Abstract

Objective

While evidence suggests that the mental health symptoms of COVID-19 can persist for several months following infection, little is known about the longer-term mental health effects and whether certain sociodemographic groups may be particularly impacted. This cross-sectional study aimed to characterize the longer-term mental health consequences of COVID-19 infection and examine whether such consequences are more pronounced in Black people and people with lower socioeconomic status.

Methods

277 Black and White adults (age ≥ 30 years) with a history of COVID-19 (tested positive ≥ 6 months prior to participation) or no history of COVID-19 infection completed a 45-minute online questionnaire battery.

Results

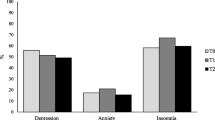

People with a history of COVID-19 had greater depressive (d = 0.24), anxiety (d = 0.34), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (d = 0.32), and insomnia (d = 0.31) symptoms than those without a history of COVID-19. These differences remained for anxiety, PTSD, and insomnia symptoms after adjusting for age, sex, race, education, income, employment status, body mass index, and smoking status. No differences were detected for perceived stress and general psychopathology. People with a history of COVID-19 had more than double the odds of clinically significant symptoms of anxiety (OR = 2.22) and PTSD (OR = 2.40). Education, but not race, income, or employment status, moderated relationships of interest such that COVID-19 status was more strongly and positively associated with all the mental health outcomes for those with fewer years of education.

Conclusion

The mental health consequences of COVID-19 may be significant, widespread, and persistent for at least 6 months post-infection and may increase as years of education decreases.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hopkins. Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Dashboard. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed March 1, 2022.

Datta SD, Talwar A, Lee JT. A proposed Framework and Timeline of the Spectrum of Disease due to SARS-CoV-2 infection: Illness beyond Acute Infection and Public Health Implications. JAMA. 2020;324(22):2251–2.

Groff D, et al. Short-term and long-term rates of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a systematic review. JAMA Netw open. 2021;4(10):e2128568–8.

Raveendran AV, Jayadevan R, Sashidharan S, Long COVID. An overview. Diabetes Metabolic Syndrome. 2021;15(3):869–75.

Greenhalgh T, et al. Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care. BMJ. 2020;370:m3026.

Michelen M, et al. Characterising long COVID: a living systematic review. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(9):e005427.

Taquet M et al. Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020.

Mazza MG, et al. Anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors: role of inflammatory and clinical predictors. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:594–600.

Méndez R et al. Short-term neuropsychiatric outcomes and quality of life in COVID-19 survivors. J Intern Med. 2021.

Huang C, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397(10270):220–32.

Paz C, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with confirmed and suspected COVID-19 in Ecuador. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;74(10):554–5.

Kappelmann N, Dantzer R, Khandaker GM. Interleukin-6 as potential mediator of long-term neuropsychiatric symptoms of COVID-19. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2021;131:105295.

Szcześniak D, et al. The SARS-CoV-2 and mental health: from biological mechanisms to social consequences. Prog Neuro-psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;104:110046–6.

Baldini T et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Neurol. 2021.

Lopez-Leon S et al. More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv. 2021.

Öngür D, Perlis R, Goff D. Psychiatry and COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(12):1149–50.

Assari S, Habibzadeh P. The COVID-19 emergency response should include a Mental Health Component. Arch Iran Med. 2020;23(4):281–2.

Noorullah A. Mounting toll of Coronavirus Cases Raises Concerns for Mental Health Professionals. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2020;30(7):677.

Davis HE et al. Characterizing long COVID in an International Cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. medRxiv. 2020; 2020.12.24.20248802.

Rodriguez F et al. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Presentation and Outcomes for Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19: Findings from the American Heart Association’s COVID-19 Cardiovascular Disease Registry. Circulation. 2020.

Hawkins RB, Charles EJ, Mehaffey JH. Socio-economic status and COVID-19-related cases and fatalities. Public Health. 2020;189:129–34.

Chen JT, Krieger N. Revealing the unequal burden of COVID-19 by income, Race/Ethnicity, and Household Crowding: US County Versus Zip Code analyses. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2021; S43–s56.

O’Rand AM. The precious and the precocious: understanding cumulative disadvantage and cumulative advantage over the life course. Gerontologist. 1996;36(2):230–8.

