Abstract

NRF2 is a transcription factor that plays a pivotal role in carcinogenesis, also through the interaction with several pro-survival pathways. NRF2 controls the transcription of detoxification enzymes and a variety of other molecules impinging in several key biological processes. This perspective will focus on the complex interplay of NRF2 with STAT3, another transcription factor often aberrantly activated in cancer and driving tumorigenesis as well as immune suppression. Both NRF2 and STAT3 can be regulated by ER stress/UPR activation and their cross-talk influences and is influenced by autophagy and cytokines, contributing to shape the microenvironment, and both control the execution of DDR, also by regulating the expression of HSPs. Given the importance of these transcription factors, more investigations aimed at better elucidating the outcome of their networking could help to discover new and more efficacious strategies to fight cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 NRF2

Nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (NRF2) is a transcription factor that plays a pivotal role in cytoprotection, mainly because it induces the transcription of phase I and II phase I detoxification enzymes, limiting oxidative stress [1]. NRF2 activity is particularly important for the survival of cancer cells that, due to external and internal causes, are characterized by high level of reactive oxygen species (ROS), whose production may be further enhanced by exposure to anti-cancer treatments. Interestingly, NRF2 is considered a double face molecule, as its-activity, that helps to prevent tumor onset, can also sustains growth and survival of established tumor cells [2]. The canonical activation of NRF2 is caused by oxidative stress that induces the detachment of NRF2 from Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1), the most important negative regulator of NRF2 [3]. In this conditions, NRF2 free from the holding of KEAP1, can translocate into the nucleus, form heterodimers with one of the small Maf (musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog) proteins and recognize the antioxidant response elements (AREs), the enhancer sequences present in the regulatory regions of NRF2 target genes [4]. Once in the nucleus, NRF2, besides the de-toxifying enzymes, affects the transcription of a variety of molecules, as recently revised by Tonelli et al. [1]. NRF2 can be also stabilized by SQSTM1/p62, protein that promotes KEAP1 degradation [5]. This results in the non-canonical activation of NRF2, which can be the consequence of autophagy reduction, given that SQSTM1/p62 is a protein mainly degraded through autophagy and thus accumulates when such process is impaired [6]. Autophagy, is a self-eating mechanism, representing together with proteasome, the most important catabolic route of the cells. Basally activated in almost all cellular types, autophagy is particularly important in the survival of cancer cells that are forced to live in condition of shortage of oxygen and nutrients [7]. Moreover, the activation of NRF2 is regulated, through a feed-back mechanism, by Batch1, a transcriptional repressor of NRF2 activated by NRF2 itself [8].

2 STAT3

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) is a multifunctional transcription factor, classically activated by the Interleuchin-6 (IL-6)-type family cytokines, through Janus kinase (JAK) [9]. STAT3 establishes with IL-6 as well as with VEGF and IL-10, a positive feed-back loop, in which these cytokines activate STAT3 and this transcription factor, in turn, sustains their production. STAT3 interacts with several cellular pathways involved in cancer cell proliferation, progression and immune dysfunction. Aberrant activation of STAT3, due to phosphorylation of a tyrosine residue (Y705) and, in some cases of serine residue (S727), occurs in about 70% of cancers, either of solid and hematologic origin. STAT3 is generally considered to be an oncogene, although in some particular contexts, it may play a tumor suppressing role [10, 11]. Interestingly, the inhibition of STAT3 in cancer may give the double advantage to impair cell survival and concomitantly reactivate the anti-cancer immune response [12]. Of note, unphosphorylated STAT3 can also mediate the transcriptional activation of some genes, such as for example those encoding for STAT3 itself or those involved in the control of cell cycle progression [13].

Besides cytokines, STAT3 can be activated also by tyrosine kinases, such as v-Fps, v-Ros, Etk/BMX and v-Abl or by proteins encoded by oncoviruses such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) [14].

3 NRF2/STAT3 interplay involves p62/SQSTM1 and autophagy

The interplay between NRF2 and STAT3 is quite controversial and interestingly, it may also involve autophagy. Therefore, in this perspective, we will discuss the literature reports and attempt to shed some light on this interplay, particularly in the context of cancer cells.

