Abstract

Non-Profit Organizations (NPOs) find themselves in a very competitive environment, as everyday consumers are constantly exposed to numerous advertisements; thus, they must find ways to capture consumers’ attention. The objective of this study is to explore how the different elements (image, text, logo) of print advertisements of NPOs using different emotional appeals (positive and negative) of a familiar and unfamiliar brand influence donation behaviour and the attitude toward the ad (Aad). Using eye-tracking technology and a survey, we conducted two experiments, one with unfamiliar brands of NPOs and another with a familiar brand. The results showed the advertisement areas on which participants fixated and their relationship with participants’ attitude towards the advertisement and donation behaviour. For unfamiliar NPOs, the less time it took the participant to first fixate on the logo area, the more positive attitude toward the ad when the advertisement used a negative frame. Also, participants spent more time in the image area of negatively framed ads when they had a more positive attitude toward the ad. On the other hand, for a familiar brand, the time to first fixate on the logo area had a negative correlation with the donation behaviour, indicating that the less time it takes to first fixate on the logo area, the more participants chose to donate.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The non-profit sector plays an important role in providing social services in different areas such as education, health, and social welfare (Zemack-Rugar & Klucarova-Travani, 2018). It is a growing sector due to the increasing need to improve the life of people in need, helping through aid and monetary donations (Bilgin & Kethüda, 2022). Even though Non-Profit Organizations (NPOs) are a vital part of society, as they work to improve the lives of others and help those in need, they face a significant challenge due to their dependency on donations from individuals, commercial organizations, and public aid to achieve their goals. Thus, they experience fierce competition for limited resources (Septianto & Paramita, 2021).

NPOs are facing a reduction in their incomes mainly due to the withdrawal of public aid (Septianto et al., 2020), making individual donors one of their principal sources of income (Hibbert, 2016). Furthermore, they are required to demonstrate their impact not only on the beneficiaries but also on society, making it more difficult to obtain resources. Therefore, most NPOs rely on advertising to motivate donors to give either money or time (Zhang et al., 2019). Thus, many NPOs use emotional appeals in their advertisements to promote their causes and encourage donations (Conlin & Bauer, 2022). However, nowadays, there is no consensus on how NPOs’ advertisements impact donor behaviour and, more specifically, regarding the effectiveness of using emotional appeals to capture attention, enhance attitude toward the ad (Aad), and motivate donation behaviour.

NPOs usually use print advertisements, which require the audience to view graphic illustrations and read a message. In print advertisements, mainly three elements are used: image, text, and brand (Pieters & Wedel, 2004). Also, most NPOs’ advertisements use emotional appeals (positive and negative), as they have proven to be an effective persuasion tool (Li & Yin, 2022; Yousef et al., 2022; Septianto & Tjiptono, 2019).

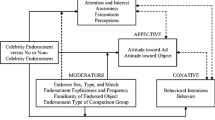

According to Pieters et al. (2010), to process stimuli, the first step is to be aware of them. So, for an advertisement to be effective, first, it must capture the audience’s attention because once people pay attention, they might be affected by an ad. Therefore, it is crucial to identify the elements on which consumers focus their attention and how they explore any given stimuli. Many studies have used the eye-tracking (ET) technique to measure consumers’ visual attention and understand how they process an ad’s information and measure its effectiveness (Gómez-Carmona et al., 2022; Espigares-Jurado et al., 2020; Puskarevic et al., 2016). In this study, we are interested in how the elements of NPOs print advertisements act to capture the audience’s visual attention and promote or prevent donor behaviour. More specifically, we will study how donation behaviour and Aad could be modulated by the positive and negative emotional appeals of familiar and unfamiliar NPOs brands.

Brand awareness is important to marketers, especially in the non-profit sector, considering the increasing amount of NPOs providing aid to needy populations, particularly given the humanitarian crisis due to wars and/or geopolitical conflicts. The audience is exposed to many NPOs’ advertisements asking for donations. Therefore, it is crucial to identify the elements of the ad that are more effective for this sector. Consequently, it is essential to keep in mind that unfamiliar and familiar brands are different in terms of the knowledge the customer holds in their memory about the brand (Dogan et al., 2021).

This research aims to explore how the different elements of NPOs’ print advertisements may impact advertising effectiveness and to determine how brand familiarity (familiar and unfamiliar brands of NPOs) may modulate donor behaviour and Aad. Therefore, this paper is organized as follows: first, we discuss the concepts of visual attention and brand familiarity. Then, the research is carried out in two studies. Study 1 analyses advertising effectiveness, considering visual attention, Aad, and willingness to donate to unfamiliar NPOs. In Study 2, we examine ads of a familiar NPO. Finally, we present some conclusions, limitations, and future research.

