Abstract

Introduction

Biologics are a standard therapy for patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis, yet treatment persistence is essential to achieve disease control. Compared with other biologics, ustekinumab has been associated with lower rates of discontinuation and better adherence among patients with psoriasis, but prior studies have included limited data from the period after approval of self-administration for ustekinumab. This study was conducted to assess discontinuation risk among patients with plaque psoriasis initiating ustekinumab or other biologics.

Methods

Adults with psoriasis and one or more claim for ustekinumab, secukinumab, adalimumab, or ixekizumab were identified in Optum’s de-identified Clinformatics Data Mart Database (1 January 2010 to 30 June 2019). Treatment discontinuation was defined as a gap in days of therapy supply based on (1) each drug’s per-label frequency of administration (main analysis) or (2) > 90 days (sensitivity analysis). Differences in baseline characteristics between the ustekinumab and other cohorts were adjusted with entropy balancing. Risk of discontinuation was compared with Cox proportional hazard models.

Results

Overall, 2230 patients were included in the ustekinumab cohort, with 1807 in the secukinumab, 4483 in the adalimumab, and 535 in the ixekizumab cohorts (mean age 49.0 years, 49.3% female for all cohorts). In the main analysis, risk of discontinuation for the ustekinumab cohort was 62.2% lower than for adalimumab, 46.4% lower than for secukinumab, and 43.8% lower than for ixekizumab cohorts (all p < 0.001). Sensitivity analyses revealed no significant differences between the ustekinumab and other cohorts.

Conclusions

Patients with psoriasis initiating ustekinumab had lower risk of treatment discontinuation compared with other biologics when discontinuation was based on each drug’s per-label frequency of administration. This finding may help inform choice of biologic based on compliance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

While biologics are a standard therapy for moderate-to-severe psoriasis, patients frequently discontinue treatment or demonstrate poor adherence, which is associated with inferior health outcomes. |

Compared with other biologics, ustekinumab has been associated with lower rates of discontinuation and better adherence, but prior studies have included limited data from the period after approval of self-administration for ustekinumab. |

This study was conducted to compare treatment discontinuation among patients with psoriasis who initiated ustekinumab, secukinumab, or other biologics (i.e., adalimumab and ixekizumab), and describe treatment adherence and switching patterns with these agents. |

What was learned from the study? |

Patients with psoriasis initiating ustekinumab had a lower risk of treatment discontinuation compared with other biologics when discontinuation was based on each drug’s per-label frequency of administration. |

These results may help inform the choice of biologic therapy based on compliance, which may subsequently improve outcomes of patients with psoriasis. |

Introduction

Plaque psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disorder estimated to affect 3.2% of adults annually in the USA [1]. Although skin lesions are a hallmark of the disease, psoriasis is increasingly recognized as a multisystem disorder with comorbidities such as psoriatic arthritis, and cardiovascular and psychiatric conditions [2,3,4,5].

While most patients with mild-to-moderate psoriasis achieve adequate disease control with topical therapies or phototherapy, systemic therapies may be necessary to treat patients with moderate-to-severe disease [3]. Since their introduction, biologics have been replacing traditional systemic therapies as a treatment for moderate-to-severe psoriasis [6]. A number of biologics are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treating patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis; these agents inhibit specific pathways involving various cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-12, IL-23, and IL-17A [7].

Patients initiated on biologics frequently discontinue therapy [8,9,10,11,12,13,14] or demonstrate poor adherence [15], which is associated with inferior health outcomes [16, 17]. Lack of compliance may be due to a number of factors, including drug tolerability, convenience, cost, and effectiveness, and overall patient satisfaction with treatment [18]. Prior studies that assessed discontinuation and adherence found significant differences between various biologics in the USA [8,9,10, 19,20,21]. In these studies, ustekinumab, compared with other biologics, was almost invariably associated with lower rates of discontinuation and better adherence.

Nonetheless, most prior studies were conducted before approval of the first IL-17A antagonist. Further, most had no or limited data from the period after approval of self-administration for ustekinumab (21 May 2013) [22, 23]. Thus, the previous literature may no longer reflect contemporary biologic treatment patterns among patients with psoriasis [24]. This study sought to address this gap in knowledge by comparing treatment discontinuation among patients with psoriasis, who initiated ustekinumab, secukinumab, or other biologics (i.e., adalimumab and ixekizumab), and describing treatment adherence and switching patterns with these agents.

