Abstract

Purpose

Hypotension after induction of general anesthesia (GAIH) is common and is associated with postoperative complications including increased mortality. Collapsibility of the inferior vena cava (IVC) has good performance in predicting GAIH; however, there is limited evidence whether a preoperative fluid bolus in patients with a collapsible IVC can prevent this drop in blood pressure.

Methods

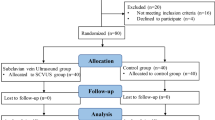

We conducted a single-centre randomized controlled trial with adult patients scheduled to undergo elective noncardiac surgery under general anesthesia (GA). Patients underwent a preoperative point-of-care ultrasound scan (POCUS) to identify those with a collapsible IVC (IVC collapsibility index ≥ 43%). Individuals with a collapsible IVC were randomized to receive a preoperative 500 mL fluid bolus or routine care (control group). Surgical and anesthesia teams were blinded to the results of the scan and group allocation. Hypotension after induction of GA was defined as the use of vasopressors/inotropes or a decrease in mean arterial pressure < 65 mm Hg or > 25% from baseline within 20 min of induction of GA.

Results

Forty patients (20 in each group) were included. The rate of hypotension after induction of GA was significantly reduced in those receiving preoperative fluids (9/20, 45% vs 17/20, 85%; relative risk, 0.53; 95% confidence interval, 0.32 to 0.89; P = 0.02). The mean (standard deviation) time to complete POCUS was 4 (2) min, and the duration of fluid bolus administration was 14 (5) min. Neither surgical delays nor adverse events occurred as a result of the study intervention.

Conclusion

A preoperative fluid bolus in patients with a collapsible IVC reduced the incidence of GAIH without associated adverse effects.

Study registration

ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05424510); first submitted 15 June 2022.

Résumé

Objectif

L’hypotension après induction de l’anesthésie générale (AG) est fréquente et est associée à des complications postopératoires, notamment à une augmentation de la mortalité. La collapsibilité de la veine cave inférieure (VCI) a été utilisée avec succès pour prédire la l’hypotension post-induction de l’AG; cependant, il existe peu de données probantes qu’un bolus liquidien préopératoire chez les patient·es présentant une collapsibilité de la VCI puisse prévenir cette baisse de la tension artérielle.

Méthode

Nous avons réalisé une étude randomisée contrôlée monocentrique auprès de patient·es adultes devant bénéficier d’une chirurgie non cardiaque non urgente sous anesthésie générale. Les patient·es ont passé une échographie préopératoire ciblée (POCUS) pour identifier les personnes présentant une collapsibilité de la VCI (indice de collapsibilité de la VCI ≥ 43 %). Les personnes présentant une collapsibilité de la VCI ont été randomisées à recevoir un bolus de liquide préopératoire de 500 mL ou des soins de routine (groupe témoin). Les équipes chirurgicales et d’anesthésie ne connaissaient pas les résultats de l’examen ni l’attribution des groupes. L’hypotension après induction de l’AG a été définie comme l’utilisation de vasopresseurs/inotropes ou une diminution de la tension artérielle moyenne < 65 mm Hg ou > 25 % par rapport aux valeurs de base dans les 20 minutes suivant l’induction de l’AG.

Résultats

Quarante patient·es (20 dans chaque groupe) ont été inclus·es. Le taux d’hypotension après induction de l’AG était significativement réduit chez les personnes recevant des liquides préopératoires (9/20, 45 % vs 17/20, 85 %; risque relatif, 0,53; intervalle de confiance à 95 %, 0,32 à 0,89; P = 0,02). Le temps moyen (écart type) pour compléter l’échographie ciblée était de 4 (2) min, et la durée de l’administration du bolus liquidien était de 14 (5) min. Ni retards chirurgicaux ni effets indésirables ne sont survenus à la suite de l’intervention à l’étude.

Conclusion

Un bolus liquidien préopératoire chez les patient·es présentant une collapsibilité de la VCI a réduit l’incidence d’hypotension après l’induction de l’anesthésie générale sans effets indésirables associés.

