Abstract

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic gastrointestinal (GI) disorder that reportedly affects 5% to 20% of the world population. The etiology of IBS is not completely understood, but diet appears to play an important role in its pathophysiology. Asian diets differ considerably from those in Western countries, which might explain differences in the prevalence, sex, and clinical presentation seen between patients with IBS in Asian and Western countries. Dietary regimes such as a low-fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP) diet and the modified National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) diet improve both symptoms and the quality of life in a considerable proportion of IBS patients. It has been speculated that diet is a prebiotic for the intestinal microbiota and favors the growth of certain bacteria. These bacteria ferment the dietary components, and the products of fermentation act upon intestinal stem cells to influence their differentiation into enteroendocrine cells. The resulting low density of enteroendocrine cells accompanied by low levels of certain hormones gives rise to intestinal dysmotility, visceral hypersensitivity, and abnormal secretion. This hypothesis is supported by the finding that changing to a low-FODMAP diet restores the density of GI cells to the levels in healthy subjects. These changes in gut endocrine cells caused by low-FODMAP diet are also accompanied by improvements in symptoms and the quality of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic functional disorder. Although the etiology of IBS is unknown, several factors seem to play a role in its pathophysiology; these include genetic factors, diet, intestinal microbiota, low-grade inflammation, and abnormalities of the gastrointestinal (GI) endocrine cells [1].

IBS patients suffer from intermittent lower abdominal pain, altered bowel habits, and abdominal bloating/distension [2]. IBS is mainly diagnosed based on an assessment of the symptoms described by the Rome criteria [3]. Based on the stool pattern, IBS patients are divided into four subtypes: diarrhea-predominant, constipation-predominant, mixed diarrhea and constipation, and unclassified [4, 5]. IBS patients are further divided into two subsets: sporadic (non-specific) and post-infection [6]. Sporadic IBS includes patients who have had symptoms that are not associated with GI infections. Post-infection IBS occurs in otherwise healthy subjects as the sudden onset of IBS symptoms after an episode of gastroenteritis [6], and reportedly constitutes 6% to 17% of patients with IBS [7].

IBS patients visit physicians more often than patients with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or asthma; 12% to 14% of primary care visits and 28% of gastroenterologist referral are due to IBS [8,9,10]. The onset of IBS is usually in young age (< 45 years) during the most active phase of their lives [11, 12]. There is a sex difference in the prevalence of IBS, with a female:male ratio of 2:1 [11]. IBS reduces the quality of life to the same degree as other chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus and kidney failure [13].

The present review discusses the role of diet in the pathophysiology of IBS, the use of diet in its management, and the possible mechanisms behind the effects of diet on IBS.

Role of diet in IBS

IBS patients associate their symptom with food intake, especially specific food items such as wheat products, milk and its products, cabbage, onion, hot spices, and fried and smoked foodstuffs [14, 15]. Despite IBS patients avoiding certain food items, diet surveys have not found any differences in intake between IBS patients and community controls [16]. Furthermore, there is no difference between IBS patients and the background population in the intake of calories, carbohydrates, proteins, or fats [15]. However, the diets of IBS patients tend to be low in calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, vitamin B2, and vitamin A [15].

While the prevalence of IBS in Asia is 5% to 9% [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28], it is 10% to 20% in Western countries (USA and Europe) [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Furthermore, no female predominance was found in Asian IBS patients [2], in contrast toWestern IBS patients [22,23,24,25]. The clinical presentation of IBS differs between Asian and Western patients. Abdominal bloating is a more-common complaint than pain in Asians, and this abdominal pain is localized to the upper abdomen rather than in the lower abdomen in Asian patients. Moreover, alteration in bowel habits is much less prominent in Asian IBS patients than in their Western counterparts [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

The Western diet is rich in fats and beef protein and low in carbohydrates and fiber, whereas the Asian diet is rich in carbohydrates and fiber, and low in fats and meat protein [29]. Asian meals consist mainly of rice, vegetables, fish, eggs, poultry, pork, vegetable oil, and spices [29]. Rice is absorbed in the small intestine and produces negligible amounts of intestinal gas [29]. Furthermore, cellophane noodles made from mung bean flour, a traditional Asian food, produce much less intestinal gas than do wheat noodles [30]. These main differences between the diet in Asia and Western countries might at least partially explain the differences mentioned above between patients with IBS in Asian and Western countries, including in its prevalence, sex difference, and clinical presentation.