Materials and Methods

Data Source

Data derived from Optum’s de-identified Clinformatics Data Mart Database (1 January 2010 to 30 June 2019) were used for these analyses. The database contains information on demographics and health plan eligibility, as well as medical and prescription drug claims of commercially insured and Medicare Advantage beneficiaries nationwide. All data were de-identified and complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act; therefore, institutional review board approval was not required. Access to the database was granted by Optum under license.

Study Design

A retrospective new user cohort design was used. Patients were classified into mutually exclusive cohorts based on the first biologic initiated on or after 1 July 2016, to ensure that all treatment options of interest (i.e., ustekinumab, secukinumab, adalimumab, or ixekizumab) were available on the market. The index date was the date of biologic initiation. The baseline period was the 12-month period with continuous health plan eligibility prior to the index date. The follow-up period spanned from the index date to either end of data availability or end of continuous health plan eligibility, whichever was earlier.

Study Sample

Patients were included in the study if they met the following criteria: (1) two or more claims with a diagnosis of psoriasis [International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code: 696.1; ICD-10-CM codes: L40.0-L40.4, L40.8, L40.9] during the most recent period of continuous eligibility with one or more claim during the baseline period or on the index date; (2) initiated ustekinumab, secukinumab, adalimumab, or ixekizumab on or after 1 July 2016; (3) ≥ 12 months of continuous health plan eligibility before the index date; and (4) ≥ 18 years of age on the index date.

Patients were excluded from the study if they met any of the following criteria: (1) initiated multiple index agents on the index date, or (2) ≥ 1 claim for the index agent any time before the index date during the most recent period of continuous eligibility.

Study Outcomes

Discontinuation of an index biologic was defined as a therapy exposure gap in consecutive days of index agent supply, or between the last day of supply and the end of the follow-up period. To account for differences in dosing schedules among biologics, two definitions of therapy exposure gap based on the frequency of drug administration after the induction phase, as instructed per label (ustekinumab, 12 weeks [23]; secukinumab, 4 weeks [25]; adalimumab, 2 weeks [26]; ixekizumab, 4 weeks)[27] were considered in the main analysis. The first definition was based on a therapy exposure gap of more than one time the frequency of administration (i.e., ustekinumab, > 90 days; secukinumab, > 30 days; adalimumab, > 15 days; ixekizumab, > 30 days), the second based on the absence of a gap of more than twice the frequency of administration (i.e., ustekinumab, > 180 days; secukinumab, > 60 days; adalimumab, > 30 days; ixekizumab, > 60 days). The third definition of discontinuation considered was based on the absence of a therapy exposure gap of > 90 days for all biologics, and was used for a sensitivity analysis.

Adherence to the index biologic was described using the proportion of days covered (PDC). PDC was defined as the sum of non-overlapping days of supply of the index agent divided by a fixed period (i.e., 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months) among patients followed for at least the same fixed duration of time.

Switching and re-initiation patterns were also described. Switching from the index agent was defined as a claim for a new psoriasis treatment, such that the supply of the new treatment ended after the discontinuation of the index agent. Time to treatment switch was defined as the later of the date of the first claim for a new psoriasis treatment or the last day of supply of the index agent. Re-initiation of the index agent was defined as a new claim for the index agent after treatment discontinuation.

For all control cohorts, days of supply for medical claims were imputed on the basis of the frequency of biologic administration after induction, as per label [25,26,27]. For the ustekinumab cohort, days of supply for medical claims were imputed as 28 days of supply for the first claim and 84 days of supply for all second or later claims [23]. For the second or later ustekinumab pharmacy claims with days of supply between 28 and 34, days of supply were imputed to 84 as per label [23].

Statistical Analysis

Owing to the non-experimental nature of the study, entropy balancing (e-balance) was used to control for potential confounders between the ustekinumab cohort and the control cohorts. Each control cohort was reweighted so that the overall distribution of potential confounders in the reweighted cohorts had the same mean and variance (for continuous variables) or proportions (for binary variables) as the ustekinumab cohort. E-balance preserved the original sample size for all cohorts and enforced reweighted units to achieve balance while keeping the weights as close as possible to the base weights [28]. Cohorts were balanced on the following variables: demographics (i.e., age at index date, sex, region, type of insurance plan), year of index date, baseline all-cause total healthcare costs, Quan–Charlson comorbidity index (Quan–CCI) [29], psoriasis-related conditions (i.e., anxiety, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, depression, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, hypothyroidism, obesity, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, peripheral vascular disease, metabolic syndrome), other conditions requiring treatment with index therapies (i.e., ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis), smoking status, and use of systemic therapy, biologics, topical therapies, and opioids. The balance of baseline characteristics was assessed using standardized differences, with < 10% considered well balanced.

