Abstract

The aims of this study were to assess the mediating role of household socioeconomic position (SEP) in the associations between the country-level factors: family social benefits, and public income support to single parent households (SPH), with the individual-level factor adolescent life satisfaction. Our sample consisted of adolescent (11, 13, and 15 years old) participants in the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study (2013/2014) across Canada and 24 countries in Europe. We used World Bank data on country wealth from OECD data on social benefits for families and public income support to SPH. Multilevel linear regressions assessed mediated (indirect) associations of these country-level predictors, through SEP, with life satisfaction. Family social benefits ranged between 1.1% and 3.7% of country wealth. The direct association showed that family social benefits were associated with lower adolescent life satisfaction (β = -0.244, 95% Confidence Intervals [C.I.] = -0.306, -0.182, p < 0.0001) among all adolescents and for adolescents in SPH (β = -0.118, 95% C.I. = -0.161, -0.074, p < 0.0001). However, the mediated (indirect) association showed that family social benefits were associated with higher life satisfaction which is partially mediated by SEP (β = 0.087, 95% C.I. = 0.065, 0.109, p < 0.0001) among all adolescents and for adolescents in SPH as well (β = 0.041, 95% C.I. = 0.030, 0.052, p < 0.0001). Country policies may support the wellbeing of adolescents by reducing poverty and improving their socioeconomic position in society.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Globally, 1.2 billion children live in poverty, with hundreds of millions living in multidimensional poverty; these numbers increased during the COVID-19 pandemic (UNICEF, 2021). Family social benefits improve the well-being of families by lifting families out of poverty and reducing societal inequalities (Ahrendt et al., 2016; Gauthier, 2002). Families eligible for these benefits face adverse social and living conditions as they live in poverty or are at-risk-of-poverty. Families with children and adolescents are at a higher risk of poverty than the rest of the population (Ahrendt et al., 2016). This is of concern since child poverty increases the risk of social and health disadvantages such as poor physical and mental health, low educational attainment, and mortality in early and later life (Dyson et al., 2009; Pearce et al., 2019; Richardson, 2010). These socioeconomic inequalities in health persist throughout adulthood, and from one generation to the next (Hossin et al., 2020).

Cross-sectional and longitudinal investigations found that adolescents living with lower socioeconomic position (SEP) have lower well-being than their more affluent peers in (Chzhen et al., 2016; Elgar et al., 2015; Elgar, Gariépy, et al., 2017; Elgar, Xie, et al., 2017; Eryilmaz, 2010; Pearce et al., 2019). In a study of adolescents in Canada and European countries participating in the Health Behaviour for School-aged Children study (HBSC) in 2013/2014, adolescents living in higher SEP families reported higher life satisfaction than their peers in lower SEP groups (Zaborskis & Grincaite, 2018). In a survey of adolescents in Canada, higher SEP was associated with happiness as those living with more material deprivation scored lower on a happiness scale (Burton & Phipps, 2008).

In the context of the Self-Determination Theory, low SEP deprives youth from opportunities and marginalises them from experiences that foster their adjustment, social integration, and growth (Ryan, 1995; Vansteenkiste et al., 2020). Therefore, youth’s psychological wellbeing has social determinants that include SEP and income inequality (Di Domenico & Fournier, 2014; González et al., 2016; Vansteenkiste et al., 2020).

Investigating these factors is in line with a multidimensional understanding of deprivation which rather than solely focusing on low monetary resources as it also takes into consideration social factors that enrich a person’s standard of living (Bárcena-Martín et al., 2017). For example, UNICEF’s Multiple Overlapping Deprivation Analysis (MODA) has facilitated research and surveillance of youth who are multidimensionally poor. Rather than focus on income poverty, this approach puts a greater emphasis on overlapping dimensions of poverty (e.g., having poor access to education, safe communities, health services, and government policies and in-kind benefits that support families; Chzhen et al., 2018; De Neubourg et al., 2012)).

