Abstract

Introduction

AGA guidelines emphasize split-dose bowel preparation (BP) to ensure high-quality colonoscopy for the prevention of colorectal cancer (CRC). Split dose results in higher-quality preparation, but understanding instructions might be more difficult. Lower education levels may negatively influence BP quality. The confounding role of education level on BP quality was investigated.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study of 60 patients given split-dose BP. Patients consented and were asked three Likert scale questions based on BP instructions before the procedure. Compliance was self-reported. BP adequacy and the number of adenomas were recorded. BP was characterized as adequate (excellent, good) or inadequate (fair, poor). Data was analyzed with chi-square, odds ratio, Mann-Whitney, and regression analysis.

Results

Thirty-one (52%) patients were high school graduates, 21 (38%) completed some college, and 6 (10%) were college graduates. College-educated patients had adequate BP (72%) more often than high school graduates (51%) (p = 0.02). Adenoma findings were not significantly different. The Likert scale mean ranks for patient understanding and reviewing of instructions were comparable between the two groups. Patient rating of scheduler explanations of the importance of following instructions was significantly better in the college group (mean ranks 2.59 and 1.83, respectively; p = 0.018).

Discussion

Patient education level significantly affected the success of BP. Split BP can be more complex to comprehend, and instructions should consider patient education level. Specific intervention programs should be implemented to advise patients with less education that poor preparation may result in missed advanced neoplasias and subsequent procedures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a leading cause of death worldwide. In recent years, CRC mortality has been on a decline due to the efficacy of routine colonoscopies in detecting early cancers [1]. There has been a move towards the use of open access colonoscopies in recent years although the use of split preparation may complicate patient understanding in this setting [2]. The 2020 American Gastroenterological Association guidelines place a large emphasis on split-dose bowel preparation (BP) to ensure high-quality colonoscopies [3] as up to 25% of all colonoscopies suffer from inadequate prep [4]. Although mixed results have been published, split preparation increases the quality of bowel preparation compared to whole dosing [5]. The application of split preparation closer to scoping of the bowel results in reduced interference of chyme in the colon [6] and has also been found to improve compliance, adenoma detection rate (ADR), and patient satisfaction [3, 7]. Therefore, split dosing results in higher-quality preparation, but understanding instructions might be more difficult.

Several clinical and socioeconomic factors play a role in patient compliance with colonoscopy BP including education level, health literacy, and medication burden, among other factors [8]. There is a correlation between low patient education levels and poor health literacy [9]. Furthermore, low patient engagement in their health correlated with poor bowel preparation [10]. Despite a few studies, there is limited literature investigating the role of patient education level on split-dose BP outcomes.

The discovery of COVID-19 viral transmission through fecal shedding has led to the postponement of non-emergent colonoscopies [11,12,13]. As operations return, it is expected that endoscopy centers will have a backup of patients needing to be seen on top of added space restrictions [14]. In a previous study, we identified that high-quality colonoscopies can be achieved through an open access (OA) approach. OA procedures are a suitable option to lessen the patient load on GI practices, as primary care physicians can manage patient instruction to ensure adequate BP, while GI providers can more efficiently utilize their time to complete procedures. However, patient education level poses a threat to the adequacy of BP in OA colonoscopies. It has been shown that a lower patient education level corresponds with a poorer quality of bowel preparation [15, 16].

Patient education level can influence the extent to which instructions are understood and followed. In this study, the confounding role of education level in split prep colonoscopy compliance, adequacy, ADR, and patient perception was investigated. We aim to provide appropriate changes to bowel preparation protocol and instruction to improve outcomes regardless of patient education level. CRC prevention can be greatly improved if shortcomings in patient instruction surrounding bowel preparation are addressed.

