Abstract

The propagation of surface-plasmon-polariton (SPP) waves guided by the planar interface of (1) an isotropic metal and (2) an active uniaxial dielectric material was theoretically investigated, under the assumption that the optic axis of the uniaxial partnering material lies wholly in the interface plane. The uniaxial partnering material was conceptualized as a homogenized composite material (HCM) arising from both non-dissipative and active component materials. For a certain range of the volume fraction of the active component material, the SPP waves propagating in certain directions in the interface plane are amplified, but the SPP waves propagating in other directions are attenuated. In a critical propagation direction, the SPP wave is neither amplified nor attenuated. This critical propagation direction was found to be acutely sensitive to the composition of the HCM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent times, engineered materials with exotic optical properties, as typified by metamaterials [1], have provided the backdrop for substantial developments in nanotechnology, at least at the conceptualization stage, and sometimes beyond [2]. In particular, when active and dissipative component materials are judiciously combined to form composite materials, the role of the active component material can surpass the simple act of overcoming the debilitating effects of dissipation [3,4,5,6]. Homogenization theory predicts that a random mixture of aligned spheroidal particles, made from both active and dissipative materials, can function optically as a homogeneous uniaxial dielectric continuum in which plane waves propagating in certain propagation directions are amplified, but plane waves propagating in other propagation directions are attenuated [7]. In a similar vein, a stack of alternate active and dissipative layers can function as a homogeneous birefringent continuum capable of controlling plane-wave polarization states [8]. Certain mixtures of active and dissipative component materials are, in effect, homogenized composite materials (HCMs) which (a) amplify circularly polarized light of one handedness but attenuate circularly polarized light of the other handedness [9], and other mixtures are HCMs that (b) amplify incident light of one linear polarization state but attenuate incident light of the orthogonal polarization state [10].

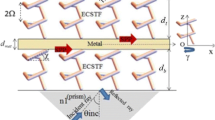

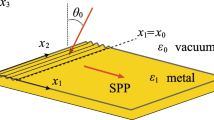

In this paper, the focus is on surface-plasmon-polariton (SPP) waves. The SPP wave is probably the most technologically important of the many different types of electromagnetic surface wave [11]; they are widely exploited in optical sensing applications [12, 13], for example. Indeed, the prospect of achieving lossless SPP-wave propagation in preferred directions, which may be particularly useful for long-range optical communications, motivated the present study. Here, we consider SPP waves guided by the planar interface of an active anisotropic dielectric HCM and an isotropic metal (i.e., a dissipative dielectric material whose relative permittivity has a negative-valued real part). The chosen HCM arises from the homogenization of two component materials: a non-dissipative dielectric material and an active dielectric material. The prospects for amplification and attenuation of SPP waves are explored numerically, by solving the corresponding canonical boundary-value problem [11] wherein the half-space \(z<0\) is filled with the dissipative metal, whereas the half-space \(z>0\) is filled with the active HCM. As regards notation, \( \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,x}\), \(\hat{\underline{u}}_{\,y}\), and \(\hat{\underline{u}}_{\,z}\) denote the three unit vectors parallel to the Cartesian axes; \(k_{0}= \omega \sqrt{\epsilon _{0}\mu _{0}}\) denotes the free-space wave number with \(\omega \) as the angular frequency and \(\epsilon _{0}\) and \(\mu _{0}\) as the permittivity and permeability of free space, respectively.

The theoretical framework for SPP-wave propagation guided by the planar interface of a metal and a uniaxial dielectric material whose optic axis is oriented to lie wholly in the interface plane is available in detail elsewhere [11, 14,15,16]. Accordingly, only the bare essentials are presented here. The uniaxial partnering material occupying the half-space \(z>0\) is assigned the label \({\mathcal {A}}\). The relative permittivity dyadic of material \({\mathcal {A}}\) is written as

