Abstract

Recent studies point to the cannabinoid CB2 receptors (CB2r) and the non-cannabinoid receptor GPR55 as potential key targets involved in the response to stress, anxiety, and depression. Considering the close relationship between neuropsychiatric disorders and suicide, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the potential alterations of CB2r and GPR55 in suicide victims. We analyzed gene and protein expression of both receptors by real-time PCR and western blot, respectively, in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) of 18 suicide victims with no clinical psychiatric history or treatment with anxiolytics or antidepressants, and 15 corresponding controls. We used in situ proximity ligation assay to evaluate whether the receptors formed heteromeric complexes and to determine the expression level of these heteromers, also assessing the co-expression of heteromers in neurons, astroglia, or microglia cells. CB2r and GPR55 gene expressions were significantly lower (by 33 and 41%, respectively) in the DLPFC of suicide cases. CB2r protein expression was higher, as were CB2-GPR55 heteroreceptor complexes. The results also revealed the presence of CB2-GPR55 receptor heteromers in both neurons and astrocytes, whereas microglial cells showed no expression. We did not observe any significant alterations of GPR55 protein expression. Additional studies will be necessary to evaluate if these alterations are reproducible in suicide victims diagnosed with different psychiatric disorders. Taken together, the results suggest that CB2r and GPR55 may play a relevant role in the neurobiology of suicide.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Suicide is a devastating public health problem. According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), it is the 13th leading cause of death, with 800,000 people taking their own life every year. Multiple factors are associated with an increased risk of suicide, including recent exposure to traumatic events, stressful stimuli, mood disorders, and drug use disorders. These data support the need for greater investments and efforts to develop new preventive strategies, including early detection of mental illnesses and better identification of the neurobiological mechanisms involved in suicidal behavior.

Several postmortem studies have identified alterations in the monoaminergic system, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA), and in neurotrophic factors in suicide victims [1,2,3]. Recently, the endocannabinoid system (ECS) has emerged as a potential target due to its involvement in the regulation of emotional response.

Initially, a large number of studies focused on examining the role of cannabinoid CB1 receptors (CB1r) due to their high expression in the central nervous system (CNS) [4]. Genetic and pharmacological studies in rodents showed that these receptors play a crucial role in the response to stress, anxiety, and depression [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. A higher frequency of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) of the CB1r gene (CNR1) was also observed in major depressive [13, 14] and schizophrenic patients [15]. Furthermore, polymorphisms of the CNR1 gene were considered a risk factor for depression in Parkinson’s disease [16]. Postmortem studies have also suggested an association between suicide and a higher density of CB1r [17, 18] and CB1r-mediated G-protein activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) [18, 19]. However, other studies failed to observe any alteration in CB1r immunodensity [20] nor in CB1r function [17]. These discrepancies may be due to the type of samples included in the studies (suicide schizophrenic patients [20], suicide depressive patients [18], and suicide alcoholic patients [13, 19]).

The identification of cannabinoid CB2 receptors (CB2r) in several regions of the brain has pointed to its potential role in the CNS [21,22,23]. In this respect, CB2r appears to be a promising novel target for managing mood disorders. Transgenic mice overexpressing CB2r in the CNS (CB2xP) presented an endophenotype resistant to acute and chronic anxiogenic- and depressogenic-like stimuli [21, 24]. These marked behavioral features were associated with pronounced alterations in key targets related to the response to stress, anxiety, and depression; inter alia components in the HPA axis; the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF); and GABAAα2 and GABAAγ2 receptor subunits [21, 24]. In contrast, mice lacking CB2r (CB2−/−) presented high vulnerability to stressful stimuli [25]. Moreover, an association between cannabinoid CB2R polymorphism Q63R and depression was detected in a Japanese population [26]. Pharmacological studies revealed that chronic administration of the cannabinoid CB2r-antagonist AM630 resulted in anxiolytic- and antidepressant-like effects that were associated with increased gene expression of CB2r, BDNF, GABAAα2, and GABAAγ2 subunits in the cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus [27, 28]. In contrast, administration of the cannabinoid CB2r-agonist JWH133 produced the opposite behavioral and neurochemical effects [28]. Taken together, these results strongly support a relevant role for CB2r in regulating anxiety and depression.

Recently, the G-protein-coupled receptor 55 (GPR55) has been proposed as an additional target of endocannabinoids [29]. This type of receptor is mainly expressed in peripheral tissues, including adrenal tissue, spleen, and ileum [29]. In addition, GPR55 is expressed in several brain regions, including caudate, putamen, striatum, hippocampus, and nucleus accumbens [30]. Different studies suggest that GPR55 may represent a novel approach for treating cancer [31,32,33], metabolic disorders [34,35,36], and neuropathic/inflammatory pain [37, 38]. However, the functional significance of GPR55 in the CNS remains unclear. Preliminary results show alterations in GPR55 gene expression induced by early-life stress in mice [39], while intracerebroventricular administration of the GPR55 agonist O-1602 revealed an anxiolytic action that was blocked by the previous administration of the GPR55 receptor antagonist ML-193 [40]. Furthermore, stimulation of GPR55 increases presynaptic neurotransmitter release in the hippocampus [41, 42].

Given the close relationship between these receptors and emotional response, exploring their role in suicide is of special relevance. To this aim, we examined the gene and protein expression of CB2r and GPR55 in the DLPFC of suicide victims without clinical psychiatric history or pharmacological treatment with anxiolytics or antidepressants. We used in situ proximity ligation assay (PLA) to evaluate if both receptors formed heteromers in this brain region. In addition, we measured the expression of CB2-GPR55 receptor heteromers and evaluated the type of cells (neurons, astroglia, or microglia) where these heteromers are expressed.

