Abstract

Purpose

Legitimate opioid prescriptions can increase the risk of misuse, addiction, and overdose of opioids in children and adolescents. This study aimed to describe the prescribing patterns of discharge opioid analgesics following inpatient visits and to determine patient and prescriber characteristics that are associated with prolonged opioid prescription.

Methods

In a historical cohort study, we identified patients discharged from hospital with an opioid analgesic prescription in a tertiary pediatric hospital from 1 January 2016 to 30 June 2017. The primary outcome was the duration of opioid prescription in number of days. We assessed the association between patient and prescriber characteristics and an opioid prescription duration > five days using a generalized estimating equation to account for clustering due to repeated admissions of the same patient.

Results

During the 18-month study period, 15.4% of all admitted patients (3,787/24,571) were given a total of 3,870 opioid prescriptions at discharge. The median [interquartile range] prescribed duration of outpatient opioid therapy was 3.75 [3.00–5.00] days. Seventy-seven percent of the opioid prescriptions were for five days or less. Generalized estimating equation analysis revealed that hospital stay > four days, oxycodone prescription, and prescription by clinical fellows and the orthopedics service were all independently associated with a discharge opioid prescription of > five days.

Conclusions

Most discharge opioids for children were prescribed for less than five days, consistent with current guidelines for adults. Nevertheless, the dosage and duration of opioids prescribed at discharge varied widely.

Résumé

Objectif

Les ordonnances légales d’opioïdes peuvent augmenter le risque d’abus, de dépendance et de surdose d’opioïdes chez les enfants et les adolescents. Cette étude avait pour objectif de décrire les schémas de prescription d’analgésiques opioïdes au congé des séjours hospitaliers et à déterminer les caractéristiques des patients et des prescripteurs qui sont associées à la prescription prolongée d’opioïdes.

Méthode

Dans une étude de cohorte historique, nous avons identifié les patients ayant reçu leur congé de l’hôpital avec une ordonnance d’analgésiques opioïdes dans un hôpital pédiatrique de soins tertiaires entre le 1er janvier 2016 et le 30 juin 2017. Le critère d’évaluation principal était la durée de la prescription d’opioïdes en nombre de jours. Nous avons évalué l’association entre les caractéristiques des patients et des prescripteurs et la durée d’une ordonnance d’opioïdes > cinq jours à l’aide d’une équation d’estimation généralisée pour tenir compte du regroupement dû aux admissions répétées d’un même patient.

Résultats

Au cours de la période d’étude de 18 mois, 15,4 % de tous les patients admis (3787/24 571) ont reçu un total de 3870 ordonnances d’opioïdes à leur congé. La durée de prescription médiane [écart interquartile] du traitement d’opioïdes hors hôpital était de 3,75 [3,00-5,00] jours. Soixante-dix-sept pour cent des ordonnances d’opioïdes étaient de cinq jours ou moins. L’analyse de l’équation d’estimation généralisée a révélé qu’un séjour à l’hôpital > quatre jours, une prescription d’oxycodone et la prescription par des fellows cliniques et le service d’orthopédie ont tous été indépendamment associés à une ordonnance d’opioïdes au congé > cinq jours.

Conclusion

La plupart des opioïdes prescrits au congé pour les enfants ont été prescrits pour moins de cinq jours, conformément aux lignes directrices actuelles pour les adultes. Néanmoins, la posologie et la durée des opioïdes prescrits au congé variaient considérablement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The prescription opioid epidemic is a major public health concern in North America. Although attention has focused mainly on adults, children and adolescents are also at risk of opioid misuse, overdose, and diversion. There has been a steady increase in the rate of hospital admissions and pediatric critical care unit hospitalizations between 2004 and 2015 because of pediatric opioid ingestions.1 The rate of death due to opioid overdose among children and adolescents has alarmingly increased more than three-fold between 1999 and 2016.2 In a recent USA survey, 3.8% of adolescents have engaged in opioid misuse or have an opioid use disorder.3 Through unused prescriptions, healthcare providers may inadvertently add to the supply of opioids within the community, which may contribute to the problem of opioid misuse and diversion through excess availability.

