Abstract

Helicopters are frequently operating in confined areas where the complex flow fields that develop in windy conditions may result in dangerous situations. Tools to analyse the interaction between rotorcraft wakes and ground obstacles are therefore essential. This work, carried out within the activity of the GARTEUR Action Group 22 on “Forces on Obstacles in Rotor Wake”, attempts to assess numerical models for this problem. In particular, a helicopter operating in hover above a building as well as in its wake, one main rotor diameter above the ground, has been analysed. Recent tests conducted at Politecnico di Milano provide a basis for comparison with unsteady simulations performed, with and without wind. The helicopter rotor has been modelled using steady and unsteady actuator disk methods, as well as with fully resolved blade simulations. The results identify the most efficient aerodynamic model that captures the wakes interaction, so that real-time coupled simulations can be made possible. Previous studies have already proved that the wake superposition technique cannot guarantee accurate results if the helicopter is close to the obstacle. The validity of that conclusion has been further investigated in this work to determine the minimum distance between helicopter and building at which minimal wake interference occurs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Helicopters are increasingly employed in confined areas for search and rescue missions, urban transport and surveillance, offshore structure maintenance, etc. , because of their hovering capability, low speed flying and vertical take-off and landing. In these situations, the helicopter operates near the ground and/or obstacles and the complex flow fields that develop, especially in windy conditions, may result in dangerous situations, as can be seen from the accident reports of the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) [1] or the International Helicopter Safety Team (IHST) [2]. Moreover, the helicopter pilot has to deal with high workload, as well as performance issues, and handling of the vehicle. The rotor wake may also induce unsteady forces on the obstacles causing structural damage, and noise levels may increase discomfort to the people residing or working in the area.

Tools that allow the analysis of the helicopter–obstacle wake interaction are therefore essential, and the Aeronautical Research and Technology in Europe, Action Group “Forces on Obstacles in Rotor Wake” (GARTEUR AG22) aims to generate more comprehensive experimental databases and to develop a reliable and efficient numerical model of this phenomenon.

This work contributes to the GARTEUR AG22 by investigating numerically the interference between a building, simplified as a sharp parallelepiped, and a helicopter operating in its vicinity. Unsteady rotor simulations with fully resolved blades (high fidelity CFD) are first performed to validate the flow solver by means of a comparison with experimental data. Secondly, the same method was employed to evaluate the accuracy of simpler aerodynamic models. Simulations using the actuator disk (AD) and the unsteady actuator disk (UAD) models were carried out, while the actuator line technique was not considered because of its higher computational cost. An additional objective of the paper is to investigate the validity of the wake superposition technique, which is a simple method for simulating the flow field around two or more bodies, and to determine the minimum distance between them where the interaction can be considered negligible.

In the past, several studies were carried out in the direction of this paper. Quinlieven and Long [3] analysed the behaviour of the rotor operating in the wake of a large structure. Flow visualisations and a blade element vortex model with corrections for contraction and skewness of the wake and ground effect clearly show the development of a flow recirculation region behind the building and an alteration of the rotor downwash distribution that suggest the existence of mutual influence between rotorcraft and ground obstacles. Polsky and Wilkinson [4] investigated a similar configuration using monotone integrated large eddy simulation (MILES) and accounting for the atmospheric boundary layer. A hovering rotor, modeled as AD, near a hangar has been studied, analysing the effect of mesh density, different turbulence models and different inflow wind conditions. Predictions of downwash and outwash were compared with experimental data showing a good agreement when large meshes are used. Within the activity of the GARTEUR AG22, Politecnico di Milano carried out a series of experiments [5]. The experimental setup consists of a parallelepiped, of dimensions \(0.45\,\mathrm{m} \times 0.8\,\mathrm{m}\times 1.0\) m, and a helicopter model, based on the MD-500, with a scaled main rotor of radius 0.375 m. The rig allows to change the horizontal distance from the obstacle, height from the ground and roll attitude of the rotor. Different positions of the helicopter with respect to the building have been tested, all without wind [5]. Averaged pressure on the obstacle walls have been measured and PIV flow field surveys, on the building symmetry plane ahead of the front face, have been carried out. Another experimental investigation with a small-scale helicopter in ground effect has been performed by Paquet et al. [6] to develop a formulation of the aerodynamic forces in nonuniform flows. The balance measurements allowed to develop an empirical formulation of the ratio between the rotor thrust IGE and OGE which accounts for the value of the thrust coefficient. Smoke visualisations have been also carried out to measure trajectories and convection velocities of the tip vortices. Further configurations studied in the literature include the helicopter in the vicinity of a “well-shaped” object. Lusiak et al. [7], for example, analysed rotor and fuselage loading, air flow and flying qualities of the helicopter by means of RANS computations using the AD method. Configurations with simpler geometries have also been investigated using a complete model of the helicopter with a finite element model based on the Galerkin method for the blades and a panel method for the fuselage. The results clearly showed a very high asymmetry in the rotor loading and, in some cases, the presence of vortical structures similar to a vortex ring or a horseshoe vortex which can change significantly the rotor loading. A drop of the thrust and an increase of the required power of about 20% was also estimated.

All these studies already prove that the interaction with ground obstacles may considerably affect the dynamics of the helicopter leading to dangerous situations. Our knowledge of the phenomenon, however, is not complete and a deeper investigation is needed to guarantee the safety of helicopter operations. These are the reasons behind the creation of the GARTEUR AG22.

2 CFD flow solver and aerodynamic models

All calculations were performed using the parallel structured CFD solver HMB (helicopter multi-block) [8, 9].

HMB solves the dimensionless 3D Navier–Stokes equations in integral form using the arbitrary Lagrangian Eulerian (ALE) formulation for time-dependent domains with moving boundaries:

where V(t) is the time-dependent control volume, \( \partial V(t)\) its boundary, \(\mathbf {W}\) the vector of the conservative variables \(\left( \rho ,\rho u,\rho v, \rho w, \rho E\right) ^T\) and \(\mathbf {F_i}\) and \(\mathbf {F_v}\) the inviscid and viscous fluxes.

The viscous stress tensor is usually approximated in HMB using the Boussinesq hypothesis [10]. Different turbulence models have been implemented into the flow solver: one equation models of the Spalart–Allmaras family [11, 12] and two-equation models of \(k-\omega \) family [13,14,15]. Algebraic Reynolds stress models are also available.

The Navier–Stokes equations are discretised, on the multi-block grid, using a cell-centred finite volume approach. A curvilinear coordinate system is adopted to simplify the formulation of the discretised terms, since body-conforming grids are adopted. The system of equations to be solved is:

where \(\mathbf {W}_{i,j,k}\) is the vector of conserved variables in each cell, \(\mathcal{{V}}_{i,j,k}\) denotes its volume and \(\mathbf {R}_{i,j,k}\) represents the flux residual.

