Abstract

Higher educational institutions tend to draw from mainstream approaches to environmentalism that reinforce race, class, and gender hierarchies around who constitutes “an environmentalist” and what activities constitute “environmentalism.” As a result, students of color and students from other marginalized backgrounds who often experience environmental degradation and catastrophe firsthand do not often see their experiences reflected in universities’ environmental programming, curricula, or research. Furthermore, faculty and staff who center issues of race, equity, power, and justice when addressing environmental topics tend to work in isolation from one another and their efforts are not well-coordinated. In this paper, we draw from the concept of “epistemic exclusion” (Settles et al. J Divers High Educ 14:493, 2021; J High Educ 93:31–55, 2022) to explain hidden biases that systematically devalue scholarship that does not fit mainstream parameters. We describe a research project focused on building more equity-centered environmental efforts at the University of California, Santa Cruz. We find that faculty and staff across divisions want to engage in more epistemically inclusive and equity-centered environmental work, but lack the institutional support and resources (e.g., knowledge, funding, time, incentives) to do so. Interestingly, only a few responses focused on the barriers and biases related to epistemic exclusion. Our findings suggest that more awareness is needed to identify, analyze, and challenge these less visible barriers to substantively work towards greater inclusivity in environmentalism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In institutions of higher education, environmentalism is commonly understood through a mainstream lens, one that generally presumes an idea of “non-human nature,” in which humans are separate from nature and wilderness is a site for romantic contemplation (Packer 2010), recreation (Braun 2003), and preservation (Guha 1989). In his influential essay “The Trouble with Wilderness,” environmental historian William Cronon (1996) articulates the ways such conceptualizations reinforce whiteness, class privilege, settler colonialism, and masculinity—notions deeply rooted in US nation-making and contemporary politics and policy (see also Purdy 2015). Reification of “pristine” nature dismisses the importance of working landscapes and urban spaces and the people and livelihoods associated with them (Cronon 1996). Mainstream environmentalism also sets up racial and gendered profiles of what constitutes “an environmentalist” that are held widely today. In a national study, Pearson et al. (2018) found broad consensus as to who constitutes an environmentalist: members of all racial, ethnic, and class backgrounds surveyed described an environmentalist as white, wealthy, highly educated, and young. In addition, both white and non-white respondents disassociated non-whites from environmentalists, despite the fact that people of color reported significantly higher levels of environmental concern, on average (Pearson et al. 2018: 12431).

In addition to privileging certain spaces and groups of people, mainstream environmentalism also amplifies certain forms of knowledge and knowledge holders as those best positioned to address ecological degradation. As Overland and Sovacool (2020) show, western countries center natural science viewpoints and environmental innovation focuses on quantitative knowledge and technological advancement. In fields like conservation or ecological science and adjacent fields (climate/atmospheric-, geo-, earth-sciences), “problems” and “solutions” are defined in narrow, technical terms, with problems perceived as identifiable, measurable, and therefore solvable (Latour 1999). Large-scale social processes like colonial expropriation and racial capitalism that shape both nature and society are often understood to be beyond the scope of such scientific studies and thus understudied or ignored (Lövbrand et al. 2020; Walker 2007). Similarly, mainstream environmental undergraduate curricula heavily favor the natural sciences over the social sciences and humanities (Strang 2007) and often do not examine the inequalities being exacerbated by the Western world’s response, or lack thereof, to various environmental crises (Ferreira 2017). This elevates Western forms of environmental knowledge production (e.g., quantitative, scientific approaches), while marginalizing knowledges derived from lived experiences, cultural traditions, community practices; large-scale historical and political analyses; and equity and justice-centered approaches to environmentalism.

The latter approach is what we refer to as “critical environmentalism.” In using this term, we take inspiration from Gould et al. (2018) in their assertion that broader interpretations of the environment are needed—in place of universalist, ahistorical, and homogenizing framings—towards more expansive, dynamic, multifaceted, and socially constructed notions of environment. Formally, the use of the term “critical” signals work in the tradition of “critical social theory,” a tradition originating with Marx but formalized by the Frankfurt School (Horkheimer 1982 [1937]). It marks a contrast from “traditional” or “mainstream” approaches in seeking to illuminate and expose the injustices, inequalities, and ideologies of present social formations—with an eye toward changing them (Brenner 2009). A social justice-centered approach to environmental studies centers on themes of power relations, epistemology, and social constructions of difference to study the relationships between humans, non-humans, and the environment (Pepper et al. 2003). Cole (2007) claims that teaching environmental studies through a critical lens improves students' understanding of the environment and how it interacts with humanity.

In this paper, we argue for the necessity of promoting more equitable, inclusive, and critical environmental approaches within higher education to offset the dominance of technical, scientific, and mainstream ones. We share research conducted from 2021 to 2023 with faculty and staff on our campus whose work sits at the nexus of environmental and social justice. We wanted to know about their experiences as environmental scholars on a campus that has historically maintained a mainstream environmental focus while simultaneously enrolling a diverse undergraduate student body. We asked faculty and staff questions about the kinds of obstacles they encounter and how the institution could best support their work. These perspectives, which often intersect with identities and experiences that have been historically marginalized in environmentalism and academia, challenge narrow definitions of environmentalism and work to create broader, more expansive notions of who is doing environmental work. Such approaches also speak to and enable the next generation of environmental activists to support communities at the front lines of environmental and climatic changes.

To better understand the challenges of fostering a more inclusive environmentalism, we draw from the concept of epistemic exclusion, a concept currently emerging within the literature on higher education. Epistemic exclusion refers to the devaluation of scholarship by individuals and institutions that is outside of the mainstream, especially by scholars who hold marginalized identities (Settles et al. 2019: 796). It draws attention to the multiple ways academic gatekeeping reflects disciplinary and identity biases which in turn perpetuate a methodological and intellectual status quo around what kind of scholarship is deemed meritorious, and which scholars are credible and qualified (Settles et al. 2020, 2022). Academic gatekeeping determines “who has access” to academia, “socializing trainees into disciplinary norms and removing those who fail to meet these standards” (Settles et al 2022: 32). It also determines the boundaries of a discipline, and values and devalues certain kinds of scholarship and scholars. Devaluation can happen formally (e.g., article rejections, tenure denials) or informally (e.g., misrepresenting one’s work or minimizing accomplishments). Churcher (2022) argues that universities are shaped by and reproduce shared imaginings and attachments that maintain masculinist, Eurocentric, and Western forms of epistemic privilege. Knowledge is associated “with generality and abstraction…in the pursuit of ‘fundamental truths,’” rather than “particularity, embodiment, situatedness, power, and context,” which are considered peripheral and subordinate (Churcher 2022: 899). Within this context, disciplinary norms and gatekeeping around them are thought to be neutral, objective activities in service to the discipline, rather than subjective, historical, and fraught with personal bias and structural oppression.

