Abstract

Polyamide thin-film composite (TFC) was fabricated on polysulfone (PS-20) base by interfacial polymerization of aqueous m-phenylenediamine (MPD) solution and 1,3,5-benzenetricarbonyl trichloride (TMC) in hexane organic solution. Multi-wall carbon nanotubes (MWCNT) were carboxylated by heating MWCNT powder in a mixture of HNO3 and H2SO4 (1:3 v/v) at 70 °C under constant sonication for different periods. Polyamide nanocomposites were prepared by incorporating MWCNT and the carboxylated MWCNT (MWCNT–COOH) at different concentrations (0.001–0.009 wt%). The developed composites were analyzed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy-attenuated total reflection, scanning electron microscopy, transmission electron microscopy, contact angle measurement, determination of salt rejection and water permeate flux capabilities. The surface morphological studies displayed that the amalgamation of MWCNT considerably changed the surface properties of modified membranes. The surface hydrophilicity was increased as observed in the enhancement in water flux and pure water permeance, due to the presence of hydrophilic nanotubes. Salt rejection was obtained between 94 and 99% and varied water flux values for TFC-reference membrane, pristine-MWCNT in MPD, pristine-MWCNT in TMC and MWCNT–COOH in MPD were 20.5, 38, 40 and 43 L/m2h. The water flux and salt rejection performances revealed that the MWCNT–COOH membrane was superior membrane as compared to the other prepared membranes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Desalination of wastewater or sea water to generate freshwater is acknowledged to be one of the major significant concerns in the science and conservational engineering fields. The deficiency of freshwater can be due to the quick increase in world population and environmental contamination (Al-Sheetan et al. 2015; Potts et al. 1981; Pendergast and Hoek 2011; Kang and Cao 2012; Greenlee et al. 2009). There are several categories of membranes, for instance reverse osmosis (RO), nanofiltration, ultrafiltration and microfiltration membranes. In these membrane methods, RO is the most extensively applied process for water desalination (Lee et al. 2011; Elimelech and Phillip 2011; Nataraj et al. 2006). In short, the RO membrane method is recognized as the most effective to eliminate small-sized ions in sea water. Presently, polyamide membranes are comprehensively used in the RO methods, because they provide better salt rejection and have high water permeation flux.

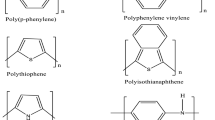

There have been several efforts to develop the performance and properties of the RO membrane, such as antifouling property, water permeability, chemical stability and salt rejection (Kang and Cao 2012; Lee et al. 2011; Li and Wang 2010; Fathizadeh et al. 2011; Zhou et al. 2009). Presently, nanocomposite polyamide membranes comprising nanomaterials such as metal oxide nanoparticles including silver, titanium, zinc, zeolite and carbon nanotube (CNT) have been established to improve the performances and properties of these membranes (Cong et al. 2007; Shawky et al. 2011; Lee et al. 2007, 2008; Lind et al. 2009; Kim et al. 2012). Among nanomaterials, carbon nanotube (CNT) that was first identified by Iijima Sumio in 1991 displays outstanding electrical, optical and mechanical properties and has been utilized in wide areas of engineering and chemistry fields. Particularly, CNT has been thoroughly studied for use in the areas of fuel cell, sensor, electrode of lithium battery, nano-probe, drug delivery, gas separation, display, energy storage, ion exchange and filters (Ajayan 1999; Nikolaev et al. 1999; Couvreur et al. 2002; Cicero et al. 2008; Gusev and Guseva 2007; Coleman et al. 2006).

CNTs have been considered for water treatment method because of their exceptional properties. The incorporation of carbon nanotube in membranes has been known to have high liquid or gas permeability and mechanical and chemical stability (Shi et al. 2013). Improved separation performances were achieved by employing those CNTs as inclusions to polymers (Qiu et al. 2009; Kim and Van der Bruggen 2010; Sahoo et al. 2010). CNTs are tubular in shape and offer the fast transport way to pass water molecules. Water molecules can go into the inside of CNT by capillary force because of the nanosized capillary structure of CNT and they can pass through the hydrophobic inner side of CNT (Iijima 1991; Hummer et al. 2001). These polymeric membranes associated CNTs having high values of water flux were attributed to the unique hydrophobic character of the CNT surfaces and uniformly aligned nanosized pores of CNT materials. There have been very few reports on the development of polymeric membranes with associated CNTs having high salt rejection and a sufficient membrane area for applied RO membrane applications.

