Abstract

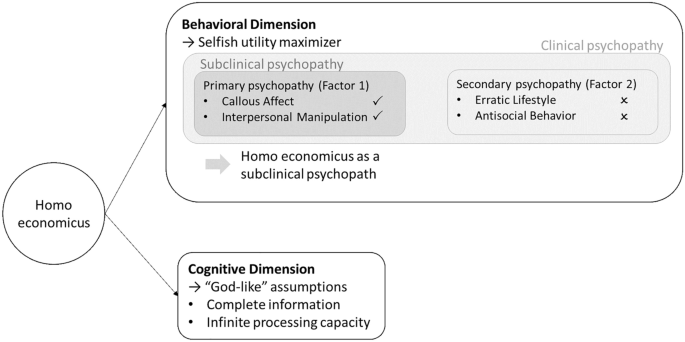

Since the beginning of business research and teaching, the basic assumptions of the discipline have been intensely debated. One of these basic assumptions concerns the behavioral aspects of human beings, which are traditionally represented in the construct of homo economicus. These assumptions have been increasingly challenged in light of findings from social, ethnological, psychological, and ethical research. Some publications from an integrative perspective have suggested that homo economicus embodies to a high degree dark character traits, particularly related to the construct of psychopathy, representing individuals who are extremely self-centered and ruthless, without feelings of remorse or compassion. While a growing body of research notes such a similarity on a more or less anecdotal basis, this article aims to explore this connection from a more rigorous perspective, bridging insights from psychological, economic, and business research to better understand the potentially dark traits of homo economicus. The analysis shows that homo economicus is not simply some kind of psychopath, but specifically a so-called subclinical or Factor 1 psychopath, who is also referred to as a “corporate psychopath” in business research. With such an analysis, the paper adds an additional perspective and a deeper psychological level of understanding as to why homo economicus is often controversially debated. Based on these insights, several implications for academic research and teaching are discussed and reflected upon in light of an ethics of virtue and care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

From the perspective of the philosophy of science, each scientific discipline is characterized by some basic assumptions. In disciplines such as philosophy, anthropology, sociology, but also in business research and economics, the assumed concept of a human being (“Menschenbild,” see, e.g., Zichy, 2020) is one of these fundamental assumptions. While in philosophy since the Enlightenment a human being is conceived of as a rational actor in a very broad sense, also from a moral capabilities perspective (e.g., in Kant’s moral philosophy), in traditional theoretical models of economics and business this rationality has been strongly narrowed to a ruthless, selfish pursuit of material benefits. This sole, opportunistic pursuit of material advancement is well reflected in the concept of homo economicus, the standard concept of an actor in neoclassical economics.

Interestingly, the core dispositions and motivations of homo economicus have been debated since the creation of the concept in the nineteenth century. In particular, it often has been noted that the homo economicus’ motivational dispositions, which have been made the foundation of orthodox economics, i.e., ruthless selfishness and greed, would be theologically considered as cardinal or mortal sins (Martinás, 2010; Verburg, 2018; Zamagni, 2011). Beyond such a moral analysis, in the last decade, some publications have stated that homo economicus seems to incorporate dark character traits, and especially signs of psychopathy (e.g., Bailey, 2017; Davies, 2016; Hoffman, 2011; Stout, 2014). Yet, there has been very little systematic and deeper psychological investigation into the core traits of homo economicus. Such an analysis appears to be relevant for a number of reasons. First of all, the concept of homo economicus is still critically discussed in contemporary business ethics research as a questionable model for human behavior (e.g., Friedland & Cole, 2019; Haarjärvi & Laari-Salmela, 2022; Racko, 2019). A psychological analysis could provide an additional, highly interesting perspective to this ongoing discussion. Furthermore, homo economicus, even if not always made explicit, is still prevalent in fundamental economic, managerial, and organizational theories (Melé & Cantón, 2014). Although business research applies a variety of methods and theoretical backgrounds, the homo economicus concept is, for instance, the basis of microeconomic firm profit or individual utility maximization (e.g., Parkin, 2014; Pindyck & Rubinfeld, 2018). Likewise, key behavioral dispositions of homo economicus are reflected in principal-agent theory (Gintis & Khurana, 2016). With regard to capital markets, traditional instruments like the Capital Asset Pricing Model are built on assumptions of economic rationality (Baker & Ricciardi, 2014). Moreover, the concept is generally the basis for rational choice theory (e.g., Gilboa, 2012) and therefore part of all approaches based on this concept, which especially holds for a great number of analytical research that relies on formal modeling. Finally, besides economics and business, the concept has also been adopted in other disciplines like sociology, politics, or law (e.g., Guzman, 2008; Hechter & Kanazawa, 1997; Parsons, 2005; Zafirovski, 2014).

As this paper argues, the fundamental selection of models is not just a theoretical issue, these choices also matter in practice. Specifically, the arguments that homo economicus “is just a model” or “it’s simply an ‘as if’ assumption” with some predictive value (e.g., Friedman, 1976), fall short for several reasons (also see Dosi et al., 2021). Besides the counterargument that such an “as if” approach would not do sufficient justice to supporting the study of a real decision-maker, there is an even potentially stronger argument with regard to the real-world implications of model choices on business and policy-making processes, on which this paper will elaborate. In such vein, the paper is not only solely theoretically insightful but also creates several links to practice. Although homo economicus is evidently not a real person, it is not solely an abstract, imaginative concept detached from any impact on reality. Rather, it represents a distinct artifact of thinking about basic rules in business and human interaction in general, which also reflects back on and influences the reasoning and acting in these contexts (Linstead & Grafton-Small, 1990). This has several implications. First of all, as will be discussed, homo economicus still reverberates in corporate practice, for instance in competitive, individualistic environments and monetary incentive schemes. Equally, when academic theory is applied in practice, like in cases of economic deregulation, the implied concept of a human being matters (e.g., Fridman, 2010). In addition, the findings of this paper are also insightful with regard to academic teaching. As several studies have shown, teaching conveys certain basic values—at least implicitly, simply by the fact of model choice and the implied concept of humanity that was chosen (e.g., Frank et al., 1993; Ifcher & Zarghamee, 2018; Kowaleski et al., 2020; Racko, 2019). In such vein, for instance, the last financial crisis has been linked to at least implicitly taught values associated with homo economicus (Giacalone & Wargo, 2009; Melé, 2009; Melé et al., 2011). Also from a wider perspective, several corporate scandals with far-reaching organizational and societal consequences are discussed as being, at least partly, caused by internalizing economic rationality, and homo economicus as a representation of such rationality (Ong et al., 2022). Based on these considerations, several authors have called for a critical examination of the academic curricula for teaching business (Dierksmeier, 2011; Fougère & Solitander, 2023; Giacalone & Wargo, 2009; Gintis & Khurana, 2016; Waddock, 2020). Given the continuing criticism of homo economicus and the lack of systematic deeper analyses with regard to the potentially dark traits of this model, this paper conducts an analysis from a more rigorous psychological perspective.

As such, the paper is structured as follows. In the beginning, the paper will conduct a short review of the two major notions, i.e., first, the concept of homo economicus and second that of psychopathy is discussed. After presenting the two major concepts, both lines of thought are combined and homo economicus is systematically analyzed through a psychological lens. As a major finding, this paper shows that the core traits of homo economicus as an emotionally shallow, selfish, opportunistic, and manipulative agent can be psychologically described as psychopathic. Specifically, homo economicus shows strong traits of so-called subclinical psychopathy, which relates to the notion of corporate psychopathy widely applied in business research. After discussing this finding, several implications for business research and teaching are reflected upon through the lens of an ethics of virtue and care.