The consequences of unaddressed epistemic exclusion include a hostile work environment for those from marginalized identities; barriers to publication, tenure, and promotion; and maintenance of established disciplinary boundaries. It disproportionately affects “women and faculty of color due to negative stereotypes about their competence, and their likelihood of engaging research out of the disciplinary mainstream” (Settles et al. 2022: 32) and places them in a Catch-22: they are both hypervisible, as scholars from underrepresented backgrounds, yet their scholarly successes are rendered invisible or unworthy, making scholarly achievement harder to attain. Yet epistemic exclusion is difficult to test for since metrics of merit, like securing grant funding, high-scoring teaching evaluations, and publishing in high-ranking journals are supposedly “identity-neutral.” This maintains the sense of entitlement of dominant social actors. Marginalized social actors are not immune from the pull of dominant epistemic communities, so these processes can have a co-opting effect, further undermining networks of solidarity, trust, and concern.

Despite a paucity of research to date, epistemic exclusion applies well to the field of environmentalism. Almost 30 years ago, Lewis and James (1995) called into question the idea of environmental education as universal (e.g., that environmental education programs appeal to all audiences) and inclusive (e.g., that the needs of people of color are recognized and addressed). That the environmental field remains, decades later, predominantly white and privileged speaks to the persistence of normative (yet often unrecognized) racial, class, and epistemological structures that overtly and covertly exclude the environmentalisms and knowledges of marginalized groups. Mainstream approaches arguably do not resonate with underrepresented groups, who are then not motivated to participate; yet this refusal is often interpreted as a lack of concern, knowledge, or awareness. Consequently, diversity, equity, and inclusion problems persist in environmentalism partly as a result of the uninterrogated assumptions, racist stereotypes, and reproduction of structures by those in power. Epistemic exclusion is, thus, a form of institutional racism, whereby dominant scholars maintain the disciplinary status quo and their position on top of the hierarchy (Bhopal 2017).

Environmental sociologist Dorceta Taylor (2018) has characterized most diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts of universities as “halfhearted,” “tentative,” and “superficial.” She highlights the necessity of “effective mentoring and engaged learning opportunities to nourish their [diverse students’] interests…[and learning opportunities] that incorporate the life experiences, expertise, and ideas of people of color” ( 2018: 384, emphasis added). Taylor’s research has found that there is a “robust pool of minority students who are pursuing degrees in a wide array of environmental programs” who consider diversity and equity very or extremely important in choosing where to work (2007: 39), and thus, argues that environmental programs must make “fundamental changes in [their] ideology, structure, and operations of programs” and that universities require “systematic and extensive institutional change” (Taylor 2007: 40).

The institutional changes that Dorceta Taylor calls on environmental programs to make require recruiting and retaining faculty of diverse backgrounds and identities. In a recent study of the University of California (UC) and California State University (CSU) systems, Taylor et al. (2022) found that while “students of color represent 58.2% (UC) and 52.4% (CSU) of the student population within environmental studies departments, faculty of color only represent 22.5% (UC) and 17.7% (CSU) within these departments” (490). This disparity is especially problematic in institutions that enroll large numbers of historically underrepresented students, given that these institutions could act as rich sources to increase diversity in the career pipeline if properly nurtured.

To the extent that mainstream environmental studies departments fail to consider issues of epistemic exclusion in their approach to diversity, equity, and inclusion, they fail to create the changes necessary to support faculty or students from underrepresented groups. In this paper, we argue that addressing the persistence and invisibility of epistemic exclusion, and collectively working towards epistemic inclusion—i.e., broadening disciplinary boundaries and redefining the topics, methodologies, and scholars that are deemed legitimate—can transform environmentalism in higher education. It can make meaningful systematic institutional changes and improve the recruitment and retention rates of faculty of color and the students they support.

In the sections that follow, we discuss a research project we conducted, dubbed “Critical Environmentalisms,” in which we examined the experiences of 58 critically oriented environmental faculty and staff on the University of California, Santa Cruz campus. Through a series of surveys and interviews, we examined both the institutional barriers and ideal forms of support that would enable participants to do more inclusive environmental work—for the campus to live up to the values of epistemic inclusion it promotes. We found that (1) barriers to doing more inclusive environmental work included a lack of time and access to a network of similarly minded scholars and resources, lack of knowledge in how to work with and support BIPOC students, and too few incentives to pursue this work; and (2) that opportunities for authentic and non-hierarchical networking, collaboration and relationship-building across sectors (e.g., departments, job classifications, campus resources) are central to supporting critical environmental work. Based on these findings, we argue that epistemic inclusion is not simply about more funding or more time for critical environmental work (though that helps); it is also about creating support networks and shared resources that will allow this work to flourish, be more visible, and have a sustained influence on campus.

UCSC as a case study

The University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) is a unique site to examine the tensions between mainstream and critical environmentalism, and the kinds of epistemic exclusions that limit advancement of more marginalized environmental perspectives. On one hand, the campus is a nationally recognized leader in environmentalism. The university is located on a 200-acre hill, nestled in redwood forest, with sweeping views of the Monterey Bay. Since its founding, UCSC has attracted faculty, staff, and students who were drawn to the natural beauty of the campus and town (Reti et al. 2020). Located in the Central Coast, a major agricultural center nationally, the campus has become a site for the development of agroecology, training generations of farmers through an apprenticeship program located on the campus’ long-running farm and garden (Reti et al. 2020). Its Environmental Studies department is one of the oldest in the nation and has a strong reputation. As a large, public, university that enrolls roughly 20,000 students and employs nearly 3500 faculty and staff (University of California 2020), environmental organizations, programming, courses, and internships abound.

On the other hand, major disparities in institutional resources and support exist between STEM and “hard” science approaches to environmentalism versus more critical, humanist, interpretive, or theoretically-based approaches on campus. For example, the campus recently established a department focused specifically on the Environmental Sciences, separate from the Environmental Studies department, although the latter already focuses on bridging social and ecological sciences in an interdisciplinary manner. The Environmental Studies department has the highest percentage of white staff and students (undergraduate and graduate) in the Division of Social Sciences, and tends to be dominated by white faculty members (for example, the prior chair (2020–2023) was the first person of color in that role, and there has never been a woman of color chair in the department’s 50 + year history). Students, staff, and faculty who identify as white and their associated interests (e.g., conservation, wildlife, plants) tend to be overrepresented in institutional curricula and programming; the Environmental Studies department did not even start a concentration in environmental justice until a few years ago. Scholars who do social science and humanistic environmental work are scattered across campus departments and maybe the lone scholar in their department doing that kind of work.

