Abstract

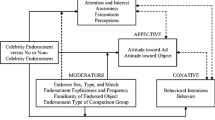

Our article examines market segments within the broader category of individual donors to charity and cause related organizations. This is an area of research in which considerable conflicting results have been produced. In our study, we find that while similarities between these segments exist along demographic factors and donation behaviour (e.g., frequency of donating), important distinctions exist along motivational factors, thereby suggesting differentiated promotion messaging. Surveys were administered to 680 subjects. Their responses along twenty-seven motivational variables were subjected to factor analysis. Cluster analysis was then applied to the factor scores that yielded three donor segments. We find six key motivating factors influencing the donation decision: organizational criteria, external inducements, intrinsic motivators, charity organization attributes, egocentric rewards and economic considerations. We also find three distinct segments of individual donors: intrinsics, sceptics and impressionable. Donations by the intrinsic group members are more influenced by selfless altruistic reasons for donating. Decisions made by members of the skeptic segment result from the examination of charitable organization along such criteria as the clarity of its mission and the efficiency of its management practice. The impressionable segment members are most likely to be influenced by the impact of external factors in the donation decision such as marketing measures employed by the charity and the encouragement of others.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Nonprofit organizations face the increasingly complex challenge of attracting adequate funding from individual donors who are presented with many options for contributing to charities and causes, often with limited funds. Consequently, like product organizations in the private sector, it has become more and more necessary for nonprofit organizations to adopt marketing practices in order to compete for contributions (Besana & Annamaria, 2019; Kemp et al., 2013; de Vries et al., 2015; Hoye, 2007). Here, some researchers suggest that charitable organizations in particular must go beyond a limited interpretation of the marketing orientation in which a company focuses merely on meeting the needs of customers and investors. Instead, they suggest that this perspective must be expanded upon with a societal orientation in which the needs of multiple stakeholder groups are met, including addressing vital social causes (Sargeant et al., 2002; Shemyatikhina et al., 2020; Sujo et al., 2020).

Despite this complexity in applying marketing practice to the nonprofit sector, a key element of the discipline must be included in planning and implementation. That is, at the most fundamental level, charitable organizations must thoroughly identify and analyze donor market segments rather than view them as a homogenous group (Hou et al., 2014; Terech, 2018). Consequently a growing yet far from conclusive body of research has been conducted in which the similarities and distinctions between multiple possible donor segments have been examined along such areas as socio-demographic and behavioral bases.

Focused messaging that appeals to the desires of each segment is a crucial component of such a targeted strategic marketing approach (Kemp et al., 2013; Hou et al., 2014). Additionally, due to their philanthropic nature, charitable organizations have limited funds to begin with, particularly for marketing research and administrative costs (de Vries et al, 2015). Therefore, multiple segmentation provides an essential benefit of conserving funds in that this approach reduces the risk of wasting resources on unfocused and therefore ineffective advertising efforts (Mainwaring & Skinner, 2009). Moreover, de Vries et al. (2015) point out that there is a substantial segment of consumers in the donor market who are particularly likely to disapprove of wasteful spending by charitable organizations. In a similar vein, a study conducted by Gneezy et al. (2014) found that donations rose significantly as perceptions of a charitable organization's aversion to overhead expenses increased.

2 Objectives and contributions

This study intends to extend the literature by identifying comprehensive profiles of segments within a broader market of individual donors to charitable and causal organizations along with differentiated marketing approaches for targeting each of them. Although a considerable amount of research does exist on this topic, some of the results about segment profiles within the market of charitable contributors are conflicting along demographic, psychographic and other segmentation criteria. It would appear that what makes a difference between donor groups is not external (e.g., demographics) but who they are internally, and what produces their behavior. This paper follows on research by de Vries et al. (2015), Heiser (2006) and Dolnicar and Randle (2007) recommending data driven post hoc research in which the bases or criteria for grouping contributors are not presumed or guessed using an a priori approach. We attempt to objectively arrive at distinct segments by taking into account an entire set of information. In meeting this recommendation, our study examines individual donors along several areas, including socio-economic, behavioral, and, in particular, motivational factors. Furthermore, Shields (2009), suggests that the heterogeneity of motivational factors is a particular issue that needs to be examined as a criteria for segmenting contributors to charities, and this area is explored extensively in our paper.

This research also offers practical benefits by comparing subsets of donors on the basis of their expectations of a charity’s marketing mix offerings to donors, including its distribution and promotional elements. We also offer suggested marketing program approaches aimed at different donor groups. Also, from a promotion standpoint, this paper addresses the recommendation offered by Garber and Muscarella (2000) to examine the burgeoning area of digital media as a marketing channel for targeting the stakeholders of nonprofit organizations (Smith, 2018; Yoo & Drumwright, 2018). Here, we compare and contrast consumer preferences regarding various general promotional outlets and social media platforms specifically among segments of individual donors.

3 Literature review

We provide an extensive review of research on market segmentation of individual donors to charitable organizations. Here we will focus on the approaches commonly addressed in the literature, namely segmentation on the bases of demographic characteristics, donation behavior, motivators, and donor interests (preferred types of charities or causes).

3.1 Demographic segmentation

Sargeant and Ewing (2001) as well as Randle and Dolnicar (2009) note that demographic factors have been reported as significant predictors of “heavy” charitable giving. In general, the research, although revealing some commonalities, also points to conflicting results along several socio-economic variables as predictors of donating.

Some studies produced common results regarding the impact of age and gender on donation behavior. Kohlberg (1975) suggests that age correlates positively with the level of charitable contributions because people go through a developmental process in which they progress from being egoistic to having progressively greater levels of concern for others. Heiser (2006) also reports on a positive association between age and charitable-giving. Additionally, Durango-Cohen et al. (2013) note that many past studies report that differences in donation behavior can be explained by various demographic factors, including age and gender. Kemp et al. (2013) found distinctions in certain traits between men and women imposed by society, namely regarding feelings of sympathy and pride, with consequent differences between them regarding the charitable appeals to which they tend to respond. These researchers conclude that women, being more driven by sympathy than pride, tend to be inclined to donate for social change, whereas men, more driven by pride, tend to give to charities and causes that enable them to gain more prestige.