The Concept of Homo Economicus

Although an early discussion of traits resembling the concept later coined “homo economicus” can be traced back to the antiquities (Dixon & Wilson, 2012), the notion is particularly linked to the advent of the classic economic theory in the eighteenth and nineteenth century. According to the seminal review by Persky (1995), it was shaped by John Stuart Mill, postulating that economic analysis should restrict itself to the concept of an agent primarily motivated by “the desire of wealth, [.] aversion to labour, and desire of the present enjoyment […]” (Mill, 1844, p. 138). Yet, the exact terminology was only later introduced by authors like John Kells Ingram and John Neville Keynes in their critical discussion of Mill’s economic groundwork. Subsequently, it has been frequently assumed that the concept was strongly influenced by the work of Adam Smith given that in his Wealth of the Nations (Smith, 1804), he argues that economic exchange shall be seen primarily in light of mutual self-interest instead of social motives such as altruism. This view is, however, for its simplicity challenged by the newer Adam Smith research (e.g., Hühn & Dierksmeier, 2016), particularly with regard to his second groundbreaking and potentially complementary work on The Theory of Moral Sentiments (Smith, 1761). A great leap in the development of the modern understanding of homo economicus is provided by the development of neoclassical economics with a stronger emphasis on mathematical formalization, which in turn was heavily influenced by physics, and in specific, deterministic mechanics and thermodynamic equilibrium theory (Smith & Foley, 2008). With regard to the “forces” leading to economic equilibria, self-interest coupled with a possession of complete information became the standard doctrine of economic models in neoclassical approaches. These assumptions are embedded in the concept of homo economicus as an agent solely concerned with maximizing utility while possessing a temporally stable preference structure. This structure is independent of others—or to say more precisely: covers the needs of others only to such an extent as these others are deemed beneficial to the homo economicus’ own ends (Kirchgässner, 2008). The rationality of homo economicus is therefore strictly based on the own benefit and represents a thinking in purpose-means relationships (Anderson, 2000; Elster, 1989). Although it is sometimes argued that the model of homo economicus could be conceived of as being concerned with the satisfaction of arbitrary, e.g., also altruistic, needs (England, 2003), like in the works of Becker (1981, 1993), such an extension to the satisfaction of all conceivable preferences falls short in at least two respects. First, defining all actions as utility maximizing makes the model a tautology where every conduct is ex-post explained by utility, thus lacking any analytical sharpness, being factually non-testable and logically circular (Ostapiuk, 2021; Stout, 2014). Second, from a conceptual point of view, the homo economicus model is de facto often understood as narrowed to the traditional, already elaborated motives (England, 2003): a maximization of material benefits, as for instance measured in discounted cash flows or net present value as a traditional measure of rational decision-making (Magni, 2009). As such, homo economicus is a “single-minded income-maximizing economic actor” (Pearlstein, 2016) or as Fleming (2017, p. 98) puts it, a “dollar-hunting animal” represented in “the monetised principle of pure utility.”

Moreover, the academic examination is frequently limited insofar as the controversies often mix two distinct features of homo economicus, which, if not clearly disentangled, blurs the debate on the concept and which this paper therefore shall delineate more precisely: namely a cognitive and a behavioral assumption of the model. In the cognitive dimension, the information status and computational capabilities of the actor are covered. In such vein, it is assumed that homo economicus possesses complete information, has no restrictions in computation, and can adapt at infinite speed to a change in information. Unsurprisingly, these evidently stark assumptions have been heavily criticized, particularly in the domain of bounded rationality research initiated by Herbert Simon, who harshly criticized the God-like, “Olympian model” (Simon, 1983, p. 34) of homo economicus, which he assigned to “Plato’s heaven of ideas” (p. 13). In contrast, Simon’s groundbreaking work emphasizes that human individuals are not fully knowledgeable and deviate from the standard economic maximization paradigm by “satisficing” (i.e., being satisfied with an achievement of a previously defined “good” result level) instead of “optimizing,” which has in consequence inspired several streams of research until present day (also see Simon, 1983). These are, for instance, the “biases and illusions” research by Kahneman and Tversky, which investigates the deviation from standard economic rationality as cognitive biases, mostly in experimental contexts (e.g., Kahneman, 2012; Kahneman & Tversky, 1979; Tversky & Kahneman, 1974), and the field of “ecological rationality” in the tradition of Gigerenzer, emphasizing in opposition to the “biases and illusions” research that heuristic approaches often deliver good solutions in real problem solving situations, i.e., under consideration of the real problem environment (e.g., Gigerenzer, 2004; Gigerenzer & Brighton, 2009; Gigerenzer & Gaissmaier, 2011; Gigerenzer & Goldstein, 2016).

Besides these cognitive assumptions, even more interesting for the present paper are the behavioral assumptions of the homo economicus model. From this view, homo economicus can be linked back to the original considerations debated in the context of Mill’s economic theory, i.e., an individual’s conduct that is structured by a strict pursuit of self-interest, as said, mostly reduced to material benefits to avoid a motivationally arbitrary and tautological model. Given the total absence of any genuine social concerns, the model is based on an opportunistic exploitation of any options available to increase personal wealth. The individual advantage is therefore pursued without empathy, feelings of remorse or guilt, any feelings for others at all, and only based on the prospect of a possible enrichment. These characteristics are widely reflected in information economics (e.g., Birchler & Bütler, 2007; Macho-Stadler & Pérez-Castrillo, 2001), for instance in the context of adverse selection or hidden action, and considerations on the importance of designing incentive and control systems (see e.g., Merchant & Van der Stede, 2017) to limit discretionary behavior (Picot et al., 2008). These assumptions also have been strongly contested from an empirical perspective. In particular, behavioral research has emphasized the importance of not neglecting stable social traits such as altruism, fairness, or reciprocity (Bolton & Ockenfels, 2000; Bolton et al., 2005; Fehr & Fischbacher, 2002; Fehr & Schmidt, 2006; Fischbacher et al., 2001; Gächter & Falk, 2002). The restriction to a ruthless, selfish, and opportunistic conduct, seeing others merely as a means to maximize the own advantage, has led to a widespread criticism of orthodox economics as a “dismal science” (Aldred, 2009; Brue & Grant, 2013; Levy, 2002; Marglin, 2008). However, still, a more systematic analysis of these assumptions from the perspective of dark character traits, and psychopathy in particular, needs to be conducted.

The Concept of Psychopathy

As a first general definition, the notion of psychopathy refers to a “distinct psychiatric illness marked by serious behavioral deviancy in the context of intact rational function” (Patrick, 2018, p. 4). According to Hare (1999, p. 34) psychopathy must be considered a syndrome, i.e., “a cluster of related symptoms,” as shown in a morally deviant, ruthless, and selfish conduct. It is important to note that in comparison to insanity or madness, psychopaths commit their moral transgressions and crimes in full clarity of conduct—they simply do not care for others and the harm inflicted on them (Glenn et al., 2009). Interestingly, from the first concepts specifying psychopathy in the nineteenth century and until recent times, a wide range of psychological research has focused on the so-called clinical psychopath, an individual who not only lacks any affection and empathy for others but likewise shows a serious lack of long-term-oriented conduct and behavioral control, leading to an unsteady life and frequent unrestrained outbursts of physical violence. As a result, these individuals tend to come into conflict with the law at an early age and often face imprisonment (Hare & Neuman, 2008). However, not all psychopaths are impaired in this way. Rather, there are individuals who possess some of the core traits of clinical psychopathy and yet are able to lead seemingly normal lives, be at first glance likable and charming, and even succeed in their individual careers. These individuals are referred to as subclinical psychopaths. This fact is summarized in the famous quote by Hare stating: “Not all psychopaths are in prison. Some are in the Boardroom” (as cited in Babiak et al., 2010, p. 174).

From a research perspective, the existence of such subclinical psychopaths has stirred increasing academic interest in recent decades, particularly in light of some spectacular collapses of once prestigious companies due to massive levels of executive misconduct and fraud (Lingnau et al., 2017). Interestingly, the prevalence of subclinical psychopaths has also been suggested as a reason for the last financial crisis (Boddy, 2011; Gregory, 2014; Marshall et al., 2013). To better understand the underlying phenomenon, it is helpful to deeper investigate the characteristics of psychopathy as a construct of two major, overarching factors (Babiak, 2016). Such a differentiation began with the seminal work by Cleckley (1941), who not only developed the modern concept of psychopathy by elaborating several core aspects of the syndrome but already noted that there are some individuals with psychopathic traits that could be highly successful in their careers. This research inspired Hare (1980) to develop the Psychopathy Checklist (PCL), which extended Cleckley’s notion with some additional, especially antisocial, tendencies often found in institutionalized psychopaths (Hare & Neumann, 2005, 2008). This scale was later revised to the PCL-R (Hare, 2003). In addition to its widespread use in the detection of psychopathy (e.g., Acheson, 2005; Falkenbach, 2007; Fritzon et al., 2020; Lynam, 2011), the PCL-R is also noteworthy because its empirical application has helped to shape a deeper conceptual understanding of the construct of psychopathy itself. Specifically, the empirical application revealed that the construct is composed of several subfactors that are insightful for classification, as the following discussion will show. As such, the PCL-R shows two major dimensions, or overarching factors of psychopathy, which can be further differentiated into two subfactors (Hare & Neumann, 2005, 2008) (see Table 1 and Fig. 1).

