Abstract

Background

Delirium is frightening for people experiencing it and their carers, and it is the most common hospital-acquired complication worldwide. Delirium is associated with higher rates of morbidity, mortality, residential care home admission, dementia, and carer stress and burden, yet strategies to embed the prevention and management of delirium as part of standard hospital care remain challenging. Carers are well placed to recognize subtle changes indicative of delirium, and partner with nurses in the prevention and management of delirium.

Objective

To evaluate a Prevention & Early Delirium Identification Carer Toolkit (PREDICT), to support partnerships between carers and nurses to prevent and manage delirium.

Design

A pre–post-test intervention and observation study.

Main Measures

Changes in carer knowledge of delirium; beliefs about their role in partnering with nurses and intended and actual use of PREDICT; carer burden and psychological distress. Secondary measures were rates of delirium.

Participants

Participants were carers of Indigenous patients aged 45 years and older and non-Indigenous patients aged 65 years and older.

Intervention

Nurses implemented PREDICT, with a view to provide carers with information about delirium and strategies to address caregiving stress and burden.

Key Results

Participants included 25 carers (43% response rate) (n = 17, 68% female) aged 29–88 (M = 65, SD = 17.7 years). Carer delirium knowledge increased significantly from pre-to-post intervention (p = < .001; CI 2.07–4.73). Carers’ intent and actual use of PREDICT was (n = 18, 72%; and n = 17, 68%). Carer burden and psychological distress did not significantly change. The incidence of delirium in the intervention ward although not significant, decreased, indicating opportunity for scaling up.

Conclusion

The prevention and management of delirium are imperative for safe and quality care for patients, carers, and staff. Further comprehensive and in-depth research is required to better understand underlying mechanisms of change and explore facets of nursing practice influenced by this innovative approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Delirium, the most common hospital-acquired complication worldwide, is characterized by shifting attention, incoherence, disorientation, and impaired cognition.1 It is a frightening experience for the person affected, and their sudden change in behavior and/or emotions can impact family carers’ burden and psychological distress.1,2,3 The global rise in ageing populations is expected to exacerbate the impact of delirium in healthcare settings, leading to increased rates of hospital-acquired complications (e.g., falls), delayed discharge, re-admissions, dementia, residential aged care admissions, death, and greater caregiving responsibilities for families.4 Therefore, the prevention, identification, and early management of delirium are imperative in the provision of safe, high-quality care for both the patient and their family.

The healthcare team, including nurses, are responsible for the initial and ongoing assessment, management, and safety of patients at risk of delirium across hospital settings; however, prevention strategies and risk screening are not consistently practiced, and understanding of and recognition of delirium is poor.5,6,7 Reasons for undiagnosed delirium include language barriers, fluctuation of symptoms during the day, a lack of routine screening and assessment, lack of resources, competing clinical priorities, and organization culture.5,8,9,10,11,12,13 These are compounded by a lack of knowledge of the patient’s prior day-to-day level of functioning by the healthcare team.14

Rapid deterioration due to delirium begins with subtle changes that are best recognized by family or close ones (referred to as carers here on).15 Carers can provide not only a valuable cognitive anchor point but also comforting reassurance, and if supported by clinicians, implement preventative non-pharmacological interventions.14,16,17,18,19,20,21 Interventions implemented with carers to address delirium have been found to improve nurse and carer delirium knowledge,20 reduce carer psychological distress,18,22 and length of hospital stay.18,23,24 However, innovative interventions to support partnerships with carers in the prevention and management of delirium in the hospitalized older patient are needed.25,26

Aim

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate a Prevention & Early Delirium Identification Carer Toolkit (PREDICT) to support partnerships between carers and nurses to prevent and manage delirium. Specifically, the study aimed to evaluate changes in the carer:

-

•Knowledge of delirium prevention and management

-

•Beliefs about their role in partnering in delirium prevention and management

-

•Actual and intended use of PREDICT

-

•Levels of burden and psychological distress

A secondary aim of this study was to evaluate changes in the incidence of delirium. We hypothesized that the involvement of nurses would improve their understanding of delirium and lead to changes in nursing practice and delirium incidence rates.

