Abstract

Real-world evidence from clinical practices is fundamental for understanding the efficacy and tolerability of medicinal products. Patients with renal cell cancer were studied to gain data not represented by analyses conducted on highly selected patients participating in clinical trials. Our goal was to retrospectively collect data from patients with advanced renal tumours treated with pazopanib (PZ) to investigate the efficacy, frequency of side effects, and searching for predictive markers. Eighty-one patients who had received PZ therapy as first-line treatment were retrospectively evaluated. Overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS) were assessed as endpoints. Median PFS and OS were 11.8 months (95% CI: 8.8–22.4); and 30.2 months (95% CI: 20.3–41.7) respectively. Severe side effects were only encountered in 11 (14%) patients. The presence of liver metastasis shortened the median PFS (5.5 vs. 14.8 months, p = 0.003). Median PFS for patients with or without side effects was 25.6 vs. 7.3 months, respectively (p = 0.0001). Patients younger than 65 years had a median OS of 41.7 months vs. 25.2 months for those over 65 years of age (p = 0.008). According to our results absence of liver metastases, younger age (<65 years) and presence of side effects proved to be independent predictive markers of better PFS and OS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Renal cell cancer represents only 2% of all cancer diseases [1], however, it comprises 90% of all renal-originated tumors [2]. 25–30% of patients already have distant metastases at the time of diagnosis, and further 25–30% of those who initially are resectable eventually recur and develop distant metastases [2]. Consequently, the overall five-year survival is as low as 20–25%. [3].

The breakthrough in the treatment of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) was the introduction of small-molecular-weight tyrosine-kinase inhibitors (TKI) of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signalling pathway (sunitinib, sorafenib, pazopanib), which inhibit the intracellular domain of VEGF receptors. Although the range of therapeutic options has broadened due to the introduction of immunotherapeutic modalities and their combinations, these medications will continue to play a crucial role in the treatment of renal tumours and their future status will be determined by ongoing clinical trials.

Pazopanib is an oral, multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor with effect on VEGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) and the c-Kit tyrosine kinases [4]. In a phase III clinical study, 450 patients with or without previous cytokine therapy were randomized to pazopanib and placebo treatment arms [5]. Patients had mostly good or intermediate prognosis. Pazopanib significantly increased the progression-free survival (PFS) compared to placebo (9.2 vs. 4.2 months, HR: 0.46, 95% CI: 0.34–0.62). This increased PFS was noted in both groups of patients, with or without previous treatment. An improvement in OS was also achieved (21.1 vs. 18.7 months), but the difference was not significant as cross-over was allowed from placebo to pazopanib arm (HR in mortality was 0.91, 95% CI 0.71–1.16) [6]. The treatment was well tolerated, the most common side effects, similarly to the other TKIs, were diarrhoea, hypertension, hair colour change, nausea, anorexia and vomiting. Clinically significant elevated liver function developed in 10% of patients with occasional dose reductions being necessary, however, haematological toxicity was observed only in 1% of patients. Based on the results of the phase III study, pazopanib has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in October 2009 [7], and in February 2010 it gained European Medicines Agency (EMA) approval as well [8]. In a subsequent, phase III non-inferiority COMPARZ study, pazopanib was shown to be comparable in efficacy to sunitinib [9, 10], and in a quality of life (HRQoL) comparative study (PISCES), pazopanib was proved to be better tolerated than sunitinib [11].

A large patient database was studied retrospectively, with the current study aiming to define patient traits contributing to effective pazopanib treatment, based on everyday clinical practice. The purpose of the study was to analyse efficacy and tolerability of pazopanib, with the aspiration of determining the factors responsible for longer PFS and OS.

Methods

Patients

In the present study, we processed data from 2013 to 2019 on renal tumour patients treated with PZ at the Department of Genitourinary Medical Oncology and Clinical Pharmacology of the National Institute of Oncology. The study was approved by the Medical Research Council: (21679–2/2016), and by the Ethical Committee of the institute.

Between 11th May 2013 and 13rd March 2019, 157 patients had their PZ treatment initiated. Out of the 157 patients, we evaluated the data of the 81 patients who received PZ treatment in the first line setting, who underwent nephrectomy and had pure clear cell histology.

