Abstract

Introduction

Clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of all-oral direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimens in the treatment of patients infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV). This study assessed real-world effectiveness of two recently approved regimens; paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir; dasabuvir (3D), and sofosbuvir/ledipasvir (SOF/LDV) in patients with HCV genotype 1.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of administrative claims data (IMS Health Patient-Centric Data Warehouse/Medivo database) from October 1, 2013 to August 14, 2015 was conducted. Patients ≥19 years of age with a HCV genotype 1 infection, a prescription fill for 3D or SOF/LDV, and ≥1 HCV viral load (VL) assessment from weeks 4–30 post-treatment were selected for analysis. Percentages of patients achieving sustained virologic response (SVR; defined as HCV RNA ≤43 IU/mL) were determined. Unadjusted SVR rates were compared between treatment groups using Fisher’s exact tests. SVR rates were also assessed using multivariate regression with adjustment for age group, sex, and treatment history. Analyses were repeated for a subset of patients with VL assessment from 12 to 30 weeks post-treatment.

Results

A total of 1707 (44 3D and 1663 SOF/LDV) patients were included. The majority (60%) were male, 49% were aged 55–64 years, and 97% were treatment-naïve 1 year prior to index. The unadjusted relative risk (RR) for achieving SVR in patients treated with SOF/LDV compared with 3D was 0.98%, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.93–1.02. After adjusting for the baseline covariates, the RR was 0.98%, 95% CI: 0.94–1.03.

Conclusions

In this early view of real-world data, effectiveness of all-oral DAA regimens in HCV genotype 1 patients was concordant with results from registration trials. SVR rates were similar for the two regimens. Further studies are needed to confirm these results.

Funding

AbbVie, Inc.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chronic hepatitis C (CHC) is a progressive liver disease caused by infection with the hepatitis C virus (HCV). CHC affects approximately 130–150 million people globally, and up to 500,000 people die each year from liver diseases associated with CHC [1]. In the United States (US), approximately 3 million individuals are infected with HCV. Approximately, 75% of these infections are attributed to HCV genotype 1 [2]. The first-generation direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) include the NS3/4A serine protease inhibitors telaprevir and boceprevir, and the NS5B ribonucleic acid (RNA) polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir. Clinical trials demonstrated that use of these DAAs in combination with peginterferon and ribavirin was associated with sustained virologic response (SVR) in up to 75% (telaprevir and boceprevir) to 90% (sofosbuvir) of patients with HCV genotype 1 infection [3]. However, results of real-world studies of these regimens have been discordant with those of the clinical trials. For example, SVR rates in real-world studies of telaprevir have been reported at 44–52%, and at 72% for older sofosbuvir-based regimens [4–6].

The second-generation DAA regimens paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir; dasabuvir (3D) and sofosbuvir/ledipasvir (SOF/LDV) were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for patients with HCV genotype 1. These all-oral regimens have been associated with improved efficacy, safety, tolerability, and shorter durations when compared to first-generation protease inhibitor regimens [3, 7]. Additionally, these newer regimens have been shown to be cost-effective across all fibrosis stages [8, 9]. Clinicians and payers have anticipated the demonstration of real-world effectiveness of these new DAA regimens. However, reports available to date are limited to data describing the effectiveness of individual therapies, and are only in abstract form. Most recently, real-world data from Poland demonstrated 98% SVR12 with 3D [10]. This report presents the first analysis of the US real-world effectiveness of these new HCV treatment regimens as measured by SVR rates captured from a large pharmacy and laboratory claims database.

Methods

An analysis of the IMS Health Patient-Centric Data Warehouse/Medivo database from October 1, 2013 to August 14, 2015 was conducted to compare real-world SVR rates among patients treated with 3D and SOF/LDV. Data were obtained from the IMS Health Patient-Centric Data Warehouse (Alexandria, VA, USA), with approximately 240 million patients in the pharmacy database, integrated with medical and laboratory claims (Medivo laboratory data). The IMS database contains de-identified, longitudinal, patient-level records, including clinical and demographic information (e.g., age, sex, and comorbidities), inpatient and outpatient medical claims (e.g., admission and discharge dates and procedure and diagnosis codes, laboratory tests), and pharmacy claims data (e.g., drug dispensed based on national drug codes, quantity and date dispensed, drug strength, and days’ supply).