METHOD AND MATERIALS

Design

A pre–post-test intervention study was conducted on a medical ward in an Australian regional hospital with data collected during admission (pre-intervention) and 4–6 weeks post-discharge (post-intervention). A further observational study to address the secondary aim examined the incidence of delirium during the intervention period compared to the same period 12 months prior.

The Intervention (PREDICT)

Acknowledging and valuing the insight and lived experience, a model of care utilizing a Prevention & Early Delirium Identification Carer Toolkit (PREDICT) was codesigned and validated by carers whose family members had been hospitalized and for some had experienced delirium, consumers, and healthcare professionals working in the acute care setting.27 PREDICT, available on a digital platform and accessed via QR code, included short videos and information on delirium preventive strategies, risk factors, and non-pharmacological interventions to reorientate older adults who experience delirium. To enable carers to express and communicate their concerns about the person being cared for, an interactive psychometrically tested delirium screening questionnaire suitable for informal or untrained carers was also included.14 To support carer well-being and address burden and psychological distress, PREDICT also includes information and links to carer resources such as counselling and social prescribing programs (social service programs that provide activities to improve health and well-being).27 PREDICT was also made available in hard copy.

Participants

Participants were carers of Indigenous patients aged 45 years and older and non-Indigenous patients aged 65 years and older. The lower age range for Indigenous patients was set because people who identify as Indigenous Australians are more likely to develop serious medical conditions earlier in life and have a lower life expectancy than non-Indigenous Australians28 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023).

Eligibility

The carer was eligible to receive PREDICT if visiting at the patient’s bedside daily during hospitalization for ≥ 2 days and could communicate in English or with an interpreter. The carer was not eligible to participate if the patient’s hospital stay was less than 48 h, and the patient was receiving end-of-life care or had a diagnosis of advanced dementia and was unable to communicate or interact.

Procedure

Prior to the implementation of PREDICT (September 2022 to February 2023), nurses received a delirium education session and orientation to PREDICT, and during the study nurses received ongoing weekly briefings from the lead ward nurse for dementia and delirium. This regular communication was to ensure the nursing staff were equipped to answer questions the carer may have regarding PREDICT, the delirium screening questionnaire, and the study evaluation. Posters promoting PREDICT and the study evaluation were placed in strategic areas around the ward, with contact information for further enquiries.

The admitting nurse offered eligible carers access to PREDICT. Carers were advised that they were not required to participate in the study evaluation (that is, complete the study survey) to receive and engage with PREDICT.

Nursing staff were encouraged to support all carers to use PREDICT daily, including the delirium screening questionnaire.14 Carers were not offered incentives to participate.

Data Collection

Participating carers were invited to complete an anonymous survey online using Qualtrics,29 or in a paper-based format, at admission (pre-intervention) and 4–6 weeks post-discharge (post-intervention). Pre- and post-intervention surveys were matched using an anonymous participant-generated code (the last 4 digits of participants’ phone numbers, and first initial of their mother’s name). For carers completing a paper-based survey, a secure box was placed at the nurses’ station for surveys returned at admission and a reply-paid envelope for surveys returned at 4–6 weeks follow-up. The incidence of delirium (using the standard unit of measurement of utilization—cases per 1000 occupied bed days (OBDs)) during the intervention period (T2) was compared to the same period 12 months prior (T1).

Measures

The following measures were combined into the online survey as a continuous tool.

Demographics

Carer demographic items included age, gender, whether they identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, length of time as a carer, their relationship with the person they cared for, and whether they lived together, as well as the age and gender of the person they cared for.

Caregiver Delirium Knowledge Questionnaire (CDKQ)14

The CDKQ is a validated measure of carer knowledge of delirium risk factors, symptoms, and appropriate actions with good internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.76).22 Nineteen true/false items across three subscales include Risk (10 items, e.g., dehydration), Symptoms (5 items, e.g., increasing confusion over several days), and Actions (4 items, e.g., immediately calling a doctor). Total and subscale scores comprise the sum of correct items where higher scores indicate greater knowledge.

Beliefs About Carers’ Role in Partnering in Delirium Prevention and Management

A single item question was asked, rated “yes” or “no.”

“Do you think that carers should be incorporated into delirium identification and management?”

