Abstract

Introduction

A second-generation basal insulin analogue insulin glargine 300 U/mL (Gla-300) has been marketed in France since June 2016. This real-world study was designed to assess persistence with Gla-300 and the prevalence of related hypoglycemia requiring hospitalization as compared to first-generation basal insulins, in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Methods

A retrospective study was conducted using data in the large French comprehensive national healthcare system claims databases. Patients with T2DM newly treated with insulin in 2016 and 2017 (2-year period) were included. Three basal insulins [Gla-300, glargine 100 U/mL (Gla-100; both branded and biosimilar) and insulin detemir (IDet)] were compared for (1) persistence until treatment discontinuation using adjusted Cox models and (2) hypoglycemia requiring hospitalization over the period of insulin exposure.

Results

During the 2-year study period, in France, 181,263 patients initiated basal insulin therapy (in a basal scheme or a more complex insulin scheme), of whom 74% initiated Gla-100, 14.2% initiated IDet and 11.8% initiated Gla-300. Patient characteristics varied according to the insulin regimen in terms of age, gender, social coverage, insulin scheme, and Charlson Comorbidity Index. Overall, 72% of patients were still treated with any basal insulin after 1 year (75% in basal scheme). In all insulin treatment regimens, patients were less likely to discontinue Gla-300 as compared to Gla-100 [adjusted odds ratio (OR) 0.39, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.37–0.41], with similar results when only the basal scheme was considered (adjusted OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.35–0.40). Persistence with IDet was similar to that with Gla-100. Patients treated with Gla-100 had higher crude hospitalization rates for hypoglycemia than those receiving Gla-300 (1.4 for 100 patients-years; OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.55–0.81); however, this difference was not statistically significant after adjustment for patient characteristics. Emergency Room (ER) visits were less frequent in patients treated with Gla-300 versus Gla-100 with or without adjustment for patient characteristics (p < 0.0001).

Conclusion

Real-world persistence for basal insulin therapy in patients with T2DM was significantly better in those on Gla-300 compared with those on Gla-100 and IDet. A trend to a lower frequency of hospitalization for hypoglycemia and ER visits, whatever the cause, was also observed in patients on Gla-300.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A retrospective study was conducted using data for 2016 and 2017 in the large French comprehensive national healthcare system claims databases, with the aim to assess persistence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) for insulin glargine 300 U/mL (Gla-300) and prevalence of related hospitalized hypoglycemia, as compared to glargine 100 U/mL (Gla-100) and detemir (IDet). |

During the study period, in France, 181,263 patients initiated basal insulin therapy (in a basal scheme or in a more complex insulin scheme), of whom 74% initiated Gla-100, 14.2% initiated IDet and 11.8% initiated Gla-300. Patient characteristics varied according to the insulin regimen in terms of age, gender, health insurance coverage, insulin scheme and Charlson Comorbidity Index. |

Overall, 72% of patients were still treated with any basal insulin after 1 year (75% in basal scheme). In all insulin regimens, patients were less likely to discontinue Gla-300 as compared to Gla-100 [adjusted odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.39 0.37–0.41], with similar results when only the basal scheme was considered (adjusted OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.35–0.40). Persistence with IDet was similar to that with Gla-100. |

Crude hospitalization rates for hypoglycemia were higher in patients treated with Gla-100 vs. Gla-300 (1.4 for 100 patients-years) (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.55–0.81), but this difference was not statistically significant after adjustment for patients’ characteristics. Emergency Room (ER) visits were less frequent in patients treated with Gla-300 vs. Gla-100 (adjusted p < 0.0001). |

Real-world persistence for the treatment of T2DM was significantly improved with Gla-300 as compared to Gla-100 and IDet. A lower frequency of hospitalization for hypoglycemia and ER visits, whatever the cause, was observed in patients on Gla-300. |

Introduction

Due to the progressive nature of type 2 diabetes (T2DM), initiation of treatment with insulin is a necessary step towards achieving optimal glycemic targets. It is well established that an adequate glycemic control reduces diabetes-related microvascular and macrovascular complications [1, 2]. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) mandate an early initiation of basal insulin therapy in patients with T2DM with glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) > 11% associated with hyperglycemia symptoms and/or evidence of ongoing catabolism, such as weight loss, polyuria and polydipsia [3]. The most recent French guidelines recommend insulin therapy when treatment with oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs) and non-insulin agents have failed to achieve glycemic targets [4]. However, only 25% of all patients treated for diabetes in France are receiving insulin [5]. Therapeutic inertia is observed at every step of the management of T2DM, but this delay in intensification is even worse when insulin therapy is being considered for insulin-naïve patients [6].