Kaplan–Meier (KM) survival analysis was used to describe the proportion of patients who discontinued their index agent at various points of follow-up, and median time to discontinuation was reported. Discontinuation rates were compared at 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months of follow-up using log-rank tests. Cox proportional hazard models were used to compare the risk of discontinuation between cohorts. Adherence, switching, and re-initiation patterns were described using means, standard deviations, and medians for continuous variables, and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

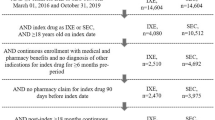

A total of 2230 patients were included in the ustekinumab cohort, 1807 in the secukinumab cohort, 4483 in the adalimumab cohort, and 535 in the ixekizumab cohort (Fig. 1). Across the unmatched study cohorts, mean age ranged from 49.0 to 53.3 years, 44.1–49.8% were female, 77.2–85.7% had a commercial insurance plan, and 76.2–83.9% had one or more psoriasis-related condition during the baseline period (Table S1). E-balance resulted in well-balanced patient characteristics across the study cohorts (Table 1). After e-balance, across all cohorts mean age was 49.0 years, 49.3% of patients were female, 85.7% had a commercial insurance plan, and 76.2–76.3% had one or more psoriasis-related condition during the baseline period. The proportion of biologic-experienced patients was 28.6% in all balanced cohorts. Mean total all-cause pharmacy costs ranged between $11,561 and $11,567 annually across balanced cohorts and mean total all-cause medical costs ranged between $10,767 and $10,772.

Patient selection. ICD-9-CM International Classification of Disease, 9th revision, Clinical Modification, ICD-10-CM International Classification of Disease, 10th revision, Clinical Modification. (1) Diagnoses of psoriasis were identified as ICD-9-CM code 696.1 and ICD-10-CM codes L40.0-L40.4, L40.8, and L40.9

Ustekinumab versus Secukinumab

Treatment Discontinuation

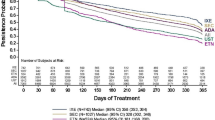

The mean duration of follow-up was 15.5 months in the ustekinumab cohort and 15.1 months in the secukinumab cohort. Using the exposure gap of more than one time the per-label frequency of administration to define discontinuation, median time to discontinuation was 13.3 months for the ustekinumab cohort and 7.6 months for the secukinumab cohort. The KM rates of discontinuation were lower for the ustekinumab cohort at 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months (all p < 0.001; Fig. 2A). Over the entire duration of available follow-up, patients in the ustekinumab cohort had a 46.4% lower risk of discontinuation compared with those in the secukinumab cohort (p < 0.001; Fig. 3).

Kaplan–Meier rates of treatment discontinuation among patients initiating on ustekinumab versus secukinumab based on duration of therapy exposure gap1,2. (A) Therapy exposure gap more than one time the labeled frequency of drug administration3. (B) Therapy exposure gap more than two times the labeled frequency of drug administration5. (C) Therapy exposure gap more than 90 days. HCPCS Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System, KM Kaplan–Meier, NDC National Drug Code, Quan–CCI Quan–Charlson Comorbidity Index. (1) Results are presented for balanced cohorts. (2) Discontinuation of the index therapy was defined as the presence of a therapy exposure gap between consecutive days of index therapy supply or the last day of supply and the end of the follow-up period. (3) One time therapy exposure gap is defined as time between administrations greater than or equal to the labeled maintenance dosing interval after induction of each index therapy, i.e., ustekinumab, > 12 weeks (90 days) × 1; secukinumab, > 4 weeks (30 days) × 1. (4) Refers to the population at risk of having the event at that point in time (i.e., patients who have not had the event and have not been lost to follow-up). (5) Two times therapy exposure gap is defined as the time between administrations greater than or equal to twice the labeled maintenance dosing interval after induction of each index therapy, i.e., ustekinumab, > 12 weeks (90 days) × 2; secukinumab, > 4 weeks (30 days) × 2

