Abstract

In this article, the variety of interpretations of the concept of professional competence with reference to vocational teachers is reviewed and discussed. Previous vocational teacher research has been found to focus on which professional competencies vocational teacher possess or should demonstrate, with little focus placed on how competence is defined, leaving a gap related to how the professional competence concept is perceived and constructed. Through a conceptual analysis method (CAM), which follows the data collection process of a systematic literature review, the researcher identifies the concept attributes that are commonly shared as well as neighboring concepts associated with professional competence. Findings indicate that only few studies detail solid concept definitions. Furthermore, there is an agreement amongst the researchers on the main attributes of professional competence, including the situated and developmental character of professional competence as well as its relationship with action. In regard to concept use, there are distinct interrelationships between professional competence, professionalism, performance and qualification. Most definitions regard the individual as the reference point and little to no discussion takes place regarding professional competence at a collective level. Because complex concepts like the one under study can lead to confusion, it is suggested that their use should be accompanied by a discussion of their various meanings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Empirical vocational educational research is attracting increased attention (Barabasch, 2017) as the knowledge requirements in work life and labour market have raised the question of productivity for education systems. The focus has shifted to “outcomes” at all education levels but particularly in vocational and adult education (Barabasch, 2017). Having a long history of use as a concept, professional competence carries a variety of ethical and ideological meanings, making the confusion surrounding the concept in the scientific field inevitable (Mulder, 2014). Roth (1971) interpreted competence as a threefold concept, referring to self – competence, professional competence and social competence. Professional competence as “the ability to act and judge in a particular profession, and hold responsible” (Roth, 1971 as cited in Klieme et al., 2008) is in focus. The current study is a conceptual review of how professional competence is defined and used in literature with reference to vocational teachers.

Within learning environments, rapid changes have placed new demands on vocational teachers to continuously update their competence (Fejes & Köpsen, 2014). This global trend combined with the multiple roles played by vocational teachers, such as tutors, mentors and practitioners (Mahlamäki-Kultanen et al., 2006), raises questions about which competence they should develop and how. Furthermore, international bodies (European Commission, 2010; OECD, 2010) promote initiatives on vocational teacher competence research and academia often follows their lead. However, vocational teacher research focuses heavily on which professional competence vocational teacher possess or should demonstrate, with only little focus placed on what competence represents (Andersson, Hellgren & Köpsén, 2018; Duch & Andreasen, 2015), thus, leaving a gap related to how professional competence as a concept is perceived and used empirically.

With vocational education varying across different countries, the profession of vocational teacher differs from one setting to another. This range of approaches in understanding and defining the profession creates a plurality of empirical manifestations of professional competence definitions. The lack of a unanimous definition leads to the existence of ambiguities which are not fruitful for constructive dialogue and theory development (Suddaby, 2010). Without communicating a clear understanding of the concept, discussion might be misleading and confusing (Tähtinen & Havila, 2018).

Professional competence, used widely in everyday communication and in the scientific field is, as any concept, a tool to understand the world. The nature of concepts´ use often requires them to be complex and abstract (Engeström et al., 2006). Yet, this nature allows them to assist individuals to grasp the world. Hence, the understanding of professional competence for vocational teachers is the basis for further study and development of their professionalism, as well for theory building.

The aim of this research study is to provide an overview of the concept of professional competence as used in vocational teacher research. The overview is guided by the questions of how the professional competence definition is used in the articles reviewed, how the concept is understood and defined by researchers and, finally, in what way the professional competence concept is used in empirical studies. The concept of competence is addressed first based on a historical review, while later the researcher explores how professional competence is captured and used in the vocational teacher research field. Through a conceptual analysis method (CAM), the researcher elucidates the confusion around the concept to highlight the complexity that the conceptual language use reflects. Thereafter, the review findings are presented. Finally, the discussion section focuses on the concept of professional competence based on the findings.

Competence over Time: Discussed as Motivation, Intelligence, Performance and Education

The concept of competence has a multidisciplinary background, which becomes obvious today as many disciplines are interested in its definition and use. The introduction of competence in psychology is credited to White (1959). White perceived competence as an effective interaction between the individual and their environment. Moreover, he stressed the motivational character of the concept stating that “there is a competence motivation as well as competence in its more familiar sense of achieved capacity.” (op cit, p. 318). For White (1959, p. 329) the motivation to become competent was named effectance and the feeling of achievement efficacy. The idea later was built upon in Bandura (1977).

An important contribution to the discussion is that of McClelland (1973), who demonstrated the disconnect between education and work, approaching competence as intelligence. He developed tests to predict competence, approaching the latter as the characteristic trait that underlies superior performance. Although McClelland’s ideas were heavily contested, measuring competence as a predictor of job performance, gradually replaced tests of cognitive intelligence (Pottinger & Goldsmith, 1979). Hence, assessing performance in practice was applied in the search for traits contributing to successful performance; these traits were described as competencies (Winterton et al., 2006). Psychology, interested in a concept that focuses on individual ability to cope with challenges in specific situations has, hence, contributed with a functional concept of competence.

Another influential development has been the movement towards performance improvement, starting in the 1960s. Dedicated to productivity improvement, it implied that looking solely at individual behaviour was not enough; workplaces, group dynamics, management board and practices were seen as interdependent. Performance improvement technology was, therefore, developed with the aim to assist the industry in raising its effectiveness and efficiency. In the same line of thought, Gilbert (1978) suggested performance improvement potential (PIP) as a better human behaviour indicator, in order to replace intelligence, connecting competence development with performance improvement potential.

