Abstract

Postoperative complications and mortality rates after rectal cancer surgery are higher in elderly than in non-elderly patients. The aim of this study is to evaluate whether, like in open surgery, age and comorbidities affect postoperative outcomes limiting the benefits of a laparoscopic approach. Between April 2011 and July 2020, data of 287 patients with rectal cancer submitted to laparoscopic rectal resection from different institutions were collected in an electronic database and were categorized into two groups: < 75 years and ≥ 75 years of age. Perioperative data and short-term outcomes were compared between these groups. Risk factors for postoperative complications were determined on multivariate analysis, including age groups and previous comorbidities as variables. Seventy-seven elderly patients had both higher ASA scores (p < 0.001) and cardiovascular disease rates (p = 0.02) compared with 210 non-elderly patients. There were no significative differences between groups in terms of overall postoperative complications (p = 0.3), number of patients with complications (p = 0.2), length of stay (p = 0.2) and death during hospitalization (p = 0.9). The only independent variables correlated with postoperative morbidity were male gender (OR 2.56; 95% CI 1.53–3.68, p < 0.01) and low-medium localization of the tumor (OR 2.12; 75% CI 1.43–4.21, p < 0.01). Although older people are more frail patients, short-term postoperative outcomes in patients ≥ 75 years of age were similar to those of younger patients after laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer. Elderly patients benefit from laparoscopic rectal resection as well as non-elderly patient, despite advanced age and comorbidities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Treatment of locally advanced mid or low rectal cancer is based on neoadjuvant chemoradiation followed by total mesorectal excision (TME) [1]. However, there is no consensus about the optimum surgical management of older patients [2, 3]. Elderly people are an heterogeneous subset of patients. Indeed, while it is considered appropriate to apply the same 'standard of care' to this category of patients, the increased risk of postoperative complications and mortality must be considered in patients with coexisting comorbidities and reduced physiological reserve capacity [4]. In this regard, advanced age should not represent itself a reason for exclusion of patients from radical surgery, but rather the frailty of these patients themselves is to be considered a primary risk factor [2, 3].

Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses [5,6,7,8,9] demonstrated the safety of laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery, better functional recovery and oncological outcomes comparable to open surgery. Despite it is well known that the number of elderly patients is poorly represented in clinical trials, underestimating the 'real-life data' [10,11,12], laparoscopic colorectal surgery has significant advantages in short-term outcomes also in the elderly population [13,14,15].

However, advanced age and comorbidities increase mortality and occurrence of complications after surgery for rectal cancer [3]. In fact, the preoperative comorbidity rate, which makes the patient vulnerable to postoperative complications, is highest after age 75 [16, 17] and this value may increase in the future because of demographic increase of an aging population and the increase in life expectancy [3].

For this reason, several authors investigated whether a laparoscopic approach in colorectal cancer surgery is as safe and feasible in elderly as in relatively younger patients [18] showing a significative higher overall complication rate in the old people, just like in open surgery [3]. However, focus on laparoscopic rectal resection is limited [19, 20] and these studies are mostly single center without discriminating outcomes between colon and rectal surgery [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30], despite rectal surgery is associated with higher complication rate as well as in open surgery [21, 31,32,33]. Furthermore, most of the studies concern Eastern populations [19, 21, 23,24,25,26,27,28], characterized by lower body mass index (BMI) values and a lower preoperative comorbidity rate than Western population, as well as a limited use of neoadjuvant chemoradiation in locally advanced low rectal cancer, according to Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum Guidelines for the treatment of colorectal cancer [34]. Finally, the chronological cut-off is often 70 years, although it is now widely accepted that for the definition of elderly patient it should be of 75 years [35].

Because of the paucity of data concerning rectal cancer treatment and heterogeneous studies on the issue, the aim of this study is to assess the safety of laparoscopic approach for the treatment of rectal cancer in elderly patients and the impact of age on postoperative clinical outcomes, by comparing the characteristics and results of a retrospective analysis with those of a relatively younger patient group. Additionally, the study aim to evaluate age and comorbidities as potential independent risk factor for postoperative complications.

Materials and methods

Study design

This is a retrospective multi-institutional study. Between April 2011 and July 2020, patients scheduled for rectal cancer surgery were evaluated in three centers (Federico II University Hospital—Minimally Invasive General and Oncological Surgery Unit, Monaldi Hospital in Naples, along with Colorectal Surgery Unit of Campus Biomedico University in Rome) all considered centers with high specific case volume and with consolidated experience in the minimally invasive approach. Data from prospectively maintained electronic databases were retrieved into a comprehensive dataset.