2 Conceptual framework

2.1 Brand familiarity

There is extant work that demonstrates that branding can transmit the beliefs and values of a NPO to potential donors and show compelling reasons why it is worthy of support (Sargeant et al., 2008b). The organization’s image can provide some assurance to potential donors in terms of trust, efficiency, and level of familiarity (do Paço et al., 2014).

The concept of brand familiarity is associated with an individual’s knowledge about a non-profit brand. It is considered one of the main factors that impact willingness to donate (Ali et al., 2022; Dogan et al., 2021).

For NPOs, brand familiarity is crucial because usually, the audience does not have enough information about the services and products offered by organizations (Torres-Moraga et al., 2010). Thus, to evaluate and trust an organization, a familiar brand is probably the only sign supporters have (Rim et al., 2016). As brand familiarity comprises consumers’ information about the brand, exposure to a familiar brand might reduce the time taken to process brand information and, consequently, the time to make a decision (Ha et al., 2022).

Previous research has evaluated the effect of brand familiarity on donation behaviour. A study showed that supporters only donated when the NPO was familiar (Casais & Santos, 2018). Dogan et al. (2021) investigated the relationship between brand familiarity and donation behaviour, finding a direct positive relationship between the two variables.

2.2 Visual attention

Attention is defined as the capacity to focus on some elements of the environment while ignoring others (Venkatraman et al., 2015). Two perspectives of selective visual attention explain where we focus attention: bottom-up factors, in which stimulus elements (such as colour, size, shape, orientation) attract attention and processing; and top-down factors, in which attention depends on the task because subjects will focus on the most relevant information to achieve their goal (Itti & Koch, 2001). Visual attention is determined by the interaction of both perspectives (Onișor & Ioniță, 2021).

When the information is received passively, bottom-up attention prevails. Thus, during incidental exposures, the ads’ influence is unconscious (Berger et al., 2012). Such an attention process can be measured using an implicit technique that is non-intrusive, such as the eye tracker. Visual attention can be monitored through eye movements, so eye trackers can monitor visual attention by recording patterns of fixations and saccades that emerge across a visual field. This technique allows us to obtain the unconscious responses to the ad and a moment-to-moment assessment of these responses (Casado-Aranda et al., 2020).

Previous research has supported using ET to analyse advertising effectiveness (Gómez-Carmona et al., 2022; Martinez-Levy et al., 2021; Sciulli et al., 2017). Bebko et al. (2014) conducted a study using ET to analyse the impact of advertising appeals on donor behaviour, finding that NPOs’ ads should encourage viewers to look at the face in the ads because the more time spent and the more times they look at the face, the greater the possibility of recommending others to donate. Another study analysed print ads using ET, measuring how the size of the three key ad elements (pictorial, brand, and text) captured participants’ attention to the ads. The results showed that the pictorial elements attracted the most attention regardless of their size (Pieters & Wedel, 2004).

In this research, we marked as Area of Interest (AOI) the three main elements (text, image, logo) to obtain the ET metrics. From the several metrics that might be obtained by using ET, the ones analysed in this research are:

-

Time to First Fixation (TTFF): refers to the time, in seconds, for a participant to first look at a specific AOI.

-

Number of Fixations (nFix): indicates the number of times the participant makes a short stop in the AOI.

-

Time in AOI: refers to the time the participant spends exploring the AOI.

3 Objectives

The purpose of this research is to explore how the different elements (image, text, logo) of NPOs’ print ads with different emotional appeals (positive and negative) influence donation behaviour and the Aad, applying ET metrics such as time in AOI, nFix, and TTFF. Although previous studies have explored these metrics in NPOs’ ads, this investigation further considers possible differences between familiar and unfamiliar NPOs.

4 Hypotheses

As mentioned, brand familiarity can facilitate deciding, because it helps reduce the time to process information. The research found that when evaluating a familiar brand, less cognitive effort is used, and participants tend to have a more favourable opinion than when using an unfamiliar brand (Tam, 2008). Therefore, it is believed that there is a stronger relationship between purchase intention and customer satisfaction with familiar brands (Das, 2015). Also, it has been found that NPOs’ fame and impression positively impact donor behaviour (Sargeant et al., 2008a, b).

