Abstract

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is one of the leading causes of hospitalization worldwide. In Thailand, data on HF burden remains limited. This study aimed to describe comprehensive evidence detailing the HF prevalence, hospital admission rates, in-hospital mortality, and overall mortality rates at the hospital level.

Method

All eligible adult patients’ medical records from 2018 and 2019 were analyzed retrospectively at five hospitals in different regions. The patients were diagnosed with HF, as indicated by the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 code I50. Descriptive statistics were used to examine the hospital burden as well as patients’ clinical and outcome data.

Results

A total of 7384 patients with HF were identified from five tertiary hospitals. Around half of the patients were male. The mean age was 67 years, and the main health insurance scheme was the Universal Coverage Scheme. The prevalence of HF was 0.1% in 2018 and 0.2% in 2019. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) was the most common type of HF in both visits, followed by heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF). The proportion of HF hospitalizations was 1.2% in 2018 and 1.5% in 2019. The proportion of HF rehospitalizations versus hospitalizations in patients with HF was 22.7% in 2018 and 23.9% in 2019. The risk of rehospitalization was highest at 180 days after hospital discharge (87.8%). Among the patients with HF, the proportion of all-cause mortality was 9.1% in 2018 and 8.0% in 2019. Most of the deaths occurred within 30 days after hospitalization.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that the burden of HF in terms of hospitalization and in-hospital mortality was notably high when compared to similar studies conducted in Thailand and other countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

There is limited data on population-based studies that have investigated the prevalence of heart failure (HF), hospital admission rates, in-hospital mortality, and overall mortality rates in Thailand. |

Understanding the healthcare burden caused by HF is important to minimizing and improving patients care, particularly given Thailand’s aging population. |

Our results revealed that the burden of HF in terms of hospitalization and in-hospital mortality was much higher than the previous studies. |

There is still an urgent need for improved care of patients with HF to reduce the total burden of HF in Thailand. |

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) presents a significant global public health challenge [1], affecting a substantial number of individuals worldwide. According to current estimates, around 26 million people worldwide have been diagnosed with HF [2]. However, the prevalence varies across different regions. In the previous population-based studies, Malaysia had the highest prevalence of HF among Asian nations (6.7%), followed by Singapore (4.5%), China (1.3%), and Japan (1%) [3]. Surprisingly, no population-based study has investigated the prevalence of HF in Thailand. Nevertheless, there is a belief that the burden of HF in Thailand is steadily on the rise. This escalation is attributed to HF serving as the ultimate progression of cardiovascular disease (CVD), which is a leading cause of mortality in Thailand [4]. Moreover, the frequency of HF surges in tandem with advancing age, a trend that is poised to magnify within nations marked by aging populations, including Thailand [5].

HF is one of the leading causes of hospital admissions worldwide. In developed countries, 1–4% of all hospital admissions are accounted for by HF [6], while the prevalence of HF in hospitalized patients ranged from 3.4% to 6.7% in Asian countries [7]. In addition, approximately 17–45% of these hospitalized patients do not survive beyond 1 year following their admission, with the majority succumbing within 5 years [8,9,10]. In Thailand, comprehensive evidence detailing the HF prevalence, hospital admission rates, in-hospital mortality, and overall mortality rates remains limited. Findings from the first HF registry in Thailand, the Thai Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Registry (Thai ADHERE), disclosed an in-hospital mortality rate of 5.5% for patients with HF in the period from 2006 to 2007 [11]. Interestingly, there was a subsequent decline in in-hospital mortality, from 4.4% in 2008 to 3.8% in 2013 [12]. The increased survival rate among patients with HF might be due to advances in innovative medicines and improved patient management systems. However, the rates of 1-year rehospitalization and mortality rate of patients with HF in Thailand remained notably elevated, standing at 34% and 28.5%, respectively [12].

Because of the increased frequency of hospitalizations and the adverse outcomes after hospitalization, the care of patients with HF imposes a significant economic burden. This burden is reflected in healthcare expenditures, which constitute approximately 1–3% of the total healthcare spending in North America [13] and Western Europe [14]. This economic burden primarily arises from the frequency and duration of hospital stays among patients with HF. Understanding the healthcare load caused by HF is crucial to minimizing and improving the consequences of this life-threatening condition, particularly given Thailand’s aging population. Thus, we conducted a hospital-based retrospective cohort study to assess the burden of HF in Thailand. This study examined the prevalence of HF in patients who visited the hospital (including outpatient and inpatient visits) and the frequency of HF hospitalizations. All-cause and CVD mortality rates among patients with HF, as well as the utilization of hospital resources and associated costs directly related to HF cases, were also estimated.

