Abstract

Peer, teacher, and self-feedback have been widely applied in English writing courses in higher education. However, few studies have used technology to activate the potential of feedback in project-based collaborative learning or discussed how technology-enhanced peer, teacher and self-feedback may assist students’ writing, promote their critical thinking tendency, or enhance their engagement in learning, so we investigated them in this research. A total of 90 students, 30 in each group, participated in it. They reported their progress at four stages every other week, received peer, teacher, and self-feedback respectively for 10 weeks, and submitted their finalized review articles in week 14. Before the treatment, we evaluated the students’ writing proficiency and critical thinking tendency through a pre-test and a pre-questionnaire survey. After the treatment, we evaluated their collaborative writing products and conducted a post-questionnaire survey to measure their critical thinking tendency and behavioral, cognitive, and emotional engagement in learning. The results indicated that technology-enhanced peer and teacher feedback were significantly more effective than self-feedback in assisting collaborative writing; peer and self-feedback were significantly more effective than teacher feedback in promoting critical thinking tendency, enhancing behavioral and emotional engagement in learning; and teacher feedback was significantly more effective than self-feedback in enhancing cognitive engagement in learning. We also conducted semi-structured interviews to investigate their perception of the three feedback types and the technology-enhanced feedback-assisted collaborative writing experience. Most students enjoyed the writing experience and regarded the use of digital tools effective for its implementation. Based on these results, we suggest that teachers implement more technology-enhanced peer and self-feedback assisted collaborative writing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Teacher feedback, as the dominant type of feedback on writing, has been widely regarded as effective in developing English as a second language (ESL) and English as a foreign language (EFL) students’ writing proficiency (Cui et al., 2021). ESL and EFL students also tend to show generally favorable attitudes towards teacher feedback (Zhao, 2010). However, university teachers normally have large class sizes or several groups of students. Meanwhile, providing feedback on the writing assignments for higher education requires more than just correcting grammar errors, so the workload of providing teacher feedback on writing in higher education is heavy. Consequently, teachers may not be able to provide detail feedback to every student, and the students who do not fully understand the feedback may benefit little from it (Ho et al., 2020; Lee, 2007). Considering that higher education students should be able to conduct quality peer and self-assessment and provide useful feedback (Lu et al., 2021; Peterson & McClay, 2010), educators and researchers tend to become increasingly interested in peer and self-feedback as alternatives for the writing classrooms in higher education.

Peer feedback emphasizes student engagement with feedback (Carless & Boud, 2018). In peer feedback assisted writing, students not only evaluate their peers’ writing and provide suggestions and comments but also actively act on the feedback they receive and revise their writing accordingly (Ajjawi & Boud, 2017). In this way, peer feedback activates the student role in learning, promotes self-regulated learning, and develops their critical thinking tendency (Winstone & Boud, 2019; Yu & Liu, 2021). In academic writing contexts, peer feedback can also help students learn from each other, so it has gain increasing popularity in higher education (Yu & Liu, 2021; López-Pellisa et al., 2021) examined peer feedback in collaborative writing and found that students were able to respond to peer feedback reflectively and constructively, thereby their writing performance was enhanced.

In self-feedback assisted writing, students reflect upon their own writing, comment on it according to the rubrics or assessment criteria, and then revise it based on their self-generated suggestions (Wakefield et al., 2014). Self-feedback activities can help students understand the writing requirements and grading criteria, evaluate their writing against the requirements and criteria, and consequently lead to writing proficiency development (Lu et al., 2021).

However, little research has been conducted to investigate technology enhanced peer, teacher, and self-feedback assisted writing, and most previous studies were of short-term. Moreover, few studies have discussed how they may assist students’ project-based collaborative writing, so we investigated them in this research that lasted for one semester. Specifically, we compared technology-enhanced peer, teacher, and self-feedback in three dimensions: (1) their effectiveness in assisting students’ collaborative writing of review articles, (2) their effectiveness in promoting students’ critical thinking tendency, and (3) their effectiveness in enhancing students’ behavioral, cognitive, and emotional engagement in learning. We also discussed whether students considered technology-enhanced peer, teacher, and self-feedback helpful and what they appreciated. The results indicated that technology-enhanced peer and teacher feedback were significantly more effective than self-feedback in assisting collaborative writing; peer and self-feedback were significantly more effective than teacher feedback in promoting critical thinking tendency, enhancing behavioral and emotional engagement in learning; and teacher feedback was significantly more effective than self-feedback in enhancing cognitive engagement in learning. Students enjoyed the technology enhanced feedback-assisted collaborative writing experience and regarded the use of digital tools effective for its implementation. Thus, we suggest that teachers implement more technology enhanced feedback-assisted collaborative writing in writing classes in higher education.

Literature review

Peer, teacher, and self-feedback assisted writing

Some studies have compared teacher and peer feedback. Zhang and McEneaney (2020) found that students who received peer feedback outperformed those who received teacher feedback in writing. Cui et al., (2021) found that untrained peer reviewers provided more meaning-focused feedback than teachers, while the trained peer reviewers gave more meaning-related comments than teachers. Thus, it seemed that with proper training, students could provide effective feedback, which could reduce teachers’ workload. Ruegg (2018) also investigated the impact of teacher and peer feedback on students’ writing self-efficacy, and the results indicated that students who received teacher feedback had higher self-efficacy than those who received peer feedback. This is perhaps because teachers provided more constructive feedback than peers, and self-efficacy was positively related to the exposure of feedback.

