Summary

Anemia is a common finding in patients with solid or hematological malignancies. The underlying causes of cancer-related anemia can be multifactorial, including toxicity of cancer therapy, raised inflammatory conditions by the cancer, chronic bleeding and malnutrition. Therapeutic approaches for the treatment of chemotherapy induced anemia encompass red blood cell (RBC) transfusions and erythropoietin-stimulating agents (ESAs). The latter are approved for the treatment of patients with symptomatic anemia caused by palliative chemotherapy to reduce the number of RBC transfusions and gradually improve anemia-related symptoms. Before the treatment with ESA, a baseline Hb level < 10 g/dl is mandatory and iron deficiency must be ruled out. ESAs are linked to an increase in thromboembolic events and potentially raised mortality. Therefore, the risk-benefit ratio should be carefully assessed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anemia and its resulting symptoms like fatigue have a great impact on the quality of life (QoL) of patients suffering from cancer. According to the European Cancer Anemia Survey in 2004, the prevalence of anemia in patients with a solid or hematological malignancy was about 39% [1]. Elevated inflammatory cytokines from cancer cells or toxicity of cancer treatment may be reasons for impaired iron homeostasis and erythropoietic activity. Further causes like chronic bleeding (e.g., occult gastrointestinal bleeding from tumors) or malnutrition can occur simultaneously and should be ruled out during the diagnostic process or treated adequately (e.g., malnutrition). In some patients with cancer, causes of anemia remain unclear or are inevitable (e.g., myelotoxic chemotherapy). In this scenario, supportive treatment to raise hemoglobin levels and diminish symptoms from anemia, including erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs), may become necessary. This short review focuses on indications, advantages, and risks of ESAs in patients with chemotherapy-associated anemia that develops during treatment of nonhematologic malignancies.

Indication

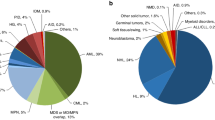

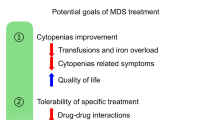

ESAs can be used in patients with symptomatic anemia (hemoglobin [Hb] < 10 g/dL) associated with myelosuppressive chemotherapy given with palliative intention to reduce the number of red blood cell (RBC) transfusions ([2, 3]; Table 1). In addition, treatment-naïve lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes with low endogenous erythropoietin (EPO) levels (< 500 IU/L) and patients with concomitant chronic kidney disease may benefit from erythropoiesis-stimulating drugs [4]. Evaluating EPO levels to screen for patients with chemotherapy-associated anemia is not recommended due to its lack of sensitivity and specificity [5].

Management

Iron deficiency in patients with cancer must be ruled out (ferritin > 100 µg/L and transferrin saturation > 20%) before treatment with ESA and supplementing ESA therapy with intravenous iron is recommended. If there is no response after 6–8 weeks (change in Hb < 1–2 g/dl or absent reduction of transfusion requirements), iron stores should be checked again. There is suggestive evidence that combining an ESA with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G‑CSF) improves chances of erythroid responses in patients presenting with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes with low erythropoietin levels and low transfusion needs [6]. Further analysis did not show any difference regarding erythroid response rates between higher doses of ESA and ESA plus G‑CSF [7, 8]. Available ESAs such as epoetin, darbepoetin, and epoetin alfa biosimilars seem to be equal in effectiveness and safety ([2, 9]; Table 2). Responses to ESA therapy takes weeks to months and therefore RBC transfusion should be used in patients where prompt relief of symptoms is necessary.

