Abstract

Sense of school belonging has a strong impact on adolescents’ well-being, and whilst there are many factors that can influence school belonging, two of the most salient factors include perceived teacher support and exposure to bullying . While the association between school belonging and teacher support and school belonging and exposure to bullying are well documented in the literature, less is known about how these relationships vary depending on students’ socioeconomic status (SES). The aim of this study was to investigate whether SES moderated the relationship between school belonging and these school-related factors. The sample was drawn from the 14,273 Australian 15 and 16-year-olds who completed the 2018 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) survey. Linear regression analyses revealed that the association between school belonging and teacher support was not moderated by SES and there was a positive relationship between SES and sense of school belonging, even after accounting for teacher support, exposure to bullying and other student and school characteristics. Despite limitations, this study fills a gap in the literature, provides a foundation for further research to build on, and has potential implications for how safety should be promoted for students of both high and low SES for teacher support to more strongly influence their sense of school belonging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Students’ sense of school belonging, which is the extent to which students “feel personally accepted, respected, included, and supported by others – especially teachers and other adults in the school social environment” (Goodenow & Grady, 1993, p. 60-61), is well established in the literature to be strongly influenced by teacher support and exposure to bullying (Arslan & Allen, 2021; Allen et al., 2018; Cunningham, 2007; Garcia-Reid, 2007; Holt & Espelage, 2003; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD], 2019; Wang & Holcombe, 2010). However, there is mixed and limited research regarding whether students’ socioeconomic status (SES) moderates the relationship between school belonging and these school-related factors (Berkowitz et al., 2016; Cemalcilar, 2010; Croninger & Lee, 2001; Yue, 2017). This study aims to extend on previous research (Berkowitz et al., 2016; Cemalcilar, 2010; Croninger & Lee, 2001; Yue, 2017) and fill the relevant gaps in the literature by exploring whether SES can moderate the relationship between school belonging and teacher support and school belonging and exposure to bullying.

1 School Belonging, Perceived Teacher Support, and Exposure to Bullying

Whilst feeling like one belongs is important for all age groups, it may be especially relevant for adolescents (Arslan et al., 2022; Allen & Bowles, 2012; Allen, 2020). Students who report a high sense of school belonging display higher academic motivation and achievement (Allen et al., 2018; Goodenow & Grady, 1993; OECD, 2013; Wang & Holcombe, 2010), increased prosocial behaviour (Arslan & Tanhan, 2019; Catalano et al., 2004), a reduced probability of dropping out of school (McWhirter et al., 2018), higher life satisfaction (Arslan et al., 2021; OECD, 2017a), higher levels of self-esteem (Nutbrown & Clough, 2009), and lower levels of depression (Arslan, 2021; Parr et al., 2020). Having a sense of school belonging at this age is associated with the formation of a positive identity (Brechwald & Prinstein, 2011), assists with successful psychosocial adjustment (Lonczak et al., 2002), and aids the transition from childhood into adulthood (Parker et al., in press; Tanti et al., 2011). Despite the benefits linked with a greater sense of school belonging, Australian students have recently tended to report a weaker sense of belonging at school compared to students from other countries (De Bortoli, 2018). In addition, Australian adolescent students’ sense of school belonging has been significantly declining since 2003 (De Bortoli, 2018), indicating the importance of researching this population group.

Students who perceive their teachers as highly supportive tend to feel a stronger sense of belonging at school compared to students who do not view their teachers as supportive (Allen et al., 2021; Garcia-Reid, 2007; Wang & Holcombe, 2010). Perceived teacher support can be defined as the extent to which students feel like their teachers care about them and their achievements, encourage them, take the time to assist them, treat them fairly, promote mutual respect, and provide opportunities for independent decision-making (Allen et al., 2018; OECD, 2019b; Wang & Holcombe, 2010). Supportive teachers provide both personal and academic help, praise good behaviour and work, and their students feel a connection to them (Allen et al., 2018). While teacher support has been found to have one of the strongest effect sizes for school belonging (Allen et al., 2018), exposure to bullying, including feelings of safety, has also been found to have an important influence on school belonging (Craggs & Kelly, 2018; Cunningham, 2007; Holt & Espelage, 2003).

Students who are frequently bullied tend to report a weaker sense of school belonging compared to students who are not frequently bullied (Cunningham, 2007; Holt & Espelage, 2003; OECD, 2019b). Bullying is an aggressive, unwanted, and negative behaviour that includes someone intentionally and repeatedly harming and/or discomforting another person who is weaker and has difficulty defending themselves (Arslan et al., 2020; Nesdale & Scarlett, 2004; OECD, 2019b; Olweus, 1995). Bullying can be physical (e.g., hitting, kicking, pinching, pushing), verbal (e.g., name calling, teasing, threatening), or relational (e.g., social exclusion, spreading gossip, humiliation) (Wolke et al., 2000; Woods & Wolke, 2004). Those who are victims of bullying tend to report feeling unsafe at school (Berkowitz & Benbenishty, 2012; Glew et al., 2005). Research suggests that social support, especially from peers, may help to buffer some of the negative consequences victims of bullying tend to experience, particularly anxiety, depression, and low quality of life (Flaspohler et al., 2009; Holt & Espelage, 2007). Sense of school belonging, perceived teacher support, and exposure to bullying are all associated with students’ SES (De Bortoli, 2018; OECD, 2019b).