As a result, students from marginalized backgrounds often have difficulty identifying with and engaging in environmental work. UCSC is a Hispanic-serving institution (HSI) and an Asian-American and Native American Pacific Islander-serving institution (AANAPISI), and students of color make up a majority of the student population. But they often feel deterred from environmental studies due, in part, to the lack of representation and sense of belonging (Dare 2021; Koscher 2017; Pack 2014; Taylor 2018). For example, around 2014, UCSC’s Ethnic Resource Centers—dedicated to the retention and success of Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) students—started hearing more frequently that environmental spaces on campus were unwelcoming, that students felt micro-aggressed in environmental courses, and that important concerns they faced, such as food and housing insecurity, were not seen as “environmental” issues. These experiences were even undermining the retention of some students of color. The Ethnic Resource Centers started a hashtag campaign, #PoCSustainability, to begin shifting the discourse about environmental concern as being only a “white thing.” The director of the campus’s centrally-funded Sustainability Office—which had tended to focus on water conservation, zero waste, energy efficiency, and other mainstream environmental concerns—wanted to remedy the pervasive whiteness of their unit, and took the initiative to reach out to and show up in BIPOC-centered spaces. One of the authors, Flora Lu, then Provost of College Nine and John R. Lewis College, worked with the Ethnic Resource Centers and Sustainability Office to form a new initiative, the People of Color Sustainability Collective (PoCSC) to define and pursue the goal of inclusive sustainability (Lu et al. 2018). PoCSC has won multiple awards and informed similar efforts at other UC and CSU campuses (Lu and Murai 2023).

Thus, UCSC is a relevant case of the kinds of dynamics that play out between mainstream and critical environmentalisms. Examining the specific institutional barriers to critical approaches can provide insights into how epistemic exclusions operate within environmentalism more generally. Relatedly, it is no coincidence that all four authors on this paper (three faculty and one recent undergraduate) are from underrepresented groups. The project derives from our own experiences with environmental epistemic exclusions. A chance encounter between Emily Murai, Hillary Angelo, and Flora Lu led to a conversation about our shared interests in critical approaches to environmentalism and the difficulties of finding faculty of similar interests. In the absence of available information, we wanted to learn how many critically oriented environmental scholars there were on campus, what they were working on, what their experiences as critical scholars were, and what could be done to build a stronger campus network of social justice-oriented environmental scholars, staff and students. We applied for a small grant through the campus’s “Building Belonging” program—which supports underrepresented undergraduates through faculty-mentored research—for a survey and interview project we called Identifying Critical Environmental Work and Needs on Campus. The responses gave us insight into the ways epistemic exclusions marginalize and isolate knowledges and practices that threaten the status quo of the neo-liberal university and maintain dominant environmental frameworks, imaginaries, and methods.

Methods

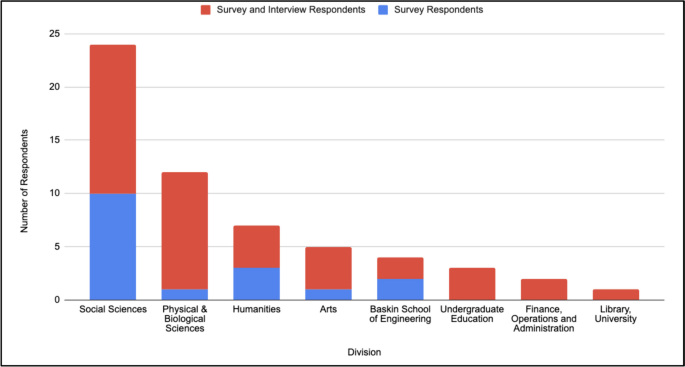

We used a scaffolded process to gather data in the 2021–22 academic year. First, we used campus websites, word-of-mouth, and existing networks to compile a comprehensive list of faculty, staff, and organizations doing critical environmental work on campus, which included 55 people and 42 programs/initiatives. Then we designed a survey to learn more about this work. The instrument used a combination of open-ended and multiple-choice questions to inquire about the respondent’s academic training, methodological and pedagogical approaches, and curricular, co-curricular, or extra-curricular efforts. Additionally, the survey asked what, if any, barriers the respondent faced in pursuing critical environmental work at the university, and what kinds of institutional resources and support might enhance their work. After pre-testing and revising the survey, we invited 58 people to take it—a few more than the group we additionally identified through word of mouth—and received 39 responses (67% response rate). Demographically, two-thirds of the respondents were women and two-thirds were white, non-Hispanic. Figure 1 provides a divisional breakdown of respondents.

To further investigate the kinds of institutional changes that would support critical environmental work on campus, we invited survey participants for a follow-up interview. Follow-up interviews gave respondents a chance to elaborate on their responses and give deeper insight into their thought processes (Clarke and Braun 2013; Staveteig et al. 2017). Thirty of the 39 survey participants agreed to participate in an interview, but due to scheduling constraints, we ended up interviewing only 18 original survey respondents (31%). For these interviews, we asked respondents to respond to set of four targeted questions: (a) what kinds of policy and/or actions could be taken to improve critical environmentalism on campus; (b) how to improve communication on campus; (c) what institutional support models they would like to see implemented; and (d) how they foresee interacting with a critical environmentalism network. These questions were derived from the initial survey results and were designed to pinpoint specific barriers and kinds of support faculty and staff need to do critical environmental work effectively.

We conducted another set of interviews with respondents who did not complete the initial survey. This additional set of data supplemented responses from both the survey and interview and was an effort to ensure better representation across campus (i.e., divisions and units that were not well-represented by data collection up to that point). We asked prior respondents for names and specifically followed up with those people. We only conducted verbal interviews with this group: the survey was administered verbally and the same follow-up questions were asked. Of the 33 faculty who were identified and contacted, 19 interviews (57%) were conducted. In total, 37 interviews were conducted.

Because this research is institutional and was conducted for institutional purposes, we were not required to gain Human Subjects clearance by the Institutional Review Board.

Results

Critical environmental efforts

Our research identified 43 campus initiatives, organizations, and centers that report promoting critical environmentalism,Footnote 1 from field sites and laboratories to political mobilization groups (e.g., UC Green New Deal Coalition). Some are focused on recruiting diverse populations into predominantly white spaces (e.g., STEM fields), while others center on technological innovations to address environmental problems (e.g., the Agri-Food Technology Research Project). Other efforts are student-led. The Education for Sustainable Living Program is a student organization that offers courses about transitioning society to prioritize the environment and humanity.