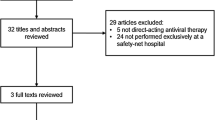

This was a real-world study; the observation period was selected based on the FDA approval dates of the new DAAs (October 2014 and December 2014 for SOF/LDV and 3D, respectively) plus 1 year previous to assess baseline characteristics (age, sex, treatment history, and comorbidities). Patients were eligible if they received ≥1 prescription fill of 3D (with or without ribavirin) or SOF/LDV from October 1, 2014, through August 14, 2015, were ≥19 years of age, had a diagnosis of CHC (with an HCV genotype test confirming genotype 1), and had ≥1 HCV RNA test from week 4 to week 30 post-treatment to determine viral eradication. Patients were excluded if they had a prescription filled for both DAAs, had a non-genotype-1 (or unknown genotype) infection, or had no record of an HCV RNA test during the week 4 to week 30 post-treatment period. The index date was defined as the first DAA regimen prescription fill date (Fig. 1). End of treatment (EOT) was defined as the last DAA fill date plus number of days supplied. SVR was categorized qualitatively as detectable or undetectable or quantitatively based on HCV RNA result of ≤43 IU/mL (undetectable) and >43 IU/mL (detectable). For this report, SVR rates were collected from post-treatment weeks 4–30. If >1 HCV RNA lab assessment was available, the result closest to 30 weeks post-treatment was used. Time to post-treatment HCV RNA determination is the physician’s decision, and may not be related to HCV treatment.

Study design. The index date was defined as the date of the first prescription fill for 3D or SOF/LDV. Baseline characteristics were assessed in the year prior to the index date. The primary analysis included patients with a viral load assessment from 4 to 30 weeks following EOT. An ad hoc analysis was limited to patients with a viral load assessment from 12 to 30 weeks following EOT. 3D Paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir; dasabuvir, DAA direct-acting antiviral, EOT End of treatment, SOF/LDV Sofosbuvir/ledipasvir, VL Viral load, wks weeks

Baseline sociodemographic characteristics, 1-year prior treatment history, and comorbidities were summarized using descriptive statistics; Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to assess differences between treatment groups. The distribution of HCV RNA testing over time among patients in the sample was also assessed descriptively, using medians and interquartile range to describe the distributions. Two patient groups were defined; those with ≥1 viral load assessment during the 4- to 30-week follow-up period (primary analysis of SVR rates), and a subgroup with an assessment from 12 to 30 weeks (ad hoc analysis) representing SVR12, the commonly accepted reference for cure American Association for the Study of Liver Disease/Infectious Diseases Society of America (AASLD/IDSA) [11]. SVR rates were examined using descriptive statistics, and differences in SVR rates between treatment groups were assessed using Fisher’s exact tests. SVR rates were also assessed using multivariate logistic regression analysis, controlling for age group, sex, and treatment history. Results were summarized using parameter estimates (β) and standard errors. A priori, P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed with the use of SAS 9.3 for Windows XP (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA).

This study was based on administrative claims data, and does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Results

A total of 55,871 patients in the database received a prescription for 3D (n = 2174) and/or SOF/LDV (n = 53,697) during the study period (Fig. 2). Of these, 169 were excluded because of a prescription for both DAAs, and 13 (3D) and 592 (SOF/LDV) were exclude for age <19 years of age. Of the remaining 54,928 patients, 18.5% (n = 369, 3D) and 18.2% (n = 9643, SOF/LDV) had a genotype test available in the database, of which 98.6% (n = 364, 3D) and 98.1% (n = 9461, SOF/LDV) were genotype 1. Of these, 181 (3D) and 5755 (SOF/LDV) patients in the 4–30 weeks cohort finished HCV treatment and were eligible for determining EOT; 161 (3D) and 5230 (SOF/LDV) had ≥4 weeks of follow-up from EOT; and 44 (3D) and 1663 (SOF/LDV) had at least one viral load between weeks 4 and 30 post-treatment. For the 12–30 weeks cohort, 71 (3D) and 3279 (SOF/LDV) had ≥12 weeks of follow-up from EOT and 15 (3D) and 862 (SOF/LDV) had at least one viral load between weeks 12 and 30 post-treatment.