The first major factor of psychopathy refers to an interpersonal and affective dimension. In the affective dimension (callous affect) these individuals are extremely ruthless and coldhearted, showing a deficiency in emotional responses, particularly when others are harmed. They are further lacking any conscience, feelings of guilt or remorse, and do not take responsibility for their actions. The second subfactor of the first dimension is interpersonal manipulation. I.e., such individuals do not refrain from using and misusing others to reach their goals, which also includes deceitful behavior like cheating and lying on a habitual basis. This is especially easy for psychopaths because they feel less cognitive dissonance in doing so (Murray et al., 2012). Although individuals with such trait may appear likable and charming at first glance, they are entirely self-focused and do not care about others, merely using them for personal advantage. Therefore and in summary, individuals with an elevated Factor 1 are characterized by superficial charm, an extreme lack of empathy or compassion, leading to a ruthless, manipulative conduct without feelings of shame, remorse, or guilt (Hare & Neumann, 2005, 2008). Besides Factor 1 as a core element of the notion of psychopathy (Harpur et al., 1989; Herpertz & Sass, 2000), Factor 2 characterizes issues with an individual’s long-term planning and behavioral control, leading to an unsteady lifestyle, impulsive thoughtlessness, generally openly displayed irresponsible and antisocial conduct, and therefore most often early delinquency. This second factor can be differentiated in an erratic lifestyle, particularly focusing on a lack of long-term-oriented conduct and an unsteady life, and antisocial behavior, as for instance represented in violent outbursts and law-breaking, leading to early criminal behavior (Hare & Neumann, 2005, 2008).

It is worth noting that there has been some discussion on the latter subfactor. As such, Cooke and Michie (2001) have argued for a three-factor model that drops the subfactor of antisocial behavior because this factor includes blue-collar crime tendencies, which they argue to be consequences of traits and not the traits themselves. However, as Hare and Neumann (2005, 2008) argue in return, dropping out antisocial behavior would also exclude relevant aspects such as poor behavioral control typical of clinical psychopaths. In this paper, we cannot attempt to remedy such internal psychological discussion. However, as we shall discuss, there are some good reasons to apply the 2 by 2 model in the following analysis. First, it may be highly interesting to evaluate homo economicus also in terms of the behavioral control aspect, which would be excluded if the antisocial behavior subfactor were not examined. Such an aspect seems worth discussing with homo economicus and provides a deeper analysis. Moreover, this model is useful for distinguishing between clinical and subclinical psychopathy (Babiak, 2016), which, as the following analysis shows, is very insightful. With regard to such model, the traditional concept of psychopathy, i.e., clinical psychopathy, refers to individuals with a substantially elevated Factor 1 and Factor 2. Consequently, these are ruthless and coldhearted individuals with considerable behavioral problems and an unsteady lifestyle. In contrast, subclinical psychopaths, who are particularly interesting from a business research perspective, show an equally profoundly elevated Factor 1 but, at most, only a mildly elevated Factor 2 (Babiak, 2016). These individuals are therefore extremely coldhearted, opportunistic, and without remorse or guilt. Yet, they can plan very strategically and possess a relatively normal behavioral control, enabling them to appear even as charming and likable at first glance as they are masters of concealing their dark traits. As a result, such individuals are frequently able to climb the corporate ladder, which is especially propelled in Western cultures (Boddy et al., 2010a; Stout, 2005). This is facilitated by an increasing expectation of frequent job changes in leadership positions (Boddy et al., 2021) and internally as well as externally often turbulent, competitive business environments. The ascent of such individuals is also confirmed in several empirical investigations. For example, Babiak et al. (2010) found that up to 6% of top managers showed psychopathic traits while Fritzon et al. (2017) found even 21% of managers to display substantially elevated psychopathic traits in the supply chain context. In comparison, the prevalence in the general population is merely about 1%. These subclinical psychopaths are referred to by a variety of terms. Besides the simple term as a “Factor 1 psychopath,” they are also referred to as “organizational psychopath” (e.g., Boddy, 2006), “executive psychopath” (e.g., Morse, 2004), “corporate psychopath” (Babiak & Hare, 2019; Boddy, 2005; Brooks et al., 2020; Lingnau et al., 2017), or “successful psychopath” (e.g., Benning et al., 2018; Board & Fritzon, 2005; Hare & Neumann, 2008; Hervé, 2007; Weber et al., 2008). In the following, we will refer to these individuals primarily as “corporate psychopaths.”

Analysis of Homo Economicus on Psychopathy

In order to systematically analyze the concept of homo economicus with regard to psychopathic traits, the PCL-R will be applied. As such, in the dimension of primary psychopathy, the first subfactor to be analyzed is callous affect, which refers to a deficiency in emotional responses, i.e., showing a shallow affect, no empathy with others, a lack of remorse or guilt, and not taking responsibility. Looking at the discussion of homo economicus in the literature, already Boulding (1969, p. 10) identified the concept of homo economicus as someone who “counted every cost and asked for every reward, was never afflicted with mad generosity or uncalculating love, and who never acted out of a sense of inner identity and indeed had no inner identity even if he was occasionally affected by carefully calculated considerations of benevolence or malevolence.” Similarly, also Homans (1961, p. 79) concluded that the homo economicus essentially was “antisocial and materialistic, interested only in money and material goods and ready to sacrifice even his old mother to get them.” Finally, Sen (1977, p. 336) famously labeled the homo economicus a “rational fool” and a “social moron.” Also in newer publications, the callousness of homo economicus has been noted by emphasizing an extreme level of selfishness, i.e., homo economicus cares only about the personal utility and is therefore indifferent toward the needs of others, as long as these others are not necessary to advance the own benefits (Boddy, 2023; Kirchgässner, 2008). In such a reckless pursuit of self-interest, there is also no place for conscience, guilt, feelings of duty, and remorse, which represents a high degree of emotional detachment from others (Baron, 2014; Lingnau et al., 2017; Ogaki & Tanaka, 2019; Stout, 2012). As a result, “homo economicus is a clinical calculator of his own advantage, a ruthless pursuer of his own interest […]” (Mell & Walker, 2014, p. 17). Homo economicus “has no moral compunction, does not engage in actions just because some abstract social norms require doing so” and has no “feelings of guilt” (Ben-Ner & Putterman, 1998, p. 18). Lastly, concerning the aspect of taking responsibility, it is clear that homo economicus is ruthless and has “no responsibility for anyone” (Nelson, 1993, p. 292), except for potentially optimizing the own benefit. Thus, there is no genuine “responsibility for other people and future generations” (Siebenhüner, 2000, p. 18). Summarizing these statements, one can subsume that homo economicus shows a high degree of callous affect.

The second subfactor to be discussed is interpersonal manipulation, which comprises aspects of glib, superficial charm, a sense of grandiosity, pathological lying, and the tendency to manipulate others in order to achieve personal goals. Looking at the literature, homo economicus does not maintain genuine and deep personal relationships. As Davies (2016, p. 61) subsumes: “Homo economicus doesn’t have friends.” Rather, the instrumental rationality of homo economicus leads to a superficial interaction with others, which Dobuzinskis (2019, p. 105) describes as “all too glib.” The core traits of manipulative and untrustworthy conduct of this subfactor are well reflected in principal-agent theory stating that a principal has to assume untruthful reports and a general lack of commitment by an agent (Picot et al., 2008). In such vein, it can be stated with Williamson (1985, p. 51) that homo economicus will regularly apply “the full set of ex ante and ex post efforts to lie, cheat, steal, mislead, disguise, obfuscate, feign, distort, and confuse,” as long as such promises the realization of personal gain. Similarly, Hunt and Vitell (2015, p. 34) pointedly state that “homo economicus not only maximizes self-interest but does so with opportunistic ‘guile’.” Thus, homo economicus is “designed to cheat, lie, and exploit” (Dash, 2019, p. 26). Lastly, although homo economicus is evidently not designed as a Narcissist with a need for social affirmation (e.g., Miller et al., 2021), some sense of grandiosity implied in the model could be seen in the quote by Sen (1977, p. 336) stating that homo economicus is not only a “rational fool” but also “decked in the glory of his one all-purpose preference ordering.” In summary, the second subfactor is also well represented within the homo economicus model. It can be subsumed that homo economicus is extremely selfish, and merely considers others as a means to personal enrichment, also habitually applying methods of lying and cheating, using and misusing others to achieve personal benefit. Thus, in conclusion, both subfactors, i.e., callous affect and interpersonal manipulation are well echoed in the concept of homo economicus. Consequently, homo economicus represents to a large degree traits of the Factor 1 of psychopathy.