Autophagy is a process controlled by several molecular pathways, including phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT/mammalian target of the rapamycin (mTOR) (PI3K/AKT/mTOR) [15] and STAT3 [16], whose impact on autophagy depends not only on the status of their phosphorylation, but also on their subcellular localization. Indeed, it has been reported that STAT3 cytoplasmic localization inhibits PKR activity and autophagy in osteosarcoma cells [17]. Moreover, in its unphosphorylated state, STAT3 may promote heterochromatin formation in lung cancer cells, suppressing cell proliferation [18]. Interestingly, autophagy may be dysregulated by external insults, for example microbial infection, either mediated by bacteria [19] or viruses [20], including the oncoviruses EBV, Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) and Hepatitis C Virus (HCV), as we have previously reported [21,22,23,24]. PI3K/AKT/mTOR and STAT3 are both considered to be mainly negative regulators of autophagy, as they can mediate an inhibitory effect on one or more of the different phases of the autophagic process. In this regard, we have previously observed that EBV infection of primary B lymphocytes [23] or KSHV infection of HUVEC cells [24] activate STAT3 and mTOR, respectively, to inhibit autophagy. As B lymphocytes and HUVEC are cells from which gammaherpesvirus-associated cancers arise, the inhibition of autophagy represents an important goal achieved by these viruses. Indeed, autophagy has been reported to put a brake on oncogenic transformation [25]. Moreover, it must be considered that autophagy promotes viral elimination through xenophagy [26], contributes to antigen presentation to dendritic cells (DCs) and to macrophages formation [27]. As it plays a key role in anti-viral immune response, autophagy inhibition by viruses may represent a defense mechanism. Moreover, they can also usurp the autophagic machinery for their own purpose, e.g. to facilitate the intracellular transportation of viral particles [28, 29].

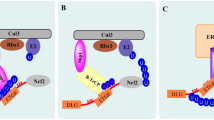

Among other consequences, the impairment of autophagy leads to SQSTM1/p62 accumulation [6], which promotes NRF2 stabilization and activation, upregulating the anti-oxidant response [30]. This represents a compensatory mechanism that allows restrain the increase of ROS occurring in autophagy-deficient cells, as it occurs for example in the case of EBV-infection of primary monocytes. In these cells, the increase of p62/SQSTM1, by leading to a reduction of ROS, impairs the in vitro differentiation of monocytes into dendritic cells (DCs) or macrophages [27]. p62/SQSTM1/NRF2 axis activation may thus represent a strategy exploited by EBV to inhibit the formation of cells, such as DCs, that play a key role in initiating an immune response towards a new antigen [31, 32]. From these evidences, it emerges that autophagy and p62/SQSTM1 may represent a link between mTOR and STAT3 activation and NRF2. Previous studies have started to explore some aspects of the relationship between NRF2 and mTOR [33], while in this perspective we will mainly focus on STAT3/NRF2 interplay. If, as said above, STAT3 may activate NRF2, through a STAT3/p62SQSTM1 axis (Fig. 1a), NRF2 may play an opposite effect, as it has been reported that AMPK-driven STAT3 inactivation involves Nrf2-small heterodimer protein (SHP) signaling cascade [34] (Fig. 2). Furthermore, among the components of the NRF2 interactome there is PPARγ, as NRF2 binds to its promoter, stimulating its transcription and engages with it a mutual feedback regulation [35]. Interestingly, PPARγ has been shown to induce STAT3 inactivation in pancreatic acinar cells [36].

4 Role of NRF2 and STAT3 in inflammation

Among the numerous processes controlled by NRF2, there is the inflammatory process [37], that, when lasts for long time, can sustain all steps of carcinogenesis [38]. NRF2 activation may reduce inflammation, as another compensatory mechanism through which cells attempt to defend themselves from oncogenic transformation, when autophagy is dysfunctional. Accordingly, we have found that the activation of NRF2 in primary B lymphocytes, in which the autophagic process is inhibited by EBV infection, restrains IL-6 cytokine production, besides lowering intracellular ROS [39], and both these effects counteract the in-vitro immortalization of B cells driven by the virus. The role of NRF2 in tumor prevention in this setting was supported by the experiments of silencing, pharmacological inhibition by Brusatol and on the other hand, by experiments in which NRF2 was activated by Sulforaphane. However, NRF2, depending on the initial steps of oncogenic transformation or in already transformed cells, can play opposite effects in carcinogenesis [2]. This difference mainly relies on the capacity of NRF2 to reduce ROS, which are the molecules most responsible for DNA damage, mutations and promotion of tumorigenesis, but are also those that can impair the survival of cancer cells, when their level become too high. It has been reported that the treatment by Dimethyl fumarate (DMF), an activator of NRF2, repressed JAK1 and STAT3 phosphorylation in hepatocellular carcinoma [40]. Accordingly, in a recent study, we have shown that NRF2 activation by DMF reduces ROS, IL-6 and IL-10 production by B lymphoma cells, resulting, also in this case, in a strong de-phosphorylation of STAT3 (Fig. 2) and in an impairment of cell survival [41]. These results suggest that it is not NRF2 that behaves differently during cancer formation or cancer survival/progression but are rather the effects that it produces that may play opposite roles in the different phases of tumorigenesis.