Herein \(\underline{\underline{I}} = \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,x}\,\hat{\underline{u}}_{\,x}+ \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,y}\, \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,y}+ \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,z}\, \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,z}\) is the identity 3 \( \times \) 3 dyadic [17] and the optic axis of material \({\mathcal {A}}\) is parallel to the unit vector

which lies in the xy plane at an angle \(\psi \) with respect to \(\hat{\underline{u}}_{\,x}\). Since material \({\mathcal {A}}\) is uniaxial, both (1) ordinary plane waves governed by \(\epsilon _{\mathcal {A}}^\mathrm{s}\) and (2) extraordinary plane waves governed jointly by \(\epsilon _{\mathcal {A}}^\mathrm{t}\) and \(\epsilon _{\mathcal {A}}^\mathrm{s}\) can propagate in it [18]. The metal occupying the half-space \(z<0\) is assigned the label \({\mathcal {B}}\). Its relative permittivity is written as \(\epsilon _{\mathcal {B}}=n^2_{\mathcal {B}}\). A schematic illustration of the regions occupied by materials \({\mathcal {A}}\) and \({\mathcal {B}}\) is provided in Fig. 1.

Let an SPP wave propagate parallel to \(\hat{\underline{u}}_{\,x}\) in the xy plane, with q being the surface wavenumber. There is no loss of generality accrued by this assumption, since the angle \(\psi \) of the optic axis is not fixed. Because of fourfold symmetry in the xy plane, we only consider \(\psi \in [0,\pi /2]\).

In order to determine the normalized wavenumber \({\tilde{q}}=q/k_{0}\), \(\mathrm{Re}\left\{ {\tilde{q}}\right\} >0\), the dispersion equation [11]

is solved numerically. Herein the decay constants

are such that \(\mathrm{Re}\left\{ \alpha _{{\mathcal {A}}1}\right\} >0\), \(\mathrm{Re}\left\{ \alpha _{{\mathcal {A}}2}\right\} >0\), and \(\mathrm{Re}\left\{ \alpha _{\mathcal {B}}\right\} >0\).

Thus, the SPP wave is amplified as it propagates if \(\mathrm{Im}\left\{ {\tilde{q}}\right\} < 0\), whereas it is attenuated if \(\mathrm{Im}\left\{ {\tilde{q}}\right\} > 0\). If \(\mathrm{Im}\left\{ {\tilde{q}}\right\} = 0\) then the SPP wave propagates without amplification or attenuation.

Numerical studies

Partnering materials

The combined effects of dissipation and amplification in the nonmetallic partnering material on SPP-wave propagation are conveniently explored by taking material \({\mathcal {A}}\) to be an HCM, arising from two component materials: component material \({\mathcal {A}}a\) and component material \({\mathcal {A}}b\). Both component materials \({\mathcal {A}}a\) and \({\mathcal {A}}b\) are isotropic dielectric materials, with relative permittivities written as \(\epsilon _{{\mathcal {A}}a}\) and \(\epsilon _{{\mathcal {A}}b}\), respectively. The volume fractions of these materials are written as \(f_{{\mathcal {A}}a}\) and \(f_{{\mathcal {A}}b}=1-f_{{\mathcal {A}}a}\). The anisotropy of the HCM stems from the shapes of the particles making up component materials \({\mathcal {A}}a\) and \({\mathcal {A}}b\). We assume that the component materials are randomly distributed as aciculate particles oriented parallel to \(\hat{\underline{u}}\) [19]. Thus, the following estimates for the relative permittivity parameters of material \({\mathcal {A}}\) are yielded by the Bruggeman homogenization formalism [20]:

Parenthetically, a similarly anisotropic continuum could arise from the homogenization of a periodic multilayer [18].

A non-dissipative dielectric material was chosen for component material \({\mathcal {A}}a\). Specifically, \(\epsilon _{{\mathcal {A}}a} = 4.426\), which is the relative permittivity of hafnium dioxide–yttrium oxide at a free-space wavelength of 650 nm [21]. An active dielectric material was chosen for component material \({\mathcal {A}}b\). Specifically, \(\epsilon _{{\mathcal {A}}b} = 2 - 0.1 i \), which lies comfortably within the range of relative permittivities typically encountered for active components of metamaterials at wavelengths in the visible regime. For example, across the frequency range 440–500 THz, a mixture of Rhodamine 800 and Rhodamine 6G has a relative permittivity with imaginary part in the range \(\left( -0.15, -0.02 \right) \) and real part in the range \(\left( 1.8, 2.3 \right) \), depending upon the relative concentrations and the external pumping rate [6].