Efficacy and risks

The use of ESA in patients meeting the above-mentioned criteria lowers the number of RBC transfusions by about 35% [10] and 50–70% of patients undergoing treatment with ESA achieve an Hb increment ≥ 1 g/dL [7, 8]. ESAs may be an alternative for patients with anemia-associated symptoms, in whom RBC transfusions should be administered with caution (e.g., patients at risk of volume overload or transfusion reactions in the past). Patients who do not have easy access to transfusion (long distances to appropriate facility) or who refuse transfusion because of personal or religious beliefs (e.g., Jehovah’s Witnesses) should be considered for treatment with ESA if indicated. Whether use of ESAs can significantly improve QoL remains controversial. Although treatment with ESA in patients with chemotherapy-associated anemia improves anemia-related symptoms like dizziness, chest discomfort, and headache, the impact on fatigue-related symptoms was not clinically relevant [11,12,13,14].

During treatment with ESA, the risk of thromboembolic complications increases and it is supposedly associated with higher mortality through accelerated tumor growth [9, 15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. The use of ESAs was related to an adverse impact on survival in certain tumor entities (e.g., non-small-cell lung cancer [NSCLC], head and neck cancer receiving radiotherapy, cervical cancer receiving chemoradiotherapy, and metastatic breast cancer receiving chemotherapy), as shown by several controlled trials [19, 20, 23,24,25,26]. High target Hb levels, deaths from thromboembolism, and adverse impact on tumor progression are among the possible explanations for that observation. However, high Hb levels (before or during treatment with ESA) may be a possible explanation for the increased risk of thromboembolic events, as seen in patients with end-stage kidney disease [27]. Based on these trials, several experts and regulatory groups (e.g., European Medicines Agency, US Food and Drug Administration) only recommend the use of ESAs in patients receiving treatment with palliative intention [2, 28]. However, there are still no results from clinical trials or meta-analysis that have compared the use of ESAs in patients undergoing chemotherapy with different treatment goals (cure vs. palliation). A small randomized trial comparing the administration of epoetin beta (Hb target < 12 g/dl) to placebo in patients with lung and gynecologic cancers showed no difference in the incidence of thromboembolic events between the two groups [10]. Nevertheless, clinicians should carefully reconsider the use of ESA in patients with a high risk of thromboembolism (e.g., immobilization or history of thrombosis) [16].

Role of hemoglobin levels

According to a Cochrane meta-analysis, the higher number of thromboembolic events in patients receiving ESA was unrelated to baseline Hb levels [9], but available data also indicated a trend towards fewer thromboembolic events when treatment with ESA was initiated in patients with baseline Hb levels < 10 g/dl [29].

The current literature does not provide information about the optimal target Hb level. A meta-analysis of 12 randomized trials comparing epoetin beta with placebo could not provide evidence that high Hb values among patients treated with epoetin beta were associated with a higher risk of thromboembolic rates, disease progression, or mortality [30]. Although there is a lack of data concerning the optimal target Hb levels in anemic cancer patients receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy [17, 30], a target Hb > 12 g/dl might increase the risk of death and serious cardiovascular events. There is still a need of further clinical trials to determine target Hb levels in the use of ESAs in patients undergoing chemotherapy. Therefore, Hb levels should be raised to the lowest level necessary to achieve a reduction of RBC transfusion and relieve anemia-associated symptoms.

Conclusion

Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) are approved for the treatment of symptomatic anemia caused by treatment with myelosuppressive chemotherapy in patients with nonhematologic neoplasms in order to reduce the frequency of red blood cell (RBC) transfusions. Several randomized clinical trials have demonstrated that the use of ESAs is accompanied by serious side effects, such as an increase in thromboembolic events, mortality, and inferior outcomes. In order to decrease these risks, a baseline hemoglobin (Hb) level < 10 g/dl is mandatory before treatment initiation and Hb levels > 12 g/dl should be strictly avoided during administration. Clinicians must be aware of these issues and should carefully weigh the risks of ESAs against transfusion risks when considering the administration of these drugs in the individual patient.

References

Ludwig H, Van Belle S, Barrett-Lee P, Birgegård G, Bokemeyer C, Gascón P, et al. The European Cancer Anaemia Survey (ECAS): a large, multinational, prospective survey defining the prevalence, incidence, and treatment of anaemia in cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40(15):2293–306.