Diet in the management of IBS

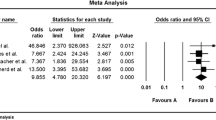

The intake of a low-fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP) diet reportedly improves both symptoms and the quality of life in 50% to 76% of IBS patients (Table 1) [16, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. Two recent systematic reviews of randomized trials produced significant evidence for the short-term benefits of a low-FODMAP diet on GI symptoms and quality of life in patients with IBS [39, 40]. However, the studies included in these reviews were of low quality, due to methodological heterogeneity and a high risk of bias, which commonly occurs in studies of dietary treatments. However, a low-FODMAP diet requires intensive meal-planning, is expensive and difficult to maintain over a long period, and can result in negative changes in the intestinal microbiota [35, 41,42,43]. Furthermore, consuming a low-FODMAP diet for a long time may result in deficiencies in vitamins, minerals, and naturally occurring antioxidants [42, 43]. The benefits of low-FODMAP diet have been demonstrated in all IBS subtypes, but IBS symptoms were found to improve less in patients with constipation-predominant IBS in two studies [36, 44].

The modified National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) diet has the same effect as a low-FODMAP diet in around half (46% to 54%) of IBS patients, but it is easy to maintain and does not have the hazards seen with a low-FODMAP diet [35, 36]. The modified NICE diet is the first diet recommended for IBS patients by the British Dietetic Association [15, 16, 45, 46]. In the modified NICE diet, patients are advised to consume regular meals; to replace wheat products with spelt products; to reduce the intakes of fatty food, onions, cabbage, and beans; to avoid carbonated beverages, and sweeteners whose names end with “-ol”; and to regularly consume psyllium husk fibers. The British Dietetic Association also recommends reducing the intakes of coffee, spicy foods, and alcohol [15, 16].

Role of diet in the pathophysiology of IBS

Diet induces IBS symptoms via several mechanisms, including intestinal distention, direct chemical stimulation of the epithelial cells lining the intestinal lumen, and altered intestinal microbiota. There is no evidence that IBS patients suffer from a food allergy mediated by immunoglobulin E [47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55]. It has also been documented that food intolerance does not occur in IBS, which is a non-toxic, non-immune-mediated reaction to bioactive chemicals in food [2, 55].

The intestine can be distended by the amount/volume of ingested food, fluid secretion induced by ingested food, and gas production caused by intestinal bacteria fermenting food. GI wall distention is well known to induce symptoms of fullness, distention, and abdominal pain [56]. Early symptoms can also develop as a direct effect of food components such as chili, since this contains capsaicin that induces abdominal burning and pain [57]. The modulation of GI motility and sensation via neurohormonal mechanisms such as fatty food was found to induce gut hypersensitivity and delay the GI transit of gas and the contents [14, 58]. There are several possible mechanisms by which a FODMAP-containing diet can trigger IBS symptoms (Fig. 1), such as by increasing the osmotic pressure in the large intestine, acting as prebiotics for gas-producing Clostridium bacteria, providing a substrate for bacterial fermentation causing abdominal distension and pain/discomfort, and interacting with the enteroendocrine cells that regulate GI sensation, motility, secretion, and absorption.