Methods

Study Settings and Participants

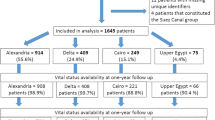

This study was a retrospective cohort study conducted in the five tertiary hospitals (Lampang, Chonburi, Bhumibol Adulyadej, Udonthani, and Queen Sirikit Heart Center of the Northeast, Khon Kaen University) during 2018–2019. These hospitals are located in different geographic areas with varying service levels, including three advanced-level hospitals in the Ministry of Public Health (Lampang, Chonburi, and Udonthani), one medical school hospital (Queen Sirikit Heart Center of the Northeast), and one military hospital (Bhumibol Adulyadej). The study’s participants were adult patients with the diagnosis of HF.

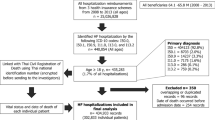

The study’s participants were identified by the ICD-10 codes I50 (all heart failure) and I50.1 (left ventricular heart failure) from the study’s hospital databases. Both newly diagnosed and existing patients with HF were included in this study if their ages were 18–99 years old and they had at least two hospital visits during 2018–2019. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study’s protocol was approved by the central research ethics committee (CREC) (COA-CREC029/2022) and the local institutional review board (IRB) of each participating institution. A list of IRBs can be found in the supplementary material. As a result of the retrospective nature of the study, informed consent was exempted by the IRB.

Data Collection

Demographic data of participants, including age, sex, and health reimbursement schemes, as well as the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of the patients with HF, were collected by reviewing the medical records. Costs and workload of hospital staff due to HF hospitalization were also gathered. The workload of hospital staff was collected from cardiologists, non-cardiologists, and nurses who took care of patients with HF in an inpatient setting. Working hours were calculated from the duration in minutes that each staff member spent caring for patients with HF per day as reported by hospital staff. The total costs of outpatient (OPD), inpatient (IPD), and emergency department (ED) visits of patients with HF were retrieved from the hospital records. The total cost included medication, laboratory, imaging, device, and surgical costs.

Types of Heart Failure

HF was classified into three main subtypes: (1) heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), LVEF less than 40%; (2) heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF), LVEF between 40% and 50%; and (3) heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), LVEF ≥ 50% based on the Thai HF guideline 2019 in all endpoints. The type of HF may be confirmed via hospital data (which includes results of echocardiograms, for example) where available.

Outcomes of Interest

The primary outcome of this study was the burden of HF, including hospital visits, unscheduled hospital visits, hospitalization, and HF rehospitalization. A hospital visit was defined as a hospital visit at either OPD, IPD, or ED that had a principal or secondary diagnosis of HF, while an unscheduled hospital visit was defined as an unscheduled visit at OPD or ED. Hospitalization was defined as an inpatient admission to an acute facility for HF, such as a hospital ward, intensive care unit (ICU), critical care unit (CCU), or intensive cardiac care unit (ICCU). Rehospitalization was defined as an inpatient admission to an acute facility for HF within 30, 60, and 180 days after discharge from a previous hospitalization. Data about hospital visits, unscheduled visits, hospitalization, and rehospitalization were retrieved from the study’s hospital databases.

The secondary outcomes were the prevalence of HF, all-cause mortality, and CV mortality in patients with HF. All-cause mortality was defined as the death from any cause, while CV mortality was defined as the death related to cardiovascular events. All-cause and CV mortality in the participants were verified by retrieving the data from the study’s hospital databases.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data was presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) if the data was normally distributed; otherwise, median and range were applied instead. Categorical data was presented as frequency and percentage (%).

The prevalence of HF was calculated by dividing the total number of identified patients with HF by the total number of patients in the study’s hospitals. Proportions of hospital visits were estimated by dividing the number of hospital visits of patients with HF by the number of total hospital visits from all patients, while proportions of hospitalizations were calculated by dividing the number of hospitalizations from all causes in patients with HF by the total number of hospitalizations from all patients in the hospitals.