Nevertheless, psychology was not the only domain competence has prevailed in. In the 1980s, competence-based education (CBE) was introduced in the USA, under the competence movement (Grant et al., 1979) to counteract for the disconnect between the societal needs and education programs. Professional associations started articulating their performance requirements and constructed competence profiles, serving as models for candidates wishing to enter the profession. Educational institutions reformed their curricula, aiming to comply with what was seen as important by professional associations and labour market. The idea dominated the management literature (e.g. Campbell & Sommers Luchs, 1997; Mitrani et al., 1992) and it led to outsourcing of secondary business functions. Interestingly, it had some application in school boards too. Services like competence-based frameworks and tools for competence-based assessment were developed and soon used at all education levels (Mulder, 2001; Mulder, 2017).

The introduction of a functional and pragmatic competence concept in education set the locus on students’ ability to learn (Klieme et al., 2008). Competence is viewed as context specific and functionally related to a particular domain that can be acquired through learning. Competence-based education aimed to teach students how to learn, so they can further gain knowledge on their specialization. Mulder’s (2017) comprehensive summary on the concept has shown that competence mastery can have different levels, also stressed by Barrick (2019) stating the need for differentiating between merely meeting the standards and reaching excellence. Holding a crucial role to effective performance, competence also encapsulates the potential of addressing future problems and needs (Mulder, 2017).

In general, the role of core competence in steering organizations according to what they are good at, as expressed by Prahalad and Hamel (1990) expanded to licensure and professional development. Professional associations redefined their professions through the use of core competencies. Through the management discourse, the competence-based approach was introduced and adopted by Vocational Education and Training (VET) and Human Resource Development (HRD) occupations (Levy-Leboyer, 1996; Stasz, 1997), which were shaped by a demand-driven rather than a supply-driven education model.

Competence has been discussed in several scientific fields. Nevertheless, the bidirectional influence between the everyday concept meanings and the scientific definitions should not be overlooked, making everyday concepts vital in understanding the scientific concepts and vice versa (Vygotsky, 1987). In everyday terms, competence is described as sufficiency of means for life, for example employment, as knowledge, while it also addresses properties that enable an individual to respond, including legal capability, power and fitness, as well as the readiness to undergo transformation (Cambridge Dictionary | English Dictionary, 2019; Collins Dictionary | Definition, 2019; Dictionary by Merriam-Webster, 2019). Reflecting on this definition, two dimensions of the term are identified as crucial. The first addresses the probability, viewing competence as a performance requirement, while the second addresses potentiality viewing competence as licensure. From probability to potentiality, competence is expressed in levels from the minimum to sufficient and successful.

Adding the term professional to the concept of competence frames all this discussion in the context of one particular profession and the demands it sets for the individuals who practice it. The challenge between general knowledge and applied professional knowledge in specific settings is expressed by Abbott (1988) in his definition of professions, which are seen as “exclusive occupational groups applying somewhat abstract knowledge to particular cases” (p. 8). In our case this group is vocational teachers, who as Sullivan (2005) claims, act as “hybrid, bridge institutions with one foot in the academy, so to speak, and one in the world of practitioners” (p. 25).

Methods

Conceptual Analysis Method (CAM)

Concepts are “empirical generalizations, which need to be tested and refined on the basis of empirical research results” (Becker, 1998 as cited in Maggetti et al., 2013, p. 24). Following Becker’s view, concepts are in dialogue with empirical research and, thus, linked to evidence. Conceptual analysis as a scientific method in philosophical research attempts to grasp the logic and nature of the concept to add clarification in scientific research (Schaffar, 2019). On the other hand, in empirically oriented research, it aims at grasping the use of concepts in scientific research to see how the researcher defines and uses the concepts in research (for example Zlatanovic et al., 2016). Reviews of (professional) competence have been performed in the past (a collection of articles in Mulder, 2017; McGrath et al., 2019). However, this study starts from empirical studies with aim to explore the professional competence concept and to relate it specifically with vocational teachers.

Conceptual analysis method (CAM) is applied with the intention of clarifying the various understandings of the professional competence concept and its multiple use. The method elevates the voice of those who use the concept and the power they have to shape it (Tähtinen & Havila, 2018). Focusing on the many interpretations that the concept might acquire, CAM is considered appropriate to discover and elucidate confusion or, as defined by Tähtinen and Havila (2018), the lack of explicit conceptual language. By highlighting the concept’s complexity, it also assists in the deconstruction of different terms and/or concepts, demonstrating their meanings and limits, aiming to contribute in theory building. Reconstructing professional competence is necessary due to the individuals’ tendency of constructing the understanding of theoretical concepts using pre-existing everyday or theoretical concepts, leading to multiple overlapping or contradicting understandings. CAM does not look for one single meaning. Instead, it explores the dimensions of the phenomenon under study, the variety of concept meanings, and the importance of context in its construction (Tähtinen & Havila, 2018).

Methodologically, CAM follows the data collection process of a systematic literature review; however, the focus is solely on concepts, their descriptions or definitions (Tähtinen & Havila, 2018). As in systematic reviews, predefined selection criteria are applied to ensure transparency and avoid subjectivity (Tranfield et al., 2003). Moreover, the criteria are used in searches in electronic databases, aiming to cover a range of journals (Podsakoff et al., 2005). To increase quality, only peer-reviewed articles are included, whereas a broad span of time is used. For this article, the search was conducted in the EBSCOhostFootnote 1 and the Scopus databases. The databases were selected as of relevant content to the profession of vocational teachers.

