Abstract

Wheat products make a substantial contribution to the dietary intake of many people worldwide. Despite the many beneficial aspects of consuming wheat products, it is also responsible for several diseases such as celiac disease (CD), wheat allergy, and nonceliac gluten sensitivity (NCGS). CD and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients have similar gastrointestinal symptoms, which can result in CD patients being misdiagnosed as having IBS. Therefore, CD should be excluded in IBS patients. A considerable proportion of CD patients suffer from IBS symptoms despite adherence to a gluten-free diet (GFD). The inflammation caused by gluten intake may not completely subside in some CD patients. It is not clear that gluten triggers the symptoms in NCGS, but there is compelling evidence that carbohydrates (fructans and galactans) in wheat does. It is likely that NCGS patients are a group of self-diagnosed IBS patients who self-treat by adhering to a GFD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The three most important food grains worldwide are wheat, maize, and rice [1]. However, the ability to produce high yields of wheat under a broad range of conditions, so that it can be cultivated successfully at global latitudes from 67° N in Scandinavia to 45° S in Argentina, renders it particularly useful as a food source [1]. The nutritional needs following the two world wars and the exponential growth of the world population resulted in the global production and consumption of wheat expanding hugely by the end of the twentieth century [1–3]. Moreover, several countries in Asia have reduced their consumption of rice considerably during the last years, probably in favor of wheat consumption [4] [Hossain M. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation. 2004. www.fao.org/rice2004/en/e-001.htm] (Table 1). The high consumption of wheat is not only attributed to its adaptability and potential for high yields, but also to its viscoelasticity, which allows it to be processed into several food items such as bread, baked products, and pastas [1]. Wheat and wheat-based products make substantial contributions to the dietary intake of protein, dietary fiber, minerals (especially iron, zinc, and selenium), vitamins, phytochemicals, and energy [1]. It has been estimated that several billion people rely on wheat for a substantial part of their diet [1].

White flour comprises about 80 % starch and 10 % protein [1, 5]. The indigestible oligosaccharides such as fructo-oligosaccharides and fructans constitute 13.4 % of the dietary fiber in wheat [5, 6]. Moreover, wheat contains a considerable amount of the indigestible oligosaccharides galactans [6, 7]. Gluten constitutes 80 % of the wheat proteins, and comprises two major groups: the glutenins and the gliadins (prolines) [8, 9]. The glutenins occur in two forms, the high- and low-molecular-weight fractions [8–11], while the gliadins exist as three structural forms, α-, ω-, and γ-gliadins [8–11]. Glutenins and gliadins undergo partial digestion in the upper gastrointestinal tract, resulting in the formation of various native peptide derivatives that are resistant to digestion by the gastrointestinal proteases [12].

Despite the many beneficial aspects of consuming wheat products, it can cause several diseases such as celiac disease (CD), wheat allergy (WA), and nonceliac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) [12, 13]. The prevalence rates of CD, WA, and NCGS are estimated to be 0.5–2 % in the Western population [14–23], 0.2–0.5 % in the European population [24], and 0.55–6 % of the USA population [11, 25], respectively. CD is an immunological response to ingested gluten that results in small-intestine villous atrophy with increased intestinal permeability and malabsorption of nutrients [26]; WA is characterized by an IgE-mediated response against various wheat components that results in respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms [27]; and NCGS is characterized by both gastrointestinal and extragastrointestinal symptoms that are triggered by the ingestion of wheat products (possibly due to the gluten content). These symptoms improve after removing wheat products from the diet, and relapse following a wheat challenge. The gastrointestinal symptoms in NCGS are abdominal pain, diarrhea or constipation, nausea, and vomiting, and the extragastrointestinal symptoms are headache, musculoskeletal pain, brain fog, fatigue, and depression [28, 29]. NCGS is often perceived by the patients themselves, leading to self-diagnosis and self-treatment.

Patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), CD, and the recently debated diagnosis of NCGS exhibit similar gastrointestinal and extragastrointestinal symptoms [4, 30–37]. Application of symptom-based diagnosis criteria such as the Rome III criteria could result in diagnosing patients with CD or NCGS as having IBS. However, it has been suggested that these three conditions overlap [4, 12]. The aim of this review was to elucidate this possible overlapping of these three conditions and to find out a way to separate them in everyday clinical practice.

IBS and CD

The connection between IBS and CD: is it a misdiagnosis or an overlap?

