Abstract

Introduction

This study compared the clinical effectiveness of switching from tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) to upadacitinib (TNFi-UPA), another TNFi (TNFi-TNFi), or an advanced therapy with another mechanism of action (TNFi-other MOA) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods

Data were drawn from the Adelphi RA Disease Specific Programme™, a cross-sectional survey administered to rheumatologists and their consulting patients in Germany, France, Italy, Spain, the UK, Japan, Canada, and the USA from May 2021 to January 2022. Patients who switched treatment from an initial TNFi were stratified by subsequent therapy of interest: TNFi-UPA, TNFi-TNFi, or TNFi-other MOA. Physician-reported clinical outcomes including disease activity (with formal DAS28 scoring available for 29% of patients) categorized as remission, low/moderate/high disease activity, as well as pain were recorded at initiation of current treatment and ≥ 6 months from treatment switch. Fatigue and treatment adherence were measured ≥ 6 months from treatment switch. Inverse-probability-weighted regression adjustment compared outcomes by subsequent class of therapy: TNFi-UPA versus TNFi-TNFi, or TNFi-UPA versus TNFi-other MOA.

Results

Of 503 patients who switched from their first TNFi, 261 were in TNFi-UPA, 128 in TNFi-TNFi, and 114 in TNFi-other MOA groups. At the time of switch, most patients had moderate/high disease activity (TNFi-UPA: 73%; TNFi-TNFi: 52%; TNFi-other MOA: 60%). After adjustment for differences in characteristics at point of switch, patients in TNFi-UPA group (n = 261) were significantly more likely to achieve physician-reported remission (67.7% vs. 40.3%; p = 0.0015), no pain (55.7% vs. 25.4%; p = 0.0007), and complete adherence (60.0% vs. 34.2%; p = 0.0049) compared with patients in TNFi-TNFi group (n = 121). Similar findings were observed for TNFi-UPA versus TNFi-other MOA groups (n = 111).

Conclusion

Patients who switched from TNFi to UPA had significantly better clinical outcomes of remission, no pain, and complete adherence than those who cycled TNFi or switched to another MOA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Prior research has demonstrated that switching to an advanced therapy with a different mechanism of action (MOA) may be more favorable than cycling through tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA); however, further research is required. |

This study aimed to compare the clinical effectiveness of switching from a first-line TNFi to upadacitinib (UPA) versus cycling through TNFis or switching to a drug with another MOA, among patients with RA. |

What was learned from the study? |

Patients with RA who switched from TNFi to UPA had significantly better clinical outcomes of remission, no pain, and complete adherence than those who cycled TNFi or those who switched to a drug with another MOA. |

These findings show that UPA may be an effective treatment option in patients with a primary non-response, secondary loss of response, or intolerance to TNFis. |

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by persistent synovitis and systemic inflammation [1, 2]. Poor disease control in RA can lead to disease progression and may be associated with increased risk of comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease and serious infection, as well as lower health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [1, 3,4,5]. Patients who achieve and maintain remission in RA have improved outcomes, including less pain, better physical functioning, and better HRQoL [6,7,8]. Clinical remission in RA has also been associated with less healthcare resource utilization and lower medical costs compared with those with higher disease activity levels [9, 10].

Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis) are often the first choice of targeted therapy for RA; however, many patients do not achieve treatment targets such as sustained remission or low disease activity (LDA) [11,12,13]. Approximately 30–40% of patients with RA discontinue treatment with TNFis due to primary failure, secondary loss of response, or intolerance [14]. Predictors of discontinuation include longer disease duration before treatment and concomitant use of glucocorticoids [15].

Although treatment guidelines for RA recommend a goal of remission, LDA can be an alternative goal for patients who are unable to achieve remission [12, 16]. Patients who experience primary non-response, secondary loss of response, or intolerances when taking a TNFi may consider cycling or switching to a medication with another mechanism of action (MOA) as an alternative treatment option [17, 18]. A prior meta-analysis and an economic evaluation demonstrated that switching to an advanced therapy (AT) with a different MOA may be more effective and less expensive than cycling through TNFis in patients with RA [19, 20]. Upadacitinib (UPA), a Janus kinase inhibitor (JAKi), has been recently approved for treatment of RA [21, 22] and there is, therefore, a paucity of real-world data surrounding its use and effectiveness. Thus, the aim of this study was to compare the clinical effectiveness of treatment switching in patients with RA, from TNFi to UPA (TNFi-UPA) versus cycling through TNFis (TNFi-TNFi) or switching from TNFi to other MOAs (TNFi-other MOA), including interleukin (IL)-6 receptor and B lymphocyte antigen CD20 (CD20) inhibitors or cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) co-stimulators.