A timeframe is a vital determination for a quality systematic review (Alexander, 2020). The selected time period ranges from 2010 to 2018. In 2010, OECD released a report stressing the importance of effective VET teachers and trainers as well as emphasizing the lack of qualified workforce in the field and the ageing VET teachers’ population. In the same line of thought, the European Union (2009) published a report about VET teachers and trainers and a year later the Bruges Communique (European Commission, 2010) was released, clearly defining the objectives European Union members had to meet in relation to VET. In all three documents the professional development of VET teachers is deeply related to the quality of VET provision and, therefore, their professional competence becomes of major importance.

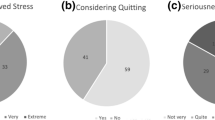

Focusing on professional competence, the search included three keyword searches. The first contained the term professional OR vocational OR occupational, the second was competen* OR skill and the third entailed the phrase vocational teacher. Synonyms were also included and the search was conducted within documents´ keywords and subjects. Only peer reviewed articles published in academic journals were included. Referential backtracking and researcher checking strategy were employed (Alexander, 2020). Figure 1 indicates the results in different phases.

The first assessment was based on abstract relevance. Although the keywords have been carefully selected to refer to the competence that vocational teachers acquire, the search gave results on studies that had a different focus, most often the students’ professional competence and the role of the teachers in developing them. As this type of competence refers to occupational competence of vocational students, it was judged as irrelevant for the study. Reading the abstracts provided sufficient information about the participants and the focus of the study (abstract relevance) (Table 1).

The second assessment concerned text relevance after reading the whole article. In that stage, 51 articles were discarded. The third inclusion criterion was the empirical natureFootnote 2 of the studies presented in the articles (discarding 7 articles). The locus has been on empirical studies, in order to explore the operationalized versions of professional competence and not a philosophical approach to the concept. Aiming to reach the final selection, a quality criterion was introduced, the existence of a definition or a description of the concept under discussion. This criterion left 6 more articles out of the final review body, resulting in 45 articles (see Appendix 1).

Analysis

The selection of the review body was followed by a systematic search for how professional competence is understood and defined, detecting its descriptions and definitions in the articles (for more details see Appendix 2). The analytical process was performed according to the conceptual analysis method (CAM). The description of the five phases follows.

Firstly, while searching for the concept descriptions and definitions, issues of ambiguity arose. Dealing with multidimensional concepts inevitably leads to issues of ambiguity, namely homonymy and synonymy that should be considered. According to Tähtinen and Havila (2018), homonymy refers to the use of the same concept to express different meanings, whereas synonymy addresses the use of multiple concepts to make a reference to the same phenomenon. Ambiguity occurs in scholarly texts, since the concepts and the meanings are usually similar but not the same (Sartori, 2009). For the present study, the researcher did a brief search on the meanings of the terms professional and competence in online dictionaries to detect issues of homonymy and synonymy.

In everyday terms, competence describes “a sufficiency of means for the necessities and conveniences of life”, referring to sufficient resources, that facilitate a decent livelihood. From a linguistic point of view competence also refers to the knowledge of using a language. In addition, competence addresses properties that enable an individual to respond, including legal capability, power, fitness and ability, as well as the readiness to undergo transformation (Cambridge Dictionary | English Dictionary, 2019; Collins Dictionary | Definition, Thesaurus and Translations, 2019; Dictionary by Merriam-Webster, 2019). Competence is, therefore, used to convey a series of different meanings (polysemy), like qualifications or professionalism, and on the contrary many concepts are used to declare competence (synonymy) (e.g. skills, ability, knowledge and competency). Synonymous terms are mainly used to describe the attributes and components of competence.

Secondly, the articles´ text were coded and analysed with the use of the NVIVO software. The articles were coded in two groups, articles that the concept is explicitly defined or implicitly derived (Alexander, 2020). The data was coded under three categories, based on if they presented a definition constructed by the authors, a definition adopted by other scholars or the lack of a congruent definition (but the existence of a description or examples of the concept). This categorization helped answering the question of how the professional competence definition is used in empirical studies of vocational teachers’ competence.

Thirdly, based on the definitions and descriptions discovered, the researcher identified attributes of professional competence that were present in the majority, if not in all the definitions. According to Cambridge Dictionary, attribute is defined as “a quality or feature of a person or thing, esp. one that is an important part of its nature” (2019) and in this study it is used to refer to vital characteristics of this concept. Therefore, attributes and characteristics are used as synonymous. On the other hand, component is applied with reference to parts that combined with other parts constitute a system, process or a machine (Cambridge Dictionary | English Dictionary, 2019). Hence, competence components are mainly knowledge, skills, attitudes and values seen as part of the greater competence notion. On the contrary, attributes refer to the concept qualities (Maggetti et al., 2013). A qualitative content analysis was applied to gasp the wide range of characteristics professional competence is attributed with. The qualitative content analysis is in agreement with the CAM (Holsti, 1969; Neuendorf, 2002) as both underlie an inductive approach to the findings. Applying a qualitative content analysis, the researcher searched for attributes of professional competence within the data.

Fourthly, addressing the question of how the professional competence concept is used, the researcher looked for other concepts associated with professional competence and the purpose of competence in relation to these concepts. The most frequent concepts were selected for further analysis (Sartori, 2009). The researcher identified neighbouring concepts associated to the initial concept, for instance expertise, professionalism and qualifications, “through reflexive and recursive movement between concept development” (Altheide as cited in Bryman, 2012, p. 559). This process allowed for a systematic and analytic approach and avoided a rigid perspective.

As a final step, objective word analysis, as described by Stern (2006), was applied. The researcher identified the most frequently used concepts in the text, which might be linked to the professional competence, and checked their proximity to the concept under study. The purpose of this step was to ensure that the most often encountered concepts have been taken into consideration in the analysis thus, increasing the trustworthiness of the findings.