All-cause mortality and CV mortality rates were calculated by dividing the number of deaths from any causes in identified patients with HF by the number of deaths from any causes in all patients and by dividing the number of deaths from cardiovascular events in patients with HF by the number of deaths in all patients, respectively.

The proportion of unscheduled OPD and ED visits of patients with HF was estimated by dividing the number of unscheduled visits from HF by the number of total hospital visits in identified patients with HF. The proportion of HF rehospitalization was calculated by dividing the number of HF rehospitalizations by the number of HF hospitalizations among identified patients with HF.

Rates of HF rehospitalization at 30, 60, and 180 days were calculated by dividing the number of rehospitalizations due to HF at 30, 60, and 180 days after hospital discharge by the total HF rehospitalizations of identified patients with HF.

The 95% confidence intervals (CI) of all proportions and rates were also estimated. All analyses were performed by the SAS program version 9.4.

Results

A total of 7384 patients with HF were identified from five tertiary hospitals: 22.3% Lampang, 22.2% Chonburi, 24.4% Bhumibol Adulyadej, 22.9% Udonthani, and 8.3% Queen Sirikit Heart Center of the Northeast. Of these patients, 3180 and 4697 patients were identified from 2,399,555 patient visits in 2018 and 2,487,960 patient visits in 2019. Thus, the prevalence of HF in this study was 0.1% in 2018 and 0.2% in 2019.

The characteristics of the patients with HF were comparable between patients identified from visits in 2018 and visits in 2019, as presented in Table 1. Around half of patients with HF were male. The mean age was 67 years, and the main health insurance scheme was the Universal Coverage Scheme (UHC). Only 1802 and 2689 patients had LVEF data from visits in 2018 and 2019, respectively. The mean LVEF (SD) for patients reported in 2018 and 2019 was 46.5% (18.3) and 45.9% (18.2), respectively.

Types of Heart Failure

The proportion of each subtype of HF was comparable between visits in 2018 and 2019 (Table 2). HFpEF was the most common type of patient with HF (44.3%), followed by HFrEF and HFmrEF. HFrEF and HFmrEF were more commonly found in men (64.7% and 52.0% in 2018, and 62.3% and 54.6% in 2019) than women, while HFpEF was more common in women (55.9% and 56.7% in 2018 and 2019, respectively). The mean age of patients with HF was highest in HFpEF, followed by HFmrEF and HFrEF subtypes (Table 2).

The estimated prevalence of HFrEF, HFmrEF, and HFpEF was 0.1%, 0.02%, and 0.1% in 2018 and 0.1%, 0.04%, and 0.1% in 2019, respectively.

Burden of Heart Failure

Hospital Visits

The number of hospital visits for patients with HF was 6811 in 2018 and 10,564 in 2019, with a median of 1 visit per year (range 1–18) for 2018 and 1 visit per year (range 1–20) for 2019. The proportion of hospital visits from patients with HF among the total number of hospital visits from all patients was 0.1% in 2018 and 0.2% in 2019. The median number of hospital visits annually among patients with HFrEF, HFmrEF, and HFpEF was 2, 1, and 1 in 2018 and 2, 2, and 1 in 2019, respectively. In 2018, the number of visits was highest in IPD (47.0%), followed by OPD (45.6%) and ED (7.5%), while in 2019, it was highest in OPD (52.4%), followed by IPD (41.7%) and ED (5.9%).

Hospitalization

The proportions of hospitalizations from patients with HF among the total number of hospitalizations from all patients were 1.2% in 2018 and 1.5% in 2019 (Table 3). The proportion of hospitalization across three types of HF was greatest in patients with HFpEF (0.3%) for visits in 2018 and in patients with HFrEF (0.5%) for visits in 2019. For both years, patients with HFmrEF had the lowest proportion of HF hospitalizations (Table 3).

Among IPD visits, most patients with HF were admitted to the hospital ward (92.4% in 2018 and 92.5% in 2019); see Table 4. The reason for hospital admission was mostly related to HF symptoms (87.1% in 2018 and 87.2% in 2019). The in-hospital mortality in patients with HF was 11.4% in 2018 and 10.8% in 2019, with cardiovascular events being the most common cause of death (88.0% in 2018 and 83.5% in 2019). The risk of in-hospital death was highest in patients with HFrEF (9.1% in 2018 and 9.2% in 2019).

Among patients with HF who visited the ED, around 4% of them died when visiting the ED, with cardiovascular events being the most common cause of death (93.3% in 2018 and 77.3% in 2019).