Carers’ Intended and Actual use of PREDICT, Including the Delirium Screening Questionnaire

Two questions were asked, rated “yes” or “no.”

“Do you intend to use/ Did you use the Delirium Toolkit?”

“Do you intend to use/ Did you use the delirium screening questionnaire?”

Caregiver Delirium Burden Scale (DEL-B-C)30

The DEL-B-C is a validated 16-item measure of the burden experienced by carers; Cronbach’s α = 0.82.31 Total scores range from 0 to 40 with higher scores indicating greater burden.

Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10)32

The K10 is a widely used and validated measure of psychological distress; Cronbach’s α = 0.93.32,33 Total scores range from 10 to 50 with higher scores indicating greater psychological distress.

Incidence of Delirium

Routinely collected hospital data was accessed to determine delirium incidence. Data was calculated using cases per 1000 OBDs which were compared from September 2021 to February 2022 (T1) and during the intervention period September 2022–February 2023 (T2).

Ethical Conduct

Ethical approval was provided by [removed for blinding].

Analysis

Data were entered using Qualtrics survey software,29 downloaded and cleaned, checked, and analyzed in SPSS 2734 and OpenEpi35 analysis software. Summary and descriptive statistics were produced including frequencies, totals, and means of participant demographics and study outcome variables. Significance level was set at alpha (α) = 0.05. Normality was established by visual inspection of histograms, skew and kurtosis, and Shapiro–Wilk (as n < 50) tests of normality.36 Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated as estimates of clinical significance where 0.2 indicates a small effect size, 0.5 moderate, and 0.8 large.37 Normally distributed data were assessed for change from admission to post-discharge using paired t-tests (CDKQ, DEL-B-C, K10). Non-parametric data were assessed for change using related-samples McNemar change tests for dichotomous dependent variables (beliefs about partnering, satisfaction with care). Relationships between demographics and outcome variables (years as a carer versus intended and actual use of PREDICT) were assessed using independent-samples Mann–Whitney U tests. Missing values were handled as follows: frequency data (demographics, beliefs about partnering and use of PREDICT) were unchanged and were reported in raw form; missing CDKQ items were scored as incorrect; missing DEL-B-C items were scored as though carers had not experienced the relevant burden; and no K10 items were missing. Change in delirium incidence was analyzed by calculating an incidence rate ratio (IRR)—that is, comparing incidence at T1 and T2, wherein an IRR of 1 (or 95% CI that includes 1) indicates equal rates of delirium and thus a non-significant change; Z (standard) scores and p values are also presented for IRRs.38,39

RESULTS

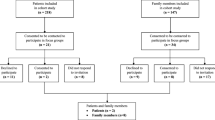

Participants

PREDICT was provided to a total of 56 carers, of whom 25 carers (43%) provided pre- and post-intervention data. Carers were primarily females (n = 17, 68%) with an average age of 65 years (SD = 17.7) providing care for their partner (n = 15, 60%). The majority of carers (n = 17, 68%) lived with the patient prior to admission. A total of seven carers (28%) reported the patient was diagnosed with delirium; see Table 1 for demographics.

Carer Delirium Knowledge

Carer delirium knowledge (CDKQ)22 increased significantly from admission (M = 8.7, SD = 4.62) to post-discharge (M = 12.1, SD = 5.43). Scores increased by an average of 3.4 (SE = 0.65, 95% CI [2.07, 4.73]; paired t(24) = 5.27, p = < 0.001, d = 1.1). This very large effect size (d) indicates a meaningful, clinically significant improvement in delirium knowledge.37

Beliefs about Partnering in Delirium Prevention and Management

During admission, the majority of carers (n = 18, 72%) believed carers should be incorporated into delirium identification and management, which increased to 24 (96%) post-discharge. A related-samples McNemar change test indicated this was a significant increase (p < 0.001).

Carers’ Intended and Actual Use of PREDICT

At admission, most carers intended to use PREDICT (n = 18, 72%), and at post-discharge nearly all carers with positive intentions reported they had used PREDICT (n = 17, 68%). Similarly, at admission, most carers intended to use the delirium screening questionnaire (n = 17, 68%) and at post-discharge most reported they had used it (n = 15, 60%), reflecting an effective intention-behavior link with minimal gap;40 see Table 2.