Methods

Subjects

Brain samples were obtained from autopsy material derived from the Institute of Legal Medicine in accordance with the agreement signed between the Miguel Hernandez University of Elche, the Institute of Legal Medicine of Alicante, and the Department of Justice of the Valencian Regional Government for analyzing brain samples from autopsies. The local ethics committee approved the collection of tissues.

Table 1 presents demographic and postmortem data for included subjects, who were all white and came from the Spanish region of Alicante. Dissection of DLPFC was performed in 18 male suicide victims (S) and 15 controls (C), matched as closely as possible for age (C 46 ± 12 years, range 19 to 64; S 43 ± 17 years, range 18 to 78) and postmortem interval (PMI, C 15 ± 7 h; S 17 ± 5 h). We also took into account the time from death until the introduction of the corpse into a refrigerated chamber (4 °C), or the postmortem interval until refrigeration (PMR) (C 3.28 ± 2.14 h; S 3.89 ± 2.46 h). We excluded individuals with a history of cerebral trauma, central nervous system disease, chronic alcoholism, or illicit or therapeutic drug use. Bodily fluids (blood, bile, aqueous humor, and urine) were toxicologically screened for cocaine, opiates, alcohol, antidepressants, and other acidic and basic drugs, and samples testing positive were excluded. We also excluded controls and suicide subjects who met criteria for any psychiatric disorder diagnosis during their lifetime according to close relatives, forensic psychological assessment, and the clinical history of each subject. All cases in which the clinical history of the subject was not available were not included in the study. Brain samples were coded to mask the investigators to the cause of death.

Brain Dissection

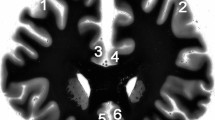

We obtained brains 15 to 17 h after death (15 ± 7 h and 17 ± 5 h for controls and suicide, respectively). After removal from the skull, brains were carefully dissected according to Brodmann’s Atlas. The DLPFC (Brodmann area 9) was dissected by a fine microdissecting Graefe’s knife, the white matter removed, and tissues immediately returned to − 70 °C until further use.

RNA Integrity Number Evaluation

All total RNA samples from DLPFC were analyzed to find out the RNA integrity number (RIN). RNA quality level evaluation is necessary to obtain reliable gene expression results by real-time qPCR analyses [43]. Briefly, total RNA was isolated from DLPFC snap frozen tissue using TRI Reagent (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Subsequently, we used the 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Madrid, Spain) to analyze the integrity of the RNA samples according to the RNA ribosomic bands detected (18S and 28S). Depending on the ratio 28S/18S, we calculated a value of 1 to 10, called the RNA integrity number (RIN), as a measure of RNA degradation (with lower values expressing greater degradation). The electropherograms and gel images representative of DLPFC are shown in Fig. 1(A). The mean RIN value for the RNA samples of C and S subjects is higher than 6 (C 6.26 ± 0.42; S 6.35 ± 0.4), which represents good quality RNA for gene expression analyses (Fig. 1(B)) [44]. RIN values for each sample are detailed in Table 1.

CB2r A isoform and GPR55 gene expression analyses in the DLPFC of suicide victims by real-time PCR. (A. and B.) Total RNA integrity number (RIN) evaluation in the DLPFC of suicide victims and control subjects: (A.) Representative electropherogram images of mean RIN values from DLPFC, (B.) RIN values summary table, gray boxes contain global mean values ± SEM. (C.) Relative gene expression of CB2r A isoform and (D.) GPR55 gene expression in DLPFC of suicide victims (n = 18) and their corresponding control group (n = 15). Asterisks indicate values from suicide victims that are significantly different (p < 0.05) from control subjects. Columns represent the mean and the vertical line ± the standard error of the mean (SEM) of 2-ΔΔCt

Real-time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis of the CB2r A Isoform and GPR55

Relative gene expression analyses of CB2r and GPR55 in DLPFC were carried out in C and S. Total RNA was obtained from brain sections using Tri Reagent extraction reagent (Applied Biosystems, Madrid, Spain). After DNAse digestion, reverse transcription was performed following manufacturer instructions (Epicenter, Tech. Corp., Madison, Wisconsin). Relative CB2r A isoform and GPR55 gene expression levels were measured using Taqman Gene Expression Assays (CB2r A isoform primer pair and probe were as follows: forward, GGAAGAAAGAGAATATTGTTCAGTTGATT, reverse, GCTGGCCTTGGAGAGTGACA, MGB Taqman probe, CCAGATGCAGCCGC; GPR55 Mm02621622_m1) [45] as a double-stranded DNA-specific fluorescent dye and performed on the StepOne Sequence Detector System (Applied Biosystems, Madrid, Spain). In this study, two housekeeping genes, cyclophilin (PPIA, Hs99999904_m1) and synaptophysin (SYP, Hs00300531_m1), were used to ensure the validity and reproducibility of results. All reagents were obtained from Applied Biosystems, and manufacturer protocols were followed. All primer-probe combinations were optimized and validated for relative quantification of gene expression. Briefly, data for each target gene were normalized to the endogenous reference genes, and the fold change in target gene abundance was determined using the 2-ΔΔCt method [46], so that suicide case levels were expressed relative to control subject levels. For each sample, we express the results as the mean obtained with each endogenous housekeeping gene (PPIA and SYP).