All patients submitted to surgery with laparoscopic approach were divided into two cohorts: elderly patients (age ≥ 75 years) and non-elderly patients (age < 75 years). This cut-off was used in this study since age ≥ 75 years is considered a significant risk factor for postoperative complications in colorectal surgery [25, 36, 37], being also in accordance with a recent redefinition of age limits for elderly patients [38].

The primary endpoint of the study was overall rate of postoperative complications in the two groups and to investigate whether age is in itself a risk factor related to postoperative morbidity after laparoscopic anterior resection of rectal cancer. Secondary endpoints were the detection of any other difference between the two groups regarding short-term postoperative outcomes and the identification of predictors of complications.

This study was conducted according to the STROBE Guidelines [39].

Patient selection and data collection

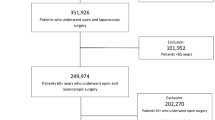

Consecutive unselected patients with primary rectal cancer submitted to elective laparoscopic anterior resection were enrolled in the study. Patients undergoing the same surgical procedure with open, robotic or transanal approach and those undergoing abdominal perineal resection or local excision by transanal endoscopy microsurgery (TEM) or transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) were excluded. Furthermore, other exclusion criteria was synchronous neoplasia (Fig. 1).

Preoperative data regarding demographic and disease characteristics were extracted from the databases. Age, gender, BMI, associated comorbidities and previous surgeries or neoadjuvant treatment, were recorded as well as the American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) score divided into two categories (ASA I-II and ASA III-IV). Tumor location was classified as high, medium and low when the distance from its lower edge to anal verge was between 10.1–15 cm, 5.1–10 cm and 0–5 cm respectively [40] while staging followed the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)/TNM system (8th edition) [41].

Postoperative complications have been reported during the postoperative hospital stay and within 30 days of surgery, including the anastomotic leakage (AL) rate with related treatments and the length of hospitalization. AL was defined as a defect of the intestinal wall at the anastomotic site evaluated by CT scan or endoscopy. Finally, a univariate and multivariate analysis of demographic, clinical and perioperative factors was performed to identify the independent variables related to postoperative complications. In particular, the analysis was conducted with patients’ stratification into groups based on age and the presence of associated comorbidities.

Surgical procedure

All patients underwent laparoscopic surgery under general anaesthesia and preoperative chemoradiotherapy in case of locally advanced tumors (T3—T4 and/or N +) of the middle/lower rectum. Anterior resection with partial mesorectal excision (PME) was performed for tumors of the upper rectum. When the neoplasm involved the middle and lower third of the rectum, a total mesorectal excision (TME) was performed according to international guidelines [1, 42] with a temporary protective loop ileostomy. A mechanical anastomosis was performed by double stapling technique or alternatively a manual coloanal anastomosis and the specimen was extracted through a suprapubic incision. Conversion was defined as the need to perform a conventional laparotomy to perform the procedure or a premature abdominal incision for dissection or vascular control. All procedures were performed by surgeons experienced in colorectal surgery.

Statistical analysis

The descriptive statistics used included determination of mean values and standard deviation (SD) or median values and interquartile range (IQR) of the continuous variables, and of percentages and proportions of the categorical variables.

Statistical analysis was performed using Chi-square, Fisher’s exact test, Student’s t test test and ANOVA, where appropriate.

Binary logistic regression was used to examine the relationship between the presence of postoperative complications as a dependent variable and the possible predictors as independent variables. The following variables were included in the univariable analysis: male gender (vs. female), age at surgery (< 75 vs. ≥ 75 and < 64 vs. 65–74 vs. 75–84 vs. > 85), ASA status (ASA1-2 vs. 3–4), comorbidities (diabetes yes/no, COP yes/no, hypertension or cardiovascular diseases yes/no), previous surgery (yes vs not), smoking habits (yes/no), BMI (< 24,9 vs. 25–29,9 vs. > 30), tumor location (mid-low vs high), T stage (T1 vs. T2 vs. T3 vs. T4), neoadjuvant chemoradiation (yes/no), type of surgery (PME vs. TME), conversion to open surgery (yes/no). The multivariable analysis was performed using the stepwise backward method (Wald) and it included all the variables with a p < 0.1 at univariable analysis. The coefficients obtained from the logistic regression analysis were also expressed in terms of odds of event occurrence (odd ratio—OR). A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS software v.15.0, Chicago IL, United States) for Windows and StatsDirect statistical software (vers. 3.0 StatsDirect, London, UK).