Intended and actual use of PREDICT was associated with total time as a carer, where participants who had been carers for longer were significantly more likely to report intention to use PREDICT (Mann–Whitney U = 93.5, p = 0.003) and the delirium screening questionnaire (U = 90.0, p < 0.001) weekly, and actual weekly use PREDICT (U = 69.0, p = 0.039) and delirium screening questionnaire (U = 77.0, p = 0.011).

Carer Burden and Distress

Carer burden (DEL-B-C)31 and distress (K10)32 did not change significantly from admission to post-discharge (p > 0.05). K10 scores were consistently high with carers reporting moderate–high levels of psychological distress at both timepoints41; see Table 3.

Incidence of Delirium

The incidence of delirium on the medical ward was 16.6 cases per 1000 OBDs for 2022/2023, compared to 27.1 cases per 1000 OBDs in the 2021/2022 matched period. The incident risk ratio (IRR) for delirium during the period PREDICT was introduced, compared to the same period 12 months prior which was 0.61 [95%CI 0.33, 1.13]. The associated z-value was 1.59 with a p-value of 0.056 approaching significance. Given the impacts of COVID-19 on healthcare utilization, for contextual comparison points data was also pulled for the whole of hospital, the whole of health district, and the state for the same time periods, which can be seen in Table 4. No other dataset showed any changes in OBD nearing significance, demonstrating promise of association related to the intervention rather than external factors.

DISCUSSION

There is increasing attention on the importance of the prevention and early management of delirium because of the deleterious effect on older patients’ and carers’ health and well-being.2,3,30 This study evaluated the introduction of a model of care utilizing PREDICT, an interactive toolkit designed to support partnerships with carers and nurses in the prevention and management of delirium. The results of this study while only indicative, are promising, highlighting a partnership approach with carers may impact delirium prevention and management.

Several recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses highlight the importance of carer involvement in delirium management42 and the efficacy of education;11,18 however, many key studies omit the carer perspective.15 While most carers in this study significantly increased their knowledge of delirium, we were also able to demonstrate that they saw a clear role for their ongoing involvement in preventing and managing delirium, particularly carers who had been caring for a longer time. This is important because it presents opportunities for improved long-term patient outcomes as the carer is likely to continue to monitor delirium risk following discharge. These findings respond directly to the expectations of carer involvement in care decisions and delivery, as demonstrated by delirium guidelines and standards worldwide.43,44,45

Despite increases in delirium knowledge and the utilization of acquired learnings, carers’ moderately high levels of psychological distress and burden did not significantly improve, contrasting with other studies.11,22 While this finding could be due to differences in characteristics of sample populations, it is consistent with studies reporting carers were often highly distressed when the person they were caring for experienced delirium or was at risk of delirium.46,47 Perception of burden is multifaceted and changes over time, raising questions as to whether equity measurements, such as social needs and barriers to care, such as transportation, food insecurity, and housing, are more relevant outcome indicators of burden for carers.48 While the focus on partnering with carers in our study maximizes the opportunity for enhanced communication and collaboration between carers and nurses, further research is required to elicit the impact of psychological distress and burden in the management of delirium.30,49 Where health inequities impact vulnerable groups including LGBTQ + and Indigenous communities,50 further research is required to enable carers to highlight their well-being and support needs.

Finally, in relation to our secondary aim, our findings indicate the potential of partnering with carers in delirium prevention and the broad promotion of PREDICT for reducing the incidence of delirium. Given change in the incidence of delirium was not seen elsewhere in the hospital, local health district, or state figures, it is reasonable to hypothesize that PREDICT might have had a ripple effect at the ward level and improved nurses’ delirium prevention practice. Combined with the pre–post-intervention results, there appears to be merit in proceeding to a randomized controlled trial to further validate and understand this model of care and PREDICT’s broader impact.