The more exciting initiatives from an epistemic inclusion perspective traverse disciplinary and campus/community boundaries to interrogate notions of identity, expertise, and equity. The Science and Justice Center, for example, innovates experimental spaces, engages in collaborative research practices, and fosters emerging alliances that traverse multiple intellectual, institutional and ethico-political worlds to confront species extinction, toxic ecologies, and other contemporary matters of concern that undermine livable worlds. The Apprenticeship in Community Engaged Research or (H)ACER program promotes reflexive, real-world, praxis-oriented efforts in which students collaborate with off-campus partners to address pressing issues such as economic, educational, and environmental injustice through an approach that honors the cultural, social, and epistemological strength of community members. The Critical Realities Studio is a hybrid studio/lab for critical theory and art practice to engage, using algorithmic and intersectional methods, with pressing issues including climate change, gendered violence, racism, and colonialism. These efforts are designed and led by groups of queer women and women of color, and they pay close attention to particularity, situatedness, power, context, and embodiment, rather than universality, generality, and abstraction (Churcher 2022).

While these examples highlight an exciting array of opportunities around critical environmentalism, these efforts are not well coordinated and often lack financial support and security (e.g., they are sponsored by external grants rather than permanent funding through the institution), which undermines their continuity. Programs and resources have to reinvent themselves over and over again at the expense of programming depth, duplication, and permanence.

Challenges to critical environmental work

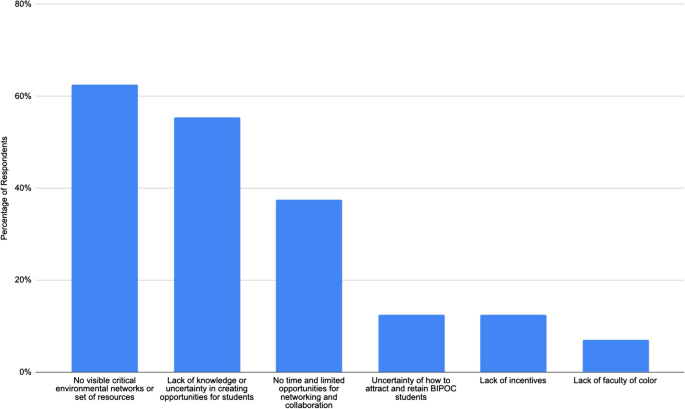

Although many faculty and staff on campus are working on supporting a more equitable environmental education and want UCSC to be a leader in this area, respondents described barriers that prevent the university from realizing this goal (Fig. 2). The results highlight three general categories of obstacles: a lack of networks and collaboration; a need to better engage and support students in critical environmental opportunities; and the invisibilization of and institutional deterrents to such work.

Given the need for interdisciplinarity, one barrier towards more critical environmental work is the difficulties of forging inter-departmental collaborations, a challenge noted by 21 respondents (37.5%). Departments and divisions are perceived as distinct, “siloed” entities, and as a result, most faculty and staff report that they do not have the time or opportunity for interdisciplinary networking, collaboration, and co-teaching. Respondents said it was easy for them to find connections within their departments and divisions, but hard to meet people outside of them. This “silo-ing” is not only a result of the hard sciences being favored over other areas, but also of the physical layout of the campus. In the early 1960s, UCSC’s founders deliberately designed the campus to be highly decentralized to avoid the protests and student organizing that were happening on other campuses at the time (Reti et al. 2020). This now affects faculty and staff who are engaged in critical environmental efforts by making it challenging to meet people outside of their departments and find those who are doing similar work. As one respondent explained, “The fact that these academic territories are carved up means that often there is not a lot of communication that is centralized… and that means in certain ways there’s a limitation on the scope of collaborative possibilities and communication.” This also prevents collaboration across divisions because there is no physical interdisciplinary space for faculty and staff interested in critical environmentalisms to meet on campus (a challenge noted by over 60% of respondents). As a result, respondents who indicated they were deeply involved in critical environmental work on campus still find it difficult to make interdisciplinary connections and find out what others on campus were working on, and thus tend to work in isolation. Faculty and staff have found duplicate efforts in different departments (e.g., in developing courses on these issues) that could have been done collaboratively. There is no network for people with these interests at UCSC and they did not have the time to go through every department’s website and find those with the same interests.

Faculty and staff report not knowing about many of the critical environmental internships, projects, and groups on campus that welcome student involvement and, therefore, are not able to recommend them to students. Over half of the faculty and staff who participated in this study (31 respondents or 55.4%) expressed the desire to know about and have more opportunities to help their students participate in critical environmental work on campus. Because of the separation between academic departments and divisions, students do not get cross-departmental emails or see postings for opportunities and resources outside of their home units, which impedes their ability to branch out. Seven respondents (12.5%) expressed the desire to get more BIPOC students engaged and retained in critical environmentalism. One respondent explained, “The students of color that are engaged in conversations around critical environmentalisms and sustainability are very smart, very engaged, and they have some really good ideas about what could be done to engage their experiences more,” but that resources and opportunities often did not “zero in on these students” to create the kinds of support they crave. This respondent noted that critical environmental programs and projects do not get the attention and funding that they need, and do not effectively reach the marginalized populations that are and will continue to be the most affected by environmental issues on campus and elsewhere.

Beyond an information gap about opportunities available, respondents pointed to a more fundamental shortcoming: the level of faculty awareness about critical approaches and their importance. Some respondents felt this especially applied to white faculty in STEM disciplines who often do not include critical perspectives or social justice topics in their research and courses. One respondent explained, “I feel in general that if you were talking to some of my other STEM colleagues with that narrative [of critical environmentalism]…a lot of my colleagues would not be able to understand what you are saying.” Another commented that “a significant fraction of the students of color are actually mentored by white mentors. How you get the mentors to be more self-aware about some of their own biases…so they can support the students better.” Changing the demographics of these units is key. Respondents expressed that the lack of faculty and staff of color is an obstacle to critical environmentalism on campus and an impediment to creating a diverse pipeline of faculty and staff of color in environmental fields. One respondent said that the university needs to be pushed by people “advocating really strongly for faculty hires that address how white-dominated these departments are.”

Respondents also indicated that critical environmental work was challenging because crucial aspects of such work (e.g., program building, educating colleagues, and mentoring students) are not sufficiently incentivized or rewarded. One respondent touched on this by advocating for “promotion where DEI [diversity, equity and inclusion] work is really amplified and an essential component of who we are as academics.” A junior faculty member and woman of color observed that, while she could include information about her DEI efforts in her personal statement for review, this would be to the detriment of the space she devoted to her research and publishing, given page limits. In a report about the experiences of faculty of color at UCSC, Covarrubias and Quinteros (2023) found that DEI efforts by faculty of color sustain the university but are narrowly conceived of as a lower tier of service, as compared to say, serving on a faculty senate committee. This invalidation of DEI work often results in faculty of color carrying “disproportionate workloads because they took on additional service roles that fit more traditional definitions” and potentially having a harder time getting tenure (Covarrubias and Quinteros 2023: 4). Faculty of color play an important role in ensuring the retention and academic success of students of color in predominantly white institutions and disciplines, but this labor is often invisibilized and constitutes a form of cultural taxation that impedes progress towards tenure and promotion (Taylor et al. 2022).