Immunoblot Analysis of the CB2 and GPR55 Receptors

The relative CB2r and GPR55 protein expressions between C and S were measured from frozen brain tissue, dissected and homogenized in TRIS buffer (10 Mm Tris-HCl) containing 100 Mm dithiothreitol (DTT), Nonidet 0.2% and freshly added protease inhibitor cocktail. After sonication (20 pulses), the homogenate was centrifuged at 14,000 g for 20 min, and the resulting supernatant was isolated, made into aliquots, and stored at − 80 °C until the assay. The protein content of each supernatant aliquot was determined by Lowry’s method [47] using standard bovine serum albumin (BSA). After determining and adjusting protein levels (30 μg, 25 μl), homogenates of DLPFC tissues were mixed with Laemmli sample buffer (5 μl; SDS 10%, distilled H2O, glycerol 50%, Tris HCl 1 M pH 6.8, dithiothreitol and blue bromophenol) containing β-mercaptoethanol (50 μL per mL of Laemmli), denaturalized (98 °C, 10 min), and centrifuged. Samples were loaded into a polyacrylamide gel (10%), and proteins separated by molecular weight and then blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Acefesa, Barcelona, Spain) overnight using the wet transfer system (Biorad). The membrane was treated with blocking buffer (TTBS 10 mM Tris-HCl, 0.9% NaCl, 20% Tween 20 containing 1% milk powder) for 1 h at room temperature and 2 h at 4 °C. The membrane was incubated with a specific primary antibody against CB2r (Cayman Chemical, Michigan, USA; 1:300 dilution) or GPR55 (Cayman Chemical, Michigan, USA; 1:100 dilution) overnight at 4 °C. Proteins recognized by the anti-rabbit IgG peroxidase-linked secondary antibody were detected using the ECL kit according to manufacturer instructions (Amersham, Madrid, Spain) and visualized on the DNR Bio-Imager (DNR Bio-Imaging Systems Ltd., Jerusalem, Israel). Developing images were quantified by densitometry (program Image 4 Gauge, Fujifilm), and exposures were analyzed repeatedly to ensure the linearity of the band intensities. All densitometries were expressed in arbitrary units (A.U.). In all western blot analyses, the housekeeping gene GAPDH (Sigma, Madrid, Spain) and β-actin (Sigma, Madrid, Spain) were used as loading controls.

In Situ Proximity Ligation Assays

We performed proximity ligation assays (PLAs) to analyze potential CB2r-GPR55 molecular interactions and to identify the cell types where they were expressed.

The PLA technique was carried out in paraformaldehyde-fixed human brain cortex sections. Proximity probes consisted of affinity-purified antibodies modified by covalent attachment of the 5′ end of oligonucleotides. To create our PLA probes, we conjugated a rabbit anti-CB2 receptor antibody (101550, Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, USA) with a PLUS oligonucleotide (Duolink In Situ Probemaker PLUS DUO92009, Sigma-Aldrich Co, St. Louis, USA) and a rabbit anti-GPR55 antibody (10224, Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, USA) with a MINUS oligonucleotide (Duolink In Situ Probemaker MINUS DUO92010, Sigma-Aldrich Co, St. Louis, USA), following manufacturer instructions. We assessed the presence of receptor-receptor molecular interactions in the samples using the Duolink II in situ PLA detection kit (Duolink In Situ Detection Reagents Red, DUO92008, developed by Olink Bioscience, Uppsala, Sweden; and now distributed by Sigma-Aldrich as Duolink using PLA technology). Briefly, 30-μm DLPFC sections were obtained using a cryostat (CM3050 S, Leica Microsystems, Mannheim, Germany). Sections were collected in cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and immediately mounted on Superfrost Plus glass slides (4951PLUS, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, USA). Sections were washed in PBS-glycine 20 mM, permeabilized using PBS-glycine 20 mM containing 0.05% Triton X-100 for 15 min, and finally washed in PBS-glycine 20 mM. Sections were then incubated in a preheated humidity chamber for 1 h at 37 °C with the blocking solution and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the PLA probe-conjugated antibodies (1:100 dilution for both antibodies) and with Hoechst (1:50, B1155, Sigma-Aldrich Co, St. Louis, USA) for nuclear staining. After washing in buffer A (NaCl 0.15 M, tris-base 0.01 M, Tween-20 0.05%, pH 7.4) at room temperature, sections were incubated with the ligation solution for 1 h at 37 °C in a humidity chamber. Sections were again washed and subsequently incubated with the amplification solution for 100 min at 37 °C in a humidity chamber and then washed in buffer B (NaCl 0.1 M, Tris-base 0.035 M, Tris-HCl 0.165 M, ph 7.5). Finally, samples were mounted using Mowiol (475904, Calbiochem, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). To check for non-specific labeling and amplification, we performed negative controls using only the rabbit anti-CB2 receptor antibody linked to the PLUS or the rabbit anti-GPR55 receptor antibody linked to the MINUS oligonucleotide, combined with an anti-goat secondary antibody linked to the MINUS (Duolink In Situ PLA Probe anti-Goat MINUS, DUO92006, Sigma-Aldrich Co, St. Louis, USA) or PLUS (Duolink In Situ PLA Probe anti-Goat PLUS DUO92003, Sigma-Aldrich Co, St. Louis, USA) oligonucleotide, respectively.