NPOs’ ads generally employ emotional appeals, as the emotions evoked by an ad have been shown to influence attitude (Xu, 2021; Choi et al., 2020). Also, recent research has found a significant relationship between the effectiveness of social cause advertising and Aad because “attitude is a driver for behaviour” (Hamelin et al., 2017, p. 104).

Previous research has found a relationship between the frequency and duration of fixations and donation behaviour (Alonso Dos Santos et al., 2017; Sciulli & Bebko, 2005). According to Bebko et al. (2014), there is a significant relationship between the AOI of the face and the TTFF, which means that when the emotion becomes more positive, the TTFF in the AOI of the face increases. In addition, the authors found positive correlations between fixation counts and total visit duration with the intention to recommend others to donate.

Hence, we propose the following hypotheses:

-

H1. The measurement of the visual attention on the elements of print ads (text, image, logo) using positive and negative emotional appeals has a relationship with donation behaviour for both familiar and unfamiliar NPOs.

-

H2. The measurement of the visual attention on the elements of print ads (text, image, logo) using positive and negative emotional appeals has a relationship with the Aad for both familiar and unfamiliar NPOs.

-

H3. There is a relationship between Aad and the donation behaviour of ads using positive and negative emotional appeals for both familiar and unfamiliar NPOs.

-

H4. For both types of NPOs (familiar and unfamiliar), there will be differences between the ET metrics (TTFF, Time in the AOI, and nFix) of each AOI and the ad’s frame (positive or negative).

-

H5: There are differences in the Aad between familiar and unfamiliar NPOs.

-

H6. There are differences in the visual attention metrics (TTFF and Time in AOI) of the logo area between the two types of NPOs (familiar and unfamiliar).

5 Methodology

To test the hypotheses, we conducted two studies, one with unfamiliar NPOs and the other with a familiar NPO. In both studies, we applied a questionnaire and the ET technique.

5.1 Study 1 sample and pre-test

The study was conducted with a sample of 72 participants (36 women, 36 men) with a mean age of 22.3 and a standard deviation of 2.8 years. The stimuli were selected by applying a pre-test to a sample of 105 individuals who evaluated 60 images of children (30 positive and 30 negative) and rated each image on a 7-point Likert scale, considering their perception of the child´s well-being. Images of children were chosen because they are powerful in generating an emotional response, which is why the selected organizations work for children (Burt & Strongman, 2005). Based on the pre-test results, we selected 14 pairs of images that scored highest for positive and lowest for negative emotional valence and selected 14 unfamiliar NPOs. The positive ads featured happy children expressing gratitude for the positive impact of donations on their lives. The negative ads featured distraught children facing health or poverty, warning that without donations, their lives were in danger.

5.2 Study 2 sample and pre-test

Sixty participants (30 women, 30 men) with a mean age of 28.3 and a standard deviation of 4.7 years participated in this study. To select the stimuli and the most familiar NPO, a pre-test was conducted on 64 individuals with a mean age of 33.4 years and a standard deviation of 7.1 years who evaluated the valence of 19 pairs of images on a 7-point Likert scale. The images selected for study 2 were of children as in study 1. Then, we selected the 10 pairs of images that scored highest for positive and lowest for negative emotional valence. In this study, UNICEF was selected as the most familiar NPO of humanitarian aid, as it was known by 92.2% of the pre-test sample.

5.3 Data collection

The studies were carried out similarly. They were conducted in a neuromarketing lab environment. Participants were asked to sit at a desk with a screen on which the stimuli were presented. The screen measured 21 inches diagonally and had a 1920 × 1080 pixel resolution, and the stationary ET device was attached to it. The ET used in both studies was a Tobii X2-30 Compact Edition, which captures gaze data at 60 Hz.

All participants were asked to sign an informed consent before the experiment and received monetary retribution for their participation. During the experimentation phase, the ET was calibrated, and the participant was asked to look at several points on the screen to ensure the accuracy of the results.

In Study 1 (unfamiliar NPOs), the participants were divided into two groups to present the randomized stimuli individually for 6 s for each image. The stimuli developed for this study were presented to the participants, and each group viewed either the positively framed ad or the negatively framed ad for each NPO. After the presentation of the stimuli, they answered a questionnaire to collect their demographic data, their Aad (using a 7-point semantic differential scale) (Holbrook & Batra, 1987), and their donation behaviour. As each participant was rewarded with 20€ at the beginning of the experiment, to measure their real donation behaviour, at the end of the experiment, they were asked if they wanted to donate a part or the whole amount of their reward. If they accepted, they had to write the amount and NPO to which they wished to donate.

