Abstract

Introduction

Dupilumab is a biologic therapy approved for treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD). Our objective was to assess the real-world effectiveness, safety and laboratory monitoring practices for dupilumab in a tertiary centre.

Methods

A retrospective review of medical records of all patients receiving dupilumab between September 2017 and October 2019 was undertaken. Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) were collected at weeks 0, 12–16 and 26–30. Data on laboratory tests undertaken for dupilumab screening and monitoring were also collected.

Results

At 12–16 weeks, 58.9% and 37.3% of patients achieved ≥ EASI 75 and ≥ EASI 90, respectively (n = 156). Ninety-four patients underwent further analysis at weeks 26–30 with those achieving ≥ EASI 75 increasing from 61.7% (12–16 weeks) to 75.31%, and EASI 90 increasing from 35.8% (12–16 weeks) to 49.8%. The most common side effects were eye symptoms occurring in 43.1% of patients, with 16.3% developing conjunctivitis. The mean treatment duration was 255 days, during which an average of three sets of blood tests were performed (n = 149). Of all laboratory abnormalities recorded, 24% started after initiation of dupilumab, and 93% were classified as ‘mild’. Dupilumab was not documented as causative in any of the cases, nor was treatment stopped on account of laboratory abnormalities.

Conclusion

Dupilumab provides an effective and safe treatment option for patients with AD. Clinical response continued to improve past 16 weeks in this real-world population. No laboratory abnormalities were felt to be secondary to dupilumab; screening and monitoring tests did not influence dupilumab prescribing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Dupilumab has been shown to be an effective treatment in large double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trials and smaller real-world studies. |

This study presents a tertiary centre experience on dupilumab effectiveness, safety and tolerability in a cohort of 164 patients followed over 12–30 weeks. |

This is the first real-world study to evaluate the laboratory safety of dupilumab. |

What was learned from the study? |

This study showed that dupilumab is an effective and safe treatment for patients with atopic dermatitis. |

Clinical response continues to improve past 16 weeks. |

No detected laboratory abnormalities secondary to dupilumab. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features to facilitate understanding of the article. You can access the digital features on the article’s associated Figshare page. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13187441.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic relapsing, remitting inflammatory dermatosis characterised by xerosis, skin inflammation and intense pruritus [1]. The lifetime prevalence is estimated between 10–20% in children and 2–10% in adults worldwide [2, 3]. The pathogenesis is not fully understood, but involves a complex interplay between skin barrier dysfunction, environmental factors, infectious agents and immune dysregulation [4]. These interactions potentiate a T-cell response with a marked increase in the expression of T helper (Th) 2 cytokines in the acute phase and Th1, Th17 and Th22 cytokines in the chronic phase [5]. Interleukins (IL)-4 and IL-13 are predominantly produced by Th2 lymphocytes and are pivotal cytokines in the pathogenesis of AD [6]. They enhance inflammation, induce pruritus, disrupt the epidermal barrier and increase susceptibility to infection [7].

Mild disease is usually managed with topical corticosteroids (TCSs) and calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs), in addition to regular emollients. However, moderate to severe disease often requires phototherapy or treatment with systemic immuno-suppressive therapies [8]. Traditional systemic treatments, including systemic corticosteroids, ciclosporin A, methotrexate and azathioprine, may suffer from limited efficacy and an adverse side-effect profile; as such, patient treatment options are often limited [9].

Dupilumab is the first monoclonal antibody approved for the treatment of moderate to severe AD [10]. It targets the alpha subunit of the IL-4 receptor, thereby down-regulating the activity of IL-4 and IL-13 signalling of Th2 T-cell differentiation [11]. The efficacy and safety of Dupilumab has been demonstrated in a number of key randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III clinical trials. In SOLO 1 and SOLO 2, Dupilumab was examined as a monotherapy, whilst in CHRONOS and CAFÉ it was tested in combination with topical corticosteroids [12,13,14]. In the EU, dupilumab is an approved treatment for patients aged ≥ 12 years with moderate-to-severe AD who are suitable for systemic therapy [15]. In the USA, dupilumab is approved to treat patients aged ≥ 12 years who have moderate-to-severe AD whose disease is not adequately controlled and/or suitable for topical therapies [16].