With respect to the Factor 2 of psychopathy, the first subfactor is erratic lifestyle comprising stimulation seeking, impulsive, short-term-oriented behavior, careless, irresponsible conduct, a lack of realistic goals, and a tendency toward a parasitic lifestyle. As a first aspect, stimulation seeking refers to the propensity to be easily bored and thus to seek out tense situations, such as regular participation in risky activities like skydiving. Generally, stimulation seeking is not implied in the concept of homo economicus as a cool-minded calculator (Mell & Walker, 2014). With regard to implied risk taking, an interesting aspect can be discussed. First of all, homo economicus is generally not inclined to make personally overly and unnecessarily risky decisions. However, homo economicus could very well accept substantial risks if they are ultimately borne by others, as was evident in the example of the massive risk taking that led to the financial crisis (Boddy, 2011). Such risk taking is however more rooted in the callous affect of Factor 1, i.e., based on a lack of emotions and not accepting responsibility if others are harmed. Concerning the items that refer to a lack of realistic long-term planning, i.e., living into the day and letting oneself carelessly and in a potentially self-harming, irresponsible way drift from one impulse to another, is clearly not embodied in the homo economicus model. Rather, as discussed, homo economicus is characterized by a mentally cool, emotionally detached, reflective, and goal-oriented conduct. However, a parasitic lifestyle could resonate with homo economicus to some degree insofar as the model very well implies a potentially opportunistic exploitation of others’ value creation. Yet, besides such minor indications, homo economicus does evidently not qualify for truly attesting an erratic lifestyle.

Lastly the subfactor of antisocial behavior shall be discussed, which comprises a substantial impairment in behavioral control (e.g., frequent violent outbursts), often already at an early age, juvenile delinquency, revocation of conditional releases, and criminal versatility. With regard to homo economicus, the concept reflects a ruthless, emotionally detached conduct, which, however, is combined with a very controlled, clear-minded, target-oriented decision-making and execution of plans and no tendency toward uncontrolled violence or physical misconduct. Consequently, homo economicus does not represent problems with behavioral control as for instance struggling with outbursts of violence and openly breaking the law. Yet, homo economicus could of course engage in a variety of criminal activities if such would appear to be personally profitable, however, in a reflective and controlled manner (e.g., Becker, 1968). Summarizing the discussion on the latter two subfactors, it became clear that no substantially elevated Factor 2 can be attributed to homo economicus. In comparison, as the previous discussion shows, homo economicus strongly represents psychopathic traits of Factor 1 of psychopathy. Thus, as a final result, the psychological analysis reveals that homo economicus is evidently a subclinical, i.e., corporate psychopath (see Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Discussion

The finding that homo economicus is a corporate psychopath is of particular interest for business ethics research as it provides a link to the increasing amount of publications indicating the extremely destructive potential of such subclinical psychopaths in business, as also several publications in this journal show (e.g., Boddy, 2011, 2017; Boddy et al., 2010b). Corporate psychopaths are generally associated with an organizational decline with regard to long-term revenue, employee commitment, and innovativeness (Boddy, 2017). They are responsible for a deteriorating work climate by bullying and demoralizing colleagues (Boddy & Taplin, 2016; Mathieu & Babiak, 2016; Sheehy et al., 2021; Valentine et al., 2018) and creating an atmosphere of fear (Boulter & Boddy, 2021). This, in turn, often leads to increasing sickness rates and sometimes even long-lasting and severe traumatization (Boddy & Taplin, 2016). Although corporate psychopaths present themselves in an eloquent manner, behind their shiny façade they are often less qualified than they appear, which they compensate by their eloquent communicative skills and self-confident demeanor (Babiak et al., 2010; Perri, 2013). There are also several incidents known of forgery of false diplomas and other credentials (Boddy & Taplin, 2016). Corporate psychopaths are also known to exert a negative impact on corporate sustainability decisions (Boddy et al., 2010b; Myung, et al., 2017). In addition, such individuals are generally considered unethical decision-makers (Stevens et al., 2012; Van Scotter & De Déa Roglio, 2020) and are prone to accept even crimes to achieve their goals (Lingnau et al., 2017; Ray & Jones, 2011). Being impaired in their feelings of fear or remorse, they also have been associated with taking unreasonable organizational risks (Babiak & Hare, 2019; Boddy et al., 2010b) and are more likely to accept direct harm on others (Koenigs et al., 2012). Therefore, in the long run, such psychopaths are considered a substantial organizational risk factor and are associated with a diminished business performance and even several corporate breakdowns (Boddy, 2011, 2017; Sheehy et al., 2021). Given these implications, the topic of corporate psychopathy is increasingly interesting from the perspective of prevention (Lingnau et al., 2017), which involves a variety of interdisciplinary research, including neuroscience, psychology, and law (Sheehy et al., 2021).

The finding that homo economicus is not just morally questionable but resembles a specific form of psychopathy to be found in business is therefore not only conceptually insightful, but it also provides several links to business practice. As shall be argued, the concept of homo economicus is not only a matter of textbook theorems but, if closely considered, the discussed personality aspects reverberate (often unspoken) in institutional settings of businesses, being able to at least partially explain why specific individuals are particularly successful and promoted in these settings. In such vein, to advance in their careers, it is often expected that leaders are tough and decisive, being able to make difficult decisions. Such traits are also particularly reflected in traditional chains of command with their individualized, hierarchical working contexts, which put less emphasis on traits of compassion and emotional closeness. This corresponds with the traditional assumption of an economically rational leadership as discussed by Nicholson and Kurucz (2019). In addition, many working places are undergoing constant changes, facing turbulent environments. Thus, it may be expected of leaders to stay calm and focused. As such, it has been noted that some of the core characteristics of corporate psychopaths, especially those of the affective dimension like cool-mindedness and extreme confidence are often misinterpreted as desirable leadership qualities (Babiak & Hare, 2019; Dutton, 2013; Hill & Scott, 2019). Thus, subclinical psychopaths are often very successful in the hiring process, given their seemingly decisive and strong appearance (Boddy et al., 2021). Furthermore, frequent job changes are common in leadership positions and also to some degree expected. This also provides an excellent setting for corporate psychopaths to employ their manipulative traits as these are often very difficult to detect in the short run (Boddy et al., 2021).

In addition, it could be argued that the modern capitalistic corporation itself is resembling homo economicus. As such, Bakan (2004) argues that the corporation has psychopathic attributes (also see Ketola, 2006). Through the lens of institutional-organizational fit theories that focus on a self-selection of specific individuals into an organization (e.g., Lazear & Rosen, 1981; Ouchi, 1979), it could be explained why corporate psychopaths are especially attracted to business environments. More specifically, many businesses apply material incentives and bonus schemes. Traditionally, these are based on the assumptions of unbounded opportunism (Williamson, 1985), and in specific, the behavioral assumption of the average individual as a potential work averse shirker (Mankiw, 2018), i.e., a manifestation of homo economicus or a corporate psychopath. In such vein, it could be stated with Milgrom and Roberts (1992, p. 42) that these systems are “designed as if people were entirely motivated by narrow, selfish concerns and […] will be fundamentally amoral, ignoring rules, breaking agreements, and employing guile, manipulation, and deception if they see personal gain in doing so.” Even in light of other motives on the side of companies to establish such bonus schemes, individualized material incentives resonate strongly with the selfish and opportunistic traits of corporate psychopaths, given the emphasis on a realization of personal benefit. Thus, they attract corporate psychopaths or the “real homo economicus” (Hoffman, 2011, p. 491). As these considerations show, even if not always made explicit, the model of homo economicus is often reflected in the institutional settings or the “rules of the game” in business.