Consequently, several polymeric membranes comprising disseminated CNTs in the support layers were established and the performances of membranes were evaluated. Nevertheless, when these membranes comprising scattered CNTs were utilized for the NaCl separation methods, many of them displayed relatively high salt rejection values. We consider that the high salt rejection values attained from these nanocomposite membranes comprising CNTs would be affected by the CNTs’ better distribution in the polymer matrix.

Nevertheless, very few studies have described carbon nanotubes employed in the RO membrane. At present, we employed multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT) in the polyamide thin film of an interfacial polymerization composite membrane for water desalination. The MWCNT–polyamide membrane might considerably produce enriched performance of RO membrane because of its quick mass transport (Falk et al. 2010). Initially, water molecules seem to move alongside the MWCNT nano channel, ensuing in an energy-saving desalination method (Zhang et al. 2011). Subsequently, current various simulations on passage of water through CNTs have recommended that not only water filled the channels and also the water passage ratio would be accelerated through that channels (Corry 2008). If the MWCNT is embedded with few hydrophilic groups such as –OH and –COOH (Zhang et al. 2011), it might develop the hydrophilicity of membranes and improve their performance.

In this study, we developed nanocomposite polyamide membrane with MWCNT through interfacial polymerizations of 1,3-diaminobenzene (MPD) and benzene-1,3,5-tricarbonyl chloride (TMC) in hexane organic solution. The developed composite membranes were characterized by TEM, SEM, FTIR-ATR and contact angle measurement, determination of water permeate flux and salt rejection capabilities. The surface morphological studies displayed that the amalgamation of MWCNT considerably improved the surface properties of the modified membranes. The surface hydrophilicity had increased water flux and pure water permeance, due to the presence of hydrophilic nanotubes. Salt rejection was obtained between 94 and 99% and the water flux for TFC-reference membrane, pristine-MWCNT in MPD, pristine-MWCNT in TMC and MWCNT–COOH in MPD was 20.5, 38, 40 and 43 L/m2h.

Experimental section

Materials

Materials and chemicals used in this study for all tests were of analytical grade as shown below: multi-walled carbon nanotubes, OD: 3–10 nm and length: 10–30 μm (KNT M31, MWCNT, Grafen Chemical Industries Company), sodium carbonate anhydrous (>99%, Scharlau, Spain), polysulfone supports (PS-20, Sepro, USA), n-hexane and m-phenylenediamine (MPD) (99%, Sigma Aldrich, USA), 1,3,5-benzenetricarbonyl trichloride (TMC) (98%, Sigma Aldrich, USA), and ultrapure deionized water (DI) (Millipore Milli-Q system, Germany).

Methods

Carboxylation of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs)

MWCNT was carboxylated by immersing MWCNT powder (0.5 g) in a mixture of H2SO4/HNO3 at 3:1, v/v (80 ml) of the acid mixture solution was placed in a 100 or 250 mL round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stirring bar and the mixture was sonicated for 30 min. The flask was then placed in an oil bath and heated to 70 °C for different periods of time as required for experimental purposes under continuous sonication. A black solid mass was attained after filtration. It was washed numerous times with distilled water and dried at 80 °C in a vacuum oven for 8 h. The resulting MWCNT mass was found to contain the –COOH group attached to the MWCNT molecule (i.e., MWCNT–COOH), which was detected using various analytical tools by Kim et al. (2014).

Modified membrane preparation

The polyamide (PA) thin-film composite (TFC) membrane was fabricated by interfacial polymerization on a PS-20 support. The PS-20 was fixed on a glass plate to prevent any probable penetration of liquid into its back from the sides. Then, it was drenched in deionized water (DI) for 1 min. At the end, the PSF support on the glass plate was eliminated to get rid of the excess water on its top surface by positioning it vertically under ambient conditions. The following polyamide TFC membranes were produced:

-

1.

The pristine-CNT disperse during the preparation of membrane was carried out by using the procedure from Kim et al. (2014).

-

2.

The TFC-reference membrane was obtained by immersing PS-20 in a 2% MPD/H2O solution for 2 min (the surplus MPD solution was removed by pressing a rubber roller). It was then immersed in 0.1% TMC/hexane solution for 1 min.

-

3.

The modified TFC membrane (MWCNT/MPD) was prepared by immersing PS-20 in a 2% MPD/H2O solution for 2 min in the presence of different amounts of MWCNT (0.001–0.009 wt%). It was then immersed in 0.1% TMC/hexane solution for 1 min.