Findings

The findings of the study are organized and presented corresponding to the research questions. The first part of the findings, namely themes and context answers the question of how the concept definition is used in the literature, focusing on how often it is identified and in relation to which article themes. The two following parts analyse the results on how the professional competence concept is defined. Starting with the main attributes of competence that proved to be shared among all researchers, the focus moves to responsibility, readiness and expertise that are found to be additional attributes for the concept under study. Finally, the final findings section discusses the way that the concept is used, focusing on other concepts that are be related to it.

Themes and Context

In this study, the quality criterion for the existence of a competence definition was adopted in order to investigate how this definition is used in empirical studies. Investigating the articles´ thematologyFootnote 3 was perceived as helpful, aiming to identify the education areas that favour the existence of a definition and those that use the concept vaguely defined.

Deriving from the education area, the articles proved to share similar thematology, with competence development and vocational teacher competence prevailing. A considerable number of studies focused on vocational teacher competence, aiming to either construct competence frameworks or measure existing competencies.Footnote 4 With regard to other themes, the literature covered policy initiatives and their implementation, especially in competence-based education (CBE).

Findings indicated a distinct lack of competence definition in articles that extensively use it. Only a few studies included a clear definition of competence, often borrowed from previous research and serving the purpose of sharing a common understanding with the reader (for more details see Appendix 2). Alternatively, some articles described the concept of competence by referring to its components (knowledge, skills, attitudes, values) (for example see Navarro, Zervas, Gesa and Sampson 2016), which Summers (2001) names as pseudo definitions. The question posed here is whether this type of definition is adequate, having in mind that the competence measurement is in the focus. Young (as cited in Dudung, 2018) claims that when competence measurement is the research aim, the conceptualization process requires high clarification, in order to reach an operational definition structured in a form that facilitates clear measurements.

The majority of the studies included in the review contextualized their research in relation to the changing nature of the profession of the vocational teachers (e.g. Guzanov, Tarasyuk, Bashkova, Ustakova & Sotskova., 2016; O’Connor, 2012), referring to the need for further professionalization either by introducing standards (e.g. Dudung, 2018; Sutarto & Jaedun, 2018), by performing needs assessment (e.g. Barrick, et al., 2011; Sartori, Tacconi & Caputo, 2015) or by evaluating the implementation of policy measures (Alazzam, Bakar, Hamzah & Asimiran, 2012; Andersson, Hellgren & Köpsén, 2018). Very few articles framed competence in relation to the national education systems (Barrick et al., 2011; Köpsén & Andersson, 2017; Poortman et al., 2011). Instead, they adopted an approach where reference is made to national and international studies about vocational teachers, whether with a more general or a more discipline oriented focus. That does not mean, though, that the competence definitions in the studies were not contextualized.

Some studies contextualized their definitions in the theoretical approaches adopted. For example, competence based education is the most frequent among these article (e.g. Guzanov et al., 2016; Malik, Soenarto & Sudarsono, 2018; Neupokoeva et al., 2017; Nissilä et al., 2015; Southren, 2015), while situated learning is also often encountered (Andersson, Hellgren & Köpsén, 2018; Andersson & Köpsén, 2017; Köpsén, 2014; Köpsén & Andersson, 2017; Poortman et al., 2011). Other theories includes Teacher Adaptive Expertise (Barrick et al., 2011), Effective Teaching (Adams, 2010) and Authentic Assessment (Sutarto & Jaedun, 2018).

Based on the two more frequently encountered theoretical approaches, the difference noted in the conceptualization of competence is in relation to tasks and, thus, standards or in relation to roles. From a fist read, this does not relate to the VET system, but mostly to the aim of the article. On a second read, though, it can be said that the system affects the way research is directed and the epistemological approaches dominant in it.

It would be expected that the competence understanding is affected by the different VET systems and the different teacher needs; nevertheless, the articles in the review do not offer enough information to draw this conclusion.

Finally, authors seem to be consistent with the use of competence and competency, applying the first as a general umbrella notion and then later to describe a specific ability or behaviour. Instead of competence and competency, skill is often present, but to a lesser extent.

The Attributes of Competence

In their attempt to understand professional competence, most authors share an agreement on some attributes. Firstly, competence is approached as a concept that receives its meaning in relation to the context (Grønborg, 2013). Although there seems to be a core of competence that all authors share, the definitions are contextualised and developed in relation to an external point of reference, for instance standards, expert professionals, or work-related characteristics. Adamoniene et al. (as cited in Adomaitienė & Zubrickienė, 2010, p. 88) claim that competence has a subjective character and it is used to characterize a professional and his or her ability to accomplish a task or make responsible decisions on the basis of his or her obligation to their role. Therefore, competence is seen in relation to predefined obligations determined by the position of the individual professional (Malik, Soenarto & Sudarsono, 2018; Wu, Huang, Kao, Lue & Chen, 2018). That practically means that a vocational teacher can be judged as competent only in relation to the obligations he or she has been assigned with.

Nevertheless, Adomaitienė and Zubrickienė (2010) defined competence also in relation to an internal point of reference, which in this case is the individual. Addressing the idea that competence is adopted, in order to provide us with the “characterization of a person” (ibid, p. 88–89), the onus is moved from the system to the individual that is now constructed as an entity through their competence. This is in alignment with a common response to the question who someone is, highlighting the link between everyday and scientific language (Vygotsky, 1987). When describing another person, people usually refer to his/her name, gender and profession, using formal competence to define identity.