Results

Demographics and intraoperative data

A total of 287 patients underwent laparoscopic anterior rectal resection in three different institutions between April 2011 and July 2020. Patients aged < 75 were 210 and patients aged ≥ 75 were 77. In the first group, the mean age was 62.04 ± 8.75 years while in the second group was 80.11 ± 3.29 years (p < 0.001) while 58.6% of patients under 75 and 62.3% among over 75 were male and, in both groups, the mean BMI was 25. The preoperative characteristics of the patients are reported in Table 1. No statistically significant differences between groups were noted for the location of the cancer, the preoperative T stage and the proportion of patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiation. The mean age and frequency of patients with hypertension and cardiovascular disease was significantly higher in the over 75 group (p = 0.02). Additionally, ASA score was significantly higher in the elderly than in the group of relatively younger patients (p < 0.001).

Intraoperative data are shown in Table 2. One hundred and forty (66.7%) and 63 (68.8%) anterior resections with TME and 70 (33.3%) and 24 (31.2%) anterior resections with PME were performed in the under 75 and over 75 groups, respectively. In both cases, no significant differences were found. A protective loop ileostomy was carried out in almost half of the cases in both groups. Furthermore, the difference between the two groups in the conversion rate to open surgery was not significant (5.7% vs 10.4%; p = 0.3).

Postoperative outcomes

Details of postoperative recovery outcomes are summarized in Table 3.

The overall postoperative complication rate was not significantly different between the two groups (44.3% vs. 51.9%; p = 0.3), as well as the rate of patients who developed at least one complication (32.4% vs. 40.2%; p = 0.2). The incidence of anastomotic leakage was, respectively, 15.2% and 6.5% in the under 75 and over 75 group (p = 0.07) and no differences were recorded in the management of this specific complication, as well as in the need for postoperative red blood cells (RBC) transfusions. During hospitalization, only two patients died both in the under 75 group (0.9%). The mean hospital stay was 7.0 (4.0) and 7.0 (2.75) days in the two groups (p = 0.2).

As shown in Table 4, the age of patients stratified into classes is not related to the risk of postoperative complications as well as previous comorbidities, BMI, neoadjuvant treatment, type of intervention and conversion to open during the procedure. The only independent predictive variables are represented by the male gender (OR 2.56; 95% CI 1.53–3.68, p < 0.01) and by the low-medium localization of the tumor (OR 2.12; 75% CI 1.43–4.21, p < 0.01).

Discussion

The rate of surgical resections for rectal cancer has significantly decreased over the years in patients ≥ 75 years of age [43]. This is partly due to higher comorbidity prevalence of patients [4], but also to the development of conservative treatment options showing remarkable results [44, 45], although there are still some controversial aspects and a limited application of these alternative treatments to current clinical practice [46, 47]. Surgery still remains the main 'cornerstone' for the treatment of rectal cancer, demonstrating a progressive implementation of minimally invasive techniques with acceptable oncological and functional outcomes [48]. In this setting, laparoscopy has proven to be safe, advantageous and an effective alternative to open surgery even in elderly patients with colorectal cancer [49], as well as for benign diseases [50]. Thus, the next step was to assess whether there was a difference in short-term outcomes after laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer between the elderly and non-elderly population. A recent meta-analysis finds a higher overall complication rate in elderly patients aged ≥ 75 years undergoing laparoscopic colorectal resections (p < 0.01) [18] likewise of the open approach [3]. However, the review includes both colonic and rectal laparoscopic resections. Since few studies exclusively considered rectal surgery or separately reported data after laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery in the elderly patients, [19, 20, 51, 52], the aim of the present study was to assess whether a more vulnerable population, consisting of older people, can benefit from a minimally invasive surgical approach for the treatment of rectal cancer in the same way as relatively younger people by evaluating age groups and individual or overall comorbidities as possible indipendent risk factor.

In this study, although older patients have both the ASA score and the prevalence of cardiovascular disease significantly higher than the non-elderly patients, the postoperative complication rates and the number of patients with complications between the over-75 group and the under-75 are comparable. Also, there were no significant differences in length of hospital stay and mortality rate.