Concerning the effectiveness of self-feedback, Ramírez Balderas & Guillén Cuamatzi (2018) found that peer correction and self-correction had positive effects on students’ writing. Self-correction helped to raise students’ awareness about their errors, while peer correction gave students opportunities to confirm what was right or wrong. Both strategies helped to develop students’ critical thinking skills. Elfiyanto et al. (2021) provided Indonesian and Japanese students with peer, teacher, and self-feedback and found that peer feedback benefited Indonesian students most, whereas teacher feedback benefited Japanese students most. A possible reason might be that the students doubted their monitoring and evaluation abilities and appreciated teacher and peer feedback more. Yu et al., (2020) also examined the effects of feedback on students’ motivation and engagement and found positive effects of peer and self-feedback.

Critical thinking tendency

Critical thinking refers to a reasonable reflective approach to thinking, and it aims to “establish clear and logical connections between beginning premises, relevant facts and warranted conclusions” (Ivie, 2001, p. 10). With better critical thinking skills, students can achieve higher academic performance, participate more actively in social and academic activities, make wiser decisions, and obtain better jobs (Stupple et al., 2017). Thus, cultivating critical thinkers is a paramount goal of higher education.

Some researchers argued that critical thinking competence can be developed by using technologies and information, engaging in independent thinking, and solving problems (Johnson et al., 2010; Şendağ & Odabaşı, 2009). So, it is important to engage students in learning activities that involve the use of technologies and information and require problem-solving and decision-making (Sung et al., 2015). Some researchers found that conducting peer assessment and providing peer feedback can develop students’ critical thinking awareness and tendency (Joordens et al., 2009; Topping, 2009; Wang et al., 2017). As participating in technology enhanced project-based collaborative writing and conducting self-feedback also involves such practices as using technologies and information, solving problems, and making decisions, it is likely that they may also lead to the development of students’ critical thinking tendency.

Engagement in learning

Engagement in learning consists of three aspects, behavioral, cognitive, and emotional engagement (Elmaadaway, 2018). Behavioral engagement involves actively participating in learning activities, paying attention to the instructional content, and completing assignments (Furrer & Skinner, 2003; Zimmerman, 2000). Cognitive engagement involves attempting to apply knowledge into practices, acquiring new knowledge, and asking questions (Elmaadaway, 2018). Emotional engagement focuses more on the feelings and emotions, and it involves enjoying the learning contents and activities (Jamaludin & Osman, 2014). Engagement is a multidimensional construct and plays a role in enhancing students’ learning experience (Fredricks et al., 2004).

As previous studies on peer, teacher, and self-feedback assisted writing are limited in that they have discussed little the effects of technology enhanced peer, teacher, and self-feedback on students’ project-based collaborative writing, critical thinking tendency, and engagement in learning, we investigated them in this research. Our research questions are listed as follows.

-

1)

Was technology enhanced peer, teacher, and self-feedback similarly effective in assisting students’ collaborative writing of review articles, promoting their critical thinking tendency, and enhancing their behavioral, cognitive, and emotional engagement in learning?

-

2)

Did students consider technology enhanced peer, teacher, and self-feedback helpful? What did they appreciate during the writing process?

Method

A total of 90 master students participated in the research. The experiment procedure is illustrated in Fig.1. In week 1, the authors introduced the project and explained its purposes and requirements to the participants. In week 2, we conducted a diagnostic writing assessment and a pre-questionnaire survey to evaluate the participants’ writing proficiency and critical thinking tendency. Starting from week 3, the students worked in groups via online learning platforms to conduct reviews on self-selected educational issues and write review articles collaboratively. They reported their progress at five stages and received feedback on them using Google Docs and Flipgrid. In week 4, the participants shared their topics; in week 6, their review foci; in week 8, what articles and books they selected for the reviews and how they evaluated them; in week 10, their main findings and evidence; and in week 12, their initial drafts. The three groups of students received peer, teacher, and self-feedback respectively five times. In week 14, they finalized their review articles. We also conducted a post-questionnaire survey to measure their critical thinking tendency and behavioral, cognitive, and emotional engagement in learning and semi-structured interviews to investigate their perceptions of the three feedback types and the technology enhanced feedback-assisted collaborative writing experience.

Participants

The 90 participants, 18 males and 72 females, were students of a Master of Education program at a local university in Hong Kong. Their ages ranged from 22 to 24, and their majors were all related to education, for example, educational studies, early childhood education, educational and developmental psychology, and curriculum, teaching and assessment. The participants were randomly assigned to three groups. This course taught knowledge and skills of English for academic purposes. The lecturer was one of the authors. She has ten years of experience in teaching English for academic purposes. All students voluntarily participated in the project, and there was no conflict of interest.

The participants’ recent valid IELTS (International English Language Testing System) scores ranged from 6.5 to 7.0. We also evaluated their writing proficiency before the experiment with a diagnostic writing assessment. The results of the statistical analysis of the participants’ scores in IELTS and their performance in the diagnostic writing assessment indicated that no significant differences existed in their overall English proficiency and writing proficiency.

We also conducted a pre-questionnaire survey to examine their critical thinking tendency before the experiment. The results suggested that all students shared similar critical thinking tendency.