An additional difficulty is that patients with T2DM are often challenged when attempting to manage their antidiabetic medications, including insulin [7]. Such difficulties may result in a low level of persistence to the insulin therapy, with this persistence defined as the proportion of patients who remain on treatment for a specific time or the duration of time from initiation to discontinuation of therapy [8]. A previous French study using the same methodology as the above-mentioned study showed that among survivors, only 75% were still treated with insulin after 12 months (81.6% for patients treated with a basal scheme) [9]. In Germany, a study conducted in the primary care setting among patients with T2DM who were initiating basal insulin supported oral therapy [10] found that 2-year persistence was 65, 53 and 59% in users of glargine 100 U/mL (Gla-100), detemir (IDet) and neutral protamine hagedorn (NPH), respectively (p < 0.001). In the setting of intensified conventional therapy, persistence was higher without differences between groups: 84, 85 and 86% in those on Gla-100, IDet and NPH, respectively (p = 0.536) [10]. Several other studies have been conducted on insulin persistence, mainly in USA. Wei et al. reported a lower rate (65%) of persistence with Gla-100 or IDet within 1 year after initiation [11]. Baser et al. conducted a retrospective study using a large claims database in the USA and found that 55.9% of patients remained on Gla-100 within 1 year after treatment initiation [12].

To date, few real-world studies have been conducted on the recently marketed second-generation, long-acting insulins, such as glargine 300 U/mL (Gla-300). Gla-300 was developed to extend the duration of action achieved with first-generation basal insulin analogues [13] and reduce the risk of hypoglycemia in patients treated with insulin. Gla-300 has a flatter and more extended time-action profile compared to Gla-100, leading to a more stable and sustained glycemic control over a 24-h period [13]. Phase III clinical trials have demonstrated a lower incidence of hypoglycemia in patients with T2DM treated with Gla-300 [14] compared to those treated with Gla-100 with a basal supported oral therapy [15] or those using basal and mealtime insulin [16]. It is well known that hypoglycemia or the fear of hypoglycemia are major barriers to the initiation and optimal use of insulin [17].

The study reported here was conducted roughly 2 years after the launch of Gla-300 in France. It is one of the first studies using the large French comprehensive national healthcare system claims databases to assess persistence to this new-generation basal insulin and the frequency of hospitalizations for severe hypoglycemia among patients with T2DM in a real-life setting versus first-generation basal insulin analogues (branded or biosimilar Gla-100 combined and Idet). Of note, at the time of the study, degludec was not marketed in France.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted using prescription claims data from the SNDS (Système National de Données de Santé), a French administrative healthcare database covering 99% of the French population (66 million inhabitants, 3.5 million with diabetes). Patients who had initiated basal insulin therapy ± OAD or GLP-1 RA from January 2016 to December 2017 were included in order to document treatment persistence without discontinuation.

The SNDS is the main French prescription claims database and includes information from other systems, such as the national hospital discharge database (PMSI). It is one of the largest health databases in the world, with data on more than 1.2 billion reimbursed care entries, 500 million medical procedures and 11 million hospital stays per year. The SNDS database contains data on all reimbursed healthcare expenditure (inpatient, outpatient and cash payments) for the entire population living in France. It also includes sociodemographic, medical and administrative data on these beneficiaries (age, gender, diagnoses of long-term diseases eligible for 100% reimbursement, diagnoses reported during hospitalizations, town of residence, date of death) [18]. This study was authorized through two French legal Ethic Committees: Expertise Committee for Research, Studies and Evaluations in the field of Health (CEREES Dossier TPS 37634bis, approval on 12 April 2018) and the National Commission for Data Protection and Liberties (CNIL-France No. 918140 approval on 31 July 2020). Informed consent was not required due to the retrospective anonymized nature of this study.