Interestingly, a recent study has reported that Brusatol can also lead to the inhibition of STAT3 and of that of the upstream kinases responsible for its activation, in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma [42], underscoring the complexity of NRF2 and STAT3 interplay in cancer and thus the difficulty to develop new drugs targeting these pathways [43]. Moreover, it should be considered that the specificity of Brusatol, commonly used to inhibit NRF2, remains to be better elucidated [44]. Of note, differently from NRF2, the activation of STAT3 can promote cell survival/proliferation, either during the first steps of carcinogenesis [23] and in established cancer cells [45,46,47], also because its activation may be sustained by NF-κB, as in the case of glioblastoma [48]. Another reason for such difference may be the fact that STAT3 promotes, rather than reducing, the production of pro-inflammatory and pro-angiogenetic cytokines such as IL-6 and VEGF, establishing with these cytokines a positive feed-back loop [49]. However, there are some cases in which STAT3 may play an anti-survival role, as reported, for example, in studies performed on mammary gland [50]. Moreover, among the other targets, STAT3 can also upregulate the expression of IL-6 inhibitory molecule Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling 3 (SOCS3) [51] and interestingly NRF2 has been reported to enhance SOCS3-dependent feedback inhibition on JAK2/STAT3, in hepatic stellate cells (Fig. 2) [52]. To recapitulate this complex landscape, it seems that the unbalance of NRF2 activation, either towards its hyperactivation or toward its inhibition, may affect STAT3 activation, cytokines release and the survival of cancer cells. Of note, cytokines may function not only as growth factors for several cancer cells that are responsible for their production, but may also strongly shape of the tumor microenvironment [53] and unbalance the pro-tumorigenic or anti-tumorigenic activity of immune system cells. For example, the release of cytokines such as IL-23, which may be regulated by STAT3 or by STAT3/NRF2 interplay can promote tumor growth [54] or contribute to immune dysfunction of dendritic cells, following KSHV infection [55]. Last but not least, cytokines may affect the activity of stromal cells such as fibroblasts and endothelial cells that may contribute to their production [56], and influence the progress of cancer [57].

5 NRF2 and STAT3 are influenced by post-translational modifications

Post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation, can strongly influence the activity of NRF2. Phosphorylation of NRF2 may occur at different residues and may be mediated by several kinases, resulting either in the activation or inhibition of NRF2 [58]. Among the kinases able to phosphorylate NRF2 there is Protein kinase R (PKR)-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) [59], one of the three Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) sensors, which can be activated in response to Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) stress. Therefore, besides autophagy, another adaptive response, namely UPR, impinges on the activation of NRF2. Of note, PERK can phosphorylate and activate also STAT3 [60]. Thus, it emerges that in stressed cells, the phosphorylation of both NRF2 and STAT3 may occur and usually contribute to cell survival. However, it is important to consider that NRF2 activation can be also inhibited in the course of UPR, through the activation of Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3beta) [58], highlighting once again the complexity of NRF2 regulation, also in stressed cells.

Among other post-translational modifications, methylation has been reported to influence NRF2 and STAT3 activity, as indeed methylation has been found to modify several nonhistone proteins including NRF2 and STAT3. Regarding NRF2, it has been shown that methylation can occur at arginine 437 residue and that this effect can moderately affect NRF2 activity [61, 62]. Regarding STAT3, it has been reported that it can be di- or trimethylated on K140 or K180 by the histone methyltransferase SET9 (SET domain containing lysine methyltransferase 9) or EZH2 (enhancer of zeste homolog 2), respectively, and that such post-translational modifications may affect STAT3-mediated transcription [63,64,65]. Interestingly, STAT3 can in turn regulates methylation of several promoters, as for example it promotes SOCS3 hypermethylation by increasing DNMT1 activity [66] and intriguingly, the acetylation of STAT3 may regulate its-mediated methylation [67]. These studies suggest the post-translational modifications of NRF2 and STAT3 are complex and context-specific, and thus deep investigations are required to clarify them.

6 NRF2 and STAT3 gene transcription may be regulated by methylation

Of note, methylation of NRF2 and STAT3 promoters can also influence the expression and activity of these transcription factors. For example, in the context of Alzheimer Disease, NRF2 activity is reduced by methylation and the DNA methyltransferases (Dnmts) inhibitor 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-Aza) may enhance NRF2 expression and transcriptional activity [68]. Regarding NRF2 methylation in cancer, it has been reported that no significant association could be found between NRF2 promoter demethylation and the clinicopathological features of colon cancer patient samples [69]. Another study has reported that sulforaphane, that promotes the demethylation of NRF2 promoter region, increases the activation of NRF2 in CaCo2 cells [70]. Regarding STAT3, it has been reported that 5-AZA may reduce its activation in acute myeloid leukemia cells by re-expression of silenced SHP-1, a negative regulator of the JAK/STAT pathway [71].