-

4.

The modified TFC membrane (MWCNT/TMC) was obtained by immersing PS-20 in a 2% MPD/H2O solution for 2 min. It was then immersed in 0.1% TMC/hexane solution for 1 min in the presence of different amounts (0.001–0.009 wt%) of MWCNT and then rinsed with 0.2% Na2CO3, washed with DI water and finally stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C in DI water till use. The same procedure was implemented for the preparation of all the other membranes.

Characterization and instrumentation

The following instrumentation techniques were used to characterize the developed membranes.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The microstructure and surface morphology of the developed nanocomposite membrane were investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Nova NanoSEM-600, Netherlands). This was used to examine the roughness and surface morphology of the synthesized membranes.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

TEM was executed on a JEOL JEM 1101 (USA). The specimen for TEM was made by positioning the specimen on a carbon copper grid and drying out for 6–8 h at 70–80 °C in an oven.

Fourier transform infrared-attenuated total reflection (FTIR-ATR)

FTIR attached with ATR plate (Perkin Elmer, USA) was used to trace out the chemical compositions of the membrane. The surface layer of the polyamide membrane samples was placed facing the crystal surface. The FTIR-ATR spectra were estimated over a range of wave numbers from 4000 to 600 cm−1 at a resolution of 4 cm−1.

Goniometer

Contact angle study was executed using a ramé-hart Model 250 Standard Goniometer/Tensiometer with drop image (Ramé-hart Instrument Co., Succasunna, NJ, 07876 USA). A water drop was positioned on a dry uniform membrane surface and the contact angle between membrane and water drop was assessed until no more variation was noticed. The average distilled water contact angle was obtained in a sequence of eight different measurements for every membrane surface.

Cross-flow (water flux and salt rejection)

The developed membrane performance of water flux and salt rejection was examined through a cross-flow system (CF042SS316 Cell, Sterlitech Corp., USA). The membrane area in this method was 42 cm2. The temperature of the feed water was 25 °C with pH adjusted at 6–7 for 2000 ppm feed solution of NaCl and at 1 gal/min feed flow rate. The filtration was performed at the pressure of 225 psi. The salt rejection and water flux measurements were estimated after 30 min of water filtration tests to confirm stable conditions. A cross-flow filtration system schematic diagram is shown in Fig. 1.

Results and discussion

Characterization of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT)

FTIR spectroscopy

Figure 2 demonstrates the FTIR spectra of MWCNT and MWCNT–COOH. The FTIR spectrum of MWCNT displays weak sp3 C–H and sp2 C–H stretching bands at 2940 and 2850 cm−1, respectively. They are originated from the defects on MWCNT at sidewalls, which convey abundant reaction sites. The FTIR spectrum of MWCNT–COOH displays characteristic peaks of OH at 3405 cm−1, C=O at 1717 and 1580 cm−1, and –CH2 at 1208 cm−1, indicating the appearance of the carboxyl group grafted on MWCNT.

SEM analysis of carbon nanotube

The procured nanotubes were examined under scanning electron microscope (SEM) to evaluate their physical status. SEM pictures of MWCNT were taken, as displayed in Fig. 3 and revealed that the P-MWCNTs were present as bundle, surfaces were found with an average diameter of 10–20 nm and there was no amorphous carbon present in these samples, indicating lower level of defects in the production process of MWCNT and they had long length and smaller diameter.

TEM analysis

In the TEM method an electron beam is transferred through an ultrathin specimen and it interacts with the sample as it passes through it. TEM analysis of P-MWCNT were taken like SEM analysis and the TEM images are as shown in Fig. 4. It shows that MWCNTs are present as bundles. It also displays that the tube surface is smooth and clean with a diameter of 10–20 nm. MWCNTs are not amorphous and, thus, have lower level of defects and have longer length.

Characterization of PA membranes with carboxylated MWCNT (MWCNT–COOH)

FTIR-ATR spectroscopy of the modified membrane

FTIR-ATR analysis was undertaken with both thin-film composite (TFC) and TFC/MWCNT membranes were taken to evaluate the extent of interfacial polymerization with polyamides (MPD/TMC) and that with the incorporated MWCNT spectra. The pristine-MWCNT and MWCNT–COOH were termed as MWCNT-1 to MWCNT-5 [different amounts of MWCNT (0.001–0.009 wt%)] and the number increases with the increase of the acid content in the reaction mixture as shown in Fig. 5a–c.