Opioid analgesics are widely used for treating moderate to severe pain in children. They are frequently started in children while in hospital and continued following hospital discharge. Nevertheless, healthcare providers often overprescribe opioids, leaving excess doses available and frequently unsecured in the home. Prior studies found that 58–75% of opioid doses dispensed to pediatric patients were not consumed, and 80% of families did not dispose of the leftover opioids.4,5,6 Unused opioids available in the home can lead to unintended consequences. Younger children are particularly susceptible to accidental overdose of unsecured prescription opioids in the home.7 Among high school seniors who reported non-medical use of prescription opioids, 80% accessed leftover medications from a legitimate prescription.8 Adolescents reported obtaining prescription opioids most frequently from friends or relatives.3 Furthermore, short-term use of opioids to treat pain has a risk of precipitating further misuse in some at-risk youth.9

Because of these concerning trends, there is an increasing emphasis on safer opioid prescribing practices by physicians. Several states in the USA and Canadian provinces have issued guidelines on the duration of opioid therapy for acute pain in adults.10,11 Although organizations such as the Society for Pediatric Anesthesia and the American Pediatric Surgical Association (APSA) have created expert consensus guidelines on the use of opioids for acute postsurgical pain, these do not provide specific recommendations on dosing or length of therapy for children.12,13 As such, pediatric physicians are left without clear guidance on how to safely and responsibly prescribe opioids to children. To develop such guidelines, a better understanding of the current opioid prescribing pattern in pediatric patient populations is required. Nevertheless, few research studies have specifically looked at the pediatric population.4,5,14 In this study, we aimed to 1) describe the opioid prescribing patterns of discharge opioid analgesics following inpatient visits and 2) determine the patient and prescriber characteristics that are associated with receiving an opioid prescription > five days. Our primary outcome was the duration of opioid prescription in number of days.

Methods

This manuscript has been prepared in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guideline.15 The study design was a historical cohort study, retrospectively analyzing data of all patients aged ≤ 18 yr discharged from an inpatient unit who received a discharge outpatient prescription for an opioid analgesic between 1 January 2016 and 30 June 2017 at a single tertiary pediatric teaching hospital (The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada). This project was approved by the institutional Research Ethics Board (The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada; REB# 1000058987) and consent was waived given the deidentified and retrospective nature of the data collected.

Patients were identified using a retrospective search of the hospital’s electronic medical record (EMR) system. The initial electronic search identified patients who were discharged with an opioid analgesic following an inpatient hospital admission. After the initial search, we excluded patients over the age of 18 yr and patients discharged to another hospital or chronic care facility, and prescriptions with missing data were removed from the final data analysis.

For each inpatient discharge, we collected information on the patient’s age, sex, weight, primary diagnosis, admitting specialty, and hospital length of stay. For each identified discharge prescription, we collected data on the type of opioid, dose prescribed, dosing frequency, number of doses prescribed, prescribing service, and prescriber type (staff physician, clinical fellow, resident, or nurse practitioner). All opioid dosing data were converted to oral morphine equivalents based on standard conversion ratios.16 The primary outcome of this study was the duration of opioid prescription in number of days. This was calculated as the number of days an opioid prescription would last if the patient took a prescribed dose at every possible time interval until completion. The prescription was excluded from final analysis if any of the variables needed to make this calculation were missing.

Data analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics for demographic and prescription data. Data are presented as median [interquartile range (IQR)]. We performed univariable statistical comparisons using the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test for continuous variables or Chi square test for categorical variables. To control for possible confounding among variables and to take into account patients with multiple episodes, we used a generalized estimating equation (GEE) accounting for clustering due to repeated admissions of the same patient to predict the incidence of prolonged prescriptions. The results are expressed as the regression coefficient and standard error, the 95% confidence interval (CI), and P values. We used backward selection to determine the independent predictors for prolonged prescriptions using a cut-off of P > 0.05 for removal. We used the overall area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve as a measure of discrimination between those with and without prolonged prescriptions. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant for all tests. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 14.2 for Mac OS (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Characteristics of opioid prescriptions

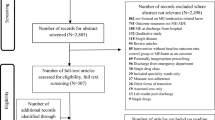

During the 18-month study period, a total of 24,571 patients were discharged following a hospital admission. The initial retrospective search of the EMR resulted in 4,239 discharge opioid analgesic prescriptions. After excluding duplicate records (n = 310) and patients discharged to another hospital or chronic care facility (n = 59), we identified 3,787 patients (15.4%) who received a total of 3,870 discharge opioid prescriptions. This includes 34 patients who had more than one admission during the study period and 51 patients who received more than one opioid prescription at discharge. After excluding prescriptions with missing amount or duration of doses prescribed (n = 594), a total of 3,276 opioid analgesic prescriptions were included in the analysis (Fig. 1). The median [IQR] age of our patient cohort was 8 [4–13] yr, and 55.4% of patients were male (Table 1).