The evidence also indicates that differences in family structure contributes to health and social disadvantage. Among all family configurations, single parent households (SPH) have the most difficulty making ends meet (Ahrendt et al., 2016). Also, adolescents in SPH experience lower life satisfaction than their counterparts in two-parent households even after differences in SEP are controlled (Levin & Currie, 2010). Some countries grant public income support to SPH as cash benefits, in addition to family social benefit that is dedicated to all families. A study in Japan found that adolescents in SPH who receive family social benefits had a higher prevalence of chronic diseases (asthma, allergic rhinitis, dermatitis, and eczema) than adolescents in non-SPH (Nishioka et al., 2021). The authors suggest that families who need assistance are at a social disadvantage which in turn is associated with poorer health outcomes; these are the families who are receiving the social benefit (Nishioka et al., 2021).

In contrast, adolescents living in households with higher SEP and with two parents were associated with higher life satisfaction among a cross-national survey of adolescents in the HBSC study, relative to adolescents in lower SEP and non-SPH families, respectively (Zaborskis et al., 2019). Family dynamics (such as having a comfortable home, stability, and open communication at home) were associated with higher wellbeing among youth (Joronen & Åstedt-Kurki, 2005; Rask et al., 2003). Evidence from these studies suggests that adolescents who live in low SEP families and in SPH are at a further social and health disadvantage than their peers in more affluent and non-SPH households, respectively.

Several studies report that macroeconomic conditions (e.g., country wealth, unemployment, social protection benefits) play a role in household deprivation status (Bárcena-Martín et al., 2017; Figari, 2012). A cross-national study across Europe found that macroeconomic conditions account for half of the variation in child deprivation, after controlling for individual determinants (Bárcena-Martín et al., 2017). Furthermore, family social benefits reportedly alleviate some of the financial burden among disadvantaged families (Ahrendt et al., 2016). They are also associated with lower childhood poverty rates in Europe (Bárcena-Martín et al., 2017; Nygård et al., 2019). After the 2008 financial crisis, Chzhen (2017) reported that European children were less likely to be poor in countries that dedicated more social protection spending from 2008 to 2013. These results suggest that additional social assistance to families improves living conditions of disadvantaged families and reduces child poverty (Chzhen, 2017). Reducing the health impacts of low SEP requires reductions in socioeconomic inequality in society (Krueger et al., 2015; Wilkinson & Pickett, 2006). In adults, public social benefits that protect against market risk relate to higher life satisfaction (Jakubow, 2014). However, the benefits to adolescents are unclear.

Other research suggests that social benefits improve adolescent health and development through intermediatory pathways such as better access to health services, greater food consumption and security, and better sexual and reproductive health (de Walque et al., 2017). For example, an investigation from countries in the European Union found that every $100 increase in social spending was associated with 1.19% drop in all cause mortality from diseases, while increases in healthcare spending were not (Stuckler et al., 2010). The association between public benefits with social and health conditions may differ depending on the benefit’s goals, design, and delivery (de Walque et al., 2017; Krueger et al., 2015). Evidence on intermediatory pathways in the relationship between social benefits and adolescent health is lacking.

As such, the aims of this study were to assess the mediating role of household SEP in the association between family social benefits and life satisfaction in adolescents as well as the mediating role of household SEP between and public income support provided to SPH and life satisfaction among adolescents in SPH. We hypothesized that the country-level family social benefits and income support to SPH relate to better life satisfaction in adolescents through increased household SEP.

2 Methods

2.1 Sample

Participants consisted of adolescents (11, 13, and 15 years old) taking part in the 2013/2014 Health Behaviour for School-aged Children (HBSC) study in 25 countries, including Canada and Europe. Nationally representative samples provided information regarding their family affluence, health behaviours, health, and life satisfaction in self-reported surveys conducted during schooltime in their classrooms. Ethics approval was obtained from national regulatory bodies as per an international protocol (Inchley et al., 2016, 2020). Respective approvals by schools, school boards, and other authorities ensured survey administration was appropriate.