7 NRF2/STAT3 interplay affects DDR

An interesting point that deserves to be discussed is how the interplay between NRF2 and STAT3 affects the DNA damage response (DDR). In the physiological execution of DDR, Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs) plays a pivotal role, as many molecules, involved in both single- and double-stranded DNA breaks, are HSP clients [72]. For example, small HSPs, such as HSP27 can stabilize and prevent the proteasomal degradation of the protein kinase Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) while HSP90 contributes to the correct folding of proteins involved in DNA Homologous Repair (HR) such as RAD51 [72]. Interestingly, HSPs localized into the nucleus also contribute to cell protection from oxidative stress [73]. NRF2, together with Heat shock factor 1 (HSF1), represents the main transcription factor regulating the expression of HSP [74] and therefore NRF2 can indirectly control the DNA damage repairing pathways. To recapitulate, NRF2 activation can be induced by STAT3/SQSTM1/p62 axis and lead to the upregulation of the HSPs and thus sustain DDR. Moreover, NRF2 has been reported to directly regulate the transcription of DDR molecules such as ATM and Ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein (ATR), kinases that sense DNA damage and activate the repairing signaling cascade [75]. It is important to point out that DDR plays a key role not only in tumor prevention but also in chemoresistance of established cancer, unveiling how another process controlled by NRF2 can induce both desirable and undesirable effects, depending if it occurs in the initial or in the advanced phases of carcinogenesis. We have observed that NFR2 silencing in B lymphocytes undergoing EBV-driven transformation reduced the expression of ATM [39]. Ongoing studies in our laboratory suggest that NRF2 may contribute to sustain the expression of ATM also in B cell lymphoma cells (unpublished data). It seems that, besides through a direct transcriptional control, ATM expression may be regulated by NRF2 through the transcription of HSPs such as HSP27, of which, as said above, ATM may be a client protein [72].

HSPs could contribute to STAT3 activation mediated by NRF2, reported in previous studies [42] as, among many other molecules, HSPs may stabilize kinases such as JAK2, involved in STAT3 phosphorylation (Fig. 1b) [76]. In the interplay between NRF2 and STAT3, may play a role p53, as this onco-suppressor, activated by STAT3 inhibition [77, 78] as well as by NRF2 inhibition [79] is able, in turn, to inhibit both STAT3 [80] and NRF2 [81]. In cancer cells carrying mutp53, the mutant proteins could also act as a bridge between NRF2 and STAT3, although differently from wtp53, mutp53 may activate both transcription factors [82,83,84].

8 Conclusions

In conclusion, with this perspective, we attempted to have shed some light into the complex interplay between NRF2 and STAT3, pathways playing a key role in cancers, either of hematologic and solid origin. As these transcription factors may either activate or inhibit each other (Figs. 1 and 2) and may play opposite roles in cancer prevention while acting similarly in established cancers, their interplay is very intriguing and is worth of further investigations. A part from the cross-talk between them, NRF2 and STAT3 interplay controls a variety of processes and pathways (Fig. 3) that play a key role in cancer as well as in several other diseases. Moreover, elucidating the articulated network of NRF2, influenced by many unilateral and reciprocal interactions, recapitulated in the “NRF2-ome” [85] or that of STAT3 [86] will likely open new avenues in the prevention or treatment of cancer.

Data availability statement

The data are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- NRF2:

-

Nuclear factor E2-related factor 2

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- KEAP1:

-

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1

- AREs:

-

Antioxidant response elements

- SQSTM1:

-

Sequestosome 1

- STAT3:

-

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- JAK:

-

Janus kinase

- VEGF:

-

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

- EBV:

-

Epstein-Barr virus

- PI3K:

-

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- mTOR:

-

Mammalian target of the rapamycin

- KSHV:

-

Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C Virus

- DCs:

-

Dendritic cells

- SHP:

-

Small heterodimer protein

- SOCS3:

-

Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling 3

- PERK:

-

Protein kinase R (PKR)-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase

- UPR:

-

Unfolded Protein Response

- ER:

-

Endoplasmic Reticulum

- GSK3beta:

-

Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta

- Dnmts:

-

DNA methyltransferases

- 5-Aza:

-

5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine

- SHP-1:

-

Src homology-2 (SH2)-containing protein-tyrosine phosphatase

- DDR:

-

DNA damage response

- HSPs:

-

Heat Shock Proteins

- ATM:

-

Ataxia telangiectasia mutated

- HR:

-

Homologous Repair

- HSF1:

-

Heat shock factor 1

- ATR:

-

Ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein

References

Tonelli C, Chio IIC, Tuveson DA. Transcriptional regulation by Nrf2. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2018;29(17):1727–45. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2017.7342.

Kim J, Keum YS. NRF2, a key regulator of antioxidants with two faces towards cancer. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:2746457. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/2746457.

Furukawa M, Xiong Y. BTB protein Keap1 targets antioxidant transcription factor Nrf2 for ubiquitination by the Cullin 3-Roc1 ligase. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(1):162–71. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.25.1.162-171.2005.

Bellezza I, Giambanco I, Minelli A, Donato R. Nrf2-Keap1 signaling in oxidative and reductive stress. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2018;1865(5):721–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2018.02.010.