2 Theoretical Framework: Socioeconomic Status

Sense of school belonging, perceived teacher support, and exposure to bullying are all affected by students’ SES (De Bortoli, 2018; OECD, 2019b). A low SES is associated with a lower income, level of wealth, and educational achievement, whereas a high SES is related to a higher income, level of wealth, and educational achievement (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002). An individual’s occupational status can also provide information about their level of education and income, as well as other job-related skills and benefits (Burgard et al., 2003).

Australian students who come from high SES families tend to report a greater sense of school belonging, generally perceive their teachers as more supportive, and tend to be less exposed to bullying compared to students from low SES families (Cemalcilar, 2010; De Bortoli, 2018; OECD, 2019b). While the association between school belonging and teacher support and school belonging and exposure to bullying are both strong and prevalent across the literature (Allen et al., 2018; Cunningham, 2007; Garcia-Reid, 2007; Holt & Espelage, 2003; OECD, 2019b; Wang & Holcombe, 2010), less is known about how students’ SES may influence these relationships. This study aims to fill this gap in the literature, with Maslow’s (1943) theory of human motivation offering insight into how SES may impact the relationship between school belonging and these school-related factors in Australian adolescents.

Maslow’s (1943) theory of human motivation may provide a theoretical framework for the observed differences in students’ sense of school belonging by SES. Maslow (1943) argued that each need, starting with the lowest-level need, must first be satisfied before the need above it can emerge, and it is the desire to fulfil higher-level needs that serves as a motivator for individuals to achieve and improve. It is reasonable to assume that a student’s most basic and essential requirements for survival, which may include food, sleep, and shelter (Maslow, 1943; Nuñez, 2016), are threatened in the presence of low SES. Therefore, the need for belongingness—which encompasses a desire for interpersonal connections and acceptance from others which are reciprocal and gained through genuine relationships such as those with family, friends, and teachers—at school may be more difficult to satisfy if the student’s most basic needs are ungratified (Maslow, 1943; Nuñez, 2016; Slaten et al., 2016).

Individuals from low SES backgrounds may not be able to afford adequate amounts of food, and the food they do consume tends to be less healthy compared to what individuals from high SES backgrounds eat (Cunningham, 2018; Konttinen et al., 2013). More common issues for this population group are the barriers they face in meeting their safety needs. In Australia, individuals of a lower SES tend to experience higher crime and domestic abuse rates compared to those of a higher SES (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2013; Kerr, 2018). Furthermore, people living in neighbourhoods with unsatisfactory social and physical conditions (high occurrences of public disturbance, drug-dealing, uncivil behaviours, diminished quality and maintenance of property, and litter and graffiti) tend to experience a greater fear of crime compared to those living in neighbourhoods with satisfactory social and physical conditions (Perkins & Taylor, 1996). These characteristics are more common in low SES neighbourhoods, and those who experience them tend to have a greater fear of crime and concerns for the safety of themselves and household members (Perkins & Taylor, 1996).

In further support of this notion, findings from Meyer et al. (2014) indicate that low SES is associated with greater neighbourhood safety concerns, and according to Garcia-Reid (2007), students who perceive their neighbourhoods as less safe tend to have a lower sense of belonging at school. In addition, violence and behavioural problems, including fighting, threats, and sexual offenses, are more prevalent in low SES schools (Boroughs et al., 2006). Such behavioural problems are associated with a negative school climate in which students are unable to get along well with each other and staff, and this type of environment is correlated with lower perceived school safety (DeRosier & Newcity, 2005).

Overall, it appears that individuals from low SES backgrounds tend to face more barriers in meeting their safety needs compared to students from high SES backgrounds. According to Maslow (1943), this indicates that students of a low SES will generally have a weaker sense of school belonging compared to individuals of a high SES, which has been found in the literature (De Bortoli, 2018; OECD, 2019b). This has implications for how the relationship between school belonging and perceived teacher support may vary based on students’ SES. While Maslow’s theory notes that a need does not need to be fully satisfied for the next need to emerge (Maslow, 1943), it is possible that SES may have a role in moderating how school belonging is fulfilled.

3 Socioeconomic Status on the Relationship Between Teacher Support and School Belonging

Although perceived teacher support tends to be positively associated with sense of school belonging (Allen et al., 2018; Garcia-Reid, 2007; Wang & Holcombe, 2010), Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs may be used to infer the relationship between teacher support and school belonging will be weaker for students of a low SES compared to students of a high SES, due to the barriers students of a low SES tend to face in meeting their safety needs.

Two key studies provide a basis of support for this notion. Cemalcilar (2010) investigated the influence of school social relationships on students’ sense of school belonging across low and high SES schools, and their findings inferred that high-quality teacher-student relationships were not as strong in fostering a sense of school belonging for students attending low SES schools compared to students attending high SES schools. This study examined students’ attitudes towards teacher-student relationships regarding the general atmosphere in the school, rather than their personal perceptions and interactions. Similarly, Yue (2017) explored whether the association between school SES and youth depressive symptoms differed according to the amount of perceived teacher support students received. Results indicated that teacher support was not as strong in reducing students’ depressive symptoms for low SES schools compared to high SES schools.

