Abstract

Objectives

In a 5-year multifactorial risk reduction intervention for healthy men with at least one cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factor, mortality was unexpectedly higher in the intervention than the control group during the first 15-year follow-up. In order to find explanations for the adverse outcome, we have extended mortality follow-up and examined in greater detail baseline characteristics that contributed to total mortality.

Design

Long-term follow-up of a controlled intervention trial.

Setting

The Helsinki Businessmen Study Intervention Trial.

Participants and Intervention

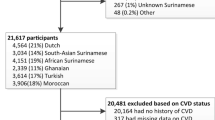

The prevention trial between 1974–1980 included 1,222 initially healthy men (born 1919–1934) at high CVD risk, who were randomly allocated into intervention (n=612) and control groups (n=610). The 5-year multifactorial intervention consisted of personal health education and contemporary drug treatments for dyslipidemia and hypertension. In the present analysis we used previously unpublished data on baseline risk factors and lifestyle characteristics.

Main outcome measures

40-year total and cause-specific mortality through linkage to nation-wide death registers.

Results

The study groups were practically identical at baseline in 1974, and the 5-year intervention significantly improved risk factors (body mass index, blood pressure, serum lipids and glucose), and total CVD risk by 46% in the intervention group. Despite this, total mortality has been consistently higher up to 25 years post-trial in the intervention group than the control group, and converging thereafter. Increased mortality risk was driven by CVD and accidental deaths. Of the newly-analysed baseline factors, there was a significant interaction for mortality between intervention group and yearly vacation time (P=0.027): shorter vacation was associated with excess 30-year mortality in the intervention (hazard ratio 1.37, 95% CI 1.03–1.83, P=0.03), but not in the control group (P=0.5). This finding was robust to multivariable adjustments.

Conclusion

After a multifactorial intervention for healthy men with at least one CVD risk factor, there has been an unexpectedly increased mortality in the intervention group. This increase was especially observed in a subgroup characterised by shorter vacation time at baseline. Although this adverse response to personal preventive measures in vulnerable individuals may be characteristic to men of high social status with subclinical CVD, it clearly deserves further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Miettinen TA, Huttunen JK, Naukkarinen V, et al. Multifactorial primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases in middle-aged men. JAMA 1985;254:2097–2102.

Strandberg TE, Salomaa VV, Naukkarinen VA, Vanhanen HT, Sarna SJ, Miettinen TA. Long-term mortality after 5–year multifactorial primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases in middle-aged men. JAMA 1991;266:1225–1229.

Strandberg TE, Salomaa VV, Vanhanen HT, Naukkarinen V, Sarna S, Miettinen TA. Mortality in participants and non-participants of a multifactorial prevention study of cardiovascular diseases: a 28 year follow up of the Helsinki Businessmen Study. Br Heart J 1995;74:449–454.

Strandberg TE, Salomaa V, Strandberg AY, et al. Cohort Profile: The Helsinki Businessmen Study (HBS). Int J Epidemiol 2016;45:1074–1074h.

Paul O, Hennekens CH. The latest report from Finland. A lesson in expectations. JAMA 1991;266:1267–1268.

Oliver MF. Doubts about preventing coronary heart disease. BMJ 1992;304:393–394.

Anonymous. Should clinical trials carry a health warning? (Editorial) Lancet 1991;338:1495–6.

Stamler J. Lessons from the Helsinki Multifactorial Primary Prevention Trial. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 1995;5:1–5.

Gump BB, Matthews KA. Are vacations good for your health? The 9-year mortality experience after the multiple risk factor intervention trial. Psychosom Med 2000;62:608–12.

Kivimäki M, Jokela M, Nyberg ST, et al, IPD-Work Consortium. Long working hours and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished data for 603,838 individuals. Lancet 2015;386(10005): 1739–46

Kripke DF, Garfinkel L, Wingard DL, Klauber M, Marler M. Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59:131–36.

Keys A, Aravanis C, Blackburn H, et al. Probability of middle-aged men developing coronary heart disease in five years. Circulation 197245:815–828.

Marmot MG, Shipley MJ. Do Socioeconomic differences in mortality persist after retirement? 25 year follow up of civil servants from the first Whitehall study. BMJ 1996;313:1177–1180.

Carnethon M, Whitsel LP, Franklin BA, et al. American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease; Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism. Worksite wellness programs for cardiovascular disease prevention: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2009;120:1725–41. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192653.

Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al; Authors/Task Force Members. European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J 2016;37:2315–81.

Rosengeren A, Hawken S, Öunpuu S, et al For the INTERHEART investigators. Association of psychosocial risk factors with risk of acute myocardial infarction in 11119 cases and 13648 controls from 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): casecontrol study. Lancet 2004;364:953–62.

Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Davidson KW, Saab PG, Kubzanski L. The epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management of psychosocial risk factors in cardiac practice. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:637–51

Kivimäki M, Nyberg ST, Batty GD, et al; IPD-Work Consortium. Job strain as a risk factor for coronary heart disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet 2012;380:1491–7.

Arnold SV, Smolderen KG, Buchanan DM, Li Y, Spertus JA. Perceived stress in myocardial infarction: long-term mortality and health status outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1756–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.06.044.