Morphine was the most frequently prescribed opioid, accounting for 87.4% of the prescriptions, followed by hydromorphone (10.0%) and oxycodone (2.3%). Extended-release opioids were rarely prescribed, accounting for only 0.3% of prescriptions. Only two patients received a combination agent (oxycodone/acetaminophen). Of all prescriptions, 90.6% were written by surgical services. The most common prescribing services were orthopedics, accounting for 41.6% of the prescriptions, followed by otolaryngology (26.0%) and plastic surgery (13.7%). Residents (80.0%) and clinical fellows (18.9%) were responsible for writing the majority of prescriptions (Table 2). There were a total of 364 prescribers in our study who each issued between 1 and 103 prescriptions.

Of the 3,276 prescriptions, opioids were prescribed for a median [IQR] of 3.75 [3.00–5.00] days, with a range of 0.17–50.00 days. About 23% of prescriptions were prescribed for five days or more (Fig. 2). In the cohort of 759 prescriptions with > five day duration, 19 were prescribed by medical services; they comprised 9.2% of the total prescriptions and 2.5% of the prescriptions > five days. The median [IQR] number of doses of opioids prescribed was 20 [15–30]. The median [IQR] opioid dose was 0.18 [0.11–0.21] morphine milligram equivalents (MME)·kg−1, and the median [IQR] 24-hr dose was 0.96 [0.62–1.21] MME·kg−1·day−1.

The most common discharge diagnoses associated with opioid prescriptions were surgical procedures, including supracondylar fracture repair (n = 383; 9.9%), adenotonsillectomy (n = 299; 7.7%), femur fracture repair (n = 190; 4.4%), and posterior spinal fusion (n = 116; 3.0%). The median (range) number of days of opioid prescription were 5 (1–25) for supracondylar fracture, 3 (1–10) for adenotonsillectomy, 5 (1–14) for femur fracture, and 7 (1–33) for posterior spinal fusion (Fig. 3).

Factors associated with a longer prescription duration

Prescriptions with > five days duration were considered “prolonged” in our study. This cut-off was chosen because the likelihood of chronic opioid use increases sharply after the fifth day of opioid therapy for acute pain in adults.17 In the univariable analysis, prolonged prescriptions were significantly associated with older age of the patient, prescription by clinical fellows, prescription by the orthopedics service, certain types of opioids such as oxycodone and hydromorphone, and a longer hospital stay (Table 3). The results of the GEE are presented in Table 4, and suggest that hospital stay > four days, oxycodone prescription, and prescription by clinical fellows and the orthopedics service were all independently associated with prolonged prescriptions. The area under the ROC for our model was 0.719 (95% CI, 0.698 to 0.739).

Discussion

In this retrospective analysis of discharge opioid prescribing practice over an 18-month period in a tertiary pediatric hospital, most discharge opioid prescriptions were prescribed for less than five days, consistent with current guidelines for adults.11,18 Nevertheless, the dosage and duration of opioids prescribed at time of discharge varied widely.

We found that approximately 15% of pediatric patients discharged from the hospital after an inpatient stay were prescribed an opioid analgesic. This is consistent with data from the adult population, which showed that 15% of patients admitted to the hospital filled an opioid prescription within seven days of discharge.19 Seventy-seven percent of the opioid prescriptions in this study were prescribed for five days or less. Given that 58–75% of opioids prescribed are not consumed at home in pediatric patients, using five days as a threshold is a conservative estimate of the prevalence of prolonged prescriptions.4,5,6 Had we chosen a time frame of greater than three days for prolonged duration as suggested by some guidelines, 75% of the prescriptions in this study would have met this definition. We also observed that 13% of the prescriptions were prescribed for longer than seven days, and the longest was 50 days.

In our analysis, patients who received a prolonged opioid prescription tended to be hospitalized longer, received an oxycodone prescription, had the prescription written by a fellow physician, and were admitted to the orthopedics service. A longer hospital stay was associated with a longer duration of opioid prescription. An important factor that prolongs hospital stay following complex surgery is inadequate control of postoperative pain.20 Therefore, strategies such as enhanced recovery pathways that incorporate multimodal analgesia for complex surgeries that have been shown to improve pain control, reduce opioid consumption, and lower hospital length of stay should be considered to decrease the need for prolonged opioid use.21,22