When deploying this toolkit in additional facilities, it would be of benefit to specifically explore changes in nurse delirium knowledge levels and self-rated confidence in detecting delirium. This would enable improved measurement of the program’s impact on nurses’ understanding and competence in managing delirium cases. It would also be of benefit to include qualitative interviews to better understand how consciously or unconsciously the program may have influenced their practice, altered perceptions of patient interactions, and transformed their overall approach to care, providing a deeper understanding of any mechanisms of change. Finally, future studies could examine any changes to the way in which nurses work when acting in the role of partner in care, including if there are any changes in shared vigilance, improved communication with carers, or changes in intervention strategies. Understanding any mechanisms of change would be crucial for refining program design and understanding its impact.

Study Limitations

A limitation of this study lies in the small sample size and its location in a single medical ward in an Australian regional hospital. This study did not calculate average length of stay; however, older persons’ hospital service utilization in Australia is reported to average 7.1 days.51 A further limitation was that PREDICT was validated with carers in the community27 but not an inpatient setting. Finally, PREDICT is limited to those patients who have carers visit at the bedside. While carers are not always at the bedside 24/7, the provision of PREDICT to carers upon admission will support any non-face to face communication between healthcare professionals and carers about the cognitive status of the patient. Future rigorous research as to whether partnering with carers in the prevention of delirium using PREDICT can reduce the incidence of delirium will be an important next step.

CONCLUSION

This study focused on engaging and supporting carers as partners in the prevention and management of delirium. While this study presents encouraging preliminary results, more extensive research is required seeking to better understand underlying mechanisms of change and exploring additional facets of nursing practice influenced by this innovative approach.

Data Availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author (Christina Aggar).

References

Fong TG, Racine AM, Fick DM, Tabloski P, Gou Y, Schmitt EM, et al. The Caregiver Burden of Delirium in Older Adults With Alzheimer Disease and Related Disorders. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2019;67(12):2587-92.

Krewulak KD, Bull MJ, Wesley Ely E, Davidson JE, Stelfox HT, Fiest KM. Effectiveness of an intensive care unit family education intervention on delirium knowledge: a pre-test post-test quasi-experimental study. Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia. 2020;67(12):1761-74.

Rosgen BK, Krewulak KD, Davidson JE, Ely EW, Stelfox HT, Fiest KM. Associations between caregiver-detected delirium and symptoms of depression and anxiety in family caregivers of critically ill patients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):187-.

Pereira JVB, Aung Thein MZ, Nitchingham A, Caplan GA. Delirium in older adults is associated with development of new dementia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2021;36(7):993-1003.

Inouye S, K, Westendorp R, GJ, Saczynski J, S. Delirium in elderly people. The lancet. 2014;383(9920):911-22.

Kumbun G, Treml J, Moseley A, Reid J, Furmedge D, Mohammedseid-Nurhussien A, et al. Delirium is prevalent in older hospital inpatients and associated with adverse outcomes: results of a prospective multi-centre study on World Delirium Awareness Day. BMC medicine. 2019;17(1):229-.

Lange PW, Lamanna M, Watson R, Maier AB. Undiagnosed delirium is frequent and difficult to predict: Results from a prevalence survey of a tertiary hospital. Journal of clinical nursing. 2019;28(13-14):2537-42.

Ragheb J, Norcott A, Benn L, Shah N, McKinney A, Min L, et al. Barriers to delirium screening and management during hospital admission: a qualitative analysis of inpatient nursing perspectives. BMC Health Services Research. 2023;23(1):712.

Ahmed S, Leurent B, Sampson EL. Risk factors for incident delirium among older people in acute hospital medical units: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age and ageing. 2014;43(3):326-33.

Hughes CG, Hayhurst CJ, Pandharipande PP, Shotwell MS, Feng X, Wilson JE, et al. Association of Delirium during Critical Illness With Mortality: Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2021;133(5):1152-61.

Lee J, Yeom I, Yoo S, Hong S. Educational intervention for family caregivers of older adults with delirium: An integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2023;32(19-20):6987–97.

Salluh JIF, Wang H, Schneider EB, Nagaraja N, Yenokyan G, Damluji A, et al. Outcome of delirium in critically ill patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical Research ed). 2015;350:h2538-h.

Travers C, Byrne GJ, Pachana NA, Klein K, Gray L. Delirium in Australian hospitals: a prospective study. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research. 2013;2013:284780.

Shulman RW, Kalra S, Jiang JZ. Validation of the Sour Seven Questionnaire for screening delirium in hospitalized seniors by informal caregivers and untrained nurses. BMC Geriatrics. 2016;16:44.