From the above spectra, it is revealed that identical peaks are observed with both types of PA samples, i.e., TFC and TFC/MWCNT, indicating that interfacial polymerization has ensued in all of the membranes. A band at 1670 cm−1 represents the amide I band, which is representative of the C–O bands of an amide group. In addition to this, further bands are also noticed at 1550 cm−1 to indicate amide II band and NH in plane bending and at 1610 cm−1 to represent C–C ring stretching vibrations.

SEM analysis of the modified membrane

SEM analysis was conducted with TFC (Fig. 6), TFC/MWCNT in MPD at different concentrations (Fig. 7), and TFC/MWCNT–COOH in MPD at different concentrations (Fig. 8) to evaluate the surface morphologies of all these membranes. The addition of pristine-MWCNT shows that the membrane surface becomes rougher. On the other side, the insertion of MWCNT–COOH in the membranes forms the surface of polyphenylene diamine (PMD) film precisely and closely packed together. The appearance of MWCNT–COOH on the surface of the membrane indicates that some parts of the tube are not completely carboxylated, which causes decrease in salt precipitation.

Contact angle results

Contact angles of water droplets on the surfaces of different RO membranes containing different concentrations of pristine-MWCNT in TMC and in MPD as well as with MWCNT–COOH in MPD were determined and are shown in Fig. 9.

With increase of MWCNT concentration in RO membranes containing either TMC or MPD, the contact angles are found to decrease and membrane hydrophobicity also decreases. On the other hand, the contact angle drops sharply in the presence of 0.001 wt% of MWCNT–COOH in MPD. As the concentration of MWCNT–COOH increases, the contact angles slowly increase until it reaches an inflexion state. The MWCNT incorporation can also obstruct the establishment of dense cross-linked polyphenylene diamine structure, contributing to the enrichment of water flux. Nevertheless, when the quantity of MWCNT in aqueous phase is high enough (0.009 wt%), the dispersion of MWCNT becomes worse, leading to non-uniform dispersion and forming cluster and agglomeration of MWCNT in the solution. MWCNT packages have slighter particular surface area and lesser adsorption activity with membrane surface. Accordingly, with a high concentration of MWCNT in the aqueous phase, it may increase in hydrophilicity of the modified membrane and thus increase in water rate. It is observed here that our results are in agreement with those achieved by other investigators (Kim et al. 2014; Zhao et al. 2014; Amini et al. 2013).

The contact angle values of MWCNT-membranes in TMC and MPD are shown in Fig. 9, decreased by the addition of functionalized carbon nanotubes loading in the rejection layer. The outcomes of contact angle values of membranes containing functionalized MWCNT suggest that the incorporation of MWCNT–COOH has not established nano channels on the surfaces and, thus, does not allow expansion of water droplets on the surface easily (Choi et al. 2006). In addition, the COOH-functionalized MWCNT-membranes increase hydrophilicity with increased amount of MWCNTs above 0.002 wt%, at which point there is little effect on the contact angle of the modified membrane.

Permeate flux and salt rejection

Permeate flux and salt rejection ability performances were carried out with aqueous sodium chloride salt solution using three types of polyamide thin-film composites, which contained different amounts (0.001–0.009 wt%) of pristine-MWCNTs in MPD, pristine-MWCNT in TMC and MWCNT–COOH in MPD. The results are shown in Figs. 10, 11 and 12. The effect of loading MWCNT on the pure water flux and salt rejection of ensuing MWCNT-membranes (MWCNT-membranes untreated) in the state of the TFC-reference membrane (flux, 20.5 L/m2h) is shown. With the rise of MWCNTs content in the range of 0.001–0.009 wt%, the water permeation of MWCNT-membranes/MPD is improved at lower concentrations and varies at higher concentrations dramatically (flux, 38 L/m2h). Moreover, while the permeate flux was improved with slight change of salts, rejection resulted within 2%. As seen in Figs. 11 and 12, the pure water permeability nearly changed likely in the state of MWCNT/TMC (flux, 40 L/m2h) as in MWCNTs/MDP (flux, 38 L/m2h), while the salt rejection remained unchanged at all concentrations of MWCNTs. The water flux of MWCNT–COOH membranes found dramatically improved till 0.005 W% of MWCNTs (flux, 43 L/m2h) and decrease again as shown in Fig. 12, which might be due to the favorably water flow molecules through the MWCNT, while slightly change of salts rejection result within 2%. It is observed here that our outcomes are in agreement with those results acquired by other researchers. Zhang et al. (2011) found water permeability increases from 26 L/m2h with increases of MWCNTs till 71 L/m2h at 0.1% (w/v), while decrease in salt rejection from 94 to 82%. Wu et al. (2013) found the water permeability increases from 10.8 to 21.2 L/m2h at a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL and then decreases with increase of MWCNTs concentration, while salt rejection (Na2SO4) slightly changes. The MWCNT-membranes will have a prospective application in the desalination of the aqueous solution. Finally, the two membrane types have nearly the same salt rejection and different flux values.