Procedure of the technology enhanced feedback-assisted collaborative writing

The participants were asked to work in groups of three or four members and complete literature review projects on self-selected topics. They reported their progress at five stages and received feedback on them every other week.

The researchers selected Google Docs and Flipgrid as the tools for students to share progress of their review projects due to three reasons. Firstly, they were easy-to-use and convenient, and their interfaces were user-friendly. Students could head to the two online platforms using their personal computers or install the applications on their tablets or mobile phones. They could use them anywhere anytime. Secondly, with Google Docs, students could share their writing drafts; and with Flipgrid, students could verbally explain their ideas with visual aids (e.g., drafts in Google Docs, discussion notes, PowerPoint) and shoot videos for sharing. A synthesis of both enabled students to easily report their progress, detail what their decisions were, and visualize and explain their decision-making processes. Thirdly, with Google Docs, feedback providers could directly comment on the writing drafts; and with Flipgrid, feedback providers could comment on the videos with either text or video comments. A synthesis of both afforded feedback on not only the writing drafts but also the progress sharing videos in both text and video comments.

In stage 1 (from week 3 to week 4), students selected topics based on their interests and narrowed them down. In week 4, they shared their topics in Google Docs and explained why they considered the topics important in Flipgrid. Subsequently, they received feedback on their topics from peers or the teacher or conducted self-evaluation within their groups and provided intra-group self-feedback. The feedback focused on whether the topics were interesting, important, not too broad, not too vague, and not too narrow. Based on the feedback, students improved their topics.

In Stage 2 (from week 5 to week 6), students searched and read articles on their selected topics and decided their review foci. In week 6, they reported what their review foci were and explained why they decided to focus on these aspects of the topics in Google Docs and Flipgrid. The feedback focused on whether the review foci were important and could add new knowledge to the understanding of the topics. Based on the feedback, students improved their review foci.

In Stage 3 (from week 7 to week 8), students searched, read, and selected articles and books for the reviews based on their review foci. In week 8, they shared what articles and books they selected, why they selected them, what their main contents were, and how they evaluated them in Google Docs and Flipgrid. The feedback focused on whether the selected articles and books were relevant and whether the evaluations were critical and well-justified. Based on the feedback, students improved their article selections and evaluations.

In Stage 4 (from week 9 to week 10), students list, evaluate, group, and organize their main findings and the associated evidence. In week 10, they reported the findings and evidence in Google Docs and Flipgrid. The feedback focused on whether the findings and evidence were relevant, original, logical, and critical. Based on the feedback, students improved their presentation and organization of the findings and evidence.

In Stage 5 (from week 11 to week 12), students drafted their initial version of the review articles. In week 12, they shared the drafts in Google Docs and the associated explanations in Flipgrid. The feedback focused on the content, organization, language, and conventions of the drafts. Based on the feedback, students improved their initial drafts.

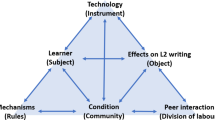

In sum, as illustrated in Fig.2, the three groups of students received technology-enhanced peer, teacher, and self-feedback respectively five times from week 3 to week 12. Based on the feedback, they improved their topics, review foci, selections of articles and books to review, main findings and evidence, and initial drafts. They finalized their review articles in week 14.

Instruments

The grading criteria of the review articles were adapted from Zou and Xie (2019). Four aspects were evaluated, including content, organization, language, and conventions. The maximum score of a review article was 100, 25 for each aspect. For the content, the review articles were evaluated from the perspectives such as to what extent the arguments and viewpoints were appropriately supported, to what extent the supporting evidence was relevant, and to what extent the analysis was logical. For the organization, the review articles were evaluated in terms of their cohesion, coherence, and the use of cohesive devices. For the language, the review articles were evaluated from three main perspectives: to what extent they were grammatically accurate, to what extent diverse grammatical structures and vocabulary were used, and to what extent the style and tone were appropriate. For the conventions, the layout, format, and referencing of the review articles were examined. The researchers focused on these four aspects as they were widely regarded as important for the evaluation of students’ writing (McDonough & De Vleeschauwer, 2019; Zou & Xie, 2019).

The questionnaire of critical thinking tendency, adapted from Chai et al., (2015), included six items. Sample items include “During the learning process, I would evaluate different opinions to see which one is more reasonable.”, “During the learning process, I will evaluate whether the viewpoints are supported by evidence.”, and “During the learning process, I will try to understand what I have learned from different perspectives.”. The Cronbach’s alpha value of this questionnaire was higher than 0.7, showing acceptable reliability (Chang & Hwang, 2018).

The questionnaire of engagement in learning, adapted from Elmaadaway (2018), included 25 items. There were 10 items concerning behavioral engagement in learning, examples of which include “I strive to understand the instructional content.”, “I ask questions about what I do not understand.”, and “I always complete my assignments.”. It also included seven items concerning cognitive engagement in learning, examples of which include “I attempt to apply things that I have learned.” and “I strive to acquire new knowledge about the course.”. Moreover, it included eight items concerning emotional engagement in learning, examples of which include “I enjoy the lectures.”, “Participating in the learning activities boosts my confidence.”, and “Sharing what I have learned is enjoyable.”. The Cronbach’s alpha value of the whole questionnaire was 0.95, and those of the three sub-sections were respectively 0.88, 0.90, and 0.87, indicating acceptable reliability (Chien & Hwang, 2021).