Cemalcilar (2010) and Yue (2017) examined concepts related to teacher support (satisfaction with teacher-student relationships) and school belonging (depression) but not those factors specifically. This highlights the need for the current study to examine whether Cemalcilar’s (2010) and Yue’s (2017) results extend to perceived teacher support and sense of school belonging, which, if so, would result in the association between perceived teacher support and sense of school belonging being stronger for students of a high SES compared to students of a low SES. However, there is also literature that suggests teacher support can buffer the negative experiences students of a low SES tend to face (Berkowitz et al., 2016; Croninger & Lee, 2001).

4 Teacher Support as a Compensating Factor

Research suggests that teacher support can help compensate for the challenges students from lower SES backgrounds face in achieving a strong sense of school belonging by providing a sense of safety at school (Berkowitz et al., 2016; Brody et al., 2002; Croninger & Lee, 2001). Lenzi et al. (2017) discovered that higher perceived teacher support at the individual level was associated with students feeling safer at school; however, this was determined for students in general rather than specifically for students of a lower SES. If teacher support can provide a sense of security for students who face unique challenges in meeting their safety needs, then Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs would indicate that teacher support should positively influence sense of school belonging equally for students of a low or high SES.

Two key studies (Berkowitz et al., 2016; Croninger & Lee, 2001) provide insight into how teacher support may serve as a protective factor for students of a low SES. Berkowitz et al. (2016) explored whether a positive school climate, which can be defined as the ‘personality’ of the school and includes teacher support, would lessen the negative effect a low SES had on students’ academic achievement. Their findings revealed that a positive school climate was effective in contributing to higher academic achievement for students from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds, thus decreasing the negative influence low SES has on academic achievement (Berkowitz et al., 2016). Similarly, Croninger and Lee (2001) examined the effects of teacher support on the likelihood of students dropping out of school. They discovered that teacher support reduced the likelihood of students dropping out of school by nearly half. Although these findings were relevant to generally all students, those from socially disadvantaged backgrounds benefited the most.

Although academic achievement and school belonging are positively correlated (Allen et al., 2018; OECD, 2019b), and the likelihood of dropping out of school is inversely linked to school belonging (McWhirter et al., 2018), further research is needed to examine whether the results from the studies by Berkowitz et al. (2016) and Croninger and Lee (2001) extend to school belonging specifically, which is what the current study aims to investigate. The findings from the studies by Berkowitz et al. (2016) and Croninger and Lee (2001) suggest that students of a low SES who receive high levels of teacher support will also report high levels of school belonging despite the challenges they face. Exposure to bullying is another factor which may have varying associations with students’ sense of school belonging, depending on their SES.

5 Socioeconomic Status and the Relationship Between Bullying and School Belonging

The negative relationship between exposure to bullying and sense of school belonging may also vary depending on students’ SES (Cemalcilar, 2010). Victims of bullying, including victims who are also bullies, generally report feeling less safe at school and tend to report a weaker sense of school belonging compared to students who are bullies or not involved in bullying (Berkowitz & Benbenishty, 2012; Glew et al., 2005). This research is congruent with Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs, as when one’s safety needs are compromised their sense of belonging is likely to be weaker than those who can fulfil their safety needs. However, these studies did not examine potential differences related to SES, and there is research, although limited, that indicates the influence of bullying on school belonging may vary depending on students’ SES.

Cemalcilar (2010) investigated whether the relationship between students’ perceived violence in the school and their sense of school belonging differed based on the schools’ SES. The findings uncovered that perceived violence in the school had a negative relationship with sense of school belonging only for high SES schools, indicating that violence in schools was not a factor that significantly influenced students’ sense of school belonging in low SES schools. Cemalcilar (2010) did not predict this finding but suggested it may be due to students from low socioeconomic backgrounds being more accustomed to unsafe environments, and thus their sense of safety and school belonging is less affected by violence in the school. However, for students from high socioeconomic backgrounds, it is thought that because they are not adjusted to unsafe environments, the presence of any violent acts may affect their sense of safety and school belonging more strongly (Cemalcilar, 2010). Cemalcilar (2010) investigated students’ general perceptions of violence in schools, rather than their direct experience of bullying. The current study is needed to determine whether the negative relationship between exposure to bullying and school belonging is also only significant for students of a high SES, or rather whether direct exposure to bullying imposes a bigger threat to the safety of students of a low SES compared to general perceptions of violence.

Overall, due to the threat bullying imposes on one’s sense of safety, it is possible that students who are frequently bullied will report a weaker sense of school belonging equally across low and high SES. However, it is also suggested that exposure to bullying may affect students’ sense of school belonging more strongly for students of a high SES, due to students of a low SES being more accustomed to unsafe environments (Cemalcilar, 2010).