Although oxycodone was associated with prolonged opioid prescription in the multivariate analysis, it was rarely prescribed in our study population. This finding differs from discharge opioid prescribing practices in USA hospitals, where oxycodone is commonly prescribed to children and adolescents.4 The use of oxycodone has been associated with a higher abuse potential compared with other opioids.23 In our assessment, its use should be minimized given that legitimate short-term opioid use during adolescence is associated with an increased risk of future misuse in some youth, including youth with a low predisposition to misuse.9

In our study, 97% of the discharge prescriptions were written by residents or clinical fellows. We observed large variability between individual providers in the percentage of longer prescriptions, ranging between 0 and 92% (Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM], eFig. 1). This variability may be explained by a lack of formal education on best practices in opioid prescribing for trainees at all levels. In a recent national survey of Canadian pediatric surgeons, 84% of responders declared that there was no formal training for residents/fellows in pain control and opioid prescribing at their institution.24 Research has also shown that surgical trainees who received formal education in postoperative pain control were significantly less likely to prescribe higher doses of opioids than trainees without formal education.25 Prescription provided by the orthopedics service was another predictor for longer prescriptions. In adults, major orthopedic surgery has been associated with higher postoperative pain intensities compared with other types of surgeries.26 This patient cohort provides a focus for improvement including providing multimodal analgesia, using regional analgesic techniques whenever possible, and providing provider and patient opioid safety education.

Although our prescribing practices mostly comply with current adult guidelines, when we examined opioid prescribing patterns for specific common diagnoses, we found significant variations in the duration of opioids prescribed and the 24-hr opioid dose following the same surgical indication (ESM, eFig. 2). Several recent studies have looked at opioid prescribing patterns following specific surgical procedures in children, and they similarly reported a wide variation in the number of days of opioid prescription for patients after surgeries such as pediatric appendectomy and umbilical hernia repair.27,28,29,30 Patients admitted with a diagnosis of supracondylar fracture in our study were discharged with opioid prescriptions with a median (range) of 20 (4–100) doses. Recent research from a single pediatric trauma centre on a cohort of 81 children undergoing closed reduction and percutaneous pinning of supracondylar humeral fracture showed they used an average of only 4.8 doses of opioid analgesics following discharge; 22% of patients required no opioid doses at all.31 In patients undergoing posterior spinal fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, Grant et al. reported that patients used a mean of 66% of the prescribed opioid analgesic doses.32 A survey conducted by the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America asked their members how long they expected to treat severe pain, most likely reflecting the amount of opioid medication prescribed. The responses varied considerably—usually less than a week, but for some practitioners up to four weeks or more for procedures such as knee arthroscopy, hip procedures, and spinal fusion.33 Some providers may overprescribe because they are uncertain about the duration of pain or because they cannot provide close follow-up. Development of pediatric procedure-specific opioid prescribing guidelines based on patient-reported data are urgently needed to reduce overprescribing.

Research in adults has shown that opioid prescription protocols along with preoperative counselling, multimodal analgesia, and considering inpatient analgesic requirements can significantly reduce dispensed opioids without increasing refill requests and pain scores.34 Without a pediatric guideline that provides specific recommendations on dosing or length of therapy for opioids, we suggest that the following steps be considered when prescribing opioids to children and adolescents at time of discharge to mitigate opioid-related risk:

-

1)

Formal opioid prescribing and pain management education should be incorporated into pediatric and surgical training programs.

-

2)

Prescribers need to better match the amount of opioid prescribed to a specific patient’s requirement. A simple method is to take into account the patient’s in-hospital usage within the 24 hr prior to discharge as a guide to determine the prescribing dose.35

-

3)

Nonopioid analgesics and targeted used of perioperative regional or neuraxial anesthesia techniques as part of an opioid-sparing regimen should be considered, as recommended by the recently published APSA expert consensus guideline for opioid prescribing in children and adolescents.13

-

4)

For patients in higher-risk groups, such as those requiring longer hospital stays and undergoing orthopedic surgeries associated with severe pain, close follow-up is needed and programs such as a Transitional Pain Service can be used to ensure close monitoring and appropriate weaning following discharge.36

