Abstract

Primary sternal tumors are rare and are often metastatic from neoplasms of lung, breast, thyroid, and kidney. A radical resection is indicated for their management. In recent years many rigid reconstructions are described to prevent pulmonary complications and for protection of intra -thoracic organs. It is known that chest wall is a stable yet flexible structure and hence the optimal functional outcome in spite of rigid reconstructions remains an ongoing challenge. We hypothesized that partial sternal resections does not need a rigid reconstruction and studied the functional outcome in series of five cases where simple reconstructions are done.We did standard excision of sternum and ribs depending on the site. Immediate reconstruction was done using available myocutaneous flaps (TRAM flap, Pectoralis major muscle flap and polypropylene mesh). All cases had smooth postoperative course, had excellent coverage, chest wall stability and minimal donor site morbidity. All had a short hospital stay period (8–12 days) with good functional outcome. We do hereby propose nonrigid reconstruction for partial sternal defects as a good and safe alternative.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although uncommon, primary and metastatic neoplasms occur in the chest wall. For malignant neoplasms, cure depends on completeness of resection, histological type, and tumor stage [1].About 7% of primary bone tumors localize to chest wall. Solitary metastasis to sternum is still rare. Improvement in anesthesia, intensive care, and antiseptics has improved the mortality associated [2] with chest wall resections. Absolute contraindication to sternectomy is inability to tolerate the effects from a physiologic cardiopulmonary stand point [3]. Jurkiewicz et al. in 1980 introduced the concept of muscle and myocutaneous flaps, which dramatically improved effectiveness of management of sternal dehiscence and infection [4].

Availability of chest wall reconstructive techniques has allowed for more radical excision of some large malignant chest wall tumors. The techniques to reconstruct the defects are various including the use of pedicle grafts, methyl methacrylate, metallic plates, stainless steel mesh, [5] and many others. To minimize local recurrence, wide resection is essential. Musculocutaneous flap can be used to reconstruct large sternal defects [6]. Main focus of this study was to identify the functional outcome of nonrigid reconstruction.

Materials and Methods

The indications for resections in our patients were as follows:

-

1)

Carcinoma kidney with isolated metastases to sternum

-

2)

Solitary thyroid metastases to sternum

-

3)

Soft tissue tumor infiltrating sternum and ribs

-

4)

Chondrosarcoma of sternum and ribs

-

5)

Metastasis to clavicle and sternum with unknown primary (very rare)

Every patient was subjected to thorough examination of all systems. Chest examination was done for mass site, size, mobility consistency, and invasion to underlying ribs or sternum. Scars on the chest, abdomen, and back were also noted.

For all patients, the following investigations were done:

-

1)

Chest x-ray, PA, lateral view

-

2)

CT chest to determine the depth and bone invasion, and MRI if needed

-

3)

Trucut biopsy of the mass or biopsy of the ulcer

-

4)

Metastatic work up and bone scan

-

5)

2D-ECHO, pulmonary function tests (PFT).

In case the third and fourth mild restrictive pattern was noted. In others, PFT was normal.

2D-ECHO was normal in all the cases preoperatively. 2D-ECHO was done in all the cases during follow-up period. And no PFT was repeated in any of the cases postoperatively, only bedside incentive spirometry was done, as none of our patients did have any problem related to breathing either symptomatically or on clinical assessment.

Surgical Technique

For all patients, wide excision and safety margin of 2–3 cm including affected ribs, sternum, and clavicle was done. Chest wall defect stabilization was done with vascularized pedicled muscle/myocutaneous flaps (rectus abdominus or pectoralis major muscle) and mesh repairs. Blood transfusions averaged 2 units. Average number of ICU stay was 9 days. Complications occurred were nil and there was no mortality. The central defects were reconstructed by transposing bilateral pectoralis major muscle flap in two cases. Another central and lateral defect was reconstructed by vertical rectus abdominus flap. One anterolateral defect was reconstructed with transposed pectoralis major muscle flap. Intercostal tubes and suction tubes were kept according to the flap used. Mean operating time was 2 h.

Postoperative Care

Patients were transferred to ICU and epidural analgesia was given. Patients were allowed orally after recovery from general anesthesia. Early chest exercise and mobilization was done. Suction drain was removed after the fourth or fifth day and stiches removed after the tenth day.