Secondly, competence is learnable; this is referred to as competence development or competence acquisition. Some authors (Adomaitienė & Zubrickienė, 2010; Dorozhkin et al., 2016; Falco, Fedorov, Dorozhkin, Merkushova & Bakanachet, 2016; Malik, Soenarto & Sudarsono, 2018; Sartori, Tacconi & Caputo, 2015; Wu et al., 2018) include this quality of competence in their definitions. More specifically, perceiving competence as capability, Sartori et al. (2015, p. 26) refer to McCleeland and Nuthall stating that “Competencies can be learned (McClelland, 1973; Nuthall 1999). That is the reason why they tend to be taught through education and training activities”. According to this quote, competence can be learned, therefore it can also be taught. The use of the phrase “tend to be taught” refers to formal learning processes, where competence development is the goal. The same approach is adopted by Casey (as cited in Wu et al., 2018) and Malik, Soenarto and Sudarsono (2018). In this case, competence is seen as a learning outcome, the result of a learning process.

While constructing a competence profile for development agentsFootnote 5 in Ethiopia, Tarekegne, Wesselink, Harm, Biemans and Mulder (2017) adopt Mulder’s competence definition (2001, p. 152) that brings together the characteristics discussed above:

competence is the integrated performance-oriented capability of a person or an organization to reach specific achievements. These capabilities consist of clusters of knowledge structures and cognitive, interactive, affective and where necessary psychomotoric skills, attitudes, and values, which are conditional for carrying out tasks, solving problems and effectively functioning in a certain profession, organization, position and role.

Mulder’s definition refers to reaching specific achievements, being in agreement with Adamoniene et al. (as cited in Adomaitienė & Zubrickienė, 2010) for the existence of some predefined tasks and/or outcomes that an individual possessing a competence needs to be able to achieve. The definition also recognizes the developmental character of competence, as well as its situated nature. Finally, by referring in detail to the wide range of competence components, the definition achieves a holistic conceptualisation.

Thirdly, competence is strongly associated with action. In some studies, action is a component of competence. As Khutorskoi (as cited in Neupokoeva et al., 2017, p.1395) points out, competence is a set of individual qualities including skills, knowledge, abilities and methods of action “assigned referring to a definite range of things and processes and necessary for a qualitative productive activity with regard to them”. Adding a slightly different perspective, Andryukhina et al. (2016a, p. 7022) citing Marshuba address competence as “a human ability to mobilize the knowledge and skills in the course of professional activities”, highlighting that the interaction between the individual and their surroundings is an indispensable aspect of developing, enacting and practicing competence (Falco et al., 2016; Fedulova, Fedulova, Kirillova, Vagina & Kuznetsov, 2017). The same definition, supported by other researchers (Tarekegne et al. 2017; Wu et al. 2018), demonstrates an important precondition for competence activation, which is the framework of professional practice.

In addition, a central approach between action and competence suggests that competence is expressed through action (Marshuba as cited in Andryukhina et al., 2016a; Khutorskoi as cited in Neupokoeva et al., 2017; Sudirman, 2017). Consequently, since the existence of competence is acknowledged through action, the measurement of action leads to the measurement of competence.

Mapping the use of adjectives, competent and capable, as synonymous to the idea of competence, they are found to be often used but not defined. Hence, it is supposed that the researchers adopt the meanings the words get in everyday use. Sudirman (2017, p.114) refers to teacher competency standards as a set of capabilities for “a decent education personnel so-called competent”, showing that decent and competent are synonymous. On the other hand, Poortman, Illeris and Nieuwenhuis (2011, p. 267) provide a more clear understanding presenting competent as the third stair in a scale from advanced beginner to expert (“novice”, “advanced beginner”, “competent”, and “proficient” to “expert”), a model originally developed by Dreyfus and Dreyfus (1980). A capable or a competent professional can be defined as the one who meets the formal standards or as the one who corresponds to the specific needs of a given working environment. Even when specific competencies are discussed in an article (for example Schmidt, 2017), the imprecise use of competent might lead to confusion regarding the degree to which the competency is acquired or naturally possessed.

Responsibility, Readiness and Expertise

Competence components include knowledge, skills, attitudes and values for the majority of the scholars. A consensus is reached over this aspect of the concept. However, in connection to vocational teachers, three other concepts are widely discussed, responsibility, readiness and expertise. Competence has been connected with responsibility (Roth, 1971), readiness and expertise (Mayer, 2003) in the past as well.

Responsibility is mentioned as a main component of professional competence. It is not perceived as a fundamental part of competence, but as substantial element of professionalism. Responsibility refers to the obligation one has to meet the formal standards set for the profession (Gridnevа, Vasyakin, Ovsyanik, Pozharskay & Berezhnaja, 2017). Sometimes it is used in plural, responsibilities (Adams, 2010; Piskunova, Sokolova & Kalimullin, 2016; Smith & Yasukawa, 2017), to address the tasks a professional has to perform and outlining the importance of preforming these tasks in order to be considered professional.

Readiness, also expressed as preparedness, is often found in the articles. Both concepts seem to attempt to describe the gap between education and employment and how this can be bridged by gaining competence (Andryukhina et al., 2016a/2016b; Piskunova et al., 2016; Saimbetova, Sarbassova, Mukhtarova, Bekmagambetov & Kaltayeva, 2017; Stephens, 2015; Wu et al., 2018). Through their literature review, Falco et al. (2016, p. 9267) conclude that competence is a “system of knowledge and skills, providing readiness to perform professional activities, while competency is an integrity (group of interrelated and interdependent) of knowledge, skills, experience and personal qualities enabling successful implementation of professional activities in the specific field” (emphasis by the author). Furthermore, Alazzam et al. (2012) present Inan and Lowther’s definition of teachers’ readiness as their perceptions of their own capabilities and skills required, in order to integrate technology in teaching. In their understanding, readiness is a state of self-awareness combined with the ability for needs assessment. Further, in their study, they measure readiness in terms of knowledge, skills, and attitudes, allowing the assumption that readiness is competence. Finally, addressed as preparedness by Piskunova et al. (2016), readiness for professional activity is perceived as the “ability to carry out responsibilities in specific problematic situations” (Tokareva as cited Piskunova et al., 2016, p.1004). It is, therefore, an integrated set of cognitive, functional and personal competencies that constitute the professional competence of readiness (Nazarov as cited Piskunova et al., 2016).