6 The Current Study

Research regarding how the relationship between teacher support and school belonging may differ according to students’ SES is mixed, with some literature indicating that students of a low SES do not experience the benefits of teacher support (Cemalcilar, 2010; Yue, 2017) and other research suggesting that teacher support can mitigate the challenges students of a low SES face (Berkowitz et al., 2016; Croninger & Lee, 2001). There is also no current research that specifically explores whether the association between perceived teacher support and sense of school belonging differs based on students’ SES. Furthermore, the literature concerning how SES may impact the relationship between exposure to bullying and sense of school belonging is extremely limited, with one key study providing a foundation for further research (Cemalcilar, 2010). Therefore, the current study intends to fill a gap in the literature as well as extend on past research (Berkowitz et al., 2016; Cemalcilar, 2010; Croninger & Lee, 2001; Yue, 2017). This research aims to investigate whether SES is a moderating variable, meaning it affects the strength of associations, for the relationship between sense of school belonging and perceived teacher support and sense of school belonging and exposure to bullying. The current study has important implications regarding where and when teacher support and bullying interventions should be promoted or, rather, if other factors, such as safety, should be targeted first.

Due to the mixed and limited literature, two research questions are proposed:

RQ1. Does students’ socioeconomic status moderate the relationship between perceived teacher support and students’ sense of school belonging?

RQ2. Does students’ socioeconomic status moderate the relationship between exposure to bullying and students’ sense of school belonging?

7 Method

7.1 Participants

This study uses data from the 2018 Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) (OECD, 2019b). A total of 14,273 Australian students across the 740 educational institutions participated in this iteration of the program. PISA targets 15-year-old students attending schools in grade 7 or higher across school sectors (OECD, 2019a ,2019b).

Students were given two hours to complete a cognitive assessment and completed a student questionnaire about certain aspects of their home, family, and school background, as well as their learning experiences and attitudes towards school, which took around 30 minutes to complete. Data was gathered between late July and early September 2018 (OECD, 2017b; Thompson et al., 2019).

The OECD uses a two-stage stratified sample design (OECD, 2019a). First, a stratified sample of school is selected based on size, state, sector (Catholic, government, or independent) and level (vocational—TAFE, in Australia—or secondary education). Then, students are selected within these schools. If the school has less than 42 students, all students are included, otherwise, a sample of 42 students within the school is randomly selected. This complex sample design implies that not all PISA participants have the same probability of being selected to participate in the study. To adjust for this, the OECD recommends using sampling weights that they calculate to make the sample representative of 15-year-old students attending schools in grade 7 or higher (OECD, 2019b). As this study focuses on Australian students, sample weights have been normalised for the observations in the dataset (OECD, 2009).

7.2 Measures

Measures for this study were drawn from the PISA 2018 computer-based Student Questionnaire (OECD, 2017c). The OECD creates a series of indices combining relevant items in a series of scaled indices using item-response-theory scaling methodology (OECD, 2019a). The resulting indices have a world-wide mean of zero and a standard deviation of 1. The indices were re-standardised to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of 1 for the subsample of Australian participants so that the resulting estimates can be interpreted as effect sizes. The following describes the items that the OECD used in the construction of each index.

Index of Sense of Belonging

Sense of school belonging was measured using a set of six items. Participants were asked to answer the extent to which they agreed with six statements, e.g., “I feel like an outsider (or left out of things) at school”. Participants responded using a four-point Likert-type item ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree). Some items were reversed scored, which allowed for higher scores to indicate higher levels of sense of school belonging. The internal consistency of the six items measuring sense of school belonging was satisfactory with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84.

Index of Teacher Support

Perceived teacher support was assessed using a set of four items. Participants were asked to indicate how often certain things happened in their English lessons, e.g., “The teacher shows an interest in every student’s learning”. Participants responded using a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (every lesson) to 4 (never or hardly ever). Responses had to be reverse coded so that higher scores indicate higher levels of perceived teacher support. The internal consistency of the four items measuring perceived teacher support was 0.91.

Index of Exposure to Bullying

Exposure to bullying was depicted using a set of six items. Participants were asked how often during the past 12 months they had had certain experiences in school or social media, e.g., “Other students made fun of me”. Participants responded via a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never or almost never) to 4 (once a week or more), with higher scores indicating higher exposure to bullying. The internal consistency of the six items measuring exposure to bullying was 0.80.

Socioeconomic Status: SES was measured using the index of economic, social and cultural status (ESCS). ESCS is based on the indicators of parental education, highest parental occupation, and home possessions including total number of books in the home. The internal consistency of the ESCS scale was 0.60 (OECD, 2017b). This indicator was then split into three groups: low SES, for the first quartile of ESCS; middle SES, for the second and third quartiles of ESCS; and high SES, for the fourth quartile of ESCS.

Additional Control Variables

In addition to the main variables described above, additional variables were included in the analysis as they may influence the relationship between the students’ sense of school belonging, socioeconomic status, teacher support and exposure to bullying. These control variables included the student’s gender, age and international grade, and the schools’ ownership (private government-dependent, private independent and public), student-teacher ratio and the proportion of fully certified teachers.

7.3 Statistical Analyses

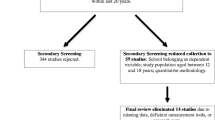

Linear regression analyses were conducted to investigate whether SES moderated the relationship between perceived teacher support and sense of school belonging and exposure to bullying and sense of school belonging. Model 1 explores the relationship between sense of school belonging and perceived teacher support, exposure to bullying and SES, conditional on student characteristics. Model 2 tests if SES moderates the relationships between sense of school belonging and perceived teacher support and sense of school belonging and exposure to bullying by adding two interaction terms between SES and perceived teacher support/exposure to bullying. Model 3 tests if these findings persist after adding school characteristics. Finally, Model 4 adds school fixed effects to test if, within schools, students with low SES are more or less affected by teacher support and exposure to bullying. All the models incorporate sampling weights to account for PISA’s complex sample design. These models are estimating by maximizing the Horvitz-Thompson estimator of the population likelihood using the survey package for R version 3.6.2 (Lumley, 2004; R Core Team, 2019).