The leakage rate after anterior rectal resection ranges from 3 to 23% [53]. In the present study, the incidence of anastomotic leakage is higher in the cohort of patients aged < 75 years, although it does not reach a statistically significant difference (15.2% vs. 6.5%; p = 0.07). This discrepancy can be attributed to various intraoperative risk factors such as long operative time, the number of stapler firings and anastomotic level that are associated with increased risk of leakage [54, 55], but which were not taken into account in the analysis. Treatment was mainly carried out by relaparoscopy given the great experience of the centers [56].

Finally, the results of multivariate regression analysis show that only male gender and low-mid rectal tumor localization are independent risk factors related to postoperative morbidity, whereas age and associated comorbidities did not have an impact on complications. These findings suggest that the laparoscopic approach for rectal cancer surgery is safe and appropriate even for patients aged ≥ 75 years, by demonstrating a rate of adverse events after surgery similar to that of patients under 75.

The results of the present study is consistent with the few previous reports that compared the safety and feasibility of laparoscopic rectal resection of the elderly with younger patients and they may be useful in clinical practice if interpreted wisely to mitigate the risk of conversion [57]. From Table 5, only one study exclusively focuses on rectal cancer surgery [19], two of them reported and compared preoperative patients’ data [19, 20] and no logistic regression analysis was performed in any study to identify predictors of complications. Therefore, only in the present case series, the age of patients divided into groups and the impact of individual and overall preoperative comorbidity were systematically excluded as possible independent risk factors of postoperative complications, assuming that laparoscopic surgery should be a valid choice for the elderly patient with rectal cancer because of an overall complication rate comparable to rate non-elderly patients, unlike open surgery [3] or as reported elsewhere [18].

It has been demnostrated that laparoscopy and robotic surgery have similar effectiveness in oncologic outcomes, but robotic surgery may have lower conversion rates compared to laparoscopy especially in patients with high BMI, lower lesions and after neodjuvant [58]. However, it also true that laparoscopic rectal cancer resection in selected and fit patients and in high-volume centers with laparoscopic expertise can achieve safe oncological outcomes and margins with sphincter-sparing dissection, even in ultralow rectal cancers and without needing of robotic surgery or transanal TME (TaTME) [59]. In this setting, robotic TaTME seems a promising apporach to improve the outcomes and feasibility of low rectal cancers resections but this technique, although recently described [60] is still considered too preliminary by some authors and can not be recommended as yet [61].

This study has several limitations. The absence of a satisfactory matching process limits the risk of bias regarding its retrospective design as well as the limited number of patients over 75, although data comes from multiple centers. In addition, the long-term oncological outcomes and data relating to the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery protocol (ERAS) are not included. Furthermore, the choice of a laparoscopic approach rather than others to performe rectal resection was at the discretion of each surgical team increasing the risk of selection bias. However, the analysis of data collected from high-volume laparoscopic colorectal surgery centers suggests that patients over 75 years old benefit of a laparoscopic approach as well as younger patients despite advanced age and previous comorbidities.

These findings may depend on the fact that the most problematic expression of population aging would not be the age ot the comorbidities, but the clinical condition of frailty, which is defined as “a state of increased vulnerability to poor resolution of homoeostasis after a stressor event, which increases the risk of adverse outcomes, as a consequence of cumulative decline in many physiological systems during a lifetime” [62]. However, it is believed that this cannot significantly compromise the results of the present study. In fact, a systematic review of the literature shows that the prevalence of frailty increases with age [63] and according to some authors the concept of fragility is closely related to comorbidity and frequently overlaps with it [64]. In addition, there is no clear consensus on the definition to date. On the one hand, it is considered only a phenotype of fragility exclusively linked to the physical condition; on the other, it is considered more appropriate to extend its definition to include social and psychological aspects [63]. Finally, several screening methods have been developed to predict the degree of frailty in elderly patients with cancer, but none have demonstrated sufficient discriminatory power, stating that a comprehensive geriatric assessment is the most valid modality. [65]. However, a multidisciplinary holistic assessment of the elderly patient in the perioperative period remains desirable.

Conclusions

Despite higher incidence of cardiovascular disease and a higher anesthesiologic risk, short-term postoperative outcomes in patients ≥ 75 years of age are similar to those of younger patients after laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer. Advanced age and preoperative evaluated comorbidities are not related to an increased risk of postoperative morbidity, unlike open surgery. Therefore they should not represent a limitation to laparoscopic rectal resection.