Summary of properties of modified RO membranes of previous studies

There are several scientific reports concerning the performance of interfacially polymerized cost-effective TFC polyamide and aromatic TFC polyamide membranes on the desalination properties through membranes based on TMC and MPD. The transport properties of the prepared membranes were compared to those of the membranes reported in Table 1.

Conclusion

Three types of TFC membranes were developed containing pristine-MWCNT in TMC solution, pristine-MWCNT in MPD solution and MWCNT–COOH in MPD. All of them showed high salt rejection ability from 94 to 99%, but varied flux values were exhibited for TFC-reference membrane, pristine-MWCNT in MPD, pristine-MWCNT in TMC and MWCNT–COOH in MPD of 20.5, 38, 40 and 43 L/m2h, the highest being for MWCNT–COOH membrane, i.e., 43 L/m2h. Based on their performance capability, high salt rejection and improved flux ability were noticed with MWCNT–COOH membrane as compared to the developed membranes.

References

Ajayan P (1999) Nanotubes from carbon. Chem Rev 99:1787–1800

AL-Sheetan KM, Shaik MR, AL-Hobaib A, Alandis NM (2015) Characterization and evaluation of the improved performance of modified reverse osmosis membranes by incorporation of various organic modifiers and SnO2 nanoparticles. J Nanomater 2015:363175

Amini M, Jahanshahi M, Rahimpour A (2013) Synthesis of novel thin film nanocomposite (TFN) forward osmosis membranes using functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes. J Membr Sci 435:233–241

Choi JH, Jegal J, Kim WN (2006) Fabrication and characterization of multi-walled carbon nanotubes/polymer blend membranes. J Membr Sci 284:406–415

Cicero G, Grossman JC, Schwegler E, Gygi F, Galli G (2008) Water confined in nanotubes and between graphene sheets: a first principle study. J Am Chem Soc 130:1871–1878

Coleman JN, Khan U, Blau WJ, Gun’ko YK (2006) Small but strong: a review of the mechanical properties of carbon nanotube–polymer composites. Carbon 44:1624–1652

Cong H, Zhang J, Radosz M, Shen Y (2007) Carbon nanotube composite membranes of brominated poly (2, 6-diphenyl-1,4-phenylene oxide) for gas separation. J Membr Sci 294:178–185

Corry B (2008) Designing carbon nanotube membranes for efficient water desalination. J Phys Chem B 112:1427–1434

Couvreur P, Barratt G, Fattal E, Legrand P, Vauthier C (2002) Nanocapsule technology: a review. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carr Syst 19:99–134

Elimelech M, Phillip WA (2011) The future of seawater desalination: energy, technology, and the environment. Science 333:712–717

Falk K, Sedlmeier F, Joly L, Netz RR, Bocquet L (2010) Molecular origin of fast water transport in carbon nanotube membranes: superlubricity versus curvature dependent friction. Nano Lett 10:4067–4073

Fathizadeh M, Aroujalian A, Raisi A (2011) Effect of added NaX nano-zeolite into polyamide as a top thin layer of membrane on water flux and salt rejection in a reverse osmosis process. J Membr Sci 375:88–95

Greenlee LF, Lawler DF, Freeman BD, Marrot B, Moulin P (2009) Reverse osmosis desalination: water sources, technology, and today’s challenges. Water Res 43:2317–2348

Gusev AA, Guseva O (2007) Rapid mass transport in mixed matrix nanotube/polymer membranes. Adv Mater 19:2672–2676

Hummer G, Rasaiah JC, Noworyta JP (2001) Water conduction through the hydrophobic channel of a carbon nanotube. Nature 414:188–190

Iijima S (1991) Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature 354:56–58

Kang GD, Cao YM (2012) Development of antifouling reverse osmosis membranes for water treatment: a review. Water Res 46:584–600

Kim J, Van der Bruggen B (2010) The use of nanoparticles in polymeric and ceramic membrane structures: review of manufacturing procedures and performance improvement for water treatment. Environ Pollut 158:2335–2349