However, contrasting findings regarding the impact of age and gender have also been revealed by other research. For example, Johnson et al. (2014) in a study conducted in a southeastern U.S. city, found no difference in gender or age regarding respondents’ willingness to donate to a performing arts organization. Similarly, Heiser (2006) reported mixed support for a significant relationship between gender differences and charitable-giving behavior. Adding to these discrepancies in the literature, Randal and Dolnicar (2009) reported no significant differences between levels of volunteering activities (i.e., high contribution volunteers vs low-contribution volunteers) in relation to gender. These inconsistencies suggest that while socio economic variables are generally good descriptors of consumer segments in general (Royne Stafford & Tripp, 2000), the development of comprehensive profiles of any consumer groups, including that of individual donors, requires that segmentation analysis be enriched with other factors (Clopton et al., 2006; Colbert, 2014).

3.2 Behavioral segmentation

A branch of segmentation research has focused on using purchase (i.e., contribution) results to find patterns in this data regarding relationship perceptions and to predict future charitable donations (e.g., Durango-Cohen & Balasubramanian, 2015; Johnson et al., 2014). For example, Johnson et al. (2014) and Taylor and Miller-Sevens (2019) found that donors’ perceptions of a strong relationship with a causal organization lead to a greater willingness to contribute. Durango-Cohen et al. (2013) also acknowledge the considerable extent to which research on donor segmentation has focused on behavioral data, specifically the recency, frequency and monetary value of contributions (or RFM statistics) in which individuals sharing similar RFM characteristics are grouped into segments for better predicting future donation behavior. Durango explains that this segmentation method is based on the argument that the best predictor of future donor behavior is past behavior, so those with similar RFM statistics should be grouped together. Aggarwal (2002) and Johnson and Grimm (2010) find that the willingness to contribute increases as the relationship between contributor and organization progresses from the mere bestowal of a donation to that of a more communal relationship in which the contributor develops a stronger emotional bond with the organization.

However, Durango-Cohen et al. (2013) notes that reliance on RFM statistics alone introduces an aggregation bias that masks the underlying motivational factors that trigger behavior. Similarly, Johnson et al. (2014) conclude that donor behavior patterns, particularly regarding the intensity of the relationship between the donor and the charitable organization, were found to be ineffective predictors of the individual’s willingness to donate. In this regard, Dolnicar and Randle (2007) suggest that motivation-based data must accompany mere RFM statistics in order to better understand the nature of the homogeneity within donor segments as well as the differences between them, thereby allowing nonprofit organizations to more effectively target each donor group with customized messaging. Thus, predictive models of donation behavior that account for motivational factors that trigger donation behavior are necessary for a more comprehensive understanding of donor segments.

3.3 Motivation based segmentation

A considerable volume of research attributes segmentation on the basis of donor motivations as an efficient means of differentially targeting contributors in an effective and efficient manner, (e.g., Shields, 2009). Motivators can be generally subdivided into altruistic, and egocentric categories. Heiser (2006) notes that either set of motivations are a function of the individual’s adoption of norms, that is, behavioral expectations one finds in a social setting. The individual is confronted with social normative influences such as product brands and even cues involving donation appeals and such inducements must be reconciled with the personal moral norms that define one’s value system. In the case of marketing a charitable cause, value systems form a basis for segmentation that inform the development of promotional appeals that can be differentially directed to different groups in accordance with their respective sets of moral norms.

Altruistic motivations involve a desire for prosocial behavior (Bachke et al., 2014; Heiser, 2006; Saito, 2015). That is, an individual’s desire to contribute is based on an intrinsic desire to help others (Shields, 2009) and, moreover, to contribute to the betterment of one’s community. Egoistic motives for charitable contributions are concerned with the desire to enhance one’s internal sense of wellbeing by receiving material and or emotional benefits in return for making a donation (Bennett, 2006). Egoistic motivations may be divided into utilitarian, emotional and social benefits. Utilitarian benefits, also referred to as mercenarily oriented motivations, involve the desire for material benefits in exchange for a contribution, such as tax benefits, educational benefits derived from volunteering activities that provide career enhancement (Demir et al., 2020; Randle & Dolnicar, 2009) and objects of recognition (e.g., plaques, naming opportunities, etc.). The compensation desired in exchange for contributions also apply to emotional benefits such as a “feel good” emotion (alternatively known as “warm glow” or “helper’s high”), a reduction of guilt feelings, receiving an expression of appreciation from the charitable organization (e.g., a simple “thank you”), and the fulfillment of attachment (or care giving) desires (Bachke et al., 2014; Andreoni & Petrie, 2004).

In contrast to prosocial motivations which are altruistic or other-oriented in nature, several researchers suggest that what externally may appear as benefits to society can also involve purely egoistic reasons for contributing (e.g., Clary et al., 1998; Omoto & Snyder, 1995). Randle and Dolnicar (2009) describe such reasons as being able to meet different types of people, “being able to socialize with people like me,” and simply the opportunity to socialize in general. In addition to these desires, social reasons also involve the appeal of elevating one’s social class or status (Andreoni & Petrie, 2004; Sargeant & Ewing, 2001). In terms of the magnitude of donations, Boenigk and Scherhag (2014) found that such egoistic social motivations correlated with higher levels of contribution activity than those of a utilitarian (material) nature. Furthermore, in comparing a sample of low and higher contributor groups, Randle and Dolnicar (2009) found those having the egoistic desire to socialize applied more to high contributors than was the case even for those primarily motivated to donate for altruistic reasons.