Limitations

Limitations of this study include its retrospective design and data collection. We did not collect data on whether the prescription was filled, how much opioid was used, and how well pain was controlled at home. Nevertheless, recent investigations into pediatric home opioid consumption at surgical discharge from our institution showed that two thirds of opioids prescribed were unused.6 We also did not collect data on inpatient analgesic requirements, which determines postdischarge opioid requirements but not always the prescription given. Our study included patients with hematological/oncological conditions who are more likely to have severe and prolonged pain requiring longer treatment with opioid analgesics. Nevertheless, patients discharged from the hematology/oncology service comprised 1.7% of the total prescriptions and only 1.3% of prescriptions longer than five days. Another limitation is that we were unable to differentiate between patients on chronic opioids prior to admission and opioid naïve patients, which would account for large variations in opioid needs, although this is relatively uncommon in children.37 Such data were difficult to extract from the EMR system. We also excluded 15% of prescriptions because of missing data. Although we do not believe there are any systemic differences between prescriptions with and without missing data, the proportions of missing data are significant and may have affected our outcomes. Finally, this study was performed at a single academic tertiary children’s hospital and our results may not be widely generalizable to other centres.

Conclusions

Overall, most opioid prescribing practices for discharge analgesics in this single-centre academic pediatric hospital were broadly consistent with current adult guidelines. Nevertheless, we observed a wide variation in dosage and duration of opioids prescribed at discharge, even for the same discharge diagnoses. Factors associated with a longer opioid prescription included longer hospital stay, prescription for oxycodone, prescription provided by clinical fellows, and prescription by the orthopedics service. We identified subgroups of patients who had a higher probability of being prescribed opioids for longer and prescribers who were more likely to dispense longer prescriptions. Future studies should focus on actual postdischarge opioid use and develop targeted strategies to minimize opioid risk in these patient populations.

References

Kane JM, Colvin JD, Bartlett AH, Hall M. Opioid-related critical care resource use in US children's hospitals. Pediatrics 2018; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3335.

Gaither JR, Shabanova V, Leventhal JM. US national trends in pediatric deaths from prescription and illicit opioids, 1999-2016. JAMA Netw Open 2018; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6558.

Hudgins JD, Porter JJ, Monuteaux MC, Bourgeois FT. Prescription opioid use and misuse among adolescents and young adults in the United States: a national survey study. PLoS Med 2019; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002922.

Monitto CL, Hsu A, Gao S, et al. Opioid prescribing for the treatment of acute pain in children on hospital discharge. Anesth Analg 2017; 125: 2113-22.

Hunsberger JB, Hsu A, Yaster M, et al. Physicians prescribe more opioid than needed to treat pain in children after outpatient urological procedures: an observational cohort study. Anesth Analg 2019; 131: 866-75.

Caldeira-Kulbakas M, Stratton C, Roy R, Bordman W, Mc Donnell C. A prospective observational study of pediatric opioid prescribing at postoperative discharge: how much is actually used? Can J Anesth 2020; 67: 866-76.

Finkelstein Y, Macdonald EM, Gonzalez A, Sivilotti ML, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN. Overdose risk in young children of women prescribed opioids. Pediatrics 2017; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2887.

McCabe SE, West BT, Boyd CJ. Leftover prescription opioids and nonmedical use among high school seniors: a multi-cohort national study. J Adolescent Health 2013; 52: 480-5.

Miech R, Johnston L, O'Malley PM, Keyes KM, Heard K. Prescription opioids in adolescence and future opioid misuse. Pediatrics 2015; 136: e1169-77.

Agarwal S, Bryan JD, Hu HM, et al. Association of state opioid duration limits with postoperative opioid prescribing. JAMA Netw Open 2019; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.

Advisory Committee. Opioid Prescribing for Acute Pain - Care for People 15 Years of Age and Older. Toronto: Health Quality Ontario; 2018. Available from URL: https://www.hqontario.ca/portals/0/documents/evidence/quality-standards/qs-opioid-acute-pain-clinician-guide-en.pdf (accessed October 2021).

Cravero JP, Agarwal R, Berde C, et al. The Society for Pediatric Anesthesia recommendations for the use of opioids in children during the perioperative period. Paediatr Anaesth 2019; 29: 547-71.

Kelley-Quon LI, Kirkpatrick MG, Ricca RL, et al. Guidelines for opioid prescribing in children and adolescents after surgery: an expert panel opinion. JAMA Surg 2021; 156: 76-90.

Voepel-Lewis T, Wagner D, Tait AR. Leftover prescription opioids after minor procedures: an unwitting source for accidental overdose in children. JAMA Pediatr 2015; 169: 497-8.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007; 335: 806-8.

Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. CMAJ 2017; 189: E659-66.

Shah A, Hayes CJ, Martin BC. Characteristics of initial prescription episodes and likelihood of long-term opioid use - United States, 2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017; 66: 265-9.

Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain--United States, 2016. JAMA 2016; 315: 1624-45.

