Abstract

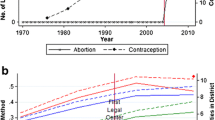

Beginning August, 2012, the U.S. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) required new private health insurance plans to cover contraceptive methods and counseling without requiring an insured’s copay. The ACA represents the first instance of federally mandated contraception insurance coverage, but 30 U.S. states had already mandated contraceptive insurance coverage through state-level legislation prior to the ACA. This study examines whether mandated insurance coverage of contraception affects contraception use, abortions, and births. I find that mandates increase the likelihood of contraception use by 2.1 percentage points, decrease the abortion rate by 3 %, and have an insignificant impact on the birth rate. The results imply a lower-bound estimate that the ACA will result in approximately 25,000 fewer abortions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Small firms are defined as those with 3–199 employees; large firms have 200 or more employees.

The five leading methods are the diaphragm, one- and three-month injectables, IUDs, and oral contraceptives.

These estimates include only HMO, PPO, and POS plans, and therefore may not be representative of plans for a significant proportion of individuals.

These methods include intrauterine devices (IUDs), injectables, and implants. Because the implant was discontinued in 2002, it was excluded from the final analysis. Copays remained in place for oral contraceptives in an attempt to incentivize switching to contraception methods with the lowest failure rates.

The estimated costs are dependent on the type of insurance coverage; therefore, the upper bound of the cost represents the uncovered cost of contraception.

Typical usage refers to actual use, which includes both inconsistent and incorrect use.

Trussell’s estimates are derived using the 1995 and 2002 National Survey of Family Growth.

I am unaware of any specific legislation that might have been responsible for such large changes in the composition of teenage contraception use relative to adults, and determining whether changes in social norms played a role is beyond the scope of this article. The change in composition is mainly driven by a decrease in condom usage coupled with an increase in oral contraceptives and injectable usage.

Between 1998 and 2009, 10 % to 16 % of individuals in the United States obtained insurance coverage through Medicaid and are therefore unaffected by mandates (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010).

Differences for plans at the local level are used for comparison because plans determined at the national level are more likely to adhere to state mandates. More than one-half (58 %) of insurance companies report determining rates at the national level.

More specifically, birth rates are available from 1993–2011, but abortion rates are available only through 2009.

For regressions involving age subgroups, the rate is calculated as the number of births per 1,000 women within that subgroup.

Specifically, starting in 1998, California and New Hampshire do not report abortion statistics, and are therefore not included in the abortion analysis. Alaska, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and West Virginia do not report in all years, but they report in a majority of the years.

Controls include the percentage of the population that has employer insurance, median household income, whether emergency contraception is available over the counter, the unemployment rate, the average number of children per household, the average number of children less than age 5 per household, percentage of the population that is married, percentage of the population that is nonwhite, percentage of the state with high school and college diplomas, the median age of women, and percentage of the population enrolled in Medicaid.

This result is similar if an indicator for blue states is included instead of the percentage of the votes in the 1996 presidential election.

Results are from linear probability models, but results from probit estimation are similar. The regressions include all controls listed in Table 2.

Additionally, following Levine et al. (1996), models were estimated using the “pregnancy rate” as the outcome variable. The pregnancy rate is a constructed measure defined as the sum of the abortion rate and the birth rate, and serves as an approximation to the number of pregnancies per 1,000 women aged 15–44. The results are very similar to results using abortion and birth rates as outcome variables, and are available upon request.

The baseline fertility outcomes are calculated as the average in 1997, which was the year prior to the first mandate introduction. The baseline abortion (birth) rate is 17.3 (63.5).

The pre-mandate effect for birth rates for the age 20–29 subsample is significant. The effect in the first year following the mandate is statistically different from the pre-mandate effect (p = 0.001).

Robustness checks by age subgroup are available upon request.

Sterilization procedures and patient education and counseling are also included under the new coverage laws; the law does not include coverage of abortifacient drugs.

In an effort to give insurers the flexibility to control costs, certain forms of cost sharing will be allowed. Specifically, if a generic brand is available for certain contraceptives, the insurance company can impose cost sharing for the branded drug.