Heiser (2006) explains that moral norms in general are developmental rather than static. Moreover, motivations arising from moral norms exist along a continuum ranging from being entirely egoistic to developing increasingly greater levels of altruism (i.e., concern for the welfare of others). This research further concludes that one’s attainment of higher levels of altruism, i.e., to becoming more idealistic and fairness driven, leads to a greater likelihood for charitable giving. However, this finding appears to conflict with the research of Hou et al. (2014) who conclude that although one may be intrinsically motivated to give for selfless reasons, most donations are actually made in response to some form of solicitation in which an individual may have the expectation of receiving a benefit in exchange for a contribution. These contrasting findings suggests that altruism is not necessarily devoid of egoistic motivations. For example, Dolnicar and Randle (2007) and Shields (2009) point out that altruistic actions are primarily based on a desire to help others and are seldom accompanied by the desire for tangible benefits in return. However, altruistic behavior can be egoistic in the sense that the contributor may seek the aforementioned positive feelings that accompany the act of giving such as “warm glow” emotions (Andreoni, 1990; Bachke et al., 2014) time after time.

3.4 Donor interests

A branch of the literature also examines segmentation based on the types of charities or causes to which individual donors are drawn (e.g., Hou et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2017). According to Hou et al. (2014) and Taylor and Miller-Stevens (2019), the appropriateness of this method of segmentation is based on social identify theory in which individuals find a greater sense of self and personal satisfaction by affiliating with organizations with which they personally identify.

This means of segmentation suggests practical marketing approaches for expanding individual donations. An organization involved in a particular charity or causal area should seek out the segment of donors who are most likely to identify with its mission. For example a charity involved with animal rights might target veterinarians and pet owners. Upon identifying targeted segments in this manner, the charity must then seek to differentiate itself, particularly from similar types of organizations. Hou et al. (2014) found that such competitive measures undertaken by the charity to differentiate itself increase the ability of individuals to identify with the organization, thereby positively impacting donation intentions and behaviors. Differentiation can be achieved through a variety of marketing measures such as distinctive messaging and branding. However, while it is necessary to create a distinct identify, facilitating the target market’s identification with the organization should remain the primary focus. This should extend to the employment of sensory language in advertising messaging (both verbal and nonverbal) that the target market can personally relate to and identify with (Mainwaring & Skinner, 2009).

4 Method

We combined the data sets of two marketing research investigations. The research instruments were two sets of formal surveys distributed over a six month period to residents in the San Francisco Bay Area. One set of surveys was personally administered while the other (submitted months later), was emailed due to restrictions caused by Covid-19. The data, drawn from common questions in the two sets of surveys, was consolidated, allowing for an adequate sample size of current and potential donors to charitable and cause related organizations. The surveys were an element of marketing research investigations to respectively assist two small nonprofit organizations devoted to child related causes. Each group of surveys was finalized after pretesting the instruments with 10 subjects. Prior to its completion and administration, we also submitted the surveys to the Executive Director of each organization in order to ensure for clarity and completeness of the research instruments.

A combination of convenience and judgement sampling was applied for the surveys. In the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, the e-mailed surveys were administered to San Francisco Bay Area residents through social media groups (e.g., Nextdoor and Facebook). A survey was deemed as completed if the respondent answered all of the questions.

A key question, posed in both research instruments, asked respondents to rate the importance of 27 variables in motivating them to make a financial contribution to a nonprofit organization involved in a charity or cause. Responses were answered on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from (1) “Not at all important” to (5)” Extremely important.” These variables included personal motivators, such as the having a personal connection with the charity or cause and personal gratification by contributing. Variables pertaining to desired organizational criteria for warranting contributions from the individual donor were also examined such as a clear and compelling mission statement and its trustworthy reputation. In addition, the importance of various marketing measures were addressed such as gift incentives resulting from donations and the convenience of the donation method offered by the nonprofit organization.

The motivators in the survey were derived from three sources. First, was the authors’ extensive experience in conducting marketing research for a variety of nonprofit organizations in which similar survey instruments were constructed and refined. Second, the review of secondary research reflected in the literature review was an important source in arriving at the 27 motivational variables.

We applied principal components analysis to all 680 subjects on data drawn from the motivators question for the purpose of arriving at a smaller and therefore more manageable number of statistically independent variables. Next, k-means cluster analysis was applied to respondents’ factor scores for arriving at distinct segments of respondents.

The clusters of individual donor subjects were then profiled and compared along mean responses to each of the 27 motivational variables across the factor categories. Profiles of the subsegments were further enriched and compared on the basis of demographic variables, their preferred sources of information about charity and/or causal organizations (including social media options), their frequency of donating to child related nonprofit organizations and their behavioral intentions of donating in terms of the likelihood that they would make a donation to a child related charity or causal organization in the near future. Along these variables, cross-tabulation for nominal data and one-way ANOVA for ordinal and interval data were used to test for significant differences between the segments. Additionally, cross tabulation was used to examine the clusters on the basis of the types of charities to which they were drawn. Here, respondents were asked to rank the three types of charities/causes they were most compelled to support from a list of 13 options. These included child, environmental and poverty related causes.

5 Data analysis results

5.1 Factor analysis interpretation

We performed factor analysis on the 27 motivational variables using principal components extraction with varimax rotation. This process resulted in 7 factors with eigenvalues above 1, accounting for approximately 58.2% of the total variance in the data (Table 1). Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant at a 0.0000 level, indicating that factor analysis was an appropriate data reduction method for the 27 variables.

The seven factors were named and interpreted as follows.

Factor 1: organizational criteria The importance of several variables converged on this factor and are associated with criteria upon which the organization is judged by the individual making the donation decision, i.e., a clear and compelling mission statement, the organization’s trustworthy reputation, efficient organizational management, having awareness of the organization’s cause, knowing how donation funds are used, hearing a clear and compelling story about a charity or cause, and seeing evidence of the organization’s effectiveness.