Cluster sampling was used where the primary sampling unit was the school class; when not possible, schools were the primary sampling units. All students within the class were included. Informed consent was sought from parents/guardians and passive, informed consent sought from adolescents. Response rates were over 60% in most countries and regions (Inchley et al., 2016). To align with the country-level variables, we combined HBSC’s national samples from French and Flemish regions of Belgium and from England, Wales, and Scotland in the United Kingdom.

3 Measures

3.1 Individual-level variables

3.1.1 Household socioeconomic position

Household SEP was measured using the HBSC Family Affluence Scale. This scale is a 6-item measure of common material assets in the home (Currie et al., 2008): “Do you have your own bedroom for yourself?”, “How many bathrooms are in your home?”, “Does your family own a car, van or truck?”, “How many times did you and your family travel out of your country for a holiday last year?”, “Does your family have a dishwasher at home?” and “How many computers does your family own?”. We constructed an index of material deprivation by transforming the total score to weighted ranks, and then reversed the index so it ranged from 0 (least deprived) to 1 (most deprived) with a mean of 0.5 (Elgar et al., 2017a, b).

3.1.2 Self-reported life satisfaction

Life satisfaction was measured with the Cantril analog scale (1965). This scale asks adolescents to rate “In general, where on the ladder do you feel you stand at the moment?” ranging from 0 (worst possible life) to 10 (best possible life) while being presented with an image of a ladder. The scale is valid for use among adults and adolescents (Cantril, 1965; Levin & Currie, 2014).

3.2 Country-level variables

For country wealth, we used national gross domestic product (GDP) per capita [in United States Dollars (USD)], provided by the World Bank from 2014 (The World Bank, 2014). As for family social benefits, two measures were included. The first is family social benefits in percent of country wealth as collected from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 2014. In this study, we will refer to this measure as “family social benefits”. It encompasses public spending on families in the following categories: cash-related transfers, public spending on services (e.g., subsidizing childcare), and financial support through the tax system and is measured as a percent of country wealth (Organization for Economic Co-operation & Development, 2020b). The second measure is public income support provided to single parent households (SPH) in thousands of USD as collected from the family cash benefits database from OECD in 2014 (Organization for Economic Co-operation & Development, 2020a). In this study, we refer to this measure as “public income support to SPH”. The benefits encompass several family cash benefits; our analysis only included single-parent household benefits and is reported per child, in USD.

3.3 Statistical analyses

We present country-level, summary statistics for adolescent characteristics, country wealth, and country social assistance. We then display in figures each country’s position as a function of the average household SEP and adolescent life satisfaction with country social assistance. Next, our adjusted, multilevel, linear, regression models assessed the association between life satisfaction (dependent variable) and household SEP, social benefits for families, and public income support provided to single-parent households while controlling for age and gender. To assess the role of household SEP as a mediating factor between country social assistance and adolescent life satisfaction (dependent variable), two multilevel, mediation analyses were investigated. The first assessed whether household SEP plays a mediating role in the association between family social benefits and adolescent life satisfaction. The second assessed whether household SEP plays a mediating role in the association between public income support to SPH and adolescent life satisfaction. The latter mediation analysis was only conducted on the population of adolescents living in SPH. Statistical significance was considered at 5%. All analyses were conducted in Stata (Stata Press, 2019), except for the mediation analyses which were conducted in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2018).

4 Results

Table 1 displays the country-level averages for adolescents’ age, household SEP, and life satisfaction; as well as, the country-level variables country wealth, family social benefits, and public income support to SPH, for each country. Adolescents were, on average, 13.6 years old, had an SEP of 0.46 (on a scale of 0 to 1, with 1 indicating the highest household material deprivation), and reported a life satisfaction of 7.58 out of 11. Average country wealth per capita was 31,296.9 USD (Standard deviation [S.D.] = 9604.2). From country wealth, 2.58% (S.D. = 0.88) was used as social benefits for families, while supplemented SPH were about 1908.7 USD (S.D. = 1597.9) per child. As for adolescents in SPH (15.7%), they reported more deprivation (SEP mean = 0.58, S.D. = 0.27) relative to adolescents in non-SPH (mean = 0.48, S.D. = 0.28).

