Abstract

Communication skills training can enhance health professionals’ knowledge and repertoire of effective communication practices. This paper describes the conceptual model underlying a 3-day retreat communication skills training program, methods used for training, and participant perception of outcomes from the training using qualitative interviews. Repeated qualitative telephone interviews (approximately 6 months apart) with participants of a 3-day Clinical Consultation Skills Retreat. Fourteen participants (70% response, 57% doctors) took part at Time 1, with 12 participating at Time 2. Semi-structured interviews were recorded and transcribed, and directional content analysis was conducted to assess themes in areas of key learnings, implementation of skills, and barriers. The training was received very positively with participants valuing the small group learning, role play, and facilitator skills. Key learnings were grouped into two themes: (i) tips and strategies to use in clinical practice and (ii) communication frameworks/methods, with the second theme reflecting an awareness of different communication styles. Most participants had tried to implement their new skills, with implementation reported as a more deliberate activity at T1 than at T2. Those implementing the new skills noted more open conversations with patients. Practical barriers of lack of time and expectations of others were mentioned more often at T2. A 3-day retreat-based communication training program was positively received and had a positive impact on the use of new communication skills. While further work is needed to determine whether effects of training are evidenced in objective clinical behaviors, the positive longer-term benefits found suggest this work would be worthwhile.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Effective communication between health professionals and patients and their family members/carers is recognized as an essential component of quality health care [1]. To this end, in 2017, the American Society of Clinical Oncology released consensus guidelines for patient-clinician communication highlighting the role patient-centered communication has in improving outcomes for patients [2]. In Australia, effective patient-health professional communication is recognized as a core component of quality cancer care, with federal and state government-endorsed optimal care pathways (OCP) recognizing health care systems have an obligation to meet patient communication needs [3].

Health professionals often need additional support to assist them in their communications with patients, especially in the delivery of bad or difficult news [4]. Communication skills training has been advocated as a strategy to enhance health professionals’ knowledge and repertoire regarding effective communication practices [2, 5], and the latest version of Australia’s OCPs recognizes the potential of training to enhance clinicians’ communication skills. While many programs have been developed, components are generally similar and include defining essential components for effective communication (e.g., use of open questions, conveying empathy, comfort with silence), learning through observation, role-play, and practice and structured feedback and self-reflection [6, 7]. Small group learning and skilled facilitators to model the desired communication skills and facilitate experiential learning exercises are also recommended [6, 7].

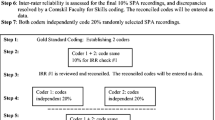

This paper reports the experiences of oncology healthcare professionals’ participation in a 3-day communication training program run as a retreat (referred to as the retreat). The retreat provides the opportunity for participants to apply core communication skills across the care trajectory—from diagnosis to end-of-life. Using small group learning principals that involved 4–6 participants working with one facilitator and a learner-centered approach, participants identify individual communication challenges with experiential role-play tailored to reflect their needs, interests, and health professional backgrounds. Simulated case studies containing both disease and illness elements are used to ensure participants practice patient-centered clinical interviewing [2, 8]. The simulated case (played by paid actors) are rich with contextual factors (e.g., responsibilities, social support, and access to care) to ensure an understanding of the patient’s context including an exploration of values and goals and how these factors influence care planning and decision-making [9]. The case study is visited at various time points in clinical care, with common themes arising at each time point such as responding to emotion or facilitating shared decision-making, identified areas for exploration. The Calgary-Cambridge Agenda Led Outcome-Based Analysis (ALOBA) model is used to structure and facilitate communication skills training [10] (see Fig. 1 for structure and content of the retreat). Facilitators were senior clinician-academics with between 15 and 25 years of experience in delivering health communication training to a diverse range of health professionals and disciplines.

This paper presents findings from qualitative interviews to assess the impact of participation in the retreat on communication behaviors in the clinic in the short and longer term and to understand barriers participants identify to implementing their skills in the clinic.

Method

Design

Longitudinal, qualitative telephone interviews with participants from a 2019 Clinical Consultation Skills Retreat (the retreat). Qualitative method from a critical realist position was employed to allow a deeper understanding of participants’ learning experiences and implementation of skills [11].

Retreat Training

The retreat ran from Monday to Wednesday at a regional conference center, with participants staying onsite.

Recruitment

At the end of the retreat, participants were provided with information about the study including participating in two telephone interviews. Interested participants provided written consent to be contacted about the interviews.