As mentioned above, there is overlap in the symptoms of IBS and CD. Since the diagnosis of IBS is based mainly on symptom assessment using symptom criteria such as the Rome III criteria, there is a risk of CD patients being misdiagnosed as having IBS. The situation is complicated even further by the fact that the abdominal symptoms in both IBS and CD patients are triggered by the ingestion of wheat products. However, whereas this is caused by gluten allergy in CD patients, it is attributed in IBS patients to the long-sugar-polymer fructans in wheat [38]. The prevalence of CD patients among IBS patients who have been misdiagnosed using symptom criteria for IBS has varied between studies from 0 to 31.8 %, but in most studies it seems to lie in the range 0.4–4.7 % [14, 23, 39–48]. Regardless of this variation in the prevalence of CD patients who have been misdiagnosed with IBS between studies, it is a considerable number that should not be disregarded. These findings have led to the British Society of Gastroenterology recommending that CD should be excluded in all patients referred with IBS [49], and the American College of Gastroenterology have advised the exclusion of CD in patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS and IBS with a mixed bowel pattern [47]. Based on the international guidelines, published data, and our own clinical experience, we believe that all referred IBS patients should be tested for CD with serologic testing, including a combination of tissue transglutaminase (tTG) and deamidated gliadin peptide (DGP) antibodies, which have demonstrated a high sensitivity and specificity [50], and when there is doubt, duodenal biopsy samples should be taken. In our clinical experience, it is not uncommon for patients to test positive for tTG but negative for DGP, and vice versa, making it necessary to perform both tests in patients. This suggestion is supported by reports that the time between CD symptom onset and correct medical diagnosis is between 5.1 and 11.7 years [51, 52]. This period is prolonged from an average of 7 years in CD patients with no prodromal IBS to 10 years in those with prodromal IBS [53].

The reported prevalence of positivity to antigliadin antibodies (AGA; IgG and IgA) without any confirmation of positivity to tTG or DGP antibodies in the blood of IBS patients has varied from 5 to 17 % [14, 44, 54] to as high as about 50 % [55, 56]. AGA positivity has been reported to have a good sensitivity, but a low specificity for CD [57], and the serum of 12–15 % of healthy subjects is positive for AGA [14, 44, 57, 58]. This raises an interesting question: why would a healthy subject have these antibodies to gliadin with no clinical implications? One could speculate that mucosal damage and failure of the mucosal barrier caused by acute or chronic alcohol consumption [59], or by a bout of gastroenteritis, would allow the immunogenic peptides resulting from the partial digestion of glutamines and gliadins to enter the lamina propria, where they could interact with immune cells, resulting in the production of AGA. Acute and chronic alcohol intake as well as gastroenteritis are not uncommon, and so this could explain both the high prevalence of AGA positivity in healthy subjects and the lack of clinical relevance of AGAs in both the healthy subjects and IBS patients.

Small-intestine endocrine cells in IBS and CD

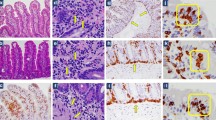

Abnormalities in the densities of the various types of endocrine cells in the small intestine have been reported in both IBS and CD (Table 2 and Figs. 1, 2 and 3) [60–78], and these abnormalities are considered to play an important role in the symptom development in both of these diseases [63, 79–81]. The pattern of changes in the densities of small-intestine endocrine cells in patients with CD is quite different from that in IBS and postinfectious IBS (PI-IBS).

Patients with both CD and IBS

It is not uncommon for patients with CD who consume a gluten-free diet (GFD) and suffer from IBS symptoms to present at the clinic. Reportedly 20–23.3 % of treated CD patients fulfill the symptom-based Rome criteria for IBS [82, 83]. A meta-analysis found that the pooled prevalence of IBS symptoms in patients with treated CD was 38 % [84]. Despite adhering to a GFD, patients with CD who exhibit IBS symptoms have a reduced quality of life as compared with those who do not [82, 83, 85]. It is possible that CD and IBS coexist in some patients [86]; however, it is more likely that the inflammation in CD does not subside completely in some patients after implementation of a GFD, and a low-grade inflammation [82] similar to that seen in PI-IBS may exist [36]. This assumption is supported by certain observations in other inflammatory bowel diseases such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, whereby 33–46 % of those with ulcerative colitis and 42–60 % of those with Crohn’s disease exhibit IBS symptoms during remission periods [87–91]. Fecal calprotectin is significantly elevated in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease patients with IBS in remission, compared to those without IBS-type symptoms, indicating the presence of occult inflammation [90].