Factor 2: external inducements The commonalities of the motivators loading highly on this factor relate to specific external marketing measures that may encourage the decision to donate. These include sales promotion activities such as offering gift incentives to donors, the utilization of an influential spokesperson, and gift matching arrangements. These measures also include the convenience of the donation method which relate to the distribution aspect of marketing to donors. Hou et al. (2014), contend that although donations can be intrinsically motivated, most donations are made in response to these external forms of solicitation. However, these marketing activities are methods not limited to customer (or, in this case, donor) acquisition in which an initial exchange is sought between the organization with the donor. Specifically, results of the study conducted by Bennett (2006) show that manifestations of appreciation by the charitable organization through such means as gifts and being thanked for donations are conducive to building a communal relationship between the donor and the organization. Likewise, Bennett (2006) notes that relationships can be enhanced by providing a wide variety of donation methods as this results in multiple points of contact in which the donor can become more familiar with the organization.

Factor 3: intrinsic motivators Variables loading on this factor, i.e., having a personal connection with the charity or cause, one’s personal interest in the charity or cause and the desire to contribute to the well-being of one’s community are associated with what Hou et al. (2014) term intrinsic motivations associated with one’s values or world view. Further, Heiser (2006) suggests intrinsic rewards such as one’s desire to contribute to the wellbeing of the community are associated with the individual’s moral norms of idealism and fairness in which the individual has evolved from egoism to having a concern for the welfare of others.

Factor 4: organization attributes The criticality of the organization’s financial need, its wide spread reputation and the fact that it may be in the same geographical locale as that of the donor can be regarded as organizational circumstances or attributes that could motivate contributions.

Factor 5: social influences The variables that converge on this factor, i.e., the influence of others and the fulfillment of a religious obligation are variables that clearly relate to the social influences upon the individual’s decision in making charitable contributions. The influence of others (e.g., family and friends) is related to reference group influence upon the contributor. This factor also encompasses the social impact manifested by the perceived effectiveness of charitable organization’s promotional efforts exerted upon the individual’s donation behavior.

Factor 6: egoistic rewards The motivators of gaining personal recognition and personal gratification by contributing, as well as feelings of sympathy about a charity and cause are motivators that Bennett (2006) associates with egoistic rewards experienced by making donations. Smith et al. (1989) refer to such motivations as “helpers high” or the pleasurable emotional experiences by making a charitable contribution because doing so makes donors feel good about themselves.

Factor 7: economic considerations The variables dealing with the importance of obtaining a tax write-off and one’s financial ability to donate clearly relate to economic considerations that impact donation behavior. These motivators fall under the category of what Bennett (2006) and Johnson et al. (2014) suggest are mercenary or utilitarian reasons for making donations.

5.2 Cluster analysis

We applied k-means cluster analysis to respondents’ factor scores among the 680 formal survey respondents and compared intergroup means along the 27 motivational variables presented in Table 2. Through a process combining statistical fit and managerial relevance, both three cluster and two cluster operations were run. Both operations revealed several distinct differences between paired cluster groups along the 27 motivator variables encompassing the seven factors. It was decided that grouping these subjects into three clusters rather than two would prevent under-stratification of the sample and yield more comprehensive suggestions for addressing the distinct expectations between subsegments of individual donors.

As shown in Table 3, there were no significant differences between the three segments regarding the average frequency of donating to a child related charity or cause over the most recent three-year period. Over the most recent 3 years, each segment had contributed between 1.26 and 1.52 times. Likewise, in terms of purchase (or in this case, donation) intentions, no significant intergroup differences occurred between the three segments regarding the likelihood of beginning or increasing donations to a child related charity. The overall mean across the three clusters was 2.80, i.e., between “”not very likely” and “”somewhat likely” (Table 4).

5.2.1 Motivators

As shown in Table 2, ANOVA analyses suggests commonalities and key intergroup differences between the overall profiles of the three groups. As far as intergroup similarities, knowledge and awareness of the charity or cause, and one’s personal financial ability to donate were ranked in the top five by all three segments among all 27 motivators examined. The organization’s trustworthy reputation also ranked high in importance among all three groups, i.e., first for Segment 2 and 6th and 2nd respectively for Segments 1 and 3. This finding is consistent with the study of de Vries et al. (2015) who find that trust and confidence in the organization is a key determinant of the donation decision process.

However, key distinctions between group profiles were also apparent, particularly in those cases in which one segment ranked the importance of a specific motivator the highest among the three groups and significantly higher in comparison to at least one of the other two groups;

The intrinsic variables making up factor 3 motivators were ranked highest by Segment 1 members. In this regard, contributing to the wellbeing of one’s community was the number one ranked motivator overall by this group and with a mean importance that was significantly higher than that of the other two groups. Likewise, the mean importance of having a personal connection with the charity or cause and having a personal interest in the charity or cause were rated significantly higher by Segment 1 than by the other two segments. In addition to these more philanthropic inducements, two of the three egoistic motivators, i.e., personal gratification by motivating and feeling sympathy about the charity/cause were ranked appreciably higher by Segment 1 and with significantly higher mean importance ratings compared to the other two groups.

It is also noteworthy that Segment 1 rated the importance of knowing how donations will be used by the organization significantly lower in importance than Segments 2 and 3. The intrinsic motives of this group are in contrast with those involving consumption motives for products and services in which the buyer seeks to make a purchase in exchange for something of equal value in return Johnson et al. (2014) However, according to Hou et al. (2014), charitable behaviors are often more motivated by the potential for psychological and social benefits such as the motivators of Factor 6. On balance, because of their seemingly more unconditional personal attraction overall to donating to charities and causes for primarily philanthropic reasons, but acknowledging that they also do so for egoistic purposes, members of Segment 1 will hereafter be referred to as the intrinsic segment (or “intrinsics”). This segment seems to be similar to the category of donors that Supphellen and Neslon (2001) refer to as the internalist, a group that responds positively to the donation decision based on internalized norms and values without being inclined to analyze the charitable organization nor the cause it represents.