Population

An algorithm was used to qualify a patient as having diabetes if and only if this patient had received at least three reimbursements for antidiabetic drugs (oral or insulin) in 2015 (at least two reimbursements if at least one large pack size was dispensed) or in 2016, or when this patient had been hospitalized at least once with a diagnostic (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision [ICD-10]) code: E10 [Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM); E11 (T2DM) or E14 (Unspecified diabetes)]. A decision algorithm described by Charbonnel et al. [19] was then used to distinguish people with T2DM from those with T1DM. This algorithm was based on the ICD-10 codes associated with long-standing condition status or with hospitalizations reported as the primary or related diagnosis, and on the prescription of insulin.

Eligible participants were aged ≥ 18 years, had a diagnosis of T2DM and had initiated a basal insulin therapy during the period 2016–2017.

Persistence

A first initiation of basal insulin (Gla-300, Gla-100 and IDet) was defined as the index date without any prescription of insulin 1 year prior to the index date. Persistence was defined as remaining on any basal insulin or on the same insulin without discontinuation from the index date to the last prescription and was reported in months. A therapy was deemed discontinued when it was interrupted for a period of 6 months.

Biosimilar Gla-100 and Gla-300 were marketed in the course of 2016; thus, the length of time during which treatment persistence was assessed was not identical for all basal insulins, but this variation was adjusted for in the survival analysis. Duration of treatment before intensification was also conducted in the basal insulin-only group ± OAD or glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA). Treatment intensification was defined as any addition of a non-basal insulin or a GLP-1 RA to the treatment regimen, if not present at the time or within 3 months of the initiation of insulin treatment.

Changes in doses were not considered in this analysis. Discontinuation of basal insulin was further investigated to ascertain if this was followed by a prescription for other types of insulins.

Persistence data, in the basal insulin-only group, were assessed using a Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. Events were censored at the end of the observation period or with death of the patient. Survival curves were compared using adjusted Cox models or the log-rank test and non-parametric tests. Adjusted variables were age, gender, diabetes history, geographical area, health insurance coverage, insulin scheme and Charlson Comorbidity Index.

Severe Hypoglycemia

Hospitalizations for severe hypoglycemia and associated diagnoses in the study population were identified with ICD-10 codes: E160 (Drug-induced hypoglycemia without coma), E161 (Other hypoglycemia), E162 (Hypoglycemia, unspecified) and T383 (Poisoning by, adverse effect of, and underdosing of insulin and OADs). In a secondary analysis, ICD-10 codes related to diabetic comas were also considered, given that these conditions in France are often the consequence of hypoglycemia: E110 (T2DM with coma) and E140 (Unspecified diabetes mellitus with coma). Several hospitalizations for hypoglycemia events could be recorded for the same patient. This analysis was completed using data on the frequency of Emergency Room (ER) visits whatever the reason and regardless of the insulin group.

Unadjusted and adjusted analysis were conducted to compare differences between insulins. Adjusted variables were age, gender, diabetes history, geographical area, health insurance coverage, insulin scheme and Charlson Comorbidity Index.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS® V9.3 software (SAS Institute; Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Patients

Over the 2-year study period (2016 and 2017), 21,306 patients started insulin therapy with Gla-300, 25,821 started with IDet and 134,095 started with Gla-100 (Table 1). Men were more frequently started on insulin therapy with Gla-300 (56.7%) and Gla-100 (54.9%) compared to IDet, whereas women were more often prescribed IDet (50.9%) (p < 0.0001.) The mean age [± standard deviation (SD)] of the patients initiating Gla-300 and IDet was 65 ± 14.3 and 67 ± 17 years, respectively. In patients aged ≥ 74 years, insulin therapy was more likely to be initiated with Gla-100 (35.9%) and IDet (36.8%) than with Gla-300 (25.7%) (p < 0.0001). Patients initiating Gla-300 had fewer comorbidities than those treated with either IDet or Glar-100.