IBS and NCGS

NCGS

NCGS receives widespread interest from the general public and mass media, and is often confused with the popular assumptions and speculations that the high carbohydrate content of wheat is responsible for negative health aspects such as obesity [92]. The situation is exacerbated by celebrities propagating these speculations as a means of losing weight. The concept of NCGS was first introduced in 1978 with a case report of a patient with abdominal pain and diarrhea who exhibited no abnormalities on small-intestine biopsy samples, whose symptoms improved when they changed to a GFD [93]. A study of eight adult females with abdominal pain, diarrhea, and small-intestine biopsy findings with no significant changes published in 1980 found that symptoms were relieved when the patients adhered to a GFD, and returned after a gluten challenge [94]. Similar results have been reported in patients with nonceliac IBS-like symptoms [95–97]. The withdrawal of wheat products was found to improve these symptoms in double-blind randomized, placebo-controlled studies involving patients with IBS-like symptoms [98, 99].

Whereas some studies involving experimental animals and humans have revealed that exposure to gluten induces intestinal low-grade inflammation, proliferation of peripheral blood monocytes, and enhancement of cytokine production [96, 100–102], others were unable to find any gluten-induced inflammation in NCGS [103]. Similar discrepancies have been reported regarding small-intestine permeability [96, 99, 104].

Is gluten responsible for NCGS?

As pointed out by Nijeboer et al. [105], in studies showing an effect on symptoms in NCGS patients, that effect was actually attributable to withdrawal of wheat rather than gluten [96, 98, 99]. A placebo-controlled, crossover study involving patients with IBS-like symptoms who were on a self-imposed GFD [106] found that the gastrointestinal symptoms consistently and significantly improved during a reduced intake of fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs), and these symptoms were not worsened by either a low- or high-dose challenge with gluten. Moreover, in a study involving adults who believed that they had NCGS, 24 % had uncontrolled symptoms despite consuming a GFD, 27 % did not strictly follow a GFD, and 65 % avoided other foods that contained high levels of FODMAPs as additional symptom triggers [107]. The findings of this study lend further support to the notion that the gluten in wheat is not the trigger of NCGS symptoms. However, in a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study on adults without CD or WA who believe that they suffer from NCGS showed that intake of small amounts of gluten increase the intestinal and extraintestinal symptoms significantly [108].

Together these results indicate that it is not clear that gluten is responsible for triggering NCGS symptoms; instead, it appears that it is the carbohydrate content (fructans and galactans) in the wheat that triggers these symptoms. Indigestible and poorly absorbed short-chain carbohydrates with chains containing up to ten sugars (which are collectively called FODMAPs) occur in a wide range of foods, including wheat, rye, vegetables, fruits, and legumes [109]. These carbohydrates exert osmotic effects in the large intestinal lumen, resulting in an increased water content. They are also fermented rapidly by intestinal bacteria, with consequent gas production [109–111]. Several studies, including some randomized, placebo-controlled studies, have shown that FODMAPS trigger gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS, and that a low-FODMAPs diet reduces symptom severity and improves the patient’s quality of life [112–119].

It is noteworthy that initiation of GFD without dietetic supervision or education can cause inadequacies of nutrient intake including fiber, thiamin, folate, vitamin A, magnesium, iron, and calcium [120]. Furthermore, it is difficult [121] and more expensive to follow a GFD.

Connection between IBS and NCGS

The definition of NCGS [28] coincides with that of IBS: they have the same gastrointestinal and extragastrointestinal symptoms. A point of difference may be that NCGS patients’ symptoms improve on withdrawal of gluten and return with gluten ingestion. However, it is not clear that gluten triggers the symptoms in NCGS patients; rather, there is compelling evidence that they are triggered by the fructan and galactan carbohydrate components, which are FODMAPs [106]. Furthermore, a considerable number of patients with NCGS experience no improvement of symptoms despite consuming a GFD, and a large number appear to avoid other food items that contain high levels of FODMAPs in addition to consuming a GFD [107]. It is possible that the frequency of IgG/IgA AGA is higher and the association with human leukocyte antigens (HLA) DQ2 and DQ8 is stronger in these patients [98]. As mentioned above, confirmation of AGA positivity is not a specific test, since a considerable number of healthy individuals are positive for this antibody and HLA DQ2 and DQ8 are common in healthy population.

The fructan contents in gluten-free bread (mostly made of rice/corn), bread made from white wheat flour, and bread made from spelt flour are 0.19 g/100 g, 0.68 g/100 g [6], and 0.14 g/100 g, respectively. In addition, spelt flour contains 16 % less protein (mostly gluten) compared to wheat [122]. Given the likelihood that it is the carbohydrate components of wheat that trigger symptoms in NCGS, spelt products would be a better alternative to wheat than a GFD, which is widely used by IBS patients [113, 114].