Katsuragi Y, Ichimura Y, Komatsu M. Regulation of the Keap1–Nrf2 pathway by p62/SQSTM1. Current Opin Toxicol. 2016;1:54–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cotox.2016.09.005.

Jiang T, Harder B, Rojo de la Vega M, Wong PK, Chapman E, Zhang DD. p62 links autophagy and Nrf2 signaling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;88(Pt B):199–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.06.014.

Hawkins WD, Grush ER, Klionsky DJ. The world’s first (and probably last) autophagy video game. Autophagy. 2023;19(1):352–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2022.2143212.

Ahuja M, Kaidery NA, Dutta D, Attucks OC, Kazakov EH, Gazaryan I, et al. Harnessing the therapeutic potential of the Nrf2/Bach1 signaling pathway in Parkinson’s disease. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11091780.

Johnson DE, O’Keefe RA, Grandis JR. Targeting the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signalling axis in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(4):234–48. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.8.

Tolomeo M, Cavalli A, Cascio A. STAT1 and Its crucial role in the control of viral infections. Int J Mol Sci. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23084095.

Verhoeven Y, Tilborghs S, Jacobs J, De Waele J, Quatannens D, Deben C, et al. The potential and controversy of targeting STAT family members in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020;60:41–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.10.002.

Lee H, Jeong AJ, Ye SK. Highlighted STAT3 as a potential drug target for cancer therapy. BMB Rep. 2019;52(7):415–23. https://doi.org/10.5483/BMBRep.2019.52.7.152.

Awasthi N, Liongue C, Ward AC. STAT proteins: a kaleidoscope of canonical and non-canonical functions in immunity and cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14(1):198. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-021-01214-y.

Tolomeo M, Cascio A. The multifaced role of STAT3 in cancer and its implication for anticancer therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22020603.

Cirone M. Cancer cells dysregulate PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway activation to ensure their survival and proliferation: mimicking them is a smart strategy of gammaherpesviruses. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2021;56(5):500–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409238.2021.1934811.

Xu J, Zhang J, Mao QF, Wu J, Wang Y. The interaction between autophagy and JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway in tumors. Front Genet. 2022;13:880359. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.880359.

Shen S, Niso-Santano M, Adjemian S, Takehara T, Malik SA, Minoux H, et al. Cytoplasmic STAT3 represses autophagy by inhibiting PKR activity. Mol Cell. 2012;48(5):667–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.013.

Dutta P, Zhang L, Zhang H, Peng Q, Montgrain PR, Wang Y, et al. Unphosphorylated STAT3 in heterochromatin formation and tumor suppression in lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):145. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-6649-2.

Huang J, Brumell JH. Bacteria-autophagy interplay: a battle for survival. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12(2):101–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro3160.

Choi Y, Bowman JW, Jung JU. Autophagy during viral infection - a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16(6):341–54. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-018-0003-6.

Granato M, Lacconi V, Peddis M, Di Renzo L, Valia S, Rivanera D, et al. Hepatitis C virus present in the sera of infected patients interferes with the autophagic process of monocytes impairing their in-vitro differentiation into dendritic cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843(7):1348–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.04.003.

Cirone M. EBV and KSHV infection dysregulates autophagy to optimize viral replication prevent immune recognition and promote tumorigenesis. Viruses. 2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/v10110599.

Granato M, Gilardini Montani MS, Zompetta C, Santarelli R, Gonnella R, Romeo MA, et al. Quercetin interrupts the positive feedback loop between STAT3 and IL-6, promotes autophagy, and reduces ROS, preventing EBV-Driven B cell immortalization. Biomolecules. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9090482.

Santarelli R, Arteni AMB, Gilardini Montani MS, Romeo MA, Gaeta A, Gonnella R, et al. KSHV dysregulates bulk macroautophagy, mitophagy and UPR to promote endothelial to mesenchymal transition and CCL2 release, key events in viral-driven sarcomagenesis. Int J Cancer. 2020;147(12):3500–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.33163.

Galluzzi L, Pietrocola F, Bravo-San Pedro JM, Amaravadi RK, Baehrecke EH, Cecconi F, et al. Autophagy in malignant transformation and cancer progression. EMBO J. 2015;34(7):856–80. https://doi.org/10.15252/embj.201490784.

Sharma V, Verma S, Seranova E, Sarkar S, Kumar D. Selective autophagy and xenophagy in infection and disease. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2018;6:147. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2018.00147.

Zhang Y, Morgan MJ, Chen K, Choksi S, Liu ZG. Induction of autophagy is essential for monocyte-macrophage differentiation. Blood. 2012;119(12):2895–905. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-08-372383.

Granato M, Santarelli R, Farina A, Gonnella R, Lotti LV, Faggioni A, et al. Epstein-barr virus blocks the autophagic flux and appropriates the autophagic machinery to enhance viral replication. J Virol. 2014;88(21):12715–26. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02199-14.