Baseline characteristics of the patients in each treatment group were similar (Table 1). The majority (60%) of patients were male, and nearly half (49%) were aged 55–64 years. In addition, the majority (97%) of patients have not received HCV treatment in the year prior to the index date. Not all patients in the IMS database could be linked with the Medivo Laboratory database; therefore, only 36% (n = 611) of these patients had comorbidities listed. Comorbidities were based on International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes and were assessed 1 year prior to treatment. Gastrointestinal disorders and diabetes were the most common comorbidities in 3D and diabetes and cirrhosis were the most common comorbidities in SOF/LDV. Among patients with comorbidities listed, no patients in the sample had received a liver transplant. No significant differences in comorbidities were found between treatment groups.

The distribution of HCV RNA tests over the follow-up period is illustrated in Fig. 3. The median time of SVR assessment was approximately 12 weeks (85 days) following the EOT for patients who received SOF/LDV, and approximately 9 weeks (61 days) for those who received 3D. HCV RNA test distributions were 42 vs. 49 days (1st quartiles) and 95 vs. 108 days (3rd quartiles), for 3D and SOF/LDV, respectively (Fig. 3A). Among 877 patients with a viral load assessment from 12 to 30 weeks following the EOT (n = 15 for 3D; n = 862 for SOF/LDV), the median time of assessment was approximately 15 weeks for patients in both groups (Fig. 3b).

As illustrated in Fig. 4, the majority of patients with a viral load assessment achieved SVR in each treatment group. When including latest viral load assessed within 4–30 weeks post-treatment, unadjusted SVR rates were 98% and 96% for patients who received 3D and SOF/LDV, respectively (Fig. 4). An ad hoc analysis of patients with a viral load assessment from 12 to 30 weeks post-treatment showed unadjusted SVR rates of 100% and 95% for 3D and SOF/LDV, respectively. The differences in SVR rates between treatment groups were not statistically significant (P = 1.0). Results of multivariate analyses controlling for age group, sex, and treatment history confirmed that SVR rates (parameter estimate −0.017, P = 0.5032) were not statistically significant for patients assessed from 4 to 30 weeks post-treatment (Table 2). However, ad hoc analysis of SVR from 12 to 30 weeks demonstrated that patients treated with SOF/LDV were 8.4% less likely to achieve SVR than those treated with 3D (parameter estimate −0.084, P < 0.0001). The unadjusted relative risk (RR) for achieving SVR in patients treated with SOF/LDV compared with 3D was 0.98%, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.93–1.02. After adjusting for the baseline covariates, the RR was 0.98%, 95% CI: 0.94–1.03 (Table 3).

Discussion

Results from controlled clinical trials have suggested that the emergence of novel, all-oral DAA regimens holds the promise of achieving much higher rates of SVR among patients infected with HCV than was possible with previous treatments, with improved efficacy and tolerability, and reduced treatment duration [12–19]. This is the first report of the effectiveness as measured by post-treatment SVR rates associated with both 3D and SOF/LDV in a real-world setting.

This early view of effectiveness was concordant with overall SVR12 >95% demonstrated in clinical trials involving both of these treatments ([12, 13]; Abbvie, data on file). SVR12 is currently the most common endpoint used in clinical trials of novel HCV treatments, and was the assessment used in the pivotal trials involving both 3D and SOF/LDV. However, we found that in this real-world analysis of claims data, the timing of HCV RNA assessments seems to vary. In addition, SVR24 was previously used as the primary endpoint for registration studies; however, regulatory agencies now accept an earlier post-treatment virologic assessment, SVR12, for approval of new regimens [20]. To capture all available post-treatment SVR, the observation period was extended to 30 weeks. Available data suggest that a virologic assessment at 4 weeks predicts SVR12, since studies have demonstrated a high degree of concordance among SVR4, SVR12, and SVR24. A study by Chen et al. [20] established positive predictive values of 99% and 94% for prediction of SVR24 from SVR12 and SVR4, respectively, among subjects with HCV genotype 1 infection treated with DAAs. In addition, identical rates of SVR4 and SVR12 were reported in a recent study of patients with HCV genotype-1/HIV-1 coinfection treated with concomitant 3D and HIV-1 antiretroviral treatment [21]. Therefore, for this study, the earliest time for assessment of SVR was 4 weeks following the EOT. To accommodate real-world variability in the timing of SVR assessment, this study included SVR rates ranging from 4 weeks to 30 weeks post-treatment. When multiple viral load results were available, the result closest to 30 weeks was used to reflect the real-world SVR of the new DAAs. However, since the AASLD/IDSA 2015 guidelines [11] recommend the SVR rate to be collected at 12 or more weeks after completing treatment, we also reported 12- to 30-week SVR rates. Due to the early view of this data, limiting the SVR to 12–30 weeks resulted in a small sample size; caution should be used in interpreting this result. These results were shown to be in concordance with the 4- to 30-week results.