Faculty and staff at UCSC also feel overworked; 11 respondents (19.6%) indicated that they lack time to pursue critical environmentalism to the extent they would like. One respondent wanted “ways of overcoming institutional barriers to free people up in meaningful ways, not just invite people to get together or discussions on top of everything else because everyone is just so busy with teaching, with research, with administrative obligations at the departmental, divisional, and senate level.” Ultimately, the issue becomes one of time, rather than lack of interest, and freeing up faculty’s schedules with reductions in other areas, like administration, would be one way to support critical environmentalism on campus.

How critical environmental efforts can be supported

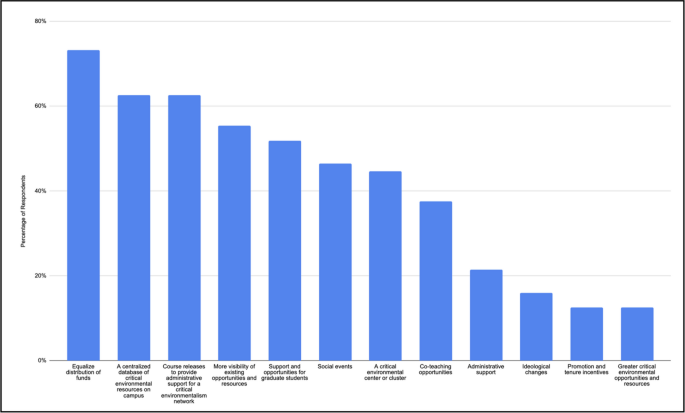

Respondents who identified these common problems they faced within the university had ideas for how to better support and amplify critical environmentalism on campus (Fig. 3). We discuss the suggestions in descending order.

Almost three-quarters of respondents (41 or 73.2%) wanted to see an equalization of funding opportunities that encouraged interdisciplinary, critical environmental work. This would give faculty and staff motivation to branch out of their departmental silos and build connections on campus.

To make more interdisciplinary connections, faculty and staff wanted a couple of different structures to be created. First, 36 respondents (64.3%) indicated they would like to see a critical environmentalism network that hosted periodic events. The idea of having a database to help scholars network with others interested in critical environmentalism was something respondents also mentioned (35 respondents, or 62.5% mentioned below). Many suggested having a webpage that kept the whole campus up-to-date on initiatives and events surrounding critical environmentalisms. One respondent said, “A web presence, some central list of people who are working and what they are working on specifically but whose work kinda fits under this broad umbrella, I think would be the first and most obvious thing that would be super helpful. Respondents also wanted a list of faculty and staff who are engaged in this work, with information about their focus (35 respondents or 62.5%), in order to reach out to people who had similar interests across departments.

Faculty (32 respondents or 57.1%) also expressed that they wanted more opportunities to get course releases to free up their time for team teaching and campus engagement. Course releases would allow them to take on more critical environmental work and have the opportunity to expand their connections to do research they would not have the capacity for otherwise.

They also wanted more graduate student researchers and staff positions to be made that address critical environmental issues and allow current faculty and staff to be less overworked (29 respondents or 51.8%). Having a professional in charge of organizing and maintaining the network would enable those engaged in critical environmental research to work across divisions and produce more fruitful work.

Next, 26 respondents (46.4%) expressed a desire to socialize in person coming out of COVID-19 and use a meet and greet as an opportunity to expand their networks across divisions and potentially collaborate with others as a result, with one respondent noting, “COVID has really limited the visibility of all of us with each other, so the first thing I think of are social things.” This was also mentioned as an opportunity for faculty and staff to present their work informally.

In addition, 25 respondents (44.6%) indicated that they would like to see a formal critical environmental center, institute, or cluster on campus that would bring with it more opportunities for research, funding, education, and student involvement. Therefore, social gatherings and physical space on campus to create these networks are essential for driving critical environmental work.

Many faculty members also wanted more opportunities for co-teaching (21 or 37.5%) to support well-rounded classes that bring in multiple different perspectives and considerations when discussing the environment. This is something that one respondent noted saying, “I would absolutely jump at the opportunity to work with people well outside of my field of expertise on shared problems… at the end of the day to do that requires time.” Therefore, co-teaching would allow faculty to both network with professors in related fields and expand their areas of expertise, but such coordination takes additional work and is not viable if it is done on top of already heavy teaching demands.

A dozen respondents (21.4%) indicated that they would like more administrative support to build and sustain critical environmentalism on campus. They would like to see someone take charge of the network as a full-time position so that others are not burdened with doing this on top of their job. This would also allow the network to take on more than it would otherwise be able to.

Respondents (9 or 16%) also wanted to see the university change its practices to be a leader in not only environmentalism but also critical environmentalism. One respondent noted, “Conceptualizing and making sense of critical environmentalism on a campus such as UCSC requires that type of intentional restructuring and institutional framing in order to begin to upset the incredibly rooted white supremacist history of food and environmentalism on this campus.” They also called for changes in the projects the university is taking on, such as the proposed new construction projects which will fundamentally change the campus and have major impacts on the environment. One respondent highlighted, “I think that the university needs to listen to its constituents, it needs to listen to its students and faculty and decisions around planning need to not be made by a couple of executive vice chancellors in closed rooms with contractors. The institutional support really needs to be around transforming the whole university and centering students, staff, and the broader community, the Indigenous community on which UCSC stands, I think the institutional support that I envision requires a full transformation of the university.” Therefore, although there are many relatively easy solutions outlined throughout this section, and broad support from faculty for such changes on campus, significant changes will also be needed to support long-term critical environmental work on campus.

Faculty and staff indicated that they would also have more time to do critical environmental work if it was incentivized. Faculty indicated that they would like tenure incentives for doing non-research work related to critical environmentalism, such as committee and grassroots work (7 respondents or 12.5%). One respondent said, “There’s not really a lot of incentive for faculty to be involved in either academic senate work that is related to fighting the climate crisis or even grassroots efforts on campus, they’re not rewarded by course releases or anything like that.” These are important elements to promoting critical environmentalisms on campus but are not things that faculty and staff have a lot of time to commit to because they are not heavily favored by the university.