In Study 2 (familiar NPO), a between-subject experiment was conducted. The participants were divided into two groups, one for the positively framed ads and the other for the negatively framed ads. The rest of the experiment was similar to Study 1.

6 Results

In this section, we present the result of both studies. First, the results of Study 1, where the NPOs were unfamiliar. We then show the results for the familiar brand. Finally, we present the result of the analyses combining both studies to test Hypotheses 5 and 6.

6.1 Study 1

The ET metrics allow us to examine the length of time it took a participant to look for the first time at the AOI (TTFF), the time it spent looking at the AOI (Time in AOI), and how many times it fixated on the AOI (nFIX in AOI). The metrics calculated the averages of the time, in seconds, and correlated them with the participant’s reply on the questionnaire to the Aad and their willingness to donate.

None of the ET metrics had a relationship with donation behaviour, so Hypothesis 1 was not supported for unfamiliar NPOs. On the other hand, the results showed a weak negative correlation between the Aad of negatively framed ads and the TTFF in the logo area of negatively framed ads (-0.261). The more positive the Aad, the less time it took to first fixate on the logo area. Also, there was a weak positive correlation between the Aad of negatively framed ads and the time spent in the image area of negatively framed ads (0.236). The more positive the Aad, the more time spent in the image area. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was partially supported for unfamiliar NPOs, as it was only supported for two of the ET metrics (time in AOI and TTFF) and only for negatively framed ads.

To test Hypothesis 3 for unfamiliar NPOs, we conducted a correlation analysis to examine the relationship between the Aad and donation behaviour. The results showed a positive effect between these two variables but only for negatively framed ads (r = 0.287), such that the more positive the Aad, the higher the willingness to donate. Hence, Hypothesis 3 was partially supported in the context of unfamiliar NPOs.

In Table 1, we can observe the results of a paired t-test analysis to test Hypothesis 4, which examines the differences between the ET metrics on the AOI and the ad’s frame. The results showed that for Group 1, there were differences in the nFix in the text area (t(35)=-3.416, p = 0.002) between positive and negative ads, with a higher nFix in negatively framed ads (1.83). Also, the TTFF (t(35) = 2.121, p = 0.041) and the time spent in the text area (t(35)=-5.022, p = 0.000) were higher for negatively framed ads. In Group 2, we observed differences in the nFix of the image area, with a greater nFix in the positively framed ads (3.93). Likewise, the time spent in the image (t(35) = 3.256, p = 0.003) and text (t(34) = 2.518, p = 0.017) areas was greater in positively framed ads. Hence, Hypothesis 4 was partially supported.

6.2 Study 2

When analysing the relationship of the ET metrics for the familiar NPO, in this case, UNICEF, and the donation behaviour considering the emotional appeal of the ad, we found no significant relationship between the variables. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was not supported in the context of the familiar NPO.

When the variables were analysed globally without considering the appeal, as shown in Table 2, a negative correlation was observed between donation and the TTFF in the logo area (-0.268), meaning that the less time it took to first fixate on the logo area, the participants chose to donate more.

On the other hand, the Aad showed a moderate negative correlation with the TTFF in the image area (-0.38) for negatively framed ads and with the TTFF in the text area (-0.56) for the positively framed ads, partially supporting Hypothesis 2.

Furthermore, in the global analysis, as shown in Table 2, the TTFF in the image (-0.62) and text area (-0.38) had a negative relationship with the Aad; that is, the more time it took to fixate on the image and the text area, the less positive the Aad. Additionally, the TTFF had a positive relationship with the TTFF on the logo area (0.56), indicating that the longer it took to first fixate on the logo area, the more positive the Aad, along with the nFix on the image area, which had a negative correlation with the image area (-0.42) and a positive correlation with the text area (0.39). Thus, when the number of fixations on the image area of the ad increased, participants had a more negative Aad, but when the number of fixations on the text area increased, participants had a more positive Aad.

The Aad had a significant positive relationship with the donation behaviour but only for positively framed ads (r = 0.385); thus, the more positive the Aad, the more willingness to donate increased. Therefore Hypothesis 3 was partially supported.

We also carried out an independent t-test to analyse the differences between the ET metrics on the AOI by frame (see Table 3). The nFix on the text area showed differences (t(58)=-5.897, p < 0.000), presenting a greater nFix in the positively framed ads (4.86) and on the image area (t(58) = 4.636, p < 0.000), but with a greater nFix in the negatively framed ads. Additionally, there were differences in all three AOI (text, image, and logo) for TTFF, in which it took more time to first fixate on the AOI of the negatively framed ads on the text (t(56) = 4.635, p < 0.000) and image (t(58) = 8.141, p < 0.000) areas. However, for the logo area (t(48)=-7.984, p < 0.000), it took more time to first fixate on the AOI of the positively framed ads. There were no differences in the time spent in the AOI for any of the AOI. Thus for familiar NPOs, our Hypothesis 4 was partially supported.