Methods

Study Design and Patients

Data were drawn from the Adelphi RA Disease Specific Programme™ (DSP), a cross-sectional survey with elements of retrospective data collection administered to rheumatologists and their consulting patients in Germany, France, Italy, Spain, the UK), Japan, Canada, and the USA from June 2021 to February 2022. Orthopedists were included in Japan as they are heavily involved in the management and treatment of RA [23]. A complete description of the methodology has been previously described [24, 25], published [26], and validated [27], and has shown to be representative and consistent over time.

Rheumatologists completed a physician survey and then completed patient record forms (PRF) for the next 5–10 patients consulted in routine clinical practice. Patients for whom a PRF was completed were then invited to voluntarily complete a patient self-completion form. PRFs included information on patient demographics, RA diagnostic and treatment journey, disease activity, symptoms, management and treatment, concomitant conditions, and outcomes. Physicians were included if they were currently practicing as a rheumatologist (or an orthopedist in Japan), were actively involved in the management of patients with RA, making management decisions for ≥ 5 patients in a typical month, and were not recently qualified (≤ 1 year).

Patients were included if they had a physician confirmed diagnosis of RA, were ≥ 18 years of age, and were not participating in a clinical trial at the time of the survey.

The survey period continued until a quota of 5–10 patients was reached. The survey was fielded from June 2021 to January 2022 in Germany, France, Italy, Spain, the UK, and the USA; May 2021 to November 2021 in Canada; and September 2021 to January 2022 in Japan.

Physicians were also given the opportunity to complete a further 2–3 PRFs, reporting data for patients currently receiving UPA, to form an oversample. Given the recent approval of UPA in RA (between 2019 and 2021 in Europe [22], Japan [28], Canada [29], and the USA [21]), the oversample was carried out to ensure adequate sample size for analysis.

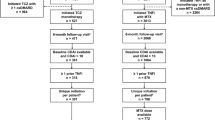

The population of interest for this study was patients with RA who were receiving a second line of AT at data collection for ≥ 6 months, having switched from an initial first line TNFi (n = 503); reasons for switching were reported. All patients were stratified by subsequent therapy of interest: TNFi-UPA (n = 261), TNFi-TNFi (n = 128), or TNFi-other MOA (n = 114). TNFi-TNFi excluded any patients who switched from originator to biosimilar for the same molecule. Patients with > 1 prior TNFi were also excluded.

Patient Demographics, Treatment History, and Clinical Characteristics

Patient demographic and treatment history information collected included patient age, biological sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), select cardiovascular (CV) risk factors (age ≥ 65 years, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, smoking status), time since diagnosis of RA, prior conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (csDMARD) use, prior corticosteroid use, time to first TNFi, TNFi received as first-line treatment, duration of TNFi use, reasons for switching from TNFi, and duration of current treatment.

Clinical characteristics included physician-reported disease activity (with formal DAS28 scoring available for 29% of patients) categorized as follows: remission, < 2.6; LDA, 2.6 to < 3.2; moderate disease activity [MDA], ≥ 3.2–5.1; and high disease activity [HDA], > 5.1 at initiation of current treatment and the most recent follow-up (≥ 6 months from treatment switch). Physician-reported pain (none, mild, moderate, or severe) was also recorded at initiation of current treatment (baseline) and at the most recent follow-up. In addition, physicians reported fatigue (none, mild, moderate, or severe) and physician-reported adherence to medication (completely adherent or not completely adherent), which were recorded at the most recent follow-up. Physician-reported outcomes of disease activity (DAS28 scores), pain, fatigue, and medication adherence at most recent follow-up (≥ 6 months after treatment initiation) were compared for TNFi-UPA versus TNFi-TNFi and TNFi-UPA versus TNFi-other MOA.