Schematic illustration of the possible mechanisms by which fermentable oligo- di- monosaccharide and polyol (FODMAP) can trigger IBS symptoms. Upon reaching the large intestine, FODMAP increases the osmotic pressure and act as prebiotics for gas-producing Clostridium bacteria, inducing an increase in gas production. The production of gas increases the luminal pressure and stimulates the release of serotonin from enterochromaffin (EC) cells. Serotonin acts on the intrinsic sensory nerve fibers (ISNF) of the submucosal and myenteric ganglia, which in turn convey the activation via the extrinsic sensory nerve fibers (ESNF) to the central nervous system. They also act indirectly on the enteroendocrine cells that regulate gastrointestinal sensation, motility, secretion, and absorption. Reproduced from El-Salhy and Gundersen [31] with permission from the authors and publisher

A small proportion of IBS patients may have undiagnosed celiac disease and may develop GI symptoms after ingesting foodstuffs that contain wheat or gluten. A meta-analysis suggested that the prevalence of biopsy-demonstrated celiac disease in cases meeting diagnostic criteria for IBS was 4%, which was fourfold higher than that in controls without IBS [59]. Celiac disease was diagnosed by serology and biopsy in 1% of Chinese patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS according to the Rome-III criteria [60].

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS; better termed non-celiac wheat sensitivity) is defined as having GI and extra-GI IBS-like symptoms without celiac disease or wheat allergy, but the symptoms are relieved by a gluten-free diet (GFD) and relapse upon a gluten challenge [61,62,63,64,65,66]. The prevalence of NCGS has been reported as 0.55% to 6% of the US population [63, 67]. A randomized, double-blind, cross-over, food challenge study using gluten protein and control protein in IBS patients who were already consuming a low-FODMAP diet demonstrated that gluten protein produced symptoms similar to whey protein (as a control) [68]. Furthermore, 24% of those who believed that they had NCGS experienced uncontrolled symptoms despite consuming a GFD [69]. This suggests that the aggravation of GI symptoms in IBS patients who consume a gluten diet is the result of the carbohydrate content (fructans and galactans) of wheat rather than gluten.

As mentioned above, diet, the intestinal bacterial flora, and abnormalities of the GI endocrine cells play an important role in the pathophysiology of IBS [1, 70,71,72]. Moreover, these factors seem to interact with each other [13].

The enteroendocrine cells are scattered between the epithelial cells facing the gut lumen [6, 73]. The enteroendocrine cells have sensors in the form of microvilli protruding into the lumen, and these sense the gut contents (mostly nutrients) and respond to them by releasing hormones into the lamina propria (Fig. 2) [74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86]. The hormones released from the enteroendocrine cells vary with the gut intraluminal contents and the proportions of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats [6, 73]. These released hormones regulate visceral sensation, motility, secretion, absorption, the local immune defense system, cell proliferation, and appetite [2, 73, 87,88,89]. Patients with IBS exhibit gut dysmotility, visceral hypersensitivity, and abnormal secretion [90]. The densities of enteroendocrine cells are generally lower in IBS patients than in healthy subjects [91], and these abnormalities appear to play a major role in the pathophysiology of IBS [90, 92]. It is particularly interesting that the density of enteroendocrine cells in the intestine did not differ between Thai IBS patients and healthy controls, nor did the densities of stem cells or progenitors for enteroendocrine cells [93, 94].

The gut endocrine cells have specialized microvilli that project into the lumen and act as sensors for the luminal contents (mostly for nutrients). These respond to the luminal contents by releasing hormones into the lamina propria. These hormones act locally on the nearby structures (paracrine mode of action) or enter the bloodstream and act on distant structures (endocrine mode of action). Reproduced from El-Salhy et al. [13] with permission from the authors and publisher

It is hypothesized that diet as a prebiotic can favor the growth of certain bacteria. The fermentation products of such a diet produced by these bacteria act on intestinal stem cells to cause a low differentiation into endocrine cells. The resulting low density of enteroendocrine cells and the subsequent low levels of certain hormones give rise to intestinal dysmotility, visceral hypersensitivity, and abnormal secretion (Fig. 3) [13].