Missing values were excluded listwise from the data, as they were found not to be missing at random, as suggested by Schafer and Graham (2002). After excluding missing values, the final sample consists of 7,723 students across 528 schools.

8 Results

8.1 Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents the means and 95% confidence intervals for sense of school belonging, perceived teacher support, and exposure to bullying by SES.

As can be seen from Table 1, results indicate that the average score for sense of school belonging and perceived teacher support was higher for students of a high SES compared to students of a low SES, whereas the average score for exposure to bullying was higher for students of a low SES compared to students of a high SES.

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for the variables to be included in the analyses. Belonging, Teacher support and Bullying are not included because they have a mean of zero and standard deviation of one, as they have been standardised.

8.2 Linear Regression Analyses

Linear regression analyses were performed to identify if SES moderated the relationship between sense of school belonging and perceived teacher support and sense of school belonging and exposure to bullying. The estimation results are reported in Table 3.

Sense of School Belonging and Perceived Teacher Support

Model 1 shows that teacher support was found to be statistically significant in predicting sense of school belonging [B = 0.089, p < 0.001], even after accounting for exposure to bullying, SES and other student characteristics. However, there is no evidence to support the hypothesis that SES moderates this relationship [Working Deviance = 1.788, p = 0.409]. Model 3 shows that these results prevail even after accounting for school characteristics. Finally, Model 4 shows that, within schools, students who perceive higher levels of teacher support also report higher levels of sense of school belonging [B = 0.054, p = 0.03], after accounting for other student characteristics.

Sense of School Belonging and Exposure to Bullying

Exposure to bullying was found to be statistically significant in predicting sense of school belonging [B = − 0.357, p < 0.001], even after accounting for perceived teacher support, SES and other student characteristics. However, there is no evidence of a moderation effect from SES [Working Deviance = 0.871, p = 0.647]. Model 3 shows that these results did not change after considering school characteristics. Model 4 shows that, within schools, students who have been exposed to bullying tend to report lower levels of sense of school belonging belonging [B = − 0.328, p < 0.001], even after accounting for other student characteristics.

9 Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether SES would serve as a moderator for the relationship between sense of school belonging and perceived teacher support and sense of school belonging and exposure to bullying. Results revealed that SES did not moderate the relationship between school belonging and teacher support, nor the relationship between school belonging and exposure to bullying.

9.1 Socioeconomic Status as a Moderator

The finding that the association between school belonging and teacher support was not moderated by SES contrasts with past research by Cemalcilar (2010) and Yue (2017). However, the finding that there is a positive relationship between SES and sense of school belonging, even after accounting for teacher support and exposure to bullying and other student and school characteristics, supports Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs, in the sense that when one cannot adequately meet their safety needs, their love and belongingness needs will not be as highly fulfilled. As previously discussed, it was suggested that because students of a low SES tend to face more barriers in meeting their safety needs compared to students of a high SES (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2013; Boroughs et al., 2006; DeRosier & Newcity, 2005; Garcia-Reid, 2007; Kerr 2018; Meyer et al., 2014; Perkins & Taylor, 1996), overall, it appears that teacher support can increase all students’ sense of school belonging for all students.

Past research has identified teacher support to be one of the strongest predictors for sense of school belonging (Allen et al., 2018; Garcia-Reid, 2007; Wang & Holcombe, 2010), which is consistent with the findings in this study. Previous definitions of teacher support describe it as including both personal and academic help (Allen et al., 2018). However, in the present study, the questions that the OECD (2017c) included as a measure of perceived teacher support primarily focused on perceived academic support, which may imply that academic support is also important, beyond personal support, although past research (Kiefer et al., 2015) indicates that emotional support from teachers is superior in promoting students’ sense of school belonging compared to academic support. Kiefer et al. (2015) also noted that academic support was most effective within the context of emotional support. The exclusion of examining emotional support from teachers in this study may account for the lack of differences in the strength of the relationship between perceived teacher support and sense of school belonging for students of a low and high SES.

Another consideration as to why these findings arose may be because perceived teacher support was only measured in relation to English teachers. The focus of the 2018 PISA cycle was reading literacy; therefore, support from English teachers was examined in isolation to allow for connections between English teacher support and reading literacy to be established. The results from the current study should be interpreted with caution as they can only be generalised to academic support received from English teachers.

9.2 Exposure to Bullying and Safety

Limited past research has examined sense of school belonging and exposure to bullying by SES (Cemalcilar, 2010). The one key study that was discussed found that perceived school violence was not a factor that significantly affected school belonging for low SES schools (Cemalcilar, 2010). In contrast, the current study found that students’ school belonging was equally negatively affected by exposure to bullying for students of a low and high SES. Cemalcilar (2010) argued that their results may be due to students of a low SES being more accustomed to unsafe environments and therefore their feelings of safety were less influenced compared to students of a high SES. However, Cemalcilar (2010) explored students’ general perceptions of violence in the school, whereas the current study measured students’ direct exposure to bullying.