Expertise is also discussed as part of the professional competence of vocational teachers (Duch & Andreasen, 2017; Esmond & Wood, 2017; Falco et al., 2016; Redmond, 2017). Levels of expertise, or levels of competence acquisition, are discussed and/or mentioned in nearly all the articles that contain a definition. As discussed above, the issue of expertise, as well as confusion related to the degree to which individuals can acquire competencies are core issues in defining and understanding competence. Nevertheless, no article engages in further discussion.

Within their scale of competence, ranging from “novice,’ “advanced beginner,” “competent,” and “proficient” to “expert” (Poortman et al., 2011, p. 267), experts are defined as possessing a rich base of experience and have obtained the necessary amount of quality knowledge as well as the ability to perform routines efficiently in their field. Expertise is approached as a feature that professionals achieve after years of professional experience and after the development of competencies that can actually be observed.

Guzanov et al. (2016) highlight the connection between capacity building and developing professional expertise, suggesting that the former can foster the latter. This means that researchers may observe such expertise through observing competence. The relation between the two concepts, expertise and professional competence, is not the only one that implies that professional development results in better quality professional competence. Performance, qualifications and professionalism are similar cases.

Competence and Professionalism: Professionalization, Professional Identity and Professional Competence

Exploring how the professional competence concept is used in the articles, it becomes obvious that many authors relate it with other concepts, like professionalism, performance and qualification. However, these concepts are not synonymous to professional competence, but often used as such. These terms usually indicate relationships between the existence of competence and the facilitation of the related concept.

Professional competence is thoroughly linked to performance, responsibility and effectiveness, especially with reference to the public perception. Evidence of performance is expected to exist for a professional to be seen as competent (Amiartuti & Endang, 2015; Attaochu, 2013; Falco et al., 2016; Sartori et al., 2015; Southren, 2015; Sudirman, 2017; Tambunan, 2014; Tarekegne et al., 2017; van Dam, Schipper & Runhaar, 2010). This evidence is considered in relation to professional standards which serve often as a reference point for individuals to compare and evaluate their professional level and the professional levels of others. In other words, it allows others and the individual to define themselves or others as having adequate competence. As defined by Mulder (2014, p.3), “professional competence is seen as the generic, integrated and internalized capability to deliver sustainable effective (worthy) performance (including problem solving, realizing innovation, and creating transformation) in a certain professional domain, job, role, organizational context, and task situation.” . The idea that performance is the actualization of competence is also present in earlier literature (Klieme et al., 2008).

The studies focusing on professional competence as qualification expressed and measured through standards often refer to international organizations such as those of OECD, ETF (Esmond & Wood, 2017) and CEDEFOPFootnote 6 or the respective education ministries and their definition of competence (Andryukhina et al., 2016a/2016b; Dudung, 2018; Manley & Zinser, 2012; Schmidt, 2017; Sudirman, 2017). Qualifications address certified professional competence. Therefore, professional competence has already been measured, as it corresponds to a specific (standard) level and it has been formally tested and evaluated. Because of this, it is important to also raise questions in relation to power and agency in determining standards and qualifications (Wu et al., 2018). Since this is part of a long discussion, the present study is limited to making the following point. Competence is defined by several stakeholders; hence, their interests and intentions are reflected within the concept. The variety of meanings that the term has been given over the years allows political interests to remain hidden. Therefore, the definition these organizations attribute to professional competence is portrayed as one more in the wide range of competence meanings. But is it only as such?

Based on the findings of this review, vocational teacher professionalism can be summarized with reference to participation in practice, up to date knowledge basis (also in relation to the initial occupation), awareness of the legal aspects of work as well as of the working culture, teaching skills, self-development attitude, humanistic values and responsibility and accountability (Adams, 2010; Wu et al., 2018). Adams´ (2010) and Dudung´ s (2018) studies approached and discussed professionalism in relationship to standard frameworks for vocational teachers. Both presented professionalism, or professional competence as one of the competence areas included in the standards framework for vocational teachers. They described it as mastery of the subject area and as reflection, while they separated it from other competence areas, like social and pedagogical competence. Professionalism in that sense relates with only some aspect of vocational teachers work and more specifically, it seems to correspond to vocational knowledge and didactics and the reflective practice. Schön (1987) gave prominence to reflection and its importance for educators through his concept of the reflective practitioner.

Scandinavian studies focusing on vocational teachers´ identity formation have defined professionalism with reference to both their vocational and teacher background. Individuals possess a variety of identities within the workplace, which are linked to how they and others view their competence. Professional identity formation and dual professionalism are common patterns, when competence is discussed (Andersson, Hellgren & Köpsén, 2018; Andersson & Köpsén, 2017; Köpsén, 2014; Köpsén & Andersson, 2017; Redmond, 2017). The professional competence of vocational teachers consists of their initial vocational/occupational identity and their teacher identity formulated in a second stage.