6.3 Studies 1 and 2

After analysing the results of each type of NPO (familiar and unfamiliar), it is interesting to explore the differences between them. Therefore, we examined the differences in the Aad, and hypothesis testing showed differences only when the ad had a negative emotional appeal (t(100) = 3.170, p = 0.002), with the familiar brand (UNICEF) presenting a more negative Aad (M = 3.32, SD = 1.76) than the unfamiliar brands (M = 4.45, SD = 1.60). Thus, Hypothesis 5 was partially supported.

Regarding the differences in the ET metric on the logo area of the ads of both familiar and unfamiliar NPOs, the results indicate that there were only differences in the TTFF on the logo area of ads with a negative appeal (t(84) = 5.682, p < 0.000), with a longer time to first fixate on the logo area of the unfamiliar NPOs. Furthermore, there were differences in the time spent in the logo area for both appeals, positive (t(87) = 5.849, p < 0.000) and negative (t(84) = 4.073, p < 0.000). A longer time was spent in the logo area of the unfamiliar NPOs for both types of emotional appeals. There were no differences in the nFix on the logo area by type of NPO (see Table 4). Thus, Hypothesis 6 was partially supported.

7 Discussion

This research examined the differences in the ET metrics (TTFF, nFix, Time in AOI) considering the emotional appeal of NPOs ads and brand familiarity and analysed the effect of these metrics on Aad and donation behaviour. The findings of this research revealed the relationship between visual attention, Aad, and donation behaviour in the context of familiar and unfamiliar NPOs.

Results of the visual attention metrics using the ET technique identified that for unfamiliar NPOs, there is a relationship between the TTFF in the logo area and the time spent in the image area with the Aad, but only when the ad is framed negatively. The logo for an unfamiliar NPO should be able to capture viewers´ immediate attention to increase a positive Aad. On the other hand, in the case of familiar NPOs, specifically UNICEF, there is a relationship between the Aad and TTFF in the image area for negatively framed ads and in the text area when the ad is framed with a positive appeal. This means that for a familiar brand of NPO, the quicker individuals first fixate on the image area of a negatively framed ad, the higher the positive Aad, but when the ad is framed positively for a familiar brand, the quicker individuals fixate on the text area of the ad, the higher the positive Aad. Thus, positive emotional appeals help capture attention to the text area faster, which might be useful when the NPO wants the message to stand out. On the other hand, for unfamiliar brands, positive Aad increases when it takes less time to first fixate on the logo area and more time to fixate on the image area of negatively framed ads. Interestingly, when the results of the familiar brand (UNICEF) are analysed globally, there is a relationship between the TTFF in the logo area and willingness to donate to the cause. This result is inconsistent with a previous study by Bebko et al. (2014), which determined that the longer the participant looks at the logo, the greater the probability of recommending others to donate.

As mentioned in previous research, the Aad is associated with the effectiveness of the ads (Septianto & Tjiptono, 2019; Hamelin et al., 2017; Bagozzi et al., 1999), and also with the level of involvement with the ad. Moreover, it has a direct impact on purchase intention and actual behaviour (Ting & de Run, 2015). So, in the context of NPOs, it is important to analyse the relationship between the Aad and willingness to donate, considering the emotional appeal of the ad. The results showed that for unfamiliar NPOs, the Aad and willingness to donate were positively correlated only when the ad was framed negatively, so when Aad increased (it was more positive), willingness to donate increased. However, for the familiar NPO (UNICEF), the relationship was significant only when the ad was framed positively. This is an interesting result, as UNICEF is a well-known NPO, and participants might have a preconceived attitude towards the organization, so using negatively framed ads might affect the Aad. When analysing the differences in the Aad for both types of NPOs, the results showed a significant difference in the Aad of the negatively framed ads, with the familiar brand (UNICEF) having a more negative Aad (M = 3.32, SD = 1.76) than unfamiliar brands (M = 4.45, SD = 1.60). These results are interesting, showing that consumers evaluate familiar and unfamiliar NPOs ads differently, and are more severe with familiar brands that present negative ads.