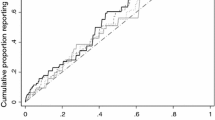

Figure 1 shows the associations at the country level between household SEP and family social benefits in Figure (a), between household SEP and public income support to SPH in Fig. 1c, between life satisfaction and family social benefits in Figure (b), and between life satisfaction and public income support to SPH in Fig. 1d. Figuresa and c show that in countries with higher family social benefits, adolescents reported lower deprivation among all adolescents (r = -0.37, p < 0.0001), and adolescents in SPH (r = -0.46, p < 0.0001), respectively. As for life satisfaction, figures (b) and (d) show that in countries with higher family social benefits, adolescents reported lower life satisfaction among all adolescents (r = -0.25, p < 0.0001), while a weak association was detected among adolescents’ life satisfaction and public income support to SPH among adolescents living in SPH (r = 0.058, p < 0.0001).

Table 2 shows results from the multilevel models that investigated the association between life satisfaction with household SEP and family social benefits among the general population (Models 1 and 2) and among SPH only (Models 3 and 4). Low household SEP is associated with lower life satisfaction scores across the four models. Family social benefits was not significantly associated with life satisfaction in the models (as the confidence intervals spans zero) neither among the general population, nor among adolescents in SPH.

Figure 2 shows the mediated path analysis which assessed whether there was an association between life satisfaction and family social benefits mediated via household SEP. Although it may seem like family social benefits is associated with lower life satisfaction (direct effect = -0.244, 95% C.I. = -0.306, -0.182, p < 0.0001), family social benefits was associated with higher life satisfaction (indirect effect = 0.087, 95% C.I. = 0.065, 0.109, p < 0.0001) when the relationship was adjusted for household SEP via a mediating pathway.

Multilevel mediation analysis for family social benefits, controlling for country wealth. A box in blue shading indicates a country-level measure; a box in yellow shading indicates an individual-level measure. Results: Direct effect = a = -0.931*** (-1.016, -0.846). Direct effect = b = -0.094*** (-0.116, -0.071). Direct effect = c = -0.244*** (-0.306, -0.182). Indirect effect = a*b = 0.087*** (0.065, 0.109). Total effect = a*b + c = -0.157*** (-0.207, -0.106)

Figure 3 shows the mediated path analysis, among adolescents in SPH only, which assesses whether there is an association between life satisfaction and public income support to SPH (in USD, per child) that is mediated via household SEP. Although it may seem like public income support to SPH is associated with lower life satisfaction (direct effect = -0.118, 95% C.I. = -0.161, -0.074, p < 0.0001), public income support to SPH is associated with higher life satisfaction (indirect effect = 0.041, 95% C.I. = 0.030, 0.052, p < 0.0001) when the relationship is adjusted for household SEP via a mediating pathway.

Multilevel mediation analysis for public income support to SPH, controlling for country wealth. A box in blue shading indicates a country-level measure; a box in yellow shading indicates an individual-level measure. Results: Direct effect = a = -0.049*** (-0.060, -0.039). Direct effect = b = -0.828*** (-0.719, -0.938). Direct effect = c = -0.118*** (-0.161, -0.074). Indirect effect = a*b = 0.041*** (0.03, 0.052). Total effect = a*b + c = -0.077** (-0.118, -0.035)

5 Discussion

Our multinational investigation found that family social benefits are associated with a higher life satisfaction among adolescents via the mediating association with household SEP. Public income support to SPH are also associated with higher life satisfaction among adolescents via the mediating association with household SEP.