As mentioned in the introduction, the case Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. muddles the issue of whether religious exemptions will have negligible effects, but this should be studied as more post-ACA data become available.

References

Bitler, M., & Schmidt, L. (2006). Health disparities and infertility: Impacts of state-level insurance mandates. Fertility and Sterility, 85, 858–865.

Bitler, M., & Schmidt, L. (2012). Utilization of infertility treatments: The effects of insurance mandates. Demography, 49, 125–149.

Culwell, K., & Feinglass, J. (2007). The association of health insurance with use of prescription contraceptives. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 39, 226–230.

DeNavas-Walt, C., Proctor, B. D., & Smith, J. C. (2010). Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2009 (Current Population Reports, No. P60-238). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Finer, L., & Henshaw, S. (2006). Disparities in the rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 38, 90–96.

Gruber, J. (1994). State-mandated benefits and employer-provided health insurance. Journal of Public Economics, 55, 433–464.

Hamilton, B., & McManus, B. (2012). The effects of insurance mandates on choices and outcomes in infertility treatment markets. Health Economics, 21, 994–1016.

Henne, M., & Bundorf, K. (2008). Insurance mandates and trends in infertility treatments. Fertility and Sterility, 89, 66–73.

Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, & Health Research and Educational Trust (HRET). (1999). Employer health benefits: 1999 Annual Survey. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation.

Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, & Health Research and Educational Trust (HRET). (2003). Employer health benefits: 2003 Annual Survey. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation.

Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, & Health Research and Educational Trust (HRET). (2010). Health insurance coverage in America, 2009. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation.

Jones, R., Darroch, J., & Henshaw, S. (2002). Contraceptive use among women having abortions in 2000–2001. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 34, 294–303.

Kaestner, R., & Simon, K. (2002). Labor market consequences of state health insurance regulation. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 56, 136–159.

Kearney, M., & Levine, P. (2009). Subsidized contraception, fertility, and sexual behavior. Review of Economics and Statistics, 9, 137–151.

Levine, P., Trainor, A., & Zimmerman, D. (1996). The effect of Medicaid abortion funding restrictions on abortions, pregnancies and births. Journal of Health Economics., 15, 555–578.

Liang, S., Grossman, D., & Phillips, K. (2011). Women’s out-of-pocket expenditures and dispensing patterns for oral contraceptive pills between 1996 and 2006. Contraception, 83, 528–536.

Mellor, J. (1998). The effect of family planning programs on the fertility of welfare recipients: Evidence from Medicaid claims. Journal of Human Resources, 33, 866–895.

Mosher, W., & Jones, J. (2010). Use of contraception in the United States: 1982–2008. (Vital and Health Statistics Report - Series 23, No. 29). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

National Conference of State Legislatures. (n.d.). Insurance coverage for contraception laws. Retrieved from http://www.ncsl.org/default.aspx?tabid=14384

Planned Parenthood. (n.d.). Birth control. Retrieved from http://www.plannedparenthood.org/health-topics/birth-control-4211.htm

Postlethwaite, D., Trussell, J., Zoolakis, A., Shabear, R., & Petitti, D. (2007). A comparison of contraceptive procurement pre- and post-benefit change. Contraception, 76, 360–365.

Schmidt, L. (2007). Effects of infertility treatment insurance mandates on fertility. Journal of Health Economics, 26, 431–446.

Sonfield, A., Gold, R., Frost, J., & Darroch, J. (2004). U.S. insurance coverage of contraceptives and the impact of contraceptive coverage mandates, 2002. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 36, 72–79.

Trussell, J. (2011). Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception, 83, 397–404.

Wolfers, J. (2006). Did unilateral divorce laws raise divorce rates? A reconciliation and new results. American Economic Review, 96, 1802–1820.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the Editor and two anonymous referees for comments that substantially improved this article. I am especially grateful to Jason Abrevaya, Daniel Hamermesh, Sandra Black, and Steve Trejo for their feedback and invaluable guidance. I also thank Mark Hayward, John Smith, and participants at the Labor lunch seminar at UT-Austin for their useful comments and feedback.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mulligan, K. Contraception Use, Abortions, and Births: The Effect of Insurance Mandates. Demography 52, 1195–1217 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-015-0412-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-015-0412-3