Bohlius J, Bohlke K, Castelli R, Djulbegovic B, Lustberg MB, Martino M, et al. Management of cancer-associated anemia with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents: aSCO/ASH clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15):1336–51.

Aapro M, Beguin Y, Bokemeyer C, Dicato M, Gascón P, Glaspy J, et al. Management of anaemia and iron deficiency in patients with cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines〈sup〉†〈/sup〉. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:iv96:iv110.

Hellström-Lindberg E, Gulbrandsen N, Lindberg G, Ahlgren T, Dahl IM, Dybedal I, et al. A validated decision model for treating the anaemia of myelodysplastic syndromes with erythropoietin + granulocyte colony-stimulating factor: significant effects on quality of life. Br J Haematol. 2003;120(6):1037–46.

Littlewood TJ, Zagari M, Pallister C, Perkins A. Baseline and early treatment factors are not clinically useful for predicting individual response to erythropoietin in anemic cancer patients. The Oncol. 2003;8(1):99–107.

Sekeres MA, Fu AZ, Maciejewski JP, Golshayan AR, Kalaycio ME, Kattan MW. A Decision analysis to determine the appropriate treatment for low-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Cancer. 2007;109(6):1125–32.

Park S, Grabar S, Kelaidi C, Beyne-Rauzy O, Picard F, Bardet V, et al. Predictive factors of response and survival in myelodysplastic syndrome treated with erythropoietin and G‑CSF: the GFM experience. Blood. 2008;111(2):574–82.

Mundle S, Lefebvre P, Vekeman F, Duh MS, Rastogi R, Moyo V. An assessment of erythroid response to epoetin alpha as a single agent versus in combination with granulocyte- or granulocyte-macrophage-colony-stimulating factor in myelodysplastic syndromes using a meta-analysis approach. Cancer. 2009;115(4):706–15.

Tonia T, Mettler A, Robert N, Schwarzer G, Seidenfeld J, Weingart O, et al. Erythropoietin or darbepoetin for patients with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12(12):Cd3407.

Fujisaka Y, Sugiyama T, Saito H, Nagase S, Kudoh S, Endo M, et al. Randomised, phase III trial of epoetin‑β to treat chemotherapy-induced anaemia according to the EU regulation. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(9):1267–72.

Cella D, Eton DT, Lai JS, Peterman AH, Merkel DE. Combining anchor and distribution-based methods to derive minimal clinically important differences on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) anemia and fatigue scales. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24(6):547–61.

Bohlius J, Tonia T, Nüesch E, Jüni P, Fey MF, Egger M, et al. Effects of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents on fatigue- and anaemia-related symptoms in cancer patients: systematic review and meta-analyses of published and unpublished data. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(1):33–45.

Chang J, Couture F, Young S, McWatters KL, Lau CY. Weekly epoetin alfa maintains hemoglobin, improves quality of life, and reduces transfusion in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(12):2597–605.

Pronzato P, Cortesi E, van der Rijt CC, Bols A, Moreno-Nogueira JA, de Oliveira CF, et al. Epoetin alfa improves anemia and anemia-related, patient-reported outcomes in patients with breast cancer receiving myelotoxic chemotherapy: results of a European, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. The Oncol. 2010;15(9):935–43.

Bennett CL, Silver SM, Djulbegovic B, Samaras AT, Blau CA, Gleason KJ, et al. Venous thromboembolism and mortality associated with recombinant erythropoietin and darbepoetin administration for the treatment of cancer-associated anemia. JAMA. 2008;299(8):914–24.

Gao S, Ma JJ, Lu C. Venous thromboembolism risk and erythropoiesis-stimulating agents for the treatment of cancer-associated anemia: a meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(1):603–13.