Rehospitalization and Unscheduled Visits

Among patients with HF who were admitted to the hospital, around one-fourth of them were readmitted. The proportion of HF rehospitalizations among the number of patients hospitalized with HF was 22.7% in 2018 and 23.9% in 2019 (Table 5). The proportion of rehospitalization was highest in patients with HFrEF for both years.

The risk of rehospitalization was highest at 180 days after hospital discharge. The proportions of HF rehospitalization at 30, 60, and 180 days were 29.9%, 53.0%, and 87.8% in 2018 and 31.1%, 50.7%, and 89.9% in 2019, respectively.

For the unscheduled visits at OPD and ED, the proportion of unscheduled visits by patients with HF was 10.0% in 2018 and 9.0% in 2019 (Table 5). The proportion of unscheduled visits was highest in patients with HFrEF in 2018 (9.4%), while the proportion was highest in patients with HFpEF in 2019 (6.6%).

All-Cause and CV Mortality

The proportion of all-cause deaths in patients with HF among all patients in the hospitals was 3.3% in 2018 and 4.2% in 2019 (Table 6). Among identified patients with HF, the proportion of all-cause mortality was 9.1% in 2018 and 8.0% in 2019. Most of the deaths occurred within 30 days after hospitalization. The proportion of all-cause mortality was highest in patients with HFrEF in both years.

The proportion of CV deaths among all patients was 3.0% in 2018 and increased to 3.5% in 2019. In comparison, the rate of CV-related mortality among identified patients with HF was 8.0% in 2018 and 6.6% in 2019. The proportion of CV deaths was highest in patients with HFrEF in both years. While the proportion of non-CV-related mortality was greater in patients with HFmrEF and HFpEF than in patients with HFrEF.

Cost of Heart Failure Utilization

The median (IQR) cost of OPD visits for patients with HF was 55 (101) USD in 2018 and 49 (86) USD in 2019. The total cost of an IPD visit was 511 (1,053) USD in 2018 and 515 (908) USD in 2019. The median total cost of an ED visit was 103 (109) USD in 2018 and 108 (107) USD in 2019. The median cost of OPD visits among patients with HFrEF, HFmrEF, and HFpEF was greatest in HFmrEF, HFrEF, and HFpEF, respectively, following a similar pattern in the IPD setting, but was somewhat different in the ED visits, where HFpEF was reported to have the highest cost.

Discussion

In this study, we observed a prevalence of patients with HF of 0.1% in 2018 and 0.2% in 2019. These findings were lower than the prevalence reported in a previous study conducted in Thailand during 2006 and 2007 (0.4%), and the prevalence of HF in Germany, Norway, and the USA was reported as 3.9%, 2.4%, and 3.0%, respectively [15]. The lower prevalence of HF in our study might be attributed to advances in the management of conditions such as coronary heart disease and valvular heart disease, both of which can ultimately lead to the development of HF. However, the higher prevalence of HF reported in high-income countries may be attributed to their more robust healthcare systems, which offer better access to medical care when compared to Thailand.

According to the subtypes of HF, we reported that around 40% of patients with HF had HFrEF. This result contrasted with the findings of the ASAIN-HF study, which included patients from 11 Asian countries and found that 81% of patients with HF had HFrEF [16]. However, studies in Japan [17] and China [18] found HFrEF rates of 36% and 40%, respectively, which were close to our findings. The prevalence of HF subtypes in our analysis may have been underestimated since only 57% of total patients obtained echo reports.

In our research, the hospitalization rate for patients with HF was around 1.5%, which was much higher than the hospitalization rate reported in a previous study done in Thailand (0.1%–0.2%), which examined data from inpatient medical cost claims from 2008 to 2013, comprising beneficiaries of three main public health security schemes, with the goal of representing the overall community hospitalization rate [12]. In contrast, our findings were based on a hospital setting. Furthermore, the observed hospitalization rate was greater than in the Japan study, which was done in six general hospitals during 2003 and 2012; the prevalence rate of HF-related hospitalization varied from 181 to 238 per 100,000 person-years [19].