Implications for Research and Teaching

From these considerations, several implications for research and teaching can be deduced. As a first motivation, given the vast destruction and organizational hazard corporate psychopaths unfold (e.g., Boddy, 2011, 2017), a better understanding of the aforementioned impact of homo economicus would be relevant for the long-term success and organizational resilience of an organization. Besides such, the following considerations can also be motivated from an ethical perspective that is focused on fostering more humane and responsible business practices. To this end, the following discussion will draw on virtue ethics and an ethics of care as two major streams of business ethics (Dawson, 2015; Nicholson & Kurucz, 2019). For virtue ethics, the paper refers to the ethics framework by Slote (1992), who classifies virtuous conduct as comprised of essentially three related major conditions (Dawson, 2015). First, there is the requirement that virtues are not selfish, i.e., they do not exclude others. Second, there is the requirement of an agent/other-balance, i.e., individuals must consider what is good for themselves and good for the other(s), which has to be balanced off. Third, virtuous conduct strives for satisfaction and not maximization. As a corporate psychopath, homo economicus evidently fails on all three criteria. First, homo economicus only cares about the personal benefit and the model’s preferences are thus selfish. There are no genuine trade-offs with regard to the legitimate needs of others and thus these others are, if at all, only considered instrumentally. Last, as already Simon (1983) criticized, homo economicus does not satisfice but maximize. As such, homo economicus is the opposite of a virtuous being. From a second perspective, the model of homo economicus can also be reflected through the lens of an ethics of care, which is provided by Nicholson and Kurucz (2019). In such vein, an ethics of care can be reflected by four facets: a primacy of relationships, complexity in context, a mutual well-being focus, and engaging as a whole person, which includes affective, intuitive, and imaginative aspects. Equally, homo economicus applies an uncaring logic, referred to as the traditional economic rationality paradigm by Nicholson and Kurucz (2019). As such, homo economicus is not interested in maintaining emotionally based relationships. Second, complexity is not addressed by encouragement and moral development but rather by enforcing control as reflected in principal-agent theory (e.g., Picot et al., 2008). Third, genuine mutual well-being is outside the domain of homo economicus. Finally, an empathic, affective engagement with others is irrelevant to homo economicus as there is only economically rational reasoning instead of a comprehensive, caring approach. In conclusion, the psychopathic model implies the opposite of a caring actor. As such, it can be argued that the resemblance of homo economicus in several institutional aspects of many todays’ businesses factually also hampers the realization of more virtuous and caring ethical conduct.

With such in mind, several suggestions shall be made for future research. First of all, hiring practices such as assessment centers should be questioned, as they are barely able to detect corporate psychopaths (Boddy et al., 2021). With regard to virtues, it could be stated that a certain degree of charm, self-confidence, persuasion, visionary thinking, and the ability to sometimes make tough decisions can be desirable from a functional perspective to perform well as a business leader (Dutton, 2013). As such, great leaders show some mild degrees of these traits. However, psychopaths are extreme individuals (Boddy et al., 2015), and no virtuous, balanced individuals that genuinely care for others. Current research is only beginning to deeper investigate into these issues, and specifically with regard to psychopathy, is still largely focused on groundwork conceptual considerations (e.g., Dutton, 2013). Thus, more empirical research is required to find out where such optimum might be situated, or conversely, when the aforementioned traits become dysfunctional.

In addition, it would be generally highly valuable to try to systematically disentangle specific properties of business environments that attract psychopaths, for which this paper could be a starting point. As such, it is important to note that the insight that homo economicus is a corporate psychopath and thus critically to be evaluated from an ethical and psychological perspective, does not render the model worthless. On the contrary, as homo economicus is a corporate psychopath, the model may be of use to identify structures in business that resemble homo economicus and thus currently attract and promote individuals who possess these traits. Based on these considerations, organizational properties could be explored that prevent the ascent of corporate psychopaths. In such way, it might be very interesting to design incentive structures that motivate talented individuals but are less likely to attract psychopathic individuals, for instance, by placing more emphasis on rewarding true social skills (Lingnau et al., 2017; Marshall et al., 2015; Schütte et al., 2018) such as compassionate morality (Woodmass & O’Connor, 2018). These insights could then be linked to system approaches, i.e., the integration and coordination of several approaches that combine and reinforce these effects (Bedford et al., 2016; Grabner & Moers, 2013; Speklé et al., 2022).

Moreover, in general, it seems even more important to think critically about the deeper implications of the values associated with theoretical models used in business that are built on the assumption of economic rationality and thus the maximization of personal benefit. As discussed, even if not explicitly named, the behavioral assumptions of homo economicus are represented in many economic models with regard to “rational” maximization or optimization. Such a critical reflection is especially relevant when these models are applied in real-world contexts such as policy making. For example, neoliberal deregulation and the promotion of shareholder value maximization are based on theoretical assumptions that not only do not hold up in the real world, but often conflict with a societally responsible conduct. Yet, still, political programs and business targets are based on such concepts because it is often not sufficiently considered that the underlying models are only applicable in an abstract, idealized context. This in turn leads to the obviously questionable long-term results in terms of wealth inequality and the erosion of social cohesion, undermining the very foundations of a democratic, free society (e.g., Horváth & Barton, 2016).

In addition to research, academia also has an influence on real-world decision-making via teaching, especially when former students become advisors, decision-makers in firms or policy-makers. Given that the research community has an exemplary function due to prestige and scientific expertise, this leads to think more about the role and responsibility of academic teaching. As stated above, already the choice of model contains some normative basic statements, which are (at least implicitly) conveyed when presented in the classroom. As the classic paper by Frank et al. (1993) as well as some newer research (e.g., Ifcher & Zarghamee, 2018; Kowaleski et al., 2020; Racko, 2019) demonstrates, teaching can influence students’ attitudes, also and in particular with regard to normative aspects. If one considers academic teaching not solely as a means of conveying abstract insights but also as an opportunity to enable future decision-makers to develop their full potentials and capabilities, teaching evidently also has some responsibility. This responsibility toward those being educated would therefore be linked to fostering the development of virtuous and caring personalities such that future decision-makers are able and endeavor to be responsible leaders (Ulrich, 2008). In this light, it can be concluded that a more critical reflection on normative assumptions is also of fundamental importance for teaching. This could include not only a reflection on the psychopathic traits of homo economicus as discussed in this paper, but even more the drawing of a complementary picture with references to other concepts such as homo faber, homo ludens, homo politicus, or homo moralis. These conceptual insights could be enriched with findings from empirical research on human decision-making to broaden the understanding of the real behavioral dispositions of the vast majority of nonpsychopathic individuals or—in Sen’s (1977) notion—to account for homo sapiens as a complex individual that does and should not solely act out of ruthless opportunism but possesses genuine social traits that deserve to be fostered.

Conclusion

As this paper systematically discussed, the concept of homo economicus can be considered a prototype of a psychopath. In contrast to many anecdotal references, this paper took an in-depth analysis delivering a finer picture with regard to the psychological notion of psychopathy. In particular, it could be shown that homo economicus is not simply some kind of psychopath but specifically a subclinical or Factor 1 psychopath, often referred to in business research as a “corporate psychopath.” These are individuals who are extremely callous, selfish, and manipulative, but may appear normal at first glance because they have no significant impairment in their long-term planning and behavioral control, which makes them particularly dangerous in business environments (e.g., Boddy, 2011, 2017).

With such an analysis and establishing a connection to corporate psychopathy, the paper presents a basis for the research community to further and deeper critically reflect on the model of homo economicus. Unquestionably, since its introduction, the model has been intensely debated for a variety of reasons. Concerning the “dark” assumptions on the behavioral side, this paper can enlighten why so many researchers feel some kind of discomfort and critical distance when dealing with this concept—or on the other side of the spectrum—the sometimes perceived necessity to defend the model as solely hypothetical construct. Yet, with regard to the latter, the paper argued that “models matter,” especially when they leave the space of purely theoretical debate and are applied in practice or thought of as sufficient representation of reality.

In light of such real-world consequences of homo economicus, the paper went on to discuss the implications of the conducted psychological analysis for the nexus of academic research and teaching, which were motivated on grounds of an ethics of virtue and care (Ciulla, 2009; Nicholson & Kurucz, 2019). As discussed, homo economicus assumptions, even if unspoken, often reverberate in rational decision-making and the institutional environments of firms, such as in individualistic, competitive environments, and individually oriented, materialistic incentive schemes. As such, this paper can be a starting point to further explore which business settings reflect traits of homo economicus and therefore particularly attract and promote psychopathic individuals. The insights gained should be quite helpful to better protect individuals and society from the dangers unleashed by corporate psychopaths. In this way, a variety of insights from psychology, business, ethics, and law (Sheehy et al., 2021) could be combined to enrich our understanding of the causes and implications of psychopathy in the business context and how preventive measures could be applied against psychopathic organizational misconduct.