References

You YN, Hardiman KM, Bafford A et al (2020) The American society of colon and rectal surgeons clinical practice guidelines for the management of rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 63:1191–1222

Montroni I, Ugolini G, Saur NM et al (2018) Personalized management of elderly patients with rectal cancer: expert recommendations of the European society of surgical oncology, European society of coloproctology, international society of geriatric oncology, and american college of surgeons commission on cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 44:1685–1702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2018.08.003

Manceau G, Karoui M, Werner A et al (2012) Comparative outcomes of rectal cancer surgery between elderly and non-elderly patients: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol 13:e525–e536. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70378-9

Rutten HJ, den Dulk M, Lemmens VE et al (2008) Controversies of total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer in elderly patients. Lancet Oncol 9:494–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70129-3

Chen K, Cao G, Chen B, Wang M et al (2017) Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer: a meta-analysis of classic randomized controlled trials and high-quality Nonrandomized Studies in the last 5 years. Int J Surg 39:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.12.123

Zheng J, Feng X, Yang Z et al (2017) The comprehensive therapeutic effects of rectal surgery are better in laparoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 8:12717–12729. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.14215

Fleshman J, Branda ME, Sargent DJ et al (2019) Disease-free survival and local recurrence for laparoscopic resection compared with open resection of stage ii to III rectal cancer: follow-up results of the ACOSOG Z6051 randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 269:589–595. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003002

Jeong SY, Park JW, Nam BH et al (2014) Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid-rectal or low-rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): survival outcomes of an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 15:767–774. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70205-0

van der Pas MH, Haglind E, Cuesta MA et al (2013) Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer (COLOR II): short-term outcomes of a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 14:210–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70016-0

Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ et al (1999) Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med 341:2061–2067. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199912303412706

Lewis JH, Kilgore ML, Goldman DP et al (2003) Participation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 21:1383–1389. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2003.08.010

Townsley CA, Selby R, Siu LL (2005) Systematic review of barriers to the recruitment of older patients with cancer onto clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 23:3112–3124. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.00.141

Li Y, Wang S, Gao S et al (2016) Laparoscopic colorectal resection versus open colorectal resection in octogenarians: a systematic review and meta-analysis of safety and efficacy. Tech Coloproctol 20(3):153–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-015-1419-x

Grailey K, Markar SR, Karthikesalingam A et al (2013) Laparoscopic versus open colorectal resection in the elderly population. Surg Endosc 27:19–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-012-2414-1

Seishima R, Okabayashi K, Hasegawa H et al (2015) Is laparoscopic colorectal surgery beneficial for elderly patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 19(4):756–765. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-015-2748-9

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL et al (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40:373–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

Lemmens VE, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Verheij CD et al (2005) Co-morbidity leads to altered treatment and worse survival of elderly patients with colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 92:615–623. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.4913

Hoshino N, Fukui Y, Hida K et al (2019) Short-term outcomes of laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer in the elderly versus non-elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis 34:377–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-019-03234-0

Akiyoshi T, Kuroyanagi H, Oya M et al (2009) Short-term outcomes of laparoscopic rectal surgery for primary rectal cancer in elderly patients: is it safe and beneficial? J Gastrointest Surg 13:1614–1618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-009-0961-0

Roscio F, Boni L, Clerici F et al (2016) Is laparoscopic surgery really effective for the treatment of colon and rectal cancer in very elderly over 80 years old? A prospective multicentric case-control assessment. Surg Endosc 30:4372–4382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-016-4755-7

Tan KY, Konishi F, Kawamura YJ et al (2010) Laparoscopic colorectal surgery in elderly patients: a case-control study of 15 years of experience. Am J Surg 201:531–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.01.024

Kvasnovsky CL, Adams K, Sideris M et al (2016) Elderly patients have more infectious complications following laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery. Colorectal Dis 18:94–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.13109

Kazama K, Aoyama T, Hayashi T et al (2017) Evaluation of short-term outcomes of laparoscopic-assisted surgery for colorectal cancer in elderly patients aged over 75 years old: a multi-institutional study (YSURG1401). BMC Surg 17:29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-017-0229-7

Tokuhara K, Nakatani K, Ueyama Y et al (2016) Short- and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer in the elderly: a prospective cohort study. Int J Surg 27:66–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.01.035