Granato M, Santarelli R, Filardi M, Gonnella R, Farina A, Torrisi MR, et al. The activation of KSHV lytic cycle blocks autophagy in PEL cells. Autophagy. 2015;11(11):1978–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2015.1091911.

Cirone M, D’Orazi G. NRF2 in cancer: cross-talk with oncogenic pathways and involvement in Gammaherpesvirus-driven carcinogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24010595.

Gilardini Montani MS, Falcinelli L, Santarelli R, Romeo MA, Granato M, Faggioni A, et al. Kaposi Sarcoma Herpes Virus (KSHV) infection inhibits macrophage formation and survival by counteracting macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF)-induced increase of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) phosphorylation and autophagy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2019;114:105560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2019.06.008.

Gilardini Montani MS, Santarelli R, Granato M, Gonnella R, Torrisi MR, Faggioni A, et al. EBV reduces autophagy, intracellular ROS and mitochondria to impair monocyte survival and differentiation. Autophagy. 2019;15(4):652–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2018.1536530.

Bendavit G, Aboulkassim T, Hilmi K, Shah S, Batist G. Nrf2 Transcription Factor Can Directly Regulate mTOR: LINKING CYTOPROTECTIVE GENE EXPRESSION TO A MAJOR METABOLIC REGULATOR THAT GENERATES REDOX ACTIVITY. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(49):25476–88. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M116.760249.

Gong H, Tai H, Huang N, Xiao P, Mo C, Wang X, et al. Nrf2-SHP cascade-mediated STAT3 inactivation contributes to AMPK-driven protection against endotoxic inflammation. Front Immunol. 2020;11:414. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.00414.

Papp D, Lenti K, Modos D, Fazekas D, Dul Z, Turei D, et al. The NRF2-related interactome and regulome contain multifunctional proteins and fine-tuned autoregulatory loops. FEBS Lett. 2012;586(13):1795–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2012.05.016.

Ju KD, Lim JW, Kim H. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma inhibits the activation of STAT3 in cerulein-stimulated pancreatic acinar cells. J Cancer Prev. 2017;22(3):189–94. https://doi.org/10.15430/JCP.2017.22.3.189.

Ahmed SM, Luo L, Namani A, Wang XJ, Tang X. Nrf2 signaling pathway: pivotal roles in inflammation. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2017;1863(2):585–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.11.005.

Greten FR, Grivennikov SI. Inflammation and cancer: triggers, mechanisms, and consequences. Immunity. 2019;51(1):27–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2019.06.025.

Gilardini Montani MS, Tarquini G, Santarelli R, Gonnella R, Romeo MA, Benedetti R, et al. p62/SQSTM1 promotes mitophagy and activates the NRF2-mediated antioxidant and anti-inflammatory response restraining EBV-driven B lymphocyte proliferation. Carcinogenesis. 2022;43(3):277–87. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgab116.

Liu H, Feng XD, Yang B, Tong RL, Lu YJ, Chen DY, et al. Dimethyl fumarate suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma progression via activating SOCS3/JAK1/STAT3 signaling pathway. Am J Transl Res. 2019;11(8):4713–25.

Gonnella R, Zarrella R, Santarelli R, Germano CA, Gilardini Montani MS, Cirone M. Mechanisms of sensitivity and resistance of primary effusion lymphoma to dimethyl fumarate (DMF). Int J Mol Sci. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23126773.

Lee JH, Rangappa S, Mohan CD, Basappa Sethi G, Lin ZX, et al. Brusatol, a Nrf2 inhibitor targets STAT3 signaling cascade in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Biomolecules. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9100550.

Tian Y, Liu H, Wang M, Wang R, Yi G, Zhang M, et al. Role of STAT3 and NRF2 in tumors: potential targets for antitumor therapy. Molecules. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27248768.

Cai SJ, Liu Y, Han S, Yang C. Brusatol, an NRF2 inhibitor for future cancer therapeutic. Cell Biosci. 2019;9:45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-019-0309-8.

Granato M, Chiozzi B, Filardi MR, Lotti LV, Di Renzo L, Faggioni A, et al. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor tyrphostin AG490 triggers both apoptosis and autophagy by reducing HSF1 and Mcl-1 in PEL cells. Cancer Lett. 2015;366(2):191–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2015.07.006.

Cirone M, Di Renzo L, Lotti LV, Conte V, Trivedi P, Santarelli R, et al. Primary effusion lymphoma cell death induced by bortezomib and AG 490 activates dendritic cells through CD91. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(3):e31732. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0031732.

Gargalionis AN, Papavassiliou KA, Papavassiliou AG. Targeting STAT3 signaling pathway in colorectal cancer. Biomedicines. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9081016.