Physicians were instructed to refer to the patients’ medical records when completing their PRF to ensure the most up-to-date medical information was included. DAS28 was collected using objective DAS28 assessments performed at the consultation, from medical records (DAS28 assessments performed within 4 weeks prior), or when neither of these was available, from the physician’s own clinical judgement. Within the analysis sample of n = 503 patients, 29.0% (n = 146) had a formal DAS28 score reported by the completing physician at that consultation or within 4 weeks prior. As data based on the physicians’ own clinical judgment were included, clinical outcomes were stratified by categories of physician-reported DAS28 scores (remission, LDA, MDA, HDA) at the most recent follow-up to assess if disease activity corresponded with severity of RA, physician-reported level of pain and various symptoms experienced (e.g., tender joints, swollen joints, stiffness in joints, loss of movement, sleep disturbance) (Supplemental Table S1). In addition, to ensure that physician clinical judgement aligned closely and was reflective of objective DAS28 assessment in clinical practice, Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to assess the correlation between physician-reported DAS28 and objective DAS28 scores. The results of this analysis indicated a strong correlation (Supplemental Table S2).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive summary statistics, including mean and standard deviation, were calculated for continuous variables. Frequency counts and percentages were calculated for categorical variables. For any missing values, patients were removed from all analyses in which that variable was used. There was no imputation of missing data. The number of patients with available data for each variable can be found in Table 1. Analyses were performed using UNICOM Intelligence Reporter, version 7.5.1 (UNICOM Systems, Inc. 2021. UNICOM Intelligence, Version 7.5.1. Mission Hills, CA: UNICOM Systems, Inc.) and Stata 17 (StataCorp, 2021. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC).

The frequency and percentage of patients who achieved a change in physician-reported disease activity based on DAS28 (remission, < 2.6; LDA, 2.6 to < 3.2; MDA, ≥ 3.2–5.1; and HDA, > 5.1) from initiation of AT after TNFi to the follow-up visit for each treatment group were calculated.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics were balanced using inverse-probability-weighted regression adjustment (IPWRA). IPWRA estimators use weighted regression coefficients to compute the averages of the outcome, which are converted to percentages (×100) for binary outcomes. The covariates balanced within the IPWRA were patient age, biological sex, CCI score, patients’ DAS28 at initiation of their current treatment as reported by their physician for the weighting and regression adjustment stage, and additionally current AT duration was used for the regression adjustment stage. Only patients who had data available for all variables were included in the IPWRA. Of the study population of 503, 493 (98%) were included in the adjusted analysis utilizing IPWRA; 10 patients were excluded because of missing data for DAS28 and pain at initiation of current advanced therapy treatment. Standard mean differences (SMDs) were reported for covariates before and after weighting.

Outcomes were modeled using IPWRA and reported as predicted percentages along with p values for each treatment group. IPWRA was conducted separately and compared between TNFi-UPA versus TNFi-TNFi and TNFi-UPA versus TNFi-other MOA.

Ethics

Using a check box, patients provided informed consent for use of their anonymized and aggregated data for research and publication in scientific journals. Data were collected in such a way that patients and physicians could not be identified directly; all data were aggregated and de-identified before receipt. Data collection was undertaken in line with European Pharmaceutical Marketing Research Association guidelines, and therefore it does not require ethics committee approval. The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments.

Results

Clinical Characteristics at Initiation of Current Treatment

Of 503 patients who switched from their initial TNFi, 261 switched to UPA (TNFi-UPA), 128 to another TNFi (TNFi-TNFi), and 114 to a treatment with a different MOA (TNFi-other MOA). At initiation of treatment switch to each class of therapy, more than half the patients had MDA/HDA (TNFi-UPA: 73%; TNFi-TNFi: 52%; TNFi-other MOA: 60%) and at least one-third had received adalimumab as a first-line treatment (TNFi-UPA: 58%; TNFi-TNFi: 33%; TNFi-other MOA: 46%) (Table 1). Patients switched treatment for a number of reasons (see Table 1), the most common being loss of response over time (TNFi-UPA: 50%; TNFi-TNFi: 41%; TNFi-other MOA: 45%), followed by worsening of their condition (TNFi-UPA: 43%; TNFi-TNFi: 33%; TNFi-other MOA: 47%) and lack of alleviation of pain (TNFi-UPA: 28%; TNFi-TNFi: 15%; TNFi-other MOA: 9%).

Unadjusted Physician-Reported Outcomes: Change in Disease Activity from Initiation of Current Treatment to Most Recent Follow-up at ≥ 6 Months

At the point of switch, 11.1% (n = 29) of TNFi-UPA patients (n = 261) were in remission, followed by 16.1% (n = 42) in LDA, 51.3% (n = 134) in MDA, and 21.5% (n = 56) in HDA (Fig. 1). In TNFi-TNFi patients (n = 121), 18.2% (n = 22) were in remission, 29.8% (n = 36) in LDA, 44.6% (n = 54) in MDA, and 7.4% (n = 9) in HDA (Fig. 2). In TNFi-other MOA patients (n = 111), 15.3% (n = 17), 24.3% (n = 27), 45.9% (n = 51), and 14.4% (n = 16) were in remission, LDA, MDA, or HDA, respectively (Fig. 3).

