Abstract

Purpose

While studies report on perceptions of family participation in delirium prevention, little is known about the use of family-administered delirium detection tools in the care of critically ill patients. This study sought the perspectives of patients, their family members, and healthcare providers on the use of family-administered delirium detection tools to detect delirium in critically ill patients and barriers and facilitators to using family-administered delirium detection tools in patient care.

Methods

In this qualitative study, critical care providers (five physicians, six registered nurses) and participants from the Family ICU Delirium Detection Study (seven past patients and family members) took part in four focus groups at one hospital in Calgary, Alberta.

Results

Key themes identified following thematic analysis from 18 participants included: 1) perceptions of acceptability of family-administered delirium detection (e.g., family feels valued, intensive care unit (ICU) care team may not use a family member’s results, intensification of work load), 2) considerations regarding feasibility (e.g., insufficient knowledge, healthcare team buy-in), and 3) overarching strategies to support implementation into routine patient care (e.g., value of family-administered delirium detection for patients and families is well understood in the clinical context, regular communication between the family and ICU providers, an electronic version of the tool).

Conclusions

Patients, family members and healthcare providers who participated in the focus groups perceived family participation in delirium detection and the use of family-administered delirium detection tools at the bedside as feasible and of value to patient care and family member coping.

Trial registration

www.ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03379129); registered 15 December 2017.

Résumé

Objectif

Bien que certaines études rapportent les perceptions concernant la participation de la famille à la prévention du delirium, on connaît peu l’utilisation d’outils de détection du delirium administrés par la famille dans les soins aux patients gravement malades. Cette étude a cherché à connaître les points de vue des patients, des membres de leur famille et des fournisseurs de soins de santé concernant l’utilisation d’outils de détection de delirium administrés par la famille pour dépister le delirium chez les patients gravement malades. Nous nous sommes aussi intéressés aux obstacles et aux éléments facilitateurs d’une utilisation d’outils de détection du delirium administrés par la famille dans les soins aux patients.

Méthode

Dans le cadre de cette étude qualitative, les fournisseurs de soins intensifs (cinq médecins, six infirmières) et les participants de l’Étude sur la détection familiale du delirium aux soins intensifs (sept anciens patients et des membres de leur famille) ont participé à quatre groupes de discussion dans un hôpital de Calgary, en Alberta.

Résultats

Les principaux thèmes identifiés à la suite de l’analyse thématique de 18 participants étaient les suivants : 1) les perceptions de l’acceptabilité de la détection du delirium administrée par la famille (p. ex., la famille se sent valorisée, l’équipe de soins intensifs (USI) pourrait ne pas utiliser les résultats d’un membre de la famille, l’augmentation de la charge de travail), 2) les considérations concernant la faisabilité (par ex., connaissances insuffisantes, endossement par l’équipe de soins), et 3) les stratégies globales pour appuyer la mise en œuvre de cette modalité dans les soins de routine (p. ex., la valeur de la détection du delirium administrée par la famille pour les patients et les familles est bien comprise dans le contexte clinique, la communication régulière entre la famille et les fournisseurs de soins intensifs, une version électronique de l’outil).

Conclusion

Les patients, les membres de la famille et les fournisseurs de soins de santé qui ont participé aux groupes de discussion ont perçu la participation de la famille à la détection du delirium et l’utilisation d’outils de détection du delirium administrés par la famille au chevet comme étant faisables et utiles pour les soins aux patients et les membres de la famille.

Enregistrement de l’étude

www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03379129); enregistrée le 15 décembre 2017.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Delirium is a common complication of critical illness in patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU)1 and is a strong predictor of worse health outcomes in this already vulnerable patient population. Family members who witness delirium symptoms often experience emotional distress, feelings of anxiety, and helplessness.2,3

In response to the complex burden of delirium for patients and their family members, critical care medicine societies have prioritized prompt facilitation of guideline-concordant care (e.g., early mobility-based rehabilitation, sleep disruption policies, and agitation and sedation protocols) into clinical practice as a first step towards improving patient outcomes.4,5 In addition, routine delirium monitoring using validated tools is recommended for all ICU patients.6 While to date, such monitoring has largely been performed by trained healthcare professionals,7,8 family members at the bedside may be more apt to notice delirium symptoms in the sick patient than a healthcare professional who was previously unknown to the patient.9 In addition, assisting with caregiving tasks like delirium detection at the bedside may offer family members a sense of purpose and serve as a protective mechanism to reduce the stress-related complications of critical illness.10

