently take preventive medication, particularly among those with episodic migraine [2,3,4,5,6,7]. Discontinuation rates with traditional preventive medication are high due to tolerability issues and perceived lack of efficacy [5,6,7,8,9]. Moreover, many preventive medications require about 3 months of treatment before efficacy is apparent [10, 11].

Recently developed preventive treatments for migraine that target calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and its receptor exhibit quicker onset of efficacy and better tolerability than older medications [12]. Galcanezumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds CGRP, preventing it from binding to the CGRP receptor [13]. The efficacy and safety of once-monthly galcanezumab for the prevention of migraine have been demonstrated in a series of phase 2 and phase 3 randomized clinical trials in patients with episodic and chronic migraine [14,15,16,17,18]. Despite the confirmed efficacy of galcanezumab and other anti-CGRP antibodies (e.g., fremanezumab and erenumab), some reports suggest that efficacy may wane near the end of the month-long dosing interval [19,20,21]. However, analyses of data from global galcanezumab trials indicate that efficacy remains consistent throughout the dosing interval [22, 23]. Although the absence of “wearing-off” has also been reported in analyses of trial data for fremanezumab [24] and erenumab [19], the definitions of “wearing-off” and the methods of analysis differ among these studies.

The efficacy and safety of galcanezumab in Japanese patients with episodic migraine was previously demonstrated in a phase 2 randomized, placebo-controlled trial [16], leading to the approval in Japan of a once-monthly 120-mg dose for the prevention of migraine in these patients [25]. Although a clinically meaningful persistence of efficacy was observed across six consecutive months of galcanezumab treatment [26], the consistency of efficacy within the monthly dosing interval has not been investigated in Japanese patients beyond the first month, including within each dosing interval and averaged across the 6-month treatment period. The aim of the current analysis of data from the phase 2 trial was to assess galcanezumab efficacy through the monthly dosing interval in Japanese patients by evaluating the number of migraine headache days on a week-by-week basis and the proportion of patients with a migraine headache on a day-by-day basis. In addition, to determine if patients experienced worsening during the dosing interval, the proportion of patients whose number of migraine headache days increased between the first 2 weeks (weeks 1–2) and the last 2 weeks (weeks 3–4) of each month was assessed.

Methods

Study Design

A phase 2, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of galcanezumab in patients with episodic migraine (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02959177) was conducted in Japan between December 2016 and January 2019 [16]. The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice, and the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences’ International Ethical Guidelines for Health-related Research Involving Humans. The protocol was approved by institutional ethics review boards at each study site (Table S1). All patients provided written informed consent. The trial included a screening and washout period, a baseline period, a 6-month double-blind treatment period, and a follow-up period (Fig. S1).

Study Population

The main inclusion criteria for the trial were the following: age 18–65 years; diagnosis of migraine (International Classification of Headache Disorders [ICHD] – 3rd edition beta criteria [27]); and 4–14 migraine headache days/month and ≥ 2 migraine attacks/month in the previous 3 months [16]. A migraine headache day was defined as a calendar day when the patient recorded having a migraine headache or probable migraine headache. The main exclusion criteria were the following: persistent daily headache, cluster headache, or migraine subtypes; ≥ 15 headache days/month or suspected chronic migraine; currently using migraine preventive treatment; or failed to respond to ≥ 3 adequately dosed migraine preventive treatments from different classes. Additional eligibility criteria were reported in detail previously [16].

Treatment Protocol

Following the baseline period, patients were randomized (2:1:1, stratified by baseline monthly migraine frequency [< 8 vs. ≥ 8 monthly migraine headache days]) to subcutaneous placebo, 120-mg galcanezumab, or 240-mg galcanezumab once monthly (Fig. S1). A computer-generated random sequence with an interactive web-response system was used for randomization. At the first injection, patients in the 120-mg galcanezumab group received a 240-mg loading dose.