The wordings of the items for the two questionnaires were slightly modified based on the context of this research to ensure that the participants could easily understand the items, relate to their learning experience and perceptions, and precisely indicate to what extent they agreed with the statements. A 5-point Likert scale was used for both questionnaires, with 1 representing “strongly disagree” and 5 representing “strongly agree”.

The semi-structured interview included six sets of guided questions. The participants were prompted to reflect on their learning experience and express their opinions in either Chinese or English, as they preferred. The questions are listed as follows. (1) To what extent do you agree that the peer feedback (or teacher or self-feedback, depending on what feedback the participants received) can help you collect ideas for writing? Why? (2) To what extent do you agree that the feedback can help you organize the ideas? Why? (3) To what extent do you agree that the feedback can help your initial writing of the review articles? Why? (4) To what extent do you agree that the feedback can help your revision of the review articles? Why? (5) Do you enjoy learning with this approach to writing (i.e., peer/ teacher/ self-feedback-assisted collaborative writing)? What do you like or dislike? Why? (6) Overall, to what extent do you agree that you have benefited from this technology enhanced feedback-assisted collaborative writing experience? How do you evaluate this learning process and learning experience? Why?

Data collection and analysis

The researchers collected and analyzed five main types of data. Firstly, we scored students’ diagnostic writing essays and their final review articles based on the grading criteria and obtained the data of their prior writing proficiency and their feedback-assisted collaborative writing performance. Two experienced English teachers scored the writings based on Zou and Xie’s (2019) grading criteria independently. The Pearson’s r for the interrater reliability was 0.92. for the diagnostic writing essays and 0.94 for the review articles. Secondly, we conducted pre- and post-questionnaire surveys to collect data of students’ critical thinking tendency before and after the experiment. Thirdly, we conducted a post-questionnaire survey to collect data of students’ behavioral, cognitive, and emotional engagement in learning. We entered these three types of data into SPSS and analyzed them by running statistical analysis.

Fourthly, we interviewed the students to collect data of their perceptions of peer, teacher, and self-feedback and the feedback-assisted collaborative writing experience. Fifthly, Google Docs and Flipgrid recorded the data concerning how students improved their topics, review foci, selections and evaluations of the reviewed articles and books, presentation and organization of the findings and evidence, and the initial drafts based on the feedback they received. We analyzed these two types of data based on Braun and Clarke’s guidelines of thematic analysis (2006). After familiarizing with the data, we generated initial codes (e.g. perceptions of the received feedback and associated follow-ups), grouped relevant data into potential themes (e.g. evaluations of the feedback and intentions of revising one’s writing based on the feedback), and reviewed them several times. We then defined and named the themes (e.g. types and depth of critical thinking triggered by the feedback and engagement in the feedback) and produced the results.

Results

Effectiveness in assisting collaborative writing

The results of tests of normality showed that the three groups of participants’ scores in the diagnostic writing assessment and the collaborative writing project were all normally distributed and shared homogeneous variances. There were also no significant outliers, and the data met the requirement of independence of observations. Thus, we analyzed the data using one-way analysis of covariance (one-way ANCOVA) to test whether statistically significant differences existed, after controlling for the participants’ diagnostic writing scores.

Table2 presents the results of the students’ performance in the technology enhanced feedback-assisted collaborative writing. The students who learned with teacher feedback achieved the best performance (M = 88.13, SD = 5.40), followed by peer feedback (M = 85.50, SD = 6.74); and those who learned with self-feedback had the lowest scores (M = 81.13, SD = 6.15). The results of the univariate tests, as shown in Table3, indicate that the three types of feedback were significantly different in assisting collaborative writing (F(2,86) = 9.92, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.19).

Additionally, the results of the pairwise comparisons, as presented in Table4, indicated that both peer and teacher feedback were significantly more effective than self-feedback in assisting students’ collaborative writing. No significant difference existed between peer and teacher feedback in assisting students’ collaborative.

Effectiveness in promoting critical thinking tendency

The results of tests of normality showed that the three groups of participants’ critical thinking tendency before and after their technology enhanced feedback-assisted collaborative writing experience were all normally distributed and shared homogeneous variances. There were also no significant outliers, and the data met the requirement of independence of observations. Thus, we analyzed the data using one-way ANCOVA to test whether statistically significant differences existed, after controlling for the participants’ critical thinking tendency before the experiment.

Table5, which presents the results of the students’ critical thinking tendency, showed that the students who learned with peer feedback (M = 4.27, SD = 0.41) had higher critical thinking tendency than those who learned with self-feedback (M = 4.16, SD = 0.40). The students who learned with teacher feedback (M = 3.52, SD = 0.43) had the lowest critical thinking tendency. The results of the univariate tests, as shown in Table6, indicate that the three types of feedback were significantly different in assisting collaborative writing (F(2,86) = 28.41, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.39).

Concerning the effectiveness in promoting students’ critical thinking tendency, the results of the pairwise comparisons indicated that both peer and self-feedback were significantly more effective than teacher feedback (see Table7). No significant difference existed between peer and self-feedback in promoting students’ critical thinking tendency.

Effectiveness in enhancing behavioral, cognitive, and emotional engagement in learning

The results of tests of normality showed that the three groups of participants’ behavioral, cognitive, and emotional engagement in learning were all normally distributed and shared homogeneous variances. There were also no significant outliers, and the data met the requirement of independence of observations. Thus, we analyzed the data using one-way MANOVA to test whether statistically significant differences existed among the three types of feedback.