Recent studies showed that administering two family-administered delirium detection tools (Family Confusion Assessment Method [FAM-CAM] and Sour Seven) among critically ill patients is feasible but has fair but lower diagnostic accuracy than clinical assessments using the Intensive Care Unit Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC) and Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU).11 Nevertheless, perspectives and expectations of family members and the ICU team on delirium detection by the family have not been explored. As such, the current study’s primary objective was to better understand stakeholder perceptions of family participation in delirium detection at the bedside and to describe perceived barriers and facilitators to incorporating this practice into patient care.

Methods

Study design

This study was part of a larger mixed-methods study validating family-administered delirium detection tools at Foothills Medical Centre ICU (Calgary, AB, Canada) between December 2017 and March 2019.9,11 The cross-sectional study included once-daily family-administered delirium detection for up to five days, using the FAM-CAM and Sour Seven questionnaires. The ICU regularly screens for delirium once per shift using the ICDSC12 and a multidisciplinary team discusses delirium daily (as part of the ABCDEF bundle) during rounds, which a recent study reported that 23% of families attended.13 We used a qualitative descriptive approach14 with data collected from focus groups with Canadian critical care medicine physicians, registered nurses (RNs), and patient and family members in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (Electronic Supplemental Material [ESM], eAppendix 1).15,16 The University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board approved this study (Ethics ID: REB16-2060).

Selection and description of participants

We used convenience sampling including patients and family members who participated in the larger study11 and indicated interest in participating in a follow-up focus group (patients: 9.6% [21/218]; family members: 23% [34/147]) (Figure). Patients or their family members were adults (≥18 yr), able to understand English, and able to provide informed consent. We invited patients or their family members using the contact information they provided (e-mail or telephone). Physicians and RNs were sent an e-mail by their direct supervisor to ask if they would like to participate in a focus group; those who were interested contacted the study team directly. Because people in different healthcare roles may have different perspectives on family-administered delirium detection, three distinct focus groups were recruited: previous ICU patients and family members; ICU RNs who provide bedside care that includes routine delirium assessments; and physicians who provide care to ICU patients (ESM, eAppendix 2).

Focus group guide

A multidisciplinary research team (patient partner [C.F.], intensivist [T.S.], RN [K.S.], research coordinator [K.K.], researcher [K.F.] and qualitative research expert [J.P.L.]) created a semi-structured interview guide based on research experience, relevant literature,17,18 and three predetermined categories of interest: 1) use of family-administered delirium detection tools at the bedside, 2) important features (e.g., design, functionality) to be considered in tools used by family members, and 3) barriers and facilitators to implementing family-administered delirium detection tools into routine patient care. Categories of interest and associated questions were presented to a provincial working group of delirium stakeholders (ICU decision makers, clinicians, RNs, and researchers) who had no prior involvement with the research program for feedback and as a measure of quality control. An interview guide was then drafted, and pilot tested on four occasions by way of independent interview with a former ICU patient, family member, RN, and physician. The interview guide was iteratively refined in response to the first three pilot interviews, with no further edits to the guide required after this point (see ESM, eAppendix 3).

Data collection

Prior to each focus group, participants were sent an e-mail containing information about the focus group objectives, the consent form, and copies of the family-administered delirium detection tools we would be discussing (FAM-CAM and Sour Seven Questionnaire)17,18 for their review. Participant consent was obtained by the research team prior to the start of each focus group.

For all focus groups, an observer took notes (K.K.) on non-verbal cues (e.g., head nodding, emotional reactions, key points, or recurring themes) without active participation. All focus groups were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, de-identified, and imported into NVivo-12 (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) for data management.