In contrast to biologic therapies used in the treatment of psoriasis, the Dupilumab summary of product characteristics (SPC) does not advocate routine laboratory screening or monitoring tests [17]. However, as with all novel therapies, ‘real-world’ data to support this view is lacking. It is likely that wide variability in testing exists both within and between dermatology centres. Moreover, clinical trial cohorts are often far from representative of real-world populations given their strict inclusion and exclusion criteria which may have further implications on the need for laboratory monitoring [18, 19].

The aims of this study were to: (a) evaluate the real-world effectiveness and safety profile of dupilumab, (b) summarise our centre’s practice of laboratory screening and monitoring of dupilumab-treated patients and (c) establish whether laboratory abnormalities were felt to be secondary to dupilumab.

Methods

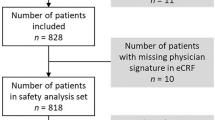

A retrospective, electronic case-note review was undertaken for all adult patients receiving dupilumab at Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust from September 2017 to October 2019; a large, tertiary Dermatology referral centre serving a population of 240,000. All patients with moderate to severe AD, aged ≥ 18 years, were prescribed dupilumab in accordance with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines. All patients received the manufacturer’s standard dose (600 mg at initiation, followed by 300 mg every other week by subcutaneous injection). Patients were encouraged to use concomitant emollients and TCSs or TCIs as required. Baseline demographic data on age, gender, comorbidities and previous systemic AD treatments were collected. Clinical response was assessed using the Eczema Area and severity Index (EASI, 0–72) and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI, 0–30) at weeks 12–16 and approximately 6 months [20, 21]. Data on adverse events and laboratory test (screening and monitoring) abnormalities were recorded.

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

In total, 164 patients, 98 male and 66 female, met the inclusion criteria for both parts of the study (Table 1). The median age was 36 years (range 18–87 years). All patients had failed at least one systemic treatment (mean 4.78, range 1–9) prior to dupilumab with ciclosporin being the most commonly prescribed systemic treatment. A total of 83.53% had a history of other atopic diatheses.

Dupilumab Effectiveness and Adverse Events

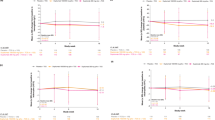

Analysis at 12–16 weeks (Fig. 1) included 156 patients with a baseline EASI of 23 ± 16 [median ± interquartile range (IQR)] and DLQI of 22 ± 10 (eight patients had not reached this time point). The median EASI and DLQI scores dropped to 4 ± 8.4 and 4 ± 9, respectively, at 12–16 weeks. EASI-75 and EASI-90 were achieved by 58.96% and 37.31% of patients, respectively (Fig. 2a). Of the 156 patients, 94 patients with a baseline median EASI of 23 ± 16 and DLQI of 21 ± 11 completed their second review and underwent analysis at 26–30 weeks. Their median EASI and DLQI scores at 12–16 weeks were 3.2 ± 7 and 3 ± 7, respectively, and at 26–30 weeks were 2 ± 4 and 2 ± 7, respectively. At weeks 12–16, 61.73% of the patients achieved ≥ EASI-75, which increased to 75.31% at weeks 26–30. At weeks 12–16, 35.80% achieved ≥ EASI 90 increasing to 49.83% at weeks 26–30 (Fig. 2b).