Respondents (7 or 12.5%) also wanted more opportunities and resources for undergraduate and graduate students, staff, and faculty to work together on issues related to critical environmentalism. Such efforts could be incentivized for students through the establishment of a critical environmental general education requirement.

Discussion

Our research found that while there are a plethora of campus environmental initiatives at UCSC, including some innovative critical environmental projects that cross disciplinary, campus, and community boundaries, these efforts are not well-coordinated or centrally funded. This both reflects and reinforces the siloed, isolating nature of our campus community, which exacerbates the marginalization of already underrepresented groups. In addition, we found that barriers to inclusive environmental work included invisibilization and institutional deterrents such as a lack of knowledge of networks, resources, and collaboration and not knowing the best practices around engaging and supporting students in critical environmental opportunities. Respondents offered a comprehensive list of possible solutions to these issues, ranging from increasing and equalizing funding, to creating more centralized resources and networking opportunities, to ideological changes at the university.

Despite the critical environmental work that is already being done on campus, our research found that faculty and staff want to do even more. As one respondent noted about the critical environmentalism network, “I would be hoping to learn a lot about what other people are doing…I would most be thinking about learning how to do more in my own research and teaching, given that's not really a strong theme in my field.” The university needs to offer more institutional support to bridge this gap and combat the issues that are preventing this work from being done. Doing so requires a multipronged approach, from curricular changes to centralizing resources and information to hiring and retaining diverse staff and faculty (Dicochea 2012; Ferreira 2017).

What is most interesting about our pool of responses, however, is what is not said: despite being some of the most critically trained environmental thinkers on our campus, many of the solutions offered remain comfortably within institutional constraints and do not address the hidden and subtle practices of epistemic exclusion. For us, this indicates the ways in which highly operationalized, bureaucratic mindsets dominate our own ways of thinking, and the necessity to create new imaginaries that enable us to critique normalized exclusionary practices. If these practices were done away with and more inclusive, democratic practices and principles were fostered, it could potentially re-organize institutional structures such that they center greater equality and inclusion to begin with.

Programs that attempt to “diversify” their disciplines and departments through “accommodationist” practices that attempt to recruit and retain diverse students in STEM or mainstream conservation movements (Cronin et al. 2021) do not fundamentally challenge the hierarchical, exclusionary nature of these disciplines. Nor do related efforts, such as implicit bias training or diversity statements, in the absence of recognizing how fundamental white supremacy, settler colonialism, and androcentrism are to mainstream environmentalism and STEM fields. Instead, in promoting techno-solutions to environmental problems, they often replicate apolitical/decontextualized thinking that serves to perpetuate unjust power relations.

Scholarship by marginalized groups clarifies that as knowers, we are situated, and social position both confines and directs our vision and habits of attention (Dotson 2014). Overcoming the limits of one’s instituted, social imaginaries that can lead to poor epistemic habits, such as epistemic laziness, closed-mindedness, and arrogance (Dotson 2014). It will require that we become more cognizant of concepts such as positionality, reflexivity, and subjectivity, and name and challenge the hidden biases and oft-invisible processes of epistemic exclusion and their consequences.

The most innovative critical environmental programs and initiatives, as we see in several examples at UCSC, bring together people from different backgrounds and epistemologies to tackle contemporary problems in efforts to promote greater epistemic inclusion and diversity in scholarship. These methods and research foci are reflexive, affective, contextual, boundary crossing, and creative, and are led by queer women and women of color, who are often the ones most epistemically excluded at the university, both invisibilized and hypervisibilized, culturally taxed, and committed to doing work that promotes a more just society. Women and/or scholars of color tend to undertake interdisciplinary work, using methods such as Indigenous methodologies, critical race theory, community-engaged scholarship that center collaboration, involvement with community (Gold 2021). As Roshanravan (2014) points out, “Because Women of Color politics seeks to affirm and build coalition among racially devalued ways of thinking, traditional knowledge-production within academic disciplines cannot contain the methodological and theoretical work of Women of Color” (42).

Productivity culture and overwork leave minoritized people with less wealth and thus less time; they are ones who pick up slack when those with more power offload labor (Covarrubias and Quinteros 2023). Respondents say that they want to do more critical environmental work, but they want to have that work recognized and compensated. Hence we see requests for course buyouts, Graduate Student Researchers, incentives to co-teach, funding support for centralized networks or an institute, and space. But these kinds of requests work within the constraints of the university. They promote a different distribution of work, but will not likely support meaningful change. Instead, when identifying problems, respondents highlighted relationality and connection as something that was lacking. This recognizes how “knowing is also interdependent, requiring the use of collective and shared epistemic resources” (Dotson 2014). We see centering more organic, authentic forms of engagement that respects and fosters the sociality of intellectual work as a purposeful means to offset the harsh disciplinary nature of the neo-liberal university, even though these practices may be less visible or quantifiable as institutional labor.

Some respondents asked for “ideological changes” at the university. They want to see the university really caring about, listening to, and serving the people at the institution. This emphasizes the very interpersonal, humanizing (and unique) potential of universities: as spaces for intellectual exchange, participation in public life, humanization through education and learning, creative and exploratory knowledge creation, systems of governance. Today, the neo-liberal university has become anything but. Scholars face pressure to conduct research that wins large grants and earns them tenure, which marginalizes public and community-based research that may actually serve the communities they study and build more trust in higher educational institutions (Fischer 2023).

Conclusion

In this paper, we have described the work we undertook as part of a research project on critical environmentalisms, the goal of which was to make critical environmental work more visible and accessible to UCSC students, faculty, and staff. The work also identified institutional challenges to critical environmental efforts in higher education. We have since implemented some specific solutions, such as establishing an online network housed on the UCSC Sustainability Office website that we hope will improve access and lead to more collaborative, interdisciplinary work. But the research underscored that, in order to redress the epistemic exclusions, academic gatekeeping, and the unequal burdens faced by marginalized scholars, UCSC must also tackle disparities in access to power and resources between disciplines and scholars. As Bhopal (2017) argues, “universities must address the racism that takes place in their institutions … and move away from a deficit focus which blames individuals” (2298). A more structural, institutional response of this kind would require the university to examine its role in perpetuating colonialist modes of research, education, and innovation, but might also make it a leader in meaningful efforts to overcome environmental exclusion.

This project underscored, too, that supporting and retaining students and faculty of color and those from other minoritized backgrounds requires a fundamental rethinking of how environmental education is done, including conceptions of the environment itself. Fully two-thirds of UCSC’s undergraduate population is non-white, and research by PoCSC has found that a significant proportion of these students confront environmental health threats and environmental racism in their home communities (Lu and Murai 2023). As mentioned, mainstream environmentalism has alienated many of these students, who are already grappling with an institution of higher education steeped in settler colonialism and white supremacy. Supporting them involves not simply superficial efforts of inclusion but environmental teaching and research that takes the structural environmental injustices students experience as within its purview.