The following two statements from the research groups of Murray and Sanders should be emphasized in the ongoing debate regarding NCGS:

“Symptoms, symptom complexes, and symptom characteristics are rarely, if ever diagnostic” [100]

and

“We believe that further work is required in what we perceive as the research fertile crescent of gluten sensitivity! Only then can we better inform practicing clinicians on how to manage this group of patients” [86].

Conclusions

CD patients experience gastrointestinal symptoms similar to those seen in IBS patients, and are thus at risk of being misdiagnosed as having IBS. Therefore, CD should be excluded in IBS patients, regardless of the subtype. A considerable proportion (20–37 %) of CD patients suffer from IBS symptoms despite adherence to a GFD. It is likely that the inflammation caused by gluten intake does not completely subside in some CD patients, similar to what is seen in inflammatory bowel diseases, whereby a considerable number of patients exhibit IBS symptoms in the remission phase.

It is not clear that gluten triggers the symptoms in NCGS, but there is compelling evidence that carbohydrates (fructans and galactans) in the wheat does. Patients with NCGS exhibit the same gastrointestinal and extragastrointestinal symptoms as those with IBS. Withdrawal of wheat products reduces the symptom severity and improves the quality of life in both NCGS and IBS patients. Furthermore, there are no specific blood tests or radiological or endoscopic examinations that are diagnostic for either NCGS or IBS. It is likely that NCGS patients constitute a group of IBS patients who are self-diagnosed and have self-treated by adhering to a GFD.

References

Shewry PR. Wheat. J Exp Bot. 2009;60:1537–53.

Losowsky MS. A history of coeliac disease. Dig Dis. 2008;26:112–20.

Martin S. Against the grain: an overview of celiac disease. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20:243–50.

Aziz I, Sanders DS. Emerging concepts: from coeliac disease to non-coeliac gluten sensitivity. Proc Nutr Soc. 2012;71:576–80.

Shewry PR, Hawkesford MJ, Piironen V, Lampi AM, Gebruers K, Boros D, et al. Natural variation in grain composition of wheat and related cereals. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61:8295–303.

Biesiekierski JR, Rosella O, Rose R, Liels K, Barrett JS, Shepherd SJ, et al. Quantification of fructans, galacto-oligosacharides and other short-chain carbohydrates in processed grains and cereals. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24:154–76.

Tryfona T, Liang HC, Kotake T, Kaneko S, Marsh J, Ichinose H, et al. Carbohydrate structural analysis of wheat flour arabinogalactan protein. Carbohydr Res. 2010;345:2648–56.

Shewry PR, Halford NG. Cereal seed storage proteins: structures, properties and role in grain utilization. J Exp Bot. 2002;53:947–58.

Shewry PR, Miles MJ, Tatham AS. The prolamin storage proteins of wheat and related cereals. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1994;61:37–59.

Shewry PR, Halford NG, Belton PS, Tatham AS. The structure and properties of gluten: an elastic protein from wheat grain. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2002;357:133–42.

Piston F, Gil-Humanes J, Barro F. Integration of promoters, inverted repeat sequences and proteomic data into a model for high silencing efficiency of coeliac disease related gliadins in bread wheat. BMC Plant Biol. 2013;13:136.

Boettcher E, Crowe SE. Dietary proteins and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:728–36.

Sapone A, Bai JC, Ciacci C, Dolinsek J, Green PH, Hadjivassiliou M, et al. Spectrum of gluten-related disorders: consensus on new nomenclature and classification. BMC Med. 2012;10:13.

Sanders DS, Patel D, Stephenson TJ, Ward AM, McCloskey EV, Hadjivassiliou M, et al. A primary care cross-sectional study of undiagnosed adult coeliac disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:407–13.

Catassi C, Kryszak D, Bhatti B, Sturgeon C, Helzlsouer K, Clipp SL, et al. Natural history of celiac disease autoimmunity in a USA cohort followed since 1974. Ann Med. 2010;42:530–8.

Lohi S, Mustalahti K, Kaukinen K, Laurila K, Collin P, Rissanen H, et al. Increasing prevalence of coeliac disease over time. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1217–25.

Ludvigsson JF, Rubio-Tapia A, van Dyke CT, Melton 3rd LJ, Zinsmeister AR, Lahr BD, et al. Increasing incidence of celiac disease in a North American population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:818–24.

Rubio-Tapia A, Kyle RA, Kaplan EL, Johnson DR, Page W, Erdtmann F, et al. Increased prevalence and mortality in undiagnosed celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:88–93.

Rubio-Tapia A, Ludvigsson JF, Brantner TL, Murray JA, Everhart JE. The prevalence of celiac disease in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1538–44. quiz 1537, 1545.