Another contribution of this research is that, although we found differences in the time spent in the logo area of positive and negative ads between familiar and unfamiliar NPOs, the time spent in the AOI of unfamiliar NPOs had no significant relationship either with the Aad or the donation behaviour. Although, for unfamiliar brands, it would be essential to display the logo correctly to make sure it is clear and easy to see because people have no prior knowledge of the NPO and must collect information to form a concept about it.

7.1 Research implications

The basis of this research was that brand familiarity influences how audiences process visual attention to NPO ads using emotional appeals and how this may affect the Aad and donation behaviour. This suggests that visual attention may indicate advertising effectiveness, so ET metrics could help predict whether strong emotional appeals (negative or positive) increase willingness to donate and improve the Aad. Therefore, applying ET technology to advertising effectiveness research provides immediate unconscious responses to ads. This has significant managerial implications for marketers, as it will allow them to create more effective ads. The results showed that familiar NPO brands should use positive emotional appeals to increase the positive Aad, but to increase donation behaviour, negative emotional appeals are more effective. On the other hand, unfamiliar brands should use negative emotional appeals that increase the time spent in the image area and improve the Aad.

8 Conclusion

For NPOs to achieve their principal goal, which is to help others who are less fortunate, they must be able to effectively motivate donation behaviour, especially because individual donations are becoming one of their main sources of income. A common way for NPOs to promote their cause is to use emotional appeals in their advertising (Septianto & Tjiptono, 2019). Thus, it is important to understand the effect of using this advertising strategy, also taking into account the audience’s knowledge of the brand (brand familiarity) and how the different elements of the ads (image, text, and logo) influence the Aad and donation behaviour.

The principal contribution of this research is that there are differences in the visual attention of NPOs ads as a function of brand familiarity. Our results are consistent with previous studies in which familiarity decreases information-processing time (Ha et al., 2022; Rim et al., 2016). In addition, the audience does not respond equally in their Aad to familiar versus unfamiliar NPOs when emotional appeals vary. For unfamiliar NPOs, the use of negative appeals does not elicit a negative Aad, as in the case of familiar NPOs. This result is inconsistent with previous research, suggesting that subjects tend to make a more positive evaluation of a familiar brand than of an unfamiliar brand (Das, 2015). This incongruency could be due to the previous attitude toward the familiar brand.

These results can guide NPOs about when and what emotional appeal should be used to increase attention and donation behaviour. Negative appeals seem more effective to increase donation behaviour for both familiar and unfamiliar NPOs. Positively framed ads were more effective in eliciting a positive Aad for familiar NPOs, positively correlating with donation behaviour.

8.1 Limitations and future research

Like any other research, this one has some limitations that should be acknowledged. A frequent criticism of the application of neuroscience techniques to the study of consumer behaviour is the use of small sample sizes, which are thought to have low statistical power (Lin et al., 2017). Consumer neuroscience studies are nevertheless capable of yielding valuable insights even with small sample sizes, according to prior research (Alonso Dos Santos et al., 2017; Martinez-Levy et al., 2021). Our findings should be interpreted cautiously, and future research with larger sample sizes is needed to confirm or refute the hypotheses.

Exposure to ads was forced, as we asked participants to watch the advertisements presented. Considering that in the real world, we can decide whether we want to look at the ads displayed, it would be interesting to conduct another study in a more ecological environment and measure advertising avoidance. NPOs use different formats to display their ads. In this research, we analysed only print advertisements, so an analysis of other types of formats, such as videos, would expand this research. Another future research could be to analyse other variables that influence donation behaviour because, for example, the attitude toward a familiar NPO might influence willingness to donate.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

Ali, B. H., Elaref, N., & Yacout, O. M. (2022). The effect of charity brand experience on donors’ behavioral intentions: The mediating role of charity brand personality and donors’ satisfaction. International Review on Public and Non-Profit Marketing, 0123456789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-022-00356-0

Alonso Dos Santos, M., Lobos, C., Muñoz, N., Romero, D., & Sanhueza, R. (2017). The influence of image valence on the attention paid to charity advertising. Journal of Non-Profit and Public Sector Marketing, 29(3), 346–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2017.1326355

Bagozzi, R. P., Gopinath, M., & Nyer, P. U. (1999). The role of emotions in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27(2), 184–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070399272005

Bebko, C., Sciulli, L. M., & Bhagat, P. (2014). Using eye tracking to assess the impact of advertising appeals on donor behavior. Journal of Non-Profit and Public Sector Marketing, 26(4), 354–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2014.965073

Berger, S., Wagner, U., & Schwand, C. (2012). Assessing adverising effectiveness: The potential of goal-directed behavior. Psychology & Marketing, 29(6), 411–421. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar

Bilgin, Y., & Kethüda, Ö. (2022). Charity social media marketing and its influence on charity brand image, brand trust, and donation intention. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Non-profit Organizations, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00426-7

Burt, C., & Strongman, K. (2005). Use of images in charity advertising: Improving donations and compliance rates. International Journal of Organisational Behaviour, 8(8), 571–580.