Risk of treatment discontinuation among patients in the ustekinumab versus secukinumab cohorts1. CI confidence interval, HCPCS Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System, HR hazard ratio, NDC National Drug Code, Quan–CCI Quan–Charlson Comorbidity Index. (1) Cox proportional hazard models were used to compare risk of discontinuation between balanced cohorts. (2) Discontinuation of the index therapy was defined as the presence of a therapy exposure gap between consecutive days of index therapy supply or the last day of supply and the end of the follow-up period. (3) One time therapy exposure gap is defined as time between administrations greater than or equal to the labeled maintenance dosing interval after induction of each index therapy, i.e., ustekinumab, > 12 weeks (90 days) × 1; secukinumab, > 4 weeks (30 days) × 1. (4) Two times therapy exposure gap is defined as the time between administrations greater than or equal to twice the labeled maintenance dosing interval after induction of each index therapy, i.e., ustekinumab, > 12 weeks (90 days) × 2; secukinumab, > 4 weeks (30 days) × 2

Using the exposure gap of more than two times the per-label frequency of administration to define discontinuation, median time to discontinuation was not reached for the ustekinumab cohort and was 12.0 months for the secukinumab cohort. The KM rates of discontinuation were lower for the ustekinumab cohort at 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months (all p < 0.001; Fig. 2B). Over the entire duration of available follow-up, patients who initiated ustekinumab had a 50.5% lower risk of discontinuation than those who initiated secukinumab (p < 0.001; Fig. 3).

Using the exposure gap of > 90 days for both cohorts to define discontinuation (sensitivity analysis), the median time to discontinuation was 15.5 months for the ustekinumab cohort and 15.1 months for the secukinumab cohort. KM rates of discontinuation were similar between cohorts (Fig. 2C), and no significant difference was observed in the risk of treatment discontinuation over the entire duration of available follow-up (Fig. 3).

Adherence

The mean PDC for ustekinumab and secukinumab was similar at 3 (0.78 and 0.76), 6 (0.76 and 0.72), 12 (0.69 and 0.65), 18 (0.63 and 0.57), and 24 (0.58 and 0.53) months of follow-up, with the PDC for ustekinumab trending higher. The proportion of patients with a PDC ≥ 0.8 appeared higher in the ustekinumab cohort at 3 and 6 months of follow-up as well as at 12, 18, and 24 months of follow-up (Fig. 4).

Proportion of patients with PDC for index biologic of ≥ 80%1. PDC proportion of days covered. (1) PDC was defined as the sum of non-overlapping days of supply of index therapy divided by a fixed period (i.e., 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months) among patients followed for at least the same fixed duration of time

Switching and re-initiation

Within the first 24 months of follow-up, based on the discontinuation gap of more than one time the per-label frequency of administration, 28.2% and 40.5% of patients in the ustekinumab and secukinumab cohorts switched to a new psoriasis-related treatment (mean time to switch 9.1 and 8.3 months, respectively). The most common therapies to which patients switched were topical agents (51.8% and 65.1%), followed by another biologic (33.7% and 17.6%). Among those who discontinued their index therapy (43.8% and 62.6%), it was re-initiated by 28.2% and 49.5% of patients after a mean of 5.3 and 2.7 months, respectively.

Ustekinumab versus Other Biologics (Adalimumab and Ixekizumab)

Treatment Discontinuation

The mean available follow-up time was 15.4 months for the adalimumab cohort and 15.1 months for the ixekizumab cohort. Using the exposure gap of more than one time the per-label frequency of administration to define discontinuation, median time to discontinuation was 13.3 months for the ustekinumab cohort, 4.8 months for the adalimumab cohort, and 5.7 months for the ixekizumab cohort. The KM rates of discontinuation were lower for the ustekinumab cohort relative to both the adalimumab and ixekizumab cohorts at 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months (all p < 0.001; Fig. S1). Over the entire duration of available follow-up, patients who initiated ustekinumab had a 62.2% lower risk of discontinuation relative to those who initiated adalimumab, and a 43.8% lower risk of discontinuation compared with those who initiated ixekizumab (Fig. 5).