Interviews

Semi-structured interviews included open-ended questions assessing experiences and outcomes from the retreat. Open-ended questions in Interview 1 (T1, approximately 4–6 weeks post-training) assessed impressions of the training program, including facilitators, use of actors for the role plays, and small group learning. Similar open-ended questions were used in Interview 2 (T2, 6 months after T1) to assess key learnings, implementation of learnings, outcomes, and barriers. All interviews were conducted by the same female behavioral researcher (Author 1) with a PhD and over 20 years of experience working in cancer control and support. Interview 1 lasted on average 31 (range: 21–41) min, and Interview 2 had an average of 21 (range: 12–31) min (see Supplementary Table 1 for relevant T1 and T2 interview questions).

Procedure

Potential participants were contacted by email from Author 1 (interviewer), provided with the study’s plain language statement, and invited to take part. Interview times were arranged after study consent obtained.

Consenting participants were contacted at the agreed time, and after obtaining verbal consent for audio recording, the interview commenced. At interview end, participants reconfirmed consent to take part in the second interview. Procedures for the second interview followed those for Interview 1, with the interviewer contacting participants by email and after obtaining consent, arranging an interview time. Interviews were conducted over the telephone and audio recorded with participant consent. The study had ethical approval from the organization ethics committee (IER: 1914). Reporting follows the COREQ guidelines.

Analysis

Audio recordings were transcribed and inductive, reflexive thematic analysis undertaken [11] with NVivo™ used to manage data and coding. Interviews were considered both cross-sectionally (i.e., Interview 1 or 2) and longitudinally for each participant. Three predetermined topic areas were established reflecting the interview schedule and study aims: “Key learnings,” “Implementation of learnings, outcomes and barriers,” and “Perceptions of Format” (Interview 1 only). After data familiarization, a coding scheme was developed (Author 1) which was reviewed, tested, and discussed with all team members. After the finalization of the coding scheme, the data were coded, and themes and subthemes were developed with discussion and checking at a team level. The saturation of major themes identified for each topic area was reached.

Results

Participants

Twenty people participated in the training program, with 14 taking part at T1 (response rate 70%, 11 (8 (79%) female)) and 12 participating (10 (83%) female) at T2. Eight participants were medical doctors from a range of specialities including anesthesia (n=2), geriatrics (n=1) palliative care (n=2), pain management (n=1), radiation oncology (n=1), and intensive care (n=1). Other participants included nurses (n=4), social work (n=1), and hospital management (n=2). Retreat attendance for three participants was funded by their employer; three (two nurses, 1 doctor) received grants to attend, with the remaining participants using Continuing Medical Education funding Footnote 1 to fund participation.

Topic Area 1: Key Learnings

Key learnings were grouped into two main themes: (i) skills/strategies to employ in clinical practice and (ii) communication frameworks/methodology. Table 1 presents the key learnings from the two interviews. Theme 1 reflected participants’ focus on the communication skills (e.g., value of silence/allowing pauses (n=5)) learned through the retreat. There was some change in the skills mentioned over time: “pausing” was common at both interviews, while “listening,” “chunking and checking,” and the use of “I wish” statements were mainly mentioned at T2. The second theme, “communication frameworks/methodology,” reflects participants growing awareness of communication methods and frameworks, their own communication style, and how they respond to different conversations. Exemplar quotes are as follows:

My key learnings were probably around how I might approach difficult conversations or how I might structure my sentences and the way I might ask a question or try and tease out more information from someone. (T1) (social worker)

The key learnings were the methodology of the communication skills, for example, different tools to use for communicating with patients. Something I find I do a lot more is chunking information to patients. I find that a very useful tool. (T2) (specialist doctor)

Topic Area 2: ‘Implementation of learnings, outcomes and barriers’

Implementing Skills into Practice

Most participants had tried to implement the communication skills into practice. While this was seen as a more deliberate activity at T1, by T2, many skills were employed more regularly. At each interview, several participants discussed the implementation of communication skills in relation to them having greater awareness of their communication practices.

Communication Outcomes

Two themes were identified: “patient outcomes” and “communication with other professionals.” In the “patient outcomes” theme, participants discussed how the new skills had allowed more open and responsive conversations with patients, which allowed patients to raise issues that they thought would not be discussed otherwise. For those in palliative care, the new skills enabled the opening up of end-of-life care discussions. The second theme “communication with other professionals” reflected the utility of the communication skills in their broader professional life including conversations with staff and in developing and maintaining relationships with colleagues (see Table 2 for exemplar quotes).

Barriers

At T1, most participants thought they were able to implement the new learnings into clinical practice, although there was recognition of factors that could make this more difficult. A key barrier reported at T1 and T2 was the clinical role participants had, with this most evident in comments by intensive care specialists and anesthetists. Anesthetists indicated a lack of time due to multiple clinicians needing to see patients before surgery.