Schematic illustration of the possible role of interactions between diet, gut microbiota, and gut endocrine cells in the pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). The diet that we consume acts as a prebiotic that favors the growth of certain types of bacteria. These bacteria can in turn ferment the diet, resulting in by-products that may act on the stem cells in a way that reduces their number. This in turn would result in a low density of gut endocrine cells, which gives rise to the gut dysmotility, visceral hypersensitivity, and abnormal gut secretion seen in IBS patients. Reproduced from El-Salhy et al. [13] with permission from the authors and publisher

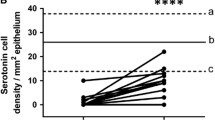

This hypothesis is supported by the finding that changing from the common Norwegian diet of IBS patients to a low-FODMAP diet restored the density of GI cells to the levels in healthy subjects (Figs. 4 and 5) [unpublished data, 95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,102]. In addition, Thai IBS patients consuming different favorable diets for IBS did not show abnormalities in the enteroendocrine cells [93, 94]. Moreover, fecal microbiota transplantation changes the densities of intestinal endocrine cells in patients with IBS towards those seen in healthy subjects [103]. These changes in gut endocrine cells caused by a low-FODMAP diet and fecal microbiota transplantation were accompanied by improvements in symptoms and the quality of life [99].

Peptide YY (PYY) cells in the colon of a healthy control (a), in a patient with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (b), and in a patient with IBS after 3 months on a low-FODMAP diet (c). PYY regulates the intestinal motility, which is a major mediator of the ilial break, as well as the absorption of water and electrolytes in the colon

Conclusion

Diet plays an important role in the pathophysiology of IBS by interacting with other factors that affect the pathophysiology, namely the intestinal bacterial flora and enteroendocrine cells. Differences between Asian and Western diets may account for the differences between patients with IBS in Asia and Western countries, including in the prevalence, sex, and clinical presentation.

References

El-Salhy M. Recent developments in the pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:7621–36.

El-Salhy M. Irritable bowel syndrome: diagnosis and pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5151–63.

El-Salhy M, Gilja OH, Hatlebakk JG. Overlapping of irritable bowel syndrome with erosive esophagitis and the performance of Rome criteria in diagnosing IBS in a clinical setting. Mol Med Rep. 2019;20:787–94.

Simren M, Palsson OS, Whitehead WE. Update on Rome IV criteria for colorectal disorders: implications for clinical practice. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017;19:15–23.

Schmulson MJ, Drossman DA. What is new in Rome IV. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23:151–63.

El-Salhy M, Gundersen D, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Diagnosis, Pathogenesis and Treatment Options. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc.; 2012.

Longstreth GF, Hawkey CJ, Mayer EA, et al. Characteristics of patients with irritable bowel syndrome recruited from three sources: implications for clinical trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:959–64.

Talley NJ, Gabriel SE, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Evans RW. Medical costs in community subjects with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1736–41.

Jones R, Lydeard S. Irritable bowel syndrome in the general population. BMJ. 1992;304:87–90.

Hungin AP, Whorwell PJ, Tack J, Mearin F. The prevalence, patterns and impact of irritable bowel syndrome: an international survey of 40,000 subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:643–50.

Grundmann O, Yoon SL. Irritable bowel syndrome: epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment: an update for health-care practitioners. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:691–9.

El-Salhy M. FMT in IBS: how cautious should we be? Gut. 2021;70:626–8.

El-Salhy M, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. Diet in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): interaction with gut microbiota and gut hormones. Nutrients. 2019;11:1824–39.

Simren M, Mansson A, Langkilde AM, et al. Food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in the irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion. 2001;63:108–15.

Ostgaard H, Hausken T, Gundersen D, El-Salhy M. Diet and effects of diet management on quality of life and symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Rep. 2012;5:1382–90.