Catassi C, Fabiani E, Ratsch IM, Coppa GV, Giorgi PL, Pierdomenico R, et al. The coeliac iceberg in Italy. A multicentre antigliadin antibodies screening for coeliac disease in school-age subjects. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1996;412:29–35.

Dube C, Rostom A, Sy R, Cranney A, Saloojee N, Garritty C, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease in average-risk and at-risk Western European populations: a systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:S57–67.

Not T, Horvath K, Hill ID, Partanen J, Hammed A, Magazzu G, et al. Celiac disease risk in the USA: high prevalence of antiendomysium antibodies in healthy blood donors. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:494–8.

Fasano A, Berti I, Gerarduzzi T, Not T, Colletti RB, Drago S, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in at-risk and not-at-risk groups in the United States: a large multicenter study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:286–92.

Zuidmeer L, Goldhahn K, Rona RJ, Gislason D, Madsen C, Summers C, et al. The prevalence of plant food allergies: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1210–8. e1214.

Mansueto P, Seidita A, D'Alcamo A, Carroccio A. Non-celiac gluten sensitivity: literature review. J Am Coll Nutr. 2014;33:39–54.

Di Sabatino A, Corazza GR. Coeliac disease. Lancet. 2009;373:1480–93.

Tatham AS, Shewry PR. Allergens to wheat and related cereals. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:1712–26.

Catassi C, Bai JC, Bonaz B, Bouma G, Calabro A, Carroccio A, et al. Non-Celiac Gluten sensitivity: the new frontier of gluten related disorders. Nutrients. 2013;5:3839–53.

Lundin KE. Non-celiac gluten sensitivity - why worry? BMC Med. 2014;12:86.

Zipser RD, Patel S, Yahya KZ, Baisch DW, Monarch E. Presentations of adult celiac disease in a nationwide patient support group. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:761–4.

Lo W, Sano K, Lebwohl B, Diamond B, Green PH. Changing presentation of adult celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:395–8.

Green PHR, Stavropoulos SN, Panagi SG, Goldstein SL, McMahon DJ, Absan H, et al. Characteristics of adult celiac disease in the USA: results of a national survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:126–31.

Bottaro G, Cataldo F, Rotolo N, Spina M, Corazza GR. The clinical pattern of subclinical/silent celiac disease: an analysis on 1026 consecutive cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:691–6.

Makharia GK, Baba CS, Khadgawat R, Lal S, Tevatia MS, Madan K, et al. Celiac disease: variations of presentations in adults. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2007;26:162–6.

Sharma M, Singh P, Agnihotri A, Das P, Mishra A, Verma AK, et al. Celiac disease: a disease with varied manifestations in adults and adolescents. J Dig Dis. 2013;14:518–25.

El-Salhy M. Irritable bowel syndrome: diagnosis and pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5151–63.

Reilly NR, Fasano A, Green PH. Presentation of celiac disease. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2012;22:613–21.

Heizer WD, Southern S, McGovern S. The role of diet in symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in adults: a narrative review. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1204–14.

van der Wouden EJ, Nelis GF, Vecht J. Screening for coeliac disease in patients fulfilling the Rome II criteria for irritable bowel syndrome in a secondary care hospital in The Netherlands: a prospective observational study. Gut. 2007;56:444–5.

Locke 3rd GR, Murray JA, Zinsmeister AR, Melton 3rd LJ, Talley NJ. Celiac disease serology in irritable bowel syndrome and dyspepsia: a population-based case–control study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:476–82.

Hin H, Bird G, Fisher P, Mahy N, Jewell D. Coeliac disease in primary care: case finding study. BMJ. 1999;318:164–7.

Shahbazkhani B, Forootan M, Merat S, Akbari MR, Nasserimoghadam S, Vahedi H, et al. Coeliac disease presenting with symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:231–5.

Catassi C, Kryszak D, Louis-Jacques O, Duerksen DR, Hill I, Crowe SE, et al. Detection of Celiac disease in primary care: a multicenter case-finding study in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1454–60.

Sanders DS, Carter MJ, Hurlstone DP, Pearce A, Ward AM, McAlindon ME, et al. Association of adult coeliac disease with irritable bowel syndrome: a case–control study in patients fulfilling ROME II criteria referred to secondary care. Lancet. 2001;358:1504–8.

Korkut E, Bektas M, Oztas E, Kurt M, Cetinkaya H, Ozden A. The prevalence of celiac disease in patients fulfilling Rome III criteria for irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Intern Med. 2010;21:389–92.

El-Salhy M, Lomholt-Beck B, Gundersen D. The prevalence of celiac disease in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Report. 2011;4:403–5.