Table8 presents the group means and standard deviations of the three types of feedback in enhancing students’ behavioral, cognitive, and emotional engagement in learning. From the perspective of behavioral engagement, peer feedback (M = 4.22, SD = 0.57) was more effective than self-feedback (M = 4.07, SD = 0.49), and teacher feedback was the least effective among the three (M = 3.60, SD = 0.46). From the perspective of cognitive engagement, teacher feedback (M = 4.09, SD = 0.42) was more effective than peer feedback (M = 3.90, SD = 0.41), and self-feedback was the least effective (M = 3.83, SD = 0.39). From the perspective of emotional engagement, peer feedback (M = 4.19, SD = 0.53) was more effective than self-feedback (M = 4.16, SD = 0.41), and teacher feedback was the least effective among the three (M = 3.72, SD = 0.47).

Moreover, the results of the multivariate tests indicated that there was a statistically significant difference in the three groups of participants’ engagement in learning, F(6, 170) = 5.81, p < 0.05; Wilk’s Λ = 0.68, partial η2 = 0.17. Table9 presents the results of the tests of between-subjects effects of engagement in learning. Specifically, significant differences existed among the three types of feedback in enhancing students’ behavioral engagement (F = 11.74, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.21), cognitive engagement (F = 3.21, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.07), and emotional engagement in learning (F = 9.18, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.17).

Table10 shows the results of the multiple comparisons of the three groups of students’ engagement in learning. From the perspective of behavioral engagement, (1) both peer and self-feedback were significantly more effective than teacher feedback, and (2) peer and self-feedback were similarly effective. From the perspective of cognitive engagement, (3) teacher feedback was significantly more effective than self-feedback, (4) teacher and peer feedback were similarly effective, and (5) peer and self-feedback were similarly effective. From the perspective of emotional engagement, (6) both peer and self-feedback were significantly more effective than teacher feedback, and (7) no significant differences existed between peer and self-feedback.

Learner perceptions of the technology enhanced feedback-assisted collaborative writing

Concerning the students’ perceptions of peer, teacher, and self-feedback and their technology-enhanced feedback-assisted collaborative writing experience, the interview data indicated four main findings. Firstly, almost all students agreed that they had benefited a lot from this technology enhanced feedback-assisted collaborative writing experience. They felt that they had learned how to search for relevant information to build up their writing ideas, how to evaluate their arguments, viewpoints, and supporting evidence, and how to organize their findings and evidence. Most students described this technology enhanced feedback-assisted collaborative writing experience as “beneficial,” “very helpful,” “useful for writing skill development,” “interesting,” “fun,” and “interactive.” Several students even commented that “this is the best writing activity that I have ever had.”, “I would love to have more similar writing activities in future.”, and “I start to love writing because of this writing experience.”

Secondly, most students regarded the use of digital tools (i.e., Google Docs and Flipgrid) effective for the implementation of feedback-assisted collaborative writing. Many students commented that this technology enhanced approach to providing and receiving feedback enriched the learning activity, smoothed the learning process, and enabled them to obtain useful information easily and conveniently when necessary. They described the use of digital tools as “smart,” “convenient,” “having enhanced the learning experience,” and “having made it (participating in the collaborative writing and providing and receiving feedback) easy and convenient.”

Thirdly, almost all students in the peer and self-feedback groups appreciated the experience of evaluating their peers’ or their own topics, review foci, selections and evaluations of the reviewed articles and books, presentation and organization of the findings and evidence, and the initial drafts. Most students felt that the experience of judging their peers’ or their own writing ideas and organization promoted their critical thinking and enhanced their learning engagement. Many students described the learning process as “enjoyable,” “creative,” “interactive,” “effective in involving every student in the learning activity,” and “effective in promoting critical thinking.”

Fourthly, many students in the teacher feedback group felt that they benefited a lot from teacher feedback in terms of improving their presentation and organization of the findings and evidence and revising their initial drafts. They reported that teacher feedback helped them realize the limitations of their writing. These limitations were mostly beyond their writing and thinking abilities, so many students admitted that they would hardly notice these limitations without teacher feedback. Most students also admitted that they basically tended to follow teacher feedback directly, rather than further asked themselves why the teacher suggested them to revise the writing in this way, as they believed in the teacher’s professional knowledge and felt it easy to follow the teacher but not so necessary to question why. Many students described the experience of teacher feedback-assisted collaborative writing as “beneficial,” “effective in improving the writing ideas and drafts,” “having learned a lot about organizing writing ideas,” “having benefited much in terms of using evidence to support arguments,” and “effective in developing writing skills.”

Discussion

Effectiveness of the technology enhanced feedback-assisted collaborative writing

The statistical analysis results of the students’ performance in the technology enhanced feedback-assisted collaborative writing indicated that both peer and teacher feedback were significantly more effective than self-feedback. The interview data also suggested that many students in the self-feedback group pointed out that they could hardly identify the limitations of their own selections and evaluations of the reviewed articles and books. They also found it difficult to provide themselves suggestions on how to improve their presentation or organization of the review findings or evidence. Thus, they received limited guidance concerning the improvement of their writing ideas and organization. These results were consistent with the findings of Elfiyanto & Fukazawa (2021), which suggested that self-feedback seemed less effective than teacher or peer feedback.