Aggar C, Craswell A, Bail K, Compton R, Hughes M, Sorwar G, et al. Partnering with carers in the management of delirium in general acute care settings: An integrative review. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 2023a;42(4):638-48.

Lee‐Steere K, Liddle J, Mudge A, Bennett S, McRae P, Barrimore SE. “You’ve got to keep moving, keep going”: understanding older patients’ experiences and perceptions of delirium and nonpharmacological delirium prevention strategies in the acute hospital setting. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2020;29(13-14):2363-77.

Martins S, Conceição F, Paiva JA, Simões MR, Fernandes L. Delirium recognition by family: European Portuguese validation study of the family confusion assessment method. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2014;62(9):1748-52.

McKenzie J, Joy A. Family intervention improves outcomes for patients with delirium: Systematic review and meta‐analysis. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 2020;39(1):21-30.

Rosenbloom-Brunton DA, Henneman EA, Inouye SK. Feasibility of family participation in a delirium prevention program for hospitalized older adults. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2010;36(9):22-35.

Rosenbloom DA, Fick DM. Nurse/family caregiver intervention for delirium increases delirium knowledge and improves attitudes toward partnership. Geriatric Nursing. 2014;35(3):175-81.

Shrestha P, Fick DM. Family caregiver's experience of caring for an older adult with delirium: a systematic review. International Journal of Older People Nursing. 2020;15(4):e12321.

Bull MJ, Boaz L, Jermé M. Educating Family Caregivers for Older Adults About Delirium: A Systematic Review. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing. 2016;13(3):232-40.

Boltz M, Resnick B, Chippendale T, Galvin J. Testing a family‐centered intervention to promote functional and cognitive recovery in hospitalized older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2014;62(12):2398-407.

Cohen C, Pereira F, Kampel T, Bélanger L. Integration of family caregivers in delirium prevention care for hospitalized older adults: A case study analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2021;77(1):318-30.

Cervero RM, Gaines JK. The Impact of CME on Physician Performance and Patient Health Outcomes: An Updated Synthesis of Systematic Reviews. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2015;35(2):131-8.

Lee SY, Fisher J, Wand APF, Milisen K, Detroyer E, Sockalingam S, et al. Developing delirium best practice: a systematic review of education interventions for healthcare professionals working in inpatient settings. European Geriatric Medicine. 2020;11(1):1-32.

Aggar C, Craswell A, Bail K, Compton R, Hughes M, Sorwar G, et al. A co-designed web-based Delirium Toolkit for carers: An eDelphi evaluation of usability and quality. Collegian. 2023b;30(2):380-5.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Canberra. Australian Institute of Health & Welfare; 2023.

Qualtrics. Qualtrics software. USA. 2023. Accessed October, 2023. https://www.qualtrics.com

Racine AM, D'Aquila M, Schmitt EM, Gallagher J, Marcantonio ER, Jones RN, et al. Delirium Burden in Patients and Family Caregivers: Development and Testing of New Instruments. The Gerontologist. 2019;59(5):e393-e402.

Bull MJ, Avery JS, Boaz L, Oswald D. Psychometric Properties of the Family Caregiver Delirium Knowledge Questionnaire. Research in Gerontological Nursing. 2015;8(4):198-207.

Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand S-L, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32(6):959-76.

Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184-9.

IBM Corp. SSPSS Statistics for Windows. V27.0 [Computer software]. IBM Corp. 2020.

Dean AG, Sullivan KM, Soe MM. OpenEpi: Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health. 2013. V3.01. Accessed October, 2023. https://www.openepi.com/PersonTime2/PersonTime2.htm.

Mishra P, Pandey CM, Singh U, Gupta A, Sahu C, Keshri A. Descriptive statistics and normality tests for statistical data. Annals of Cardiac Anaesthesia. 2019;22(1):67-72.

Tomczak M, Tomczak E. The need to report effect size estimates revisited. An overview of some recommended measures of effect size. 2014;21:19-25.