We inspected stained samples under a Leica SP2 confocal laser-scanning microscope (Leica Microsystems, Mannheim, Germany). To ensure appropriate visualization of the labeled elements and to avoid false positive results, the emission following excitation with the laser at 561 nm was filtered through a band pass filter of 576–648 nm and color coded in red. Finally, a long pass filter of ultraviolet laser at 406–501 nm was used to visualize the emission from the laser at 364 nm and color-coded in blue. Statistical analyses on the CB2-GPR55 receptor heteromer expression were conducted using dedicated software known as Duolink ImageTool (ref DUO90806, Sigma-Olink). This software was developed for quantifying PLA signals and cell nuclei in images generated from fluorescence microscopy. Briefly, for each field and channel (one for CB2/GPR55 receptor PLA stain and another one for Hoechst or TOPRO-3; see figure legends: stain), images from 15 Z stacks with a step size of 0.43 μm were acquired with the 63× oil-immersion lens (N.A. 1.30).

To properly assess the identities of cortical cells expressing GB2-GPR55 heteromers, a number of markers were used to ascertain different populations of glial cells. In all cases, the PLA technique was carried out first, followed by the immunofluorescent stain of astrocytes and microglial cells. Astrocytes were detected using a rabbit anti-GFAP primary antibody (1:400; ref. Z0334, Dako) followed by an Alexa488-coupled donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:200; ref. A-21206, Thermo Scientific). A rabbit anti-Iba1 primary antibody (1:500; ref. 019–19741, Wako) was used to disclose microglial cells, followed by an Alexa488-coupled donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:200). Once the stainings were complete, samples were mounted using an aqueous mounting medium. Appropriate negative control assays were performed to ensure the lack of non-specific labeling and amplification.

Statistical Analyses

We performed statistical analyses of the results using the Student’s t test to compare S and C groups. Pearson product moment correlation was used to rule out potential correlations between RIN, PMR, and PMI, on the one hand, and the results of gene expression studies, on the other. We used SigmaStat software (Systat Software Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for all analyses and considered differences to be significant if the probability of error was less than 5%.

Results

CB2r A Isoform and GPR55 Gene Expression Levels in DLPFC: Real-time PCR Analysis

Quantitative PCR studies showed significantly lower levels of CB2r A isoform gene expression in the DLPFC of S (n = 18) compared to C (n = 15) (Fig. 1(C); − 33%; Student’s t test: t = 2.376, p = 0.024, 31 df). GPR55 gene expression was also significantly lower in the DLPFC of S cases (Fig. 1(D); − 41%; Student’s t test: t = 6.259, p < 0.001, 31 df). Results were confirmed using two distinct housekeeping genes (cyclophilin and synaptophysin).

In addition, we employed a Pearson product moment correlation to obtain a correlation coefficient between RIN, PMR, and PMI, on the one hand, and gene expression values for CB2r and GPR55 of C and S cases, on the other. There was no correlation between any of these parameters and gene expression values. Furthermore, we also analyzed the correlation coefficient between age and gene expression values for CB2r and GPR55 in C and S cases, observing no significant association (Table 2).

CB2r and GPR55 Protein Expression in DLPFC: Western Blotting Analysis

Western blotting experiments were carried out to analyze CB2r and GPR55 in the DLPFC of S (n = 18) and their corresponding control group (n = 15). CB2r protein expression was significantly higher (Fig. 2(A); 33%; Student’s t test: t = − 2.992, p = 0.005, 31 df). We did not observe significant differences in GPR55 protein expression between groups (Fig. 2(B); Student’s t test: t = 0.122, p = 0.90, 31 df).

Protein expression analyses of CB2r and GPR55 in DLPFC suicide victims by western blot. (A.) Protein expression levels of CB2r and (B.) GPR55 in DLPFC of suicide victims (n = 18) and their corresponding control group (n = 15). Representative immunoblots of (C.) CB2r and (D.) GPR55 protein expression. Asterisks indicate values from suicide victims that are significantly different (p < 0.05) from control subjects. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of arbitrary units (A.U)

Analysis of Potential CB2-GPR55 Molecular Interactions: In Situ PLA

To test for the presence of CB2-GPR55 receptor complexes in situ, we performed a PLA in sections of DLPFC taken from necropsies. The assay identifies two proteins separated by less than 17 nm; in the last 5 years, PLA has been optimized to detect GPCR heteromers in natural sources [48,49,50]. Punctate red spots detected by confocal microscopy in Hoechst-nuclei stained cells indicated the occurrence of CB2-GPR55 receptor heteromers in human sections (Fig. 3). The software used for analysis highlights the specific signal in white for better observation of the results, especially those yielded at low magnification levels. Accordingly, the data on the left (white dots, Fig. 3(A) and (C)) and central panels (red dots, Fig. 3(A’) and (C’)) of Fig. 3 are identical. This staining was not observed in negative controls, performed omitting one of the primary antibodies (Fig. 3(D)).

CB2-GPR55 receptor heteromer expression in human prefrontal cortex. In situ proximity ligation assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods using control (A, A’, A”) and suicidal (C, C’, C”) human brain sections. A” and C” are magnification images of fields (white-dotted rectangles) in, respectively, A’ and C’. Confocal microscopy images (superimposed sections) are shown; heteromers appear as red clusters and Hoechst-stained nuclei appear in blue. (B) Shows the ratio (number of red spots/cell-containing spots) for the indicated samples. Data are the mean ± SEM of counts in 5–7 different fields (each image covered an area of 59,692 μm2) from every sample from controls (n = 7) or suicidal (n = 6). Student’s t test analysis showed significant inter-group differences on ratio of PLA spots. Asterisks indicate values from suicide victims that are significantly different (p < 0.05) from control subjects. (D) A negative control obtained by omitting one of the primary antibodies is shown. Scale bars: 50 μm (A, A’, C, C′), 10 μM (A”, C”)

We compared PLA results obtained in sections from suicide cases with those obtained from controls. We selected ad hoc parameters for cell size, and the software depicted the contour of the cell (light green in panels (A) and (C) of Fig. 3) with the perimeter parameters used for calculating dot/cell ratios (only taking into account cells that contain dots). In both sample types, CB2-GPR55 heteroreceptor complexes were detectable, and the number of red spots in positive cells was notable. The number of dots per cell was markedly and significantly higher in the samples derived from the S group (Fig. 3(B); Student’s t test: t = 3.03, p = 0.003, 11 df).