McFarland BC, Hong SW, Rajbhandari R, Twitty GB Jr, Gray GK, Yu H, et al. NF-kappaB-induced IL-6 ensures STAT3 activation and tumor aggressiveness in glioblastoma. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e78728. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0078728.

Zhao G, Zhu G, Huang Y, Zheng W, Hua J, Yang S, et al. IL-6 mediates the signal pathway of JAK-STAT3-VEGF-C promoting growth, invasion and lymphangiogenesis in gastric cancer. Oncol Rep. 2016;35(3):1787–95. https://doi.org/10.3892/or.2016.4544.

Resemann HK, Watson CJ, Lloyd-Lewis B. The Stat3 paradox: a killer and an oncogene. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;382(1):603–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2013.06.029.

Zhang L, Badgwell DB, Bevers JJ 3rd, Schlessinger K, Murray PJ, Levy DE, et al. IL-6 signaling via the STAT3/SOCS3 pathway: functional analysis of the conserved STAT3 N-domain. Mol Cell Biochem. 2006;288(1–2):179–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-006-9137-3.

Lu C, Xu W, Shao J, Zhang F, Chen A, Zheng S. Nrf2 induces lipocyte phenotype via a SOCS3-dependent negative feedback loop on JAK2/STAT3 signaling in hepatic stellate cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2017;49:203–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2017.06.001.

Kumari N, Dwarakanath BS, Das A, Bhatt AN. Role of interleukin-6 in cancer progression and therapeutic resistance. Tumour Biol. 2016;37(9):11553–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13277-016-5098-7.

Kim SJ, Saeidi S, Cho NC, Kim SH, Lee HB, Han W, et al. Interaction of Nrf2 with dimeric STAT3 induces IL-23 expression: Implications for breast cancer progression. Cancer Lett. 2021;500:147–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2020.11.047.

Santarelli R, Gonnella R, Di Giovenale G, Cuomo L, Capobianchi A, Granato M, et al. STAT3 activation by KSHV correlates with IL-10, IL-6 and IL-23 release and an autophagic block in dendritic cells. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4241. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04241.

Wu X, Tao P, Zhou Q, Li J, Yu Z, Wang X, et al. IL-6 secreted by cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of gastric cancer via JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. Oncotarget. 2017;8(13):20741–50. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.15119.

Thongchot S, Vidoni C, Ferraresi A, Loilome W, Khuntikeo N, Sangkhamanon S, et al. Cancer-Associated fibroblast-derived IL-6 determines unfavorable prognosis in cholangiocarcinoma by affecting autophagy-associated chemoresponse. Cancers (Basel). 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13092134.

Liu T, Lv YF, Zhao JL, You QD, Jiang ZY. Regulation of Nrf2 by phosphorylation: consequences for biological function and therapeutic implications. Free Radic Biol Med. 2021;168:129–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.03.034.

Cullinan SB, Zhang D, Hannink M, Arvisais E, Kaufman RJ, Diehl JA. Nrf2 is a direct PERK substrate and effector of PERK-dependent cell survival. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(20):7198–209. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.23.20.7198-7209.2003.

Meares GP, Liu Y, Rajbhandari R, Qin H, Nozell SE, Mobley JA, et al. PERK-dependent activation of JAK1 and STAT3 contributes to endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced inflammation. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34(20):3911–25. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.00980-14.

Liu X, Li H, Liu L, Lu Y, Gao Y, Geng P, et al. Methylation of arginine by PRMT1 regulates Nrf2 transcriptional activity during the antioxidative response. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1863(8):2093–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.05.009.

McCord JM, Gao B, Hybertson BM. The complex genetic and epigenetic regulation of the Nrf2 pathways: a review. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox12020366.

Yang J, Huang J, Dasgupta M, Sears N, Miyagi M, Wang B, et al. Reversible methylation of promoter-bound STAT3 by histone-modifying enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(50):21499–504. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1016147107.

Kim E, Kim M, Woo DH, Shin Y, Shin J, Chang N, et al. Phosphorylation of EZH2 activates STAT3 signaling via STAT3 methylation and promotes tumorigenicity of glioblastoma stem-like cells. Cancer Cell. 2013;23(6):839–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2013.04.008.

Dasgupta M, Dermawan JK, Willard B, Stark GR. STAT3-driven transcription depends upon the dimethylation of K49 by EZH2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(13):3985–90. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1503152112.

Huang L, Hu B, Ni J, Wu J, Jiang W, Chen C, et al. Transcriptional repression of SOCS3 mediated by IL-6/STAT3 signaling via DNMT1 promotes pancreatic cancer growth and metastasis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35:27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-016-0301-7.

Lee H, Zhang P, Herrmann A, Yang C, Xin H, Wang Z, et al. Acetylated STAT3 is crucial for methylation of tumor-suppressor gene promoters and inhibition by resveratrol results in demethylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(20):7765–9. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1205132109.