In terms of hospitalization outcomes, around 30% of patients who were first admitted to the hospital were readmitted within 30 days after their discharge. This rehospitalization rate was higher than the 13.7% reported in the Thai HF Snapshot Study, which was done across five Thai universities and tertiary hospitals [20]. Moreover, our study showed a higher in-hospital mortality rate than other studies (11%). This was in contrast to the previous retrospective study’s in-hospital mortality rate of 4% [12] and the Thai Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Registry’s in-hospital mortality rate of 5% [11]. The disparity in in-hospital mortality rates between our study and previous investigations might be related to the differences in study settings. The previous research relied on healthcare expenditure claims data from three major public health security systems covering the entire Thai population, while our analysis included data from tertiary hospitals. Furthermore, the patients with HF in our research may have had more severe conditions than those in the prior study, since increasing disease severity is frequently associated with a higher risk of mortality. When compared to studies done in South Korea (6.6%) [21] and China (4.1%), our research found a greater in-hospital mortality rate [22].

The all-cause mortality rate for patients with HF was 9.1% in 2018 and slightly decreased to 8.0% in 2019. These numbers contrast with the findings of a previous study done in Thailand, which found that 1-year mortality rates for patients with HF varied from 31.8% in 2008 to 28.5% in 2013 [12]. Similarly, our findings are consistent with those of the ASIAN-HF registry, which found a 1-year all-cause mortality rate of 9.6% among symptomatic patients with HF [16]. The Korean Heart Registry also found a 1-year mortality rate of 9.2% among patients with HFrEF [21]. The significant reduction in observed mortality rates might be related to advances in HF management in Thailand. Furthermore, this study found that the risk of death was highest among patients with HFrEF. The discovery is consistent with findings from other research done not just in Asian countries [23], but also in Western countries [24], highlighting the consistent nature of this trend across multiple geographic locations.

Strengths and Limitations

This was the first study in Thailand to assess the prevalence of HF in a hospital setting. It included data from five tertiary hospitals located across nearly all regions of Thailand. Consequently, the results of our study may be generalized to other patients with HF in Thailand who sought care at hospitals of a similar caliber. Additionally, our study offers a holistic view of the HF burden in Thailand, covering various dimensions of the condition’s impact.

However, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations in our study. Firstly, the hospitals included in our study were predominantly regional and university hospitals, which may introduce a potential bias known as referral bias. This means that our study participants might have had more severe disease profiles. Secondly, our study employed a retrospective study design, which collected data from medical records and hospital databases, resulting in some instances of missing information. For example, LVEF data was available for only 57% of the participants, and we were unable to gather data on certain crucial factors that could impact the outcomes of patients with HF. Thirdly, our identification of HF cases relied solely on the ICD-10 coding system. This method may have introduced a misclassification bias, potentially leading to inaccuracies in the classification of HF cases. Fourthly, additional patient characteristics and demographic data, such as comorbidities and pharmaceutical history, were not collected in this study. Furthermore, the p values for comparisons of the study data between 2018 and 2019 are not shown, suggesting that further research should be undertaken using these data. Lastly, our study did not assess long-term outcomes for patients with HF. Therefore, there is a need for a prospective cohort study with a meticulously designed data collection process and long-term patient follow-up. Such a study is essential to accurately estimating the impact and burden of HF, both in the short and long term.

Conclusion

Our study found that the burden of HF in terms of hospitalization and in-hospital mortality was notably high when compared to similar studies conducted in Thailand and other countries. Furthermore, despite a slight decrease in mortality rates over time, patients with HF still faced a substantial risk of mortality. Consequently, there is a pressing need for enhanced treatment and care for patients with HF in both inpatient and outpatient settings to mitigate the overall burden of HF in Thailand.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(12):e67–e492. https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000558.

Bui AL, Horwich TB, Fonarow GC. Epidemiology and risk profile of HF. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8(1):30–41.

Ponikowski P, Anker SD, AlHabib KF, et al. HF: preventing disease and death worldwide. ESC HF. 2014;1(1):4–25.

Global health estimates: leading causes of death. WHO. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-leading-causes-of-death. Accessed 11 Jan 2024.

Mosterd A, Hoes AW. Clinical epidemiology of HF. Heart. 2007;93(9):1137–46.

Health care quality indicators—primary care—congestive HF hospital admissions. OECD. https://stats.oecd.org/. Accessed 11 Jan 2024.

Shimokawa H, Miura M, Nochioka K, et al. HF as a general pandemic in Asia. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17(9):884–92.

Roger VL, Weston SA, Redfield MM, et al. Trends in HF incidence and survival in a community-based population. JAMA. 2004;292(3):344–50.