Cortical Cells Expressing CB2-GPR55 Receptor Heteromers: In Situ PLA

The combination of the PLA together with the immunofluorescent detection of glial cells revealed the presence of CB2-GPR55 receptor heteromers in both astrocytes and neurons (Fig. 4 panel (1A)–(D), panel (3A)–(F)), whereas microglial cells completely lacked these receptor heteromeric complexes (Fig. 4 panel (2A)–(D)). Although we also observed the presence of CB2r-GPR55 receptor heteromers in neurons and astrocytes, we consistently found more receptors in layer V neurons (Fig. 4, panel (3A)–(E)). It is worth noting that astrocytes, despite their relatively small cytoplasmic compartment, showed a very intense expression of CB2r -GPR55 receptor heteromers.

In situ proximity ligation-based detection of cellular types expressing CB2-GPR55 receptor heteromers. Panel 1A–1D: Expression of CB2-GPR55 receptor heteromers (PLA-detected, red channel) in astrocytes (GFAP immunostain; green channel). TOPRO3-counterstain was used to disclose cell nuclei. 1B and 1D are insets taken from 1A and 1C, respectively, to illustrate the expression of CB2r-GPR55 receptor heteromers in astrocytes. Cortical neurons also expressed heteromeric complexes made of CB2r and GPR55 receptors. Panels 1A–1B were taken from control samples whereas panels 1C–1D belong to suicide cases. Panel 2A–2D: Expression of CB2r-GPR55 receptor heteromers (PLA-detected, red channel) in microglial cells (Iba1 immunostain; green channel). TOPRO3-counterstain was used to disclose cell nuclei. 2B and 2D are insets taken from 2A and 2B, respectively, to properly illustrate the expression of CB2r-GPR55 receptor heteromers in microglial cells. Cortical neurons also expressed heteromeric complexes made of CB2r and GPR55 receptors. Panels 1A–1B were taken from control samples whereas panels 2C–D belong to suicide cases. Scale bars are 800 μm for low-magnification panels and 10 μm for insets. Panel 3A–3D: Identification of CB2r-GPR55 receptor heteromers in layer V cells of the PFC cortex of control samples (3A–3C) and suicide patients (3D–3F). CB2r-GPR55 heteromers were observed both in neurons (labeled as N) as well as in glial cells (G; presumed astrocytes). Scale bar is 10 μm in all panels

Discussion

The results of the present study provide crucial information regarding the potential role of CB2r and GPR55 in suicide. This assumption is supported by the following observations: (1) CB2r and GPR55 gene expression was reduced in the DLPFC of suicide victims, (2) CB2r protein expression was increased in the DLPFC of suicide victims, (3) the expression of CB2-GPR55 heteromers was identified in neurons and astrocytes, and finally, (4) we found increased expression of CB2-GPR55 heteromers in the DLPFC of suicide victims.

In recent years, the ECS has become relevant to understanding suicidal behavior due to its involvement in different psychiatric disorders such as depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. Early studies focused on determining potential alterations of CB1r in suicide victims. An increase of CB1r protein expression and CB1r mediated GTP binding were observed in the DLPFC of both depressive-suicide victims [18] and alcoholic-suicide victims [19], suggesting that these alterations are related with suicidal behavior.

In this study, we further explored the role of the ECS in suicide by analyzing the gene and protein expression of CB2r and GPR55 in the DLPFC of suicide victims. Most postmortem studies that have focused on identifying different key targets underlying suicidal behavior have been carried out in depressive-suicide victims. Pharmacological treatment of depressive disorders is complex, and patients are treated daily with anxiolytic and/or antidepressant drugs. Therefore, the results from these postmortem studies may be distorted by the effects of long-term antidepressant treatment. In fact, it is difficult to know if the findings are a consequence of the antidepressant treatment itself. For these reasons, we examined CB2r and GPR55 in suicide victims who had not been diagnosed with mental illness at the time of death and were not on any specific neuropsychiatric treatment. Furthermore, toxicological analyses showed all samples to be free of any substance of abuse. All the brain samples examined in the present study were well matched, as closely as possible, regarding age, PMI, and RIN.

The analysis of the data presented here clearly revealed a significant reduction of CB2r and GPR55 gene expression in the DLPFC of S compared with C. On the other hand, CB2r protein was significantly higher, and there was no significant difference between groups in GPR55 protein expression. The discrepancy between gene and protein alterations may be due to compensatory changes affecting the half-life of mRNA and the protein turnover. Differences are not always equivalent in the regulation of translational and post-translational machinery or in changes at the cellular levels of an individual gene and its corresponding protein.

These results are consistent with previous studies in rodents carried out by our group and others demonstrating that the lack of CB2r was associated with increased vulnerability to anxiogenic- and depressogenic-like disorders [25] and synaptic plasticity alterations [51, 52]. Interestingly, the overexpression of CB2r in the central nervous system protects against anxiety [24] and mood-related disorders in mice [21]. Furthermore, cannabidiol, one of the main compounds present in Cannabis sativa, that lacks addictive properties and presents anxiolytic, antidepressant, antipsychotic, and neuroprotective properties, blocks GPR55 receptors and may act as a cannabinoid CB2r inverse agonist or antagonist [53,54,55,56]. Altogether, these data further support potential roles of CB2r and GPR55 in modulating emotional states.