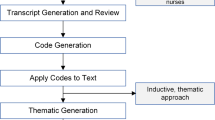

Data analysis

Data analysis incorporated both directed deductive thematic analysis19 using a grounded theory approach, but guided by a catalogue of predetermined objectives (e.g., to understand stakeholder perceptions and opinions of acceptability and feasibility of family-administered delirium detection in the ICU) derived from the parent study.11,20 We used a data-driven inductive approach to coding.21 This approach complemented our research question by allowing our working knowledge of the topic22 to guide the overall structure of focus group discussions, while also permitting themes to emerge directly from the data.23 The coding process included two coders (J.P.L., K.K.) who carefully read all transcripts before coding half the data set to generate initial codes. Coders then switched transcripts so that all were coded in duplicate. Coders searched for themes by collating codes across the data set and met biweekly for two months to refine themes and discuss analysis. Descriptive study reports summarizing major findings of the focus groups were produced in the final analysis meeting. All participants were provided with a copy of the study report to review and comment on as a form of member-checking to ensure accuracy, credibility, and validity.

Results

Twenty-one patients, 34 family members, seven ICU physicians, and 180 ICU RNs were invited to participate through an e-mail invitation. The physician (n = 6, 1 hr) and RN (n = 5, 2 hr) focus groups were moderated by an experienced facilitator (N.Z.). Patient and family member focus groups (n = 4, n = 3, 2 hr each) were moderated by a patient partner (C.F.) with experience planning and facilitating focus groups.

When asked about their perceptions of the level of delirium knowledge the average family member would have when a patient is admitted to ICU, participants across all focus groups unanimously suggested that most family members would likely have a low to moderately low level of pre-existing knowledge (i.e., would score 1-3 on a five-point Likert scale where 0 indicated no delirium knowledge and 5 indicated very knowledgeable). In addition, most patients and family members described learning about the meaning of their family member’s delirium by searching the term online or by reading pamphlets presented to them by the research study team.

Three main themes and associated subthemes related to family-administered delirium detection at the bedside were identified in the data: 1) perceptions of acceptability (i.e., likes, dislikes, and potential implications) of the approach, 2) considerations related to feasibility (i.e., barriers and facilitators related to tool use), and 3) suggested strategies to support implementation into routine patient care (i.e., how to improve use of the tool).

Family-administered delirium detection—perceptions of acceptability

Participants across all focus groups discussed their perceptions of the acceptability of employing family-administered delirium detection tools at the bedside in the ICU (see ESM, eAppendix 4). There was a high level of agreement across ICU providers (RN/MD) and patient and family members that family-administered delirium detection tools have the potential to positively impact the care of sick patients by providing an opportunity for someone who knows the patient better than the healthcare team (family member) to weigh in on changes and subtleties related to the patient’s overall demeanor and wellbeing (e.g., more or less irritable than normal).

“…the family knows the very subtle details about the patient’s personality and level of function far better than anybody who has only been with them for few days or couple of weeks”-ICU physician

In addition, ICU healthcare providers, patients, and family members suggested that family members may derive feelings of personal value and self-worth from being actively involved in care of the sick patient.

“If [family-administered delirium detection] were used to disseminate information to the caregiving team, I would think it…I would feel valued” -Family member

“Because I figured I’m not a physician or a nurse, I don’t have a role here…but you feel like maybe if you had these tools, that could have been a role in rounds, to let me give [the ICU care team] an update on delirium.” -Family member

Finally, ICU providers noted that involvement in ICU care could serve as a protective mechanism against post-ICU mental health issues in family members, while family members described that the increased knowledge of delirium they gained through participation in the study made them more likely to recognize the signs and symptoms of delirium in their family member and understand that symptoms would eventually subside.

“… families of patients who are delirious have adverse mental health effects themselves… something like [family-administered delirium detection] could help.” -ICU physician

Intensive care unit providers expressed some concerns about the use of family-administered delirium detection at the bedside. Intensive care unit RNs highlighted that involving families in patient care may intensify their workload (since RNs would likely be receiving added information about delirium from the families). This concern was echoed by physicians who questioned whether teams would have the capacity to meaningfully communicate with family members about the information present in the detection tool. In addition, some physicians suggested that participation in delirium detection may be anxiety-provoking for certain families and that the currently used ICDSC24 may be just as effective as family-administered delirium detection without the potential for added complications. Finally, one family member expressed discomfort and hesitation in answering the questions posed in the delirium detection tools when the patient is sedated, intubated, or non-communicative.