Osher’s upwind scheme [16] is used to resolve the convective fluxes for its robustness, accuracy and stability properties. The monotone upstream-centred schemes for conservation laws (MUSCL) variable extrapolation method [17] is employed in conjunction to formally provide second-order accuracy. The van Albada limiter [18] is also applied to remove any spurious oscillations across shock waves. The integration in time is performed with an implicit dual-time method to achieve fast convergence. The linear system is solved using a Krylov subspace algorithm, the generalised conjugate gradient method, with a block incomplete lower-upper (BILU) [19] factorisation as a pre-conditioner.

Several low Mach number schemes have been implemented in HMB to limit the loss of accuracy and round-off errors caused by the great disparity between convective and acoustic wave speeds in low-speed flows. In this work, in particular, the standard Roe scheme modified with the explicit Low Mach method developed by Rieper [20] has been used.

Boundary conditions are set by using ghost cells on the exterior of the computational domain.

To obtain an efficient parallel method based on domain decomposition, different methods are applied to the flow solver [21], and the message passing interface MPI tool is used for the communication between the processors. The load balance is calculated prior to the computation, consisting in distributing the blocks among the processors such that all processors have comparable load. Moreover, the data transfer between processors has been minimised by allowing exchange between block faces that are on the same processor. Low Mach precondition is also used to accelerate the convergence of the simulation and is decoupled between processors.

Regarding the aerodynamic methods to model the rotor, different approaches can be used in CFD. The higher-fidelity method models the blades with a full discretisation of their geometry on the computational grid. We label this approach as full blades (FB). The sliding planes technique [22] was used to allow the communication between the moving rotor grid and the fixed background. The other approach is the generalised actuator disk method [23] which represents the blades by a disk that exerts a force on the flow and acts as a momentum source/sink. The model provides useful information about dynamic inflow and turbulent wake states occurring for heavily loaded rotors, but details such as unsteady loading on the individual blades, the root and the tip blades vortices and blade boundary layer are not modeled. Therefore, the method provides a good estimate of the performance but, regarding the wake, only the two supervortices are represented. To overcome the limits of the AD model, in the actuator line technique [24] blades are represented by lines, instead of a disk, along which body forces are distributed radially. At every time step of the unsteady simulation, the local flow field and local angles of attack are computed from the movement of the blades. With tabulated airfoil data, the force per spanwise unit length is then derived using a blade-element approach. In this way, a more realistic solution of the near wake is possible, but the computational cost is significantly higher. A hybrid technique, the unsteady actuator disk, has also been developed. The aim was to represent the blade passing effect avoiding the complexity of the actuator line technique and the use of lookup tables for the aerodynamics. In this method, the load of the simpler AD model (momentum source) is applied to the disk with a “prescribed shape” which is rotating with the blades. A description of the AD and UAD model implementation as volume sources and sinks in the HMB flow solver is given below. It should be noticed that HMB is able to localise the computational cells which belong to the disk taking as input its radius, thickness, root cut-out dimension, position and attitude (tilt and roll). Therefore, to place the disk in the computational domain, a separate surface in the mesh is not needed.

2.1 Actuator disk

The implementation of the AD concept requires only the addition of source terms to the momentum and energy equations to impose the pressure jump \(\Delta P\) across the rotor disk which depends on the thrust coefficient \(C_{\rm T}\), which follows the UK convention as detailed in the nomenclature, and on the advance ratio \(\mu \). The flow field around the blades is not resolved and no computational cost is added to the Navier–Stokes equations.

If a uniform model is considered, the pressure jump in nondimensional form is:

In forward flight, the rotor load distribution is not uniform and a more realistic actuator disk model should give the pressure jump as function of the radial position on the blade r and the azimuth angle \(\Psi \). Shaidakov’s AD model [25], implemented in HMB, expresses the loading of a forward flying rotor with a distribution of the form

where the coefficients \(P_0\), \(P_{1S}\) and \( P_{2C}\) depend on rotor radius and solidity, rotor attitude, advance ratio, thrust coefficient, lift coefficient slope and freestream velocity. The model accounts for blade tip offload and rotor reverse flow region, as well as the rotor hub. Its advantage is its efficiency and the ability to provide results with no iterative methods. As an example, the load distributions for the advancing and retreating blades are shown in Fig. 1, while in Fig. 2 the downwash distribution on the rotor disk plane, for a typical forward flight condition, is compared with the uniform AD. Application examples of Shaidakov’s model can be found in [26, 27]. The model originates from the theory of an ideal lifting rotor in incompressible flow and it has been tuned for realism using test data. A brief description of the model in its first approximation is given below.

Nonuniform actuator disk [25] model in HMB (the wind is parallel to the x axis, positive in the positive axis direction, and the rotor rotates anticlockwise when viewed from above). Pressure distribution for different thrust coefficients and advance ratios. The model assumes a symmetric loading with respect to the direction perpendicular to the wind, different for the advancing and the retreating side. Please note that these are results from the complete Sheidakov model, tuned with test data, and not its approximation presented in Eqs. 6–9. a Pressure jump distribution as a function of the radial coordinate for advancing (\(\Psi = \frac{\pi}{2}rad\)) and retreating (\(\Psi = \frac{3\pi}{2}rad\)) side at \(\mu = 0.05\) and \(C_{\rm T} = 0.0124\). b Non dimensional pressure jump distribution across the disk for \(\mu = 0.05\) and \(C_{\rm T} = 0.0124\). c Non dimensional pressure jump distribution across the disk at higher \(C_{\rm T}\,(\mu = 0.05\) and \(C_{\rm T} = 0.0186)\). d Non dimensional pressure jump distribution across the disk at higher advance ratio \((\mu = 0.1\) and \(C_{\rm T} = 0.0124)\)

Actuator disk model in HMB. Vertical velocity distribution in the plane of the disk (\(\mu = 0.05\), \(C_{\rm T} = 0.022\)). a Uniform actuator disk. b Non uniform actuator disk [25]

Unsteady actuator disk model implemented in HMB, \(\mu = 0.05\), \(C_T = 0.0092\), \(\Psi _{\rm blade0} = 0^{\circ }\) . a Actuator disk showing as red points the cells contained in the blade. b Vertical velocity distribution in the plane of the disk. c Wake vortical structures visualisation: isosurfaces of Q [28] coloured with the vertical velocity component

In an incompressible flow, the pressure jump of an ideal rotor disk can be written as

where \(\delta \) is the angle of the vortex cylinder slope, \((\alpha _\infty - \alpha )\) is the actual incidence of the rotor inflow and \(\gamma \) is the distribution of the circulation on disk, which is decomposed in an average component \(\gamma _0\) and a part dependent on the azimuth angle \(\gamma _\Psi \), i.e. \(\gamma = \gamma _0 + \gamma _\Psi \). The average blade loading distribution is written as

while the azimuthal component of the circulation has the form

where \(\mu _i\) is the rotor advance ratio computed using both freestream and induced velocities: \(\mu _i = (V_\infty + \overline{V_\mathrm{IND}})/V_\text {TIP}\). The average induced velocity is estimated as follows:

where the angle \(\delta ^\star \) is defined as \(\delta ^\star = \left( \frac{\pi }{4} - \frac{|\delta |}{2} \right) \). The coefficients of the model \(k_1\) and \(k_2\) have been calibrated using test data to give realistic results. As a first approximation they are determined by:

where a is the lift coefficient slope and \(\sigma \) is the rotor solidity.