Alexander L, Lopes B, Richetti-Masterson K, Yeatts K. Eric Notebook: Risk and Rate Measures in Cohort Studies. 2015. 2 ed. Accessed October, 2023. nciph_ERIC7.pdf (unc.edu)

Rothman KJ. Epidemiology: an introduction: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Hagger MS, Luszczynska A, De Wit J, Benyamini Y, Burkert S, Chamberland P-E, et al. Implementation intention and planning interventions in Health Psychology: Recommendations from the Synergy Expert Group for research and practice. Psychology and Health. 2016;31(7):814-39.

Andrews G, Slade T. Interpreting scores on the Kessler psychological distress scale (K10). Australian and New Zealand journal of public health. 2001;25(6):494-7.

Meyer G, Mauch M, Seeger Y, Burckhardt M. Experiences of relatives of patients with delirium due to an acute health event - A systematic review of qualitative studies. Appl Nurs Res. 2023;73:151722.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Delirium: prevention, diagnosis and management in hospital and long-term care (clinical guideline CG103). U.K. NICE; 2023.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare. Delirium Clinical Care Standard. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2021.

Aldecoa C, Bettelli G, Bilotta F, Sanders RD, Audisio R, Borozdina A, et al. European Society of Anaesthesiology evidence-based and consensus-based guideline on postoperative delirium. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2017;34(4):192-214.

Martins S, Pinho E, Correia R, Moreira E, Lopes L, Paiva JA, et al. What effect does delirium have on family and nurses of older adult patients? Aging and Mental Health. 2018;22(7):903-11.

Schmitt EM, Gallagher J, Albuquerque A, Tabloski P, Lee HJ, Gleason L, et al. Perspectives on the Delirium Experience and Its Burden: Common Themes Among Older Patients, Their Family Caregivers, and Nurses. The Gerontologist. 2019;59(2):327-37.

Liu Z, Heffernan C, Tan J. Caregiver burden: A concept analysis. International Journal of Nursing Sciences. 2020;7(4):438-45.

Cherak SJ, Rosgen BK, Amarbayan M, Wollny K, Doig CJ, Patten SB, et al. Mental Health Interventions to Improve Psychological Outcomes in Informal Caregivers of Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Critical Care Medicine. 2021;49(9):1414-26.

Anderson JG, Flatt JD. Characteristics of LGBT caregivers of older adults: Results from the national Caregiving in the U.S. 2015 survey. Journal of gay & lesbian social services. 2018;30(2):103-16.

Reid N, Gamage T, Duckett SJ, Gray LC. Hospital utilisation in Australia, 1993-2020, with a focus on use by people over 75 years of age: a review of AIHW data. The Medical journal of Australia. 2023;219(3):113-119. doi:https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.52026

Acknowledgements

Nursing staff who supported the dissemination of Carer Delirium Toolkit and partnering with carers. Nurse leaders who advocated for the Carer Delirium Toolkit: Brenda Paddon, Princy Albert, and Hannah Graves. Tamsin Thomas and Tina Prassos for supporting the analysis of this study and preparation of the paper for publication and most importantly the study participants for sharing their experiences.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author Contribution

-

(i)

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work;

-

(ii)

Substantial contributions to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data;

-

(iii)

Drafting the work;

-

(iv)

Revising the work critically for important intellectual content;

-

(v)

Final approval of the version to be published;

-

(vi)

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Christina Aggar | i–vi |

Alison Craswell | i–vi |

Kasia Bail | i–vi |

Roslyn Compton | i–vi |

Mark Hughes | i, iii–vi |

Golam Sorwar | i, iii–vi |

James Baker | i, iii–vi |

Lucy Shinners | i, iii–vi |

Jenenne Greenhill | i, iv–vi |

Belinda Nichols | i, iv–vi |

Karen Bowen | i, iv–vi |

Allsion Wallis | i, iv–vi |

Hazel Bridgett | i, iv–vi |

Rachel Langheim | i, iv–vi |

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Approval was provided by the North Coast of NSW Human Research Ethics Committee NCNSW HREC (HREA327 2021/ETH11752).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aggar, C., Craswell, A., Bail, K. et al. A Toolkit for Delirium Identification and Promoting Partnerships Between Carers and Nurses: A Pilot Pre–Post Feasibility Study. J GEN INTERN MED (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-08734-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-08734-6