The most commonly reported side effects (Table 2) were eye symptoms occurring in 42.30% (66/156) of patients. Of those, 23.07% (36/156) patients had mild eye symptoms manifesting as dry, itchy and/or gritty eye, 16.02% (25/156) had conjunctivitis, 1.92% (3/156) had episcleritis, 0.64% (1/156) had worsening of pre-existing blepharitis, and 0.64% (1/156) had bacterial conjunctivitis. In our cohort, 6.41% (10/156) were noted to have persistent facial erythema. Within the first 16 weeks of treatment, 3.84% (6/156) of patients developed arthralgia. One patient had localised arthralgia to knees and hips, while five patients had generalised arthralgia which self-resolved in one patient. The remainder were referred to rheumatology for further evaluation and remain undiagnosed. The arthralgia had not resolved during the period of study follow-up. None of these patients discontinued treatment as a consequence of their symptoms given the ongoing beneficial effect of dupilumab on their skin. Alopecia areata (AA) occurred in 3.20% of patients (5/156) while on dupilumab. One patient had stable pre-existing alopecia areata. Four patients developed new onset AA, two with patchy AA (one biopsy confirmed, suggestive of drug induced), one with diffuse AA, and one ophiasis pattern AA. In two patients, the alopecia completely resolved with continued dupilumab therapy, the patient with biopsy-confirmed AA remained on treatment at their request. One patient chose to stop dupilumab and had hair regrowth within 3 months of cessation.

Overall, 7.69% (12/156) of patients stopped treatment, 1.92% (3/153) on account of severe conjunctivitis at 12 (n = 2) and 26 weeks (n = 1). Of those, two patients were re-treated with conventional systemic immunosuppressants with good effect. One patient remains on topical therapies with sub-optimal control. In total, 1.23% (2/156) stopped dupilumab due to lack of efficacy at week 12, 0.64% (1/155) developed ophiasis pattern (AA), 0.64% (1/156) had a vasovagal episode after the first dupilumab injection and the patient declined further treatment, 0.64% (1/156) opted to stop treatment due to its mode of administration despite the positive benefit on their skin. These patients are now being managed with topical treatments with variable response. Overall, 1.28% (2/156) became pregnant with treatment cessation at 12 and 16 weeks. Of those, eczema remained clear in one patient but flared in the other, necessitating intensive topical treatments. Finally, 1.28% (2/156) were lost to follow-up at 12 (n = 1) and 26 (n = 1) weeks and treatment was discontinued.

Laboratory Screening and Monitoring

Of the 164 included patients, 149 (91%) had screening laboratory tests. The majority included a full blood count (FBC), urea and electrolytes (U&E), liver function tests (LFT), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) and virology screen. Monitoring blood tests were performed in 149 (91%) patients, which routinely included FBC, U&E, LFT and GGT. The mean length of time on treatment was 255 days (range 7–807 days), with a mean of three sets of monitoring blood tests performed per patient (range 0–10). In total, 136 patients had abnormalities identified (Table 3). These most commonly included eosinophilia (n = 82), other FBC derangements such as anaemia (n = 53), U&E abnormalities (n = 55) or deranged LFTs (n = 67). Of these abnormalities, the majority (73%) were present prior to initiation of dupilumab. For those with onset post-dupilumab therapy, 93% were mild and 63% were transient (See table S1 in the electronic supplementary materials for severity criteria for laboratory abnormalities). Abnormal results were managed as follows: letter to patient’s primary care physician (n = 14), repeat or further blood tests (n = 13), referral to specialist (n = 1), no action deemed necessary (n = 113). While dupilumab was not documented as a cause of laboratory abnormalities in the medical records of any of the cases, a mild, transient eosinophilia was common and did appear to be temporally related to the initiation of dupilumab. Dupilumab was not stopped due to any laboratory abnormalities.

Discussion

In this retrospective observational study, dupilumab treatment was found to be an effective and well-tolerated treatment for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. The proportion of patients achieving 75% and 90% reduction in their EASI scores at 12–16 weeks were 58.96% and 37.31%, respectively. Our results are similar to phase III trials on efficacy of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids at 16 weeks (CHRONOS, EASI-75: 69% and CAFÉ, EASI-75: 62%). However, the afore-mentioned clinical trials used a non-responder imputation analysis, a more conservative form of analysis than the observed analysis used in this study [13, 14]. Moreover, our findings are compatible with other real-world studies. Aramario-Hita et al. [22] reported an EASI reduction of 79.3% in 70 patients at 24 weeks. Olesen et al. [23] reported an EASI-75 in 63.3% patients (19/30) at 3 months review. In a French multi-centre, retrospective cohort study, Faiz et al. [24] reviewed 241 patients with EASI score recorded in 82 patients of those, EASI ≥ 75 score was achieved in 48.8% of the patients (40/82) at 3 months review. In a prospective Dutch two-centre cohort study, de Wijs et al., studied 95 patients, of whom 43 were on concomitant systemic immunosuppressants. Their mean EASI score decreased from 18.6 to 7.3 at 16 weeks review [25]. In our study, EASI and DLQI scores continued to improve with continuation of treatment beyond 16 weeks.