At follow-up, 51.0% (n = 133) of TNFi-UPA patients (n = 261) were in remission, followed by 29.5% (n = 77) in LDA, 18.0% (n = 47) in MDA, and 1.5% (n = 4) in HDA (Fig. 1). In all TNFi-TNFi patients (n = 121), 44.6% (n = 54) were in remission, 35.5% (n = 43) in LDA, 19.0% (n = 23) in MDA, and 0.8% (n = 1) in HDA (Fig. 2). In all TNFi-other MOA patients (n = 111), 45.0% (n = 50), 44.1% (n = 49), 10.8% (n = 12), and 0.0% were in remission, LDA, MDA, or HDA, respectively (Fig. 3).

In the TNFi-UPA, TNFi-TNFi, and TNFi-other MOA groups, 45.5%, 35.2%, and 43.1% of patients, respectively, improved from being in MDA at initiation to remission at follow-up. Additionally, in the TNFi-UPA, TNFi-TNFi, and TNFi-other MOA groups, 44.6%, 33.3%, and 25.0% of patients improved from being in HDA at initiation to remission at follow-up, respectively.

In the TNFi-UPA, TNFi-TNFi, and TNFi-other MOA groups, 25.4%, 37.0%, and 49.0% of patients improved from being in MDA at initiation to LDA at follow-up, respectively. In the TNFi-UPA, TNFi-TNFi, and TNFi-other MOA groups, 37.5%, 44.4%, and 50.0% of patients improved from being in HDA at initiation to LDA at follow-up, respectively.

Adjusted Physician-Reported Outcomes

Before weighting, the percentage of male patients in the TNFi-UPA versus TNFi-TNFi groups was 39.5% vs. 28.1% (SMD − 24.1%) and the mean age was 54.3 and 55.2 years (SMD 8.1%), respectively. The percentage of patients in remission/LDA was 27.2% vs. 47.9% (SMD 43.7%), respectively (Table 2). The mean CCIs for TNFi-UPA and TNFi-TNFi patients were 1.2 and 1.3 (SMD 8.9%), respectively. After weighting, the percentage of male patients in the TNFi-UPA versus TNFi-TNFi groups was 35.6% vs. 34.2% (SMD − 3.1%) and the mean age was 54.5 and 54.3 years (SMD − 1.4%), respectively. The percentage of patients in remission/LDA was 33.7% vs. 33.9% (SMD 0.4%), respectively. The mean CCIs for TNFi-UPA and TNFi-TNFi patients were 1.2 and 1.2 (SMD 1.0%), respectively. Similar before and after weighting results were observed for the TNFi-UPA versus TNFi-other MOA groups (Table 3).

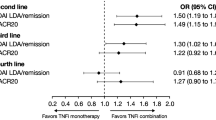

After adjustment for differences in characteristics at the time of switch, IPWRA showed that patients who switched from TNFi to UPA were significantly more likely to have achieved physician-reported remission (67.7% vs. 40.3%; p = 0.002), no pain (55.7% vs. 25.4%; p = 0.001), and complete adherence (60.0% vs. 34.2%; p = 0.005) compared with patients who had switched from TNFi to another TNFi (Fig. 4). Physicians reported no fatigue in 45.4% of patients switching from TNFi to UPA compared with 28.4% of patients switching to another TNFi (p = 0.055) (Fig. 4).

Similarly, patients switching from TNFi to UPA were significantly more likely to have achieved physician-reported remission (69.0% vs. 44.0%; p = 0.008), no pain (57.7% vs. 20.9%; p < 0.001), and complete adherence (61.1% vs. 32.7%, p = 0.003) versus patients switching from TNFi to another MOA (Fig. 5). Physicians reported that no fatigue was observed in 43.4% of TNFi-UPA patients compared with 26.7% of patients in the TNFi-other MOA group (p = 0.075) (Fig. 5).