Risk of treatment discontinuation among patients in the ustekinumab versus adalimumab or ixekizumab cohorts1. CI confidence interval, HCPCS Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System, HR hazard ratio, NDC National Drug Code, Quan–CCI Quan–Charlson Comorbidity Index. (1) Cox proportional hazard models were used to compare risk of discontinuation between balanced cohorts. (2) Discontinuation of the index therapy was defined as the presence of a therapy exposure gap between consecutive days of index therapy supply or the last day of supply and the end of the follow-up period. (3) One time therapy exposure gap is defined as time between administrations greater than or equal to the labeled maintenance dosing interval after induction of each index therapy, i.e., ustekinumab, > 12 weeks (90 days) × 1; secukinumab, > 4 weeks (30 days) × 1; adalimumab, > 2 weeks (15 days) × 1; ixekizumab, > 4 weeks (30 days) × 1. (2) Two times therapy exposure gap is defined as the time between administrations greater than or equal to twice the labeled maintenance dosing interval after induction of each index therapy, i.e., ustekinumab, > 12 weeks (90 days) × 2; secukinumab, > 4 weeks (30 days) × 2; adalimumab, > 2 weeks (15 days) × 2; ixekizumab, > 4 weeks (30 days) × 2

Using the exposure gap of more than two times the per-label frequency of administration to define discontinuation, median time to discontinuation was not reached for the ustekinumab cohort and was 7.3 months and 12.1 months for the adalimumab and ixekizumab cohorts, respectively. Relative to the adalimumab and ixekizumab cohorts, KM rates of discontinuation were lower for the ustekinumab cohort at 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months (all p < 0.001). Over the entire duration of available follow-up, patients who initiated ustekinumab had a 66.4% lower risk of discontinuation relative to those who initiated adalimumab, and a 46.5% lower risk of discontinuation compared with those who initiated ixekizumab (all p < 0.001) (Fig. 5).

Using the therapy exposure gap of > 90 days for all cohorts to define discontinuation (sensitivity analysis), the median time to discontinuation was 13.3 months for the ustekinumab cohort, 11.8 months for the adalimumab cohort, and 24.1 months for the ixekizumab cohort. Over the entire duration of available follow-up, there were no significant differences in the risk of discontinuation between patients in the ustekinumab cohort relative to those in the other control cohorts (Fig. 5).

Adherence

The mean PDC for ustekinumab, adalimumab and ixekizumab was similar at 3 (0.78, 0.81, and 0.80), 6 (0.76, 0.73, and 0.70), 12 (0.69, 0.61, and 0.60), 18 (0.63, 0.52, and 0.55), and 24 (0.58, 0.47, and 0.56) months of follow-up, with the PDC for ustekinumab trending higher over time. The proportion of patients with a PDC ≥ 0.8 appeared higher in the ustekinumab cohort compared with the adalimumab and ixekizumab cohorts at 6, 12, and 18 months of follow-up (Fig. 4).

Switching and Re-initiation

Within the first 24 months of follow-up, based on the discontinuation gap of more than one time the per-label frequency of administration, 28.2%, 47.2%, and 35.9% of patients in the ustekinumab, adalimumab, and ixekizumab cohorts switched to a new psoriasis-related treatment (mean time to switch 9.1, 7.1, and 8.0 months, respectively). The most common therapies to which patients switched were topical agents (51.8%, 60.1%, and 59.0%), followed by another biologic (33.7%, 24.1%, and 18.4%). Among those who discontinued their index therapy (43.8%, 71.8%, and 60.8%), it was re-initiated by 28.2%, 56.0%, and 52.6% of patients after a mean time of 5.3, 1.5, and 2.5 months, respectively.

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study examined treatment discontinuation, and described adherence and switching patterns associated with various biologics used to treat moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Based on a therapy exposure gap equivalent to one or two times the per-label frequency of drug administration, ustekinumab was associated with significantly lower rates of treatment discontinuation compared with secukinumab, adalimumab, and ixekizumab. In a conservative sensitivity analysis, in which treatment discontinuation was defined as a 90-day exposure gap, rates of treatment discontinuation were similar between ustekinumab and other study biologics.

The current study builds on prior evidence by further documenting the benefits of ustekinumab with respect to treatment persistence. Although several previous US studies have found ustekinumab to be associated with the lowest risk of treatment discontinuation compared with older biologics (i.e., etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab) [8, 10, 21], only Wu et al. analyzed more recent data including users of IL-17A antagonists [21]. The analyses conducted by Wu et al. were descriptive in nature, but the numerical trends observed are consistent with those of the current study, and suggest that ustekinumab is associated with lower rates of discontinuation than other biologics, including IL-17A antagonists. Similar to the present study, Wu et al. did not observe any differences between ustekinumab and other biologics in rates of treatment discontinuation, when defined by a fixed gap of > 90 days. It is important to point out that this conservative definition of treatment discontinuation likely disfavors biologics that are administered less frequently, such as ustekinumab.