Cao H, Wang L, Chen B, Zheng P, He Y, Ding Y, et al. DNA demethylation upregulated Nrf2 expression in Alzheimer’s disease cellular model. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:244. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2015.00244.

Taheri Z, Asadzadeh Aghdaei H, Irani S, Modarressi MH, Zahra N. Evaluation of the epigenetic demethylation of NRF2, a master transcription factor for antioxidant enzymes. Colorectal Cancer Rep Biochem Mol Biol. 2020;9(1):33–9. https://doi.org/10.29252/rbmb.9.1.33.

Zhou JW, Wang M, Sun NX, Qing Y, Yin TF, Li C, et al. Sulforaphane-induced epigenetic regulation of Nrf2 expression by DNA methyltransferase in human Caco-2 cells. Oncol Lett. 2019;18(3):2639–47. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2019.10569.

Al-Jamal HA, Mat Jusoh SA, Hassan R, Johan MF. Enhancing SHP-1 expression with 5-azacytidine may inhibit STAT3 activation and confer sensitivity in lestaurtinib (CEP-701)-resistant FLT3-ITD positive acute myeloid leukemia. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:869. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1695-x.

Sottile ML, Nadin SB. Heat shock proteins and DNA repair mechanisms: an updated overview. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2018;23(3):303–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12192-017-0843-4.

Donati YR, Slosman DO, Polla BS. Oxidative injury and the heat shock response. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990;40(12):2571–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-2952(90)90573-4.

Dayalan Naidu S, Kostov RV, Dinkova-Kostova AT. Transcription factors Hsf1 and Nrf2 engage in crosstalk for cytoprotection. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2015;36(1):6–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2014.10.011.

Khalil HS, Deeni Y. NRF2 inhibition causes repression of ATM and ATR expression leading to aberrant DNA damage response. BioDiscovery. 2015. https://doi.org/10.7750/BioDiscovery.2015.15.1.

Jego G, Hermetet F, Girodon F, Garrido C. Chaperoning STAT3/5 by heat shock proteins: interest of their targeting in cancer therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12010021.

Niu G, Wright KL, Ma Y, Wright GM, Huang M, Irby R, et al. Role of Stat3 in regulating p53 expression and function. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(17):7432–40. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.25.17.7432-7440.2005.

Granato M, Gilardini Montani MS, Santarelli R, D’Orazi G, Faggioni A, Cirone M. Apigenin, by activating p53 and inhibiting STAT3, modulates the balance between pro-apoptotic and pro-survival pathways to induce PEL cell death. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36(1):167. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-017-0632-z.

Garufi A, Baldari S, Pettinari R, Gilardini Montani MS, D’Orazi V, Pistritto G, et al. A ruthenium(II)-curcumin compound modulates NRF2 expression balancing the cancer cell death/survival outcome according to p53 status. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39(1):122. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-020-01628-5.

Lin J, Tang H, Jin X, Jia G, Hsieh JT. p53 regulates Stat3 phosphorylation and DNA binding activity in human prostate cancer cells expressing constitutively active Stat3. Oncogene. 2002;21(19):3082–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1205426.

Faraonio R, Vergara P, Di Marzo D, Pierantoni MG, Napolitano M, Russo T, et al. p53 suppresses the Nrf2-dependent transcription of antioxidant response genes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(52):39776–84. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M605707200.

Lisek K, Campaner E, Ciani Y, Walerych D, Del Sal G. Mutant p53 tunes the NRF2-dependent antioxidant response to support survival of cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2018;9(29):20508–23. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.24974.

Romeo MA, Gilardini Montani MS, Benedetti R, Santarelli R, D’Orazi G, Cirone M. STAT3 and mutp53 engage a positive feedback loop involving HSP90 and the mevalonate pathway. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1102. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.01102.

Schulz-Heddergott R, Stark N, Edmunds SJ, Li J, Conradi LC, Bohnenberger H, et al. Therapeutic ablation of gain-of-function mutant p53 in colorectal cancer inhibits Stat3-mediated tumor growth and invasion. Cancer Cell. 2018;34(2):298–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2018.07.004.

Turei D, Papp D, Fazekas D, Foldvari-Nagy L, Modos D, Lenti K, et al. NRF2-ome: an integrated web resource to discover protein interaction and regulatory networks of NRF2. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:737591. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/737591.

Laudisi F, Cherubini F, Monteleone G, Stolfi C. STAT3 interactors as potential therapeutic targets for cancer treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19061787.

Funding

This work was supported by AIRC (IG 2019-23040).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A, M.A.R.,R.B., M.S.G.M.,R.S, R.G., G.D.O., M.C. wrote the MS and prepared the figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arena, A., Romeo, M.A., Benedetti, R. et al. NRF2 and STAT3: friends or foes in carcinogenesis?. Discov Onc 14, 37 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12672-023-00644-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12672-023-00644-z