Adesogan O, et al. COVID-19 stress and the Health of Black americans in the Rural South. Clin Psychol Sci. 2021;10(6):1111–28.

Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995; p. 80–94.

Hall LR, et al. Income differences and COVID-19: impact on Daily Life and Mental Health. Popul Health Manage. 2021;25(3):384–91.

Assari S. Unequal gain of Equal resources across racial groups. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7(1):1–9.

Ayoubian A, Najand B, Assari S. Black americans’ diminished health returns of employment during COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Travel Med Global Health. 2022;10(3):114–21.

Berger E, et al. Multi-cohort study identifies social determinants of systemic inflammation over the life course. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):773–3.

Baumer Y, et al. Health disparities in COVID-19: addressing the Role of Social Determinants of Health in Immune System Dysfunction to turn the Tide. Front Public Health. 2020;8:559312–2.

Stepanikova I, Bateman LB, Oates GR. Systemic inflammation in midlife: race, socioeconomic status, and perceived discrimination. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(1S1):63–S76.

Ransing R, et al. Infectious disease outbreak related stigma and discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic: drivers, facilitators, manifestations, and outcomes across the world. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:555–8.

Dar SA, et al. Stigma in coronavirus disease-19 survivors in Kashmir, India: a cross-sectional exploratory study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(11):e0240152–2.

Chopra KK, Arora VK. Covid-19 and social stigma: role of scientific community. Indian J Tuberc. 2020;67(3):284–5.

Byrne P, James A. Placing poverty-inequality at the centre of psychiatry. BJPsych Bull. 2020;44(5):187–90.

Galea S, Abdalla SM. COVID-19 pandemic, unemployment, and civil unrest: underlying deep racial and socioeconomic divides. JAMA. 2020;324(3):227–8.

Liu S, et al. Increased psychological distress, loneliness, and unemployment in the spread of COVID-19 over 6 months in Germany. Med (Kaunas Lithuania). 2021;57(1):53.

Arora T, et al. The prevalence of psychological consequences of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Health Psychol. 2022;27(4):805–24.

IDSA, Post. COVID/Long COVID. https://www.idsociety.org/covid-19-real-time-learning-network/disease-manifestations--complications/post-covid-syndrome/. Accessed on February 5, 2021.

Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon’s mechanical Turk: a New source of Inexpensive, yet High-Quality, data? Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6(1):3–5.

Litman L, Robinson J, Abberbock T. TurkPrime.com: a versatile crowdsourcing data acquisition platform for the behavioral sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2017;49(2):433–42.

Qualtrics Q. 2005: Provo, Utah, USA.

Kees J, et al. An analysis of Data Quality: professional panels, student subject pools, and Amazon’s mechanical Turk. J Advertising. 2017;46(1):141–55.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13.

Löwe B, et al. Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46(3):266–74.

Sveen J, Bondjers K, Willebrand M. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5: a pilot study. Eur J Psychotraumatology. 2016;7:30165–5.

Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2(4):297–307.

Lee EH. Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nurs Res. 2012;6(4):121–7.

Derogatis LR, Rickels K, Rock AF. The SCL-90 and the MMPI: a step in the validation of a new self-report scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1976;128:280–9.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals. 2002;32(9):509–15.

Spitzer RL, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7.

Using the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp. Accessed on January 29, 2021.

Morin CM, et al. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34(5):601–8.

Gagnon C, et al. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(6):701–10.

Cohen S. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. The social psychology of health. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc; 1988. pp. 31–67.

Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Covi L. SCL-90: an outpatient psychiatric rating scale–preliminary report. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1973;9(1):13–28.

Nelson DE, et al. Reliability and validity of measures from the behavioral risk factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). Soz Praventivmed. 2001;46(Suppl 1):3–42.

Saunders JB, et al. Development of the Alcohol Use disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol Consumption–II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804.

Simons D, et al. The association of smoking status with SARS-CoV-2 infection, hospitalization and mortality from COVID-19: a living rapid evidence review with bayesian meta-analyses (version 7). Addiction. 2021;116(6):1319–68.

Pijls BG, et al. Demographic risk factors for COVID-19 infection, severity, ICU admission and death: a meta-analysis of 59 studies. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1):e044640.

Khanijahani A, et al. A systematic review of racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in COVID-19. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20(1):248.

Alegría M, et al. Social Determinants of Mental Health: where we are and where we need to go. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20(11):95–5.

