Abstract

This study aims to introduce a measure of Financial Resilience for evaluating its influence on financial well-being amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Financial Resilience, in this context, pertains to an individual's capacity to adapt, cope, and financially recover in the face of the new challenges posed by an economic downturn. We conducted a survey among 591 Brazilian citizens in 2021 and employed Structural Equation Modeling to examine the relationships between various constructs and validate our proposed measure of Financial Resilience. Our findings reveal a negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Financial Resilience, resulting in heightened uncertainty and insecurity concerning individuals' financial future during this period. Notably, those with lower Financial Resilience were found to be the most financially vulnerable during the pandemic. These results provide valuable insights into the measurement of financial contingencies faced by the population and can be useful to policy and governmental strategies aimed at mitigating the social, economic, and financial repercussions of economic downturns. Fostering Financial Resilience and reducing vulnerability among lower-income individuals are critical objectives, particularly in times of economic uncertainty. While the concept of Financial Resilience is of paramount importance, the literature on this subject remains relatively nascent, with ongoing developments in measurement instruments. In this regard, our study contributes by proposing a concise measure of Financial Resilience through two simple questions.

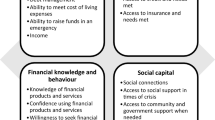

Source: Prepared by the authors (2023)

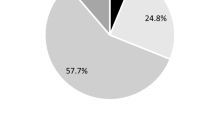

Source: Survey data (2023)

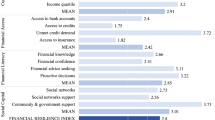

Source: Prepared by the authors (2023)

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Barrafrem K, Västfjäll D, Tinghög G (2020a) Financial Homo Ignorans: measuring vulnerability to behavioral biases in household finance. J Behav Exp Finance 28:1–42. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/q43ca

Barrafrem K, Västfjäll D, Tinghög G (2020b) Financial well-being, COVID-19, and the financial better-than-average-effect. J Behav Exp Financ 28(1–5):100410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jFWB.2020.100410

Barrett AM, Hogreve J, Brüggen EC (2021) Coping with governmental restrictions: the relationship between stay-at-home orders, resilience, and functional, social, mental, physical, and financial well-being. Front Psychol 11(1–16):3996. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577972

Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (2021) Projections and estimates of the population of Brazil and the Federation Units. São Paulo. https://www.ibge.gov.br/apps/populacao/projecao/index.html

Brüggen EC, Hogreve J, Holmlund M, Kabadayi S, Löfgren M (2017) Financial well-being: a conceptualization and research agenda. J Bus Res 79:228–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.03.013

Chhatwani M, Mishra SK (2021) Does financial literacy reduce financial fragility during COVID-19? The moderation effect of psychological, economic and social factors. Int J Bank Mark 39:1114–1133. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-11-2020-0536

Clark RL, Mitchell OS (2022) Americans’ financial resilience during the pandemic. Financ Plan Rev 5:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/cfp2.1140

Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (2019) Toward a new impact narrative for financial inclusion. Washington, D.C. https://www.cgap.org/research/publication/toward-newimpact-narrative-financial-inclusion

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (2015) Measuring financial well-being: a guide to using the CFPB financial well-being scale. CFPB, Washington, DC. https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201512_cfpb_financial-well-being-user-guide-scale.pdf

Delafrooz N, Paim LH (2011) Determinants of financial wellness among Malaysia workers. Afr J Bus Manag 5:10092. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM10.1267

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18:39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Friedline T, Chen Z, Morrow SP (2021) Families’ financial stress and well-being: the importance of the economy and economic environments. J Fam Econ Issues 42:34–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09694-9

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE (2014) Multivariate data analysis. Pearson Education, London

Hecksher MD, Foguel MN (2020) Technical Note 66—Emergency benefits for informal and formal workers in Brazil: estimates of the combined coverage rates of Law No. 13,982/2020 and Provisional Measure No. 936/2020. 1–22. https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/biblio-1102239