Outcome Measures

Demographic and migraine-specific data were collected at baseline. During the baseline, treatment, and follow-up periods, patients recorded their migraine headache data in an electronic diary. The primary trial endpoint, reported previously [16], was the mean change from baseline in the number of monthly migraine headache days averaged over the 6-month treatment period; safety results were also reported previously.

For this post hoc analysis of wearing-off, endpoints included the following: change from baseline in the number of weekly migraine headache days averaged for each month (months 1–6) and averaged across 6 months (baseline number of weekly migraine headache days was calculated by normalizing migraine headache days recorded during the baseline period to 7 days); proportion of patients with a migraine headache day analyzed by day (days 2–28) averaged across 6 months and for each month (months 1–6); and the proportion of patients with worsening migraine headache days during the dosing interval for each month (months 1–6). “Worsening” was defined as having a higher mean number of migraine headache days during weeks 3 and 4 than during weeks 1 and 2 within each month; that is, (average of weeks 3 and 4) – (average of weeks 1 and 2) > 0.

Each month was a 30-day period (normalized if the interval was not 30 days) beginning on the day of study drug administration (day 1). The number of weekly migraine headache days in each month was calculated as the number of days in a 7-day period on which a migraine headache occurred. For each month, the first seven calendar days after study drug administration were counted as week 1, the second seven calendar days were counted as week 2, the third seven calendar days were counted as week 3, and the rest of the calendar days until the next injection or the fourth set of seven calendar days, whichever was shorter, were counted as week 4. Post-baseline data were normalized to 7 days for each week (i.e., week 1 = days 2–8; week 2 = days 9–15; week 3 = days 16–22, and week 4 = days 23–29; day 1 was the day of injection for each month).

If a diary entry was missing on a certain day, then that day was excluded from the analysis. For the weekly analysis, the weekly number of migraine headache days was normalized to a 7-day duration by excluding missing days. For example, for a patient with only 2 days of available data for a given week, the normalized weekly number of migraine headache days would be 7 if a migraine headache occurred on both days, 3.5 if a migraine headache occurred on one day, and 0 if a migraine headache did not occur on either day. If the patient discontinued early, then the remaining days were considered as missing days.

Statistical Analysis

Post hoc analyses were performed on the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, defined as all randomized patients who received ≥ 1 dose of galcanezumab or placebo. All analyses were conducted without multiplicity adjustments. A two-sided alpha (type 1 error) of 5% and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used.

The least squares mean change from baseline in weekly migraine headache days was compared between the placebo and galcanezumab groups using a mixed model for repeated measures (MMRM) analysis.

For analysis of the average across 6 months, covariates in the MMRM were baseline monthly number of migraine headache days, treatment, week, month, treatment-by-week interaction, and week-by-month interaction. For analysis of each month, covariates in the MMRM were baseline monthly number of migraine headache days, treatment, week, and treatment-by-week interaction. The difference between week 4 and week 1 was analyzed for each treatment group. The proportion of patients with migraine headache on each day was analyzed using a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM). For analysis of the average across 6 months, covariates in the GLMM were baseline monthly number of migraine headache days, treatment, day, month, and treatment-by-day interaction. For analysis of each month, covariates in the GLMM were baseline monthly number of migraine headache days, treatment, day, and treatment-by-day interaction. For the daily analysis, results for days 29 and 30 of each month are not shown due to small patient numbers. The difference between day 28 and day 2 (the day after injection) in the proportion of patients with migraine headache was analyzed for each treatment group.

The proportion of patients with worsening migraine headache days during the dosing interval was analyzed by a binomial test in comparison to a null rate of 50%. Under the null hypothesis, the proportion is assumed to be 50%; under the alternative hypothesis, the proportion is not 50%. Thus, if a patient had a difference in migraine headache days between weeks 3–4 and weeks 1–2 > 0, then they are considered as “worsening.” However, if the difference is < 0, then they are considered as “improved.” Hypothesis tests were based on a binomial test, using a maximal likelihood estimator with asymptotic CIs. Therefore, if the proportion of patients with worsening migraine headache days was > 50%, it was considered that worsening had occurred.