Aapro M, Scherhag A, Burger HU. Effect of treatment with epoetin-beta on survival, tumour progression and thromboembolic events in patients with cancer: an updated meta-analysis of 12 randomised controlled studies including 2301 patients. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(1):14–22.

Bohlius J, Schmidlin K, Brillant C, Schwarzer G, Trelle S, Seidenfeld J, et al. Recombinant human erythropoiesis-stimulating agents and mortality in patients with cancer: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373(9674):1532–42.

Wright JR, Ung YC, Julian JA, Pritchard KI, Whelan TJ, Smith C, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of erythropoietin in non-small-cell lung cancer with disease-related anemia. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(9):1027–32.

Leyland-Jones B, Semiglazov V, Pawlicki M, Pienkowski T, Tjulandin S, Manikhas G, et al. Maintaining normal hemoglobin levels with epoetin alfa in mainly nonanemic patients with metastatic breast cancer receiving first-line chemotherapy: a survival study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(25):5960–72.

Glaspy J, Crawford J, Vansteenkiste J, Henry D, Rao S, Bowers P, et al. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents in oncology: a study-level meta-analysis of survival and other safety outcomes. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(2):301–15.

Tonelli M, Hemmelgarn B, Reiman T, Manns B, Reaume MN, Lloyd A, et al. Benefits and harms of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents for anemia related to cancer: a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2009;180(11):E62–71.

Henke M, Laszig R, Rübe C, Schäfer U, Haase KD, Schilcher B, et al. Erythropoietin to treat head and neck cancer patients with anaemia undergoing radiotherapy: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;362(9392):1255–60.

Thomas G, Ali S, Hoebers FJ, Darcy KM, Rodgers WH, Patel M, et al. Phase III trial to evaluate the efficacy of maintaining hemoglobin levels above 12.0 g/dL with erythropoietin vs above 10.0 g/dL without erythropoietin in anemic patients receiving concurrent radiation and cisplatin for cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108(2):317–25.

Shenouda G, Zhang Q, Ang KK, Machtay M, Parliament MB, Hershock D, et al. Long-term results of radiation therapy oncology group 9903: a randomized phase 3 trial to assess the effect of erythropoietin on local-regional control in anemic patients treated with radiation therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;91(5):907–15.

Leyland-Jones B, Bondarenko I, Nemsadze G, Smirnov V, Litvin I, Kokhreidze I, et al. A Randomized, Open-Label, Multicenter, Phase III Study of Epoetin Alfa Versus Best Standard of Care in Anemic Patients With Metastatic Breast Cancer Receiving Standard Chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(11):1197–207.

Singh AK, Szczech L, Tang KL, Barnhart H, Sapp S, Wolfson M, et al. Correction of anemia with epoetin alfa in chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(20):2085–98.

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=3&id=1493. Accessed 29 May 2023.

Grant MD, Piper M, Bohlius J, Tonia T, Robert N, Vats V, et al. AHRQ comparative effectiveness reviews. Epoetin and Darbepoetin for managing anemia in patients undergoing cancer treatment: comparative effectiveness update. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013.

Aapro M, Osterwalder B, Scherhag A, Burger HU. Epoetin-beta treatment in patients with cancer chemotherapy-induced anaemia: the impact of initial haemoglobin and target haemoglobin levels on survival, tumour progression and thromboembolic events. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(12):1961–71.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Paracelsus Medical University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

R. Heregger declares travel, accommodations, and expenses from Pharmamar. R. Greil declares honoraria, and consulting or advisory role for Celgene, Roche, Merck, Takeda, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Amgen, BMS, MSD, Sandoz, AbbVie, Gilead, and Daiichi Sankyo, and travel, accommodations and expenses from Roche, Amgen, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Novartis, MSD, Celgene, Gilead, BMS, and AbbVie.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Heregger, R., Greil, R. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents—benefits and harms in the treatment of anemia in cancer patients. memo 16, 259–262 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12254-023-00902-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12254-023-00902-4