DLPFC plays a crucial role in decision-making and cognitive functions. Dysfunctions in the DLPFC of patients who attempted suicide are associated with impaired executive functions and increased impulsivity [57, 58]. Impulsive behaviors are closely related with increased susceptibility to suicide [59, 60]. Considering the association between impaired decision-making and suicide, the alterations of CB2r and GPR55 expression observed in the DLPFC of suicide victims suggest a potential involvement of these receptors in the control of decision-making.

Most recently, a growing body of evidence suggests that the heteromerization of G-protein-coupled-receptors (GPCRs) represents a fundamental aspect of receptor biology, affecting function, trafficking, and pharmacology. Using PLA [61], we demonstrated that CB2r and GPR55 are co-expressed and form heteromers in neurons and astrocytes in human DLPFC. To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify CB2/GPR55 heteromers in the CNS. Previous studies reported that CB1r and CB2r [62], as well as CB1r and GPR55 receptor heteromers [63], are expressed in basal ganglia of macaques and in rat and monkey striatum, respectively. An increase of CB2-GPR55 heteromers was detected in the DLPFC of suicide victims. Although further studies are needed to elucidate the biological and pharmacological properties of CB2-GPR55 heteromers, these results suggest a close cooperation between both types of receptors. Heterodimerization may stabilize CB2r, explaining the increase in protein even though its messenger RNA is less abundant. Moreover, we cannot rule out the possibility that the observed alterations might be due to the expression of heteromers and CB2r in different cell types in suicide versus control cases. These findings may represent an opportunity to stimulate the development of further studies designed to evaluate the role of these heteromers in suicide. The availability of drugs acting on CB2r and/or GPR55 enables an evaluation of the potential pre-clinical and clinical efficacy of the pharmacological manipulation of both targets in preventing suicide in individuals at risk.

Limitations

Additional studies will be necessary to evaluate if these alterations are reproducible in suicide victims diagnosed from different psychiatric disorders.

Conclusions

In summary, our results suggest a potential association between CB2r and GPR55 and suicide. The alterations in CB2r and GPR55 receptor gene and protein expression in brain areas related with the control of decision-making point out CB2r and GPR55 as potential targets involved in the impulsivity associated with suicidal behavior. Indeed, the identification of CB2-GPR55 heteromers might be a major step ahead for the improvement of pharmacological management of suicide. Further studies in additional brain areas are necessary to explore the role of CB2-GPR55 heteromers in the neurobiology of suicide.

References

Furczyk K, Schutova B, Michel TM, Thome J, Buttner A. The neurobiology of suicide—a review of post-mortem studies. Journal of molecular psychiatry, 2013; 1(1), 2.

Sokolowski M, Wasserman J, Wasserman D. An overview of the neurobiology of suicidal behaviors as one meta-system. Molecular psychiatry, 2015; 20(1), 56–71.

Turecki G. The molecular bases of the suicidal brain. Nature reviews, 2014; 15(12), 802–816.

Herkenham M, Lynn AB, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, de Costa BR, Rice KC. Characterization and localization of cannabinoid receptors in rat brain: a quantitative in vitro autoradiographic study. J Neurosci, 1991; 11(2), 563–583.

Steiner MA, Wanisch K, Monory K et al. Impaired cannabinoid receptor type 1 signaling interferes with stress-coping behavior in mice. The pharmacogenomics journal, 2008; 8(3), 196–208.

Uriguen L, Perez-Rial S, Ledent C, Palomo T, Manzanares J. Impaired action of anxiolytic drugs in mice deficient in cannabinoid CB1 receptors. Neuropharmacology, 2004; 46(7), 966–973.

Cota D, Steiner MA, Marsicano G et al. Requirement of cannabinoid receptor type 1 for the basal modulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function. Endocrinology, 2007; 148(4), 1574–1581.

Zarruk JG, Fernandez-Lopez D, Garcia-Yebenes I et al. Cannabinoid type 2 receptor activation downregulates stroke-induced classic and alternative brain macrophage/microglial activation concomitant to neuroprotection. Stroke, 2011;

Aso E, Ozaita A, Valdizan EM et al. BDNF impairment in the hippocampus is related to enhanced despair behavior in CB1 knockout mice. J Neurochem, 2008; 105(2), 565–572.

Shearman LP, Rosko KM, Fleischer R et al. Antidepressant-like and anorectic effects of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor inverse agonist AM251 in mice. Behav Pharmacol, 2003; 14(8), 573–582.

Tzavara ET, Davis RJ, Perry KW et al. The CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716A selectively increases monoaminergic neurotransmission in the medial prefrontal cortex: implications for therapeutic actions. Br J Pharmacol, 2003; 138(4), 544–553.

Witkin JM, Tzavara ET, Davis RJ, Li X, Nomikos GG. A therapeutic role for cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonists in major depressive disorders. Trends in pharmacological sciences, 2005; 26(12), 609–617.

Monteleone P, Bifulco M, Maina G et al. Investigation of CNR1 and FAAH endocannabinoid gene polymorphisms in bipolar disorder and major depression. Pharmacol Res, 2010; 61(5), 400–404.

Mitjans M, Serretti A, Fabbri C et al. Screening genetic variability at the CNR1 gene in both major depression etiology and clinical response to citalopram treatment. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 2013; 227(3), 509–519.

Bae JS, Kim JY, Park BL et al. Genetic association analysis of CNR1 and CNR2 polymorphisms with schizophrenia in a Korean population. Psychiatric genetics, 2014; 24(5), 225–229.