“…unsure of how to answer the questions because I think they were too detailed for our situation because he was incommunicative, intubated, sedated… “ -Family member

Family-administered delirium detection—considerations regarding feasibility

During the focus groups, participants discussed the feasibility of using family-administered delirium detection tools at the bedside. Top barriers described by physicians were insufficient knowledge on the part of the healthcare team regarding the tool’s purpose, and uncertainty about what to do with the results of family-administered delirium detection tools. Physicians also worried that if scores were misinterpreted by family members (e.g., probability of presence of delirium vs severity of condition), uptake by clinicians could be negatively impacted. Similarly, ICU RNs highlighted healthcare team buy-in (i.e., acceptance of the tool or willingness to actively support its use), lack of training (e.g., easy to understand explanations of how to use and interpret the results of the tool) for all stakeholders (ICU team, family members), and the extra time it would take to educate stakeholders in preparation for implementation of the practice, as top obstacles to feasibility. Top barriers described by patient and family members included staff seeing the tool as a burden or as non-important (e.g., staff exhibiting signs of a judgemental attitude when submitting the form), family members who speak English as a second language (i.e., difficult to translate an already complex topic into a different language), and only having options of yes/no answers when a preferred response may be “not applicable” or “don’t know.” In addition, a small number of patient and family members described the number of forms involved in the process as overwhelming and the lack of information they received back from the healthcare team (i.e., acknowledgment or interpretation of the score) as disheartening or frustrating.

“If the staff handling it had any kind of judgemental attitude, that would be bad.” -Family member

In each focus group, participants described specific facilitators that they perceived would assist stakeholders to overcome identified barriers. Of note, physicians highlighted education, group terms of reference regarding aspects of patient care the tool would inform (i.e., diagnosis, prognosis and/or treatment), and an accessible platform of administration (i.e., electronic) as key facilitators. Intensive care unit RNs emphasized the use of a simple tool with plain language, mandatory training for healthcare teams, and local champions who are early adopters of the tool (i.e., to promote its use). Finally, patients and families described education related to delirium and an explanation of how to use the tool as top facilitators. They also mentioned clear and specific questions and a predetermined feedback loop to ensure that they have an opportunity to learn about what the results of the tool mean (and any clinical actions taken in response) as top facilitators.

“I would want…whoever’s in charge of my [family member] to know my responses because they may totally disagree or go, ‘Oh, I hadn’t notice that today’…we could have a discussion about it.” -Family member

Strategies to support implementation of family-administered delirium detection into routine patient care

Participants were largely in favour of working towards identifying overarching solutions to facilitate the implementation of family-administered delirium detection into routine patient care. Top reasons given for this perspective included: 1) family-administered delirium detection may be a means to mature the way delirium is considered in the clinical context (physician focus group), 2) that it may give family members a sense of purpose and position their voice as an important part of the care team (RN focus group), and 3) that clinicians will have more information to work with to treat their patients (patient/family focus group). When asked to describe overarching strategies that would help to facilitate and sustain this process (distinctly different from conversations surrounding barriers, e.g., insufficient knowledge, and facilitators, e.g., targeted education, to tool use that were unique to each stakeholder group), we identified three main strategies across all focus groups: 1) the value of family-administered delirium detection for patients and families is well understood in the clinical context (e.g., outlined in educational materials that are given to all stakeholders and/or are posted in the unit); 2) communication between the family and ICU healthcare provider about the tool, meaning of the results, and plan is predetermined and streamlined (e.g., offer daily rounds as an ideal time point to anchor this communicative exchange); 3) an electronic version of the tool is offered whenever possible (i.e., to cut down on overwhelming and unnecessary paperwork). In addition, an important strategy provided by all ICU providers that was not present in the patient and family focus groups was mandatory training for all members of the healthcare team to bolster understanding and buy-in.

Discussion

After showing feasibility, acceptability, and validity of two family-administered delirium detection tools in the ICU setting,9,11,25,26 we conducted a focus group study to explore perceptions of family participation in delirium detection among critical care stakeholders. Our findings indicated support for the engagement of family members at the bedside. In the context of delirium detection, this support largely hinged on the notion that family participation in care has the potential to positively impact patient health outcomes (e.g., earlier delirium detection and management using non-pharmacologic strategies) and the experiences of family members (e.g., by granting them voice and purpose in the clinical process).