It is suggested that direct exposure to bullying tends to negatively affect students’ feelings of safety and sense of school belonging more so than general perceptions of violence in the school (Glew et al., 2008). Past research by Glew et al. (2008) discovered that victims of bullying were more likely to feel less safe at school and as though they do not belong compared to bystanders. It is indicated that even though students of a low SES may be more accustomed to unsafe environments, this only lessens the chance that they will feel unsafe when they are a bystander to violence but not when they are a victim themselves, as bystanders do not directly experience harm (Glew et al., 2008).

Glew et al.’s (2008) findings also allow for the present study’s results to be explained in the context of Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs. Due to bullying strongly compromising victims’ feelings of safety (Glew et al., 2008), it is logical that frequently bullied students of a low and high SES were equally negatively affected in their sense of school belonging compared to students who were not frequently bullied. Based on these findings, it is suggested that bullying interventions are implemented equally in low and high SES schools.

Taken together, the present study provides further evidence for the importance of creating a safe school environment for students (Allen et al., 2016). A school climate that has low to absent bullying and a strong culture of teacher support is best to support student belonging (Arslan & Allen, 2021).

9.3 Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Limitations should be considered when interpreting this study’s findings. As previously discussed, the measure of perceived teacher support primarily focused on academic support rather than emotional support from teachers and only examined teacher support in the context of English teachers. To allow for greater generalisability and likely result in perceived teacher support explaining more of the variance in school belonging, it is recommended that future studies examine teacher support in the context of both emotional and academic support and examine how teacher support received across all subjects affects students’ school belonging. The results can also only be generalised to countries that have similar ESCS conditions to Australia. Therefore, it is suggested that future research be carried out in other countries to examine how the results may vary across different ESCS conditions.

10 Conclusions

In conclusion, perceived teacher support and exposure to bullying had an effect on sense of school belonging for students of both a low and high SES. This paper contrasts with previous research (Cemalcilar, 2010; Yue, 2017) that indicates teacher support tends to be more effective in promoting school belonging for students of a high SES compared to students of a low SES. It also contradicts the limited past research that suggests violence in schools tends to negatively influence school belonging more greatly for students of a high SES (Cemalcilar, 2010); however, this was determined to be because the current study examined exposure to bullying rather than perceptions of violence in the school. Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs was used as a theoretical framework for this study and has assisted in explaining the results through the lens of feelings of safety.

The current study was of an explorative nature, and it is recommended that future research investigating the relationships between school belonging and these school-related factors in relation to SES be conducted. Overall, this study fills a gap in the literature and provides a foundation for future research to build on, with the aim being to discover how Australian adolescents’ sense of school belonging is uniquely affected, in order to assist in the development of interventions to improve it.

Availability of Data and Material

The present study used secondary data from the 2018 OECD PISA survey, and the dataset used is publicly available from the OECD website.

Code Availability

The analysis uses R version 3.6.2. The script file can be accessed via. https://doi.org/10.26180/18400262.

References

Allen, K., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., & Waters, L. (2018). What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-016-9389-8

Arslan, G., & Allen, K. A. (2021). School victimization, school belongingness, psychological well-being, and emotional problems in adolescents. Child Indicators Research, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-021-09813-4

Allen, K. A., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Waters, L. (2016). Fostering school belonging in secondary schools using a socio-ecological framework. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 33(1), 97–121. https://doi.org/10.1017/edp.2016.5

Allen, K. A., & Bowles, T. (2012). Belonging as a guiding principle in the education of adolescents. Australian Journal of Educational and Developmental Psychology, 12, 108–119

Allen, K. A. (2020). The Psychology of belonging. Routledge (Taylor and Francis Group)

Allen, K. A., Slaten, C., Arslan, G., Roffey, S., Craig, H., & Vella-Brodrick, D. (2021). School belonging: The importance of student-teacher relationships. In P. Kern, & M. Streger (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of positive education. Palgrave & Macmillan. https://www.palgrave.com/gp/book/9783030645366

Arslan, G., Allen, K. A., & Tanhan, A. (2020). School bullying, mental health, and wellbeing in adolescents: Mediating impact of positive psychological orientations. Child Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-020-09780-2

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2013). Crime in Australia. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/1370.0~2010~Chapter~Crime%20in%20Australia%20(4.4.5)

Berkowitz, R., & Benbenishty, R. (2012). Perceptions of teachers’ support, safety, and absence from school because of fear among victims, bullies, and bully-victims. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(1), 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01132.x

Berkowitz, R., Moore, H., Astor, R. A., & Benbenishty, R. (2016). A research synthesis of the associations between socioeconomic background, inequality, school climate, and academic achievement. Review of Educational Research, 87(2), 425–469. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316669821

Boroughs, M., Massey, O. T., & Armstrong, K. H. (2006). Socioeconomic status and behavior problems: Addressing the context for school safety. Journal of School Violence, 4(4), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1300/J202v04n04_03

Bradley, R. H., & Corwyn, R. F. (2002). Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 371–399

Brechwald, W. A., & Prinstein, M. J. (2011). Beyond homophily: A decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 166–179

Brody, G. H., Dorsey, S., Forehand, R., & Armistead, L. (2002). Unique and protective contributions of parenting and classroom processes to the adjustment of African American children living in single-parent families. Child Development, 73(1), 274–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00405