Smith PH, Mazure CM, McKee SA. Smoking and mental illness in the U.S. population. Tob Control. 2014;23(e2):e147–53.

Brotto LA, et al. The influence of sex, gender, age, and ethnicity on psychosocial factors and substance use throughout phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0259676. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259676.

Leong A, et al. Cardiometabolic risk factors for COVID-19 susceptibility and severity: a mendelian randomization analysis. medRxiv: Preprint Serv Health Sci. 2020. 2020.08.26.20182709.

Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and conditional process analysis. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford; 2018.

Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991.

People with Certain Medical Conditions. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html. Accessed February 25, 2022.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988.

Xiong Q, et al. Clinical sequelae of COVID-19 survivors in Wuhan, China: a single-centre longitudinal study. Clin Microbiol Infection: Official Publication Eur Soc Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;27(1):89–95.

Huang L, et al. 1-year outcomes in hospital survivors with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2021;398(10302):747–58.

Orrù G, et al. Long-COVID syndrome? A study on the persistence of neurological, psychological and physiological symptoms. Healthc (Basel Switzerland). 2021;9(5):575.

Badenoch JB, et al. Persistent neuropsychiatric symptoms after COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Commun. 2021;4(1):fcab297–7.

Taquet M, et al. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(5):416–27.

Al-Aly Z, Xie Y, Bowe B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature. 2021;594(7862):259–64.

Rogers JP, et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(7):611–27.

Tansey CM, et al. One-year outcomes and Health Care Utilization in survivors of severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(12):1312–20.

Hayes LD, Ingram J, Sculthorpe NF. More than 100 persistent symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 (long COVID): a scoping review. Front Med. 2021; 8.

Sze S, et al. Ethnicity and clinical outcomes in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29:100630–0.

Xie Y, Bowe B, Al-Aly Z. Burdens of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 by severity of acute infection, demographics and health status. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):6571–1.

Saeed F, et al. A narrative review of Stigma related to Infectious Disease outbreaks: what can be learned in the Face of the Covid-19 pandemic? Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:565919–9.

Ross CE, Wu CL. Education, age, and the cumulative advantage in health. J Health Soc Behav. 1996;37(1):104–20.

Zajacova A, Lawrence EM. The Relationship between Education and Health: reducing disparities through a Contextual Approach. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39(1):273–89.

Faulkner J, et al. Physical activity, mental health and well-being of adults during initial COVID-19 containment strategies: a multi-country cross-section. Al Anal J Sci Med Sport. 2021;24(4):320–6.

Głąbska D, et al. Fruit and Vegetable Intake and Mental Health in adults: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2020;12(1):115.

Ozbay F et al. Social support and resilience to stress: from neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont (Pa: Township)). 2007;(5):35–40.

Becerra X. Annual Update of the HHS Poverty Guidelines. 2022; https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/01/21/2022-01166/annual-update-of-the-hhs-poverty-guidelines. Accessed March 1, 2022.

Whitaker M, et al. Persistent COVID-19 symptoms in a community study of 606,434 people in England. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1957.

Geyer S, et al. Education, income, and occupational class cannot be used interchangeably in social epidemiology. Empirical evidence against a common practice. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(9):804–10.

Iob E, Steptoe A, Zaninotto P. Mental health, financial, and social outcomes among older adults with probable COVID-19 infection: a longitudinal cohort study. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(27):e2200816119.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employment Situation Summary. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.nr0.htm. Accessed March 1, 2022.

Gilbert R, et al. Misclassification of outcome in case–control studies: methods for sensitivity analysis. Stat Methods Med Res. 2014;25(5):2377–93.

Thomason ME et al. Social determinants of health exacerbate disparities in COVID-19 illness severity and lasting symptom complaints. medRxiv: Preprint Serv Health Sci 2021; p. 2021.07.16.21260638.

Assari S, Social Determinants of Depression. The intersections of race, gender, and Socioeconomic Status. Brain Sci. 2017;7(12):156.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Declarations of Interest

None.

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) Institutional Review Board.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Statement Regarding Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Williams, M.K., Crawford, C.A., Zapolski, T.C. et al. Longer-Term Mental Health Consequences of COVID-19 Infection: Moderation by Race and Socioeconomic Status. Int.J. Behav. Med. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-024-10271-9

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-024-10271-9