Previous research has shown that family participation in patient care is largely acceptable to patients, family members, and healthcare providers in the ICU.27,28,29 For example, an observational study exploring the perceptions and opinions of ICU stakeholders found that most families (97%), patients (77%), and healthcare providers (physicians: 100%; RNs: 90%) were supportive of family participation in care at the bedside and believed that it may have reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression and increased family satisfaction.28 This is like the current study, where healthcare providers felt family participation in ICU care could protect families from post-ICU mental health issues. Moreover, family members’ increase in delirium knowledge and participation in ICU care made them feel valued, which may increase family satisfaction. Previous research has shown that family members of critically ill patients are willing to assist with non-pharmacologic delirium prevention activities and that families feel their presence helped patients through symptoms of delirium).30 These findings are like the current study where families felt family-administered delirium detection provided clinicians with more information to treat their patients. Research surveying physicians’ use of the ABCDEF bundle reported that families are involved in delirium prevention activities 67% of the time, and that when families participate in care there is higher prevalence of interventions to reduce and treat delirium.31 Finally, a recent systematic review reported that patient- and family-centred care increased family satisfaction, increased understanding of their loved ones’ medical status, and reduced negative mental health outcomes in the patient and their family.32

Though family participation in patient care has been identified as a priority,33 several barriers need to be considered prior to evaluating this strategy as a way to improve patient- and family-centred outcomes. For example, previous research on open ICU visitation showed that increased family presence can disrupt RNs’ workflow and delivery of care.34 These findings align with results from the current study, which identified a similar concern in RNs and physicians. Family presence at the bedside may also have negative implications for patients experiencing delirium. For example, a qualitative analysis on pain, agitation, and delirium management reported that RNs perceived family presence to agitate patients or prevent patients from resting properly.35 Registered nurses and physicians did not express this concern in the current study. Moreover, RNs described that family-administered delirium has the potential to meaningfully engage families at the bedside and that their increased understanding of delirium may be helpful. A recent randomized-controlled trial with 1,685 patients reported that increased family visitation did not increase the incidence of delirium during their ICU stay.36

Educating families on pain, agitation, and delirium and including families in multidisciplinary team discussions was identified as an important facilitator to improving the quality of patient care.35 The provision of indirect education, through leaflets or informational videos, has also been identified as a strategy to reduce RN-led education on patient care activities, thus minimizing additional burden that would otherwise be placed on nursing staff.37,38,39 During the Family ICU Delirium Detection Study, each admitted patient and their family received a pamphlet on symptoms of delirium, delirium risk factors, and prevention and management using non-pharmacologic strategies. Nevertheless, as indicated by families, patients, and healthcare providers, these approaches should include communication between the family member and ICU healthcare providers to provide clinical context during delirium-related conversations. Registered nurses and physicians indicated that family-administered delirium detection may be anxiety-provoking and may add more burden to a family who may be overwhelmed. Developing a standardized third-party approach to education provides families with space to engage or decline participation based on (potentially shifting) desires for the clinical interaction. This is important because as with all family engagement strategies, family-administered delirium detection may not be desired by all (including patients). Future studies evaluating family-administered delirium detection as a strategy to improve patient- and family-centred outcomes should be co-designed with key stakeholder groups (e.g., RNs, physicians, patients, and families) to ensure acceptability and appropriateness of the study protocol. These studies should explore whether providing education on the FAM-CAM and Sour Seven improves a family member’s confidence and ability to detect delirium using these family-administered tools.

The strengths of this study include that focus group guides were co-designed by patients, researchers, and clinicians and tested in a pilot study. The patient and family focus groups were moderated by a patient partner. There are limitations to consider when interpreting the findings of our study. First, this is a single-centre qualitative study including 18 participants, which has implications for the transferability of results. It is possible that additional focus groups (even within a single centre) would have yielded additional themes. Second, the number of participants included in this study was dependent on the agreement of participants in the parent study to participate in a follow-up focus group. Third, it is possible that patient or family caregiver’s perspectives were missed as the focus groups included patients and family members together in one session. Fourth, our sampling frame was small and, as such, we were unable to achieve adequate representation of urban/rural, sex, gender, education, and socioeconomic status. Finally, it is possible that important perspectives were missed, given that participants may have been motivated to participate as a result of mostly positive or mostly negative experiences.40 Nevertheless, this study offers important insight into stakeholder perceptions of appropriateness related to the conduct of family-administered delirium detection as well as barriers and facilitators associated with engaging family members in delirium detection at the bedside. The focus groups provided an opportunity for facilitated group discussion, often creating a synergy of ideas for improving family-administered delirium detection.