Making these changes requires not only research into what kinds of interventions are needed, but engaging with stronger mechanisms for institutional change. This labor, we recognize, involves a certain amount of political and institutional risk (e.g., identifying shortcomings and advocating for change) and disproportionately burdens women and faculty of color who are more likely to take up the mantle of this work. How do we support junior or non-tenure-track faculty who wish to engage in this work? How do we ensure that this work is evenly supported? One way we address both questions is by creating strong networks of critical environmental advocacy both within and outside of our institutions; supporting critical environmental scholars at every stage of their career (including through teaching and mentoring undergraduates to bring them into the field); and working to advance them into positions of institutional leadership so that critical environmental scholars will be in positions to make the institutional changes we outline here. When we have multiple, overlapping networks outside of our institutions of primary affiliation (e.g., departments and universities where we work), we are less reliant upon them for emotional support and validation, which in turn may make it easier to instigate change within them.

That said, many of the things that faculty describe wanting are fairly inexpensive and would not be hard to implement at colleges of different sizes, in terms of creating opportunities to do this kind of work and establishing incentive and/or reward structures. They include opportunities for team teaching, paid opportunities for students to work with faculty on these issues, small grants or other funding for faculty to work together to develop courses or small research projects, etc. Making broad epistemically inclusive changes, like changes to hiring and curriculum, may require more political capital, but still follow institutions' stated commitments to diversity, so advocating for these changes should be politically less risky. One thing that some departments at UCSC have done that is easily replicable and low-cost, is asking candidates to include a section on contributions to diversity in promotion/tenure files. Though imperfect, it is an effort to make visible and reward this kind of labor that mostly women faculty of color take on and to remind others to do it too. These kinds of small changes that increase the visibility and raise the profile of invisible labor are ways departments can make changes while holding space for larger institutional and disciplinary buy-in.

For further insights into how students in the earliest stages of the career pipeline can be best supported within their courses and at the departmental level, we would like to center the voice of our co-author Serena Campbell, an African American, mixed-race woman who was the undergraduate researcher for this project.

As a student coming into the University of California, Santa Cruz, I had not been introduced to any information on critical approaches to environmentalism in my previous education. When introduced to the concept of environmental racism, I realized how my previous environmental education prevented me from fully engaging with what I was being taught. I decided to become a double major in Sociology and Environmental Studies in my second year of college, hoping that it would allow me to learn even more about critical approaches to environmentalism and identify potential careers. Unfortunately, when I took my first class for Environmental Studies, the focus was heavy on math and science. The course discussed fundamental chemistry and physics and examined the earth’s spheres alongside the global cycles of carbon, nitrogen and other elements. While this was important to learn to understand how earth’s systems work, the course fell short of giving me the education I was craving because it lacked an interdisciplinary curriculum. It did not have relevance to the modern world and was ahistorical as well as apolitical. I wanted to learn about contributions to environmentalism from marginalized communities and approaches to tackling climate change rooted in ending capitalism and western imperialism, but this was rarely discussed in the wider Environmental Studies department. This impacted my ability to relate to what I was learning, a phenomenon documented by Pearson et al. (2018) who found that when interdisciplinary approaches are not valued within environmental education, students from marginalized backgrounds have trouble engaging and continuing to pursue the field of study because they over-emphasize natural (“hard”) science and technical knowledge. As a result of not feeling a sense of belonging, I decided to drop the class and pursue a double major in Sociology and Critical Race and Ethnic Studies instead.

However, I still had an interest in pursuing critical approaches to environmentalism. After hearing about the Identifying Critical Environmental Work and Needs on Campus, during my third year of college, I knew I had to get involved. This experience has allowed me to address the environmental and racial issues that I have grappled with from a young age and I have been able to take agency in examining why environmental education and fields can be so polarizing to people of color. Unlike before, when I did not consider myself to be an environmentalist because I did not feel represented by the term, I now have been able to see diversity and representation within environmentalism and feel confident in considering myself to be an environmentalist among many other scholars of color who are advocating for crucial changes to be made to the field. As I conducted research for this project, I became more confident with seeing myself as a researcher and was able to broaden my understanding of who is considered a knowledge producer. I was able to reimagine what the environmental field could look like, in a way that is better prepared to tackle the environmental concerns of my generation and combat the notions of natural science superiority that are currently rampant in the field. Through this research project, I have been able to explore alternatives to mainstream environmental movements and education, and this has reshaped how I conceive of the possibilities that I am able to pursue on campus and beyond.

In order to make Environmental Studies an appealing major to students/staff/faculty who are interested in critical approaches to environmentalism, there needs to be more crossover between Environmental Studies and other departments that have critical foci. This could include social sciences, humanities, or the arts to give people a variety of critical approaches that they can use to then center environmentalism. Environmental Studies departments and majors also create meaningful change by being open to interdisciplinary collaboration whether it is in teaching, research, or in service work. This collaboration can be done with departments with critical focuses that attract students of color so that they can be exposed to a variety of academic disciplines.

In miniature, the critical environmentalism project illustrates how institutional support, in the form of funds and reward structures, can help overcome institutional barriers and encourage collaborative and heterodox approaches. The research process created an important positive feedback loop between students and faculty; supported collaboration between faculty who did not work together before; honed a student's research and professional skills (e.g., public presentations); and created new information and resources. We see the process—across racial and tenure-line hierarchies, including undergraduate student mentorship—as itself an example of critical environmental work that both addresses a specific need while also working towards greater institutional accountability. It was important for the kinds of relationships that were built and the outcomes that were produced. But we are also aware that medium- or long-term, institutional changes must be made at a larger scale so that the burden of this work does not fall solely on individual projects.

As Serena Campbell’s words suggest, part of the positive feedback loop is faculty exposing students to critical environmental courses, internships, programs, and events. Students at UCSC are advocating for change. They have let their interest in interdisciplinary critical environmental courses, research, and networking opportunities be known, by calling on the university to make changes such as those outlined in this paper, and can now use this network to identify possible mentors and courses of interest. But, as described above, institutional responses to such pressures must be also substantial, involving dedication of time and resources, revision of course content and pedagogy, and a long-term commitment to supporting faculty who work on these issues. Such efforts will not only make environmental courses and majors more accessible to students from underrepresented backgrounds, but, to the extent that they transform the university and its assumptions about what environmentalism is, also enact epistemic justice.

Data availability

Not applicable.