Holling CS (1973) Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 4:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000245

Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen M (2008) Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit. Electron J Bus Res Methods 6:53–60

Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model 6:1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

International Monetary Fund (2021) World economic outlook update. Falt Lines Widen in the global recovery. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2021/07/27/world-economic-outlook-update-july-2021#Overview

Jayasinghe M, Selvanathan EA, Selvanathan S (2020) The financial resilience and life satisfaction nexus of indigenous Australians. Econ Pap J Appl Econ Policy 39:336–352. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-3441.12296

Joo S (2008) Personal financial wellness. In: Xiao JJ (ed) Handbook of consumer finance research. Springer, New York, pp 21–33

Joo SH, Grable JE (2004) An exploratory framework of the determinants of financial satisfaction. J Fam Econ Issues 25:25–50. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JEEI.0000016722.37994.9f

Kass-Hanna J, Lyons AC, Liu F (2022) Building financial resilience through financial and digital literacy in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Emerg Mark Rev 51:1–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2021.100846

Klapper L, Lusardi A (2020) Financial literacy and financial resilience: evidence from around the world. Financ Manag 49:589–614. https://doi.org/10.1111/fima.12283

Kline RB (2015) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications, New York

Kunkel FIR, Vieira KM, Potrich ACG (2015) Causes and consequences of credit card debt: a multifactor analysis. Manag Mag 50:169–182. https://doi.org/10.5700/rausp1192

Lee JM, Lee J, Kim KT (2020) Consumer financial well-being: knowledge is not enough. J Fam Econ Issues 41:218–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-019-09649-9

Lusardi A, Hasler A, Yakoboski PJ (2021) Building up financial literacy and financial resilience. Mind Soc 20:181–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/fima.12283

Mahendru M (2021) Financial well-being for a sustainable society: a road less travelled. Qual Res Org Manag Int J 16:572–593. https://doi.org/10.1108/QROM-03-2020-1910

Ministry of Health (2022) Coronavirus panel. https://covid.saude.gov.br/.

Moore D, Niazi Z, Rouse R, Kramer B (2019) Building resilience through financial inclusion: a review of existing evidence and knowledge gaps. Financial Inclusion Program, Innovations for Poverty Action https://www.poverty-action.org/sites/default/files/publications/Building-Resiliencethrough-Financial-Inclusion-English.pdf

National Confederation of Commerce of Goods, Services and Tourism (2021) National Consumer Debt and Default Survey (PEIC). https://portal-bucket.azureedge.net/wp-content/2021/05/Analise-Peic-maio-2021.pdf

Netemeyer RG, Warmath D, Fernandes D, Lynch JG Jr (2018) How am I doing? Perceived financial well-being, its potential antecedents, and its relation to overall well-being. J Consum Res 45:68–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucx109

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development-OECD (2021) OECD Economic Outlook. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/a321e0c1-en.pdf?expires=1629070308&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=7A77F2DDC4FA1978FD72AE47C4ED497C

Pan American Health Organization (2021) Fact sheet on Covid-19. https://www.paho.org/pt/covid19

Pijoh LFA, Indradewa R, Syah TYR (2020) Financial literacy, financial behaviour and financial anxiety: Implication for financial well being of top management level employees. J Multidiscip Acad 4:381–386

Porter NM (1990) Testing a model of financial wellbeing. Financ Couns Plan 4:135–164

Potrich ACP, Vieira KM, Ceretta PS (2013) Level of financial literacy of university students: after all, what is relevant? Electron J Admin Sci 12:314–333. https://doi.org/10.5329/RECADM.2013025

Salignac F, Muir K, Wong J (2016) Are you really financially excluded if you choose not to be included? Insights from social exclusion, resilience and ecological systems. J Soc Policy 45:269–286. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279415000677