2.2 Unsteady actuator disk

To introduce the rotational effect of the blades and describe in more detail the rotor wake, the UAD model has been implemented in HMB. A Gaussian function \(\eta \) is used to shape the rotor load on the computational cells that belongs to the fictitious blade.

The source term f in the momentum equation in this case is therefore in the form

where N is the number of cells belonging to the actuator disk, \(A_i\) the cell area and \(\Delta P\) the pressure jump of the actuator disk from the momentum theory. The solidity \(\sigma \) of the fictitious rotor is determined assuming that the planform of the blades is triangular until half of the rotor radius, to avoid root problems, and rectangular afterwards. The contribution of the Gaussian distribution \(\eta \) of each blade to the considered cell of the AD is defined as

where \(N_b\) is the number of blades, \(\epsilon \) is the blade’s mean aerodynamic chord and \(|s_j|\) is the arc between the cell centre and the actuator line. To guarantee that the total thrust is the same of the corresponding steady AD, the factor |A| is used to normalise the source term at each time step:

Thus, the cell distribution on the grid does not influence the global effect of the rotor disk. Weighting in this way the effect of each point of the actuator disk, the presence of the blades is accounted for. Figure 3 presents an example of the disk loading and the downwash distribution, as well as a visualisation of the wake via isosurface of the Q criterion [28]. It can be seen that the UAD model is able to represent the individual blades vortices.

3 Investigation of the interaction helicopter–obstacle

3.1 Test cases

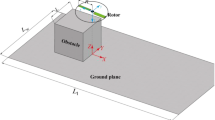

The rotor conditions and the dimensions of helicopter and building considered in this work match those of the wind tunnel experiments in [5]. The helicopter main rotor consists of four rectangular, untwisted and untapered blades with a radius \(R = 375\) mm. Blade sections use NACA 0012 airfoils with a chord \(c = 32\) mm and a collective pitch fixed to \(10^{\circ }\). A blade root cut-out equal to the 15% of the radius has been assumed and a simplified geometry of the hub has been reproduced. The angular velocity was equal to 2480 RPM, which corresponds to \(M_{\rm TIP} = 0.286\) and \(Re_{\rm TIP} = 214{,}000\). The rotor disk was always kept parallel to the incoming flow and no flapping motion was allowed. Finally, the tail rotor, as for the wind tunnel model, is not represented. Thus, the helicopter is not expected to be trimmed, but the same fixed conditions of the wind tunnel tests were reproduced. The considered obstacle, which represents a standard building, is a simple parallelepiped with sharp edges and dimensions of 800 mm in the wind direction, 1000 mm in the transversal direction and height of 450 mm. The dimensions of the obstacle are thus comparable with the rotor diameter. The adopted reference system has the xz plane aligned with the mid-span plane of the building model and the xy plane aligned with the floor; the origin of the axis is located on the floor at the mid-span of the building front face (see Fig. 4d).

Computational grid details. Dimensions, in terms of number of cells and CPUs, are reported in Tables 2 and 3. a Full computational domain with boundary conditions applied to the problem. b Structure of the assembled grid for the coupled simulations with the rotor modeled as AD or UAD (grid G2). View of the full computational domain. c Structure of the assembled grids of the coupled problem with FB (grid G1). Detail of the building and the rotor area. d Structure of the assembled grids of the coupled problem with FB (grid G1). Detail of the building and the rotor. e Detail of the rotor mesh (grid G-d)

Two relative positions between the helicopter and the obstacle have been analysed in the first part of this study. In both of them, the rotor centre is on the symmetry plane of the building at one diameter above the ground, corresponding to a distance of 0.8R from the building roof. In the first configuration, the rotor disk is completely over the building, with the rotor centre laying near the building roof centre (\(\mathbf {X_R} = {\{-R,0.0,2R\}}\)); in the second configuration, only half of the rotor disk is over the building, with the rotor centre laying exactly on the building edge (\(\mathbf {X_R} = {\{0.0,0.0,2R\}}\)).

To validate the flow solver, FB simulations in hover without wind were first performed (test cases FBh1 and FBh2; see Table 1). The presence of external wind was also considered to better investigate the phenomenon of the wake interaction between helicopter and ground obstacles using also the AD and UAD models in addition to the FB (test cases FBff2, ADff2 and UADff2; see Table 1). An advance ratio equal to \(\mu = 0.05\) was chosen for these computations in anticipation of future experiments. For a typical helicopter with an \(M_\mathrm{TIP} = 0.6\), this corresponds to a wind velocity around \(V_\infty = 10.21\) m/s, a wind speed that occurs for example on average once every 5 days in Liverpool, UK [29]. Since the \(M_\mathrm{TIP}\) and \(Re_\mathrm{TIP}\) of [5] were used, the freestream Mach and Reynolds numbers were set to \(M_\infty = 0.0143\) and \(Re_{\rm ref} = 334375\), respectively. A second condition, more typical of an offshore scenario (\(\mu = 0.15\), corresponding to \(M_\infty = 0.0429\) and \(Re_{\rm ref} = 1{,}003{,}125\)), was also studied but results are not reported here for brevity. All the numerical test cases are summarised in Table 1.

Because of the computational cost, it was decided to perform only RANS and URANS computations, using the k-\(\omega \) [13] turbulence model to close the equations. Preliminary investigations about the isolated building using different turbulence models show that the k-\(\omega \) captures the main characteristics of the flow field with the accuracy requested to study the wakes interaction in the coupled problem. All unsteady simulations were performed with a resolution of 1\(^\circ \); thus 360 steps were resolved for every main rotor revolution.