In our cohort, 42.30% (66/156) presented with eye symptoms, of whom 16.02% (25/156) had conjunctivitis. All patients were encouraged to use lubricant eye ointment as a preventative measure throughout the treatment period. Conjunctivitis was reported in a range of 8.6–22.1% of the patients in dupilumab clinical trials [26] but in up to 65% in daily practice experience studies [22,23,24,25, 27,28,29,30]. The majority of our patients had mild-to-moderate eye disease which was treated with lubricants and/or steroids eye drops and did not require treatment interruption. The exact cause of dupilumab-induced conjunctivitis remains unknown, but recent evidence suggests that increasing severity of AD at baseline increases the risk of dupilumab associated eye disease [31, 32].

Ten patients developed paradoxical facial erythema with clearance of the eczema on the rest of their body. This was initially noted at patients’ first review (12–16 weeks). None of the patients stopped the treatment on account of this side effect given the beneficial effect of dupilumab on the rest of their skin. Patients were treated with TCSs and TCIs with variable responses. De Wijs et al. reported a case series of seven patients who developed paradoxical facial erythema while on dupilumab. Histological examination of lesional skin revealed a psoriasiform pattern in four of the patients. It is hypothesised that this might represent a cytokine shift towards a Th1 phenotype resulting in a psoriasiform inflammatory pattern [33]. Recently, there have been reports of biopsy proven psoriasiform rashes (erythrodermic psoriasis and classical plaque psoriasis) arising in patients treated with dupilumab for AD [34,35,36]. Prior work by Newcomb and colleagues, showed that IL4/IL13 antagonises IL17A, which might explain the psoriasiform features seen in patients on dupilumab [37].

Six patients reported arthralgia in our cohort. Arthralgia was reported in phase III clinical trials (0.8–4.5%) but the incidence was similar to the placebo group [13, 14]. Arthralgia has recently been added to the Summary of Product Characteristics for dupilumab as a result of post marketing reporting [15]. Willsmore et al. [38] reported a series of three patients who developed generalised seronegative arthritis and enthesitis during dupilumab treatment. The pathogenesis of arthralgia in these patients remains unclear. However, recent evidence suggests that IL-4 and IL-13 have been shown to selectively suppress IL-23 production with reduced Th17 function [39]. The authors hypothesised that dupilumab may induce an IL 17 induced peripheral spondyloarthopathy/psoriatic arthritis by inhibiting IL-4 and IL 13.

Five patients in our cohort developed AA-like hair loss. Flaring of pre-existing AA, new onset AA and improvement of AA have all been described in patients treated with dupilumab [40,41,42]. One of our patients with patchy alopecia areata had histology compatible with a mixed inflammatory pattern with psoriasiform and spongiotic elements. There were miniaturised hair follicles with marked sebaceous gland atrophy and perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate with occasional eosinophils. The features were suggestive of drug-induced alopecia. Zhu et al. described a similar histological pattern in one of their patients who developed AA-like hair loss while on dupilumab [43]. Sebaceous gland atrophy has been described in drug-induced AA-like reactions as well as other inflammatory skin diseases such as psoriasis, but it is not a histological feature of AA [44]. These histological features in addition to the variation in clinical presentation, are suggestive of dupilumab-induced alopecia rather than autoimmune alopecia areata.