Jeong DH, Hur H, Min BS et al (2013) Safety and feasibility of a laparoscopic colorectal cancer resection in elderly patients. Ann Coloproctol 29:22–27. https://doi.org/10.3393/ac.2013.29.1.22

Kang T, Kim HO, Kim H et al (2015) Age over 80 is a possible risk factor for postoperative morbidity after a laparoscopic resection of colorectal cancer. Ann Coloproctol 31:228–234. https://doi.org/10.3393/ac.2015.31.6.228

Lim SW, Kim YJ, Kim HR (2017) Laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer in patients over 80 years of age: the morbidity outcomes. Ann Surg Treat Res 92:423–428. https://doi.org/10.4174/astr.2017.92.6.423

Otsuka K, Kimura T, Hakozaki M et al (2016) Comparative benefits of laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer in octogenarians: a case-matched comparison of short- and long-term outcomes with middle-aged patients. Surg Today 47:587–594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-016-1410-9

Fiscon V, Portale G, Frigo F et al (2010) Laparoscopic resection of colorectal cancer: matched comparison in elderly and younger patients. Tech Coloproctol 14:323–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-010-0635-7

Inoue Y, Kawamoto A, Okugawa Y et al (2015) Efficacy and safety of laparoscopic surgery in elderly patients with colorectal cancer. Mol Clin Oncol 3:897–901. https://doi.org/10.3892/mco.2015.530

Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H et al (2005) Short-term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 365:1718–1726. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66545-2

Shearer R, Gale M, Aly OE et al (2013) Have early postoperative complications from laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery improved over the past 20 years? Colorectal Dis 15:1211–1226. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.12302

Schiphorst AH, Doeksen A, Hamaker ME et al (2014) Short-term follow-up after laparoscopic versus conventional total mesorectal excision for low rectal cancer in a large teaching hospital. Int J Colorectal Dis 29:117–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-013-1768-8

Watanabe T, Itabashi M, Shimada Y et al (2015) Japanese society for cancer of the colon and rectum. Japanese society for cancer of the colon and rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2014 for treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 20:207–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-015-0801-z

Denet C, Fuks D, Cocco F et al (2017) Effects of age after laparoscopic right colectomy for cancer: are there any specific outcomes? Dig Liver Dis 49:562–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2016.12.014

Kirchhoff P, Dincler S, Buchmann P (2008) A multivariate analysis of potential risk factors for intra- and postoperative complications in 1316 elective laparoscopic colorectal procedures. Ann Surg 248:259–265. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31817bbe3a

Ondrula DP, Nelson RL, Prasad ML et al (1992) Multifactorial index of preoperative risk factors in colon resections. Dis Colon Rectum 35:117–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02050665

Ouchi Y, Rakugi H, Arai H et al (2017) Redefining the elderly as aged 75 years and older: proposal from the joint committee of japan gerontological society and the Japan geriatrics society. Geriatr Gerontol Int 17:1045–1047. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13118

Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG et al (2007) Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 4:e297. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.004029

Horvat N, Carlos Tavares Rocha C, Clemente Oliveira B et al (2019) MRI of rectal cancer: tumor staging, imaging techniques, and management. Radiographics 39:367–387. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2019180114

Jessup JM, Goldberg RM, Asare EA, et al. (2017) Colon and rectum. In: Armin MB, Greene FJ, Byrd DR, Brookland RK, Washington MK, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer

van de Velde CJ, Boelens PG, Borras JM et al (2014) EURECCA colorectal: multidisciplinary management: European consensus conference colon and rectum. Eur J Cancer 50:1.e1-1.e34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2013.06.048

Speelman AD, van Gestel YR, Rutten HJ et al (2015) Changes in gastrointestinal cancer resection rates. Br J Surg 102:1114–1122. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.9862

Rullier E, Vendrely V, Asselineau J et al (2020) Organ preservation with chemoradiotherapy plus local excision for rectal cancer: 5-year results of the GRECCAR 2 randomised trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 5:465–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30410-8

van der Valk MJM, Hilling DE, Bastiaannet E et al (2018) Long-term outcomes of clinical complete responders after neoadjuvant treatment for rectal cancer in the International watch and wait database (IWWD): an international multicentre registry study. Lancet 391:2537–2545. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31078-X