Case 1

A 56-year-old male patient presented to outpatient clinic with a progressive sternal mass since 2 months. On examination, it was a 6 × 5-cm mass over sternum and was hard in consistency. The patient was a known asthmatic and was on bronchodilators. A CT abdomen and thorax showed left kidney growth and tumor involving the manubrium. A core biopsy of the bony lesion was suggestive of metastasis. Radical nephrectomy and resection of manubrium was performed. Reconstruction was done by mobilizing bilateral pectoralis major muscles by dividing at axilla and was reinforced with polypropylene mesh. The patient was on ventilator postoperatively for 2 days and recovered uneventfully. He had no signs and symptoms of paradoxical breathing and was discharged on the 12th postoperative day. On follow-up for a period of 2 years, he had optimal function for his routine activities without disability.

Steps in resection of sternal tumor: (1) sternal mass, (2) partial sternal resection, (3) defect following resection, (4) reconstruction with mesh, (5 and 6) mobilization of pectoralis major muscle, and (7) postoperative appearance (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7).

Case 2

A 72-year-old male who underwent thyroidectomy for papillary carcinoma thyroid 5 years ago had recurrence in the upper sternum. On examination, there was a 7 × 8-cm fixed mass in the upper sternum and medial third of right clavicle. MRI was done to know soft tissue extension. Radioiodine ablation was not feasible in view of bulky tumor. Wide excision with a margin of 3 cm was performed and resulted in excision of upper half of sternum and medial end of right clavicle. Reconstruction was done by transposed pectoralis muscles and meshplasty. He had an hospital stay of 10 days and was discharged uneventfully. The steps were as described above. On follow-up, he was given radio ablation scan. The functional outcome is good on follow-up for a period of 36 months.

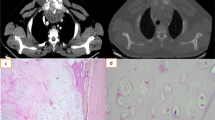

Case 3

A 43-year-old male presented with an ulcer over sternum. He had a swelling over sternum which was excised twice before and resulted in a non-healing ulcer. On examination, there was a 4 × 5-cm ulcer fixed to underlying sternum with no cortical breach. Radiological evaluation showed 6 × 5-cm soft tissue mass over sternum at the level of cardia and involving third and fourth ribs laterally on the left side. Trucut biopsy revealed a spindle cell lesion, high grade, and probably synovial sarcoma. The pathologist could not categorize further. Radical excision of the tumor resulted in resection of outer table of sternum and third, fourth, and fifth ribs for a distance of 5 cm. The resultant defect was reconstructed with vertical myocutaneous rectus abdominus flap. He had uneventful recovery and was discharged on the seventh postoperative day. Histopathology was suggestive of high-grade synovial sarcoma. On follow-up for 16 months, he had good functional and aesthetic result (Figs. 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15).

Case 4

A 47–year-old female presented with a bony hard parasternal mass. Radiological evaluation revealed a primary bony tumor involving third rib and lateral border of sternum on the left side. Trucut needle biopsy could not specify the tumor type. Wide excision done by removing third and fourth ribs and left lateral border of sternum of about 2 cm width and 4 cm length. Mesh plasty with primary closure was done. Postoperative recovery was uneventful. Histopathological report came as chondrosarcoma. On follow-up for a period of 2 years, the patient was disease-free with normal functional outcome (Figs. 16, 17, 18, and 19).

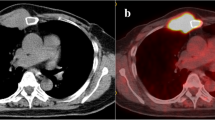

Case 5

A 54-year-old man presented with swelling in the right clavicle. Evaluation revealed it as a metastatic tumor, adenocarcinoma with unknown primary. Radiological evaluation showed the tumor at the medial end of clavicle and involvement of sternum up to manubrium. A T-shaped incision was given, and wide resection of medial end of clavicle along with manubrium is done. Pectoralis major muscle is mobilized to cover the defect. Postoperative period was uneventful (Figs. 20, 21, 22, and 23).