Initiation of Basal Insulin Therapy

Overall, basal insulin treatment with Gla-300 was most frequently started in a basal scheme without a GLP-1 RA in insulin-naïve patients (60.9%) (p < 0.0001) (Table 1); Gla-100 treatment was initiated in the basal scheme with GLP-1 RA in only a few patients (7.1%), as compared to 14.2 and 13.8% in patients initiating Gla-300 and IDet, respectively. About 30% of patients initiating IDet or Gla-100 with other insulins were started on their treatment without GLP-1 RA, compared to 21.8% with Gla-300. Overall, insulin therapy was started in T2DM patients with GLP-1 RA in 11.0% of patients.

Overall, insulin treatment was initiated by general practitioners (GPs) in 72% of these patients with T2DM (75.7% of patients initiating Gla-100 vs. 62.4% of patients initiating Gla-300).

Persistence with Basal Insulin

During the analysis of insulin persistence, we identified a subset of patients with only one insulin purchase: 4350 patients of those prescribed Gla-300; 5988 patients of those prescribed IDet and 31,417 patients of those prescribed Gla-100. These patients were then excluded from the analysis since the reasons underlying this single purchase of a basal insulin were not elucidated.

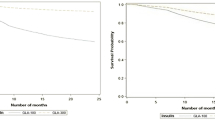

When the overall initiation of basal insulin was considered, 28% of patients discontinued purchasing the same insulin after 12 months (Fig. 1). A similar trend was observed when persistence with basal insulin therapy by patients initiating their insulin treatment in the basal insulin scheme only (without any other insulin) was considered, with 25% of patients discontinuing any basal insulin after 12 months.

When persistence was compared according to the type of basal insulin used to initiate the insulin therapy, persistence with Gla-300 was found to be significantly better than persistence with Gla-100 and IDet whatever the insulin regimens considered (Fig. 2). Gla-300 was discontinued in only 14% of patients after 12 months compared to 34% of those on Gla-100 and 37% of those on IDet (discontinuation was defined as a 6-month period without the initiated insulin). When the basal insulin-only scheme at the initiation of basal insulin theapy was considered, the discontinuation rates were 13, 33 and 32% for Gla-300, Gla-100 and IDet, respectively.

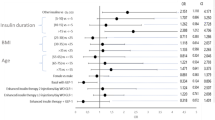

These results remain favorable to Gla-300 even after statistical adjustment for the patient’s characteristics at initiation of treatment. Persistence was better with Gla-300 than with Gla-100 when all insulin regimens were considered (probability to stop the insulin treatment over time: odds ratio (OR) 0.39, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.37–0.41] or when the basal insulin-only scheme was considered (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.35–0.40). Treatment discontinuation rates were similar between IDet and Gla-100 in all insulin regimens (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.03–1.09), and no difference was found in the group of patients treated with basal insulin only. The type of prescriber (GP or diabetologist) had no effect on these results (data not shown).

When basal insulin was discontinued, another insulin scheme was prescribed for only one-third of patients and another insulin scheme with a basal insulin (switch from a basal insulin to another) was prescribed in only 13.0% of patients (Table 2).

Treatment Intensification

A survival analysis was conducted in patients initiating their basal insulin therapy in a basal insulin-only scheme (± OAD or GLP-1 RA) up to insulin treatment intensification, as defined by the addition of any non-basal insulin or GLP-1 RA, if the patient was not receiving GLP-1 RA at the time of or within 3 months of insulin initiation. No differences were observed between the three basal insulins (Gla-300 vs. Gla-100: OR 1.04, 95% CI 0.96–1.12; IDet vs. Gla-100: OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.91–1.04).

Hypoglycemia

Overall, few episodes of hospitalized hypoglycemia were observed in this study (< 2 episodes per 100 person-years). Using crude data, hospitalized hypoglycemia events were significantly less frequent in patients treated with Gla-300 (1.4 episodes per 100 person-years) than in those treated with IDet (1.8 episodes) and Gla-100 (1.5 episodes) (Gla-300 vs. Gla-100: OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.55–0.81). However, this finding was not significant after adjusting for patient characteristics at the initiation of basal insulin therapy (Fig. 3).