Adjusted physician-reported outcomes: TNFi-UPA versus TNFi-other MOA. Other MOA includes patients receiving either an IL-6 inhibitor, CD20 inhibitor, or CTLA-4 co-stimulator. CD20 B lymphocyte antigen CD20, CTLA-4 cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, IL interleukin, MOA mechanism of action, TNFi tumor necrosis factor inhibitor, UPA upadacitinib

The frequencies for outcomes in RA by categories of physician-reported DAS28 scores are shown in Supplemental Table S1. The results show a high degree of congruency between physician-reported disease activity and variables of interest, wherein patients in physician-reported remission had better outcomes than patients who had physician-reported HDA.

Discussion

The findings of this study demonstrated that for patients who switched from a TNFi to UPA, physicians were significantly more likely to report that their patients were in remission, had no pain, and were completely adherent to treatment, compared with patients who cycled from one TNFi to another TNFi or switched from a TNFi to an AT with a different MOA. Although the difference was not statistically significant, physicians were also more likely to report no fatigue for patients who switched from a TNFi to UPA compared with those who cycled to another TNFi or switched from a TNFi to an AT with another MOA.

In this study, better physician-reported outcomes were observed for patients who switched from TNFi to UPA compared with those who switched to another TNFi or from TNFi to an AT with another MOA. Results of other real-world studies support these findings; in the FIRST registry study (a multi-institutional cohort of patients with RA who were treated with b/tsDMARDs in Japan), patients who had an inadequate response to their first TNFi and switched to a JAKi had better outcomes on the Clinical Disease Activity Index and Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index than patients who cycled TNFis [30]. Additionally, in the KOrean nationwide BIOlogics and targeted therapy (KOBIO) registry study, treatment discontinuation was lower in patients who switched to a JAKi after failing their first TNFi compared with patients cycling to a second TNFi [31].

Furthermore, in the Rotation or Change (ROC) trial, a greater percentage of patients who switched from a TNFi to a biologic with another MOA versus cycling TNFis achieved DAS28-ESR LDA (41% vs. 23%, respectively) and remission (27% vs. 14%, respectively) at week 52 [32]. These findings illustrated that switching versus cycling had better outcomes in terms of LDA and remission. However, the ROC trial did not include patients being treated with UPA as a comparison. In the current study of patients treated with UPA, an increased percentage of patients who switched from a prior TNFi achieved remission with UPA compared with cycling to another TNFi or switching to an AT with another MOA. This highlights a benefit of UPA in patients who switched from a TNFi versus cycling or switching to another MOA.

Radner et al. [7] and Alemao et al. [8] found that in patients with RA, achieving remission was associated with improved physical function, HRQoL, fatigue, and work productivity compared with patients with LDA. However, some patients are unable to achieve remission; therefore, LDA has been suggested as an alternative target for these patients [16]. Scott et al. [33] showed that although remission is associated with optimal outcomes, patients with LDA can achieve good physical functioning and improved HRQoL. Other research by Ten Klooster et al. [34] showed that patients achieving early remission at 6 months were more likely to be in remission 1, 3, and 5 years later than those not achieving early remission. Additionally, data from the Optum Clinformatics Data Mart for a cohort of patients with RA showed that the cost of patient care was greater with increasing disease activity state [10]. Kim et al. [35] demonstrated that patients in remission had less impairment of daily activities compared with patients with MDA/HDA (13% impairment vs. 42% impairment, respectively). The findings of these studies demonstrate the significant impact of RA symptoms across various aspects of a patient’s life. Therefore, it is important for patients with RA to have effective therapies available to manage RA and achieve remission or LDA to improve symptoms of pain, fatigue, and HRQoL, both in the present and potentially long-term.

The treatment landscape of RA has evolved with the introduction of many ATs in recent years [36], with a biologic agent, such as TNFi, recommended after csDMARD failure [12]. At the time of switch, most patients in this study had LDA, MDA, or HDA in all treatment groups. Around 11–18% of patients who switched treatments were in remission at the time of switch. Possible reasons for switching treatments for patients in remission may include preference for oral medication, intolerance or toxicity issues with the initial drug, wish to change frequency of dosing, or persistent pain despite remission by disease activity score. Patients not in remission may discontinue a TNFi because of loss of response over time, worsening of RA, lack of alleviation of pain, or remission not maintained or induced. When patients fail or discontinue a TNFi, the decision regarding the next therapy could be a difficult choice because recommendations do not state whether switching or cycling is the best strategy. To assess the clinical efficacy of switching versus cycling, Migliore et al. conducted a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and observational studies of patients who had failed a first-line TNFi [20]. The findings demonstrated that switching from TNFi to a drug with another MOA versus TNFi cycling was more effective. However, this study has its limitations in that comparability could not be ensured between cohorts of patients across studies and not all drugs, for example UPA, were included in the analysis [20]. Therefore, additional studies on switching versus cycling in TNFi-experienced patients are needed to help guide clinicians and patients, in considering second- or third-line therapies that are most effective in the management of RA. The current study adds value to the published literature by showing the benefit of switching from a first-line TNFi to UPA versus cycling to another TNFi or switching to another MOA in patients with RA.