Tavazzi L, Senni M, Metra M, et al. Multicenter prospective observational study on acute and chronic HF: one-year follow-up results of IN-HF (Italian Network on HF) outcome registry. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(3):473–81.

Jhund PS, Macintyre K, Simpson CR, et al. Long-term trends in first hospitalization for HF and subsequent survival between 1986 and 2003: a population study of 5.1 million people. Circulation. 2009;119(4):515–23.

Laothavorn P, Hengrussamee K, Kanjanavanit R, et al. Thai Acute Decompensated HF Registry (Thai ADHERE). CVD Prev Control. 2010;5(3):89–95.

Janwanishstaporn S, Karaketklang K, Krittayaphong R. National trend in HF hospitalization and outcome under public health insurance system in Thailand 2008–2013. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022;22(1):203.

Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121(7):e46–215.

Neumann T, Biermann J, Erbel R, et al. HF: the commonest reason for hospital admission in Germany: medical and economic perspectives. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009;106(16):269–75.

Savarese G, Becher PM, Lund LH, et al. Global burden of HF: a comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc Res. 2023;118(17):3272–87.

MacDonald MR, Tay WT, Teng TK, et al. Regional variation of mortality in HF with reduced and preserved ejection fraction across Asia: outcomes in the ASIAN-HF registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(1):e012199.

Shiga T, Suzuki A, Haruta S, et al. Clinical characteristics of hospitalized HF patients with preserved, mid-range, and reduced ejection fractions in Japan. ESC Heart Fail. 2019;6(3):475–86.

Hao G, Wang X, Chen Z, et al. Prevalence of HF and left ventricular dysfunction in China: the China Hypertension Survey, 2012–2015. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21(11):1329–37.

Honma M, Tanaka F, Sato K, et al. Sex-specific temporal trends in the incidence and prevalence of hospitalized patients with preserved versus reduced left ventricular ejection fraction HF: a Japanese community-wide study. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2015;9:15–21.

Tankumpuan T, Sindhu S, Perrin N, et al. A multi-site Thailand HF Snapshot Study. Heart Lung Circ. 2022;31(1):85–94.

Youn YJ, Yoo B-S, Lee J-W, et al. Treatment performance measures affect clinical outcomes in patients with acute systolic heart failure: report from the Korean Heart Failure Registry. Circ J. 2012;76(5):1151–8.

Zhang Y, Zhang J, Butler J, et al. Contemporary epidemiology, management, and outcomes of patients hospitalized for HF in China: results from the China HF (China-HF) registry. J Card Fail. 2017;23(12):868–75.

Tsuchihashi-Makaya M, Hamaguchi S, Kinugawa S, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized patients with HF and reduced vs preserved ejection fraction. Report from the Japanese Cardiac Registry of HF in Cardiology (JCARE-CARD). Circ J. 2009;73(10):1893–900.

Chioncel O, Lainscak M, Seferovic PM, et al. Epidemiology and one-year outcomes in patients with chronic HF and preserved, mid-range and reduced ejection fraction: an analysis of the ESC HF Long-Term Registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19(12):1574–85.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Novartis (Thailand) Limited. Novartis also funded the journal’s publication fee.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All analyses were performed by a contracted research organization (CRO), the Center of Excellence for Biomedical and Public Health Informatics (BIOPHICS) of Mahidol University, whose results were verified by the authors. Panyapat Jiampo, Thidaporn Tangkittikasem, Thanita Boonyapiphat, Vichai Senthong, and Artit Torpongpun drafted, reviewed, provided feedback on subsequent versions. Artit Torpongpun and Panyapat Jiampo took lead in final revision of the manuscript before submitting it for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Panyapat Jiampo, Thidaporn Tangkittikasem, Thanita Boonyapiphat, Vichai Senthong, and Artit Torpongpun have nothing to disclose.

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study’s protocol was approved by the central research ethics committee (CREC) (COA-CREC029/2022) and the local institutional review board (IRB) of each participating institution. A list of IRBs can be found in the supplementary material. As a result of the retrospective nature of the study, informed consent was exempted by the IRB.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiampo, P., Tangkittikasem, T., Boonyapiphat, T. et al. Real-World Heart Failure Burden in Thai Patients. Cardiol Ther 13, 281–297 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40119-024-00355-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40119-024-00355-8