In the 4- to 30-week cohort, the median time of viral load testing was approximately 3 weeks earlier for patients on 3D vs. those on SOF/LDV. In contrast, the median time of testing in the 12- to 30-week cohort was similar (<1 week difference) for patients on both regimens. The differences in these times may be a reflection of the FDA approval dates and HCV treatment start dates: The later in the observation period a patient begins HCV treatment, the lower the probability they will be in the database long enough to have an assessment at 4 or 12 weeks post-treatment.

This study is the first to assess the real-world effectiveness of the new all-oral DAAs in the treatment of HCV. A particular strength of the study was its use of a large administrative claims database, which captured a large cross section of the US population. However, this study does have limitations that should be considered in the interpretation of these results. First, this is an early-view study; sample size was limited because the medications assessed have only been recently approved. In addition, only 27.3% (44/161) of patients had a recorded lab test during the study period, suggesting patients may have not had enough time in the study to measure an SVR. Genotype testing was limited due to the integration of the pharmacy and laboratory database, where approximately 18% of the patients in the pharmacy database were also in laboratory database. Therefore, the limited sample size precluded assessments of differences in patient subgroups of interest (e.g., HCV genotypes 1a vs. 1b, treatment-naïve vs. experienced, treatment duration, HCV/HIV-1 coinfection, fibrosis stage and presence of cirrhosis, and other comorbidities such as renal insufficiency) and may limit the ability to minimize selection bias. Additional limitations are common to studies using claims data. For example, this study was conducted using an integrated medical, pharmacy and laboratory claims database linked with laboratory data. Because the data were incompletely integrated, only 36% of the patients with pharmacy and laboratory data also had medical data for assessment of comorbidities. Similarly, because this study used a combination of databases, laboratory data were captured for only a fraction of the patients on the new DAA regimens, and laboratory tests done outside the healthcare system were not available. Because the pre-treatment assessment period was limited to 1 year prior to index date, the number of treatment-experienced patients may have been underestimated. This early analysis included only patients who had an available HCV RNA test and would have excluded patients who discontinued therapy without receiving a post-treatment HCV RNA test. Among those patients with more than one HCV RNA test post-treatment, 100% of the 3D patients HCV RNA results did not change from first to last HCV RNA results, were as only 95% of SOF/LDV HCV RNA results did not change. Finally, despite the breadth of the patient population assessed, uninsured patients were not included in the database; therefore, our results may not be fully generalizable to the full HCV population. While this is an early view of SVR rates in the real-world setting, further investigation is needed with a more comprehensive database and enough time in the study to measure an SVR.

Conclusion

This is the first report on real-world SVR rates of 3D compared with SOF/LDV in HCV genotype 1 patients. No difference in real-world SVR rates was observed between the two regimens in patients with HCV genotype 1. Further studies are needed to confirm these results.

References

World Health Association 2015. Hepatitis C fact sheet. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en/. Accessed 4 Sep 2015.

Messina JP, Humphreys I, Flaxman A, et al. Global distribution and prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology. 2015;61(1):77–87.

Feeney ER, Chung RT. Antiviral treatment of hepatitis C. BMJ. 2014;7(348):g3308.