In Fig. 2, plots are presented of the Bruggeman estimates of \(\epsilon _{\mathcal {A}}^\mathrm{s}\) and \(\epsilon _{\mathcal {A}}^\mathrm{t}\) versus volume fraction \(f_{{\mathcal {A}}b}\). Clearly, both \(\text{ Im } \left\{ \epsilon _{\mathcal {A}}^\mathrm{s} \right\} < 0\) and \(\text{ Im } \left\{ \epsilon _{\mathcal {A}}^\mathrm{t} \right\} <0\) for \(0< f_{{\mathcal {A}}b} < 1\). Therefore, the HCM is wholly active, regardless of volume fractions of the two component materials. Also, the degree of anisotropy of the HCM, as represented by both the real and imaginary parts of \(\epsilon _{\mathcal {A}}^\mathrm{s}\) and \(\epsilon _{\mathcal {A}}^\mathrm{t}\), is greatest for mid-range values of \(f_{{\mathcal {A}}b}\). Only in the limits \( f_{{\mathcal {A}}b} \rightarrow 0\) and \(f_{{\mathcal {A}}b} \rightarrow 1\) does the HCM become isotropic.

Surface-wave analysis

Now we turn to SPP waves guided by the planar interface at \(z=0\). For this purpose, the metal occupying the half-space \(z<0\) was selected to be silver. Thus, \(\epsilon _{\mathcal {B}} = -19.440 + 0.461 i\) which represents the relative permittivity of silver at a free-space wavelength of 650 nm [22]. In Fig. 3, the real and imaginary parts of the normalized wavenumber \({\tilde{q}}\), as calculated from Eq. (3) using Eq. (4), are plotted versus the propagation angle \(\psi \) for \(f_{{\mathcal {A}}b} \in \left\{ 0.110, 0.116, 0.122 \right\} \). Unlike the case for Dyakonov surface waves [23, 24], for example, SPP-wave propagation is possible for all values of \(\psi \). When \(f_{{\mathcal {A}}b} = 0.110\), the imaginary part of \({\tilde{q}}\) is positive, regardless of the value of \(\psi \). (The same is true when \(0< f_{{\mathcal {A}}b} < 0.110\), but these results are not presented here). When \(f_{{\mathcal {A}}b} = 0.122\), the imaginary part of \({\tilde{q}}\) is negative, regardless of the value of \(\psi \). (The same is true when \(0.122< f_{{\mathcal {A}}b} < 1\), but these results are not presented here). Therefore, SPP waves are attenuated for small values of \(f_{{\mathcal {A}}b}\) but amplified at large values of \(f_{{\mathcal {A}}b}\), regardless of the direction of propagation.

Most interestingly, when \(f_{{\mathcal {A}}b}\) lies between 0.110 and 0.122, the imaginary part of \({\tilde{q}}\) is positive for small values of \(\psi \in [0,\pi /2]\) but negative for large values of \(\psi \in [0,\pi /2]\). For example, in the case of \(f_{{\mathcal {A}}b} = 0.116\) represented in Fig. 3, \(\text{ Im } \left\{ {\tilde{q}}\right\} > 0\) for \(\psi < 42.7^\circ \), whereas \(\text{ Im } \left\{ {\tilde{q}}\right\} < 0\) for \(\psi > 42.7^\circ \) . Thus, at intermediate values of \(f_{{\mathcal {A}}b}\), SPP waves are attenuated for certain propagation directions but amplified for other propagation directions.