Enregistrement de l’étude

ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05424510); première soumission le 15 juin 2022.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bijker JB, van Klei WA, Kappen TH, van Wolfswinkel L, Moons KG, Kalkman CJ. Incidence of intraoperative hypotension as a function of the chosen definition: literature definitions applied to a retrospective cohort using automated data collection. Anesthesiology 2007; 107: 213–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.anes.0000270724.40897.8e

Sessler DI, Meyhoff CS, Zimmerman NM, et al. Period-dependent associations between hypotension during and for four days after noncardiac surgery and a composite of myocardial infarction and death: a substudy of the POISE-2 trial. Anesthesiology 2018; 128: 317–27. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0000000000001985

Monk TG, Saini V, Weldon BC, Sigl JC. Anesthetic management and one-year mortality after noncardiac surgery. Anesth Analg 2005; 100: 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ane.0000147519.82841.5e

Walsh M, Devereaux PJ, Garg AX, et al. Relationship between intraoperative mean arterial pressure and clinical outcomes after noncardiac surgery: toward an empirical definition of hypotension. Anesthesiology 2013; 119: 507–15. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0b013e3182a10e26

Salmasi V, Maheshwari K, Yang D, et al. Relationship between intraoperative hypotension, defined by either reduction from baseline or absolute thresholds, and acute kidney and myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort analysis. Anesthesiology 2017; 126: 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0000000000001432

Chen B, Pang QY, An R, Liu HL. A systematic review of risk factors for postinduction hypotension in surgical patients undergoing general anesthesia. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2021; 25: 7044–50. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_202111_27255

Gelman S. Venous function and central venous pressure: a physiologic story. Anesthesiology 2008; 108: 735–48. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0b013e3181672607

Wolff CB, Green DW. Clarification of the circulatory patho-physiology of anaesthesia—implications for high-risk surgical patients. Int J Surg 2014; 12: 1348–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.10.034

Seif D, Perera P, Mandavia D. Caval sonography in shock: a noninvasive method for evaluating intravascular volume in critically ill patients. J Ultrasound Med 2012; 31: 1885–90. https://doi.org/10.7863/jum.2012.31.12.1885

Nakamura K, Tomida M, Ando T, et al. Cardiac variation of inferior vena cava: new concept in the evaluation of intravascular blood volume. J Med Ultrason 2013; 40: 205–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10396-013-0435-6

Brennan JM, Ronan A, Goonewardena S, et al. Handcarried ultrasound measurement of the inferior vena cava for assessment of intravascular volume status in the outpatient hemodialysis clinic. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 1: 749–53. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.00310106

Zhang J, Critchley LA. Inferior vena cava ultrasonography before general anesthesia can predict hypotension after induction. Anesthesiology 2016; 124: 580–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0000000000001002

Purushothaman SS, Alex A, Kesavan R, Balakrishnan S, Rajan S, Kumar L. Ultrasound measurement of inferior vena cava collapsibility as a tool to predict propofol-induced hypotension. Anesth Essays Res 2020; 14: 199–202. https://doi.org/10.4103/aer.aer_75_20

Feissel M, Michard F, Faller JP, Teboul JL. The respiratory variation in inferior vena cava diameter as a guide to fluid therapy. Intensive Care Med 2004; 30: 1834–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-004-2233-5

Caplan M, Durand A, Bortolotti P, et al. Measurement site of inferior vena cava diameter affects the accuracy with which fluid responsiveness can be predicted in spontaneously breathing patients: a post hoc analysis of two prospective cohorts. Ann Intensive Care 2020; 10: 168. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-020-00786-1

Kent A, Bahner DP, Boulger CT, et al. Sonographic evaluation of intravascular volume status in the surgical intensive care unit: a prospective comparison of subclavian vein and inferior vena cava collapsibility index. J Surg Res 2013; 184: 561–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2013.05.040

Au AK, Steinberg D, Thom C, et al. Ultrasound measurement of inferior vena cava collapse predicts propofol-induced hypotension. Am J Emerg Med 2016; 34: 1125–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2016.03.058

Haldane JB. The mean and variance of χ2 when used as a test of homogeneity, when expectations are small. Biometrika 1940; 31: 346–55. https://doi.org/10.2307/2332614

Monk TG, Bronsert MR, Henderson WG, et al. Association between intraoperative hypotension and hypertension and 30-day postoperative mortality in noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 2015; 123: 307–19. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0000000000000756

Saugel B, Bebert EJ, Briesenick L, et al. Mechanisms contributing to hypotension after anesthetic induction with sufentanil, propofol, and rocuronium: a prospective observational study. J Clin Monit Comput 2022; 36: 341–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-021-00653-9

Bhimsaria SK, Bidkar PU, Dey A, et al. Clinical utility of ultrasonography, pulse oximetry and arterial line derived hemodynamic parameters for predicting post-induction hypotension in patients undergoing elective craniotomy for excision of brain tumors—a prospective observational study. Heliyon 2022; 8: e11208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11208