Our findings bridge the literature on family social benefits and household SEP with the literature on household SEP and adolescent life satisfaction. Previous studies establish that adolescents living in higher SEP conditions report higher life satisfaction (Chzhen et al., 2016; Elgar et al., 2015; Elgar, Gariépy, et al., 2017; Elgar, Xie, et al., 2017; Pearce et al., 2019; Zaborskis & Grincaite, 2018; Zaborskis et al., 2019). Previous literature also reports that family social benefits contribute to alleviating household deprivation (Ahrendt et al., 2016; Bárcena-Martín et al., 2017; Nygård et al., 2019) and that additional social assistance can alleviate household deprivation in certain circumstances such as financial crises and extreme financial difficulties (Chzhen, 2017). Socially-disadvantaged families (such as SPH) report lower SEP (Ahrendt et al., 2016) and adolescents in these families report poorer health (Nishioka et al., 2021); thus, these are a group of youth that warrant special attention. In-line with other research on adults (and that use different measures), we find that intermediatory pathways bridge the gap between public benefits and health outcomes among adolescents (de Walque et al., 2017; Stuckler et al., 2010).

These findings can be interpreted using several theoretical models. The family stress model suggests that among families with higher SEP, the physical and mental health of the members of a family are better because there are more household resources (de Walque et al., 2017; Mistry et al., 2004). The family investment model builds upon the family stress model and suggests that families with higher SEP have more money to spend on inputs and more time to spend with adolescents which together will enhance their mental health by familial social support and the presence of material assets (Bauer et al., 2021; de Walque et al., 2017; Del Boca et al., 2014; Duleep, 2018). The findings are also consistent with Self-Determination Theory (Ryan, 1995; Vansteenkiste et al., 2020). We found that youth’s basic psychological needs are not restricted to individual factors but rather also have contextual predictors at the macro-level which include household SEP and family social benefits.

Although country wealth is a robust determinant of adolescent health, this study found that wealth which is distributed through social welfare and social benefits play important roles as well. Previous research places more importance on social benefits than country wealth as Stuckler et al., found that a rise in social welfare spending was associated with a greater reduction in all-cause mortality compared to increasing a country’s wealth (GDP) by the same amount (Stuckler et al., 2010). As such, there is value in including social benefits in future adolescent health research and for future research to investigate returns on investments in social benefits.

Social benefits and income support to families have different impacts across levels of household income. The same amount of income support (e.g., 2000 USD) will have greater health and social returns for families with incomes of 30,000 USD versus 100,000 USD (McEwen & Stewart, 2014). Other factors that play a role in assessing social benefits are diminishing marginal returns and threshold effects. Diminishing marginal returns suggests that each additional dollar has a lower impact on social and health outcomes than the previous dollar; thus, estimating the sum that maximizes social and health benefits is important (Dooley & Stewart, 2007). There may also be a threshold effect, where there is a level of income beyond which income support no longer contributes to better health. Previous research from 2004 in Canada estimated it at 60,000 (Canadian Dollars) but the threshold level may very well have changed since then (Dooley & Stewart, 2004).

Although it is important to invest in child-centered policies (Richardson, 2010), investing in family-centered policies is paramount and will also contribute to alleviating child poverty (Bárcena-Martín et al., 2017; Pearce et al., 2019). Improving the social conditions in which people live by providing public services, employment opportunities, healthcare, and support to the most vulnerable will ensure healthier societies. Although our study only investigated income support, the provision of other services also helps alleviate child poverty and reduce socioeconomic inequalities in education, healthcare, and public transport (Marmot et al., 2013).

Our study is a multinational investigation of the association between family social benefits and adolescents’ life satisfaction via the mediated role of household SEP in 25 countries in Europe and Canada. Our study uses a large sample of adolescents in multilevel regression and mediation analyses that account for the nested nature of the data and account for the mediated role of SEP in the association between family social benefits and adolescent life satisfaction. As for limitations of this study, this is a cross-sectional study that investigates associations; thus, causal inferences cannot be made from these findings. Additionally, social assistance programs have different designs, objectives, and contexts; thus, our results cannot be generalization to all social assistance programs. Rather, they are limited to family social benefits and SPH. We also recommend future studies that address youth living in other locations such as the East and the Global South.