The subjects of Segment 2 were distinctive along four of the six organization criteria motivators of Factor 1. In comparison to the two other groups, Segment 2 produced higher mean importance assessments for the charitable organization’s trustworthy reputation, knowing how donations are used by the organization, having knowledge and awareness of the organization, and evidence of the organization’s effectiveness. Segment 2 also rated the importance of the organization’s trustworthy reputation significantly higher than both of the other two groups and knowing how donated funds would be used significantly higher than segment 1. The nature of this segment appears to parallel the category of donors termed by Supphellen and Neslon (2001) as analysts, a category of contributors who carefully evaluate the organization soliciting the donation and the cause behind it. Because this group clearly stands out in terms of being circumspect about making the donation decision, this group will be referred to hereafter as the skeptical segment (or “skeptics”).

Among the organizational criteria variables of Factor 1, Segment 3 produced the highest importance rankings among the three groups for the inducements of a charitable organization’s clear and compelling mission statement, an efficiently managed organization and hearing a compelling story about a charity or cause. Among these three variables, Segment 3 ranked a clear and compelling mission statement and effective management significantly higher (at a 0.01 level) than did Segment 1.

Particularly noteworthy is the fact that Segment 3 ranked all six variables encompassing the extrinsic motivators of Factor 2 higher than the other two segments. Again, these items include a show of appreciation for the donation as well as the marketing inducements of utilizing an influential spokesperson, gift incentives, a donation schedule and offering convenient methods of making donation. Moreover, the mean importance ratings of all of these variables were rated significantly higher by Segment 3 than by each of the other two groups. Johnson et al. (2014) suggest that such donors are relatively more desirous of entering into an exchange relationship with the causal organization in which the individual gives to the organization because they want something comparable in return. However, as suggested by Hou et al. (2014), charitable behaviors are often more motivated by the potential for obtaining psychological and social benefits rather than material rewards. What is also observed to be distinctive among Segment 3 members is the higher importance attached to all of the social influences encompassing Factor 4 that affect individuals’ donation decisions. Specifically, i.e., the influence of others, donating to fulfill a religious obligation and effective promotion by the organization ranked highest among members of this group and with mean importance ratings that were nearly all significantly higher compared to the other two groups. Consistent with apparently being more subject to the social influence of an organization’s promotional efforts, Segment 3’s mean importance rating of the organization’s wide-spread reputation was significantly higher than the other two groups.

Finally, Segment 3 ranked the two economic considerations affecting the donation decision, i.e., obtaining a tax write off and one’s financial ability to donate higher than did the other two segments. Additionally, Segment 3’s mean importance rating of obtaining a tax write-off was significantly higher than that of Segments 1 and 2. Personal income and tax considerations taken together made up one of the four motivations (along with reciprocity, self-esteem enhancement, and career motives), categorized by Dawson (1988) to trigger donations to charitable organizations. All in all, because members of Segment 3 are highly susceptible to external influences affecting the donation decision, including marketing inducements offered by the charitable organization, this group will be hereafter referred to as the impressionable segment (or “impressionables”).

5.2.2 Demographics

Comparative demographic profiles of the three segments are presented in Table 5. No significant differences were found between members of the three segments on the basis of gender, age, and household income levels. Likewise, no intergroup differences were observed regarding their level of formal education, household size, ethnicity and marital status.

As noted earlier, past studies that have examined the impact of specific demographic factors on donation behavior have produced varied and sometimes conflicting results. Our research points to segments of donors that share similar socio-demographic characteristics, and this homogeneity suggests that significant differences along psychological and social influences as well as other factors can exist between similar demographic profiles of donors. This was shown by the distinct differences between the three segments regarding the importance of 27 motivators in the donation decision. It appears that it is these distinctions that should primarily inform differentiated marketing mix approaches on a segmented basis used by charities.

5.2.3 Information sources

Subjects were asked to identify their top three most effective choices among twenty sources for information for stimulating their interest in making charitable contributions (see Table 6). Social media and Word of mouth were the most preferred information outlets by each segment. Additionally, fund raising events and general community events ranked 3rd and 4th respectively for each segment. However, intergroup differences revealed by cross tabulation analysis appeared to correspond to the distinctive motivational aspects of each segment explained earlier.

The Intrinsic members made significantly more use than the other two groups of newsletters (at the 0.05 level) and personal contact (at the 0.10 level) with the charitable organization as sources of information. Since these individuals are particularly motivated by the intrinsic benefits of contributing such as having a personal connection with the charity or cause and helping one’s local community, it would follow that they would be more inclined to prefer personalized and in depth methods of communication from charitable organizations.

In comparison to the other two groups, the skeptics preferred the organization’s website significantly more as a means of stimulating their interest in a charity or cause related organization. This would be consistent with the more analytical nature of skeptic members and their consequent desire to find self-directed sources for uncovering substantial information about a charity or cause. Furthermore, in comparison to the other segments, it appears that television is regarded by skeptics as a significantly more useful means of dispensing in depth information about the organization and the cause it represents.

The impressionables deemed several traditional forms of advertising, namely, magazines billboards and direct mail to be significantly more effective in the donation decision than did the other two segments. This is consistent with the findings that this group is more prone to the influence of external stimuli provided by these types of promotional channels as means of stimulating their contribution behavior. These individuals rely significantly more on the social influences encompassing Factor 2 (extrinsic Inducements, as shown in Table 2). This is consistent with the additional finding that this segment is significantly more prone than the other two segments to the impact of testimony coming from others, particularly by way of schools as far as stimulating their donation behavior.

Respondents were also asked to rate how often they used various social media platforms (see Table 7). The most often utilized platforms by each of the three segments were YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. This is an expected finding, given that these avenues are the most widely utilized social media platforms in general (Robinson, 2021). The only significant intergroup distinction was the finding that the intrinsic segment used Facebook more than the skeptics group. Impressionables made more use of Snapchat than did the skeptics. Both of these differences were significant, but only at the 0.10 level. It therefore seems reasonable to conclude that social media in general is a key source of information referred to by all segments but, likely due to the similarity in demographic characteristics between the segments, there exists no appreciable difference between the groups as far as the type of social media platform used.