Results for the approved 120-mg dose of galcanezumab are reported in the main text, and results for the 240-mg dose are reported in the Supplementary Materials. SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Patient Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

As reported previously [16], a total of 459 patients were randomized to placebo (n = 230), 120-mg galcanezumab (n = 115), or 240-mg galcanezumab (n = 114) and were included in the ITT population for analysis. Demographic and disease characteristics were balanced between treatment groups (Table 1). Most patients were female, mean (standard deviation [SD]) age was 44.1 (10.0) years, and the mean (SD) number of monthly migraine headache days at baseline was 8.7 (2.9).

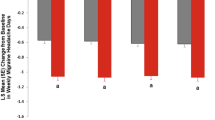

Change From Baseline in Weekly Migraine Headache Days

In the galcanezumab 120-mg group, the mean change from baseline in weekly migraine headache days was consistent and significantly greater than placebo for week 1 through week 4 (Fig. 1). The consistency in efficacy from weeks 1 to 4 was seen in the average across months 1–6, as well as in most individual months. However, there was a significant (p = 0.001) difference in the change from baseline between week 1 and week 4 of month 1 in the galcanezumab 120-mg group (Fig. 1b), which may have reflected the large decrease in migraine headache days seen in the first week of treatment. Similar results were seen in the 240-mg galcanezumab group, although the change from baseline was significantly less (p = 0.003) in week 4 than in week 1 when averaged across months 1–6 (Fig. S2).

a Mean change from baseline in weekly migraine headache days averaged across 6 months in the placebo and galcanezumab 120-mg groups. b Mean change from baseline in weekly migraine headache days for each month (months 1–6) in the placebo and galcanezumab 120-mg groups. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 compared with placebo within each week. CI confidence interval, GMB galcanezumab, LS least squares

Proportion of Patients With a Migraine Headache by Day

When averaged across months 1–6, the estimated proportion of patients with a migraine headache on each day was consistent from day 2 through day 28 in the placebo and 120-mg galcanezumab groups (Fig. 2a), as well as in the 240-mg galcanezumab group (Fig. S3a). The estimated proportion of patients with migraine headache was significantly lower (p < 0.05) with galcanezumab than with placebo on every day in both the 120-mg and 240-mg dose groups. Within the 120-mg galcanezumab group, the proportion of patients with migraine headache was not significantly different between day 2 and day 28 (p = 0.161). However, within the 240-mg galcanezumab group, the proportion of patients with migraine headache was significantly lower on day 2 than on day 28 (p = 0.038).

a Proportion of patients with a migraine headache by day (days 2–28; injection on day 1) averaged across 6 months in the placebo and galcanezumab 120-mg groups. p < 0.001 for galcanezumab versus placebo for each day. b Proportion of patients with a migraine headache by day (days 2–28; injection on day 1) for each month (months 1–6) in the placebo and galcanezumab 120-mg groups. Results for days 29 and 30 are not shown due to small patient numbers. CI confidence interval, GMB galcanezumab

Within each month, the proportion of patients with migraine headache was generally consistent from days 2 to 28, although there was greater variability (larger 95% CIs) compared with the average of months 1–6 in all three treatment groups (Fig. 2b and Fig. S3b). However, in the 120-mg galcanezumab group, there was a significantly greater proportion of patients with a migraine headache on day 28 compared with day 2 during month 1 (p = 0.011) and during month 6 (p = 0.029) (Fig. 2b). In the placebo group, the proportion with a migraine headache was significantly lower on day 28 than on day 2 during month 4 (p = 0.043). In the 240-mg galcanezumab group, there were no significant differences between day 28 and day 2 during any month (Fig. S3b).