In conclusion, family social benefits are associated with higher life satisfaction among adolescents via the mediated association with household SEP among adolescents participating in the HBSC survey across Europe and Canada in 2013/2014. Research methods that take into consideration mediated associations at the household level are likely to mediate other associations between public policies and individual health outcomes.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due restrictions on sharing the data.

Code availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due restrictions on sharing the code.

References

Ahrendt, D., Blum, S., & Crepaldi, C. (2016). Families in the Economic Crisis: Changes in Policy Measures in the EU Coordinating. https://doi.org/10.2806/171730

Bárcena-Martín, E., Blázquez, M., Budría, S., & Moro-Egido, A. I. (2017). Child deprivation and social benefits: Europe in cross-national perspective. Socio-Economic Review. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwx019

Bauer, A., Stevens, M., Purtscheller, D., Knapp, M., Fonagy, P., Evans-Lacko, S., & Paul, J. (2021). Mobilising social support to improve mental health for children and adolescents: A systematic review using principles of realist synthesis. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251750

Burton, P., & Phipps, S. (2008). Economic Resources, Relative Socioeconomic Position and Social Relationships: Correlates of the Happiness of Young Canadian Teens. Child Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-008-9014-6

Cantril, H. (1965). The pattern of human concern. Rutgers University Press.

Chzhen, Y. (2017). Unemployment, social protection spending and child poverty in the European Union during the Great Recession. Journal of European Social Policy. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928716676549

Chzhen, Y., Bruckauf, Z., Toczydlowska, E., Elgar, F. J., Moreno-Maldonado, C., Stevens, G. W. J. M., Sigmundová, D., & Gariépy, G. (2018). Multidimensional Poverty Among Adolescents in 38 Countries: Evidence from the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) 2013/14 Study. Child Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-017-9489-0

Chzhen, Y., Moor, I., Pickett, W., Stevens, E., & Stevens, G. (2016). Family Affluence and Inequality in Adolescent Health and Life Satisfaction: Evidence from the HBSC study 2002–2014. Innocenti Working Paper No.2016–10

Currie, C., Molcho, M., Boyce, W., Holstein, B., Torsheim, T., & Richter, M. (2008). Researching health inequalities in adolescents: The development of the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Family Affluence Scale. Social Science and Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.024

De Neubourg, C., Chai, J., De Milliano, M., Plavgo, I., & Wei, Z. (2012). Step-by-Step Guidelines to the Multiple Overlapping Deprivation Analysis (MODA). https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/iwp_2012_10.pdf

de Walque, D., Fernald, L., Gertler, P., & Hidrobo, M. (2017). Cash Transfers and Child and Adolescent Development. In Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition (Volume 8): Child and Adolescent Health and Development. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0423-6_ch23

Del Boca, D., Flinn, C., & Wiswall, M. (2014). Household choices and child development. Review of Economic Studies. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdt026

Di Domenico, S. I., & Fournier, M. A. (2014). Socioeconomic Status, Income Inequality, and Health Complaints: A Basic Psychological Needs Perspective. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0572-8

Dooley, M., & Stewart, J. (2004). Family income and child outcomes in Canada. Canadian Journal of Economics. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0008-4085.2004.00253.x

Dooley, M., & Stewart, J. (2007). Family income, parenting styles and child behavioural-emotional outcomes. Health Economics. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1142

Duleep, H. O. (2018). The family investment model: A formalization and review of evidence from across immigrant groups. In Immigrant Women. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351320603-4

Dyson, A., Hertzman, C., Roberts, H., Tunstill, J., & Vaghri, Z. (2009). Childhood development, education and health inequalities.