Discussion

Radical excision is indicated in primary tumor and solitary metastases of sternum. Adequate reconstruction after resection is essential for prevention of pulmonary and chest complications such as flail chest or paradoxical breathing. Resection and reconstruction can be challenging for the surgeon. Sternal defects may be partial longitudinal, subtotal lower, upper, or mid sternectomies. Partial longitudinal sternectomies do not need reconstruction where as sternectomies involving entire width need reconstruction. Patients undergoing a partial longitudinal sternectomy of maximally 50% of the sternal width do not necessarily require a rigid reconstruction, regardless of the part of the sternum involved .Reconstruction can be rigid or nonrigid. The choice of the type of reconstruction usually depends on the surgeon’s preference. The use of methacrylate and polypropylene mesh as a sandwich is most often employed for a stable reconstruction [7], but there is no evidence that this gives optimal functional outcome. In this article, we have done reconstruction without a stable construction but still resulted in optimal functional outcome. In our opinion, a nonrigid reconstruction in the anterior chest wall of partial sternectomies does not compromise the pulmonary functions. Even though rigid reconstructions do provide stability they may not help in pulmonary functions as even in rigid reconstructions studies have shown significant pulmonary complications [7]. In his study, Deschamps et al. [8] have shown the morbidity associated with prosthetic chest wall reconstruction includes seroma, local infection, systemic sepsis, and graft necrosis and infection. Though small in number, there was no such complication in our series. Prosthetic placement may by itself interfere with local imaging during follow-up period and also in interpreting the images. Moreover, in the series of cases which we have mentioned, all were partial sternal defects. Methacrylate might be a very good option after total sternectomy or for larger defects [9], though large defects can also be reconstructed with musculocutaneous flaps as well as stated by Alain chapelier [10]. In partial defects, musculocutaneous flaps might be a good and safe option. In the updated series of 38 cases by Chapelier AR et al., flap-related complications were not observed and local septic complications requiring removal of the composite prosthesis with reoperations [6]. In a study of 52 cases by Incarbone et al. [11], 15% had local complications including seroma formation and removal of prosthesis in two cases and necrosis of the wound which required debridement and coverage by a muscle flap. With this background, local muscle flaps might play a vital role in reconstructing as well avoiding the abovementioned problems.

Conclusion

Local recurrences are minimized by wide resections. Large sternal defects can be safely reconstructed with a musculocutaneous flaps over polypropylene mesh without causing respiratory insufficiency.

References

Anderson BO, Burt ME (1994) Chest wall neoplasms and their management. Ann Thoracic Surg 58:1774–1781

Noguchi S, Miyauchi K, Nishizawa Y, Imaoka S, Koyama H, Iwanaga T (1988) Results of surgical treatment for sternal metastasis of breast cancer. Cancer 62:1397–1401

Kluiber R, Bines S, Bradley C, Faber LP, Witt TR (1991) Major chest wall resection for recurrent breast carcinoma. Am Surg 57:523–530

Jurkiewicz MJ, Bostwick J III, Hester TR et al (1980) Infected median sternotomy wound. Successful treatment by muscle flaps. Ann Surg 191(6):738–743

Nakamura H, Kawasaki N, Taguchi M, Kitaya T (2007) Reconstruction of the anterior chest wall after subtotal sternectomy for metastatic breast cancer: report of a case. Surg Today 37(12):1083–1086

Alain R (2004) Chapelier sternal resection and reconstruction for primary malignant tumors. Ann Thorac Surg 77(3):1001–1007

Briccoli A, Manfrini M, Rocca M, Lari S, Giacomini S, Mercuri M (2002) Sternal reconstruction with synthetic mesh and metallic plates for high grade tumors of the chest wall. Eur J Surg 168:494–499

Deschamps C, Tirnaksiz BM, Darbandi R, Trastek VF, Allen MS, Miller DL, Arnold PG, Pairolero PC (1999) Early and long-term results of prosthetic chest wall reconstruction. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 117:588–592

Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian, Wai Ke, Za Zhi. Application of titanium plate and Teflon patch in chest wall reconstruction after sternal tumor resection. 2011;25(10):1224–6.

Chapelier A et al (2010) Resection and reconstruction for primary sternal tumors. Thorac Surg Clin 20(4):529–534

Incarbone M, Nava M, Lequaglie C, Ravasi G, Pastorino U (1997) Sternal resection for primary or secondary tumors. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 114:93–99

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the patients who are included in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arjunan, R., Veerendrakumar, K., Sailaja, S. et al. Partial Sternal Resections in Primary and Metastatic Tumors with Nonrigid Reconstruction of Chest Wall. Indian J Surg Oncol 8, 284–290 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13193-017-0632-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13193-017-0632-7