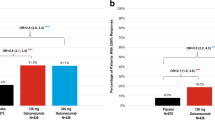

Proportion of Patients With Worsening Migraine Headache Days Within Each Month

The proportion of patients with worsening during the dosing interval (i.e., an increase in the mean number of migraine headache days from weeks 1–2 to weeks 3–4) did not significantly exceed 50% in any treatment group during any month (Fig. 3 and Fig. S4). The proportion of patients with worsening was significantly < 50% at months 1 and 2 in the placebo group and months 2, 4, and 5 in the 120-mg galcanezumab group (Fig. 3). The proportion of patients with worsening was not significantly different from 50% in any month in the 240-mg galcanezumab group (Fig. S4). The mean number of migraine headache days during weeks 1–2 and during weeks 3–4 was consistent across months 1–6 in all three treatment groups (Fig. S5). There was no clear pattern in the difference in number of migraine headache days between weeks 1–2 and weeks 3–4 across months 1–6 in the placebo or 120-mg galcanezumab groups; however, the difference tended to increase from month 1 to month 6 in the 240-mg galcanezumab group.

Proportion of patients with worsening number of migraine headache days during the dosing interval for each month (months 1–6) in the placebo and galcanezumab 120-mg groups. Numbers within the columns indicate n/N. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared with the worsening rate of 50%. CI confidence interval, GMB galcanezumab

Discussion

This post hoc analysis of data from a Japanese randomized clinical trial suggests that the efficacy of galcanezumab in the prevention of episodic migraine does not wear off during the month-long dosing interval. This finding is consistent with previous analyses of data from global galcanezumab trials in patients with episodic and chronic migraine [22, 23]. Similar to one of these previous reports [23], our analysis examined the week-by-week and day-by-day efficacy averaged over the 6-month treatment period. However, we also repeated the analysis for each individual month to assess whether wearing-off might become more apparent with longer treatment. Overall, our results indicate that efficacy generally remains consistent in months 1–6.

In the week-by-week analysis, the mean change from baseline in the weekly number of migraine headache days was significantly greater than placebo during every week of every month in both galcanezumab dose groups, confirming that galcanezumab remains efficacious through the dosing interval. However, there was a significant difference between week 1 and week 4 for the first month in the 120-mg galcanezumab group, which may be related to the large effect experienced during the first week of treatment when patients received a 240-mg loading dose. Interestingly, there was no significant difference between week 1 and week 4 in the first month in the 240-mg galcanezumab group, suggesting that the statistical difference seen in the 120-mg group may have been due to variability in the response to the 240-mg loading dose between the two dose groups. There was, however, a significant difference between week 1 and week 4 in the 240-mg galcanezumab group when averaged over 6 months; despite this, efficacy compared with placebo remained constant throughout the 6-month treatment period. In addition, although not assessed in the current analysis, evidence from previous analyses indicates that galcanezumab reduces headache severity [28]; therefore, even if the number of weekly migraine headache days increases toward the end of the dosing interval, it is likely that headaches are less severe than before galcanezumab treatment. Although these selected results suggest that some relative decrease in efficacy may occur within the dosing interval, the overall pattern indicates that efficacy is maintained across weeks and across months.

Post hoc analyses of the persistence of efficacy have also been conducted for other anti-CGRP antibodies, fremanezumab and erenumab [19, 24]; although the analytical methods used differed from the current galcanezumab study, the overall findings were similar. In the analysis of fremanezumab, there was no major difference in the mean weekly number of migraine headache days between weeks 1–2 and weeks 3–4 within months 3, 6, 9, and 15 of treatment, and no increase in mean weekly migraine headache days between weeks 1 and 2 and weeks 11 and 12 during months 1–3 and months 3–6 [24]. In the analysis of erenumab, there was minimal change in mean weekly migraine headache days in week 4 compared with the average of weeks 1–3 for each of the 6 months of treatment; within a responder subgroup who had ≥ 50% reduction from baseline in weekly migraine headache days in the first 3 weeks, the extent of “wearing-off” did not differ between the erenumab and placebo groups [19]. However, unlike the current analysis of galcanezumab, neither the fremanezumab nor the erenumab studies conducted day-by-day analysis.