Kim E-S, Hwang G, El-Din MG, Liu Y (2012) Development of nanosilver and multi-walled carbon nanotubes thin-film nanocomposite membrane for enhanced water treatment. J Membr Sci 394:37–48

Kim HJ, Choi K, Baek Y, Kim D-G, Shim J, Yoon J, Lee J-C (2014) High-performance reverse osmosis CNT/polyamide nanocomposite membrane by controlled interfacial interactions. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 6:2819–2829

Lee SY, Kim HJ, Patel R, Im SJ, Kim JH, Min BR (2007) Silver nanoparticles immobilized on thin film composite polyamide membrane: characterization, nanofiltration, antifouling properties. Polym Adv Technol 18:562–568

Lee HS, Im SJ, Kim JH, Kim HJ, Kim JP, Min BR (2008) Polyamide thin-film nanofiltration membranes containing TiO2 nanoparticles. Desalination 219:48–56

Lee KP, Arnot TC, Mattia D (2011) A review of reverse osmosis membrane materials for desalination—development to date and future potential. J Membr Sci 370:1–22

Li D, Wang H (2010) Recent developments in reverse osmosis desalination membranes. J Mater Chem 20:4551–4566

Lind ML, Ghosh AK, Jawor A, Huang X, Hou W, Yang Y, Hoek EM (2009) Influence of zeolite crystal size on zeolite-polyamide thin film nanocomposite membranes. Langmuir 25:10139–10145

Nataraj SK, Hosamani KM, Aminabhavi TM (2006) Distillery wastewater treatment by the membrane-based nanofiltration and reverse osmosis processes. Water Res 40:2349–2356

Nikolaev P, Bronikowski MJ, Bradley RK, Rohmund F, Colbert DT, Smith K, Smalley RE (1999) Gas-phase catalytic growth of single-walled carbon nanotubes from carbon monoxide. Chem Phys Lett 313:91–97

Park J, Choi W, Kim SH, Chun BH, Bang J, Lee KB (2010) Enhancement of chlorine resistance in carbon nanotube based nanocomposite reverse osmosis membranes. Desalin Water Treat 15:198–204

Pendergast MM, Hoek EM (2011) A review of water treatment membrane nanotechnologies. Energy Environ Sci 4:1946–1971

Potts D, Ahlert R, Wang S (1981) A critical review of fouling of reverse osmosis membranes. Desalination 36:235–264

Qiu S, Wu L, Pan X, Zhang L, Chen H, Gao C (2009) Preparation and properties of functionalized carbon nanotube/PSF blend ultrafiltration membranes. J Membr Sci 342:165–172

Sahoo NG, Rana S, Cho JW, Li L, Chan SH (2010) Polymer nanocomposites based on functionalized carbon nanotubes. Prog Polym Sci 35:837–867

Shawky HA, Chae S-R, Lin S, Wiesner MR (2011) Synthesis and characterization of a carbon nanotube/polymer nanocomposite membrane for water treatment. Desalination 272:46–50

Shi Z, Zhang W, Zhang F, Liu X, Wang D, Jin J, Jiang L (2013) Ultrafast separation of emulsified oil/water mixtures by ultrathin free-standing single-walled carbon nanotube network films. Adv Mater 25:2422–2427

Wu H, Tang B, Wu P (2013) Optimization, characterization and nanofiltration properties test of MWNTs/polyester thin film nanocomposite membrane. J Membr Sci 428:425–433

Zhang L, Shi G-Z, Qiu S, Cheng L-H, Chen H-L (2011) Preparation of high-flux thin film nanocomposite reverse osmosis membranes by incorporating functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Desalin Water Treat 34:19–24

Zhao H, Qiu S, Wu L, Zhang L, Chen H, Gao C (2014) Improving the performance of polyamide reverse osmosis membrane by incorporation of modified multi-walled carbon nanotubes. J Membr Sci 450:249–256

Zhou Y, Yu S, Gao C, Feng X (2009) Surface modification of thin film composite polyamide membranes by electrostatic self deposition of polycations for improved fouling resistance. Sep Purif Technol 66:287–294

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for the financial support of this work and the facilities in its laboratories.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Hobaib, A.S., Al-Sheetan, K.M., Shaik, M.R. et al. Modification of thin-film polyamide membrane with multi-walled carbon nanotubes by interfacial polymerization. Appl Water Sci 7, 4341–4350 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-017-0578-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-017-0578-5