Conclusion

Patients, family members, and healthcare providers who participated in the focus groups perceived family-administered delirium detection as feasible and of value to patient care and family member coping. Actively involving family members in delirium detection at the bedside may improve outcomes and experiences for both patients and family members. Nevertheless, several identified perceived facilitators and barriers need to be addressed before family-administered delirium detection is implemented into routine patient care. Given the small sample size, this work is hypothesis-generating and further studies with larger and broader samples are warranted.

References

Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA 2001; 286: 2703-10.

Bull MJ. Delirium in older adults attending adult day care and family caregiver distress. Int J Older People Nurs 2011; 6: 85-92.

Schmitt EM, Gallagher J, Albuquerque A, et al. Perspectives on the delirium experience and its burden: common themes among older patients, their family caregivers, and nurses. Gerontologist 2019; 59: 327-37.

Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Gelinas C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption in adult patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med 2018; 46: e825-73.

Davidson JE, Harvey MA, Bemis-Dougherty A, Smith JM, Hopkins RO. Implementation of the pain, agitation, and delirium clinical practice guidelines and promoting patient mobility to prevent post-intensive care syndrome. Crit Care Med 2013; 41(9 Suppl 1): S136-45.

Marra A, Pandharipande PP, Patel MB. Intensive care unit delirium and intensive care unit-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Surg Clin North Am 2017; 97: 1215-35.

Hargrave A, Bastiaens J, Bourgeois JA, et al. Validation of a nurse-based delirium-screening tool for hospitalized patients. Psychosomatics 2017; 58: 594-603.

Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2013; 41: 263-306.

Krewulak KD, Sept BG, Stelfox HT, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of family administration of delirium detection tools in the intensive care unit: a patient-oriented pilot study. CMAJ Open 2019; 7: E294-9.

Davidson JE, Daly BJ, Agan D, Brady NR, Higgins PA. Facilitated sensemaking: a feasibility study for the provision of a family support program in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Nurs Q 2010; 33: 177-89.

Fiest KM, Krewulak KD, Ely EW, et al. Partnering with family members to detect delirium in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2020; 48: 954-61.

Bergeron N, Dubois MJ, Dumont M, Dial S, Skrobik Y. Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist: evaluation of a new screening tool. Intensive Care Med 2001; 27: 859-64.

Au SS, Roze des Ordons AL, Amir Ali A, Soo A, Stelfox HT. Communication with patients’ families in the intensive care unit: a point prevalence study. J Crit Care 2019; 54: 235-8.

Kim H, Sefcik JS, Bradway C. Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: a systematic review. Res Nurs Health 2017; 40: 23-42.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007; 19: 349-57.

Smithson J. Using and analysing focus groups: Limitations and possibilities. Int J Soc Res 2000; 3: 103-19.

Shulman RW, Kalra S, Jiang JZ. Validation of the Sour Seven Questionnaire for screening delirium in hospitalized seniors by informal caregivers and untrained nurses. BMC Geriatr 2016. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0217-2.

Steis MR, Evans L, Hirschman KB, et al. Screening for delirium using family caregivers: convergent validity of the Family Confusion Assessment Method and interviewer-rated Confusion Assessment Method. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60: 2121-6.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 77-101.

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005; 15: 1277-88.

Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods 2006; 5: 80-92.

Oxenboll-Collet M, Egerod I, Christensen V, Jensen J, Thomsen T. Nurses’ and physicians’ perceptions of Confusion Assessment Method for the intensive care unit for delirium detection: focus group study. Nurs Crit Care 2018; 23: 16-22.

Sandelowski M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health 2010; 33: 77-84.

Ouimet S, Riker R, Bergeron N, Cossette M, Kavanagh B, Skrobik Y. Subsyndromal delirium in the ICU: evidence for a disease spectrum. Intensive Care Med 2007; 33: 1007-13.