Reasons for biologic discontinuation were not available in this study. Different dosing schedules of ustekinumab relative to secukinumab, adalimumab, and ixekizumab may have influenced the different discontinuation rates observed across the biologics. At the same time, the convenience and schedule of administration should have been explained to a patient when informed consent was obtained to initiate a specific biologic. Other causes of discontinuation could include diminished therapeutic effect or toxicity [18], but clinical information on treatment effectiveness and safety was not available in the data.

The analysis of adherence in this study was descriptive in nature, and the observed trends conservatively suggest non-inferiority of ustekinumab relative to other study biologics. Similar trends were observed in most [8, 20, 21], albeit not all [19], prior studies conducted in the USA that compared adherence with ustekinumab versus older biologics. In particular, the adherence rates over the 12-month follow-up period observed in the current study were generally consistent with those reported by Wu et al. for adalimumab (current study, 37.3%; Wu et al., 35.6%), secukinumab (current study, 43.6%; Wu et al., 41.7%), and ustekinumab (current study, 45.3%; Wu et al., 50.6%) [21].

Permanent or temporary treatment discontinuation is frequent among patients with psoriasis who initiate biologics [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15], which may lead to poorer health outcomes. The preponderance of available data suggests that continuous biologic treatment is associated with better disease control than intermittent treatment [16, 17]. In the EXPRESS2 study, patients randomized to the continuous infliximab arm achieved better Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) responses than those randomized to the as-needed infliximab arm (i.e., infliximab administered only if PASI improvement was < 75%) [30]. In the SCULPTURE trial, more patients on a secukinumab fixed interval regimen maintained PASI 75, i.e., ≥ 75% improvement from baseline PASI score versus the study specified retreatment-as-needed regimen [31]. Therefore, the data from the current study may inform optimizing choice of biologic therapy to minimize the risk of treatment discontinuation and associated suboptimal outcomes for disease control and quality of life. Of note, previous studies have demonstrated that dose reduction of biologic therapies, also known as dose tapering, achieved either by increasing the interval between doses or by reducing the dosage, in well-controlled patients results in similar efficacy and safety as standard dosing and does not shorten drug survival [32, 33].

The present study has several strengths. To the best of our knowledge, it included the largest sample of patients with psoriasis initiating IL-17A antagonists (i.e., secukinumab or ixekizumab) to date. Furthermore, this study covers the period after the approval of ustekinumab self-administration in the USA (i.e., before 21 May 2013, ustekinumab could only be administered by a healthcare provider during office visits) [22, 23]. Since the option of self-administration may have a significant impact on discontinuation and adherence [24], the data in this study may more accurately reflect contemporary real-world treatment patterns. In addition, treatment discontinuation was evaluated through up to 36 months of follow-up, providing information on more long-term trends. Lastly, e-balance was used to control for observed differences in patient baseline characteristics. In contrast to more traditional balancing techniques such as matching, this relatively new technique offers the advantage of retaining the full original sample size in addition to controlling for an exhaustive list of covariates.

Nonetheless, the results of the current study should be interpreted with consideration of some limitations. First, study outcomes were evaluated in a population of commercially insured and Medicare Advantage beneficiaries in the USA; thus, results may not be generalized to the uninsured or patients with other types of health insurance (e.g., Medicaid). Second, as in all observational studies, the impact of unobserved confounders cannot be ruled out. For example, e-balance did not directly control for disease duration or psoriasis severity as these data are not available in health insurance claims. Nonetheless, e-balance accounted for other covariates that may serve as a proxy for disease severity, such as prior biologic exposure and opioid use, which may help mitigate the potential impact of this limitation. Third, reasons for biologic discontinuation or clinical information that could allow to infer them [e.g., PASI score, kinetics and safety data] were not available in the database and could not be explored. Relatedly, since efficacy and safety outcomes were not measured in this study, it is unknown whether treatment discontinuation was related to diminishing treatment effect, adverse events, or other safety issues. Fourth, newer biologics like the IL-23p19 inhibitors guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab were not included in this study since they were only approved near the end of the study period and were thus infrequently used in the data cut.