Ackland GL, Singh-Ranger D, Fox S, et al. Assessment of preoperative fluid depletion using bioimpedance analysis. Br J Anaesth 2004; 92: 134–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aeh015

Bundgaard-Nielsen M, Jørgensen CC, Secher NH, Kehlet H. Functional intravascular volume deficit in patients before surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2010; 54: 464–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02175.x

American Society of Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for preoperative fasting and the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration: application to healthy patients undergoing elective procedures: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on preoperative fasting and the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration. Anesthesiology 2017; 126: 376–93. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0000000000001452

Simpao AF, Wu L, Nelson O, et al. Preoperative fluid fasting times and postinduction low blood pressure in children. Anesthesiology 2020; 133: 523–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0000000000003343

Frykholm P, Disma N, Andersson H, et al. Pre-operative fasting in children: a guideline from the European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2022; 39: 4–25. https://doi.org/10.1097/eja.0000000000001599

Myrberg T, Lindelöf L, Hultin M. Effect of preoperative fluid therapy on hemodynamic stability during anesthesia induction, a randomized study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2019; 63: 1129–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/aas.13419

Paul A, Sriganesh K, Chakrabarti D, Reddy KR. Effect of preanesthetic fluid loading on postinduction hypotension and advanced cardiac parameters in patients with chronic compressive cervical myelopathy: a randomized controlled trial. J Neurosci Rural Pract 2022; 13: 462–70. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-1749459

Holte K, Sharrock NE, Kehlet H. Pathophysiology and clinical implications of perioperative fluid excess. Br J Anaesth 2002; 89: 622–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aef220

Holte K, Kehlet H. Fluid therapy and surgical outcomes in elective surgery: a need for reassessment in fast-track surgery. J Am Coll Surg 2006; 202: 971–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.01.003

Marjanovic G, Villain C, Juettner E, et al. Impact of different crystalloid volume regimes on intestinal anastomotic stability. Ann Surg 2009; 249: 181–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0b013e31818b73dc

Kulemann B, Timme S, Seifert G, et al. Intraoperative crystalloid overload leads to substantial inflammatory infiltration of intestinal anastomoses—a histomorphological analysis. Surgery 2013; 154: 596–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2013.04.010

Pang Q, Liu H, Chen B, Jiang Y. Restrictive and liberal fluid administration in major abdominal surgery. Saudi Med J 2017; 38: 123–31. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2017.2.15077

Nisanevich V, Felsenstein I, Almogy G, Weissman C, Einav S, Matot I. Effect of intraoperative fluid management on outcome after intraabdominal surgery. Anesthesiology 2005; 103: 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-200507000-00008

Brandstrup B, Tønnesen H, Beier-Holgersen R, et al. Effects of intravenous fluid restriction on postoperative complications: comparison of two perioperative fluid regimens: a randomized assessor-blinded multicenter trial. Ann Surg 2003; 238: 641–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000094387.50865.23

Chappell D, Jacob M, Hofmann-Kiefer K, Conzen P, Rehm M. A rational approach to perioperative fluid management. Anesthesiology 2008; 109: 723–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0b013e3181863117

Ceruti S, Anselmi L, Minotti B, et al. Prevention of arterial hypotension after spinal anaesthesia using vena cava ultrasound to guide fluid management. Br J Anaesth 2018; 120: 101–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2017.08.001

Kimori K, Tamura Y. Feasibility of using a pocket-sized ultrasound device to measure the inferior vena cava diameter of patients with heart failure in the community setting: a pilot study. J Prim Care Community Health 2020; 11: https://doi.org/10.1177/2150132720931345

Beaubien-Souligny W, Rola P, Haycock K, et al. Quantifying systemic congestion with point-of-care ultrasound: development of the venous excess ultrasound grading system. Ultrasound J 2020; 12: 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13089-020-00163-w

Author contributions

Elad Dana contributed to the conceptualization and design of the manuscript, methodology, acquisition, data curation and interpretation, and drafting the article. Cristian Arzola helped with the study conception and design, validation, writing, reviewing, editing, and administration. James Khan contributed to the study conceptualization and design, methodology, writing, reviewing, and editing.

Disclosures

None.

Funding statement

None.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Philip M. Jones, Deputy Editor-in-Chief, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is accompanied by an Editorial. Please see Can J Anesth 2024; https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-024-02747-9.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Dana, E., Arzola, C. & Khan, J.S. Prevention of hypotension after induction of general anesthesia using point-of-care ultrasound to guide fluid management: a randomized controlled trial. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-024-02748-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-024-02748-8