For the retrospective data analysis patients’ data were extracted from the electronic database of the institute. In all cases, the initial dose of PZ was consecutively 800 mg/day. Dose reduction or delay was performed at the oncologist’s discretion, based on the severity of side effects. Treatment was continued until disease progression based on RECIST 1.1 (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors), intolerable toxicity, or until death. Tumour response was assessed by CT or MRI every 12 weeks, and adverse events were evaluated according to CTCAE 4.0 and 5.0 (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events).

Statistical Analysis

PFS was calculated from the start of the PZ treatment until disease progression or death, or, if there was no progression, until the last follow-up date, while OS was calculated from the start of the treatment until death or the end of the follow-up period. PFS and OS were evaluated by Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test. Parameters significant in univariate evaluation were selected for multivariate Cox regression analysis. For the significance level p < 0.05 was applied. All analyses have been conducted with the NCSS12 software [NCSS 12 Statistical Software (2018), NCSS, LLC. Kaysville, UT, USA, ncss.com/software/ncss].

Results

Patient Characteristics

Patients’ characteristics were detailed in Table 1. The mean age of patients was 65.3 years (range 40–85 years) and the male to female ratio was 1.9:1. Prognosis has been graded according to the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) guidelines [12] (Table 1). Most of the patients belonged to the moderate prognostic group, while the second largest group had good prognosis. All patients underwent nephrectomy and 19 patients (23%) had metastasectomy (Table 2). In 36 cases, the metastases were identified along with the diagnosis of the primary tumour (synchronous), meanwhile in 45 cases, it developed later (metachronous) (Table 1).

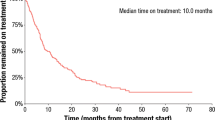

The Efficacy of the Treatment, Predictive Factors, and Side Effects

The mean duration of pazopanib therapy was 16.1 months (median 8.7, range 0.3–103.9 months). Dose reduction due to adverse events occurred in 20 cases (25%), treatment discontinuation took place in 11 cases (14%) (Table 2). At the end of follow-up on October 1, 2019, seventeen patients were still receiving PZ therapy, the remaining of the patients had the treatment stopped mainly due to progression (N = 48) or death (N = 16). The best response was complete remission (CR) in 9 (11%) cases, partial remission (PR) in 24 (30%), stable disease (SD) in 28 (35%), and progression developed in 6 (7%) cases. Fourteen patients (17%) were not evaluated, or the assessment was not available. Further treatments and additional therapies following PZ therapy are also listed in Table 2. Severe, grade 3/4 side effects were rarely presented, only in 11 (14%) patients, meanwhile, 32 (39%) of patients did not present any adverse event. Adverse events are detailed in Table 3.

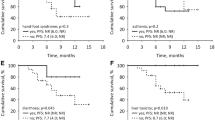

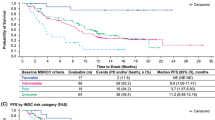

After a median of 43.0 months of follow up, the median PFS was 11.8 months and the median OS was 30.2 months (Fig. 1). The median PFS was shorter in patients with liver metastasis (Table 4, Fig. 2). Moreover, PFS was found to be shorter in patients without remission or side effects (Table 4, Figs. 3 and 4). Dose reduction and among side effects, diarrhoea proved to be predictive factors, however they were not independent markers of PFS (Table 4). In univariate analysis, PFS was found to be longer in patients who underwent dose reduction (Table 4).

The OS was significantly influenced by age, presence of liver metastasis, experienced side effects, and best treatment response (Table 4, Figs. 5 and 6). Patients who were in good, moderate and poor prognostic groups had different median OS: 31.5 (23.2–46) (N = 35), 26.2 (12.9–40) (37) and 6.2 (2.9–6.2) (N = 7) months, respectively (p = 0.02).

Discussion

The present study has been conducted at one site between 2013 and 2019 and includes the retrospective data analysis of patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma receiving PZ therapy.

Our patients with renal cancer were from the older age group (median age: 65.3 years), which is typical in RCC. The 1.9:1 male: female ratio also seems to be consistent with the international standards of male dominance in RCC [13]. Our patients presented 11.8 months median PFS and 30.2 months median OS, which is somewhat better than the results of registrational clinical trials (PFS: 9.2; OS: 22.9 months) [5, 6]. We have to mention that our patient cohort was more homogeneous, all of them underwent radical nephrectomy, and had pure clear cell histology. On the other hand, patient outcome observed in our study is similar to the results of published scientific papers (PFS: 4.6–12.4 months, OS: 21–29.9 months) [10, 14,15,16]. A Korean study presented a 40 months median OS [17], however, the authors did not explain the reasons for the unusually long survival.