Nevertheless, the most extensive discussion on the relationship between competence and professional practice is found in Tarekegne et al. (2017). Their study uses a holistic conceptualization of competence as quoted above in the section “The attributes of competence”. Referring to Mulder’s previous work (2014) there is a distinction of competence definitions based on their relationship with the professional practice. Adopting situated professionalism, professional competence is perceived as influenced by the context and the particular interactions occurring there.

Approaching the element of professionalism firstly as a competence area, secondly as connected to roles and identities and thirdly as highly influenced by the context, suggests a variety of interpretations. The differences between these understanding are fundamental and can further affect the operationalization of professional competence and, hence, its capturing.

Finally, the concepts of professionalism, professional identity and expertise are not synonymous to professional competence. Nevertheless, they encompass professional competence, but they require other aspects of the individual to be developed, in order to be rendered achieved. For example, expertise addresses competence not only acquired, but also practiced and implemented in an advanced level. Yet, all three constructs are often confused with professional competence and this affects the discussion around it.

Discussion

By applying a conceptual analysis, this review explores the definition and use of the concept of professional competence in empirical studies focusing on vocational teachers. Based on the findings, there is an agreement among the researchers on the components (knowledge, skills, attitudes, values) and the main attributes of professional competence. These attributes include the situated and developmental character of professional competence as well as its relation with action. With regard to the concept use, there are distinct interrelationships between professional competence, professionalism, performance and qualification. In this section, professional competence is discussed as a complex concept and some of the aspects affecting its definition formation are addressed.

The variety of the disciplines adopting the competence concept highlights its significance and functionality. Reflecting both on the findings and the historical development of the concept, it becomes apparent that different disciplines have been in need of a complex ‘tool’ that will facilitate the conceptualization of knowledge, intelligence, performance and skills, allowing their observation, measurement and studying. The professional competence concept seems to meet these demands in vocational teacher research as well.

The concept of professional competence can be perceived as a complex concept, which cannot be easily defined (Engeström et al., 2006). There is usually extensive effort to stabilize complex concepts even temporarily (Smith, 1996). In addition, a complex concept’s understanding is better facilitated, when studied in relation to its historical evolution. Professional competence of vocational teachers seems to meet these traits, especially when reviewing the efforts for defining it, the lack of unanimity and the various meanings it receives among different scientific disciplines. In the same line of thought, professional competence is a dynamic concept, constructed and reconstructed by various stakeholders and in different contexts (Engeström et al., 2006), which results in a wide range of definitions that set locus to different points. The task variation of vocational teachers supports this multifaceted approach, since the concept defining their competence is operationalized differently. This becomes quite apparent by comparing definitions from national bodies, like ministries, with those of researchers. Who defines the concept is crucial, in what context and why the concept is addressed as well.

Professional competence definitions are future oriented, since they bring up issues of authority and legitimization, highlighting the tendency for control. The future orientation is attributed to the general concept of competence as well (Schaffar, 2019). More specifically, Illeris´ competence definition (2013, p.38) includes qualities like “flexibility”, suggesting that the concept expresses the need for propensity for change. In the case of vocational teachers, this is usually apparent with recommendations about measuring teacher competence or improving their performance.

Moving to the nature of the concept, professional competence is seen as a set of knowledge, skills, values and attitudes that exist as a potential in individuals. They are activated under specific circumstances, actualized, shaped and developed moving from potential to fully developed and performed abilities. The concept’s attributes are shared by the authors, as they agree on the situated and developmental nature of the concept, as well as its relation to action or activity. While an agreement stands for the components and attributes of the concept of competence, there is a wide variation about the meaning of professional, where the confusion stems from. As Roth (as cited in Klieme et al., 2008) stressed professional refers to the ability to act responsibly in a specific profession. Nevertheless, defining what the profession demands can be influenced by focusing on the context or the individual.

When the locus of the definition is situated more on the context (workplace or national qualifications), differences emerging derive from the type and ideology of the workplace and the particular traits of the profession in a specific country. Focusing on the context, professional competence is approached in an intuitive-contextual perspective (Ellström, 1997). Learning and, thus, competence development is seen as situated, experience based and related to action. Without the context, competence is not professional, it is simply an ability and it cannot be developed as it has no point of reference. Once developed, this competence is strongly related to the context, whether this is a workplace, or a national context.

On the contrary, there is a cognitive rational perspective (Ellström, 1997) indicating that theory has also an important role to play in professional competence development and, hence, formal education leading to qualifications is necessary too. The focus here moves form the context to the individuals and the things they can do, especially highlighting the possibility of measuring and quantifying their performance. Such a perspective still supports the developmental character of competence and its relation to action, but lowers the significance of situatedness.

The attribute of situatedness contributes to multiple definitions. According to Wittgenstein (1999), we easily get confused, when a concept has different uses and, hence, we seek for the “correct definition” that can exist independently of a particular context. In research, the quest for such an unambiguous definition has an additional purpose, the aim for empirically measurable data. This approach is obvious in the data as several empirical studies lack a complete concept definition, although they pursue its measurement. It is crucial to remember that such a definition should be adjusted to each study based on the target population and the research questions.

Concept definition and operationalization is crucial before measurement (Maggetti et al., 2013). The concept definition, seen in relation to the measurement for concept, assists the reader to make a judgement on the construct validity of the study. This is particularly important for concepts surrounded by high confusion. Defining a concept solely through measurement, and hence without a definition, does not allow the reader to have a complete understanding of the researchers´ construct definition and understanding. Therefore, the lack of definition limits the ways that research can be further used, for example be replicated, re-measure the same concept or be used as a basis for theory building. Consequently, the understanding of the operationalized version of the concept has been judged to have a key role both in facilitating future studies and in clarifying the concept in general.