El-Salhy M, Ostgaard H, Gundersen D, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. The role of diet in the pathogenesis and management of irritable bowel syndrome (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2012;29:723–31.

Gwee KA, Lu CL, Ghoshal UC. Epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome in Asia: something old, something new, something borrowed. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1601–7.

Hoseini-Asl MK, Amra B. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in Shahrekord, Iran. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2003;22:215–6.

Shah SS, Bhatia SJ, Mistry FP. Epidemiology of dyspepsia in the general population in Mumbai. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2001;20:103–6.

Ghoshal UC, Abraham P, Bhatt C, et al. Epidemiological and clinical profile of irritable bowel syndrome in India: report of the Indian Society of Gastroenterology Task Force. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2008;27:22–8.

Han SH, Lee OY, Bae SC, et al. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in Korea: population-based survey using the Rome II criteria. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1687–92.

Kwan AC, Hu WH, Chan YK, Yeung YW, Lai TS, Yuen H. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in Hong Kong. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:1180–6.

Husain N, Chaudhry IB, Jafri F, Niaz SK, Tomenson B, Creed F. A population-based study of irritable bowel syndrome in a non-Western population. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:1022–9.

Xiong LS, Chen MH, Chen HX, Xu AG, Wang WA, Hu PJ. A population-based epidemiologic study of irritable bowel syndrome in South China: stratified randomized study by cluster sampling. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:1217–24.

Chang FY, Lu CL, Chen TS. The current prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in Asia. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;16:389–400.

Karaman N, Turkay C, Yonem O. Irritable bowel syndrome prevalence in city center of Sivas. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2003;14:128–31.

Celebi S, Acik Y, Deveci SE, et al. Epidemiological features of irritable bowel syndrome in a Turkish urban society. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:738–43.

Masud MA, Hasan M, Khan AK. Irritable bowel syndrome in a rural community in Bangladesh: prevalence, symptoms pattern, and health care seeking behavior. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1547–52.

Gonlachanvit S. Are rice and spicy diet good for functional gastrointestinal disorders? J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;16:131–8.

Linlawan S, Patcharatrakul T, Somlaw N, Gonlachanvit S. Effect of rice, wheat, and mung bean ingestion on intestinal gas production and postprandial gastrointestinal symptoms in non-constipation irritable bowel syndrome patients. Nutrients. 2019;11:2061.

El-Salhy M, Gundersen D. Diet in irritable bowel syndrome. Nutr J. 2015;14:36.

El-Salhy M, Gundersen D, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. Diet and irritable bowel syndrome, with a focus on appetite-regulating hormones. In: Watson RR, editor. Nutrition in the Prevention and Treatment of Abdominal Obesity. San Diego: Elsevier; 2014. p. 5–16.

El-Salhy M. Diet in the pathophysiology and management of irritable bowel syndrome. Cleve Clin J Med. 2016;83:663–4.

Staudacher HM, Whelan K, Irving PM, Lomer MC. Comparison of symptom response following advice for a diet low in fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPs) versus standard dietary advice in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24:487–95.

Eswaran SL, Chey WD, Han-Markey T, Ball S, Jackson K. A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing the Low FODMAP Diet vs. Modified NICE Guidelines in US Adults with IBS-D. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1824–32.

Bohn L, Storsrud S, Liljebo T, et al. Diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome as well as traditional dietary advice: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1399–407.

Patcharatrakul T, Juntrapirat A, Lakananurak N, Gonlachanvit S. Effect of Structural Individual Low-FODMAP Dietary Advice vs. Brief Advice on a Commonly Recommended Diet on IBS Symptoms and Intestinal Gas Production. Nutrients. 2019;11:2856.

Zahedi MJ, Behrouz V, Azimi M. Low fermentable oligo-di-mono-saccharides and polyols diet versus general dietary advice in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33:1192–9.