With regard to the best response, the objective tumour response ratio of 33% which is similar to the registrational study (32.4%) [6], the COMPARZ study (31%) [10], or the PRINCIPAL study (30%) [15].

In Hungary, there are two types of reimbursed treatments available for advanced renal cell cancer in first line: sunitinib and pazopanib. The prospective, randomized non-inferiority COMPARZ study presented their efficacy to be close to identical [9, 10] Other retrospective studies showed similar [17] or contradictory results [16]. While according to the PISCES [11] and a Korean retrospective study [17], the PZ therapy is better tolerated by the patients. In the present study, the PZ treatment was well tolerated, severe (grade 3/4) side effects were rarely reported (only 14%), while 43% of patients did not present any adverse effect. The most common side effects were diarrhoea (35%), fatigue (17%), hypertension (14%), nausea/vomiting (10%), and decreased liver function (7%), while the most commonly reported side effects in the registrational trial were diarrhoea (52%), hypertension (40%), hair colour change (38%), and nausea (26%). Decreased liver function was present in 53% of patients [6]. A suggested potential reason for this controversy is that in the everyday practice, the side effects are not as systematically registered as they are in the randomized, prospective clinical trials. Twenty-five percent of patients had dose reduction, which refers to the frequency of the side effects. Higher or similar ratios have been published in the literature: in the comparative study of Motzer et al. (44%) [9], a Korean study (41%) [17], a Hungarian study (28.9%) [14], while in the PISCES study, the reported ratio was 13%, however in that study PZ was administered only for 10 weeks. The low dose reduction ratio also refers to good tolerability.

In this study the factors influencing survival were also investigated. Improved PFS and OS were observed in patients who did not have liver metastasis (p = 0.003 and p = 0.0004, respectively). The significance of liver metastasis was also highlighted by Kim et al. [17], nevertheless in their study, bone metastasis also caused worse outcome. Improved outcome was presented in our patients with complete or partial tumour response (p = 0.007). Similarly to other TKI therapies [18,19,20], the presence of side effects was a strong predictive marker of significantly longer PFS: all side effects (p = 0.0001), diarrhoea (p = 0.016). Dose reductions were observed to result in improved PFS (p = 0.016), which also indicates the significance of side effects. Increased OS was detected in patients who were under 65 years old (p = 0.008), presumably because co-morbidities and drug-drug interactions complicate the treatment of the elderly.

According to the literature, our study analysed the highest patient number from one centre, which is the strength of this study, meanwhile the weakness of the analysis is its retrospective nature.

Based on the present data, first-line pazopanib therapy for advanced RCC, even in unselected patients, is suggested to be an efficient, well tolerated treatment. Both OS and PFS were significantly improved by the absence of liver metastases. The presence of side effects proved to be an independent predictive marker of PFS, while younger age (<65 years) and objective response were independent markers of longer OS.

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 68:394–424

National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology, 2019

Mihaly Z, Sztupinszki Z, Surowiak P, Gyorffy B (2012) A comprehensive overview of targeted therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 12:857–872

Sloan B, Scheinfeld NS (2008) Pazopanib, a VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor for cancer therapy. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 9:1324–1335

Sternberg CN, Davis ID, Mardiak J, Szczylik C, Lee E, Wagstaff J, Barrios CH, Salman P, Gladkov OA, Kavina A, Zarbá JJ, Chen M, McCann L, Pandite L, Roychowdhury DF, Hawkins RE (2010) Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 28:1061–1068

Sternberg CN, Hawkins RE, Wagstaff J, Salman P, Mardiak J, Barrios CH, Zarba JJ, Gladkov OA, Lee E, Szczylik C, McCann L, Rubin SD, Chen M, Davis ID (2013) A randomised, double-blind phase III study of pazopanib in patients with advanced and/or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: final overall survival results and safety update. Eur J Cancer 49:1287–1296