At T2 there was greater recognition of the practical barriers with more participants mentioning a lack of time due to the pace and demands of work, expectations of other health professionals, and patients as barriers. Some noted that the pace of work meant they could not plan conversations ahead of time and reverted to their old practices.

Topic 3: Perceptions of the Retreat’s Format

Comments on the retreat’s format were categorized into three main areas. Exemplar quotes for each area are shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Small Group Learning

This approach enabled the development of trust and allowed participants to feel “safe making mistakes” and “be more authentic.” Several felt they would not have been able to try new approaches if they were constantly changing groups. Most groups consisted of the same health profession, with one including a mix of doctors, nurses, and allied health professionals. While some in this group commented the mix reflected the multidisciplinary nature of oncology care others expressed some initial concerns. However all thought the facilitator’s skills ensured scenarios were challenging and relevant to all group members, and all were satisfied with the learnings achieved.

Simulated Patients

All participants thought the simulated patients were integral to the success of the training program as they enabled the experiential learning to reflect practice as much as possible and allowed skills learned to more easily transfer into clinical practice.

Facilitators

Participants noted facilitators were highly skilled communicators both clinically and as educators, and this assisted in the overall experience of the retreat.

Discussion

Using qualitative interviews at two time points, this study examined the immediate and longer-term impact of participation in a 3-day retreat-style communication skills training program on the communication practices of oncology health professionals. Similar to others [12,13,14,15], the training program assessed had an immediate positive impact on health professionals’ awareness of their communication styles and use of new communication skills. Data from the second interview suggests that while, with time, the new skills became more internalized, there was also greater awareness of the barriers to using these skills, with the key barriers being the type of work professionals were involved with, patient and colleagues’ expectations, and the busyness of clinical practice. While further work is needed to determine whether the impact of the program found here is evidenced in objective clinical behaviors, the positive longer-term benefits reported by participants suggest this work would be worthwhile.

Careful consideration was given to the training’s format, the development of the simulated case study, the choice of facilitators, actors, and learning activities. Skills-based communication approaches aim to change communication behavior, requiring experiential practice to allow clinicians to practice skills, and to see how they can be integrated into practice. The ALOBA methodology for experiential role play provides a framework for analyzing simulated clinical encounters and giving feedback that maximizes learning and learner safety [16]. The retreat’s learner-centric approach and use of experiential learning with simulated patients were seen to be effective by all participants. The facilitators’ skills in running the small group learning were integral and frequently mentioned as a strength of the training.

The retreat was made available to any health professional working in oncology allowing health professionals from a range of specialty disciplines to attend. While the majority of attendees and study participants were medical doctors, nurses, allied health, and hospital administrators attended the retreat and were interviewed for this study. The number of participants at the retreat was capped to ensure groups of up to 6 participants worked with an assigned facilitator across the entire retreat. As most retreat participants were doctors, most groups contained only doctors. Only one group contained a mix of different health professional disciplines. Given the multidisciplinary nature of oncology care developing communication programs that enable different specialities to learn together may promote awareness of the different skills different health professions bring to the care of patients and the benefits of all being skilled communicators. The similarity of experiences and impact of the training across different health professionals found in our study suggests that the retreat’s learner-centric approach is effective regardless of the health professional background.

Findings from the two interviews suggested there was an integration of skills into regular practice with time. At T1, most participants spoke about including the new skills into clinical practice as a conscious effort. By the second interview, there was a sense that many skills were being used more regularly in practice with a greater number of communication skills mentioned as key learnings. While fewer people mentioned the theoretical methods or the communication acronyms as key learnings at T2, a number spoke of the micro-skills learned during the retreat.

Good communication skills training includes developing participants’ awareness of the communication context and skills in determining when to implement different skills to achieve an outcome appropriate for the patient and clinician [7]. Many participants in this study demonstrated a growing awareness of these issues, speaking about their emotional responses needing to be considered, awareness of their own communication styles, and being aware of when they can and cannot implement the communication skills.

Barriers to implementing the new skills were a mix of the practical considerations of time, structure of work, and to some extent expectations of colleagues. While the workplace was generally not seen as hindering good communication skills, there was recognition that some structural barriers and work routines involving other clinicians made implementation difficult. These difficulties were noted in some critical care specialties, and while they need to be confirmed, they may suggest more specific training focusing on work practices in these specialties is needed.

Several limitations need to be noted. The study did not assess patient experiences with clinicians to understand whether patients noted a difference or a benefit from healthcare professionals’ enhanced or new communication skills. Study participants were drawn from one retreat program, and findings may reflect the facilitators and participants at this retreat. More studies involving larger samples from retreat-based training programs are needed. The number of participants taking part in both interviews was relatively small. While saturation of major themes was achieved, saturation may not have been reached when assessing the key learnings from the retreat. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 and the restrictions and refocus of the health system to deal with this meant clinicians’ experiences with patients at face-to-face appointments were limited by T2.