Casado-Aranda, L. A., Sánchez-Fernández, J., & Ibáñez-Zapata, J. (2020). Evaluating communication effectiveness through eye tracking: benefits, state of the art, and unresolved questions. International Journal of Business Communication. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488419893746

Casais, B., & Santos, S. (2018). Corporate propensity for long-term donations to non-profit organisations: An exploratory study in Portugal. Social Sciences, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8010002

Choi, J., Li, Y. J., Rangan, P., Yin, B., & Singh, S. N. (2020). Opposites attract: Impact of background color on effectiveness of emotional charity appeals. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 37(3), 644–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2020.02.001

Conlin, R., & Bauer, S. (2022). Examining the impact of differing guilt advertising appeals among the Generation Z cohort. International Review on Public and Non-Profit Marketing, 19(2), 289–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-021-00304-4

Das, G. (2015). Linkages between self-congruity, brand familiarity, perceived quality and purchase intention: A study of fashion retail brands. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 6(3), 180–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2015.1032316

do Paço, A., Rodrigues, R. G., & Rodrigues, L. (2014). Branding in ngos – its influence on the intention to donate. Economics and Sociology, 7(3), 11–21. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2014/7-3/1

Dogan, A., Calik, E., & Calisir, F. (2021). Organizational factors affecting individuals to donate to NPOs in the turkish context. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 32(2), 303–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-020-00207-8

Espigares-Jurado, F., Muñoz-Leiva, F., Correia, M. B., Sousa, C. M. R., Ramos, C. M. Q., & Faísca, L. (2020). Visual attention to the main image of a hotel website based on its position, type of navigation and belonging to millennial generation: An eye tracking study. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 52, 1–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101906

Gómez-Carmona, D., Muñoz-Leiva, F., Paramio, A., Serrano-Domínguez, C., & Liébana-Cabanillas, F. (2022). Influencia de la apelación del mensaje en la atención. Un estudio de eye-tracking. Vivat Academia, 33–60. https://doi.org/10.15178/va.2022.155.e1381

Ha, Q. A., Pham, P. N. N., & Le, L. H. (2022). What facilitate people to do charity? The impact of brand anthropomorphism, brand familiarity and brand trust on charity support intention. International Review on Public and Non-Profit Marketing, 0123456789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-021-00331-1

Hamelin, N., Moujahid, O., & Thaichon, P. (2017). Emotion and advertising effectiveness: A novel facial expression analysis approach. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 36(August 2016), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.01.001

Hibbert, S. (2016). Charity communications: Shaping donor perceptions and giving. En The Routledge Companion to Philanthropy (pp. 102–116). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315740324-10/CHARITY-COMMUNICATIONS-SALLY-HIBBERT

Holbrook, M. B., & Batra, R. (1987). Assessing the role of emotions as mediators of consumer responses to advertising. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(3), 404. https://doi.org/10.1086/209123

Itti, L., & Koch, C. (2001). Computational modelling of visual attention. Neuroscience, 2(February), 1–11.

Li, M. R., & Yin, C. Y. (2022). Facial expressions of beneficiaries and donation intentions of potential donors: Effects of the number of beneficiaries in charity advertising. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 66(2555), 102915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.102915

Lin, M. J., Cross, S. N. N., Jones, W. J., & Childers, T. L. (2017). Applying EEG in consumer neuroscience. European Journal of Marketing, 52(1), 66–91. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-12-2016-0805

Martinez-Levy, A. C., Rossi, D., Cartocci, G., Mancini, M., Di Flumeri, G., Trettel, A., Babiloni, F., & Cherubino, P. (2021). Message framing, non–conscious perception and effectiveness in non–profit advertising. Contribution by neuromarketing research. International Review on Public and Non-Profit Marketing, 2, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-021-00289-0

Onișor, L., & Ioniță, D. (2021). How advertising avoidance affects visual attention and memory of advertisements. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 22(3), 656–674.

Pieters, R., & Wedel, M. (2004). Attention capture and transfer in advertising: Brand, pictorial, and text-size effects. Journal of Marketing, 68(2), 36–50.