Administration FaD (2009) NDA Approval

Nieto M, Borregaard J, Ersboll J, ten Bosch GJA, van Zwieten-Boot B, Abadie E, Schellens JHM, Pignatti F (2011) The European medicines agency review of pazopanib for the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma: summary of the scientific assessment of the Committee for Medicinal Products for human use. Clin Cancer Res 17:6608–6614

Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Cella D, Reeves J, Hawkins R, Guo J, Nathan P, Staehler M, de Souza P, Merchan JR, Boleti E, Fife K, Jin J, Jones R, Uemura H, De Giorgi U, Harmenberg U, Wang J, Sternberg CN, Deen K, McCann L, Hackshaw MD, Crescenzo R, Pandite LN, Choueiri TK (2013) Pazopanib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 369:722–731

Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, McCann L, Deen K, Choueiri TK (2014) Overall survival in renal-cell carcinoma with pazopanib versus sunitinib. N Engl J Med 370:1769–1770

Escudier BPC, Bono P (2014) Randomized, controlled, double-blind, cross-over trial assessing treatment preference for pazopanib versus sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: PISCES study. J Clin Oncol 32:1412–1418

Motzer RJ, Mazumdar M, Bacik J, Berg W, Amsterdam A, Ferrara J (1999) Survival and prognostic stratification of 670 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 17:2530–2540

Woldrich JM, Mallin K, Ritchey J, Carroll PR, Kane CJ (2008) Sex differences in renal cell cancer presentation and survival: an analysis of the National Cancer Database, 1993–2004. J Urol 179:1709–1713

Maráz A, Bodrogi I, Csejtei A, Dank M, Géczi L, Küronya Z, Mangel L, Petrányi A, Szűcs M, Bodoky G (2013) First Hungarian experience with pazopanib therapy for patients with metastatic renal cancer. Magy Onkol 57:173–176

Schmidinger M, Bamias A, Procopio G, Hawkins R, Sanchez AR, Vázquez S, Srihari N, Kalofonos H, Bono P, Pisal CB, Hirschberg Y, Dezzani L, Ahmad Q, Jonasch E, PRINCIPAL Study Group (2019) Prospective observational study of pazopanib in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (PRINCIPAL study). Oncologist 24:491–497

Nazha S, Tanguay S, Kapoor A, Jewett M, Kollmansberger C, Wood L, Bjarnason G, Heng D, Soulières D, Reaume N, Basappa N, Lévesque E, Dragomir A (2018) Use of targeted therapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: clinical and economic impact in a Canadian real-life setting. Curr Oncol 25:e576–e584

Kim MS, Chung HS, Hwang EC, Jung SI, Kwon DD, Hwang JE, Bae WK, Park JY, Jeong CW, Kwak C, Song C, Seo SI, Byun SS, Hong SH, Chung J (2018) Efficacy of first-line targeted therapy in real-world Korean patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: focus on sunitinib and pazopanib. J Korean Med Sci 33:e325

Nagyiványi K, Budai B, Bíró K, Gyergyay F, Noszek L, Küronya Z, Németh H, Nagy P, Géczi L (2016) Synergistic survival: a new phenomenon connected to adverse events of first line sunitinib treatment in advanced renal cell carcinoma. Clin Genitourin Cancer 14:314–322

Maráz A, Cserháti A, Uhercsák G, Szilágyi E, Varga Z, Kahán Z (2014) Therapeutic significance of sunitinib-induced "off-target" side effects. Magy Onkol 58:167–172

Di Fiore F, Rigal O, Ménager C, Michel P, Pfister C (2011) Severe clinical toxicities are correlated with survival in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib and sorafenib. Br J Cancer 105:1811–1813

Funding

Open access funding provided by National Institute of Oncology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Mihály Dániel Szőnyi, Krisztián Nagyiványi, Fruzsina Gyergyay, Lajos Géczi, Barna Budai and Tamás Martin. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Zsófia Küronya, Andrea Ladányi, Edina Kiss and Krisztina Biró and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval (include appropriate approvals or waivers)

The study was approved by the Medical Research Council (21679–2/2016).

Availability of Data and Material (Data Transparency)

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent to Participate

N/A.

Code Availability

N/A.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Küronya, Z., Szőnyi, M.D., Nagyiványi, K. et al. Predictive Markers of First Line Pazopanib Treatment in Kidney Cancer. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 26, 2475–2481 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12253-020-00853-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12253-020-00853-9