5.2.4 Types of charities/causes

Cross tabulation analyses was also used to compare the three segments in terms of the types of charities/causes they were most compelled to support (Table 8). All three segments most preferred to contribute to the causes of education and poverty Consistent with their comparatively greater other-oriented nature, the intrinsics were more drawn to the cause of poverty (albeit at only at a 0.10 level of significance) and significantly more inclined (at the 0.05 level) to support civil rights causes than the other two groups of donors. The only other area of differentiation between the three groups was that the impressionables rated military related causes to be significantly more compelling than did the other two groups. However, this particular cause ranked no higher than 10th out of the 13 options examined across all of the segments. It should also be noted that child wellbeing related causes ranked 4th among the 13 options for each of the three groups. Aside from these intergroup differences, the three segments were quite similar regarding the types of charities or causes they were most inclined to support.

6 Discussion/management implications

Durango-Cohen et al. (2013) suggests that donor segmentation research attempting to predict future donations should not be limited to past behavior, specifically recency, frequency and monetary value (RFM) statistics. More comprehensive predictors can be gleaned by focusing on the determinants of such behavior, and a useful starting point for doing so is to compare donor segments on the basis of socioeconomic variables. However, Royne Stafford and Tripp (2000) point out that while demographic characteristics are useful descriptors of segments, other factors must also be examined in order to develop fuller profiles of donor groups (Clopton et al., 2006; Colbert, 2014). A major contribution of this study is its focus on understanding the similarities and distinctions between donor groups that share similar contribution behaviors and demographic characteristics. What emerges are insights into more focused marketing measures based on motivational factors that can be taken to stimulate donations by such segments of contributors. We identify distinct intrinsic, skeptic and impressionable groups of contributors to whom tailored marketing approaches can be directed, particularly in the areas of promotion messaging as well as distribution channels for submitting donations.

6.1 Promotion messaging

In order to stimulate contributions and avoid wasted promotional efforts, the content of a charity’s message to potential donors should conform to the nature and desires of its target markets. Likewise the message should be encoded using language (verbal and nonverbal) that is preferred by the recipients. As noted by Mainwaring and Skinner (2009), such an approach is consistent with the communication principle of Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) which proposes that people respond more positively to communications presented to them using sensory representation systems (words, pictures, feelings) that are preferred by the recipient. However, similar to the study conducted by Sargeant and Ewing (2001), our focus is on the basic nature and content of the message rather than its sensory representation facets.

Regarding the content of the charity’s message, it is essential that the causal organization convey evidence of its trustworthy reputation to all groups of individual donors as this factor was a highly ranked motivator across all segments of intrinsics, skeptics and impressionables. This finding is consistent with the study of de Vries et al. (2015) who contend that trust and confidence in the organization is a key determinant of the donation decision across all donor groups. These researchers also note that trust is a complex concept in that it is brought about by a variety of causal factors. It would appear in this study that trust in a charity must be fostered by charitable organizations that clearly convey both its purpose and how it uses donor funds. Again, these factors of transparency were deemed highly important motivators in this study by all donor segments. This result is also consistent with the contention of de Vries et al. (2015) and Handy (2000) that potential donors are more likely to trust organizations and support them if their need for information is met about the how the charity is managed.

However distinctions in messaging to different segments are also suggested by this research. Again, Hou et al. (2014) suggest anticipation of the psychological and social benefits of contributing can serve as a strong motivator, and this appears to particularly be the case for the intrinsic group of donors. Therefore, the intrinsic benefits one derives by being altruistic should be communicated particularly in terms of explaining how donor funds help one’s local community and conveying the possibility of the donor’s personal connection with the charitable cause. The impact of one’s personal identification with the charity is also supported by the research of Hou et al. (2014) who found that donations are strongly related to the donor’s identification with the charitable organization. Furthermore, Sargeant and Ewing (2001) and Bennett (2006) found that the contributor’s personal experience with the problem addressed by the charity, e.g., being personally afflicted with a certain medical condition, or having a relative with the same medical condition stimulates one’s willingness to contribute.

Appeals to egoistic motivations should also be particularly directed to members of the intrinsic group. For example, the personal gratification one experiences by donating could be depicted through emotionally themed advertising, such as perhaps depicting an individual with a medical condition that has been alleviated by the generous contributions provided by donors.

Relative to the other two segments, building knowledge and awareness of the charitable organization, including the nature of its mission and its utilization of donor funds is especially important in targeting the skeptic members. While appealing to the philanthropic and egoistic desires held by this segment are important to them as well, members of this group are particularly concerned that their contributions will be effectively put to use in furthering the organization’s cause. It is therefore recommended that promotion outreach efforts in targeting this group provide specific evidence of how donors’ charitable contributions have helped the organization to realize its mission. As presented earlier, seeing tangible evidence of the charitable organization’s effectiveness was a significantly more important motivator to the skeptics than the other segments.

It has been shown that the donation behavior of the impressionables is particularly influenced by extrinsic inducements, including being presented with a compelling mission statement by the charitable organization, its widespread reputation, expressions of appreciation by the charitable organizations, and marketing measures aimed at attracting donor support such as gift incentives. Like the skeptics, this segment desires ample information and awareness about the nature, importance and effectiveness of the charitable organization as well as the criticality of its need for financial assistance. Effective means of meeting these expectations would be for the organization to present compelling stories (particularly in video form) and testimonial themed advertising as these types of inducements were shown in this study to be particularly important motivators for contributing by members of the skeptics group.