Salignac F, Marjolin A, Reeve R, Muir K (2019) Conceptualizing and measuring financial resilience: a multidimensional framework. Soc Indic Res 145:17–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02100-4

Salignac F, Hanoteau J, Ramia I (2022) Financial resilience: a way forward towards economic development in developing countries. Soc Indic Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02793-6

Sorgente A, Lanz M (2019) The multidimensional subjective financial well-being scale for emerging adults: development and validation studies. Int J Behav Dev 43:466–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025419851859

Taft MK, Hosein ZZ, Mehrizi SMT, Roshan A (2013) The relation between financial literacy, financial wellbeing and financial concerns. Int J Bus Manag 8:63. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v8n11p63

Tahir MS, Shahid AU, Richards DW (2022) The role of impulsivity and financial satisfaction in a moderated mediation model of consumer financial resilience and life satisfaction. Int J Bank Mark 40:773–790. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-09-2021-0407

Vera-Toscano E, Ateca-Amestoy V, Serrano-Del-Rosal R (2006) Building financial satisfaction. Soc Indic Res 77:211–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-2614-3

Vieira KM, Klein LL, Bressan AA, Pereira BAD, Marzzoni DNS, Batista FSRG (2021a) Loss of financial well-being in the Covid-19 pandemic: first evidences from a Websurvey. Health Res 14:787–796. https://doi.org/10.17765/2176-9206.2021v14n4e9020

Vieira KM, Bressan AA, Fraga LS (2021b) Financial well-being of Minha Casa Minha Vida beneficiaries: perception and background. RAM Mackenzie Manag Mag 22:1–40. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-6971/eramg210115

Vieira KM, Potrich ACG, Bressan AA, Klein LL (2021c) Loss of financial well-being in the COVID-19 pandemic: does job stability make a difference? J Behav Exp Financ 31(1–12):100554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jFWB.2021.100554

Xiao JJ, Sorhaindo B, Garman ET (2006) Financial behaviours of consumers in credit counselling. Int J Consum Stud 30:108–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2005.00455.x

Zokaityte A (2017) Financial crisis and the money guidance service: building consumer financial resilience. In: Zokaityte A (ed) Financial literacy education: edu-regulating our saving and spending habits. Springer, Cham, pp 237–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55017-6_7

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CVB: conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; software; supervision; validation; visualization; roles/writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. AAB, KMV, TKM: conceptualization; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; software; validation; roles/writing—original draft; writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1: Methodological procedures for validating the constructs of loss of financial well-being and financial ignorance

Appendix 1: Methodological procedures for validating the constructs of loss of financial well-being and financial ignorance

The first validated construct pertains to the loss of financial well-being. Upon analyzing the initial measurement model for the FWB loss construct, it was observed that all variables were significant at the 1% level and exhibited satisfactory factor loadings (values exceeding 0.50). However, during model estimation, it became apparent through the analysis of fit indices that the model fit was inadequate, as displayed in Table 10. Thus, the "Initial Model" column presents the results of the model prior to correlation adjustments, while the "Final Model" column indicates the results of fit indices for the final estimation, which includes the inserted correlations. Additionally, Fig. 4 presents the coefficients of the scale items, the correlations, and their respective significances.

To achieve a better-fitting model, the chosen improvement strategy was characterized by the gradual inclusion of correlations between the errors of observable variables that made theoretical sense.

The first correlation introduced was between errors e6 and e7. These questions pertain to respondents' perception of future financial security during the pandemic. Therefore, the theoretical rationale for this correlation is that these questions share common measurement errors, as respondents who have difficulty identifying their perception of financial security lasting until the end of their life (Q06) during the pandemic period will also have difficulty perceiving that they are financially secure until the end of their life (Q07).

Next, correlations were introduced between errors e3 and e4 and between errors e4 and e5. Items 3 and 4 also relate to respondents' perception of becoming financially secure during the pandemic (item 3) and the perception that interviewees are securing their financial future (item 4). Respondents' perceptions of securing their financial future during the pandemic (item 4) are also associated with the possibility of achieving the financial goals they have set (item 5).