Barrero FJ, Ampuero I, Morales B et al. Depression in Parkinson’s disease is related to a genetic polymorphism of the cannabinoid receptor gene (CNR1). The pharmacogenomics journal, 2005; 5(2), 135–141.

Erdozain AM, Rubio M, Valdizan EM et al. The endocannabinoid system is altered in the post-mortem prefrontal cortex of alcoholic subjects. Addict Biol, 2015; 20(4), 773–783.

Hungund BL, Vinod KY, Kassir SA et al. Upregulation of CB1 receptors and agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPgammaS binding in the prefrontal cortex of depressed suicide victims. Molecular psychiatry, 2004; 9(2), 184–190.

Vinod KY, Arango V, Xie S et al. Elevated levels of endocannabinoids and CB1 receptor-mediated G-protein signaling in the prefrontal cortex of alcoholic suicide victims. Biol Psychiatry, 2005; 57(5), 480–486.

Uriguen L, Garcia-Fuster MJ, Callado LF et al. Immunodensity and mRNA expression of A2A adenosine, D2 dopamine, and CB1 cannabinoid receptors in postmortem frontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia: effect of antipsychotic treatment. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 2009; 206(2), 313–324.

Garcia-Gutierrez MS, Perez-Ortiz JM, Gutierrez-Adan A, Manzanares J. Depression-resistant endophenotype in mice overexpressing cannabinoid CB(2) receptors. British journal of pharmacology, 2010; 160(7), 1773–1784.

Onaivi ES, Ishiguro H, Gong JP et al. Discovery of the presence and functional expression of cannabinoid CB2 receptors in brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2006; 1074, 514–536.

Gong JP, Onaivi ES, Ishiguro H et al. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors: immunohistochemical localization in rat brain. Brain research, 2006; 1071(1), 10–23.

Garcia-Gutierrez MS, Manzanares J. Overexpression of CB2 cannabinoid receptors decreased vulnerability to anxiety and impaired anxiolytic action of alprazolam in mice. J Psychopharmacol, 2011; 25(1), 111–120.

Ortega-Alvaro A, Aracil-Fernandez A, Garcia-Gutierrez MS, Navarrete F, Manzanares J. Deletion of CB2 cannabinoid receptor induces schizophrenia-related behaviors in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology, 2011; 36(7), 1489–1504.

Onaivi ES, Ishiguro H, Gong JP et al. Brain neuronal CB2 cannabinoid receptors in drug abuse and depression: from mice to human subjects. PLoS ONE, 2008; 3(2), e1640.

Garcia-Gutierrez MS, Garcia-Bueno B, Zoppi S, Leza JC, Manzanares J. Chronic blockade of cannabinoid CB(2) receptors induces anxiolytic-like actions associated to alterations in GABA(A) receptors. Br J Pharmacol, 2011;

Garcia-Gutierrez MS, Perez-Ortiz JM, Gutierrez-Adan A, Manzanares J. Depression-resistant endophenotype in mice overexpressing cannabinoid CB(2) receptors. Br J Pharmacol, 160(7), 1773–1784.

Ryberg E, Larsson N, Sjogren S et al. The orphan receptor GPR55 is a novel cannabinoid receptor. British journal of pharmacology, 2007; 152(7), 1092–1101.

Sawzdargo M, Nguyen T, Lee DK et al. Identification and cloning of three novel human G protein-coupled receptor genes GPR52, PsiGPR53 and GPR55: GPR55 is extensively expressed in human brain. Brain research. Molecular brain research, 1999; 64(2), 193–198.

Pineiro R, Maffucci T, Falasca M. The putative cannabinoid receptor GPR55 defines a novel autocrine loop in cancer cell proliferation. Oncogene, 2011; 30(2), 142–152.

Huang L, Ramirez JC, Frampton GA et al. Anandamide exerts its antiproliferative actions on cholangiocarcinoma by activation of the GPR55 receptor. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology, 2011; 91(7), 1007–1017.

Ford LA, Roelofs AJ, Anavi-Goffer S et al. A role for L-alpha-lysophosphatidylinositol and GPR55 in the modulation of migration, orientation and polarization of human breast cancer cells. British journal of pharmacology, 2010; 160(3), 762–771.

Diaz-Arteaga A, Vazquez MJ, Vazquez-Martinez R et al. The atypical cannabinoid O-1602 stimulates food intake and adiposity in rats. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism, 2012; 14(3), 234–243.

Moreno-Navarrete JM, Catalan V, Whyte L et al. The L-alpha-lysophosphatidylinositol/GPR55 system and its potential role in human obesity. Diabetes, 2012; 61(2), 281–291.

Romero-Zerbo SY, Rafacho A, Diaz-Arteaga A et al. A role for the putative cannabinoid receptor GPR55 in the islets of Langerhans. The Journal of endocrinology, 2011; 211(2), 177–185.

Staton PC, Hatcher JP, Walker DJ et al. The putative cannabinoid receptor GPR55 plays a role in mechanical hyperalgesia associated with inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Pain, 2008; 139(1), 225–236.

Schuelert N, McDougall JJ. The abnormal cannabidiol analogue O-1602 reduces nociception in a rat model of acute arthritis via the putative cannabinoid receptor GPR55. Neuroscience letters, 2011; 500(1), 72–76.

Marco EM, Echeverry-Alzate V, Lopez-Moreno JA, Gine E, Penasco S, Viveros MP. Consequences of early life stress on the expression of endocannabinoid-related genes in the rat brain. Behav Pharmacol, 2014; 25(5–6), 547–556.