Methods

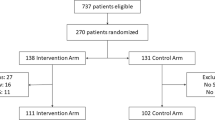

This was a cross-sectional prospective study of 60 patients, all given split-dose BP for both surveillance and screening colonoscopies. Patients were seen at Albany Medical Center, where almost 10,000 endoscopic procedures are done per year. If time and logistics allowed for patient participation in the study, permission was obtained by a pre-op nurse. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Standardized written instructions were given to each patient regardless of education level, although verbal instructions provided by the scheduler likely varied. To minimize recollection or physician bias, a research assistant administered surveys preoperatively (Fig. 1). BP compliance was self-reported by the patient before the procedure, and BP adequacy and detection of adenomas (ADR) were recorded. BP was characterized as adequate (excellent, good) or inadequate (fair, poor). Patients were asked three questions qualifying the BP instructions—“Does the patient understand the importance of following the instructions?” “Did the scheduler explain the importance of the instructions?” and “Did the scheduler review the instructions?” (Fig. 2). These three questions were answered by the patient using a Likert scale from 1 to 5, with 5 indicating complete agreement with the statement, and 1 indicating no agreement. Patient age, sex, BMI, education level, history of constipation, and indication of colonoscopy were collected. SPSS 20.0 was utilized to analyze data using chi-square, Mann-Whitney, and regression analysis [17].

Results

Patient education level data was provided for 60 of the study participants. Of this population, 31 patients (52%) received a high school education, while 23 (38%) had completed some college and 6 (10%) were college graduates. Those with some college completion and college graduates were grouped together for analysis. There was no noted difference in the demographic characteristics between high school and college groups: age, sex, BMI, history of constipation, and prior colonoscopy (p > 0.05). Additionally, education level was not significantly different between the OA and GI office scheduling providers (Table 1).

Data was collected on the outcome variables of compliance with BP instructions, adequacy of BP, and the number of adenomas detected. It was found that patient education level is statistically significant in terms of BP adequacy (OR 4.32, p = 0.003). The same result was found using regression analysis (p = 0.04) (Table 2).

Education level did not significantly affect the number of adenomas or compliance with BP. Although compliance was comparable between the two groups, adequacy suffered in the high school cohort (Fig. 3). Higher education levels are associated with more adequate preparation. The mean age of the two groups was calculated and found to not be significant (p = 0.214) (Table 3).

College-educated patients reported better perceived explanation of the BP instructions compared to the high school group patients. The mean rank for “did the scheduler explain the importance of the instructions?” was 1.83 for the high school group compared to 2.59 for the college group (p = 0.018). No statistical difference was found between how well the patients perceived the explanation of instructions and how well the patients understood the importance of BP completion. The mean rank for understanding was 1.47 for the high school group compared to 1.52 for the college group (p = 0.07). The mean rank for the question “did the scheduler review the instructions?” was 2.23 for the high school group compared to 2.42 for the college group (p = 0.43) (Table 4).

Discussion

The results of this study indicate a significant effect of patient education level on compliance and success of colonoscopy bowel prep. Interestingly, BP adequacy did not align with compliance among patients with a lower education level, as there was no difference in self-reported compliance between the groups, but BP adequacy suffered in the high school education group. This suggests a disconnect between the understanding of BP requirements in patients with a lower education level, which ultimately impacted the operating physician’s ability to adequately report colonoscopy findings. Patients may have mistakenly believed they were properly completing the BP. Additionally, the complexity of split prep directions may have resulted in difficulties following the protocol. As a possible, yet unproven etiology for the lapse in adequacy, we hypothesize that a lower education level led to a poorer understanding of instructions which contributed to a difference in preparation. Further studies involving standardized instructional material may elucidate the exact effect that patient instructions have on bowel prep outcomes.

Upon review of the results of the Likert scale questions, we can pinpoint the areas for improvement in patient instruction. Patients with a lower education level reported poorer explanation of the importance of following instructions when compared to patients with a higher level of education. This shows an important lapse in the comprehension of the requirements of split preparation and completion of the necessary steps. It has been found that poor bowel preparations result in higher miss rates along with more frequent follow-up appointments, ultimately decreasing the effectiveness of colonoscopies and possibly increasing the risk of developing CRC [18]. We recommend that patients with a lower education level be informed of the consequences of poor preparation, such as potentially missed neoplasias and subsequent procedures. The level of patient education should be considered when explaining the requirements and importance of following BP instructions.

Overall, the mean rank scores for all questions regarding patient perception were lower than expected. This indicates a need for improved patient instruction in all areas of the bowel preparation process. We recommend that further research be completed to address specific measures for improved patient perception of BP.