3.2 Computational grids

The computational domain is a simple parallelepiped and the final simulations correspond to the test in [5]. In this way, no side boundaries effects are expected and the rotor and building wakes can develop completely. The boundary conditions are set as follows (see Fig. 4a): on the roof and the lateral walls of the wind tunnel, as well as on the inflow and the outflow surfaces, farfield conditions can be applied because of the distance of the building and the rotor with respect to the boundaries; for the floor, a z-symmetry plane boundary condition has been chosen. A nonslip wall condition would require a fine grid resolution near the ground to resolve accurately the boundary layer structure. This is however outside of the scope of this study which is focused on the rotor wake and interaction with a building wake and for which a slip wall condition is sufficient. For the building and the helicopter (blades, hub and, if it is present, the fuselage), a solid wall condition is selected.

All grids are structured multi-block and have been generated using the ICEM Hexa tool of ANSYS [30]. Details of each grid are reported in Fig. 4 and Tables 2 and 3. An O-grid has been used around the building, and a C–H topology has been employed to mesh the rotor blades. A more detailed description of the multi-block topology used can be found in Steijl et al. [9]. The sliding plane technique [22] has been used to allow the rotor rotation for FB cases (Fig. 4e) and to allow two different mesh densities in the external part of the domain and in the region where the wakes develop (see Fig. 4b, c). This also allowed to use the same grid, in the region of the building, for the simulations with the actuator disk and those with the blades (see Table 2) to limit the differences in the results because of the different grids. For the same reason, the mesh density around the rotor and the AD in the two grids (G-b and G-e of Table 3) was kept similar.

3.3 No wind scenario and CFD validation

The wind tunnel tests reported in [5] allow a comparison between the experimental data and the numerical results obtained with FB. In particular, the configurations analysed (cases FBh1 and FBh2; see Table 1) correspond to the test cases 5.1 and 5.2 of Gibertini et al. [5].

The flow field of the two configurations is visualised in Figs. 5 and 6 via linear integral convolution (LIC) [31]. This interactive approach consists in convoluting a background texture with a digital differential analyzer (DDA)-generated filter kernel [32]. In the LIC method, the filter kernel is tangential to each vector of the field and is curved, such that it follows streamlines, and has a varying length, allowing for a better visualisation of the smaller eddies, as shown in this study. A wake visualisation is also reported in the same figures via iso-surfaces of Q-criterium [28] and streamlines. The interaction of the rotor wakes with the building is clearly visible. In the first configuration (case FBh1), the entire rotor disk is over the obstacle and the rotor wake is deviated by the building roof on its outer sides, generating big vortices around the building. Due to the top location of the rotor and its close distance to the building roof, part of the wake experiences a blockage and is deviated in the centre of the rotor inducing a fountain effect. In the second configuration (case FBh2), the presence of the building deforms the “normal” IGE rotor wake and a recirculation region still exists around the building. However, the induced blockage is highly attenuated and the fountain effect almost vanished. The rotor loading shows a strong asymmetry; thus, the helicopter is not trimmed and an action of the pilot would be necessary to keep the helicopter in this position.

Hover simulations with fully resolved blades, case FBh1. Instantaneous flow field visualisation (10th rotor revolution, \(\Psi _{\rm blade0} = 0^{\circ }\)). a LIC [31] in the xz plane coloured with the vertical velocity component. b LIC [31] in the xy plane, just above of the building, coloured with the vertical velocity component. c 3D visualisation of the rotor wake, via isosurfaces of Q [28] (non dimensional value of 0.5), as well as the low-speed recirculation zones, via streamlines. Isosurfaces of Q and streamilines are coloured with the vertical velocity component

Hover simulations with fully resolved blades, case FBh2. Instantaneous flow field visualisation (18th rotor revolution, \(\Psi _{\rm blade0} = 0^{\circ }\)). a LIC [31] in the xz plane coloured with the vertical velocity component. b LIC [31] in the xy plane, just above of the building, coloured with the vertical velocity component. c 3D visualisation of the rotor wake, via isosurfaces of Q [28] (non dimensional value of 0.5), as well as the low-speed recirculation zones, via streamlines. Isosurfaces of Q and streamilines are coloured with the vertical velocity component

When comparing the evolution of the thrust coefficient between the two configurations, the ratio \(C_{T\_FBh1}/C_{T\_FBh2}\) is equal to 1.089 in the CFD case, while the experiment provides a ratio of 1.108. The difference between the CFD predictions and experimental data is 1.64%. The pressure coefficient \(C_{\rm p}\) on the building and the flow field characteristics behind it are compared exploiting pressure taps and PIV measurements of Gibertini et al. [5]. The pressure coefficient is nondimensionalised using the rotor-induced velocity \(V_\mathrm{IND}\) computed according to the momentum theory [23] and the thrust coefficient measured during tests. The induced velocity is derived from the OGE thrust coefficient following the UK convention:

Since the geometry of the hub was simplified, a sharp blade tip was used for meshing considerations since the present study focuses on the wake properties (see Fig. 4e) and the fuselage was not represented; it was expected that the “numerical” rotor would not have the same performance as the wind tunnel model. No attempt was made to trim the rotor to achieve the same thrust. A steady simulation of the isolated rotor in OGE was therefore first carried out to quantify the difference. In particular, only one blade, at 5R above the ground, was considered and periodic boundary conditions were applied. A Froude boundary condition was used for the far field [9]. It can be noticed that the ratio \(\frac{C_{\rm t,IGE}}{C_{\rm t,OGE}} = 1.199\) is in good agreement with the data of Fradenburgh [33], which provides a value of 1.2 of this ratio at the height \(z = 0.8R\) from the ground.

Cases FBh1 (10th rotor revolution) and FBh2 (18th rotor revolution). Pressure coefficient distribution on the building: comparison between full-blade simulations, averaged over one full rotor revolution, and experimental data (tests 5.1 and 5.2 of Gibertini et al. [5]), averaged over ten observation seconds. a Experimental data FBh1. b Numerical simulation FBh1. c Experimental data FBh2. d Numerical simulation FBh2

Cases FBh1 (10th rotor revolution) and FBh2 (18th rotor revolution). Comparison of the pressure coefficient distribution on the top face of the building. CFD averaged results and maximum variations in continuous thicker lines and bars; experimental data in thinner lines and symbols. a Case FBh1. b Case FBh2

Figure 7 shows the pressure coefficient distribution on the building, calculated using the experimental induced velocity, for the two test cases FBh1 and FBh2 (see Table 1). Both numerical results, averaged on the last complete rotor revolution simulated, and the experimental data, averaged over 10 s (i.e. around 413 rotor revolutions), are reported and show qualitatively a close pressure distribution and level, in particular on the top face, while a large difference has to be registered for the lateral faces. In Fig. 8, a more detailed comparison for the top face of the building is reported by extracting profiles of averaged wall pressure coefficient from the top face of the building as well as their amplitudes for one revolution indicated by error bars. Overall, good agreement between CFD and experiment can be seen regarding the top and the front faces of the building. In addition, a global agreement with the PIV results (see Fig. 9) can be also seen. The CFD captures the velocity distribution and the flow field structures observed during the wind tunnel tests. One should remember the significant unsteadiness of this flow. Regarding the average flow field, however, the position of the vortex core in the recirculation zone is captured quite well.