Rahimi A, Hajizadeh Moghaddam A, Roohbakhsh A. Central administration of GPR55 receptor agonist and antagonist modulates anxiety-related behaviors in rats. Fundamental & clinical pharmacology, 2015; 29(2), 185–190.

Sylantyev S JT, Ross RA, Rusakov, DA. The enigmatic receptor GPR55 potentiates neurotransmitter release at central synapses. Society for Neuroscience Conf Proc, Washington, 2011; Program 653.01, Poster B28

Jensen TP SS, Ross RA, Rusakov DA. GPR55 modulates transmitter release and short term plasticity in the hippocampus by initiating store mediated pre-synaptic Ca2+ entry. Soc for Neurosci Conf Proc, Washington, 2011; Program 448.08, Poster G4

Vermeulen J, De Preter K, Lefever S et al. Measurable impact of RNA quality on gene expression results from quantitative PCR. Nucleic acids research, 2011; 39(9), e63.

Klempan TA, Ernst C, Deleva V, Labonte B, Turecki G. Characterization of QKI gene expression, genetics, and epigenetics in suicide victims with major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry, 2009; 66(9), 824–831.

Liu QR, Pan CH, Hishimoto A et al. Species differences in cannabinoid receptor 2 (CNR2 gene): identification of novel human and rodent CB2 isoforms, differential tissue expression and regulation by cannabinoid receptor ligands. Genes Brain Behav, 2009; 8(5), 519–530.

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods (San Diego, Calif, 2001; 25(4), 402–408.

Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. The Journal of biological chemistry, 1951; 193(1), 265–275.

Trifilieff P, Rives ML, Urizar E et al. Detection of antigen interactions ex vivo by proximity ligation assay: endogenous dopamine D2-adenosine A2A receptor complexes in the striatum. BioTechniques, 2011; 51(2), 111–118.

Borroto-Escuela DO, Tarakanov AO, Fuxe K. FGFR1-5-HT1A heteroreceptor complexes: implications for understanding and treating major depression. Trends in neurosciences, 2016; 39(1), 5–15.

Fuxe K, Borroto-Escuela D, Fisone G, Agnati LF, Tanganelli S. Understanding the role of heteroreceptor complexes in the central nervous system. Current protein & peptide science, 2014; 15(7), 647.

Garcia-Gutierrez MS, Ortega-Alvaro A, Busquets-Garcia A et al. Synaptic plasticity alterations associated with memory impairment induced by deletion of CB2 cannabinoid receptors. Neuropharmacology, 2013; 73, 388–396.

Li Y, Kim J. Deletion of CB2 cannabinoid receptors reduces synaptic transmission and long-term potentiation in the mouse hippocampus. Hippocampus, 2016; 26(3), 275–281.

Devinsky O, Cilio MR, Cross H et al. Cannabidiol: pharmacology and potential therapeutic role in epilepsy and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Epilepsia, 2014; 55(6), 791–802.

Blessing EM, Steenkamp MM, Manzanares J, Marmar CR. Cannabidiol as a potential treatment for anxiety disorders. Neurotherapeutics : the journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics, 2015; 12(4), 825–836.

Campos AC, Moreira FA, Gomes FV, Del Bel EA, Guimaraes FS. Multiple mechanisms involved in the large-spectrum therapeutic potential of cannabidiol in psychiatric disorders. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 2012; 367(1607), 3364–3378.

Pertwee RG. The diverse CB1 and CB2 receptor pharmacology of three plant cannabinoids: delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and delta9-tetrahydrocannabivarin. British journal of pharmacology, 2008; 153(2), 199–215.

Jollant F, Bellivier F, Leboyer M et al. Impaired decision making in suicide attempters. Am J Psychiatry, 2005; 162(2), 304–310.

van Heeringen C, Audenaert K, Van Laere K et al. Prefrontal 5-HT2a receptor binding index, hopelessness and personality characteristics in attempted suicide. J Affect Disord, 2003; 74(2), 149–158.

Turecki G. Dissecting the suicide phenotype: the role of impulsive-aggressive behaviours. J Psychiatry Neurosci, 2005; 30(6), 398–408.

Mann JJ, Waternaux C, Haas GL, Malone KM. Toward a clinical model of suicidal behavior in psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry, 1999; 156(2), 181–189.

Soderberg O, Leuchowius KJ, Gullberg M et al. Characterizing proteins and their interactions in cells and tissues using the in situ proximity ligation assay. Methods (San Diego, Calif, 2008; 45(3), 227–232.

Sierra S, Luquin N, Rico AJ et al. Detection of cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2 within basal ganglia output neurons in macaques: changes following experimental parkinsonism. Brain structure & function, 2015; 220(5), 2721–2738.

Martinez-Pinilla E, Reyes-Resina I, Onatibia-Astibia A et al. CB1 and GPR55 receptors are co-expressed and form heteromers in rat and monkey striatum. Exp Neurol, 2014; 261, 44–52.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Innovation (RETICS16/0017/0014) and Ministry of Health (PNSD 2015IO16, FIS PI14/00438) to JM, grants 2014-SGR-1236 from Generalitat de Catalunya and 201413-30 from the Fundació La Marató de TV3 to RF, and grants from Ministry of Science and Innovation (BFU2012-37907), Fundació La Marató TV3 (grant numbers 201413330 and 201441331) to JL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

García-Gutiérrez, M.S., Navarrete, F., Navarro, G. et al. Alterations in Gene and Protein Expression of Cannabinoid CB2 and GPR55 Receptors in the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex of Suicide Victims. Neurotherapeutics 15, 796–806 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-018-0610-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-018-0610-y