Moreover, the data as recorded in Google Docs and Flipgrid showed that the students who learned with self-feedback conducted much fewer feedback-based major changes than those who received peer and teacher feedback. Their intra-group self-evaluation also suggested fewer major revisions. Yet peer and teacher feedback included much more criticism and requirements concerning the necessity of including more evidence to support different viewpoints and explaining how a conclusion was reached. Thus, it seems that one main limitation of self-feedback was its lack of helpful suggestions for students’ improvement of the content and organization of their writing, while peer and teacher feedback provided abundant comments and suggestions.

It is also noteworthy that peer and teacher feedback were similarly effective in assisting students’ collaborative writing. This may be because they both could lead students to realize the problems of the content and organization of their writing, pay attention to them, attempt to solve them, and accordingly improve the writing, as indicated by the interview results. These findings add future support to Yang’s (2016, 2018) observations that the processes of making decisions on accepting or rejecting peer or teacher feedback during collaborative writing involved using various cognitive strategies, which led to improved writing. Thus, we suggest that peer feedback could be used as an effective alternative of teacher feedback in leading students to revisit and improve their writing.

Effectiveness of the technology enhanced feedback-assisted critical thinking

The statistical analysis results of the students’ critical thinking tendency indicated that both peer and self-feedback were significantly more effective than teacher feedback. The interview results also suggested that students felt that the teacher had rich domain knowledge and expertise in teaching writing, so when they received teacher feedback, they rarely judged whether the feedback was appropriate. When they encountered a problem, they tended to wait for the teacher’s help, rather than strived to solve it by themselves and make deductions.

However, when students received peer feedback, they tended to evaluate whether it was reasonable and acceptable, compare different opinions to judge their value, and decide whether they would revise their writing based on the peer feedback and how to revise it. Similarly, when students conducted self-evaluation to produce intra-group self-feedback, they strived to think from different perspectives on what they had learned, judged whether their viewpoints and argument were supported by evidence, detected problems, justified them, and attempted to solve them. The data recorded in Google Docs and Flipgrid also showed that the students who learned with peer and self-feedback had many discussions concerning whether an argument was well-justified and whether a viewpoint was supported by evidence, indicating their attempts to think critically. Thus, peer and self-feedback could effectively promote students’ critical thinking tendency, and these results were aligned with the findings of Ramírez Balderas & Guillén Cuamatzi (2018). Similarly, Pham et al., (2020) found that providing and receiving feedback could guide learners to perform a variety of cognitive strategies and develop critical thinking skills, thus peer and self-feedback assisted learning was conducive to students’ critical thinking tendency development. According to Yu & Lee (2016), the effectiveness of feedback in promoting critical thinking to an extent depends on its degree of mutuality, and effective feedback ought to have moderate to high degrees of mutuality. The interview results of our research indicated that the use of educational technology increased the convenience of providing and receiving peer feedback, which led to increased degrees of mutuality. These might explain why technology-enhanced peer feedback tends to be effective in promoting critical thinking.

Engagement in the technology enhanced feedback-assisted collaborative writing

The research results suggested that students were behaviorally, cognitively, and emotionally engagement in the technology enhanced feedback-assisted collaborative writing. Google Docs and Flipgrid were two useful digital tools for the implementation of technology enhanced feedback-assisted collaborative writing, and the use of them contributed much to the effectiveness of feedback-assisted collaborative writing in promoting engagement in learning. Students could use either mobile phones or personal computers to access the mobile applications or websites of Google Docs and Flipgrid, so it was easy and convenient for them to participate in the collaborative writing and provide or receive feedback. This to a large extent led to the students’ behavioral engagement in learning.

Moreover, for the peer and self-feedback groups, the whole feedback-assisted collaborative writing process involved five rounds of decision-making and problem raising and solving, each of which required numerous discussion and negotiation for the peer feedback group or continuous self-challenging, evaluation, and problem solving for the self-feedback group. Thus, these two groups of students were fully occupied with the project-based learning, and in most cases, they asked questions about what they felt unclear or confused, strived to solve the problems, and were eager to contribute to the collaborative writing project. Therefore, peer and self-feedback were significantly more effective than teacher feedback in enhancing behavioral engagement. Yu et al., (2020) had similar findings.

However, from the perspective of enhancing students’ cognitive engagement, teacher feedback was significantly more effective than self-feedback. This is likely because students were more likely to trust teachers than themselves and feel that they could learn more from teacher feedback than self-feedback. Consequently, they were much more cognitively engaged in teacher feedback than self-feedback. The research also suggested that as students regarded their peers at similar levels with themselves, no significant differences existed between peer and self-feedback in this respect. Nevertheless, as peers could raise questions or point out problems as outsiders, students found peer feedback useful in helping them notice limitations of their selections and evaluations of the reviewed articles and books and improve their presentation or organization of the review findings or evidence. Thus, no significant differences existed between peer and teacher feedback in this respect.

From the perspective of enhancing students’ emotional engagement, peer and self-feedback involved more active learning than teacher feedback by means of student contribution to the collaborative writing project, as these two groups of students conducted five rounds of decision-making and problem raising and solving. Such practices helped students notice and solve problems, so they tended to gradually become increasingly confident and optimistic as the collaborative writing project proceeded and enjoyed the learning process much. Consequently, peer and self-feedback were significantly more effective than teacher feedback in emotionally engaging students.