Conversely, patients treated with Gla-100 were more likely to be admitted to ERs (whatever the reason) than those receiving Gla-300. The overall average number of visits per year to the ER was 0.558 (SD 2.053) with Gla-300 versus 0.873 (SD 2.652) with Gla-100 (crude OR 0.55, 95% CI 0.52–0.57; p < 0.0001). Adjusting for patient characteristics, including geographical area (see Methods), the yearly frequency of ER visits (all reasons) remained statistically significantly in favor of Gla-300 and was estimated to 0.494 visits per year with this insulin

Discussion

This retrospective study was designed to assess persistence with basal insulin therapy by patients with T2DM following treatment initiation using data from the French national insurance claims database, SNDS, that covers the entire French population. Our analysis revealed that when all insulin regimens were considered, 72% of patients continued to use basal insulin therapy after 12 months; this percentage increased to 75% of patients when only those on the basal insulin-only scheme were considered. Insulin persistence in the patients in our study is very similar to that observed in the same database in France in 2012/13 [9], but is generally better than results reported from other countries. Wei et al. reported 65% persistence with insulin glargine or IDet within the first year after initiation [11]. Baser et al. conducted a retrospective study using a large claims database in the USA and found that 55.9% of patients remained on insulin glargine within 1 year after treatment initiation [12]. Ascher-Svanum et al. conducted a study using a US Commercial Claims and Encounters database and reported that only 18% of patients continued their insulin therapy after 1 year [20]. These differences across studies could be explained by the lack of homogeneity in defining and measuring persistence with insulin therapy as well as by differences in healthcare systems.

Our results from the adjusted analyses show that persistence with Gla-300 was significantly better than that IDet and Gla-100. This result may be partly explained by a lower rate of hypoglycemic events in patients treated with Gla-300, a possibility supported by Bolli et al. who reported a lower incidence of nocturnal hypoglycemia with Gla-300 compared to Gla-100 in the EDITION 3 study [21]. A similar finding was also reported by Yki-Järvinen et al. in the EDITION 2 trial comparing the same treatments [15]. Interestingly, lower nocturnal hypoglycemia with Gla-300 was associated with a significant improvement in HbA1c [14], which can help more patients achieve an optimal glycemic control. It is well known that hypoglycemia is a major limiting factor in glycemic management in patient with diabetes. Thus, the fear of hypoglycemia should be considered when initiating a patient on insulin therapy, and treatments with a lower risk of hypoglycemia should be prescribed. Interestingly, our study did not show any differences across basal insulin treatment regimens until treatment intensification, but this approach was limited to assessing the addition of another non-basal insulin or GLP-1 RA (if the GLP-1 RA was not present at the time or within 3 months of insulin initiation) and therefore does not consider the potential for better titration of insulin.

However, several other factors may have contributed to the better persistence observed with Gla-300, including the novelty of this insulin, more frequent prescriptions of a new insulin by the specialist or some baseline characteristics not considered in the statistical adjustment conducted in the maintenance analysis.

Surprisingly, Gla-300 was less frequently initiated in patients aged ≥ 74 years, a patient population that is more susceptible to hypoglycemia. During the period of our observations, physicians had only a limited experience with Gla-300 in France in elderly patients, and the lack of evidence from clinical trials at that time may have influenced the physicians’ decision. Subsequently, however, new data from randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the safety of Gla-300 in elderly patients (≥ 75 years) [22].

Our study was not designed to determine the reasons for non-persistence with insulin therapy. However, a knowledge and understanding of these underlying reasons can prevent early discontinuation and achieve better outcomes. Factors associated with an early discontinuation of insulin therapy in a US study were younger age, female sex, comorbid conditions, visits to the ER and higher medical costs [20]. In a German study, predictors of discontinuation of basal insulin therapy were ≥ 1 documented hypoglycemia before discontinuing and diagnosed depression [23].