Burgard, S., Stewart, J., & Schwartz, J. (2003). Occupational Status. MacArthur, Research Network on SES & Health

Catalano, R. F., Haggerty, K. P., Oesterle, S., Fleming, C. B., & Hawkins, J. D. (2004). The importance of bonding to school for healthy development: Findings from the Social Development Research Group. Journal of School Health, 74(7), 252–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08281.x

Cemalcilar, Z. (2010). Schools as socialisation contexts: Understanding the impact of school climate factors on students’ sense of school belonging. Applied Psychology, 59(2), 243–272. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2009.00389.x

Craggs, H., & Kelly, C. (2018). Adolescents’ experiences of school belonging: a qualitative meta-synthesis. Journal of Youth Studies, 21(10), 1411–1425. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2018.1477125

Croninger, R. G., & Lee, V. E. (2001). Social capital and dropping out of high school: Benefits to at-risk students of teachers’ support and guidance. Teachers College Record, 103(4), 548–581. https://doi.org/10.1111/0161-4681.00127

Cunningham, N. J. (2007). Level of bonding to school and perception of the school environment by bullies, victims, and bully victims. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 27(4), 457–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431607302940

Cunningham, P. (2018). Why Even Healthy Low-Income People Have Greater Health Risks Than Higher-Income People. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2018/healthy-low-income-people-greater-health-risks

De Bortoli, L. (2018). PISA Australia in Focus Number 1: Sense of belonging at school. Australian Council for. https://research.acer.edu.au/ozpisa/30 Educational Research (ACER)

DeRosier, M. E., & Newcity, J. (2005). Students’ perceptions of the school climate: implications for school safety. Journal of School Violence, 4(3), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1300/J202v04n03_02

Flaspohler, P. D., Elfstrom, J. L., Vanderzee, K. L., Sink, H. E., & Birchmeier, Z. (2009). Stand by me: The effects of peer and teacher support in mitigating the impact of bullying on quality of life. Psychology in the Schools, 46(7), 636–649. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20404

Garcia-Reid, P. (2007). Examining social capital as a mechanism for improving school engagement among low income Hispanic girls. Youth & Society, 39(2), 164–181. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0044118 × 07303263

Glew, G. M., Fan, M. Y., Katon, W., Rivara, F. P., & Kernic, M. A. (2005). Bullying, psychosocial adjustment, and academic performance in elementary school. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 159(11), 1026–1031. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.159.11.1026

Glew, G. M., Fan, M. Y., Katon, W., & Rivara, F. P. (2008). Bullying and school safety. The Journal of Pediatrics, 152(1), 123–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.05.045

G?kmen, Arslan Jolanta, Burke Silvia, Majercakova Albertova Strength-based parenting and social-emotional wellbeing in Turkish young people: does school belonging matter?. Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/20590776.2021.2023494

G?kmen, Arslan Kelly-Ann, Allen (2021) School Victimization School Belongingness Psychological Well-Being and Emotional Problems in Adolescents. Child Indicators Research, 14(4) 1501–1517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-021-09813-4

G?kmen, Arslan Ahmet, Tanhan (2019) Ergenlerde Okul Aidiyeti Okul ??levleri ve Psikolojik Uyum Aras?ndaki ?li?kinin ?ncelenmesi. Ya?ad?k?a E?itim, 33(2) 318–332. https://doi.org/10.33308/26674874.2019332127

G?kmen, Arslan (2021) School belongingness well-being and mental health among adolescents: exploring the role of loneliness. Australian Journal of Psychology, 73(1) 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530.2021.1904499

G?kmen, Arslan (2021) Measuring emotional problems in Turkish adolescents: Development and initial validation of the Youth Internalizing Behavior Screener. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 9(2) 198–207 https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2019.1700860

G?kmen, Arslan Kelly-Ann, Allen Tracii, Ryan (2020) Exploring the Impacts of School Belonging on Youth Wellbeing and Mental Health among Turkish Adolescents. Child Indicators Research, 13(5) 1619–1635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-020-09721-z

Goodenow, C., & Grady, K. E. (1993). The relationship of school belonging and friends’ values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. The Journal of Experimental Education, 62(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.1993.9943831

Holt, M. K., & Espelage, D. L. (2003). A cluster analytic investigation of victimization among high school students: Are profiles differentially associated with psychological symptoms and school belonging? Journal of Applied School Psychology, 19(2), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1300/J008v19n02_06

Holt, M. K., & Espelage, D. L. (2007). Perceived social support among bullies, victims, and bully-victims. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36(8), 984–994. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9153-3

IEA. (n.d.). Tools. Working with IEA Data. https://www.iea.nl/data-tools/tools#section-308

Kerr, J. (2018). What the figures reveal about poverty and domestic violence.ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-09-19/domestic-violence-and-poverty-statistics/10108140

Kiefer, S. M., Alley, K. M., & Ellerbrock, C. R. (2015). Teacher and peer support for young adolescents’ motivation, engagement, and school belonging. Rmle Online, 38(8), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404476.2015.11641184

Konttinen, H., Sarlio-Lähteenkorva, S., Silventoinen, K., Männistö, S., & Haukkala, A. (2013). Socio-economic disparities in the consumption of vegetables, fruit and energy-dense foods: the role of motive priorities. Public Health Nutrition, 16(5), 873–882. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980012003540

