Abstract

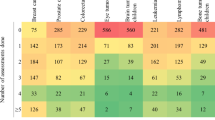

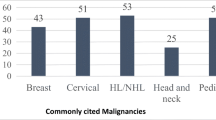

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the USA, but there is minimal data on how oncology is taught to medical students. The purpose of this study is to characterize oncology education at US medical schools. An electronic survey was sent between December 2014 and February 2015 to a convenience sample of medical students who either attended the American Society for Radiation Oncology annual meeting or serve as delegates to the American Association of Medical Colleges. Information on various aspects of oncology instruction at participants’ medical schools was collected. Seventy-six responses from students in 28 states were received. Among the six most common causes of death in the USA, cancer reportedly received the fourth most curricular time. During the first, second, and third years of medical school, participants most commonly reported 6–10, 16–20, and 6–10 h of oncology teaching, respectively. Participants were less confident in their understanding of cancer treatment than workup/diagnosis or basic science/natural history of cancer (p < 0.01). During the preclinical years, pathologists, scientists/Ph.D.’s, and medical oncologists reportedly performed the majority of teaching, whereas during the clinical clerkships, medical and surgical oncologists reportedly performed the majority of teaching. Radiation oncologists were significantly less involved during both periods (p < 0.01). Most schools did not require any oncology-oriented clerkship. During each mandatory rotation, <20 % of patients had a primary diagnosis of cancer. Oncology education is often underemphasized and fragmented with wide variability in content and structure between medical schools, suggesting a need for reform.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Leading causes of death. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm. Accessed 26 Mar 2015

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2015. http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/cancerfactsfigures2015/index. Accessed 26 Mar 2015

American Society of Clinical Oncology (2015) The state of cancer care in America, 2015: a report by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Oncol Pract 11:79–113

Onega T, Duell EJ, Shi X et al (2008) Geographic access to cancer care in the U.S. Cancer 112:909–918

Gaffan J, Dacre J, Jones A (2006) Educating undergraduate medical students about oncology: a literature review. J Clin Oncol 24:1932–1939

Tattersall MH, Langlands AO, Smith W et al (1993) Undergraduate education about cancer. A survey of clinical oncologists and clinicians responsible for cancer teaching in Australian medical schools. Eur J Cancer 29a:1639–1642

Oncology Education Committee (2007) Ideal oncology curriculum for medical schools. The Cancer Council Australia

Pavlidis N, Gatzemeier W, Popescu R et al (2010) The masterclass of the european school of oncology: the ‘key educational event’ of the school. Eur J Cancer 46:2159–2165

Pavlidis N, Vermorken JB, Stahel R et al (2012) Undergraduate training in oncology: an ESO continuing challenge for medical students. Surg Oncol 21:15–21

DeNunzio NJ, Joseph L, Handal R et al (2013) Devising the optimal preclinical oncology curriculum for undergraduate medical students in the United States. J Cancer Educ 28:228–236

Eysenbach G (2004) Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res 6(3), e34

Pavlidis N (1997) Undergraduate education in oncology in the Balkans and Middle East. The Metsovo Statement, April 4, 1997. Ann Oncol 8:1281

American Medical Association (2014) Physician characteristics and distribution in the U.S. 2014. American Medical Association, Chicago

Noonan K, Tong KM, Laskin J et al (2014) Referral patterns in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: impact on delivery of treatment and survival in a contemporary population based cohort. Lung Cancer 86:344–349

Bekelman JE, Suneja G, Guzzo T et al (2013) Effect of practice integration between urologists and radiation oncologists on prostate cancer treatment patterns. J Urol 190:97–101

The ESMO MOSES Task Force (2008) Medical Oncology Status in Europe Survey (MOSES). European Society for Medical Oncology. http://www.esmo.org/Policy/Recognition-and-Status-of-Medical-Oncology/Status-of-Medical-Oncology-in-Europe. Accessed 26 Mar 2015

Dennis KE, Duncan G (2010) Radiation oncology in undergraduate medical education: a literature review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 76:649–655

DeNunzio N, Parekh A, Hirsch AE (2010) Mentoring medical students in radiation oncology. J Am Coll Radiol 7:722–728

Berman AT, Plastaras JP, Vapiwala N (2013) Radiation oncology: a primer for medical students. J Cancer Educ 28:547–553

Agarwal A, DeNunzio NJ, Ahuja D et al (2014) Beyond the standard curriculum: a review of available opportunities for medical students to prepare for a career in radiation oncology. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 88:39–44

Hansen JT, Rubin P (1998) Clinical anatomy in the oncology patient: a preclinical elective that reinforces cross-sectional anatomy using examples of cancer spread patterns. Clin Anat 11:95–99

Hirsch AE, Handal R, Daniels J et al (2012) Quantitatively and qualitatively augmenting medical student knowledge of oncology and radiation oncology: an update on the impact of the oncology education initiative. J Am Coll Radiol 9:115–120

Zumwalt AC, Marks L, Halperin EC (2007) Integrating gross anatomy into a clinical oncology curriculum: the oncoanatomy course at Duke University School of Medicine. Acad Med 82:469–474

National Resident Matching Program (2014) Charting outcomes in the match, 2014. National Resident Matching Program, Washington, DC

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Cristin Watson, Assistant Director of Education at ASTRO, for her assistance in developing the survey tool, and the entire ARRO executive committee for their support of this project.

Funding

None to report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Fig. 1

(PDF 349 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mattes, M.D., Patel, K.R., Burt, L.M. et al. A Nationwide Medical Student Assessment of Oncology Education. J Canc Educ 31, 679–686 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-015-0872-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-015-0872-6