The crude percentage of patients hospitalized for hypoglycemia was significantly lower for those treated with Gla-300 (0.5%) than for patients treated with IDet (0.7%) or Gla-100 (0.8%). The adjusted analysis shows, however, that the trend towards a lower frequency of hypoglycemia requiring hospitalization with Gla-300 is not statistically significant. Finally, the risk of having to go to the ER (whatever the reason) during the treatment period was lower for patients treated with Gla-300 than for those treated with Gla-100 (OR 0.547, 95% CI 0.523–0.571), even after adjustment for baseline characteristics.

Our study using data from a claims database present some limitations inherent to this type of data collection. Isolated diagnosis codes reported within the database can be unreliable since diagnosis is only documented in case of hospitalizations and long-standing diseases. The database does not contain any information on clinical status, nor are the results of paraclinical examinations recorded. In addition, reasons and indications for which a specific medication was given are not documented. Nevertheless, the SNDS database is reliable and representative of all insured patients in France. Missing data are limited in the database since a prescription is required in order to initiate insulin therapy. Thus, all of the patients treated with insulin during the study period were included in the database.

Conclusion

Among patients with T2DM who initiate basal insulin therapy, early discontinuation of insulin may signal that the patients are experiencing difficulties with this therapy, possibly related to injections, side-effects or a lack of efficacy. This real-world study conducted in a very large population in France found that persistence by patients with T2DM was significantly better for Gla-300 than for Gla-100 and IDet. This difference could be partly related to a lower frequency of hospitalization for hypoglycemia and fewer ER visits by patients on Gla-300. Further work is needed to better understand the underlying reasons for such differences in persistence over time.

References

Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000;321(7258):405–12.

Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(15):1577–89.

Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2018;41(12):2669–701.

Darmon P, Bauduceau B, Bringer J, et al. Prise de position de la Société Francophone du Diabète (SFD) sur la prise en charge médicamenteuse de l’hyperglycémie du patient diabétique de type 2. Méd Malad Métabol. 2017;11:577–93.

Mandereau-Bruno L, Denis P, Fagot-Campagna A, Fosse-Edorh S. Prevalence of people pharmacologically treated for diabetes and territorial variations in France in 2012. Bull Epidemiol Hebd. 2014;30–31:493–9.

Khunti K, Millar-Jones D. Clinical inertia to insulin initiation and intensification in the UK: a focused literature review. Prim Care Diabetes. 2017;11(1):3–12.

Cramer JA. A systematic review of adherence with medications for diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1218–24.

Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health. 2018;11:44–7.

Roussel R, Charbonnel B, Behar M, Gourmelen J, Emery C, Detournay B. Persistence with insulin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes in France: an insurance claims study. Diabetes Ther. 2016;7(3):537–49.

Pscherer S, Chou E, Dippel FW, Rathmann W, Kostev K. Treatment persistence after initiating basal insulin in type 2 diabetes patients: a primary care database analysis. Primary Care Diabetes. 2015;9:377–84.

Wei W, Pan C, Xie L, Baser O. Real-world insulin treatment persistence among patients with type 2 diabetes. Endocr Pract. 2014;20(1):52–61.

Baser O, Tangirala K, Wei W, Xie L. Real-world outcomes of initiating insulin glargine-based treatment versus premixed analog insulins among US patients with type 2 diabetes failing oral antidiabetic drugs. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:497–505.

Vargas-Uricoechea H. Efficacy and safety of insulin glargine 300 U/mL versus 100 U/mL in diabetes mellitus: a comprehensive review of the literature. J Diabetes Res. 2018;2018:2052101.

Ritzel R, Roussel R, Giaccari A, Vora J, Brulle-Wohlhueter C, Yki-Jarvinen H. Better glycaemic control and less hypoglycaemia with insulin glargine 300 U/mL vs. glargine 100 U/mL: 1-year patient-level meta-analysis of the EDITION clinical studies in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:541–8.