The current study is novel in that UPA is included in the analysis. A strength of this analysis is that it assesses real-world data and includes a large, representative sample of consulting patients that clinical trials usually exclude. It is also worth noting that even though there were differences in the CV risk factors across treatment groups, they were balanced and adjusted within the IPWRA analyses by inclusion on CCI index. The CCI is calculated using a number of comorbidities which include myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, as well as the patient’s age. Therefore, any results and outcomes of our analysis have taken into account the CV risk across all cohorts. Limitations of this study include that some of the effectiveness results rely on physicians’ own clinical judgment rather than quantifiable disease measures, which may limit the study’s findings. The DAS28 is not routinely collected in every consultation with patients with RA in a real-world clinical setting. Therefore, in a real-world study, obtaining objective DAS28 assessments for all patients is unlikely. As a result of this limitation, physicians were instead asked, in addition to objective DAS28 assessments, for an estimated DAS28 score based on the categories of remission, < 2.6; LDA, 2.6 to < 3.2; MDA, ≥ 3.2–5.1; and HDA, > 5.1. In this analysis of patients from the DSP, 29% had a DAS28 assessment at their consultation or within 4 weeks prior, the remaining 71% of patients had an estimated DAS28 score based on physicians’ clinical judgement. As this DAS28 assessment is only partially objective, other clinical outcomes were stratified by the DAS28 categories to illustrate that there was a high degree of congruency between physician-reported DAS28 and other disease parameters (Supplemental Table S2). Furthermore, patients from the DSP sample do not constitute a true random sample, more so a pragmatic (physicians) and pseudo-random (patients) sample. Also, although minimal selection criteria were imposed to identify physicians for inclusion, participation is influenced by the willingness to complete the record forms. In addition, some patients from the study population were excluded from adjusted analyses because of missing data for some variables; however, this represented a very small minority of patients (n = 10), and therefore we expect the impact of missing data bias was low. The patient sample may be more severely affected by their disease and/or treatment due to their consulting nature (i.e., a requirement for inclusion in the DSP). Furthermore, patients who consult more frequently are more likely to be included in the patient sample. However, physicians were asked to provide data for a number of consecutively consulting patients meeting the DSP inclusion criteria to reduce selection bias. No patient selection verification procedures were applied to the DSP, and identification of the participants included was based on physician judgment/perception rather than formal medical coding (e.g., diagnostic codes). Nevertheless, this process is representative of physicians’ real-world classification of their patients. Additionally, these patients not only were on their respective AT but some patients were also treated in combination with a csDMARD and/or a corticosteroid and other common RA treatment; therefore, these treatments are not being compared in isolation.

Conclusions

The findings of this real-world study of patients with RA demonstrate that switching from TNFi to UPA versus TNFi to another TNFi or to an AT with another MOA was associated with greater proportions of patients achieving remission, having no pain, and achieving complete medication adherence, as reported by physicians. Therefore, the results illustrate that UPA can improve disease management and alleviate disease-related symptoms in patients with RA.

Data Availability

All data, i.e., methodology, materials, data, and data analysis, that support the findings of this survey are the intellectual property of Adelphi Real World. All requests for access should be addressed directly to Oliver Howell at oliver.howell@adelphigroup.com. Oliver Howell is an employee of Adelphi Real World.

References

Smolen JS, Aletaha D, McInnes IB. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2016;388(10055):2023–38.

Chauhan K, Jandu JS, Brent LH, Al-Dhahir MA. Rheumatoid arthritis. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls; 2023.

Mehta B, Pedro S, Ozen G, et al. Serious infection risk in rheumatoid arthritis compared with non-inflammatory rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases: a US national cohort study. RMD Open. 2019;5(1):e000935.

Solomon D, Reed G, Kremer J, et al. Disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of cardiovascular events. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(6):1449–55.