Elgar, F. J., Gariépy, G., Torsheim, T., & Currie, C. (2017a). Early-life income inequality and adolescent health and well-being. Social Science and Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.10.014

Elgar, F. J., Pförtner, T. K., Moor, I., De Clercq, B., Stevens, G. W. J. M., & Currie, C. (2015). Socioeconomic inequalities in adolescent health 2002–2010: A time-series analysis of 34 countries participating in the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study. The Lancet. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61460-4

Elgar, F. J., Xie, A., Pförtner, T.-K., White, J., & Pickett, K. E. (2017b). Assessing the View From Bottom: How to Measure Socioeconomic Position and Relative Deprivation in Adolescents. In Assessing the View From Bottom: How to Measure Socioeconomic Position and Relative Deprivation in Adolescents. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526406347

Eryilmaz, A. (2010). Turkish adolescents’ subjective well-being with respect to age, gender and SES of parents. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology. 10.5281/zenodo.1328626

Figari, F. (2012). Cross-national differences in determinants of multiple deprivation in Europe. Journal of Economic Inequality. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-010-9157-9

Gauthier, A. H. (2002). Family policies in industrialized countries: Is there convergence? Population. https://doi.org/10.2307/3246635

González, M. G., Swanson, D. P., Lynch, M., & Williams, G. C. (2016). Testing satisfaction of basic psychological needs as a mediator of the relationship between socioeconomic status and physical and mental health. Journal of Health Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105314543962

Hossin, M. Z., Björk, J., & Koupil, I. (2020). Early-life social and health determinants of adult socioeconomic position: Associations and trends across generations. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2019-213209

Inchley, J., Currie, D., Budisavljevic, S., Torsheim, T., Jåstad, A., Cosma, A., Kelly, C., & Arnarsson, Á. M. (2020). Spotlight on adolescent health and well-being: Findings from the 2017/2018 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey in Europe and Canada. http://www.hbsc.org/publications/international/

Inchley, J., Currie, D., Young, T., Samdal, O., Torsheim, T., Augustson, L., Mathison, F., Aleman-Diaz, A., Molcho, M., Weber, M., & Barnekow, V. (2016). Growing up unequal: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study: International report from the 2013/2014 survey. Health Policy for Children and Adolescents.

Jakubow, A. (2014). State intervention and life satisfaction reconsidered: The role of governance quality and resource misallocation. Politics and Policy. https://doi.org/10.1111/polp.12057

Joronen, K., & Åstedt-Kurki, P. (2005). Familial contribution to adolescent subjective well-being. International Journal of Nursing Practice. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2005.00509.x

Krueger, P. M., Dovel, K., & Denney, J. T. (2015). Democracy and self-rated health across 67 countries: A multilevel analysis. Social Science and Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.047

Levin, K. A., & Currie, C. (2010). Family structure, mother-child communication, father-child communication, and adolescent life satisfaction: A cross-sectional multilevel analysis. Health Education. https://doi.org/10.1108/09654281011038831

Levin, K. A., & Currie, C. (2014). Reliability and Validity of an Adapted Version of the Cantril Ladder for Use with Adolescent Samples. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0507-4

Marmot, M., Bloomer, E., & Goldblatt, P. (2013). The role of social determinants in tackling health objectives in a context of economic crisis. Public Health Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03391694

McEwen, A., & Stewart, J. M. (2014). The relationship between income and children’s outcomes: A synthesis of Canadian evidence. Canadian Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.3138/cpp.40.1-SYN

Mistry, R. S., Biesanz, J. C., Taylor, L. C., Burchinal, M., & Cox, M. J. (2004). Family income and its relation to preschool children’s adjustment for families in the NICHD study of early child care. Developmental Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.40.5.727

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. (2018). Mplus (8.2). https://www.statmodel.com/

Nishioka, D., Saito, J., Ueno, K., & Kondo, N. (2021). Single-parenthood and health conditions among children receiving public assistance in Japan: A cohort study. BMC Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-02682-4

Nygård, M., Lindberg, M., Nyqvist, F., & Härtull, C. (2019). The Role of Cash Benefit and In-Kind Benefit Spending for Child Poverty in Times of Austerity: An Analysis of 22 European Countries 2006–2015. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02126-8