Cases FBh1 (10th rotor revolution) and FBh2 (18th rotor revolution). Flow field behind the building on the symmetry plane for hover: comparison between full-blade simulation, averaged over one full rotor revolution, and experimental data (tests 5.1 and 5.2 of Gibertini et al. [5]), averaged over ten observation seconds. a Numerical simulation. Case FBh1. b Experimental data. Case 5.1 [5]. c Numerical simulation Case FBh2. d Experimental data. Case 5.2 [5]

3.4 Head wind scenario and comparison between different aerodynamic methods

To better investigate the wakes interaction between helicopter wakes and ground obstacles, computations in the presence of wind were carried out. This set of simulations considered the rotor laying on the building edge (\(\mathbf {X_R} = {\{0.0,0.0,2R\}}\)). Fully resolved blade simulations were performed, as well as unsteady computations using the AD and UAD models. It was chosen to perform unsteady computations even for the simulation that uses the AD model, as the flow around the building, which is a bluff body, is unsteady due to large flow separations. The nonuniform version of the AD model [25] was used and the input value of \(C_{\rm T}\) was chosen to correspond to the one obtained with resolved blade simulations, to have a comparison at equal thrust (\(C_{\rm T} = 0.0124\)).

Case FBff2. averaged flow field (1 rotor revolution after 18 rotor revolutions), visualised via the linear integral convolution method [31], coloured with the vertical velocity component. a Flow field in the xz plane. b Flow field in the xy plane, just above of the building

The averaged flow field of the simulation with resolved blades (case FBff2) is shown in Fig. 10. The interaction between helicopter and building is visible also in the presence of external wind. The wake of the rotor limits the development of the recirculation region behind the building [3]. The building in turn influences the rotor loading, creating asymmetry and inducing oscillations. When the helicopter is in this position, given the characteristics of the two wakes, the higher the advance ratio, the lower is the interaction. Compared with Fig. 6, it can be noticed that the limiting streamline on the building roof is now almost at the edge of the building. Averaged results for the AD (case ADff2) and UAD (case UADff2) simulations are presented in Figs. 11 and 12, respectively. Both models show the interaction between the helicopter and building: the different topology of the recirculation zone on top and downstream the building, with respect to an isolated case, is visible, as well as the asymmetry in the rotor loading. However, differences with respect to the fully resolved blades computation are also visible, as we could expect since only the global effect of the rotor is represented in the actuator disk methods. In particular, the AD presents a symmetric solution with respect to the xz plane since only the two super-vortices are represented in the wake, and the downwash at the back of the recirculation region behind the building is significantly higher. The flow features of the recirculation region on top of the building are, as expected, not captured by the model, but regarding the flow topology on top of the building some similarities with the FBff2 results are observed. The UAD technique, which introduces partially the blades’ rotational effect, gives a more realistic representation of the flow field, showing an asymmetry of the wake downstream of the building. However, differences in the flow field on the leeward part of the building roof, with respect to the FB method, are registered. Finally, it is noted that at a distance of 1D downstream of the rear part of the building, the three cases show little differences. This justifies the use of the simplest AD model for the superposition study discussed in the next section.

Case ADff2. Averaged flow field (over the equivalent of 1 rotor revolution), visualised via the linear integral convolution method [31], coloured with the vertical velocity component. a Flow field in the xz plane. b Flow field in the xy plane, just above of the building

Case UADff2. Averaged flow field (over 1 rotor revolution and after 9 full rotor revolutions), visualised via the linear integral convolution method [31], coloured with the vertical velocity component. a Flow field in the xz plane. b Flow field in the xy plane, just above of the building

4 Wake superposition method

The superposition method simply adds the flows computed separately. It consists of simulating the helicopter by means of a simple rotor method (the actuator disk in this case) and adding the velocities from a steady or unsteady “frozen” obstacle wake. The overall solution obtained by the superposition method is therefore decoupled, as it neglects the effect that each flow field causes onto the other. As shown in this work, and already proved in Quinliven and Long [3] and Crozon et al. [34], the notion of coupling is important in the context of helicopter operations in “confined areas”. For accurate results, two-way coupled simulations including both obstacle-on-rotor and rotor-on-obstacle effects are needed. However, these simulations are computationally expensive, making their use in real-time simulators difficult. Therefore, since resolving the flow field with the superposition method is much cheaper and faster, it is interesting to know when this method can guarantee accurate results and when it cannot. The objective is to determine the minimum distance between the helicopter and the building where interference can be assumed negligible.

With this purpose, steady simulations have been computed varying the rotor distance in the building wake from 0 to 9 rotor radii away from the leeward edge. The global flow field obtained by coupled simulations has been compared to the corresponding one obtained using the superposition technique. The latter is computed combining point by point the flow field variables of the two decoupled simulations, considering that the freestream is the same in both simulations in the following way:

where \(\rho '\), \(u'\) and \(p'\) are the perturbed density, velocity and pressure, respectively. All the other variables deriving from pressure, density or velocities (for example, the vorticity) are recomputed using the new variables. The rectangular zone selected for the analysis begins around one length before the building and covers the flow field until ten building lengths downstream and it is discretised using \(75 \times 75 \times 75\) points.

Analysis of the superposition method. Rotor advance ratio \(\mu =0.1\), \(M_\infty = 0.0286\). Maps of vorticity, nondimensionalised by \(V_\infty ^2\). a Isolated building. b Isolated actuator disk. c Superposition solution, rotor center above the leeward edge of the building. d Coupled solution, rotor center above the leeward edge of the building. e Superposition solution, rotor center at 3R from the leeward edge of the building. f Coupled solution, rotor center at 3R from the leeward edge of the building. g Superposition solution, rotor center at 5R from the leeward edge of the building. h Coupled solution, rotor center at 5R from the leeward edge of the building

Analysis of the superposition method. Rotor advance ratio \(\mu =0.1\), \(M_\infty = 0.0286\). Comparison of the rotor inflow: difference in the vertical velocity component at the rotor plane between coupled simulation and correspondent superposition computation. a Rotor center above the leeward edge of the building. b Rotor center at 3R from the leeward edge of the building. c Rotor center at 5R from the leeward edge of the building