Kekow J, Moots R, Khandker R, Melin J, Freundlich B, Singh A. Improvements in patient-reported outcomes, symptoms of depression and anxiety, and their association with clinical remission among patients with moderate-to-severe active early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2011;50(2):401–9.

Emery P, Burmester GR, Bykerk VP, et al. Evaluating drug-free remission with abatacept in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from the phase 3b, multicentre, randomised, active-controlled AVERT study of 24 months, with a 12-month, double-blind treatment period. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(1):19–26.

Radner H, Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Remission in rheumatoid arthritis: benefit over low disease activity in patient-reported outcomes and costs. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16(1):1–10.

Alemao E, Joo S, Kawabata H, et al. Effects of achieving target measures in rheumatoid arthritis on functional status, quality of life, and resource utilization: analysis of clinical practice data. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(3):308–17.

Ostor AJ, Sawant R, Qi CZ, Wu A, Nagy O, Betts KA. Value of remission in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a targeted review. Adv Ther. 2022;39:1–19.

Curtis JR, Fox KM, Xie F, et al. The economic benefit of remission for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Ther. 2022;9(5):1329–45.

Gauthier G, Levin R, Vekeman F, Reyes JM, Chiarello E, Ponce de Leon D. Treatment patterns and sequencing in patients with rheumatic diseases: a retrospective claims data analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(12):2185–96.

Smolen JS, Landewé RB, Bergstra SA, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2022 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(1):3–18.

Strand V, Miller P, Williams SA, Saunders K, Grant S, Kremer J. Discontinuation of biologic therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: analysis from the Corrona RA Registry. Rheumatol Ther. 2017;4:489–502.

Rubbert-Roth A, Szabó MZ, Kedves M, Nagy G, Atzeni F, Sarzi-Puttini P. Failure of anti-TNF treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the pros and cons of the early use of alternative biological agents. Autoimmun Rev. 2019;18(12): 102398.

Souto A, Maneiro JR, Gomez-Reino JJ. Rate of discontinuation and drug survival of biologic therapies in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of drug registries and health care databases. Rheumatology. 2016;55(3):523–34.

Fraenkel L, Bathon JM, England BR, et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(7):1108–23.

Taylor PC, Matucci Cerinic M, Alten R, Avouac J, Westhovens R. Managing inadequate response to initial anti-TNF therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: optimising treatment outcomes. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/1759720X221114101.

Johnson KJ, Sanchez HN, Schoenbrunner N. Defining response to TNF-inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis: the negative impact of anti-TNF cycling and the need for a personalized medicine approach to identify primary non-responders. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38(11):2967–76.

Karpes Matusevich AR, Suarez-Almazor ME, Cantor SB, Lal LS, Swint JM, Lopez-Olivo MA. Systematic review of economic evaluations of cycling versus swapping medications in patients with rheumatoid arthritis after failure to respond to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72(3):343–52.

Migliore A, Pompilio G, Integlia D, Zhuo J, Alemao E. Cycling of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors versus switching to different mechanism of action therapy in rheumatoid arthritis patients with inadequate response to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors: a Bayesian network meta-analysis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/1759720X211002682.

AbbVie. AbbVie receives FDA approval of RINVOQ™ (upadacitinib), an oral jak inhibitor for the treatment of moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis [press release]. 2019. https://news.abbvie.com/alert-topics/immunology/abbvie-receives-fda-approval-rinvoq-upadacitinib-an-oral-jak-inhibitor-for-treatment-moderate-to-severe-rheumatoid-arthritis.html. Accessed Aug 16, 2023.

European Medicines Agency. Rinvoq. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/rinvoq. Accessed Feb 13, 2023.

Koike T, Inui K. How can the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis be improved in Japan? Int J Clin Rheumtol. 2015;10(4):235–45.

Anderson P, Benford M, Harris N, Karavali M, Piercy J. Real-world physician and patient behaviour across countries: disease-specific programmes—a means to understand. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(11):3063–72.

Anderson P, Higgins V, Courcy JD, et al. Real-world evidence generation from patients, their caregivers and physicians supporting clinical, regulatory and guideline decisions: an update on Disease Specific Programmes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2023;39(12):1707–15.

Babineaux S, Curtis B, Holbrook T, Milligan G, Piercy J. Evidence for validity of a national physician and patient-reported, cross-sectional survey in China and UK: the disease specific programme. BMJ Open. 2016;6(8):e010352.