The next established correlation was between errors e10 and e12. Questions related to these errors concern people's perception that finances control their lives (item 10) and consequently, they cannot enjoy life because they worry too much about money (item 12).

Continuing with the adjustments, correlations were included between errors e3 and e5 and between e11 and e12, and e9 and e10. The relationship between the first two errors is that respondents' perception of "becoming financially secure during the pandemic" (item 3) is related to the possibility of achieving the financial goals they have set (item 5). On the other hand, errors e11 and e12 inquire about people's perception that finances control their lives during the pandemic (item 11), i.e., how much people perceive that they do not have control over their lives is related to their perception of being able to deal with unexpected events that may disrupt their financial control (item 12). Meanwhile, respondents' perception of their ability to keep their financial life in order during the pandemic (item 9) is associated with their perception that their finances control their life (item 10) during this period.

Finally, a correlation was included between errors e8 and e12. The relationship between these errors is based on the assumption that respondents who, due to their financial situation, will never have the things they want in life (item 8) also cannot enjoy life because they worry too much about financial matters (item 12), especially during pandemic periods.

Following these additions, the model exhibited appropriate fit indices, as demonstrated in the "Final Model" column of Table 10. The final measurement model of the construct loss of financial well-being and the correlations established to obtain the adjusted model are shown in Fig. 4.

For the financial ignorance construct, the individual components of the first-order model were initially validated, followed by the validation of the final measurement model of the construct. Therefore, Table 11 displays the fit statistics of the first-order components.

From the analysis, it is evident that the Decision Avoidance and Motivated Reasoning constructs are deemed adequate. Conversely, the Avoidance/Evasion of Information construct exhibited significant chi-square statistics, as the chi-square/degrees of freedom ratio exceeded 5 and the RMSEA value surpassed 0.06. Additionally, the Aggregation Bias construct had an AVE value lower than 0.5. Consequently, no adjustments were feasible to enhance these models, given that these constructs consist of only three variables. The unidimensionality and reliability of the constructs were verified in line with the established criteria in the literature.

Subsequent to the validation process, our aim was to evaluate the discriminant validity of the constructs by comparing the AVE with the correlations between the constructs, as evidenced in the correlations presented in Table 12.

The correlation values between the constructs are lower than the square root of the AVE (represented by the diagonal values highlighted in italics), which indicates the discriminant validity of the constructs. Additionally, all the correlation values between the constructs were less than 0.85, underscoring that each construct represents distinct dimensions of financial ignorance.

Subsequently, the validation of the second-order model for the financial ignorance construct was conducted (Table

13).

It is observed that the initial model proposed for measuring financial ignorance is inadequate. To obtain an adjusted measurement model, the same strategy presented earlier was employed, involving the insertion of correlations between the errors of the observed variables, which made theoretical sense. In this case, just two correlations were needed for the model to become adequate, as illustrated in Fig.

Initial and final measurement model of the financial ignorance scale with the respective standardized coefficients and the significance of each variable. Note(s): *** Significant at the 1% level. 1z-value not calculated, where the parameter was set to 1, due to the requirements of the model. Source(s): Research results (2023)

5.

Following the inclusion of these correlations, the final measurement model demonstrated suitable fit indices, as depicted in Fig. 3. It is important to highlight that all relationships within the second-order model for the financial ignorance construct were statistically significant at the 1% level. Among these dimensions, Information Avoidance (0.890), Decision Avoidance (0.771), and Aggregation Bias (0.738) had the most substantial impact on financial ignorance.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Brasil, C.V., Bressan, A.A., Vieira, K.M. et al. Financial Resilience, Financial Ignorance, and their impact on financial well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from Brazil. Int Rev Econ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-023-00443-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-023-00443-6