Schumann D, Klose P, Lauche R, Dobos G, Langhorst J, Cramer H. Low fermentable, oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyol diet in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition. 2018;45:24–31.

Dionne J, Ford AC, Yuan Y, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the efficacy of a gluten-free diet and a low FODMAPs diet in treating symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:1290–300.

Halmos EP, Christophersen CT, Bird AR, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. Diets that differ in their FODMAP content alter the colonic luminal microenvironment. Gut. 2015;64:93–100.

Catassi G, Lionetti E, Gatti S, Catassi C. The Low FODMAP Diet: Many Question Marks for a Catchy Acronym. Nutrients. 2017;9:292.

Staudacher HM, Whelan K. The low FODMAP diet: recent advances in understanding its mechanisms and efficacy in IBS. Gut. 2017;66:1517–27.

Pedersen N, Andersen NN, Végh Z, et al. Ehealth: low FODMAP diet vs Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16215–26.

McKenzie YA, Alder A, Anderson W, et al. British Dietetic Association evidence-based guidelines for the dietary management of irritable bowel syndrome in adults. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2012;25:260–74.

McKenzie YA, Thompson J, Gulia P, Lomer MC. British Dietetic Association systematic review of systematic reviews and evidence-based practice guidelines for the use of probiotics in the management of irritable bowel syndrome in adults (2016 update). J Hum Nutr Diet. 2016;29:576–92.

Whorwell PJ. The growing case for an immunological component to irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:805–7.

Zar S, Benson MJ, Kumar D. Food-specific serum IgG4 and IgE titers to common food antigens in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1550–7.

Zar S, Kumar D, Benson MJ. Food hypersensitivity and irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:439–49.

Park MI, Camilleri M. Is there a role of food allergy in irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia? A systematic review. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18:595–607.

Uz E, Turkay C, Aytac S, Bavbek N. Risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome in Turkish population: role of food allergy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:380–3.

Dainese R, Galliani EA, De Lazzari F, Di Leo V, Naccarato R. Discrepancies between reported food intolerance and sensitization test findings in irritable bowel syndrome patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1892–7.

Bischoff S, Crowe SE. Gastrointestinal food allergy: new insights into pathophysiology and clinical perspectives. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1089–113.

McKee AM, Prior A, Whorwell PJ. Exclusion diets in irritable bowel syndrome: are they worthwhile? J Clin Gastroenterol. 1987;9:526–8.

Boettcher E, Crowe SE. Dietary proteins and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:728–36.

Distrutti E, Azpiroz F, Soldevilla A, Malagelada JR. Gastric wall tension determines perception of gastric distention. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1035–42.

Gonlachanvit S, Mahayosnond A, Kullavanijaya P. Effects of chili on postprandial gastrointestinal symptoms in diarrhoea predominant irritable bowel syndrome: evidence for capsaicin-sensitive visceral nociception hypersensitivity. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:23–32.

Serra J, Salvioli B, Azpiroz F, Malagelada JR. Lipid-induced intestinal gas retention in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:700–6.

Ford AC, Chey WD, Talley NJ, Malhotra A, Spiegel BM, Moayyedi P. Yield of diagnostic tests for celiac disease in individuals with symptoms suggestive of irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:651–8.

Wang H, Zhou G, Luo L, et al. Serological screening for celiac disease in adult Chinese patients with diarrhea predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e1779.

Lundin KE. Non-celiac gluten sensitivity - why worry? BMC Med. 2014;12:86.

Aziz I, Sanders DS. Emerging concepts: from coeliac disease to non-coeliac gluten sensitivity. Proc Nutr Soc. 2012;71:576–80.

Mansueto P, Seidita A, D’Alcamo A, Carroccio A. Non-celiac gluten sensitivity: literature review. J Am Coll Nutr. 2014;33:39–54.

Volta U, Tovoli F, Cicola R, et al. Serological tests in gluten sensitivity (nonceliac gluten intolerance). J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:680–5.