Aziz I, Sanders DS. The irritable bowel syndrome-celiac disease connection. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2012;22:623–37.

Cash BD, Rubenstein JH, Young PE, Gentry A, Nojkov B, Lee D, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease among patients with nonconstipated irritable bowel syndrome is similar to controls. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1187–93.

Spiller R, Aziz Q, Creed F, Emmanuel A, Houghton L, Hungin P, et al. Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical management. Gut. 2007;56:1770–98.

Schyum AC, Rumessen JJ. Serological testing for celiac disease in adults. United European Gastroenterol J. 2013;1:319–25.

Sanders DS, Hurlstone DP, Stokes RO, Rashid F, Milford-Ward A, Hadjivassiliou M, et al. Changing face of adult coeliac disease: experience of a single university hospital in South Yorkshire. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78:31–3.

Cranney A, Zarkadas M, Graham ID, Butzner JD, Rashid M, Warren R, et al. The Canadian Celiac Health Survey. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1087–95.

Barratt SM, Leeds JS, Robinson K, Lobo AJ, McAlindon ME, Sanders DS. Prodromal irritable bowel syndrome may be responsible for delays in diagnosis in patients presenting with unrecognized Crohn's disease and celiac disease, but not ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:3270–5.

Elloumi H, El Assoued Y, Ghedira I, Ben Abdelaziz A, Yacoobi MT, Ajmi S. [Immunological profile of coeliac disease in a subgroup of patients with symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome]. Tunis Med. 2008;86:802–5.

Volta U, De Giorgio R. New understanding of gluten sensitivity. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9:295–9.

Volta U, Tovoli F, Cicola R, Parisi C, Fabbri A, Piscaglia M, et al. Serological tests in gluten sensitivity (nonceliac gluten intolerance). J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:680–5.

Ruuskanen A, Kaukinen K, Collin P, Huhtala H, Valve R, Maki M, et al. Positive serum antigliadin antibodies without celiac disease in the elderly population: does it matter? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1197–202.

Hadjivassiliou M, Gibson A, Davies-Jones GA, Lobo AJ, Stephenson TJ, Milford-Ward A. Does cryptic gluten sensitivity play a part in neurological illness? Lancet. 1996;347:369–71.

Rajendram R, Preedy VR. Effect of alcohol consumption on the gut. Dig Dis. 2005;23:214–21.

Dizdar V, Spiller R, Singh G, Hanevik K, Gilja OH, El-Salhy M, et al. Relative importance of abnormalities of CCK and 5-HT (serotonin) in Giardia-induced post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:883–91.

El-Salhy M, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. Is irritable bowel syndrome a stem cell disorder? World J Gastroenterol. 2014. In press.

El-Salhy M, Vaali K, Dizdar V, Hausken T. Abnormal small-intestinal endocrine cells in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3508–13.

El-Salhy M. The nature and implication of intestinal endocrine cell changes in coeliac disease. Histol Histopathol. 1998;13:1069–75.

Challacombe DN, Dawkins PD, Baker P. Increased tissue concentrations of 5-hydroxytryptamine in the duodenal mucosa of patients with coeliac disease. Gut. 1977;18:882–6.

Challacombe DN, Robertson K. Enterochromaffin cells in the duodenal mucosa of children with coeliac disease. Gut. 1977;18:373–6.

Wheeler EE, Challacombe DN. Quantification of enterochromaffin cells with serotonin immunoreactivity in the duodenal mucosa in coeliac disease. Arch Dis Child. 1984;59:523–7.

Polak JM, Pearse AG, Van Noorden S, Bloom SR, Rossiter MA. Secretin cells in coeliac disease. Gut. 1973;14:870–4.

Pietroletti R, Bishop AE, Carlei F, Bonamico M, Lloyd RV, Wilson BS, et al. Gut endocrine cell population in coeliac disease estimated by immunocytochemistry using a monoclonal antibody to chromogranin. Gut. 1986;27:838–43.

Sjolund K, Alumets J, Berg NO, Hakanson R, Sundler F. Enteropathy of coeliac disease in adults: increased number of enterochromaffin cells the duodenal mucosa. Gut. 1982;23:42–8.

Sjolund K, Alumets J, Berg NO, Hakanson R, Sundler F. Duodenal endocrine cells in adult coeliac disease. Gut. 1979;20:547–52.

Sjolund K, Hakanson R, Lundqvist G, Sundler F. Duodenal somatostatin in coeliac disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1982;17:969–76.

Jones JG, Elmes ME. The measurement of mucosal non-myelinated nerve fibre area and endocrine cell area in coeliac disease using morphometric analysis. Diagn Histopathol. 1982;5:183–8.