COVID-19 has caused delays in the completion of colonoscopies, which can be mitigated through the use of OA. Patient education level presents a significant barrier to colonoscopy outcomes which can be extended to OA colonoscopies [8]. Improved patient instruction has the potential to decrease the incidence of repeat colonoscopies and enhance adenoma detection for CRC prevention in less educated patients with poor BP. With these improvements, less frequent follow-up appointments and procedures are needed. We predict that ensuring a minimal number of visits per patient will alleviate the back-up of appointments already complicated by COVID-19 scheduling conflicts. Furthermore, fewer points of contact can ensure safety for both office staff and patients and can be achieved by shorter interval times between colonoscopies.

There have been several other published studies highlighting possible interventions in patient instruction to improve BP and colonoscopy findings. A review of patient instruction improvements found that counseling sessions between patients and providers were significant in communicating the expectations of BP and resulted in greater quality of preparation upon the procedure. Other studies mentioned in this analysis have explored the use of multimedia, such as educational videos or SMS reminders, to help patients remain informed and consistent with the requirements for bowel preparation [19]. It has been found that 10-min conversations surrounding preparation details given along with written instructions significantly improve the quality of BP when compared to the absence of counseling sessions [10, 20]. Further studies found that written instruction leaflets were better than verbal BP instructions [21]. Additional research and intervention are needed to define the best approaches to closing this gap in understanding.

Furthermore, we suggest the future use of the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT) to confirm the accessibility and actionability of print and audiovisual materials given to patients prior to bowel preparation. The PEMAT is a tool used to improve health literacy and the efficacy of patient education materials [22] and has been shown to provide a valuable assessment that addresses differences in patient reading level [23].

Our study is a cross-sectional, unbiased study investigating the factors affecting split bowel preparation success. It is unique in discussing the specific role of split-dose prep on outcomes while taking perioperative patient perception into account. The main limitations of our study are the small sample size and a single-center study population. Additionally, patient cancelations and no-shows were not accounted for. Although these limitations exist, this study highlights an important aspect of split bowel preparation that can ensure improved outcomes if addressed.

Conclusion

Patient education level plays an important role in the adequacy of split bowel preparation. Lower education levels are associated with a poor understanding of instructions, which directly affects procedure outcomes. The COVID-19 pandemic has emphasized the use of open access colonoscopies, although education level hinders the achievement of high-quality bowel preparations in these settings. Improved education can decrease the need for follow-up appointments for patients with previously inadequate prep. Patient education prior to procedures is a vital target for improvement in both primary care and GI offices. It is recommended that providers consider a patient’s level of education and adjust instructions accordingly. Changes in patient education can aid in the prevention of CRC and decrease the need for subsequent procedures due to missed neoplasias.

References

Dekker E, Rex DK (2018) Advances in CRC prevention: screening and surveillance. Gastroenterology 154(7):1970–1984

Ghaoui R, Ramdass S, Friderici J, Desilets DJ (2016) Open access colonoscopy: critical appraisal of indications, quality metrics and outcomes. Dig Liver Dis 48(8):940–944

Johnson DA, Barkun AN, Cohen LB, Dominitz JA, Kaltenbach T, Martel M, Robertson DJ, Boland CR, Giardello FM, Lieberman DA, Levin TR, Rex DK (2014) Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: recommendations from the US multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 147(4):903–924

Harewood GC, Sharma VK, de Garmo P (2003) Impact of colonoscopy preparation quality on detection of suspected colonic neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc 58(1):76–79

Enestvedt BK, Tofani C, Laine LA, Tierney A, Fennerty MB (2012) 4-Liter split-dose polyethylene glycol is superior to other bowel preparations, based on systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 10(11):1225–1231

Shine R, Bui A, Burgess A (2020) Quality indicators in colonoscopy: an evolving paradigm. ANZ J Surg 90(3):215–221

Bechtold ML, Mir F, Puli SR, Nguyen DL (2016) Optimizing bowel preparation for colonoscopy: a guide to enhance quality of visualization. Ann Gastroenterol 29(2):137–146

Kunnackal John G, Thuluvath AJ, Carrier H, Ahuja NK, Gupta E, Stein E (2019) Poor health literacy and medication burden are significant predictors for inadequate bowel preparation in an urban tertiary care setting. J Clin Gastroenterol 53(9):e382–e386