Peltrini R, Sacco M, Luglio G et al (2019) Local excision following chemoradiotherapy in T2–T3 rectal cancer: current status and critical appraisal. Updates Surg 72:29–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-019-00689-2

Peltrini R, Caruso E, Bucci L (2019) Local regrowth after “Watch and Wait” strategy: is salvage surgery enough for disease control? Int J Colorectal Dis 34:1505–1506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-019-03348-5

Peltrini R, Luglio G, Cassese G et al (2019) Oncological outcomes and quality of life after rectal cancer surgery. Open Med (Wars) 14:653–662. https://doi.org/10.1515/med-2019-0075

Fujii S, Tsukamoto M, Fukushima Y et al (2016) Systematic review of laparoscopic vs open surgery for colorectal cancer in elderly patients. World J Gastrointest Oncol 8:573–582. https://doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v8.i7.573

Luglio G, Tarquini R, Giglio MC et al (2017) Ventral mesh rectopexy versus conventional suture technique: a single-institutional experience. Aging Clin Exp Res 29(Suppl 1):S79–S82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-016-0672-9

Chautard J, Alves A, Zalinski S et al (2008) Laparoscopic colorectal surgery in elderly patients: a matched case-control study in 178 patients. J Am Coll Surg 206:255–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.06.316

Scheidbach H, Schneider C, Hügel O et al (2005) Laparoscopic surgery in the old patient: do indications and outcomes differ? Langenbecks Arch Surg 390:328–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-005-0560-9

Rahbari NN, Weitz J, Hohenberger W et al (2009) Definition and grading of anastomotic leakage following anterior resection of the rectum: a proposal by the international study group of rectal cancer. Surgery 147:339–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2009.10.012

Qu H, Liu Y, Bi DS (2015) Clinical risk factors for anastomotic leakage after laparoscopic anterior resection for rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc 29:3608–3617. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-015-4117-x

Sciuto A, Merola G, De Palma GD et al (2018) Predictive factors for anastomotic leakage after laparoscopic colorectal surgery. World J Gastroenterol 24(21):2247–2260. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i21.2247

Cuccurullo D, Pirozzi F, Sciuto A et al (2015) Relaparoscopy for management of postoperative complications following colorectal surgery: ten years experience in a single center. Surg Endosc 29(7):1795–1803. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3862-6

Giglio MC, Luglio G, Sollazzo V et al (2017) Cancer recurrence following conversion during laparoscopic colorectal resections: a meta-analysis. Aging Clin Exp Res 29(Suppl 1):S115–S120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-016-0674-7

Gavriilidis P, Wheeler J, Spinelli A et al (2020) Robotic vs laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for rectal cancers: has a paradigm change occurred? A systematic review by updated meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis 22(11):1506–1517. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.15084

Di Saverio S, Stupalkowska W, Hussein A et al (2019) Laparoscopic ultralow anterior resection with intracorporeal coloanal stapled anastomosis for low rectal cancer: is robotic surgery or transanal total mesorectal excision always needed to achieve a good oncological and sphincter-sparing dissection: a video vignette. Colorectal Dis 21(7):848–849. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.14642

Ye J, Shen H, Li F et al (2020) Robotic-assisted transanal total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: technique and results from a single institution. Tech Coloproctol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-020-02337-z

Di Saverio S, Gallo G, Davies RJ et al (2021) Robotic-assisted transanal total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: more questions than answers. Tech Coloproctol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-020-02402-7

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S et al (2013) Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 381:752–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9

Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA et al (2012) Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 60:1487–1492. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04054.x

Theou O, Rockwood MR, Mitnitski A et al (2012) Disability and co-morbidity in relation to frailty: how much do they overlap? Arch Gerontol Geriatr 55:e1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2012.03.001

Hamaker ME, Jonker JM, de Rooij SE et al (2012) Frailty screening methods for predicting outcome of a comprehensive geriatric assessment in elderly patients with cancer: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol 13:e437–e444. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70259-0

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration.

Research involving human partecipants and/or animals

This article does not contain any experimental studies with human partecipants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Each patient signed an informed consent for any surgery, other procedures and authorization to process personal data, although this was a retrospective analysis of deidentified data.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peltrini, R., Imperatore, N., Carannante, F. et al. Age and comorbidities do not affect short-term outcomes after laparoscopic rectal cancer resection in elderly patients. A multi-institutional cohort study in 287 patients. Updates Surg 73, 527–537 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-021-00990-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-021-00990-z