Finally, as this paper elaborated, not only research but also teaching should be considered in light of the conducted psychological analysis. Several authors have linked teaching the behavioral assumptions of homo economicus to business scandals and even the last financial crisis with its enormously destructive impact (Giacalone & Wargo, 2009; Melé, 2009; Melé et al., 2011) that also undermined the trust in businesses and the economy at large (e.g., Horváth & Barton, 2016). As such, the findings of this paper are equally relevant with regard to the classroom. Given the insight that teaching always conveys certain basic assumptions, the reflection of what standard economic approaches imply with regard to human values and traits, i.e., in the case of homo economicus, subclinical psychopathy, should also be increasingly considered and discussed. This should be equally important in fostering the rise of more virtuous and caring leaders in future.

Data availability

Not applicable.

References

Acheson, S. K. (2005). Hare psychopathy checklist—revised. In R. A. Spies & B. S. Plake (Eds.), The sixteenth mental measurements yearbook (2nd ed., pp. 429–432). University of Nebraska Press.

Aldred, J. (2009). The skeptical economist: Revealing the ethics inside economics. Routledge.

Anderson, E. (2000). Beyond homo economicus: New developments in theories of social norms. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 29(2), 170–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1088-4963.2000.00170.x

Babiak, P. (2016). Psychopathic manipulation at work. In C. B. Gacono (Ed.), The clinical and forensic assessment of psychopathy: A practitioner’s guide (2nd ed., pp. 353–373). Routledge.

Babiak, P., & Hare, R. D. (2019). Snakes in suits. HarperCollins.

Babiak, P., Neumann, C. S., & Hare, R. D. (2010). Corporate psychopathy: Talking the walk. Behavioral Sciences & The Law, 28(2), 174–193. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.925

Bailey, C. D. (2017). Psychopathy and accounting students’ attitudes towards unethical professional practices. Journal of Accounting Education, 41, 15–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccedu.2017.09.004

Bakan, J. (2004). The corporation: The pathological pursuit of profit and power. Free Press.

Baker, H. K., & Ricciardi, V. (2014). Investor behavior: The psychology of financial planning and investing. Wiley.

Baron, J. (2014). Heuristics and biases. In E. Zamir & D. Teichman (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of behavioral economics and the law (pp. 3–27). Oxford University Press.

Becker, G. S. (1968). Crime and punishment: An economic approach. Journal of Political Economy, 76(2), 169–217. https://doi.org/10.1086/259394

Becker, G. S. (1981). Altruism in the family and selfishness in the market place. Economica, 48(189), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.2307/2552939

Becker, G. S. (1993). A treatise on the family. Harvard University Press.

Bedford, D. S., Malmi, T., & Sandelin, M. (2016). Management control effectiveness and strategy: An empirical analysis of packages and systems. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 51, 12–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2016.04.002

Ben-Ner, A., & Putterman, L. (1998). Values and institutions in economic analysis. In A. Ben-Ner & L. Putterman (Eds.), Economics, values, and organization (pp. 3–69). Cambridge University Press.

Benning, S. D., Venables, N. C., & Hall, J. R. (2018). Succesful psychopathy. In C. J. Patrick (Ed.), Handbook of psychopathy (2nd ed., pp. 585–608). The Guilford Press.

Birchler, U., & Bütler, M. (2007). Information economics. Routledge.

Board, B. J., & Fritzon, K. (2005). Disordered personalities at work. Psychology, Crime & Law, 11(1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160310001634304

Boddy, C. R. P. (2005). The implications of corporate psychopaths for business and society: An initial examination and a call to arms. Australasian Journal of Business and Behavioural Sciences, 1(2), 30–40.

Boddy, C. R. P. (2006). The dark side of management decisions: Organisational psychopaths. Management Decision, 44(10), 1461–1475. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740610715759

Boddy, C. R. P. (2011). The corporate psychopaths theory of the global financial crisis. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(2), 255–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0810-4

Boddy, C. R. P. (2017). Psychopathic leadership a case study of a corporate psychopath CEO. Journal of Business Ethics, 145(1), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2908-6

Boddy, C. R. P. (2023). Is the only rational personality that of the psychopath? Homo economicus as the most serious threat to business ethics globally. Humanistic Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41463-023-00150-y

Boddy, C. R. P., & Taplin, R. (2016). The influence of corporate psychopaths on job satisfaction and its determinants. International Journal of Manpower, 37(6), 965–988. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-12-2015-0199

Boddy, C. R. P., Ladyshewsky, R. K., & Galvin, P. (2010a). Leaders without ethics in global business: Corporate psychopaths. Journal of Public Affairs, 10(3), 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.352

Boddy, C. R. P., Ladyshewsky, R. K., & Galvin, P. (2010b). The influence of corporate psychopaths on corporate social responsibility and organizational commitment to employees. Journal of Business Ethics, 97(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0492-3

Boddy, C. R. P., Miles, D., Sanyal, C., & Hartog, M. (2015). Extreme managers, extreme workplaces: Capitalism, organizations and corporate psychopaths. Organization, 22(4), 530–551. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508415572508

Boddy, C. R. P., Boulter, L., & Fishwick, S. (2021). How so many toxic employees ascend to leadership. In R. A. Örtenblad (Ed.), Debating bad leadership: Reasons and remedies (pp. 69–85). Palgrave Macmillan.

Bolton, G. E., & Ockenfels, A. (2000). ERC: A theory of equity, reciprocity, and competition. American Economic Review, 90(1), 166–193. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.90.1.166

Bolton, G. E., Katok, E., & Ockenfels, A. (2005). Cooperation among strangers with limited information about reputation. Journal of Public Economics, 89(8), 1457–1468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.03.008

Boulding, K. E. (1969). Economics as a moral science. The American Economic Review, 59(1), 1–12.

Boulter, L., & Boddy, C. (2021). Subclinical psychopathy, interpersonal workplace exchanges and moral emotions through the lens of affective events theory (AET). Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 8(1), 44–58. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-12-2019-0120

Brooks, N., Fritzon, K., & Croom, S. (2020). Corporate psychopathy: Entering the paradox and emerging unscathed. In K. Fritzon, N. Brooks, & S. Croom (Eds.), Corporate psychopathy: Investigating destructive personalities in the workplace (pp. 327–365). Palgrave Macmillan.

Brue, S., & Grant, R. (2013). The evolution of economic thought (8th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Ciulla, J. B. (2009). Leadership and the ethics of care. Journal of Business Ethics, 88, 3–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0105-1

Cleckley, H. (1941). The mask of sanity: An attempt to clarify some issues about the so-called psychopathic personality. Mosby.

Cooke, D. J., & Michie, C. (2001). Refining the construct of psychopathy: Towards a hierarchical model. Psychological Assessment, 13(2), 171–188. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.13.2.171

Dash, A. (2019). ‘Good Anthropocene’: The Zeitgeist of the 21st century. In A. K. Nayak (Ed.), Transition strategies for sustainable community systems: Design and systems perspectives (pp. 17–29). Springer.

Davies, W. (2016). The happiness industry: How the government and big business sold us well-being. Verso Books.

Dawson, D. (2015). Two forms of virtue ethics: Two sets of virtuous action in the fire service dispute? Journal of Business Ethics, 128, 585–601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2121-z

Dierksmeier, C. (2011). Reorienting management education: From the homo economicus to human dignity. Humanistic Management Network, Research Paper Series. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1766183

Dixon, W., & Wilson, D. (2012). A history of homo economicus: The nature of the moral in economic theory. Routledge.

Dobuzinskis, L. (2019). Not merely playing game theory’s subversive proclivities. In D. Laycock (Ed.), Political ideology in parties, policy, and civil society: Interdisciplinary insights (pp. 91–111). UBC Press.

Dosi, G., Faillo, M., & Marengo, L. (2021). Beyond “bounded rationality”: Behaviours and learning in complex evolving worlds. In R. Viale (Ed.), Routledge handbook of bounded rationality (pp. 492–505). Routledge.

Dutton, K. (2013). The wisdom of psychopaths. Arrow.

Elster, J. (1989). Social norms and economic theory. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 3(4), 99–117. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.3.4.99

England, P. (2003). Separative and soluble selves: Dichotomous thinking in economics. In A. Ferber & J. A. Nelson (Eds.), Feminist economics today: Beyond economic man (pp. 33–59). The University of Chicago Press.