Conclusion

In this retrospective cohort study, patients initiating ustekinumab had a lower risk of treatment discontinuation and showed a numerical trend toward higher adherence relative to those initiating other biologics, including IL-17A antagonists. These results may help inform the choice of biologic therapy based on compliance, which may subsequently improve outcomes of patients with psoriasis.

Change history

06 April 2022

Under Key Summary Points, the text in first and last paragraph removed.

References

Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(3):512–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.013 (PubMed PMID: 24388724).

Dalgard FJ, Gieler U, Tomas-Aragones L, et al. The psychological burden of skin diseases: a cross-sectional multicenter study among dermatological out-patients in 13 European countries. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(4):984–91. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2014.530 (PubMed PMID: 25521458; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4378256).

Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(4):1029–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057 (PubMed PMID: 30772098).

Strohal R, Kirby B, Puig L, et al. Psoriasis beyond the skin: an expert group consensus on the management of psoriatic arthritis and common co-morbidities in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(12):1661–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.12350 (PubMed PMID: 24372845; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4258087).

Pirro M, Stingeni L, Vaudo G, et al. Systemic inflammation and imbalance between endothelial injury and repair in patients with psoriasis are associated with preclinical atherosclerosis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22(8):1027–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487314538858 (PubMed PMID: 24906366).

Shaw MK, Davis SA, Feldman SR, et al. Trends in systemic psoriasis treatment therapies from 1993 through 2010. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13(8):917–20 (PubMed PMID: 25116968).

Amin M, No DJ, Egeberg A, et al. Choosing first-line biologic treatment for moderate-to-severe psoriasis: what does the evidence say? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-017-0328-3 (PubMed PMID: 29080066).

Doshi JA, Takeshita J, Pinto L, et al. Biologic therapy adherence, discontinuation, switching, and restarting among patients with psoriasis in the US Medicare population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(6):1057–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2016.01.048 (e4; PubMed PMID: 26946986; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4945117).

Feldman SR, Pelletier CL, Wilson KL, et al. Real-world US healthcare costs of psoriasis for biologic-naive patients initiating apremilast or biologics. J Comp Eff Res. 2019;8(1):45–54. https://doi.org/10.2217/cer-2018-0097 (PubMed PMID: 30387367).

Feldman SR, Zhao Y, Navaratnam P, et al. Patterns of medication utilization and costs associated with the use of etanercept, adalimumab, and ustekinumab in the management of moderate-to-severe psoriasis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(3):201–9. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.3.201 (PubMed PMID: 25726029).

Higa S, Devine B, Patel V, et al. Psoriasis treatment patterns: a retrospective claims study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(10):1727–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2019.1618805 (PubMed PMID: 31081697).

Lee S, Xie L, Wang Y, et al. Evaluating the effect of treatment persistence on the economic burden of moderate to severe psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis patients in the U.S. Department of Defense Population. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(7):654–63. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2018.24.7.654 (PubMed PMID: 29952710).

Murage MJ, Anderson A, Casso D, et al. Treatment patterns, adherence, and persistence among psoriasis patients treated with biologics in a real-world setting, overall and by disease severity. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30(2):141–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546634.2018.1479725 (PubMed PMID: 29799292).

Svedbom A, Dalen J, Mamolo C, et al. Treatment patterns with topicals, traditional systemics and biologics in psoriasis—a Swedish database analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(2):215–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.12494 (PubMed PMID: 24813476).

Thorneloe RJ, Bundy C, Griffiths CE, et al. Adherence to medication in patients with psoriasis: a systematic literature review. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(1):20–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.12039 (PubMed PMID: 22963128).

Brezinski EA, Armstrong AW. Off-label biologic regimens in psoriasis: a systematic review of efficacy and safety of dose escalation, reduction, and interrupted biologic therapy. PLoS One. 2012;7(4): e33486. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0033486 (PubMed PMID: 22509259; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3324468).

Reich K, Wozel G, Zheng H, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab as continuous or intermittent therapy in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results of a randomized, long-term extension trial (RESTORE2). Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(6):1325–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.12404 (PubMed PMID: 23621698).

Yeung H, Wan J, Van Voorhees AS, et al. Patient-reported reasons for the discontinuation of commonly used treatments for moderate to severe psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(1):64–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2012.06.035 (PubMed PMID: 22846688; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3488143).