Yki-Järvinen H, Bergenstal RM, Bolli GB, et al. Glycaemic control and hypoglycaemia with new insulin glargine 300 U/ml versus insulin glargine 100 U/ml in people with type 2 diabetes using basal insulin and oral antihyperglycaemic drugs: the EDITION 2 randomized 12-month trial including 6-month extension. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17(12):1142–9.

Riddle MC, Bolli GB, Ziemen M, et al. New insulin glargine 300 units/mL versus glargine 100 units/mL in people with type 2 diabetes using basal and mealtime insulin: glucose control and hypoglycemia in a 6-month randomized controlled trial (EDITION 1). Diabetes Care. 2014;37(10):2755–62.

Cryer PE. The barrier of hypoglycemia in diabetes. Diabetes. 2008;57(12):3169–76.

Tuppin P, de Roquefeuil L, Weill A, Ricordeau P, Merliere Y. French national health insurance information system and the permanent beneficiaries sample. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2010;58:286–90.

Charbonnel B, Simon D, Dallongeville J, et al. Direct medical costs of type 2 diabetes in France: an insurance claims database analysis. PharmacoEcon Open. 2017;2(2):209–19.

Ascher-Svanum H, Lage MJ, Perez-Nieves M, et al. Early discontinuation and restart of insulin in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Ther. 2014;5(1):225–42.

Bolli GB, Riddle MC, Bergenstal RM, et al. New insulin glargine 300 U/ml compared with glargine 100 U/ml in insulin-naïve people with type 2 diabetes on oral glucose-lowering drugs: a randomized controlled trial (EDITION 3). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17(4):386–94.

Ritzel R, Harris SB, Baron H, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing efficacy and safety of insulin glargine 300 Units/mL versus 100 Units/mL in older people with type 2 diabetes: results from the SENIOR study [published correction appears in Diabetes Care. 2019;42(8):1604]. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(8):1672–1680.

Kostev K, Dippel FW, Rathmann W. Predictors of early discontinuation of basal insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes in primary care. Prim Care Diabetes. 2016;10(2):142–7.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was funded by Sanofi France. The Rapid Service Fee was funded by CEMKA-EVAL.

Editorial Assistance

Editorial assistance was provided by Ms Maïmouna Coulibaly (freelance medical writer, Malvern, PA USA). This assistance was funded by CEMKA-EVAL which also employed two of the authors.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Ronan Roussel is an advisory panel member for Astra-Zeneca, Sanofi, MSD, Eli Lilly, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Janssen, Mundipharma, Novo Nordisk and Physiogenex; and has received research funding and provided research support to Amgen, Diabnext, Sanofi and Novo Nordisk. Clement Teissier and Bruno Detournay are employed by CEMKA, a research and consulting firm providing studies and advisory services for private and public organisms. Bruno Detournay served as an advisor, consultant, or member of a speaker bureau for Merck Sharpe & Dohme Corp., Novo Nordisk and Pfizer Inc. Sanofi-aventis. Zahra Boultif and Amar Bahloul are employees of Sanofi-Aventis. Bernard Charbonnel has received fees for consultancy, speaking, travel or accommodation from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., Novartis AG, Novo Nordisk A/S, Sanofi and Takeda Development Centre Europe Ltd. Bernard Charbonnel is also a member of the journal’s Editorial Board.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was authorized through two French legal Ethic Committees: Expertise Committee for Research, Studies and Evaluations in the field of Health (CEREES Dossier TPS 37634bis, approval on 12 April 2018) and the National Commission for Data Protection and Liberties (CNIL-France No. 918140 approval on 31 July 2020). Informed consent was not required due to the retrospective anonymized nature of this study.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to French regulation on National Health Insurance data. Access to and processing of these data is subject to an authorization by the French Data Protection Authority (the CNIL) following the opinion of a dedicated ethical and scientific committee (currently named CESREES).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Digital Features

To view digital features for this article go to: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12482432.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Roussel, R., Detournay, B., Boultif, Z. et al. Persistence with Basal Insulin and Frequency of Hypoglycemia Requiring Hospitalization in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Ther 11, 1861–1872 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-020-00874-2

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-020-00874-2