Results for a forward flying rotor at an advance ratio of 0.1 are presented in terms of vorticity magnitude, nondimensionalised by \(V_\infty ^2\), in Fig. 13. The flow field of the isolated building and of the isolated actuator disk is shown, as well as the results from the coupled simulations and the correspondent superposition calculations. Significant differences are seen until the rotor is around 5R away from the building, the distance from which the superposition method seems able to give accurate results. To better quantify if the rotor is affected by the presence of the building, the rotor inflow was compared. Figure 14 shows the difference in the vertical velocity component at the rotor plane, between coupled simulation and superposition calculation. A maximum difference in the inflow \(\Vert \Delta w\Vert _\infty \) lower than 1 m/s has been chosen as the criterion to assume negligible influence of the building on the rotor. When the rotor disk is on top of the building leeward edge, \(\Vert \Delta w\Vert _\infty = 3.23\) m/s, at a distance of 3R \(\Vert \Delta w\Vert _\infty = 2.04\) m/s, while at 5R \(\Vert \Delta w\Vert _\infty = 0.95\) m/s. Thus, for a rotor flying at \(\mu = 0.1,\) the interference with the building can be considered significant if the distance is less than 5R. Instead, at this same distance, the building seems not to be influenced by the rotor. To study how the building is affected by the presence of the rotor, an analysis of the average loads on its faces was performed, comparing the results of the coupled simulations against the case of the isolated building. In particular, Fig. 15 shows the averaged vertical force coefficient \(C_{Fz}\) on the top face as a function of the rotor distance. It can be noticed that the presence of the rotor in the vicinity of the building results in lower averaged loads with respect to the isolated case. This is due to the generation of the recirculation zone on top of the building induced by the presence of the rotor wake which blocks the flow of the incoming wind. Increasing the rotor distance the interference attenuates, and it can be considered null when the rotor is at a distance equal to or greater than 3R.

Analysis of the superposition method. Rotor advance ratio \(\mu =0.05\), \(M_\infty = 0.0143\). Maps of vorticity, nondimensionalised by \(V_\infty ^2\). a Superposition solution, rotor center at 3R from the leeward edge of the building. b Coupled solution, rotor center at 3R from the leeward edge of the building. c Superposition solution, rotor center at 5R from the leeward edge of the building. d Coupled solution, rotor center at 5R from the leeward edge of the building

Analysis of the superposition method. Rotor advance ratio \(\mu =0.2\), \(M_\infty = 0.0572\). Maps of vorticity, nondimensionalised by \(V_\infty ^2\). a Superposition solution, rotor center at 3R from the leeward edge of the building. b Coupled solution, rotor center at 3R from the leeward edge of the building. c Superposition solution, rotor center at 5R from the leeward edge of the building. d Coupled solution, rotor center at 5R from the leeward edge of the building

Analysis of the superposition method. Rotor advance ratio \(\mu =0.5\), \(M_\infty = 0.14375\). Maps of vorticity, nondimensionalised by \(V_\infty ^2\). a Superposition solution, rotor center at 3R from the leeward edge of the building. b Coupled solution, rotor center at 3R from the leeward edge of the building. c Superposition solution, rotor center at 5R from the leeward edge of the building. d Coupled solution, rotor center at 5R from the leeward edge of the building

Simulations at lower and higher advance ratios have been carried out to analyse the evolution of the distance at which the superposition method matches the coupling simulation. The simulations have been performed keeping constant the tip Mach number, i.e. considering the same rotor RPM and varying the freestream velocity. In particular, three advance ratio have been considered: \(\mu =0.05\), \(\mu =0.2\) and \(\mu =0.5\). Coupled and superimposed flow fields are presented in Figs. 16, 17 and 18, respectively. For brevity, only the cases with the rotor at distance 3 and 5 radii away from the building are reported. On the one hand, by increasing the freestream velocity, the wake of the building is more extended and the induced vortices are more developed (see Fig. 19). On the other hand, the flow velocity induced by the actuator disk remains the same. However, due to the increase of the freestream velocity, the induced flow is more tilted and the generated vortices are attenuated. While it was expected that the interaction between the rotor and the building wake is reduced faster as the freestream velocity increases, the effect of the building wake strengthens and the distance at which the superposition method matches the coupled simulation (\(\Vert \Delta w\Vert _\infty < 1\) m/s) remains the same. This result can give a practical guidance to pilots that in head wind conditions, there is a distance of approximately 5R under which the flight can be affected by the wake of the building, independently of the wind speed. Regarding the loads on the building (refer to Fig. 15), the rotor influence seems to be present until around 3R in the case of \(\mu =0.05\); at \(\mu =0.2\), the influence stops before 3R while at \(\mu =0.5\) the building is almost not influenced, even when the rotor is at on the building leeward edge. For the building, the interference with the rotor is thus shown to decrease not only with the increase of the rotor distance, but also with the increase of the rotor advance ratio, because of the different direction of development of the rotor wake. Therefore, the effect of the rotor on the building can be considered important only at low advance ratio and for a distance up to 3R. Under these conditions, other simulations should be performed to evaluate with more accuracy the distance at which the influence of the rotor vanishes.

5 Conclusions

This work, within the activity of the GARTEUR Action Group 22 - “Forces on Obstacles in Rotor Wake”, studies numerically a helicopter operating in the wake of the building, both in hover and in forward flight. Different aerodynamic methods were used to represent the rotor: unsteady simulations with fully resolved blades, actuator disk and unsteady actuator disk model were performed and the results were compared.

Experimental data from the wind tunnel at the Politecnico di Milano [5] allowed a comparison for the hover case. The agreement of the pressure coefficient distribution on the building and of the flow field behind the building is overall good and allowed the validation of the CFD flow solver HMB [8, 9].

Unsteady simulations with resolved blades allow for the visualisation of the complex flow field which results from the interaction between the two aerodynamic wakes. Both hover and forward flight results show the interaction between the two wakes. Coupled helicopter–building simulations are therefore needed to study this problem, as previous works (see [3, 34]) have also suggested. An unsteady coupled simulation with the actuator disk method shows the existence of the interaction, but is not able to capture the details of the flow field with sufficient accuracy. The rotor in the AD model is represented via its integral effect and the effect of the rotation of the blades is not taken into account. The unsteadiness of the phenomenon is not captured accurately and the resulting flow field is symmetric, since the method models only the two supervortices of the wake, but not the individual blade vortices. The unsteady actuator disk model is a hybrid technique derived from the actuator line [24] and mimics the presence of the blades by shaping the load distribution on the disk using a Gaussian function. The results of an unsteady coupled computation with the unsteady actuator disk model show better agreement with resolved blade simulations, since the effect of the blades’ rotation is partially taken into account. Although this method does not show the complete complexity of the flow field generated from the interaction between the two wakes, its computational cost is comparable with that of the AD method, and significantly cheaper than the one of fully resolved blades’ simulations. An improvement of the UAD technique can therefore become the most efficient aerodynamic model to study this phenomenon. However, when comparing the average flow field on the building roof and beyond a distance of 1D away from the building, the flow field generated by the three methods (FRB, UAD and AD) is similar. As a consequence, the cheapest method, the actuator disk, has been used to analyse the interference effect between the building and the rotor.