Feldman SR, Zhang J, Martinez DJ, et al. Real-world treatment patterns and healthcare costs of biologics and apremilast among patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis by metabolic condition status. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;8:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546634.2019.1698699 (PubMed PMID: 31769703).

Goren A, Carter C, Lee S. Patient reported health outcomes and non-adherence in psoriasis patients receiving adalimumab or ustekinumab for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27(1):43–50. https://doi.org/10.3109/09546634.2015.1049972 (PubMed PMID: 26088404).

Wu B, Muser E, Teeple A, et al. Treatment adherence and persistence of five commonly prescribed medications for moderate to severe psoriasis in a U.S. commercially insured population. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;8:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546634.2019.1687828 (PubMed PMID: 31714168).

US Food and Drug Administration. STELARA (ustekinumab) - Prescribing Information (Revised 04/2013). Available from: Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/125261s099lbl.pdf

US Food and Drug Administration. STELARA (ustekinumab) - Prescribing Information (Revised 12/2020). Available from: Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/125261s154,761044s006lbl.pdf

Muzumdar S, Waldman R, Wu R, et al. In-office administration associated with increased drug survival of ustekinumab for chronic plaque psoriasis when compared with self-administration: a single institution retrospective chart review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2019.10.041 (PubMed PMID: 31669440).

US Food and Drug Administration. COSENTYX (secukinumab)—Prescribing Information. Available from: Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/125504s035lbl.pdf

US Food and Drug Administration. HUMIRA (adalimumab)—Prescribing Information. Available from: Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/125057s418s419lbl.pdf

US Food and Drug Administration. TALTZ (ixekizumab)—Prescribing Information. Available from: Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/125521s019lbl.pdf

Hainmueller J. Entropy balancing for causal effects: a multivariate reweighting method to produce balanced samples in observational studies. Polit Anal. 2012;20:25–46.

Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–9.

Menter A, Feldman SR, Weinstein GD, et al. A randomized comparison of continuous vs. intermittent infliximab maintenance regimens over 1 year in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(1):31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2006.07.017 (e1–15; PubMed PMID: 17097378).

Mrowietz U, Leonardi C, Girolomoni G, et al. Secukinumab retreatment-as-needed versus fixed-interval maintenance regimen for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, noninferiority trial (SCULPTURE). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(1):27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2015.04.011.

Hansel K, Bianchi L, Lanza F, et al. Adalimumab dose tapering in psoriasis: predictive factors for maintenance of complete clearance. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97(3):346–50. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-2571 (PubMed PMID: 27868145).

Llamas-Velasco M, Dauden E. Reduced doses of biological therapies in psoriasis may increase efficiency without decreasing drug survival. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6): e14134. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.14134 (PubMed PMID: 32761730).

Acknowledgements

Funding

This work, including medical writing assistance and payment of the journal’s Rapid Service Fee, was supported by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. The study sponsor was involved in several aspects of the research, including the study design, the interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Dominic Pilon, Maryia Zhdanava, Laura Morrison, Aditi Shah, and Patrick Lefebvre contributed to study conception and design, collection and assembly of data, and data analysis and interpretation. Timothy Fitzgerald and Amanda Teeple contributed to study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation. All authors reviewed and approved the final content of this manuscript.

Previous Presentations

Part of the material in this manuscript was presented at the American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting as a poster presentation with interim findings. The poster’s abstract was published in “Poster Abstracts” in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Volume 85, Issue 3, Supplement AB15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.086.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Medical writing assistance was provided by Samuel Rochette, who is an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., a company that provided consulting services to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. for the conduct of this study.

Disclosures

Dominic Pilon, Maryia Zhdanava, Laura Morrison, Aditi Shah, and Patrick Lefebvre are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a company which provided consulting services to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. for the conduct of this study. Timothy Fitzgerald and Amanda Teeple are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. and may own stocks or stock options.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All data were de-identified and complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act; therefore, institutional review board approval was not required. Access to the database was granted by Optum under license.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Optum, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Any researchers interested in obtaining the data used in this study can access the database through Optum, under a license agreement, including the payment of appropriate license fee.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pilon, D., Fitzgerald, T., Zhdanava, M. et al. Risk of Treatment Discontinuation among Patients with Psoriasis Initiated on Ustekinumab and Other Biologics in the USA. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 12, 971–987 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-022-00707-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-022-00707-z