Our data on laboratory screening and monitoring support the findings of the phase III clinical trials which suggest that dupilumab can be used without laboratory monitoring [45]. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study investigating the need for laboratory screening and monitoring in real-world patients, who are often under-represented in clinical trials.

Our study does have limitations; its retrospective nature was subject to recall bias and relies upon accurate, contemporaneous electronic record keeping. As with all ‘real-world’ studies some data were missing (approximately 12–15% at 3 or 6 month review) however, given the large number of patients included, we do not think this adversely impacted on our findings. EASI score was reported by multiple clinicians and may have been subject to inter-observer variation. Moreover, laboratory abnormalities may have been pre-existing, or represented fluctuations in persistently abnormal laboratory parameters, such as creatinine in patients with chronic kidney disease, rather than being attributable to dupilumab therapy, but this was difficult to ascertain. Finally, our study lacked a control arm of participants not receiving dupilumab, which would help in drawing statistical associations between dupilumab and laboratory abnormalities.

In summary, data from our real-world cohort showed that dupilumab provided an effective and well-tolerated treatment option to for patients with moderate to severe eczema. Our findings suggest that clinical response continues to improve past 16 weeks and, for this reason, we recommend continuation of treatment in partial or slow responders. These finding are concordant with a recent systematic review demonstrating dupilumab is a effective and safe treatment in adults with moderate–severe atopic dermatitis, with continued long-term benefit out to 52 weeks [46].

The incidence of dupilumab-induced eye symptoms and conjunctivitis was higher in our cohort compared with phase III clinical trials but, overall, only a small proportion of patients had to stop treatment due to severe conjunctivitis. Interesting paradoxical reactions including persistent facial erythema, arthralgia and drug-induced alopecia were observed in our cohort, which are highly suggestive of Th2 to Th1/Th17 phenotype switch. Other than a transient eosinophilia, no abnormal laboratory findings were attributed to dupilumab, supporting the position that blood monitoring in dupilumab patients may be unnecessary. This study provides additional support on the safety and effectiveness of dupilumab in the treatment of AD. It also highlights the importance of post-marketing reporting to identify previously unrecognised adverse reactions to newly approved medications. Further research is required to fully understand the cytokine-switch phenomenon seen with novel targeted therapies.

References

Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, Kabashima K, Irvine AD. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):1.

Deckers IA, McLean S, Linssen S, Mommers M, Van Schayck CP, Sheikh A. Investigating international time trends in the incidence and prevalence of atopic eczema 1990–2010: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e3980.

Odhiambo JA, Williams HC, Clayton TO, Robertson CF, Asher MI, ISAAC Phase Three Study Group. Global variation in prevalence of eczema symptoms in children from ISAAC Phase Three. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(6):1251-8.e23.

Silverberg JI, Hanifin JM. Adult eczema prevalence and associations with asthma and other health and demographic factors: a US population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(5):1132–8.

Boguniewicz M, Leung DY. Atopic dermatitis: a disease of altered skin barrier and immune dysregulation. Immunol Rev. 2011;242(1):233–46.

Gittler JK, Shemer A, Suárez-Fariñas M, Fuentes-Duculan J, Gulewicz KJ, Wang CQ, et al. Progressive activation of T(H)2/T(H)22 cytokines and selective epidermal proteins characterizes acute and chronic atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(6):1344–54.

Silverberg JI, Kantor R. The Role Of Interleukins 4 and/or 13 in the pathophysiology and treatment of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35(3):327–34.

Brunner PM, Guttman-Yassky E, Leung DYM. The immunology of atopic dermatitis and its reversibility with broad-spectrum and targeted therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:S65–76.

Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(6):850–78.

Beck LA, Thaçi D, Hamilton JD, Graham NM, Bieber T, Rocklin R, et al. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(2):130–9.

Snast I, Reiter O, Hodak E, Friedland R, Mimouni D, Leshem YA. Are biologics efficacious in atopic dermatitis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19(2):145–65.

Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, Beck LA, Blauvelt A, Cork MJ, et al. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus Placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(24):2335–48.

Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, Cather JC, Weisman J, Pariser D, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2287–303.

de Bruin-Weller M, Thaçi D, Smith CH, Reich K, Cork MJ, Radin A, et al. Dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroid treatment in adults with atopic dermatitis with an inadequate response or intolerance to ciclosporin A or when this treatment is medically inadvisable: a placebo-controlled, randomized phase III clinical trial (LIBERTY AD CAFÉ). Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(5):1083–101.

Dupixent (dupilumab) 300 mg solution for injection in preflled syringe and pen: summary of product characteristics. Paris: Sanof-Aventis Groupe. 2019. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/8553/smpc#gref. Accessed 31 Oct 2020.

Dupixent® (dupilumab) injection, for subcutaneous use: US prescribing information. Tarrytown: Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 2019. https://www.regeneron.com/sites/default/files/Dupixent_FPI.pdf. Accessed 31 Oct 2020.

Dupixent (dupilumab). Summary of Product Characteristics. European Medicines Agency. 2017. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/dupixent-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 31 Oct 2020.

Mason KJ, Barker JNWN, Smith CH, Hampton PJ, Lunt M, McElhone K, et al. Comparison of drug discontinuation, effectiveness, and safety between clinical trial eligible and ineligible patients in BADBIR. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(5):581–8.

Yiu ZZ, Mason KJ, Barker JN, Hampton PJ, McElhone K, Smith CH, et al. A standardization approach to compare treatment safety and effectiveness outcomes between clinical trials and real-world populations in psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(6):1265–71.

Hanifin JM, Thurston M, Omoto M, Cherill R, Tofte SJ, Graeber M, et al. The Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI): assessment of reliability in atopic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol. 2001;10(1):11–8.

Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)–a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210–6.

Armario-Hita JC, Pereyra-Rodriguez J, Silvestre JF, Ruiz-Villaverde R, Valero A, Izu-Belloso R, et al. Treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab in real clinical practice: a multicentre, retrospective case series. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(5):1072–4.

Olesen CM, Holm JG, Nørreslet LB, Serup JV, Thomsen SF, Agner T. Treatment of atopic dermatitis with dupilumab: experience from a tertiary referral centre. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(8):1562–8.

Faiz S, Giovannelli J, Podevin C, Jachiet M, Bouaziz JD, Reguiai Z, et al. Effectiveness and safety of dupilumab for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in a real-life French multicenter adult cohort. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(1):143–51.

de Wijs LEM, Bosma AL, Erler NS, Hollestein LM, Gerbens LAA, Middelkamp-Hup MA, et al. Effectiveness of dupilumab treatment in 95 patients with atopic dermatitis: daily practice data. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(2):418–26.

Akinlade B, Guttman-Yassky E, de Bruin-Weller M, Simpson EL, Blauvelt A, Cork MJ, et al. Conjunctivitis in dupilumab clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(3):459–73.

Wang C, Kraus CN, Patel KG, Ganesan AK, Grando SA. Real-world experience of dupilumab treatment for atopic dermatitis in adults: a retrospective analysis of patients’ records. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59(2):253–6.

Tauber M, Apoil PA, Richet C, Laurent J, De Bonnecaze G, Mouchon E, et al. Effect of dupilumab on atopic manifestations in patients treated for atopic dermatitis in real life practice. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180(6):1551–2.

Ruiz-Villaverde R, Dominguez-Cruz J, Armario-Hita JC, Martinez-Pilar L, Alcantara-Luna S, Pereyra-Rodriguez JJ. Fifty two week follow-up safety and effectiveness results of dupilumab treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis from a retrospective, multicentric series. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32(4):e12931.

Ou Z, Chen C, Chen A, Yang Y, Zhou W. Adverse events of dupilumab in adults with moderate-to severe atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;54:303–10.

Thyssen JP, Toft PB, Halling-Overgaard AS, Gislason GH, Skov L, Egeberg A. Incidence, prevalence, and risk of selected ocular disease in adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(2):280-286.e1.