Falkenbach, D. (2007). Psychopathic traits in juveniles. In D. W. Springer & A. R. Roberts (Eds.), Handbook of forensic mental health with victims and offenders: Assessment, treatment, and research (pp. 225–246). Routledge.

Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2002). Why social preferences matter—the impact of non-selfish motives on competition, cooperation and incentives. The Economic Journal, 112(478), C1–C33. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00027

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (2006). The economics of fairness, reciprocity and altruism—experimental evidence and new theories. In S.-C. Kolm & J. M. Ythier (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of giving, altruism and reciprocity: Foundations (Vol. 1, pp. 615–691). North-Holland.

Fischbacher, U., Gächter, S., & Fehr, E. (2001). Are people conditionally cooperative? Evidence from a public goods experiment. Economics Letters, 71(3), 397–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1765(01)00394-9

Fleming, P. (2017). The death of homo economicus: Work, debt and the myth of endless accumulation. Pluto Press.

Fougère, M., & Solitander, N. (2023). Homo responsabilis as an extension of the neoliberal hidden curriculum: The triple responsibilization of responsible management education. Management Learning, 54(3), 396–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/135050762311626

Frank, R. H., Gilovich, T., & Regan, D. T. (1993). Does studying economics inhibit cooperation? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 7(2), 159–171. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.7.2.159

Fridman, D. (2010). A new mentality for a new economy: Performing the homo economicus in Argentina (1976–83). Economy and Society, 39(2), 271–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085141003620170

Friedland, J., & Cole, B. M. (2019). From homo-economicus to homo-virtus: A system-theoretic model for raising moral self-awareness. Journal of Business Ethics, 155, 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3494-6

Friedman, M. (1976). Essays in positive economics. University of Chicago Press.

Fritzon, K., Bailey, C., Croom, S., & Brooks, N. (2017). Problem personalities in the workplace: Development of the corporate personality inventory. In P. A. Granhag, R. Bull, A. Shaboltas, & E. Dozortseva (Eds.), Psychology and law in Europe: When West meets East (pp. 139–166). CRC Press.

Fritzon, K., Brooks, N., & Croom, S. (2020). Corporate psychopathy: Investigating destructive personalities in the workplace. Springer.

Gächter, S., & Falk, A. (2002). Reputation and reciprocity: Consequences for the labour relation. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 104(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9442.00269

Giacalone, R. A., & Wargo, D. T. (2009). The roots of the global financial crisis are in our business schools. Journal of Business Ethics Education, 6, 147–168. https://doi.org/10.5840/jbee200969

Gigerenzer, G. (2004). Striking a blow for sanity in theories of rationality. In M. Augier & J. G. March (Eds.), Models of a man: Essays in memory of Herbert A. Simon (pp. 389–409). MIT Press.

Gigerenzer, G., & Brighton, H. (2009). Homo heuristicus: Why biased minds make better inferences. Topics in Cognitive Science, 1(1), 107–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-8765.2008.01006.x

Gigerenzer, G., & Gaissmaier, W. (2011). Heuristic decision making. Annual Review of Psychology, 62(1), 451–482. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120709-145346

Gigerenzer, G., & Goldstein, D. G. (2016). Reasoning the fast and frugal way: Models of bounded rationality. In G. Gigerenzer, R. Hertwig, & T. Pachur (Eds.), Heuristics: The foundations of adaptive behavior (pp. 31–57). Oxford University Press.

Gilboa, I. (2012). Rational choice. MIT press.

Gintis, H., & Khurana, R. (2016). Corporate corruption and the failure of business school education. Harvard University.

Glenn, A. L., Iyer, R., Graham, J., Koleva, S., & Haidt, J. (2009). Are all types of morality compromised in psychopathy? Journal of Personality Disorders, 23(4), 384–398. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2009.23.4.384

Grabner, I., & Moers, F. (2013). Management control as a system or a package? Conceptual and empirical issues. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 38(6–7), 407–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2013.09.002

Gregory, D. (2014). Unmasking financial psychopaths: Inside the minds of investors in the twenty-first century. Palgrave Macmillan.

Guzman, A. T. (2008). How international law works: A rational choice theory. Oxford University Press.

Haarjärvi, T., & Laari-Salmela, S. (2022). Site-seeing humanness in organizations. Business Ethics Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2022.12

Hare, R. D. (1980). A research scale for the assessment of psychopathy in criminal populations. Personality and Individual Differences, 1(2), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(80)90028-8

Hare, R. D. (1999). Without conscience: The disturbing world of the psychopaths among us. Guilford Press.

Hare, R. D. (2003). The psychopathy checklist—revised (2nd ed.). Multi-Health Systems.

Hare, R. D., & Neumann, C. S. (2005). Structural models of psychopathy. Current Psychiatry Reports, 7(1), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-005-0026-3

Hare, R. D., & Neumann, C. S. (2008). Psychopathy as a clinical and empirical construct. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4, 217–246. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091452

Harpur, T. J., Hare, R. D., & Hakstian, A. R. (1989). Two-factor conceptualization of psychopathy: Construct validity and assessment implications. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 1(1), 6–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.1.1.6

Hechter, M., & Kanazawa, S. (1997). Sociological rational choice theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 23(1), 191–214. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.23.1.191

Herpertz, S. C., & Sass, H. (2000). Emotional deficiency and psychopathy. Behavioral Sciences & The Law, 18(5), 567–580.

Hervé, H. (2007). Psychopathic subtypes: Historical and contemporary perspectives. In H. Hervé & J. C. Yuille (Eds.), The psychopath: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 431–460). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hill, D., & Scott, H. (2019). Climbing the corporate ladder: Desired leadership skills and successful psychopaths. Journal of Financial Crime, 26(3), 881–896. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-11-2018-0117

Hoffman, M. B. (2011). Evolutionary jurisprudence: The end of the naturalistic fallacy and the beginning of natural reform? In M. Michael (Ed.), Law and neuroscience: Current legal issues (Vol. 13, pp. 483–504). Oxford University Press.

Homans, G. C. (1961). Social behavior: Lts elementary forms. Routledge.

Horváth, D., & Barton, D. (2016). Conclusion: Capitalism re-imagined. In D. Barton, D. Horváth, & M. Kipping (Eds.), Re-imagining capitalism (pp. 319–331). Oxford University Press.

Hühn, M. P., & Dierksmeier, C. (2016). Will the real A. Smith please stand up! Journal of Business Ethics, 136(1), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2506-z

Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. (2015). Personal moral codes and the Hunt-Vitell theory of ethics. In R. A. Peterson & O. C. Ferrell (Eds.), Business ethics: New challenges for business schools and corporate leaders (pp. 18–37). Routledge.

Ifcher, J., & Zarghamee, H. (2018). The rapid evolution of homo economicus: Brief exposure to neoclassical assumptions increases self-interested behavior. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 75, 55–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2018.04.012

Kahneman, D. (2012). Thinking, fast and slow. Penguin Books.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291.

Ketola, T. (2006). From CR-psychopaths to responsible corporations: Waking up the inner sleeping beauty of companies. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 13(2), 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.113

Kirchgässner, G. (2008). Homo oeconomicus: The economic model of behaviour and its applications in economics and other social sciences. Springer.

Koenigs, M., Kruepke, M., Zeier, J., & Newman, J. P. (2012). Utilitarian moral judgment in psychopathy. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 7(6), 708–714. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsr048

Kowaleski, Z. T., Sutherland, A. G., & Vetter, F. W. (2020). Can ethics be taught? Evidence from securities exams and investment adviser misconduct. Journal of Financial Economics, 138(1), 159–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2020.04.008

Lazear, E. P., & Rosen, S. (1981). Rank-order tournaments as optimum labor contracts. Journal of Political Economy, 89(5), 841–864. https://doi.org/10.1086/261010

Levy, D. M. (2002). How the dismal science got its name: Classical economics and the ur-text of racial politics. University of Michigan Press.

Lingnau, V., Fuchs, F., & Dehne-Niemann, T. E. (2017). The influence of psychopathic traits on the acceptance of white-collar crime: Do corporate psychopaths cook the books and misuse the news? Journal of Business Economics, 87(9), 1193–1227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-017-0864-6

Linstead, S. A., & Grafton-Small, R. (1990). Theory as artefact: Artefact as theory. In P. Gagliardi (Ed.), Symbols and artifacts (pp. 387–419). De Gruyter.