The superposition method, which is computationally cheaper has proven to be inaccurate in the case of close proximity between the two bodies. Simulations varying the distance between the building and the rotor showed that the interference effect of the building on the rotor can be assumed negligible when the rotor is around 5R away from it, in the range of freestream velocity of the simulations. This can give a guidance to aviators that under this distance, special attention must be paid to the modification of the flight conditions. The influence of the rotor on the building, instead, is shown to be significant for a distance up to 3R and only in the case of low advance ratio.

6 Future work

Future work will aim at (1) a more extended validation and (2) a deeper investigation of the interaction phenomena, from the point of view of both rotorcraft and structure. To better comprehend the effect of the flow on the rotor, unsteady simulations including a rotor trimming method can be performed, the results of which can be compared with a multi-body dynamic code with a “frozen” obstacle wake. To evaluate any fuselage effect, computations with a full helicopter model are planned using a ROBIN fuselage [35] properly scaled. The results of these simulations could also help in the explanation of the asymmetry registered in the experiments [5]. The predictive capabilities of the AD model, as well as the UAD which has to be improved to better represent the blade radial loading distribution, will be studied in hover cases. The trimmer can also be removed from these models to replicate the experimental conditions [5]. The obstacle loads spectra will be studied, and future AG22’s experiments will provide unsteady pressure data to compare with. The UAD results will be analysed to see if the effect of the blade passing is captured. Finally, different relative positions of the helicopter and building could be analysed (e.g. configurations with the rotor windward or in a lateral position) and the effect of their relative dimensions investigated.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Actuator disk

- CFD:

-

Computational fluid dynamics

- DDA:

-

Digital differential analyser

- FB:

-

Full blades

- GARTEUR - AG:

-

Aeronautical Research and Technology in Europe-Action Group

- HMB:

-

Helicopter multi-block CFD solver

- IGE:

-

In-ground effect

- LIC:

-

Line integral convolution

- MILES:

-

Monotone integrated large Eddy simulation

- OGE:

-

Out of ground effect

- PIV:

-

Particle image velocimetry

- POLIMI:

-

Politecnico di Milano

- RANS:

-

Reynolds averaged Navier–Stokes equations

- RPM:

-

Revolutions per minute

- UAD:

-

Unsteady actuator disk

- URANS:

-

Unsteady RANS

- \(\alpha \) :

-

Rotor disk plane pitch angle, with respect to the flight path (rad)

- \(\alpha _\infty \) :

-

Freestream velocity incidence angle, measured with respect to the horizontal plane (rad)

- \(\gamma \) :

-

Circulation on the disk surface of the nonuniform AD model (m/s)

- \(\delta \) :

-

Angle of vortex cylinder slope in the nonuniform AD model (rad)

- \(\Delta P\) :

-

Pressure jump of the AD model (Pa)

- \(\Delta P^*\) :

-

Nondimensional pressure jump in the AD model \(\Delta P^*= \frac{\Delta P}{\rho _\infty V_\infty ^2}\) (−)

- \(\epsilon \) :

-

Mean blade chord used in the UAD model (m)

- \(\eta \) :

-

Gaussian function used in the UAD model (−)

- \(\lambda \) :

-

Rotor inflow ratio (−)

- \(\mu \) :

-

Rotor advance ratio \(\mu = \frac{V_\infty }{V_{\rm TIP}}\) (−)

- \(\mu _i\) :

-

Rotor advance ratio based on freestream and average induced velocities \(\mu = \frac{V_\infty + \overline{V_\mathrm{IND}}}{V_{\rm TIP}}\) (−)

- \(\rho _\infty \) :

-

Freestream density \(\left( \frac{\text {kg}}{\text {m}^3}\right) \)

- \(\sigma \) :

-

Solidity of the rotor

- \(\Psi \) :

-

Rotor azimuth angle (rad)

- a :

-

Lift coefficient slope (−)

- A :

-

Rotor area (\(\text {m}^2\))

- |A|:

-

Area normalisation factor of the UAD model (−)

- c :

-

Blade section chord (m)

- \(C_{Fz}\) :

-

Vertical force coefficient \(C_{Fz} = \frac{F_z}{\frac{1}{2}\rho _{\infty }U_{\infty }^2 A_\mathrm {FACE}}\) (−)

- \(C_p\) :

-

Pressure coefficient \(C_p = \frac{\text {p}}{\frac{1}{2} \rho _\infty V_{\rm IND}^2 \text {A}}\) (−)

- \(C_T\) :

-

Thrust coefficient \(C_T = \frac{\text {T}}{\frac{1}{2} \rho _\infty V_{\rm TIP}^2 \text {A}}\) (−)

- \(C_{T, OGE}\) :

-

Thrust coefficient out of ground effect (−)

- f :

-

Body force in the UAD model (N)

- \(L_{x}\) :

-

Length of the building in the x direction (m)

- \(M_\infty \) :

-

Freestream Mach number (−)

- \(M_\mathrm{TIP}\) :

-

Tip blade Mach number (−)

- \(N_b\) :

-

Number of rotor blades (−)

- p :

-

Pressure (Pa)

- \(p_\infty \) :

-

Freestream (far field) pressure (Pa)

- r :

-

Nondimensional radial coordinate (−)

- R :

-

Rotor radius (m)

- \(Re_\mathrm{TIP}\) :

-

Blade tip Reynolds number \(Re_\text {TIP} = \rho \frac{V_\mathrm{TIP} \text {c} }{\mu }\) (−)

- \(Re_\text {ref}\) :

-

Reference Reynolds number \(Re_\text {ref} = \rho \frac{V_\infty \text {L}_{x}}{\mu }\) (−)

- \(V_\mathrm{IND}\) :

-

Rotor-induced velocity (\(\text {m/s}\))

- \(V_\mathrm{TIP}\) :

-

Tip blade velocity (\(\text {m/s}\))

- \(V_\infty \) :

-

Freestream velocity (\(\text {m/s}\))

- \(\mathbf {X_R}\) :

-

Rotor centre position (\(\text {m}\))

- w :

-

Vertical velocity component (\(\text {m/s}\))

References

Aviation Accident Reports - National Transportation Safety Board. http://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Pages/aviation.aspx/. Last visit: 10/04/2015

International Helicopter Safety Team. http://www.ihst.org/. Last visit: 21/04/2015