Further light is shed on this matter by considering the electric field phasor \(\underline{E} (\underline{r}) = \underline{{\mathcal {E}}} \exp \left( i \underline{k} {\,{^\bullet }\, }\underline{r} \right) \), with complex-valued amplitude vector \(\underline{{\mathcal {E}}}\) and wave vector \(\underline{k}\), in the xz plane for the regions above and below the interface \(z=0\). The magnitudes of the Cartesian components of \(\underline{E} (x \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,x}+ z \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,z})\) are mapped in the xz plane in Fig. 4 for the case where \(\psi = 25.0^\circ \) and \(f_{{\mathcal {A}}b} = 0.116\); then \({\tilde{q}} = 2.26616 + 0.00020 i\) according to Fig. 3 and the SPP wave attenuates in the \(+ \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,x}\) direction. From Fig. 4, the attenuation is much less strong in the \(+\hat{\underline{u}}_{\,x}\) direction than it is in the \(\pm \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,z}\) directions, with attenuation in the \(-\hat{\underline{u}}_{\,z}\) direction being much stronger than in the \(+\hat{\underline{u}}_{\,z}\) direction. Furthermore, it is clear from Fig. 4 that the maximum of \( | \underline{E} (x \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,x}+ z \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,z}) | \) is not concentrated at the interface \(z=0\) but instead in the region slightly above the interface. This is particularly conspicuous in the case of the y-directed component of \(\underline{E} (x \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,x}+ z \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,z})\).

The field maps for \(\psi = 42.7^\circ \) are provided in Fig. 5. At this value of \(\psi \) we see from Fig. 3 that \({\tilde{q}}\) is purely real valued, i.e., \({\tilde{q}} = 2.26453\). Consequently, in Fig. 5 there is no attenuation or amplification observable in the \(\hat{\underline{u}}_{\,x}\) direction.

The case where the SPP wave is amplified is represented in Fig. 6 wherein the field maps for \(\psi = 65.0^\circ \) are provided. For this value of \(\psi \), we see from Fig. 3 that \({\tilde{q}} = 2.26246 - 0.00026 i \). The pattern of amplification of \( | \underline{E} (x \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,x}+ z \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,z}) | \) apparent in Fig. 6 is the opposite of the pattern of attenuation apparent in Fig. 4, with the maximum of \( | \underline{E} (x \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,x}+ z \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,z}) | \) in Fig. 6 being concentrated in the region slightly above the interface \(z=0\), especially so in the case of the y-directed component of \(\underline{E} (x \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,x}+ z \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,z})\).

Magnitude of \(\underline{E} (x \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,x}+ z \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,z}){\,{^\bullet }\, }\underline{n}\) for \(\underline{n} \in \left\{ \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,x}, \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,y}, \hat{\underline{u}}_{\,z}\right\} \) plotted versus \(x/\lambda _{0}\) and \(z/\lambda _{0}\) when \(\psi = 25.0^\circ \) and \(f_{{\mathcal {A}}b} = 0.116\). Normalization: \(\underline{{\mathcal {E}}} {\,{^\bullet }\, }\hat{\underline{u}}_{\,y}=1\hbox { V m}^{-1}\) for \(z < 0\)

As Fig. 4 but with \(\psi = 42.7^\circ \)

As Fig. 4 but with \(\psi = 65.0^\circ \)

The transition from \(\text{ Im } \left\{ {\tilde{q}}\right\} > 0\) to \(\text{ Im } \left\{ {\tilde{q}}\right\} < 0\) as \(\psi \) increases, as illustrated in Fig. 3 for \(f_{{\mathcal {A}}b} = 0.116\), is smooth. Consequently, there exists a critical value \(\psi _c\) of \(\psi \) which \(\text{ Im } \left\{ {\tilde{q}}\right\} = 0\). For example, \(\psi _c = 42.7^\circ \) for at \(f_{{\mathcal {A}}b} = 0.116\). At this critical propagation angle, the SPP wave propagates without amplification or attenuation. This matter is pursued in Fig. 7 wherein the critical angle \(\psi _c\) is plotted versus \(f_{{\mathcal {A}}b}\). Clearly, \(\psi _c\) is highly sensitive to changes in \(f_{{\mathcal {A}}b}\). For example, as \(f_{{\mathcal {A}}b}\) increases from 0.112 to 0.120, \(\psi _c\) decreases in an approximately linear manner from \(67.5^\circ \) to \(16.5^\circ \).