Pieters, R., Wedel, M., & Batra, R. (2010). The stopping power of advertising: Measures and effects of visual complexity. Journal of Marketing, 74(5), 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.74.5.48

Puskarevic, I., Dimovski, V., Nedeljkovic, U., & Mozina, K. (2016). Eye tracking study of attention to print advertisements: Effects of typeface figuration. Journal of Eye Movement Research, 9(5). https://doi.org/10.16910/jemr.9.5.6

Rim, H., Yang, S. U., & Lee, J. (2016). Strategic partnerships with non-profits in corporate social responsibility (CSR): The mediating role of perceived altruism and organizational identification. Journal of Business Research, 69(9), 3213–3219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.02.035

Sargeant, A., Ford, J. B., & Hudson, J. (2008a). Charity brand personality: The relationship with giving behavior. Non-Profit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 37(3), 468–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764007310732

Sargeant, A., Hudson, J., & West, D. C. (2008b). Conceptualizing brand values in the charity sector: The relationship between sector, cause and organization. The Service Industries Journal, 28(5), 615–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642060801988142

Sciulli, L. M., & Bebko, C. (2005). Social cause versus profit oriented advertisements: An analysis of information content and emotional appeals. Journal of Promotion Management, 11(2–3), 17–37. https://doi.org/10.1300/J057v11n02

Sciulli, L. M., Bebko, C. P., & Bhagat, P. (2017). How emotional arousal and attitudes influence ad response: using eye tracking to gauge non-profit print advertisement effectiveness. Journal of Marketing Management, 5(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.15640/jmm.v5n1a1

Septianto, F., & Paramita, W. (2021). Sad but smiling? How the combination of happy victim images and sad message appeals increase prosocial behavior. Marketing Letters, 32(1), 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-020-09553-5

Septianto, F., & Tjiptono, F. (2019). The interactive effect of emotional appeals and past performance of a charity on the effectiveness of charitable advertising. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 50(April), 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.05.013

Septianto, F., Kemper, J. A., & Chiew, T. M. (2020). The interactive effects of emotions and numerical information in increasing consumer support to conservation efforts. Journal of Business Research, 110(February), 445–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.02.021

Tam, J. L. (2008). Brand familiarity: Its effects on satisfaction evaluations. Journal of Services Marketing, 22(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040810851914/FULL/XML

Ting, H., & de Run, E. C. (2015). Attitude towards advertising: A young generation cohort’s perspective. Asian Journal of Business Research. https://doi.org/10.14707/ajbr.150012

Torres-Moraga, E., Vásquez-Parraga, A. Z., & Barra, C. (2010). Antecedents of donor trust in an emerging charity sector: The role of reputation, familiarity, opportunism and communication. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 29 E, 159–177.

Venkatraman, V., Dimoka, A., Pavlou, P. A., Vo, K., Hampton, W., Bollinger, B., Hershfield, H. E., Ishihara, M., & Winer, R. S. (2015). Predicting advertising success beyond traditional measures: New insights from neurophysiological methods and market response modeling. Journal of Marketing Research, 52(4), 436–452. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.13.0593

Xu, J. (2021). The impact of guilt and shame in charity advertising: The role of self-construal. Journal of Philanthropy and Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.1709

Yousef, M., Dietrich, T., Rundle-Thiele, S., & Alhabash, S. (2022). Emotional appeals effectiveness in enhancing charity digital advertisements. Journal of Philanthropy and Marketing, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.1763

Zemack-Rugar, Y., & Klucarova-Travani, S. (2018). Should donation ads include happy victim images? The moderating role of regulatory focus. Marketing Letters, 29(4), 421–434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-018-9471-8

Zhang, Y., Lin, C., & Yang, J. (2019). Time or money? The influence of warm and competent appeals on donation intentions. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(22). https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226228

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Bit-Brain S.L. for their technological equipment, assistance, and support.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. This work was funded by grant RTC-2016-4718-7 from the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry, and Competitiveness. Also, by Community of Madrid, Spain under the Multiannual Agreement with the Complutense University of Madrid in the line Excellence Programme for university teaching staff, within the framework of the V PRICIT (V Regional Plan for Scientific Research and Technological Innovation). And the Marketing Department of the Complutense University of Madrid.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

García-Madariaga, J., Simón Sandoval, P. & Moya Burgos, I. How brand familiarity influences advertising effectiveness of non-profit organizations. Int Rev Public Nonprofit Mark (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-023-00380-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-023-00380-8