Treister AD, Kraff-Cooper C, Lio PA. Risk factors for dupilumab-associated conjunctivitis in patients with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(10):1208–11.

de Wijs LEM, Nguyen NT, Kunkeler ACM, Nijsten T, Damman J, Hijnen DJ. Clinical and histopathological characterization of paradoxical head and neck erythema in patients with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab: a case series. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(4):745–9.

Fowler E, Silverberg JI, Fox JD, Yosipovitch G. Psoriasiform dermatitis after initiation of treatment with dupilumab for atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2019;30(3):234–6.

Tracey EH, Elston C, Feasel P, Piliang M, Michael M, Vij A. Erythrodermic presentation of psoriasis in a patient in treated with dupilumab. JAAD case rep. 2018;4(7):708–10.

Safa G, Paumier V. Psoriasis induced by dupilumab therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:e49–50.

Newcomb DC, Boswell MG, Zhou W, Huckabee MM, Goleniewska K, Sevin CM, et al. Human TH17 cells express a functional IL-13 receptor and IL-13 attenuates IL-17A production. J allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(4):1006-13.e1–4.

Willsmore ZN, Woolf RT, Hughes C, Menon B, Kirkham B, Smith CH, et al. Development of inflammatory arthritis and enthesitis in patients on dupilumab: a case series. B J Dermatol. 2019;181(5):1068–70.

Guenova E, Skabytska Y, Hoetzenecker W, Weindl G, Sauer K, Tham M, et al. IL-4 abrogates Th17 cell-mediated inflammation by selective silencing of IL-23 in antigen-presenting cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:2163–8.

Flanagan K, Sperling L, Lin J. Drug-induced alopecia after dupilumab therapy. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5(1):54–6.

Carnicle JM, Hendricks AJ, Shi VY. Reactivation of alopecia areata after dupilumab therap for atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2020;. https://doi.org/10.1097/DER.0000000000000512.

Smogorzewski J, Sierro T, Compoginis G, Kim G. Remission of alopecia universalis in a patient with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5(2):116–7.

Zhu GA, Kang KJ, Chen JK, Novoa RA, Brown RA, Chiou AS, et al. Inflammatory alopecia in patients on dupilumab: a retrospective cohort study at an academic institution. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(4):e159–61.

Doyle LA, Sperling LC, Baksh S, Lackey J, Thomas B, Vleugels RA, et al. Psoriatic alopecia/alopecia areata-like reactions secondary to anti-tumor necrosis factor-α therapy: a novel cause of noncicatricial alopecia. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33(2):161–6.

Wollenberg AN, Beck LA, Blauvelt A, Simpson EL, Chen Z, Chen Q, et al. Laboratory safety of dupilumab in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from three phase III trials (LIBERTY AD SOLO 1, LIBERTY AD SOLO 2, LIBERTY AD CHRONOS). Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(5):1120–35.

Agache I, Song Y, Posso M, Alonso-Coello P, Rocha C, Solà I, Beltran J, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a systematic review for the EAACI Biologicals Guidelines. Allergy. 2020;. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.14510.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Kaderina Stylianou, Dawn Lavery (dermatology advanced nurse practitioner) and Sarah Clarke (dermatology specialist nurse) for help with data collection.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Firas Constantin Kreeshan and Ali Al-Janabi have no conflicts of interest. Richard Bruce Warren has received research grants and consulting fees: research grants: AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Lilly, Leo, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB; consulting fees: AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Arena, Avillion, Bristol Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Janssen, Leo, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi and UCB. Hamish John Alexander Hunter has received research grants and consulting fees: research grants: Pfizer, Janssen, Merck Serono; consulting fees: La Roche-Posay, Janssen, Abbvie, UCB, Sanofi Genzyme, Novartis, Almirall, Leo and Eli Lilly.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kreeshan, F.C., Al-Janabi, A., Warren, R.B. et al. Real-World Experience and Laboratory Monitoring of Dupilumab in Patients with Moderate to Severe Atopic Dermatitis in a Tertiary Centre. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 11, 149–160 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-020-00469-6

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-020-00469-6