Conclusion

In this study, we investigated the effects of technology enhanced peer, teacher, and self-feedback on students’ collaborative writing of review articles. Statistically significant differences existed among the three types of feedback in assisting students’ collaborative writing, promoting their critical thinking tendency, and enhancing their behavioral, cognitive, and emotional engagement in learning. Specifically, the statistical analysis results indicated that peer and teacher feedback were significantly more effective than self-feedback in assisting collaborative writing; peer and self-feedback were significantly more effective than teacher feedback in promoting critical thinking tendency, enhancing behavioral and emotional engagement in learning; and teacher feedback was significantly more effective than self-feedback in enhancing cognitive engagement in learning.

The interview results suggested that students enjoyed the technology enhanced feedback-assisted collaborative writing experience and regarded the use of digital tools effective for its implementation. Almost all students in the peer and self-feedback groups appreciated the experience of learning through providing and receiving feedback and reported that they had benefited greatly from it in respect of critical thinking tendency and engagement in learning. Many students in the teacher feedback group believed that teacher feedback was useful not only for their development and organization of writing ideas but also their improvement of the drafts. Moreover, teacher feedback could help them realize the limitations of their writing, which students appreciated most.

Based on these results, we suggest that teachers implement more technology enhanced feedback-assisted collaborative writing in writing classes in higher education. To enhance students’ learning experience, they can apply digital tools that afford convenient and easy access, for example, Google Docs and Flipgrid. We also encourage teachers to integrate more peer feedback and self-feedback assisted writing activities into their lecture plans as they can effectively promote students’ critical thinking tendency and enhance their engagement in learning. Lastly, we recommend project-based writing for higher education and promote integration of peer, teacher, and self-feedback into different stages of the writing process, as students appreciate the feedback-assisted writing and can benefit much from it in respect of the development and organization of their writing ideas and improvement of their drafts.

This research is however limited in five aspects. Firstly, the participants were students of a course in different cohorts. However, they shared similar IELTS scores, ages, and academic background, so the influences of learner factors on the research results seem small. Future studies may consider inviting students from the same cohort and applying random sampling in the research. Secondly, much fewer male students participated in the research than female students. Nevertheless, the proportions of males to females of the three groups are similar, so the possible influences of gender on the research results are unlikely to be big. Future research may consider balancing the male and female participants and discuss whether gender places potential influences on the technology enhanced feedback-assisted collaborative writing process and outcomes. Thirdly, the numbers of participants were limited, and fourthly, we only investigated their writing performance, critical thinking tendency, and engagement in learning. Future research may consider inviting more participants and investigating the effects of technology enhanced feedback-assisted collaborative writing on other aspects such as students’ motivation, self-efficacy, and cognitive load. Additionally, as several previous studies have discussed conventional feedback-assisted writing, this research focused mainly on the comparison of technology enhanced peer, teacher, and self-feedback in assisting students’ collaborative writing, promoting their critical thinking tendency, and enhancing their learning engagement. Thus, the differences between feedback-assisted writing without technology and technology-enhanced feedback are not within the scope of this research. A potential direction of the future research may be the in-depth analysis of the affordances and added value of technology for feedback-assisted collaborative writing process and outcomes.

References

Ajjawi, R., & Boud, D. (2017). Researching feedback dialogue: An interactional analysis approach. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(2), 252–265

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101

Carless, D., & Boud, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: enabling uptake of feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(8), 1315–1325. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

Chai, C. S., Deng, F., Tsai, P. S., Koh, J. H. L., & Tsai, C. C. (2015). Assessing multidimensional students’ perceptions of twenty-first-century learning practices. Asia Pacific Education Review, 16(3), 389–398

Chang, S. C., & Hwang, G. J. (2018). Impacts of an augmented reality-based flipped learning guiding approach on students’ scientific project performance and perceptions. Computers & Education, 125, 226–239

Chien, S. Y., & Hwang, G. J. (2021). A question, observation, and organisation-based SVVR approach to enhancing students’ presentation performance, classroom engagement, and technology acceptance in a cultural course. British Journal of Educational Technology. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13159

Cui, Y., Schunn, C. D., & Gai, X. (2021). Peer feedback and teacher feedback: A comparative study of revision effectiveness in writing instruction for EFL learners. Higher Education Research & Development, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1969541

Elfiyanto, S., & Fukazawa, S. (2021). Three written corrective feedback sources in improving Indonesian and Japanese students’ writing achievement. International Journal of Instruction, 14(3), 433–450

Elmaadaway, M. A. N. (2018). The effects of a flipped classroom approach on class engagement and skill performance in a blackboard course. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(3), 479–491. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12553

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74, 59–109

Furrer, C., & Skinner, E. (2003). Sense of relatedness as a factor in children’s academic engagement and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 148–161

Ho, P. V. P., Phung, L. T. K., Oanh, T. T. T., & Giao, N. Q. (2020). Should peer E-comments replace traditional peer comments? International Journal of Instruction, 13(1), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2020.13120a

Ivie, S. D. (2001). Metaphor: A model for teaching critical thinking. Contemporary Education, 72(1), 18

Jamaludin, R., & Osman, S. Z. (2014). The use of a flipped classroom to enhance engagement and promote active learning. Journal of Education and Practice, 5, 124–131