Besterman HS, Bloom SR, Sarson DL, Blackburn AM, Johnston DI, Patel HR, et al. Gut-hormone profile in coeliac disease. Lancet. 1978;1:785–8.

Enerback L, Hallert C, Norrby K. Raised 5-hydroxytryptamine concentrations in enterochromaffin cells in adult coeliac disease. J Clin Pathol. 1983;36:499–503.

Johnston CF, Bell PM, Collins BJ, Shaw C, Love AH, Buchanan KD. Reassessment of enteric endocrine cell hyperplasia in celiac disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 1988;35:285–8.

Buchan AM, Grant S, Brown JC, Freeman HJ. A quantitative study of enteric endocrine cells in celiac sprue. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1984;3:665–71.

Moyana TN, Shukoor S. Gastrointestinal endocrine cell hyperplasia in celiac disease: a selective proliferative process of serotonergic cells. Mod Pathol. 1991;4:419–23.

Di Sabatino A, Giuffrida P, Vanoli A, Luinetti O, Manca R, Biancheri P, et al. Increase in neuroendocrine cells in the duodenal mucosa of patients with refractory celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:258–69.

El-Salhy M, Gundersen D, Gilja OH, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. Is irritable bowel syndrome an organic disorder? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:384–400.

Camilleri M. Physiological underpinnings of irritable bowel syndrome: neurohormonal mechanisms. J Physiol. 2014;592:2967–80.

El-Salhy M, Seim I, Chopin L, Gundersen D, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. Irritable bowel syndrome: the role of gut neuroendocrine peptides. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2012;4:2783–800.

O'Leary C, Wieneke P, Buckley S, O'Regan P, Cronin CC, Quigley EM, et al. Celiac disease and irritable bowel-type symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1463–7.

Hauser W, Musial F, Caspary WF, Stein J, Stallmach A. Predictors of irritable bowel-type symptoms and healthcare-seeking behavior among adults with celiac disease. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:370–6.

Sainsbury A, Sanders DS, Ford AC. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome-type symptoms in patients with celiac disease: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:359–65. e351.

Barratt SM, Leeds JS, Robinson K, Shah PJ, Lobo AJ, McAlindon ME, et al. Reflux and irritable bowel syndrome are negative predictors of quality of life in coeliac disease and inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:159–65.

Ball AJ, Hadjivassiliou M, Sanders DS. Is gluten sensitivity a "No Man's Land" or a "Fertile Crescent" for research? Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:222–3. author reply 223–224.

Isgar B, Harman M, Kaye MD, Whorwell PJ. Symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in ulcerative colitis in remission. Gut. 1983;24:190–2.

Ansari R, Attari F, Razjouyan H, Etemadi A, Amjadi H, Merat S, et al. Ulcerative colitis and irritable bowel syndrome: relationships with quality of life. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:46–50.

Simren M, Axelsson J, Gillberg R, Abrahamsson H, Svedlund J, Bjornsson ES. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease in remission: the impact of IBS-like symptoms and associated psychological factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:389–96.

Keohane J, O'Mahony C, O'Mahony L, O'Mahony S, Quigley EM, Shanahan F. Irritable bowel syndrome-type symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a real association or reflection of occult inflammation? Am J Gastroenterol. 1788;2010(105):1789–94. quiz 1795.

Minderhoud IM, Oldenburg B, Wismeijer JA, van Berge Henegouwen GP, Smout AJ. IBS-like symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in remission; relationships with quality of life and coping behavior. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:469–74.

Davis W. Wheat belly: lose the wheat, loss the weight and find your path back to health. New York: Rodale; 2011.

Ellis A, Linaker BD. Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity? Lancet. 1978;1:1358–9.

Cooper BT, Holmes GK, Ferguson R, Thompson RA, Allan RN, Cooke WT. Gluten-sensitive diarrhea without evidence of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:801–6.

Campanella J, Biagi F, Bianchi PI, Zanellati G, Marchese A, Corazza GR. Clinical response to gluten withdrawal is not an indicator of coeliac disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:1311–4.

Vazquez-Roque MI, Camilleri M, Smyrk T, Murray JA, Marietta E, O'Neill J, et al. A controlled trial of gluten-free diet in patients with irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea: effects on bowel frequency and intestinal function. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:903–11. e903.

Kaukinen K, Turjanmaa K, Maki M, Partanen J, Venalainen R, Reunala T, et al. Intolerance to cereals is not specific for coeliac disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:942–6.