Quinliven, T.A., Long, K.R.: Rotor performance in the wake of a large structure. In: Proceedings of AHS International 65th Annual Forum, vol 3, pp. 1878–1906 (2009)

Polsky, S.A., Wilkinson, C.H.: A computational study of outwash for a helicopter operating near a vertical face with comparison to experimental data. In: AIAA Modeling and Simulation Technologies Conference 10–13 August 2009, Chicago, Illinois, AIAA 2009–5684 (2009). doi:10.2514/6.2009-5684

Gibertini, G., Grassi, D., Parolini, C., Zagaglia, D., Zanotti, A.: Experimental investigation on the aerodynamic interaction between a helicopter and ground obstacles. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part G J Aerospace Eng 229(8):1395–1406 (2015). http://pig.sagepub.com/content/229/8/1395.full.pdf

Paquet, J.B., Bourez, J.P., Morgand, S.: Formulation of aerodynamic forces on helicopters in non uniform flow with scale model tests: ground effects. In: 3AF - 49th International Symposium of Applied Aerodynamics, Lille, France (2014). https://hal-onera.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01059055

Łusiak, T., Dziubiński, A., Szumański, K.: Interference between helicopter and its surroundings, experimental and numerical analysis. TASK Q. 13(4):379–392 (2008). http://153.19.250.1/files/quart/TQ2009/04/tq413m-g.pdf

Barakos, G., Steijl, R., Badcock, K., Brocklehurst, A.: Development of CFD capability for full helicopter engineering analysis. In: 31st European Rotorcraft Forum, vol 2005, pp. 91–1. Council of European Aerospace Soc. Florence, Italy, 2005. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11881/1246

Steijl, R., Barakos, G., Badcock, K.: A framework for CFD analysis of helicopter rotors in hover and forward flight. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 51(8):819–847 (2006). http://www.cfd4aircraft.com/Publications/cd_2006/papers/ijnmf_1.pdf

Boussinesq, J.: Théorie de l’Écoulement Tourbillonant et Tumultueux des Liquides dans des Lits Rectilignes à Grande Section, Tome I-II, 1st edn. Gaulthier-Villars, Paris (1897)

Spalart, P., Allmaras, S.R.: A one-equation turbulence model for aerodynamic flows. Rech. Aérosp. 1, 5–21 (1994)

Spalart, P.: Strategies for turbulence modelling and simulations. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 21(3), 252–263 (2000)

Wilcox, D.C.: Multiscale model for turbulent flows. AIAA J. 26(11), 1311–1320 (1988)

Menter, F.R.: Two-equation Eddy-viscosity turbulence models for engineering applications. AIAA J. 32(8), 1598–1605 (1994)

Menter, F.R., Egorov, Y.: A scale-adaptive simulation model using two-equation models. AIAA Pap. 1095, 2005 (2005). doi:10.2514/6.2005-1095

Osher, S., Chakravarthy, S.: Upwind schemes and boundary conditions with applications to Euler equations in general geometries. J. Comput. Phys. 50, 447–481 (1983)

van Leer, B.: Flux-vector splitting for the Euler equations. In: Eighth International Conference on Numerical Methods in Fluid Dynamics, volume 170 of Lecture Notes in Physics, pp. 507–512. Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg (1982)

Van Albada, G.D., Van Leer, B., Roberts, W.W., Jr.: A comparative study of computational methods in cosmic gas dynamics. In: Upwind and High-Resolution Schemes, pp. 95–103. Springer (1997). http://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1982A

Axelsson, O.: Iterative Solution Methods. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1994)

Rieper, F.: A low-mach number fix for Roe’s approximate riemann solver. J. Comput. Phys. 230, 5263–5287 (2011)

Lawson, S.J., Woodgate, M., Steijl, R., Barakos, G.N.: High performance computing for challenging problems in computational fluid dynamics. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 52, 19–29 (2012)

Steijl, R., Barakos, G.: Sliding mesh algorithm for CFD analysis of helicopter rotor-fuselage aerodynamics. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 58:527–549 (2008). http://www.cfd4aircraft.com/Publications/cd_2006/papers/IJNMF_sliding.pdf

Leishman, J.G.: Principles of Helicopter Aerodynamics. Cambridge University Press (2006). ISBN: 9780521858601

Sorensen, J.N., Shen, W.Z.: Numerical modeling of wind turbines wakes. J. Fluids Eng. 136, 2002

Shaidakov, V.I.: Helicopter design. In: Proceedings of Moscow Aviation Institute, vol. 381, pp. 36–68 (1978) [in Russian]

Crozon, C.: Coupling Flight Mechanics and CFD - Numerical Study of Helicopter Rotors in a Ship Airwake. Ph.D. thesis, University of Liverpool (2015)

Kusyumov, A.N., Mikhailov, S.A., Romanova, E.V., Garipov, A.O., Nikolaev, E.I., Barakos, G.: Simulation of flow around isolated helicopter fuselage. In: EPJ Web of Conferences, vol 45, pp. 01103. EDP Sciences (2013). doi:10.1051/epjconf/20134501103

Jeong, J., Hussain, F.: On the identification of a vortex. J. Fluid Mech. 285, 69–94 (1995)

Wind History in Liverpool. http://www.wunderground.com/history/. Last visit: 21/04/2015

ANSYS ICEM CFD. http://www.ansys.com/Products/Other+Products/ANSYS+ICEM+CFD/. Last visit: 10/04/2015

Cabral, B., Leedom, L.C.: Imaging vector fields using line integral convolution. In: 20th Annual Conference and Exhibition on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, Anaheim, CA, USA (1993)

Bresenham, J.E.: Algorithm for computer control of a digital plotter. IBM Syst. J. 4(1), 25–30 (1965). doi:10.1147/sj.41.0025

Fradenburgh, E.A.: The helicopter and the ground effect machine. J. Am. Helicopter Soc. 5(4), 24–33 (1960)

Crozon, C., Steijl, R., Barakos, G.N.: Numerical study of helicopter rotors in a ship airwake. J. Aircraft 51(6), 1813–1832 (2014). doi:10.2514/1.C032535

Chaffin, M., Berry, J.: Navier–stokes and potential theory solutions for a helicopter fuselage and comparison with experiment. NASA Technical Memorandum 4566 (1994)

Acknowledgements

The use of the data of the experiments by Gibertini et al. [5] is gratefully acknowledged. The authors also thank the computer centre ARCHIE-WeSt for the allocated computing time. This work is part of the GARTEUR-AG22 research on the wake interaction with the building.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Chirico, G., Szubert, D., Vigevano, L. et al. Numerical modelling of the aerodynamic interference between helicopter and ground obstacles. CEAS Aeronaut J 8, 589–611 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13272-017-0259-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13272-017-0259-y