In order to explore further the sensitivity of \(\psi _c\) to changes in the composition of the material occupying the half-space \(z>0\), we fixed \(f_{{\mathcal {A}}b} = 0.116\) but allow the constitutive properties of component material \({\mathcal {A}}a\) to vary. To more conveniently allow comparisons with optical sensing studies, let us introduce the refractive index of component material \({\mathcal {A}}a\), namely \(n_{{\mathcal {A}}a} = \sqrt{\epsilon _{{\mathcal {A}}a}}\). In Fig. 8, the critical propagation direction \(\psi _c\) is plotted against \(n_{{\mathcal {A}}a}\), with \(n_{{\mathcal {A}}a}\) centered on \(\sqrt{4.426} = 2.104\). Clearly, \(\psi _c\) is highly sensitive to changes in \(n_{{\mathcal {A}}a}\). For example, as \(n_{{\mathcal {A}}a}\) increases from 2.08 to 2.15, \(\psi _c\) increases in an approximately linear manner from \(24.5^\circ \) to \(79.5^\circ \), which corresponds to an approximate sensitivity of 786 degrees per refractive index unit.

Closing remarks

To conclude, SPP waves guided by the planar interface of an isotropic metal and a uniaxial dielectric HCM, arising from both non-dissipative and active component materials, were theoretically investigated for the case where the optic axis of the uniaxial HCM lies wholly in the interface plane. At low values of the volume fraction of the active component material, the SPP wave is attenuated, while amplification occurs at high values of the same volume fraction, regardless of the propagation direction. However, for a relatively small range of intermediate volume-fraction values, the SPP waves propagating in certain directions in the interface plane are amplified, but the SPP waves propagating in other directions are attenuated. Furthermore, in a critical propagation direction the SPP wave is neither amplified nor attenuated. The critical propagation direction is acutely sensitive to the composition of the HCM. These characteristics may be harnessed for applications involving optical sensing and/or optical communications.

Lossless solutions, arising from a combination of an isotropic dissipative material and an isotropic active material, appear in the context of PT-symmetric materials [25]. Thus, if \(\underline{\underline{\epsilon }}_{\mathcal {\,A}} = n^2_{\mathcal {A}} \underline{\underline{I}}\), then lossless surface waves may arise provided that \( n_{\mathcal {A}}\) and \( n_{\mathcal {B}}\) are complex conjugates. As an example, if \( n_{\mathcal {A}}=4-0.2i\) and \( n_{\mathcal {B}}=4+0.2i\), then \(\alpha _{{\mathcal {A}}1}=\alpha _{{\mathcal {A}}2}= 0.283+2.825i\), \(\alpha _{{\mathcal {B}}}=0.283-2.825i\), and \({\tilde{q}}=2.839\). However, no such symmetry relating the constitutive parameters of materials \({\mathcal {A}}\) and \({\mathcal {B}}\) is apparent when material \({\mathcal {A}}\) is a uniaxial dielectric material, the complexity of the dispersion Eq. (3) obscuring any such symmetry.

Lastly, let us note that this directional attenuation/amplification phenomenon stems from the anisotropy of the HCM: if the HCM were to be isotropic instead of anisotropic then the characteristics of the SPP wave would be the same for all propagation directions.

References

R.M. Walser, Electromagnetic metamaterials. Proc. SPIE 4467, 1 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1117/12.432921

R. Vajtai (ed.), Springer Handbook of Nanomaterials (Springer, New York, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-20595-8

S. Wuestner, A. Pusch, K.L. Tsakmakidis, J.M. Hamm, O. Hess, Overcoming losses with gain in a negative refractive index metamaterial. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 127401 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.127401

Z.-G. Dong, H. Liu, T. Li, Z.-H. Zhu, S.-M. Wang, J.-X. Cao, S.-N. Zhu, X. Zhang, Optical loss compensation in a bulk left-handed metamaterial by the gain in quantum dots. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 044104 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3302409