Sapone A, Lammers KM, Mazzarella G, et al. Differential mucosal IL-17 expression in two gliadin-induced disorders: gluten sensitivity and the autoimmune enteropathy celiac disease. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2010;152:75–80.

El-Salhy M, Hatlebakk JG, Gilja OH, Hausken T. The relation between celiac disease, nonceliac gluten sensitivity and irritable bowel syndrome. Nutr J. 2015;14:92.

Piston F, Gil-Humanes J, Barro F. Integration of promoters, inverted repeat sequences and proteomic data into a model for high silencing efficiency of coeliac disease related gliadins in bread wheat. BMC Plant Biol. 2013;13:136.

Biesiekierski JR, Peters SL, Newnham ED, Rosella O, Muir JG, Gibson PR. No effects of gluten in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity after dietary reduction of fermentable, poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:320–8.e1–3.

Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Shepherd SJ, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Characterization of adults with a self-diagnosis of nonceliac gluten sensitivity. Nutr Clin Pract. 2014;29:504–9.

Ghoshal UC, Park H, Gwee KA. Bugs and irritable bowel syndrome: the good, the bad and the ugly. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:244–51.

Ghoshal UC, Shukla R, Ghoshal U, Gwee KA, Ng SC, Quigley EM. The gut microbiota and irritable bowel syndrome: friend or foe? Int J Inflam. 2012;2012:151085.

El-Salhy M, Hatlebakk JG, Gilja OH, Bråthen Kristoffersen A, Hausken T. Efficacy of faecal microbiota transplantation for patients with irritable bowel syndrome in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Gut. 2020;69:859–67.

El-Salhy M, Seim I, Chopin L, Gundersen D, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. Irritable bowel syndrome: the role of gut neuroendocrine peptides. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2012;4:2783–800.

Sandstrom O, El-Salhy M. Ageing and endocrine cells of human duodenum. Mech Ageing Dev. 1999;108:39–48.

El-Salhy M. Ghrelin in gastrointestinal diseases and disorders: a possible role in the pathophysiology and clinical implications (review). Int J Mol Med. 2009;24:727–32.

Tolhurst G, Reimann F, Gribble FM. Intestinal sensing of nutrients. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2012; 209:309–35.

Lee J, Cummings BP, Martin E, et al. Glucose sensing by gut endocrine cells and activation of the vagal afferent pathway is impaired in a rodent model of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Phys Regul Integr Comp Phys. 2012;302:R657–66.

Parker HE, Reimann F, Gribble FM. Molecular mechanisms underlying nutrient-stimulated incretin secretion. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2010;12:e1.

Raybould HE. Nutrient sensing in the gastrointestinal tract: possible role for nutrient transporters. J Physiol Biochem. 2008;64:349–56.

San Gabriel A, Nakamura E, Uneyama H, Torii K. Taste, visceral information and exocrine reflexes with glutamate through umami receptors. J Med Investig. 2009;56 Suppl:209–17.

Rudholm T, Wallin B, Theodorsson E, Näslund E, Hellström PM. Release of regulatory gut peptides somatostatin, neurotensin and vasoactive intestinal peptide by acid and hyperosmolal solutions in the intestine in conscious rats. Regul Pept. 2009;152:8-12.

Sternini C, Anselmi L, Rozengurt E. Enteroendocrine cells: a site of ‘taste’ in gastrointestinal chemosensing. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2008;15:73–8.

Sternini C. Taste receptors in the gastrointestinal tract. IV. Functional implications of bitter taste receptors in gastrointestinal chemosensing. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G457–61.

Buchan AM. Nutrient tasting and signaling mechanisms in the gut III. Endocrine cell recognition of luminal nutrients. Am J Phys. 1999;277:G1103–7.