Jena AB, Goldman D, Karaca-Mandic P. Hospital prescribing of opioids to Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176: 990-7.

Sultan AA, Berger RJ, Cantrell WA, et al. Predictors of extended length of hospital stay in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients undergoing posterior segmental instrumented fusion: an analysis of 407 surgeries performed at a large academic center. Spine 2019; 44: 715-22.

Muhly WT, Sankar WN, Ryan K, et al. Rapid recovery pathway after spinal fusion for idiopathic scoliosis. Pediatrics 2016; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-1568.

Holmes DM, Polites SF, Roskos PL, Moir CR. Opioid use and length of stay following minimally invasive pectus excavatum repair in 436 patients - benefits of an enhanced recovery pathway. J Pediatr Surg 2019; 54: 1976-83.

Wightman R, Perrone J, Portelli I, Nelson L. Likeability and abuse liability of commonly prescribed opioids. J Med Toxicol 2012; 8: 335-40.

Zani-Ruttenstock E, Sozer A, O'Neill Trudeau M, Fecteau A. First national survey on opioids prescribing practices of Canadian pediatric surgeons. J Pediatr Surg 2020; 55: P954-8.

Prigoff JG, Titan AL, Fields AC, et al. The effect of surgical trainee education on opioid prescribing: an international evaluation. J Surg Educ 2020; 77: 1490-5.

Gerbershagen HJ, Aduckathil S, van Wijck AJ, Peelen LM, Kalkman CJ, Meissner W. Pain intensity on the first day after surgery: a prospective cohort study comparing 179 surgical procedures. Anesthesiology 2013; 118: 934-44.

Horton JD, Munawar S, Corrigan C, White D, Cina RA. Inconsistent and excessive opioid prescribing after common pediatric surgical operations. J Pediatr Surg 2019; 54: 1427-31.

Cartmill RS, Yang DY, Fernandes-Taylor S, Kohler JE. National variation in opioid prescribing after pediatric umbilical hernia repair. Surgery 2019; 165: 838-42.

Sonderman KA, Wolf LL, Madenci AL, et al. Opioid prescription patterns for children following laparoscopic appendectomy. Annals Surg 2020; 272: 1149-57.

Anderson KT, Bartz-Kurycki MA, Ferguson DM, et al. Too much of a bad thing: discharge opioid prescriptions in pediatric appendectomy patients. J Pediatr Surg 2018; 53: 2374-7.

Nelson SE, Adams AJ, Buczek MJ, Anthony CA, Shah AS. Postoperative pain and opioid use in children with supracondylar humeral fractures: balancing analgesia and opioid stewardship. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2019; 101: 119-26.

Grant DR, Schoenleber SJ, McCarthy AM, et al. Are we prescribing our patients too much pain medication? Best predictors of narcotic usage after spinal surgery for scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2016; 98: 1555-62.

Raney EM, van Bosse HJ, Shea KG, Abzug JM, Schwend RM. Current state of the opioid epidemic as it pertains to pediatric orthopaedics from the Advocacy Committee of the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America. J Pediatr Orthop 2018; 38: e238-44.

Mark J, Argentieri DM, Gutierrez CA, et al. Ultrarestrictive opioid prescription protocol for pain management after gynecologic and abdominal surgery. JAMA Netw Open 2018; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5452.

Clarke HA, Manoo V, Pearsall EA, et al. Consensus statement for the prescription of pain medication at discharge after elective adult surgery. Can J Pain 2020; 4: 67-85.

Vetter TR, Kain ZN. Role of the perioperative surgical home in optimizing the perioperative use of opioids. Anesth Analg 2017; 125: 1653-7.

Rosenbloom BN, Pagé MG, Isaac L, et al. Pediatric chronic postsurgical pain and functional disability: a prospective study of risk factors up to one year after major surgery. J Pain Res 2019; 12: 3079-98.

Author contributions

Naiyi Sun contributed to all aspects of this manuscript, including study conception and design; acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data; and drafting the article. Benjamin E. Steinberg contributed to acquisition of data and drafting of the article. David Faraoni contributed to analysis and interpretation of data and drafting of the article. Lisa Isaac contributed to study conception and design and drafting of the article

Disclosures

None.

Funding statement

None.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Stephan K.W. Schwarz, Editor-in-Chief, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, N., Steinberg, B.E., Faraoni, D. et al. Variability in discharge opioid prescribing practices for children: a historical cohort study. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 69, 1025–1032 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-021-02160-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-021-02160-6