References

Bhopal K (2017) Addressing racial inequalities in higher education: equity, inclusion and social justice. Ethn Racial Stud 40(13):2293–2299. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1344267

Braun B (2003) ‘On the raggedy edge of risk’ articulations of race and nature after biology. In: Moore DS, Kosek J, Pandian A (eds) Race, Nature, and the Politics of Difference. Duke University Press, North Carolina, pp 175–203

Brenner N (2009) What is critical urban theory? City 13(2–3):198–207

Churcher M (2022) Embodied institutions and epistemic exclusions: Affect in the academy. Topoi 41(5):895–904

Clarke V, Braun V (2013) Successful qualitative research: a practical guide for beginners, 1st edn. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Cole AG (2007) Expanding the field: revisiting environmental education principles through multidisciplinary frameworks. J Environ Educ 38(2):35–45. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOEE.38.1.35-46

Covarrubias R, Quinteros K (2023) UC Santa Cruz faculty of color exposing and reforming structures of whiteness in leadership. UC Hispanic-Serving Institutions Initiative. Oakland, CA

Cronin M, Alonzo S, Adamczak S et al (2021) Anti-racist interventions to transform ecology, evolution and conservation biology departments. Nat Ecol Evol 5:1213–1223

Cronon W (1996) The trouble with wilderness: or, getting back to the wrong nature. Environ Hist 1(1):7–28

Dare K (2021) Propelling UCSC undergraduates of color in environmental studies through mentorship. Senior thesis, University of California, Santa Cruz Environmental Studies Department

Dicochea P (2012) Discourses of race & racism within environmental justice studies: an eco-racial intervention. Ethnicity and Race in a Changing World: A Review Journal 17–28

Dotson K (2014) Conceptualizing epistemic oppression. Soc Epistemol 28(2):115–138

Ferreira F (2017) Critical sustainability studies: a holistic and visionary conception of socio-ecological conscientization. J Sustain Educ 13:1–22

Fischer K (2023) The insular world of academic research. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/the-insular-world-of-academic-research. Accessed 30 August 2023

Gold JR (2021) Scholars on the margins, or marginalized scholars? The (De) Valuation of Engaged Scholars as a Case of Epistemic Exclusion. Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Davis

Gould RK, Phukan I, Mendoza ME, Ardoin NM (2018) Panikkar B (2018) Seizing opportunities to diversify conservation. Conserv Lett 11:e12431. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12431

Guha R (1989) Radical American environmentalism and wilderness preservation: a third world critique. Environmental ethics, 1;11(1):71–83.

Horkheimer M (1982) Critical theory selected essays. Continuum Publishing, New York

Koscher E (2017) Whitewashed: the lack of diversity in environmental studies. The Columbia Spectator. https://www.columbiaspectator.com/the-eye/2017/11/21/whitewashed-the-lack-of-diversity-in-environmental-studies/. Accessed 20 April 2023

Latour B (1999) Pandora’s hope: essays on the reality of science studies. Harvard University Press

Lewis S, James K (1995) Whose voice sets the agenda for environmental education? Misconceptions inhibiting racial and cultural diversity. J Environ Educ 26(3):5–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.1995.9941440

Lövbrand E, Mobjörk M, Söder R (2020) The Anthropocene and the geo-political imagination: re-writing earth as political space. Earth Syst Gov 1(4):100051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esg.2020.100051

Lu F, Murai E (eds) (2023) Critical campus sustainabilities: bridging social justice and the environment in higher education. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature

Lu F, Hernandez Rosser R, Renteria A, Kim N, Erickson E, Sher A, O’Connor L (2018) Inclusive Sustainability: Environmental Justice in Higher Education. In: Leal Filho W, Marans RW, Callewaert J (eds) Handbook of Sustainability and Social Science Research. Springer, New York City, pp 63–81

Overland I, Sovacool B (2020) The misallocation of climate research funding. Energy Res Soc Sci 62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.101349

Pack C (2014) Privileged perspectives or diverse discourse? Disparities in student perceptions of and participation in the environmental movement at UCSC. Senior thesis, University of California, Santa Cruz Environmental Studies Department

Packer BL (2010) Romanticism. In: Petrulionis SH (ed) The Oxford Handbook of Transcendentalism. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 84–101

Pearson AR, Schuldt JP, Romero-Canyas R, Ballew MT, Larson-Konar D (2018) Diverse segments of the US public underestimate the environmental concerns of minority and low-income Americans. Proc Natl Acad Sci 115(49):12429–12434

Pepper D, Webster F, Revill G (eds) (2003) Environmentalism: critical concepts (Vol. 1–4). Taylor & Francis

Purdy J (2015) After nature: a politics for the Anthropocene. Harvard University Press

Reti IH, Vanderscoff C, Rabkin, S (2020) Seeds of something different: an oral history of the University of California, Santa Cruz--Volume 1. UC Santa Cruz Library. UC Santa Cruz: Regional History Project Oral Histories. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/68v4q9sf. Accessed 20 December 2022

Roshanravan S (2014) Motivating coalition: Women of color and epistemic disobedience. Hypatia 29(1):41–58

Settles IH, Buchanan NT, Dotson K (2019) Scrutinized but not recognized:(In) visibility and hypervisibility experiences of faculty of color. J Vocat Behav 113:62–74

Settles IH, Warner LR, Buchanan NT, Jones MK (2020) Understanding psychology’s resistance to intersectionality theory using a framework of epistemic exclusion and invisibility. J Soc Issues 76(4):796–813

Settles IH, Jones MK, Buchanan NT, Brassel ST (2022) Epistemic exclusion of women faculty and faculty of color: understanding scholar (ly) devaluation as a predictor of turnover intentions. The Journal of Higher Education 93(1):31–55

Strang V (2007) Integrating the social and natural sciences in environmental research: a discussion paper. Environ Dev Sustain 11:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-007-9095-2

Taylor D (2007) Diversity and equity in environmental organizations: the salience of these factors to students. J Environ Educ 39(1):19–44. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOEE.39.1.19-44

Taylor D (2018) Enhancing racial diversity in the association for environmental studies and sciences. J Environ Stud Sci 8:379–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-018-0518-1

Taylor A, Hernandez A, Peterson A, Jinnah S (2022) Faculty diversity in California environmental studies departments: implications for student learning. J Environ Stud Sci 12:490–504

University of California (2020) UC employee headcount. https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/about-us/information-center/uc-employee-headcount. Accessed 20 April 2023

Walker PA (2007) Political ecology: where is the politics? Prog Hum Geogr 31(3):363–369

Funding

This project received funding from the Building Belonging program at the Institute of Social Transformation at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, F., Murai, E., Campbell, S. et al. Building more epistemically inclusive and environmentally equitable universities. J Environ Stud Sci (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-024-00935-z

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-024-00935-z