The significant impact of external stimuli upon the impressionables include group influence from family, friends as well as promotion measures directed at this segment by charitable organizations. Promotion that involve expressions of appreciation, including thanking donors, providing gift incentives, and offering gift matching programs should be particularly targeted at members of this group. The findings of Bennett (2006) provide evidence of the positive impact that expressions of appreciation have in establishing and maintaining relationships between charities and donors, and this can be administered in a wide variety of methods from a simple thank you to offering gift inducements.

Impressionables also stand out in terms of concerns about their personal economic circumstances related to contributing, specifically regarding their financial ability to do so and the possible tax benefits derived from donating. Therefore, in order to particularly appeal to this segment, marketing measures by charities should include offering financially manageable gift giving programs as this was motivator found to be significantly more important by impressionables. Furthermore, in order to appease their possible unease about their financial ability to donate, charitable organizations should impart the message that even a small donation can be important in helping the charity to realize its mission (Müller et al., 2014). Furthermore, arrangements in which donations (however small) are matched by the individual donor should also be implemented and clearly communicated to attract members of this group.

6.2 Distribution strategy/methods of making donations

In the case of the marketing efforts of charitable organizations to attract donor funding, distribution measures would involve methods made available by the entity for donors to submit donations. Similar to the distribution of goods and services, the marketer should attempt to make the means of making donations convenient and secure. Bennett (2006) suggests that offering a variety of channels for donors to submit contributions serves to enhance the length of the relationship between the charitable organization with the donor. Never the less, donation options should be prioritized to some degree in order to appeal to the particular desires of each segment of donors. To this end, survey respondents were asked to indicate their most preferred method to submit a donation to a nonprofit organization. Here, the rankings of each segment were tallied and cross tabulation analyses was used to compare intergroup responses (Table 9). It was found that the most favored means of donating across all segments were through the organization’s website, via mobile payment services (e.g., PayPal), in person donations and contributing at fund raising events. However, there were two areas of significant differences between the three segments. Intrinsics and skeptics preferred to donate through the organization’s website significantly more than was the case for impressionables. The difference here may be due to the instrinsics’ apparent tendency to readily act upon their desire to find altruistic and egoistic reasons for donating. When these reasons are found through the charity’s website content and the inclination for donating is triggered, the intrinsic member is therefore inclined to readily make a donation through this medium. Skeptics, in particular seek substantial information about a charitable organization before committing funds. They evidently tend to seek such information through the organization’s website and are therefore inclined to make the donation through this avenue when ample material about the charitable organization is provided.

Other areas of significant differences were that impressionable members preferred donating through their places of work and at fund raising events significantly more than did the other two segments. This intergroup difference can be attributed to the fact that these avenues of contributing involve the presence of at least some degree of group pressure on the individual and impressionables are generally more subject to such social influence in their donating behaviors.

7 Conclusion

Our research contributes to an apparent gap in the literature in that it takes a data driven, post hoc and holistic approach to segmentation in which numerous bases for grouping individual donors are examined. These include socio-economic, behavioral and motivational determinants of contribution behavior. Consequently, a key finding from our study is that markedly distinct groups of contributors can exist, even between segments that share similar demographic characteristics and donation behaviors. This suggests that the major criteria for segmentation is likely to be found in other areas, principally pertaining to the motivational bases for contributing. These include intrinsic and egoistic reasons for making donations as well as the characteristics and attributes of the charitable organizations itself. It is these factors that should be taken into account in developing differentiated marketing measures in such areas as promotion messaging and donation channels that can be applied according to the particular preferences of each segment of donors.

Some limitations are worth mentioning which limit the generalizability of our results and should be taken into account in future research. Our study explores subjects within only one major metropolitan locale, the San Francisco Bay Area. Also, our study is not longitudinal and therefore does not examine the development and determinants of donation behavior over a lengthy period of time.

References

Aggarwal, P. (2002). The effects of brand relationship norms on consumer attitudes and behavior [Doctoral dissertation, University of Chicago] (Order No. 3048359). Available from ABI/INFORM Collection. (305517585). https://stmarys-ca.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.stmarys-ca.idm.oclc.org/dissertations-theses/effects-brand-relationship-norms-on-consumer/docview/305517585/se-2?accountid=25334

Andreoni, J. (1990). Impure altruism and donations to public goods: A theory of warm—Glow giving. Economic Journal, 100(401), 464–477. https://doi.org/10.2307/2234133

Andreoni, J., & Petrie, R. (2004). Public goods experiments without confidentiality: A glimpse into fund-raising. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1605–1623. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(03)00040-9

Bachke, M., Alfnes, F., & Wik, M. (2014). Eliciting donor preferences. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary & Nonprofit Organizations, 25(2), 465–486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-012-9347-0

Bennett, R. (2006). Predicting the lifetime durations of donors to charities. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 15(1/2), 45–67. https://doi.org/10.1300/J054v15n01_03

Besana, A., & Esposito, A. (2019). Fundraising, social media and tourism in American symphony orchestras and opera houses. Business Economics, 54(2), 137–144.

Boenigk, S., & Scherhag, C. (2014). Effects of donor priority strategy on relationship fundraising outcomes. Non Profit Management and Leadership, 24, 307–336. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21092

Clary, E. G., Ridge, R. D., Stukas, A. A., Snyder, M., Copeland, J., Haugen, J., & Miene, P. (1998). Understanding and assessing the motivations of volunteers: A functional approach. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 74(6), 1516–1530. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1516

Clopton, S. W., Stoddard, J. E., & Dave, D. (2006). Event preferences among arts patrons: Implications for market segmentation and arts management. International Journal of Arts Management, 9(1), 48–59.