Carroccio A, Mansueto P, Iacono G, Soresi M, D'Alcamo A, Cavataio F, et al. Non-celiac wheat sensitivity diagnosed by double-blind placebo-controlled challenge: exploring a new clinical entity. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1898–906. quiz 1907.

Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Irving PM, Barrett JS, Haines M, Doecke JD, et al. Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without celiac disease: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:508–14. quiz 515.

Verdu EF, Armstrong D, Murray JA. Between celiac disease and irritable bowel syndrome: the "no man's land" of gluten sensitivity. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1587–94.

Carroccio A, Brusca I, Mansueto P, Pirrone G, Barrale M, Di Prima L, et al. A cytologic assay for diagnosis of food hypersensitivity in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:254–60.

Carroccio A, Brusca I, Mansueto P, D'Alcamo A, Barrale M, Soresi M, et al. A comparison between two different in vitro basophil activation tests for gluten- and cow's milk protein sensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)-like patients. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2013;51:1257–63.

Bucci C, Zingone F, Russo I, Morra I, Tortora R, Pogna N, et al. Gliadin does not induce mucosal inflammation or basophil activation in patients with nonceliac gluten sensitivity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1294–9. e1291.

Sapone A, Lammers KM, Casolaro V, Cammarota M, Giuliano MT, De Rosa M, et al. Divergence of gut permeability and mucosal immune gene expression in two gluten-associated conditions: celiac disease and gluten sensitivity. BMC Med. 2011;9:23.

Nijeboer P, Bontkes HJ, Mulder CJ, Bouma G. Non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Is it in the gluten or the grain? J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2013;22:435–40.

Biesiekierski JR, Peters SL, Newnham ED, Rosella O, Muir JG, Gibson PR. No effects of gluten in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity after dietary reduction of fermentable, poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:320–8. e323.

Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Shepherd SJ, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Characterization of Adults With a Self-Diagnosis of Nonceliac Gluten Sensitivity. Nutr Clin Pract. 2014;29:504–9.

Di Sabatino A, Volta U, Salvatore C, Biancheri P, Caio G, De Giorgio R, Di Stefano M, Corazza GR. Small Amounts of Gluten in Subjects With Suspected Nonceliac Gluten Sensitivity: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Cross-Over Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2015.01.029

Shepherd SJ, Lomer MC, Gibson PR. Short-chain carbohydrates and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:707–17.

Marcason W. What is the FODMAP diet? J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:1696.

Barrett JS, Gearry RB, Muir JG, Irving PM, Rose R, Rosella O, et al. Dietary poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates increase delivery of water and fermentable substrates to the proximal colon. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:874–82.

El-Salhy M, Ostgaard H, Gundersen D, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. The role of diet in the pathogenesis and management of irritable bowel syndrome (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2012;29:723–31.

Mazzawi T, Hausken T, Gundersen D, El-Salhy M. Effects of dietary guidance on the symptoms, quality of life and habitual dietary intake of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Rep. 2013;8:845–52.

Ostgaard H, Hausken T, Gundersen D, El-Salhy M. Diet and effects of diet management on quality of life and symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Report. 2012;5:1382–90.

Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:67–75. e65.

Barrett JS, Gibson PR. Fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAPs) and nonallergic food intolerance: FODMAPs or food chemicals? Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2012;5:261–8.

Ong DK, Mitchell SB, Barrett JS, Shepherd SJ, Irving PM, Biesiekierski JR, et al. Manipulation of dietary short chain carbohydrates alters the pattern of gas production and genesis of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1366–73.

Gibson PR, Shepherd SJ. Evidence-based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: The FODMAP approach. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:252–8.

Gibson PR, Shepherd SJ. Personal view: food for thought--western lifestyle and susceptibility to Crohn's disease. The FODMAP hypothesis Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1399–409.

Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR. Nutritional inadequacies of the gluten-free diet in both recently-diagnosed and long-term patients with coeliac disease. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2013;26:349–58.

Verrill L, Zhang Y, Kane R. Food label usage and reported difficulty with following a gluten-free diet among individuals in the USA with coeliac disease and those with noncoeliac gluten sensitivity. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2013;26:479–87.

Pattison AL, Appelbee M, Trethowan RM. Characteristics of modern triticale quality: glutenin and secalin subunit composition and mixograph properties. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62:4924–31.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from Helse-Vest and Helse-Fonna.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

E-SM delimited the topics, performed the bibliographic search, and drafted the manuscript; HJG, GOH, and HT contributed equally to the planning of the review, and made comments that improved the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

El-Salhy, M., Hatlebakk, J.G., Gilja, O.H. et al. The relation between celiac disease, nonceliac gluten sensitivity and irritable bowel syndrome. Nutr J 14, 92 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-015-0080-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-015-0080-6