Montero-Hadjadje M, Elias S, Chevalier L, et al. Chromogranin A promotes peptide hormone sorting to mobile granules in constitutively and regulated secreting cells: role of conserved N- and C-terminal peptides. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:12420–31.

Shooshtarizadeh P, Zhang D, Chich JF, et al. The antimicrobial peptides derived from chromogranin/secretogranin family, new actors of innate immunity. Regul Pept. 2010;165:102–10.

May CL, Kaestner KH. Gut endocrine cell development. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;323:70–5.

Gunawardene AR, Corfe BM, Staton CA. Classification and functions of enteroendocrine cells of the lower gastrointestinal tract. Int J Exp Pathol. 2011;92:219–31.

Seim I, El-Salhy M, Hausken T, Gundersen D, Chopin L. Ghrelin and the brain-gut axis as a pharmacological target for appetite control. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:768–75.

El-Salhy M, Gundersen D, Gilja OH, Hatlebakk JG. Hausken T. Is irritable bowel syndrome an organic disorder? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:384–400.

El-Salhy M. Possible role of intestinal stem cells in the pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:1427–38.

El-Salhy M, Hausken T, Gilja OH, Hatlebakk JG. The possible role of gastrointestinal endocrine cells in the pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;11:139–48.

El-Salhy M, Patcharatrakul T, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T, Gilja OH, Gonlachanvit S. Chromogranin A cell density in the large intestine of Asian and European patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:691-7.

El-Salhy M, Patcharatrakul T, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T, Gilja OH, Gonlachanvit S. Enteroendocrine, Musashi 1 and neurogenin 3 cells in the large intestine of Thai and Norwegian patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:1331–9.

Mazzawi T, El-Salhy M. Changes in small intestinal chromogranin A-immunoreactive cell densities in patients with irritable bowel syndrome after receiving dietary guidance. Int J Mol Med. 2016;37:1247–53.

Mazzawi T, El-Salhy M. Dietary guidance and ileal enteroendocrine cells in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Exper Ther Med. 2016;12:1398–404.

Mazzawi T, Gundersen D, Hausken T, El-Salhy M. Increased gastric chromogranin A cell density following changes to diets of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Rep. 2014;10:2322–6.

Mazzawi T, Gundersen D, Hausken T, El-Salhy M. Increased chromogranin A cell density in the large intestine of patients with irritable bowel syndrome after receiving dietary guidance. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;823897.

Mazzawi T, Hausken T, Gundersen D, El-Salhy M. Effects of dietary guidance on the symptoms, quality of life and habitual dietary intake of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Rep. 2013;8:845–52.

Mazzawi T, Hausken T, Gundersen D, El-Salhy M. Effect of dietary management on the gastric endocrine cells in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69:519–24.

Mazzawi T, Hausken T, Gundersen D, El-Salhy M. Dietary guidance normalizes large intestinal endocrine cell densities in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:175–81.

Mazzawi T, Lied GA, El-Sahy M, et al. Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on the symptoms and duodenal enteroendocrine cells in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. United European Gastroenterol J. 2016;4 Suppl. 5:677.

El-Salhy M, Johansen PH, Mazzawi T, et al. Effect of faecal microbiota transplantation on the enteroendocrine cells of the colon in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): double blinded-placebo controlled study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29:71.

Acknowledgments

The studies by the authors cited in this review are supported by a grant from Helse Fonna (grant no. 40415).

Funding

Open Access funding provided by University of Bergen (incl Haukeland University Hospital).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

ME-S, TP, and SG declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The authors are solely responsible for the data and the contents of the paper. In no way, the Honorary Editor-in-Chief, Editorial Board Members, the Indian Society of Gastroenterology or the printer/publishers are responsible for the results/findings and content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

El-Salhy, M., Patcharatrakul, T. & Gonlachanvit, S. The role of diet in the pathophysiology and management of irritable bowel syndrome. Indian J Gastroenterol 40, 111–119 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12664-020-01144-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12664-020-01144-6