Similar to the results of the monthly analysis, in the day-by-day analysis, the estimated proportion of patients with a migraine headache on day 2 through to day 28 was significantly lower in the galcanezumab groups than in the placebo group. In the 120-mg galcanezumab group, there was a significant difference between day 2 and day 28 during month 1 (consistent with the weekly analysis), as well as in month 6. In the 240-mg galcanezumab group, there was a difference between days 2 and 28 when averaged across 6 months, but not within individual months (consistent with the weekly analysis). Although variability was high in all treatment groups, including placebo (Fig. S3), within each month, likely reflecting natural fluctuations in migraine frequency in individual patients [28], averaging across the 6 months demonstrated that efficacy was sustained through the dosing interval in the 120-mg galcanezumab group.

In addition to the weekly and daily analyses of efficacy, we also examined the proportion of patients who experienced worsening during each month. In an analysis of global galcanezumab trials, the proportion of patients with worsening, defined as having an increase of at least two migraine headache days per week from week 2 to week 4 in at least two of the treatment months, was low (≤ 9%) and similar in all treatment groups, including placebo [22]. In our study, we used a simpler definition of worsening, namely, having a greater average number of weekly migraine headache days during weeks 3–4 compared with weeks 1–2. The proportion of patients with worsening was not significantly higher than the null rate of 50% in any treatment group in any month, further suggesting that wearing-off did not occur. In the 120-mg galcanezumab group, the proportion of patients with worsening was significantly lower than 50% during months 2, 4, and 5, again supporting the consistency of efficacy through the 6-month treatment period. However, no significant difference was seen in the 240-mg galcanezumab group. Interestingly, the proportion of patients with worsening was significantly less than 50% in the placebo group during months 1 and 2 (Fig. 3 and Fig. S4). However, the placebo group also did not show any improvement during months 1 and 2, as the mean difference in number of migraine headache days between weeks 1 and 2 and weeks 3 and 4 was essentially zero (Fig. S5). Taken together, although the results of the worsening analysis suggest that the majority of patients in the placebo group showed some improvement, the mean difference data indicate that the improvement was negligible.

This is the first study to report both weekly and daily analyses of galcanezumab efficacy within each monthly dosing interval using data from a 6-month, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. However, as these were post hoc analyses, the results should be considered exploratory. This analysis examined wearing-off over a 6-month treatment period; however, as efficacy across 12 months of treatment has been demonstrated in open-label studies in both Japanese [29] and non-Japanese [30, 31] patients, analyses of data from these studies, as well as from real-world observational studies, examining efficacy within the dosing interval are required to address whether any wearing-off occurs with longer-term treatment. Interpretation of “worsening” data is complex, as patients who have poorer results in weeks 1–2 (e.g., in the placebo group, where the improvement from baseline is small) are less likely to experience worsening in weeks 3–4. High variability in the day-by-day analysis of individual months can be considered random variation, as the daily averages across months 1–6 were consistent. In addition, as data were limited for days 29 and 30, these days were excluded from the day-by-day analysis. Notably, this trial only included patients with episodic migraine, and the results of this analysis may not be applicable to patients with chronic migraine. Finally, migraine headache days were reported by patients and may be subject to potential bias.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this post hoc analysis supports the consistency of efficacy of galcanezumab across 6 months of treatment and suggests that wearing-off within the dosing interval does not occur on a population level in Japanese patients with episodic migraine.

Data Availability

Eli Lilly and Company provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the United States and the European Union and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.

References

Woldeamanuel YW, Cowan RP. Migraine affects 1 in 10 people worldwide featuring recent rise: a systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based studies involving 6 million participants. J Neurol Sci. 2017;372:307–15.