Bichoupan K, Martel-Laferriere V, Sachs D, et al. Costs of telaprevir-based triple therapy for hepatitis C: $189,000 per sustained virological response. Hepatology. 2014;60:1187–95.

Bichoupan K, Schwartz JM, Martel-Laferriere V, et al. Effect of fibrosis on adverse events in patients with hepatitis C treated with telaprevir. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(2):209–16.

Backus LI, Belperio PS, Shahoumian TA, et al. Effectiveness of sofosbuvir-based regimens in genotype 1 and 2 hepatitis C virus infection in 4026 U.S. Veterans. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:559–73.

Pawlotsky JM. New hepatitis C therapies: the toolbox, strategies and challenges. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1176–92.

Johnson SJ, Juday TR, Samp JC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of treating different stages of genotype 1 hepatitis C virus (GT1-HCV) with viekira pak (paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir and dasabuvir) ± ribavirin compared to no treatment in the United States. Poster presentation at the 50th International Liver Congress, April 22–26 2015, Vienna, Austria.

Leidner AJ, Chesson HW, Xu F, et al. Cost-effectiveness of hepatitis C treatment for patients in early stages of liver disease. Hepatology. 2015;61(6):1860–9.

Flisiak, R. et al, Efficacy and safety of Paritaprevir/r/Ombitasvir/Dasabuvir ± Ribavirin in GT1 HCV infected patients treated in real life settings, presented Viral Hepatitis Congress, Frankfurt, September, 10–12 2015.

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases/Infectious. Diseases Society of America (AASLD/IDSA) HCV guidance panel. Hepatitis C guidance: AASLD-IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating adults infected with hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2015;62:932–54.

Afdhal N, Reddy KR, Nelson DR, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for previously treated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1483–93.

Afdhal N, Zeuzem S, Kwo P, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for untreated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1889–98.

Kowdley KV, Gordon SC, Reddy KR, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for 8 or 12 weeks for chronic HCV without cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1879–88.

Naggie S, Cooper C, Saag M, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for HCV in patients coinfected with HIV-1. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:705–13.

Feld JJ, Kowdley KV, Coakley E, et al. Treatment of HCV with ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1594–603.

Zeuzem S, Jacobson IM, Baykai T, et al. Retreatment of HCV with ABT-450/r–ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1604–14.

Sulkowski MS, Eron JJ, Wyles D, et al. Ombitasvir, paritaprevir co-dosed with ritonavir, dasabuvir, and ribavirin for hepatitis C in patients co-infected with HIV-1: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2015;313:1223–31.

Poordad F, Hezode C, Trinh R, et al. ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin for hepatitis C with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1973–82.

Chen J, Florian J, Carter W, et al. Earlier sustained virologic response end points for regulatory approval and dose selection of hepatitis C therapies. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(7):1450–5.

Eron JJ, Lalezari J, Slim J, et al. Safety and efficacy of ombitasvir—450/r and dasabuvir and ribavirin in HCV/HIV-1 co-infected patients receiving atazanavir or raltegravir ART regimens. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(4 Suppl 3):19500.

Acknowledgments

The financial support for the study was provided by AbbVie. The article processing charges and open access fee for this publication were funded by AbbVie. All authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship, are responsible for the integrity of the work, and have given final approval to the version to be published. Medical writing assistance was provided by Eric Bertelsen, PhD, an employee of Arbor Communications, Inc. This assistance was funded by AbbVie.

Disclosures

David R. Walker is an employee of AbbVie and may own AbbVie stock. Marcos C. Pedrosa is an employee of AbbVie and may own AbbVie stock. Shivaji R. Manthena is an employee of AbbVie and may own AbbVie stock. Nikil Patel is an employee of AbbVie and may own AbbVie stock. Steven E. Marx is an employee of AbbVie and may own AbbVie stock. AbbVie participated in the interpretation of data, review, and approval of the publication.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

This study was based on administrative claims data, and does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Walker, D.R., Pedrosa, M.C., Manthena, S.R. et al. Early View of the Effectiveness of New Direct-Acting Antiviral (DAA) Regimens in Patients with Hepatitis C Virus (HCV). Adv Ther 32, 1117–1127 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-015-0258-5

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-015-0258-5