Lenzi, M., Sharkey, J., Furlong, M. J., Mayworm, A., Hunnicutt, K., & Vieno, A. (2017). School sense of community, teacher support, and students’ school safety perceptions. American Journal of Community Psychology, 60(3-4), 527–537. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12174

Lonczak, H. S., Abbott, R. D., Hawkins, J. D., Kosterman, R., & Catalano, R. F. (2002). Effects of the Seattle Social Development Project on sexual behavior, pregnancy, birth, and sexually transmitted disease outcomes by age 21 years. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 156(5), 438–447

Lumley, T. (2004). Analysis of complex survey samples. Journal of Statistical Software, 9(1), 1–19

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

McWhirter, E. H., Garcia, E. A., & Bines, D. (2018). Discrimination and other education barriers, school connectedness, and thoughts of dropping out among Latina/o students. Journal of Career Development, 45(4), 330–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845317696807

Meyer, O. L., Castro-Schilo, L., & Aguilar-Gaxiola, S. (2014). Determinants of mental health and self-rated health: a model of socioeconomic status, neighborhood safety, and physical activity. American Journal of Public Health, 104(9), 1734–1741. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302003

Nesdale, D., & Scarlett, M. (2004). Effects of group and situational factors on pre-adolescent children’s attitudes to school bullying. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28(5), 428–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250444000144

Nuñez, I. (2016). Academic expectations and sense of belonging among Hispanic high school students

Nutbrown, C., & Clough, P. (2009). Citizenship and inclusion in the early years: understanding and responding to children’s perspectives on ‘belonging’. International Journal of Early Years Education, 17(3), 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760903424523

OECD (2009). PISA Data Analysis Manual: SPSS, Second Edition. PISA, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264056275-en

OECD. (2013). PISA 2012 Results: Ready to Learn (Volume III): Students’ Engagement, Drive and Self-Beliefs. PISA, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264201170-en

OECD. (2017a). PISA 2015 Results (Volume III): Students’ Well-Being. PISA, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264273856-en

OECD (2017b). PISA 2015 Technical Report. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/2015-technical-report/PISA2015_TechRep_Final.pdf

OECD (2017c). Student questionnaire for PISA 2018 [Main survey version]. http://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/2018database/

OECD (2018). PISA 2018 Technical Report. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/pisa2018technicalreport/

OECD. (2019). PISA 2018 Results (Volume III): What School Life Means for Students’ Lives. PISA, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/acd78851-en

Olweus, D. (1995). Bullying at School: What We Know and What We Can Do. Wiley-Blackwell

Parker, P., Allen, K. A., Parker, R., Dickel, T., Guo, J., Marsh, H. W., & Basarkod, G. (in press). Does school belonging predict NEET Status in emerging adults? Journal of Educational Psychology.

Parr, E. J., Shochet, I. M., Cockshaw, W. D., & Kelly, R. L. (2020). General Belonging is a Key Predictor of Adolescent Depressive Symptoms and Partially Mediates School Belonging. School Mental Health, 12(3), 626–637. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-020-09371-0

Perkins, D. D., & Taylor, R. B. (1996). Ecological assessments of community disorder: Their relationship to fear of crime and theoretical implications. American Journal of Community Psychology, 24(1), 63–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02511883

R Core Team. (2019). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

Schafer, J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7(2), 147. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147

Slaten, C. D., Ferguson, J. K., Allen, K. A., Brodrick, D. V., & Waters, L. (2016). School belonging: A review of the history, current trends, and future directions. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 33(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1017/edp.2016.6

Tanti, C., Stukas, A. A., Halloran, M. J., & Foddy, M. (2011). Social identity change: Shifts in social identity during adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 34(3), 555–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.05.012

Thompson, S., De Bortoli, L., Underwood, C., & Schmid, M. (2019). PISA 2018: Reporting Australia’s Results. Volume I Student Performance

Wang, M. T., & Holcombe, R. (2010). Adolescents’ perceptions of school environment, engagement, and academic achievement in middle school. American Educational Research Journal, 47(3), 633–662. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831209361209

Wolke, D., Woods, S., Bloomfield, L., & Karstadt, L. (2000). The association between direct and relational bullying and behaviour problems among primary school children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41(8), 989–1002

Woods, S., & Wolke, D. (2004). Direct and relational bullying among primary school children and academic achievement. Journal of School Psychology, 42(2), 135–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2003.12.002

Yue, Y. (2017). The Impact of Positive School Experiences and School SES on Depressive Symptoms in Chinese Children: A Multilevel Investigation. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies, 8(2), 37–58. https://doi.org/10.18357/ijcyfs82201717758

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study. Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics Approval

The current study was approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee on the grounds that it adequately met the requirements of the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research Project ID: 23045.

Consent to Participate

Consent forms were not necessary for participants in the current study as participation was considered to represent consent (OECD, 2017b).

Consent for Publication

The authors provide their consent for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Allen, KA., Cordoba, B.G., Parks, A. et al. Does Socioeconomic Status Moderate the Relationship Between School Belonging and School-Related factors in Australia?. Child Ind Res 15, 1741–1759 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-022-09927-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-022-09927-3