Hirata K, Ueda K, Komori M, et al. Comprehensive population-based survey of migraine in Japan: results of the ObserVational Survey of the Epidemiology, tReatment, and Care Of MigrainE (OVERCOME [Japan]) study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(11):1945–55.

Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, Freitag F, Reed ML, Stewart WF. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68(5):343–9.

Lipton RB, Nicholson RA, Reed ML, et al. Diagnosis, consultation, treatment, and impact of migraine in the US: results of the OVERCOME (US) study. Headache. 2022;62(2):122–40.

Blumenfeld AM, Bloudek LM, Becker WJ, et al. Patterns of use and reasons for discontinuation of prophylactic medications for episodic migraine and chronic migraine: results from the second International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS-II). Headache. 2013;53(4):644–55.

Meyers JL, Davis KL, Lenz RA, Sakai F, Xue F. Treatment patterns and characteristics of patients with migraine in Japan: a retrospective analysis of health insurance claims data. Cephalalgia. 2019;39(12):1518–34.

Ueda K, Ye W, Lombard L, et al. Real-world treatment patterns and patient-reported outcomes in episodic and chronic migraine in Japan: analysis of data from the Adelphi migraine disease specific programme. J Headache Pain. 2019;20:68.

Hepp Z, Bloudek LM, Varon SF. Systematic review of migraine prophylaxis adherence and persistence. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20(1):22–33.

Vécsei L, Majláth Z, Szok D, Csáti A, Tajti J. Drug safety and tolerability in prophylactic migraine treatment. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2015;14(5):667–81.

Araki N, Takeshima T, Ando N, et al. Clinical practice guideline for chronic headache 2013. Neurol Clin Neurosci. 2019;7(5):231–59.

Stark RJ, Stark CD. Migraine prophylaxis. Med J Aust. 2008;189(5):283–8.

Ferrari MD, Goadsby PJ, Burstein R, et al. Migraine. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2022;8(1):2.

Dodick DW, Goadsby PJ, Spierings ELH, Scherer JC, Sweeney SP, Grayzel DS. Safety and efficacy of LY2951742, a monoclonal antibody to calcitonin gene-related peptide, for the prevention of migraine: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(9):885–92.

Detke HC, Goadsby PJ, Wang S, Friedman DI, Selzler KJ, Aurora SK. Galcanezumab in chronic migraine: the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled REGAIN study. Neurology. 2018;91(24):e2211–21.

Mulleners WM, Kim B-K, Láinez MJA, et al. Safety and efficacy of galcanezumab in patients for whom previous migraine preventive medication from two to four categories had failed (CONQUER): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(10):814–25.

Sakai F, Ozeki A, Skljarevski V. Efficacy and safety of galcanezumab for prevention of migraine headache in Japanese patients with episodic migraine: a phase 2 randomized controlled clinical trial. Cephalalgia Rep. 2020;3:1–10.

Skljarevski V, Matharu M, Millen BA, Ossipov MH, Kim B-K, Yang J-Y. Efficacy and safety of galcanezumab for the prevention of episodic migraine: results of the EVOLVE-2 phase 3 randomized controlled clinical trial. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(8):1442–54.

Stauffer VL, Dodick DW, Zhang Q, Carter JN, Ailani J, Conley RR. Evaluation of galcanezumab for the prevention of episodic migraine: the EVOLVE-1 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(9):1080–8.

Dodick DW, Blumenfeld AM, Halker Singh RB, et al. Post hoc analysis of clinical trial data and pharmacokinetic data to assess wearing-off of erenumab within monthly treatment cycle. Headache. 2023;63(2):233–42.

Restrepo S. Wearing off in CGRP fremanezumab-VFRM and galcanezumab-GNLM. Headache. 2020;60(S1):1–156.

Robblee J, Devick KL, Mendez N, Potter J, Slonaker J, Starling AJ. Real-world patient experience with erenumab for the preventive treatment of migraine. Headache. 2020;60(9):2014–25.