G. Strangi, A. De Luca, S. Ravaine, M. Ferrie, R. Bartolino, Gain induced optical transparency in metamaterials. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 251912 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3599566

L. Sun, X. Yang, J. Gao, Loss-compensated broadband epsilon-near-zero metamaterials with gain media. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 201109 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4831768

T.G. Mackay, A. Lakhtakia, Dynamically controllable anisotropic metamaterials with simultaneous attenuation and amplification. Phys. Rev. A 92, 053847 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.92.053847

A. Cerjan, S. Fan, Achieving arbitrary control over pairs of polarization states using complex birefringent metamaterials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 253902 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.253902

T.G. Mackay, A. Lakhtakia, Simultaneous amplification and attenuation in isotropic chiral materials. J. Opt. (UK) 18, 055104 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1088/2040-8978/18/5/055104

T.G. Mackay, A. Lakhtakia, Polarization-state-dependent attenuation and amplification in a columnar thin film, J. Opt. (UK) 19, 12LT01 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1088/2040-8986/aa9127, erratum 20, 019501 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1088/2040-8986/aa9ec3

J.A. Polo Jr., T.G. Mackay, A. Lakhtakia, Electromagnetic Surface Waves: A Modern Perspective (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2013)

J. Homola (ed.), Surface Plasmon Resonance Based Sensors (Springer, Heidelberg, 2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/b100321

I. Abdulhalim, M. Zourob, A. Lakhtakia, Surface plasmon resonance for biosensing: a mini-review. Electromagnetics 28, 214–242 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1080/02726340801921650

G. Borstel, H.J. Falge, Surface phonon–polaritons, in Electromagnetic Surface Modes, Chapter 6, ed. by A.D. Boardman (Wiley, New York, 1982)

R.F. Wallis, Surface magnetoplasmons on semiconductors, in Electromagnetic Surface Modes, Chapter 15, ed. by A.D. Boardman (Wiley, New York, 1982)

I. Abdulhalim, Surface plasmon TE and TM waves at the anisotropic film-metal interface. J. Opt. A Pure Appl. Opt. 11, 015002 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1088/1464-4258/11/1/015002

H.C. Chen, Theory of Electromagnetic Waves: A Coordinate-Free Approach, Chapter 1 (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1983)

M. Born, E. Wolf, Principles of Optics 7th Expanded Edition, Chapter 15 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999)

W.S. Weiglhofer, A. Lakhtakia, J.C. Monzon, Maxwell–Garnett model for composites of electrically small uniaxial objects. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 6, 681–684 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1002/mop.4650061205

T.G. Mackay, Towards metamaterials with giant dielectric anisotropy via homogenization: an analytical study. Photon. Nanostruct. Fundam. Appl. 13, 8–19 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.photonics.2014.10.005

D.L. Wood, K. Nassau, T.Y. Kometani, D.L. Nash, Optical properties of cubic hafnia stabilized with yttria. Appl. Opt. 29, 604–607 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.29.000604

P.B. Johnson, R.W. Christy, Optical constants of the noble metals. Phys. Rev. B 6, 4370–4379 (1972). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.6.4370

M.I. D’yakonov, New type of electromagnetic wave propagating at an interface. Sov. Phys. JETP 67, 714–716 (1988)

O. Takayama, L. Crasovan, D. Artigas, L. Torner, Observation of Dyakonov surface waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 043903 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.043903

A.A. Zyablovsky, A.P. Vinogradov, A.A. Pukhov, A.V. Dorofeenko, A.A. Lisyansky, PT-symmetry in optics. Physics-Uspekhi 57, 1063–1082 (2014). https://doi.org/10.3367/UFNr.0184.201411b.1177

Acknowledgements

AL is grateful to the Charles Godfrey Binder Endowment at Penn State for ongoing support of his research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mackay, T.G., Lakhtakia, A. Simultaneous existence of amplified and attenuated surface-plasmon-polariton waves. J Opt 47, 527–533 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12596-018-0481-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12596-018-0481-y