Paasche-Orlow MK, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nielsen-Bohlman LT, Rudd RR (2005) The prevalence of limited health literacy. J Gen Intern Med 20(2):175–184

Serper M, Gawron AJ, Smith SG, Pandit AA, Dahlke AR, Bojarski EA, Keswani RN, Wolf MS (2014) Patient factors that affect quality of colonoscopy preparation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 12(3):451–457

Gastroenterology Professional Society Guidance on Endoscopic Procedures During the COVID-19 Pandemic. COVID-19: ASGE updates for members [website] [cited 2020 June 1st]; Available from: https://www.asge.org/home/advanced-education-training/covid-19-asge-updates-for-members/gastroenterology-professional-society-guidance-on-endoscopic-procedures-during-the-covid-19-pandemic

Gralnek IM, Hassan C, Beilenhoff U, Antonelli G, Ebigbo A, Pellisè M, Arvanitakis M, Bhandari P, Bisschops R, van Hooft JE, Kaminski MF, Triantafyllou K, Webster G, Pohl H, Dunkley I, Fehrke B, Gazic M, Gjergek T, Maasen S, Waagenes W, de Pater M, Ponchon T, Siersema PD, Messmann H, Dinis-Ribeiro M (2020) ESGE and ESGENA Position Statement on gastrointestinal endoscopy and the COVID-19 pandemic. Endoscopy 52(6):483–490

Kushnir VM, Berzin TM, Elmunzer BJ, Mendelsohn RB, Patel V, Pawa S, Smith ZL, Keswani RN, North American Alliance for the Study of Digestive Manifestations of COVID-19 (2020) Plans to reactivate gastroenterology practices following the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey of North American centers. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 18:2287–2294.e1

Sultan S et al (2020) AGA Institute Rapid Recommendations for Gastrointestinal Procedures During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Gastroenterology 159:739–758.e4

Chan WK, Saravanan A, Manikam J, Goh KL, Mahadeva S (2011) Appointment waiting times and education level influence the quality of bowel preparation in adult patients undergoing colonoscopy. BMC Gastroenterol 11:86

Radaelli F, Paggi S, Repici A, Gullotti G, Cesaro P, Rotondano G, Cugia L, Trovato C, Spada C, Fuccio L, Occhipinti P, Pace F, Fabbri C, Buda A, Manes G, Feliciangeli G, Manno M, Barresi L, Anderloni A, Dulbecco P, Rogai F, Amato A, Senore C, Hassan C (2017) Barriers against split-dose bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Gut 66(8):1428–1433

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (2011) IBM Corp: Armonk, NY

Lebwohl B, Kastrinos F, Glick M, Rosenbaum AJ, Wang T, Neugut AI (2011) The impact of suboptimal bowel preparation on adenoma miss rates and the factors associated with early repeat colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 73(6):1207–1214

Liu Z, Zhang MM, Li YY, Li LX, Li YQ (2017) Enhanced education for bowel preparation before colonoscopy: a state-of-the-art review. J Dig Dis 18(2):84–91

Shieh TY et al (2013) Effect of physician-delivered patient education on the quality of bowel preparation for screening colonoscopy. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2013:570180

Andrealli A, Paggi S, Amato A, Rondonotti E, Imperiali G, Lenoci N, Mandelli G, Terreni N, Spinzi G, Radaelli F (2018) Educational strategies for colonoscopy bowel prep overcome barriers against split-dosing: a randomized controlled trial. United European Gastroenterol J 6(2):283–289

Shoemaker SJ, Wolf MS, Brach C (2014) Development of the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT): a new measure of understandability and actionability for print and audiovisual patient information. Patient Educ Couns 96(3):395–403

Vishnevetsky J, Walters CB, Tan KS (2018) Interrater reliability of the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT). Patient Educ Couns 101(3):490–496

Funding

Not applicable

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Not applicable

Availability of Data and Material

Not applicable

Code Availability

Not applicable

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Donovan, K., Manem, N., Miller, D. et al. The Impact of Patient Education Level on Split-Dose Colonoscopy Bowel Preparation for CRC Prevention. J Canc Educ 37, 1083–1088 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01923-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01923-x