Higgins V, Piercy J, Roughley A, et al. Trends in medication use in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a long-term view of real-world treatment between 2000 and 2015. Diabet Metab Syndr Obes Targets Ther. 2016;9:371–80.

Yamaoka K, Tanaka Y, Kameda H, et al. The safety profile of upadacitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Japan. Drug Saf. 2021;44:711–22.

AbbVie. AbbVie receives health Canada approval of RINVOQ® (upadacitinib), an oral medication for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe active rheumatoid arthritis [press release]. https://www.abbvie.ca/content/dam/abbvie-dotcom/ca/en/documents/press-releases/Rinvoq-press-release-EN_FINAL.pdf. Accessed Feb 13, 2023.

Ochi S, Sonomoto K, Nakayamada S, Tanaka Y. Preferable outcome of Janus kinase inhibitors for a group of difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis patients: from the FIRST Registry. Arthritis Res Ther. 2022;24(1):1–13.

Park D-J, Choi S-E, Kang J-H, Shin K, Sung Y-K, Lee S-S. Comparison of the efficacy and risk of discontinuation between non-TNF-targeted treatment and a second TNF inhibitor in patients with rheumatoid arthritis after first TNF inhibitor failure. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/1759720X221091450.

Gottenberg J-E, Brocq O, Perdriger A, et al. Non-TNF-targeted biologic vs a second anti-TNF drug to treat rheumatoid arthritis in patients with insufficient response to a first anti-TNF drug: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(11):1172–80.

Scott I, Ibrahim F, Panayi G, et al. The frequency of remission and low disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and their ability to identify people with low disability and normal quality of life. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;49(1):20–6.

Ten Klooster PM, Oude Voshaar MA, Fakhouri W, de la Torre I, Nicolay C, van de Laar MA. Long-term clinical, functional, and cost outcomes for early rheumatoid arthritis patients who did or did not achieve early remission in a real-world treat-to-target strategy. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:2727–36.

Kim D, Kaneko Y, Takeuchi T. Importance of obtaining remission for work productivity and activity of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2017;44(8):1112–7.

Findeisen KE, Sewell J, Ostor AJ. Biological therapies for rheumatoid arthritis: an overview for the clinician. Biol Targets Ther. 2021;15:343–52.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Medical writing services were provided by Natalie Mitchell of Fishawack Facilitate Ltd., part of Avalere Health, and funded by AbbVie.

Funding

Data collection was undertaken by Adelphi Real World as part of an independent survey, entitled the Adelphi Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Specific Programme (DSP). The DSP is a wholly owned Adelphi product and is the intellectual property of Adelphi Real World. The analysis described here used data from the Adelphi Rheumatoid Arthritis DSP. AbbVie was one of multiple subscribers to the DSP and did not influence the original survey through either contribution to the design of questionnaires or data collection. All authors had access to the data results and participated in the development, review, and approval of this manuscript. AbbVie funded this publication and the Rapid Service Fee. No honoraria or payments were made for authorship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Roberto Caporali, Aditi Kadakia, Oliver Howell, Jayesh Patel, Jack Milligan, Sander Strengholt, Sophie Barlow, and Peter C. Taylor contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Oliver Howell, Jack Milligan, and Sophie Barlow. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Roberto Caporali has received speaker and/or consultant fees from AbbVie, Accord, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Fresenius, Galapagos, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer Inc, and UCB. Peter C. Taylor has received grant and/or research support from Galapagos and has acted as a consultant for AbbVie, Biogen, Eli Lilly, Fresenius, Galapagos, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Nordic Pharma, Pfizer Inc, Sanofi, and UCB. Jayesh Patel, Aditi Kadakia, and Sander Strengholt are employees of AbbVie Inc and may own stock. Oliver Howell, Jack Milligan, and Sophie Barlow are employees of Adelphi Real World, who acted as consultants to AbbVie for this analysis and have no other conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

Using a check box, patients provided informed consent for use of their anonymized and aggregated data for research and publication in scientific journals. Data were collected in such a way that patients and physicians could not be identified directly; all data were aggregated and de-identified before receipt. Data collection was undertaken in line with European Pharmaceutical Marketing Research Association guidelines, and therefore it does not require ethics committee approval. The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Caporali, R., Kadakia, A., Howell, O. et al. A Real-World Comparison of Clinical Effectiveness in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis Treated with Upadacitinib, Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors, and Other Advanced Therapies After Switching from an Initial Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitor. Adv Ther (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-024-02948-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-024-02948-0