Colbert, F. (2014). The arts sector: A marketing definition. Psychology & Marketing, 31(8), 563–565. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20717

Dawson, S. (1988). Four motivations for charitable giving: Implications for marketing strategy to attract monetary donations for medical research. Journal of Health Care Marketing, 8, 31–37.

de Vries, N. J., Reis, R., & Moscato, P. (2015). Clustering consumers based on trust, confidence and giving behavior: Data-driven model building for charitable Involvement in the Australian not-for-profit sector. PLoS ONE, 10(4), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122133

Demir, F. O., Kireçci, A. N., & Yavuz Görkem, Ş. (2020). Deepening knowledge on volunteers using a marketing perspective: Segmenting Turkish volunteers according to their motivations. Nonprofit & Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 49(4), 707–733. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764019892623

Dolnicar, S., & Randle, M. (2007). What motivates which volunteers? Psychographic heterogeneity among volunteers in Australia. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary & Nonprofit Organizations, 18(2), 135–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-007-9037-5

Durango-Cohen, E., & Balasubramanian, S. (2015). Effective segmentation of university alumni: Mining contribution data with finite-mixture models. Research in Higher Education, 56(1), 78–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-014-9339-6

Durango-Cohen, E., Torres, R. L., & Durango-Cohen, P. (2013). Donor segmentation: When summary statistics don’t tell the whole story. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 27(3), 172–184.

Garber, L. L., Jr., & Muscarella, J. G. (2000). Consumer based strategic planning in the nonprofit sector: The empirical assessment of a symphony audience. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 8(1), 55–86. https://doi.org/10.1300/J054v08n01_06

Gneezy, U., Keenan, E. A., & Gneezy, A. (2014). Avoiding overhead aversion in charity. Science, 346(6209), 632–635. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1253932

Handy, F. (2000). How we beg: The analysis of direct mail appeals. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 29(3), 439–454.

Heiser, R. S. (2006). Normative influences in donation decisions. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 15(1), 127–149.

Hou, J., Eason, C. C., & Zhang, C. (2014). The mediating role of identification with a nonprofit organization in the relationship between competition and charitable behaviors. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 42(6), 1015–1028. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2014.42.6.1015

Hoye, S. (2007). Marketing techniques alone won’t advance a charity's cause, experts say. The Chronicle of Philanthropy 19(19). Gale Academic OneFile. Retrieved 30 March, 2021, from https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A166755183/AONE?u=mora54187&sid=AONE&xid=6445f3e9

Johnson, J. W., & Grimm, P. E. (2010). Communal and exchange relationship perceptions as separate constructs and their role in motivations to donate. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 20(3), 282–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2010.06.018

Johnson, J. W., Peck, J., & Schweidel, D. A. (2014). Can purchase behavior predict relationship perceptions and willingness to donate? Psychology & Marketing, 31(8), 647–659. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20725

Kemp, E., Kennett-Hensel, P., & Kees, J. (2013). Pulling on the heartstrings: Examining the effects of emotions and gender in persuasive appeals. Journal of Advertising, 42(1), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2012.749084

Kohlberg, L. (1975). The cognitive-developmental approach to moral education. The Phi Delta Kappan, 56(10), 670–677.

Lee, B., Fraser, I., & Fillis, I. (2017). Nudging art lovers to donate. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 46(4), 837–858. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764017703708

Mainwaring, S., & Skinner, H. (2009). Reaching donors: Neuro-linguistic programming implications for effective charity marketing communications. Marketing Review, 9(3), 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1362/146934709X467785

Müller, S. S., Fries, A. J., & Gedenk, K. (2014). How much to give? The effect of donation size on tactical and strategic success in cause-related marketing. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 31(2), 178–191.

Omoto, A. M., & Snyder, M. (1995). Sustained helping without obligation: Motivation, longevity of service, and perceived attitude change among AIDS volunteers. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 68(4), 671–686. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.4.671

Randle, M., & Dolnicar, S. (2009). Not just any volunteers: Segmenting the market to attract the high contributors. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 21(3), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495140802644513

Robinson, R. (2021). 7 Top Social Media Sites in 2020. Retrieved 26 March, 2021, from https://spark.adobe.com/make/learn/top-social-media-sites/

Royne Stafford, M., & Tripp, C. (2000). Age, income, and gender: Demographic determinants of community theater patronage. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 8(2), 29–43.

Saito, K. (2015). Impure altruism and impure selfishness. Journal of Economic Theory, 158, 336–370.

Sargeant, A., & Ewing, M. (2001). Fundraising direct: A communications planning guide for charity marketing. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 9(1), 185–204.

Sargeant, A., Foreman, S., & Liao, M.-N. (2002). Operationalizing the marketing concept in the nonprofit sector. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 10(2), 41–65.

Shemyatikhina, L., Shipitsyna, K., & Usheva, M. (2020). Marketing management of a nonprofit organization. Economic and Managerial Spectrum, 14(1), 19–29.

Shields, P. O. (2009). Young adult volunteers: Recruitment appeals and other marketing considerations. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 21(2), 139–159.

Smith, J. N. (2018). The social network? Nonprofit constituent engagement through social media. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 30(3), 294–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2018.1452821

Smith, K. D., Keating, J. P., & Stotland, E. (1989). Altruism reconsidered: The effect of denying feedback on a victim’s status to empathic witnesses. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(4), 641–650. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.4.641

Sujo, T., Kureshi, S., & Vatavwala, S. (2020). Cause-related marketing research (1988–2016): An academic review and classification. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 32(5), 488–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2019.1606757

Supphellen, M., & Nelson, M. R. (2001). Developing, exploring, and validating a typology of private philanthropic decision making. Journal of Economic Psychology, 22(5), 573–603.

Taylor, J. A., & Miller-Stevens, K. (2019). Relational exchange in nonprofits: The role of identity saliency and relationship satisfaction. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.1618

Terech, A. (2018). An introduction to marketing and branding. Generations, 42(1), 45–49.

Yoo, S.-C., & Drumwright, M. (2018). Nonprofit fundraising with virtual reality. Nonprofit Management Then Leadership, 29(1), 11–27.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kolhede, E., Gomez-Arias, J.T. Segmentation of individual donors to charitable organizations. Int Rev Public Nonprofit Mark 19, 333–365 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-021-00306-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-021-00306-2