Lynam, D. R. (2011). Psychopathy and narcissism. In W. K. Campbell & J. D. Miller (Eds.), The handbook of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder: Theoretical approaches, empirical findings, and treatments (pp. 272–282). Wiley.

Macho-Stadler, I., & Pérez-Castrillo, J. D. (2001). An introduction to the economics of information: Incentives and contracts (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Magni, C. A. (2009). Investment decisions, net present value and bounded rationality. Quantitative Finance, 9(8), 967–979. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697680902849338

Mankiw, N. G. (2018). Principles of microeconomics (8th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Marglin, S. A. (2008). The dismal science: How thinking like an economist undermines community. Harvard University Press.

Marshall, A. J., Baden, D., & Guidi, M. (2013). Can an ethical revival of prudence within prudential regulation tackle corporate psychopathy? Journal of Business Ethics, 117(3), 559–568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1547-4

Marshall, A. J., Ashleigh, M. J., Baden, D., Ojiako, U., & Guidi, M. G. (2015). Corporate psychopathy: Can ‘search and destroy’ and ‘hearts and minds’ military metaphors inspire HRM solutions? Journal of Business Ethics, 128(3), 495–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2117-8

Martinás, K. (2010). Complexity and the role of interactions. In K. Martinás, D. Matika, & A. Srbljinović (Eds.), Complex societal dynamics: Security challenges and opportunities (pp. 65–79). IOS Press.

Mathieu, C., & Babiak, P. (2016). Corporate psychopathy and abusive supervision: Their influence on employees’ job satisfaction and turnover intentions. Personality and Individual Differences, 91, 102–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.12.002

Melé, D. (2009). Editorial introduction: Towards a more humanistic management. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(3), 413–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0129-6

Melé, D., & Cantón, C. G. (2014). Human foundations of management: Understanding the homo humanus. Palgrave Macmillan.

Melé, D., Argandoña, A., & Sanchez-Runde, C. (2011). Facing the crisis: Toward a new humanistic synthesis for business. Journal of Business Ethics, 99(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0743-y

Mell, A., & Walker, W. (2014). The rough guide to economics. Rough Guides.

Merchant, K. A., & Van der Stede, W. A. (2017). Management control systems: Performance measurement, evaluation and incentives. Pearson.

Milgrom, P. R., & Roberts, J. (1992). Economics, organization and management. Prentice Hall.

Mill, J. S. (1844). On the definition of political economy; and on the method of investigation proper to it. In J. S. Mill (Ed.), Essays on some unsettled questions of political economy (pp. 120–164). John W. Parker.

Miller, J. D., Back, M. D., Lynam, D. R., & Wright, A. G. (2021). Narcissism today: What we know and what we need to learn. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 30(6), 519–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/09637214211044109

Morse, G. (2004). Executive psychopaths. Harvard Business Review, 82(10), 20–22.

Murray, A. A., Wood, J. M., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2012). Psychopathic personality traits and cognitive dissonance: Individual differences in attitude change. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(5), 525–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2012.05.011

Myung, J. K., Choi, Y. H., & Kim, J. D. (2017). Effects of CEOs’ negative traits on corporate social responsibility. Sustainability, 9(4), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040543

Nelson, J. A. (1993). Gender and economic ideologies. Review of Social Economy, 51(3), 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/758537259

Nicholson, J., & Kurucz, E. (2019). Relational leadership for sustainability: Building an ethical framework from the moral theory of ‘ethics of care.’ Journal of Business Ethics, 156, 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3593-4

Ogaki, M., & Tanaka, S. C. (2019). Normative behavioral economics: Toward a new economics by integration with traditional economics. Springer.

Ong, M., Cunningham, J. L., & Parmar, B. L. (2022). Lay beliefs about homo economicus: How and why does economics education make us see honesty as effortful? Academy of Management Learning & Education. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2021.0134

Ostapiuk, A. (2021). The eclipse of value-free economics: The concept of multiple self versus homo economicus. Wroclaw University Press.

Ouchi, W. G. (1979). A conceptual framework for the design of organizational control mechanisms. Management Science, 25(9), 833–848. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.25.9.833

Parkin, M. (2014). Microeconomics (11th ed.). Pearson.

Parsons, S. (2005). Rational choice and politics. Continuum.

Patrick, C. J. (2018). Psychopathy as masked pathology. In C. J. Patrick (Ed.), Handbook of psychopathy (2nd ed., pp. 3–21). The Guilford Press.

Pearlstein, S. (2016). Challenging the greed-is-good gospel of free markets. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/challenging-the-greed-is-good-gospel-of-free-markets/2016/06/02/dc924566-1e8e-11e6-b6e0-c53b7ef63b45_story.html.

Perri, F. S. (2013). Visionaries or false prophets. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 29(3), 331–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043986213496008

Persky, J. (1995). The ethology of homo economicus. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(2), 221–231. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.9.2.221

Picot, A., Reichwald, R., & Wigand, R. (2008). Information, organization, and management. Springer.

Pindyck, R. S., & Rubinfeld, D. L. (2018). Microeconomics (9th ed.). Pearson.

Racko, G. (2019). The values of economics. Journal of Business Ethics, 154, 35–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3442-5

Ray, J. V., & Jones, S. (2011). Self-reported psychopathic traits and their relation to intentions to engage in environmental offending. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 55(3), 370–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X10361582

Schütte, N., Blickle, G., Frieder, R. E., Wihler, A., Schnitzler, F., Heupel, J., & Zettler, I. (2018). The role of interpersonal influence in counterbalancing psychopathic personality trait facets at work. Journal of Management, 44(4), 1338–1368. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315607967

Sen, A. K. (1977). Rational fools: A critique of the behavioral foundations of economic theory. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 6(4), 317–344.

Sheehy, B., Boddy, C., & Murphy, B. (2021). Corporate law and corporate psychopaths. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 28(4), 479–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2020.1795000

Siebenhüner, B. (2000). Homo sustinens–towards a new conception of humans for the science of sustainability. Ecological Economics, 32(1), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00111-1

Simon, H. A. (1983). Reason in human affairs. Stanford University Press.

Slote, M. (1992). From morality to virtue. Oxford University Press.

Smith, A. (1761). The theory of moral sentiments (2nd ed.). A. Millar.

Smith, A. (1804). An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations (4th ed., Vol. 1). Oliver D. Cooke.

Smith, E., & Foley, D. K. (2008). Classical thermodynamics and economic general equilibrium theory. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 32(1), 7–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jedc.2007.01.020

Speklé, R. F., Verbeeten, F. H., & Widener, S. K. (2022). Nondyadic control systems and effort direction effectiveness: Evidence from the public sector. Management Accounting Research, 54, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2021.100769

Stevens, G. W., Deuling, J. K., & Armenakis, A. A. (2012). Successful psychopaths: Are they unethical decision-makers and why? Journal of Business Ethics, 105(2), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0963-1

Stout, M. (2005). The ice people. Psychology Today, 38(1), 72–76.

Stout, L. A. (2012). The shareholder value myth: How putting shareholders first harms investors, corporations, and the public. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Stout, L. A. (2014). Law and prosocial behavior. In E. Zamir & D. Teichman (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of behavioral economics and the law (pp. 195–212). Oxford University Press.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131.

Ulrich, P. (2008). Integrative economic ethics: Foundations of a civilized market economy. Cambridge University Press.

Valentine, S., Fleischman, G., & Godkin, L. (2018). Villains, victims, and verisimilitudes: An exploratory study of unethical corporate values, bullying experiences, psychopathy, and selling professionals’ ethical reasoning. Journal of Business Ethics, 148, 135–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2993-6

Van Scotter, J. R., & De DéaRoglio, K. (2020). CEO bright and dark personality: Effects on ethical misconduct. Journal of Business Ethics, 164(3), 451–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4061-5

Verburg, R. (2018). Greed, self interest and the shaping of modern economics. Routledge.

Waddock, S. (2020). Will businesses and business schools meet the grand challenges of the era? Sustainability, 12(15), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156083

Weber, S., Habel, U., Amunts, K., & Schneider, F. (2008). Structural brain abnormalities in psychopaths—a review. Behavioral Sciences & The Law, 26(1), 7–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.802

Williamson, O. E. (1985). The economic intstitutions of capitalism: Firms, markets, relational contracting. Free Press.