Evans DL, Charney DS, Lewis L, et al. Mood disorders in the medically ill. Biol Psychiatry 2005;58:175–89.

Smyth A, O’Donnell M, Lamelas P, Teo K, Rangarajan S, Yusuf S. INTERHEART Investigators. Physical Activity and Anger or Emotional Upset as Triggers of Acute Myocardial Infarction: The INTERHEART Study. Circulation 2016;134:1059–1067.

Järvinen KAJ. Can ward rounds be a danger to patients with myocardial infarction. Br Med J 1955;1;318–320.

Jeong YJ, Aldwin CM, Igarashi H, Spiro A 3rd. Do hassles and uplifts trajectories predict mortality? Longitudinal findings from the VA Normative Aging Study. J Behav Med 2016;39:408–19.

Björntorp P. Hypothesis. Visceral fat accumulation: the missing link between psychosocial factors and cardiovascular disease? J Intern Med 1991;230:195–201.

Muldoon MF, Herbert TB, Patterson SM, Kameneva M, Raible R, Manuck SB. Effects of acute psychological stress on serum lipid levels, hemoconcentration, and blood viscosity. Arch Intern Med 1995;155:615–620.

Yeung AC, Vekhstein VI, Krantz DS, et al. The effect of atherosclerosis on the vasomotor response of coronary arteries to mental stress. N Engl J Med 1991;325:1551–6.

Kawachi I, Sparrow D, Vokonas PS, Weiss ST. Decreased heart rate variability in men with phobic anxiety (Data from the Normative Aging Study). Am J Cardiol 1995;75:882–885.

McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N Engl J Med 1998;338:171–178.

Karatsoreos IN, McEwen BS. Psychological allostasis: resistance, resilience and vulnerability. Trends Cognit Dis 2011;15:576–584.

McEwen BS, Bowles NP, Gray JD, et al (2015) Mechanisms of stress in the brain. Nat Neurosci 201518:1353–1363.

Steptoe A, Kivimäki M. Stress and cardiovascular disease. Nature Reviews Cardiol 2012;9:360–370.

Raitakari OT, Juonala M, Kahonen M, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in childhood and carotid artery intima-media thickness in adulthood: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. JAMA 2003;290:2277–2283.

Rosengren A, Orth-Gomer K, Wedel H, Wilhelmsen L. Stressful life events, social support, and mortality in men born in 1933. Br Med J 1993;307:1102–1105.

Carroll D, Ginty AT, Der G, Hunt K, Benzeval M, Phillips AC. Increased blood pressure reactions to acute mental stress are associated with 16–year cardiovascular disease mortality. Psychophysiology 2012;49:1444–8.

Uthman OA, Hartley L, Rees K, Taylor F, Ebrahim S, Clarke A. Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in low- and middleincome countries. Cochrane Review 2015; DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011163. pub2

Ebrahim S, Taylor F, Ward K, Beswick A, Burke M, Davey Smith G. Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of coronary heart disease. Cochrane Review 2011;DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001561.pub3

Hjermann I, Velve Byre K, Holme I, Leren P. Effect of diet and smoking intervention on the incidence of coronary heart disease. Report from the Oslo study group of a randomised trial in healthy men. Lancet 1981;ii:1303–1310.

Ornish D, Brown SE, Scherwitz LW, et al. Can lifestyle changes reverse coronary heart disease? The Lifestyle Heart Trial. Lancet 1990;336:129–133.

Haskell WL, Alderman EL, Fair JM, et al. Effects of intensive multiple risk factor reduction on coronary atherosclerosis and clinical cardiac events in men and women with coronary artery disease. The Stanford Coronary Risk Intervention Project (SCRIP). Circulation 1994;89:975–990.

The Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research Group. Mortality after 16 years for participants randomized to the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Circulation 1996;94:946–951.

Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson JG, et al. Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1343–50.

Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002346:393–403.

The Look AHEAD Research Group. Cardiovascular effects of intesive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2013;369:145–54.

Shively CA, Day SM. Social inequalities in health in nonhuman primates. Neurobiol Stress 2014;1:156–63.

Strandberg TE, von Bonsdorff M, Strandberg A, Pitkälä K, Räikkönen K. Associations of vacation time with lifestyle, long-term mortality and healthrelated quality of life in old age: The Helsinki Businessmen Study. Eur Geriatr Med 2017;8:260–264.

Charlew ST, Piazza JR, Mogle J, Sliwinski MJ, Almeida DM. The wear-and-tear of daily stressors on mental health. Psychol Sci 2013;24:733–741.

Bot I, Kuiper J. Stressed brain, stressed heart? Lancet 2017;389:770–771.

Welch HG. Questions about the value of early intervention. N Engl J Med 1996;334:1472–1473.

Sweeney KG, Pereira Gray DJ, Evans PH. Steele RJF. The doctrine of early intervention. BMJ 1996;313:1097.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Strandberg, T.E., Räikkönen, K., Salomaa, V. et al. Increased Mortality Despite Successful Multifactorial Cardiovascular Risk Reduction in Healthy Men: 40-Year Follow-Up of the Helsinki Businessmen Study Intervention Trial. J Nutr Health Aging 22, 885–891 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-018-1099-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-018-1099-0