Ailani J, Kuruppu DK, Rettiganti M, et al. Does “wearing off” of efficacy occur in galcanezumab-treated patients at the end of the monthly treatment cycle? Post hoc analyses of four phase III randomized trials. Headache. 2022;62(2):198–207.

Pozo-Rosich P, Samaan KH, Schwedt TJ, Nicholson RA, Rettiganti M, Pearlman EM. Galcanezumab provides consistent efficacy throughout the dosing interval among patients with episodic and chronic migraine: a post hoc analysis. Adv Ther. 2021;38(6):3154–65.

Blumenfeld AM, Stevanovic DM, Ortega M, et al. No “wearing-off effect” seen in quarterly or monthly dosing of fremanezumab: subanalysis of a randomized long-term study. Headache. 2020;60(10):2431–43.

EMGALITY® (galcanezumab) [package insert]. Kobe, Japan: Eli Lilly Japan K.K.; 2021.

Igarashi H, Shibata M, Ozeki A, Day KA, Matsumura T. Early onset and maintenance effect of galcanezumab in Japanese patients with episodic migraine. J Pain Res. 2021;14:3555–64.

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33(9):629–808.

Igarashi H, Shibata M, Ozeki A, Matsumura T. Galcanezumab effects on migraine severity and symptoms in Japanese patients with episodic migraine: secondary analysis of a phase 2 randomized trial. Neurol Ther. 2023;12(1):73–87.

Hirata K, Takeshima T, Sakai F, et al. A long-term open-label safety study of galcanezumab in Japanese patients with migraine. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2021;20(6):721–33.

Camporeale A, Kudrow D, Sides R, et al. A phase 3, long-term, open-label safety study of galcanezumab in patients with migraine. BMC Neurol. 2018;18:188.

Pozo-Rosich P, Detke HC, Wang S, et al. Long-term treatment with galcanezumab in patients with chronic migraine: results from the open-label extension of the REGAIN study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2022;38(5):731–42.

Japanese Society of Neurology. Clinical Practice Guideline for Chronic Headache 2013. https://www.neurology-jp.org/guidelinem/ch/index.html. Accessed May 26, 2023.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all study participants.

Medical Writing

Medical writing assistance was provided by Rebecca Lew, PhD, CMPP, and Prudence Stanford, PhD, CMPP, of ProScribe – Envision Pharma Group, and was funded by Eli Lilly Japan K.K. and Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited. ProScribe’s services complied with international guidelines for Good Publication Practice.

Funding

This study was funded by Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Kobe, Japan, manufacturer/licensee of galcanezumab in Japan. Eli Lilly Japan K.K. and Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited funded the journal’s Rapid Service Fee.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published. All authors participated in the interpretation of study results, and in the drafting, critical revision, and approval of the final version of the manuscript. Yuka Tanji, Akichika Ozeki, Hideyuki Imagawa, and Mika Komori were involved in the study design. Mamoru Shibata and Atsuko Nihira were investigators in the study. Mamoru Shibata, Atsuko Nihira, and Akichika Ozeki were involved in data collection. Akichika Ozeki conducted the statistical analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Mamoru Shibata and Atsuko Nihira have received honoraria from Amgen K.K., Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited, Eli Lilly Japan K.K., and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Yuka Tanji, Akichika Ozeki, Hideyuki Imagawa, and Mika Komori are employees of Eli Lilly Japan K.K. and minor shareholders in Eli Lilly and Company.

Ethical Approval

The protocol was approved by the local institutional review boards (Table S1). All patients provided written informed consent before any study procedures. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice, and the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences’ International Ethical Guidelines for Health-related Research Involving Humans.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shibata, M., Nihira, A., Tanji, Y. et al. Galcanezumab Efficacy Through the Dosing Interval in Japanese Patients with Episodic Migraine: Post Hoc Analysis of a Phase 2 Randomized Trial. Neurol Ther 12, 2007–2019 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-023-00534-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-023-00534-0