Fiest KM, McIntosh CJ, Demiantschuk D, Parsons Leigh J, Stelfox HT. Translating evidence to patient care through caregivers: a systematic review of caregiver-mediated interventions. BMC Med 2018. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1097-4.

Gagliardi AR, Legare F, Brouwers MC, Webster F, Badley E, Straus S. Patient-mediated knowledge translation (PKT) interventions for clinical encounters: a systematic review. Implement Sci 2016. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0389-3.

Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, et al. Family participation in care to the critically ill: opinions of families and staff. Intensive Care Med 2003; 29: 1498-504.

Garrouste-Orgeas M, Willems V, Timsit JF, et al. Opinions of families, staff, and patients about family participation in care in intensive care units. J Crit Care 2010; 25: 634-40.

Wong P, Redley B, Digby R, Correya A, Bucknall T. Families’ perspectives of participation in patient care in an adult intensive care unit: a qualitative study. Aust Crit Care 2020; 33: 317-25.

Smithburger PL, Korenoski AS, Alexander SA, Kane-Gill SL. Perceptions of families of intensive care unit patients regarding involvement in delirium-prevention activities: a qualitative study. Crit Care Nurse 2017; 37: e1-9.

Morandi A, Piva S, Ely EW, et al. Worldwide survey of the “assessing pain, both spontaneous awakening and breathing trials, choice of drugs, delirium monitoring/management, early exercise/mobility, and family empowerment” (ABCDEF) bundle. Crit Care Med 2017; 45: e1111-22.

Goldfarb MJ, Bibas L, Bartlett V, Jones H, Khan N. Outcomes of patient- and family-centered care interventions in the ICU: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 2017; 45: 1751-61.

Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, et al. Guidelines for family-centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Crit Care Med 2017; 45: 103-28.

Monroe M, Wofford L. Open visitation and nurse job satisfaction: an integrative review. J Clin Nurs 2017; 26: 4868-76.

Tsang JL, Ross K, Miller F, et al. Qualitative descriptive study to explore nurses’ perceptions and experience on pain, agitation and delirium management in a community intensive care unit. BMJ Open 2019. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024328.

Rosa RG, Falavigna M, da Silva DB, et al. Effect of flexible family visitation on delirium among patients in the intensive care unit: the ICU visits randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019; 322: 216-28.

Nolen KB, Warren NA. Meeting the needs of family members of ICU patients. Crit Care Nurs Q 2014; 37: 393-406.

Soury-Lavergne A, Hauchard I, Dray S, et al. Survey of caregiver opinions on the practicalities of family-centred care in intensive care units. J Clin Nurs 2012; 21: 1060-7.

Riley BH, White J, Graham S, Alexandrov A. Traditional/restrictive vs patient-centered intensive care unit visitation: perceptions of patients’ family members, physicians, and nurses. Am J Crit Care 2014; 23: 316-24.

Dotolo D, Nielsen EL, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA. Strategies for enhancing family participation in research in the ICU: findings from a qualitative study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017; 54(226-30): e1.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the funding agencies who supported this work (MSI Foundation, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canadian Frailty Network [Technology Evaluation in the Elderly Network] which is supported by the Government of Canada through the Networks of Centres of Excellence program, and Alberta Health Services, all to KMF). Thank you to Bonnie Sept and Israt Yasmeen who assisted with participant recruitment.

Author contributions

All authors (Jeanna Parsons Leigh, Karla D. Krewulak, Nubia Zepeda, Christian E. Farrier, Krista L. Spence, Judy E. Davidson, Henry T. Stelfox, and Kirsten M. Fiest) made substantial contributions to study conception and design, and the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; Jeanna Parsons Leigh drafted the manuscript; all authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content.

Disclosures

None.

Funding statement

This work was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grant and Canadian Frailty Network (Technology Evaluation in the Elderly Network), which is supported by the Government of Canada through the Networks of Centres of Excellence program (to KMF). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Sangeeta Mehta, Associate Editor, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Parsons Leigh, J., Krewulak, K.D., Zepeda, N. et al. Patients, family members and providers perceive family-administered delirium detection tools in the adult ICU as feasible and of value to patient care and family member coping: a qualitative focus group study. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 68, 358–366 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-020-01866-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-020-01866-3