This study demonstrates that a 3-day communications skills training program utilizing a small group, learner-centric approach, and practice with simulated patients can increase health professionals’ awareness of their communication style, barriers to communicating effectively with patients, and self-efficacy for empathic communication.

Notes

Continuing Medical Education funding. In recognition of the need for medical staff to maintain their expertise and knowledge of current practice, medical staff at public hospitals in Victoria, Australia, receive an annual allowance to fund attendance at accredited training programs/conferences.

References

Bos-van Hoek DW, LNC V, Brown RF, EMA S, Henselmans I (2019) Communication skills training for healthcare professionals in oncology over the past decade: a systematic review of reviews. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 13(1):33–45. https://doi.org/10.1097/spc.0000000000000409

Gilligan T, Coyle N, Frankel RM et al (2017) Patient-clinician communication: American Society of Clinical Oncology consensus guideline. J Clin Oncol 35(31):3618–3632. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2017.75.2311

Bergin RJ, Whitfield K, White V et al (2020) Optimal care pathways: a national policy to improve quality of cancer care and address inequalities in cancer outcomes. J Cancer Policy 25:100245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcpo.2020.100245

Banerjee SC, Manna R, Coyle N et al (2017) The implementation and evaluation of a communication skills training program for oncology nurses. Transl Behavioral Med 7(3):615–623. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-017-0473-5

Noble LM, Scott-Smith W, O’Neill B, Salisbury H, O’Neill B (2018) Consensus statement on an updated core communication curriculum for UK undergraduate medical education. Patient Educ Counsel 101(9):1712–1719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.04.013

Moore PM, Rivera S, Bravo-Soto GA, Olivares C, Lawrie TA (2018) Communication skills training for healthcare professionals working with people who have cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7:Cd003751. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003751.pub4

Stiefel F, Kiss A, Salmon P et al (2018) Training in communication of oncology clinicians: a position paper based on the third consensus meeting among European experts in 2018. Ann Oncol 29(10):2033–2036. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy343

McWhinney IR (1986) Are we on the brink of a major transformation of clinical method? CMAJ 135(8):873–878

Weiner SJ, Schwartz A (2016) Contextual errors in medical decision making: overlooked and understudied. Academic Med 91(5):657–662

Kurtz S, Silverman J, Benson J, Draper J (2003) Marrying content and process in clinical method teaching: enhancing the Calgary-Cambridge guides. Acad Med 78(8):802–809

Braun VC (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Res in Psych 3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Banerjee SC, Haque N, Bylund CL et al (2021) Responding empathically to patients: a communication skills training module to reduce lung cancer stigma. Transl Behavioral Med 11(2):613–618. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibaa011

Paladino J, Kilpatrick L, O'Connor N et al (2020) Training clinicians in serious illness communication using a structured guide: evaluation of a training program in three health systems. J Palliat Med 23(3):337–345. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2019.0334

Pehrson C, Banerjee SC, Manna R et al (2016) Responding empathically to patients: development, implementation, and evaluation of a communication skills training module for oncology nurses. Patient Educ Couns 99(4):610–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.11.021

Bylund CL, Banerjee SC, Bialer PA et al (2018) A rigorous evaluation of an institutionally-based communication skills program for post-graduate oncology trainees. Patient Educ Couns 101:1924–1933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.05.026

Kurtz SM, Silverman J, Draper J (2005) In: van Dalen J, Platt FW (eds) Teaching and learning communication skills in medicine, 2nd edn. Radcliffe Pub.

Acknowledgements

The project could not have been done without the participation of the clinicians and health professionals who took time from their busy workdays to participate in the interviews conducted for this study. As interviews were requested at a time of increased demands on the health systems due to the COVID-19 pandemic, their time and involvement are greatly appreciated.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. The work was funded by Cancer Council Victoria.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: VW, AP, EW, MC, PM. Data analysis and interpretation: VW, AP, EW. Drafting the article: VW, MC, PM. Critical revision of the article: VW, MC, PM, EW, AP. Final approval of the version to be published: VW, MC, PM, EW, AP.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards approved by Cancer Council Victoria’s Institutional Research Review Committee (IER 1914).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1:

Supplementary Table 1: Questions used in Interview 1 and Interview 2. Supplementary Table 2: Exemplar quotes relating to the format of the training program. (DOCX 24 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

White, V., Chiswell, M., Webber, E. et al. What Impact Does Participation in a Communication Skills Training Program Have on Health Professionals’ Communication Behaviors: Findings from a Qualitative Study. J Canc Educ 38, 1600–1607 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-023-02305-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-023-02305-9