Joordens, S., Pare, D. E., & Pruesse, K. (2009). PeerScholar: An Evidence-based online peer assessment tool supporting critical thinking and clear communication. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on e-Learning (pp.236–240). Academic Conferences Limited

Johnson, T. E., Archibald, T. N., & Tenenbaum, G. (2010). Individual and team annotation effects on students’ reading comprehension, critical thinking, and meta-cognitive skills. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(6), 1496–1507

Lee, I. (2007). Feedback in Hong Kong secondary writing classrooms: Assessment for learning or assessment of learning? Assessing Writing, 12(3), 180–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2008.02.003

López-Pellisa, T., Rotger, N., & Rodríguez-Gallego, F. (2021). Collaborative writing at work: Peer feedback in a blended learning environment. Education and Information Technologies, 26(1), 1293–1310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10312-2

Lu, Q., Zhu, X., & Cheong, C. M. (2021). Understanding the difference between self-feedback and peer feedback: a comparative study of their effects on undergraduate students’ writing improvement. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 739962. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.739962

Peterson, S. S., & McClay, J. (2010). Assessing and providing feedback for student writing in Canadian classrooms. Assessing writing, 15(2), 86–99

Ramírez Balderas, I., & Guillén Cuamatzi, P. M. (2018). Self and peer correction to improve college students’ writing skills. Profile: Issues in Teachers´ Professional Development, 20(2), 179–194. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v20n2.67095

Pham, T. N., Lin, M., Trinh, V. Q., & Bui, L. T. P. (2020). Electronic peer feedback, EFL academic writing and reflective thinking: Evidence from a Confucian context. Sage Open, 10(1), 2158244020914554. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020914554

Ruegg, R. (2018). The effect of peer and teacher feedback on changes in EFL students’ writing self-efficacy. The Language Learning Journal, 46(2), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2014.958190

Şendağ, S., & Odabaşı, H. F. (2009). Effects of an online problem based learning course on content knowledge acquisition and critical thinking skills. Computers & Education, 53(1), 132–141

Stupple, E. J., Maratos, F. A., Elander, J., Hunt, T. E., Cheung, K. Y., & Aubeeluck, A. V. (2017). Development of the Critical Thinking Toolkit (CriTT): A measure of student attitudes and beliefs about critical thinking. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 23, 91–100

Sung, H. Y., Hwang, G. J., & Chang, H. S. (2015). An integrated contextual and web-based issue quest approach to improving students’ learning achievements, attitudes and critical thinking. Educational Technology & Society, 18(4), 299–311

Topping, K. (2009). Peer assessment. Theory into Practice, 48(1), 20–27

Wakefield, C., Adie, J., Pitt, E., & Owens, T. (2014). Feeding forward from summative assessment: The essay feedback checklist as a learning tool. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 39(2), 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2013.822845

Wang, X. M., Hwang, G. J., Liang, Z. Y., & Wang, H. Y. (2017). Enhancing students’ computer programming performances, critical thinking awareness and attitudes towards programming: An online peer-assessment attempt. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 20(4), 58–68

Winstone, N., & Boud, D. (2019). Exploring cultures of feedback practice: the adoption of learning-focused feedback practices in the UK and Australia. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(2), 411–425

Yang, Y. F. (2016). Transforming and constructing academic knowledge through online peer feedback in summary writing. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 29(4), 683–702. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2015.1016440

Yang, Y. F. (2018). New language knowledge construction through indirect feedback in web-based collaborative writing. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 31(4), 459–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2017.1414852

Yu, S., Jiang, L., & Zhou, N. (2020). Investigating what feedback practices contribute to students’ writing motivation and engagement in Chinese EFL context: A large scale study. Assessing Writing, 44, 100451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2020.100451

Yu, S., & Lee, I. (2016). Exploring Chinese students’ strategy use in a cooperative peer feedback writing group. System, 58, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2016.02.005

Yu, S., & Liu, C. (2021). Improving student feedback literacy in academic writing: An evidence-based framework. Assessing Writing, 48, 100525

Zhang, X., & McEneaney, J. E. (2020). What is the influence of peer feedback and author response on Chinese university students’ English writing performance? Reading Research Quarterly, 55(1), 123–146. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.259

Zhao, H. (2010). Investigating learners’ use and understanding of peer and teacher feedback on writing: A comparative study in a Chinese English writing classroom. Assessing Writing, 15(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2010.01.002

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: a social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of Self-regulation (pp. 13–39). San Diego: Academic Press.Zou, D. & Xie, H. (2019). Flipping an English class with technology-enhanced just-in-time teaching and peer instruction. Interactive Learning Environments, 27(8), 1127-1142.

Acknowledgement

Dr.Zou’s research is supported by the Seed Funding Grant (RG64/21-22R) of The Education University of Hong Kong. Dr. Xie’s research is supported by the Blended Learning project entitled "Facilitating the experiential and peer-to-peer e-pedagogy via social learning" under "Advanced Blended Learning @ Lingnan to a New Stage” (project code: 202105) at Lingnan University, Hong Kong.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zou, D., Xie, H. & Wang, F. Effects of technology enhanced peer, teacher and self-feedback on students’ collaborative writing, critical thinking tendency and engagement in learning. J Comput High Educ 35, 166–185 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-022-09337-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-022-09337-y