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2020a). Family cash benefits. OECD Family Database. https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/PF1_3_Family_Cash_Benefits.pdf

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2020b). Public spending on family benefits. OECD Family Database. https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/PF1_1_Public_spending_on_family_benefits.pdf

Pearce, A., Dundas, R., Whitehead, M., & Taylor-Robinson, D. (2019). Pathways to inequalities in child health. Archives of Disease in Childhood. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2018-314808

Rask, K., Åstedt-Kurki, P., Paavilainen, E., & Laippala, P. (2003). Adolescent subjective well-being and family dynamics. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-6712.2003.00118.x

Richardson, D. (2010). Child and Family Policies in a Time of Economic Crisis. In Children and Society. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2010.00334.x

Ryan, R. M. (1995). Psychological Needs and the Facilitation of Integrative Processes. Journal of Personality. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1995.tb00501.x

Press, Stata. (2019). Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. StataCorp LLC.

Stuckler, D., Basu, S., & McKee, M. (2010). Budget crises, health, and social welfare programmes. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c3311

The World Bank. (2014). GDP per capita (current US$). Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD

UNICEF. (2021). Child poverty. For Every Child. https://www.unicef.org/social-policy/child-poverty

Vansteenkiste, M., Ryan, R. M., & Soenens, B. (2020). Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. In Motivation and Emotion. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-019-09818-1

Wilkinson, R. G., & Pickett, K. E. (2006). Income inequality and population health: A review and explanation of the evidence. Social Science and Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.036

Zaborskis, A., & Grincaite, M. (2018). Gender and age differences in social inequality on adolescent life satisfaction: A comparative analysis of health behaviour data from 41 countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15071297

Zaborskis, A., Grincaite, M., Lenzi, M., Tesler, R., Moreno-Maldonado, C., & Mazur, J. (2019). Social Inequality in Adolescent Life Satisfaction: Comparison of Measure Approaches and Correlation with Macro-level Indices in 41 Countries. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1860-0

Funding

HBSC is an international study carried out in collaboration with the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. The International Coordinator of the 2013/14 survey was Candace Currie (then at the University of St Andrews). The Data Bank Manager was Professor Oddrun Samdal (University of Bergen). The study included data from the following 30 countries (Principal Investigators at the time in brackets): Austria (Rosemarie Felder-Puig), Flemish Belgium (Carine Vereecken, Anne Hublet), French Belgium (Danielle Piette), Bulgaria (Lidiya Vasileva), Croatia (Marina Kuzman, Ivana Pavic Simetin), Czech Republic (Michal Kalman), Denmark (Pernille Due, Mette Rasmussen), England (Antony Morgan, Fiona Brooks), Estonia (Katrin Aasvee), Finland (JormaTynjälä), France (Emmanuelle Godeau), Germany (Matthias Richter, Petra Kolip), Greece (Anna Kokkevi), Hungary (ÁgnesNémeth), Ireland (Saoirse NicGabhainn, Michal Molcho), Italy (Franco Cavallo), Latvia (Iveta Pudule), Lithuania (Apolinaras Zaborskis), Luxembourg (Yolande Wagener), Malta (Charmaine Gauci), Netherlands (Gonneke Stevens, Saskia van Dorsselaer), Poland (Joanna Mazur), Portugal (Margarida Gaspar de Matos), Romania (Adriana Baban), Scotland (Candace Currie, Jo Inchley), Slovakia (Andrea Madarasová Gecková), Slovenia (Helena Jericek), Spain (Carmen Moreno Rodriguez), Sweden (Lilly Augustine, Petra Lofstedt), and Wales (Chris Roberts). For details, see http://www.hbsc.org.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Not Applicable.

Consent to participate

Either active-consent or passive-consent approaches depending on country and school board requirements were used.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hammami, N., Erdoğan, Y. & Elgar, F.J. Socioeconomic Position Mediates the Relationship between Family Social Benefits and Adolescent Life Satisfaction in 25 countries. Child Ind Res 15, 1761–1775 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-022-09929-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-022-09929-1