Notwithstanding, as learnable and related to action, competence is thoroughly linked to the individual. Therefore, the individual is the initiator of any understanding and has direct access to the shared image of competence attributes. Professional competence is an everyday concept shaped by all individuals and the interaction among them. In this process, the individual is an originator and transmitter of the concept understanding, but also the receiver of the meanings constructed, after other stakeholders, like the labour market, the research community and the state, process the concept. In the end, the individual remains an agent in the construction of their personal understanding. Irrespective of the concept’s external definitions, the individual holds an important role in developing their own understanding of professional competence and more importantly acting towards its realization (Billett, 2001; Tynjälä, 2013).

Limitations, Implications and Future Research

This study has several delimitations set by the researcher, since a literature review of the term competence would give many results with very different ontological attributes (Alexander, 2020; Maggetti et al., 2013). As indicated in the method, the data is limited to empirical studies that attempt to grasp the competence of vocational teachers. These studies are neither theoretical nor conceptual discussions and, therefore, it is expected to not have extended discourses over the concept. This creates a limitation. As the studies have an empirical focus, concepts might be ignored for pragmatic reasons.

As MacKenzie (2003) claims, concepts are the building blocks of theory. Therefore, their poor construction may lead theory development towards a different direction than the intended one provoking more confusion. Clarifying concepts before performing measurements can also reduce bias (Maggetti et al., 2013). In agreement with this idea, this article provides space for review and reflection of a core concept in VET, the professional competence of vocational teachers, and renders for better definition before its application and measurement. By bringing together the different definitions and understandings, the author provides the context for a dialogue between them, a dialogue that is a first step to theory development and the achievement of conceptual clarity.

Besides contributing to the clarification of the concept, the present study suggests a respective methodology to achieve it. The Conceptual Method Analysis (CAM) has not been widely used and, therefore, this study contributes in its examination as a research tool, demonstrating strong or weak aspects for future researchers to consider. CAM facilitates the concept deconstruction and the detection of the concepts origins in helpful way. In that sense, it highlights the roots of the confusion and the expected preconceptions behind specific conceptualizations. In addition, it assists the better understanding of the relationships between concepts. With reference to professional competence, however, CAM provided limited support in addressing a key dimension of the concept, the levels of competence. Nevertheless, the complex nature of the concept may require setting the competence levels in the locus of CAM to answer the question mentioned above.

The situated nature of competence emphasises the difficulty of generalizing from a context to another, especially for vocational teachers. As their competence is context bound, special attention should be given to the respective context, where the competence is developed and activated. Furthermore, the variety of the VET systems calls for additional attention to the systems´ structure and dynamics, when competence is contextualized, operationalized and measured. A comparative approach on the concept’s operationalization, either among VET systems or among occupations could assist further in unravelling the importance of the context.

As a final point of reflection that relates both to the methods and the concept meaning, the importance of the language needs to be acknowledged. As indicated also by Schaffar (2019), since the context has proven to have a major role in the definition and the concept development, language and the cultural environment where the concept is used may influence the understanding to a large extent. Further studies, adopting a linguistic and sociocultural perspective can shed more light on the issue.

Change history

01 December 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-021-09281-5

Notes

EBSOhost database include the following databases for this study: Academic Search Premier, OpenDissertations, ATLA Religion Database, Business Source Premier, CINAHL, Communication & Mass Media Complete, Communication Abstracts, Criminal Justice Abstracts, eBook Collection (EBSCOhost), EconLit, ERIC, Fuente Académica Premier, GreenFILE, Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts, MathSciNet via EBSCOhost, MEDLINE, Philosopher’s Index, Regional Business News, RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, Sociology Source Ultimate, MLA Directory of Periodicals, MLA International Bibliography.

For this article, empirical refers to studies that analyse primary data, excluding secondary data analysis, metanalyses or literature reviews.

Thematology is the study of themes in the literature. Here it refers to the mapping of the different themes on which the articles in the reviewed literature are focused.

for example Barrick, Roberts, Samy, Thoron & Easterly, 2011; Cannon, Kitchel & Duncan, 2010; Danielová, Janderková & Horáčková, 2011; Dorozhkin, Tarasyuk, Lyzhin, Krotova & Sherstneva, 2016; Neupokoeva, Chapaev, Chubarkova, Tolstova, Fedulova & Tokar, 2017; Nissilä, Karjalainen, Koukkari, & Kepanen, 2015; O’Connor, 2012; Ramadan, Chen & Hudson, 2018; Sutarto & Jaedun, 2018; van Uden, Ritzen & Pieters, 2013

Development agents are employed by the university agricultural departments to offer capacity development for farmers. They provide training and advisory services.

OECD: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, ETF: European Training Foundation, CEDEFOP: European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training

References

Abbott, A. (1988). The system of professions: An essay on the division of expert labor. University of Chicago Press.

Adams, E. (2010). A framework for the preparation of accomplished career and technical education teachers. Journal of Career and Technical Education, 25(1), 21–34

Adomaitienė, J., & Zubrickienė, I. (2010). Career competences and importance of their development in planning of career perspective. Bridges / Tiltai, 53(4), 87–99

Alazzam, A.-O., Bakar, A.-R., Hamzah, R., & Asimiran, S. (2012). Effects of demographic characteristics, educational background, and supporting factors on ICT readiness of technical and vocational teachers in Malaysia. International Education Studies, 5(6), 229–243. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v5n6p229

Alexander, P. (2020). Methodological guidance paper: The art and science of quality systematic reviews. Review of Educational Research, 90(1), 6–23.

Amiartuti, K., & Endang, S. (2015). Teacher performance of the state vocational high school teachers in Surabaya. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE), 4(2), 76–83. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijere.v4i2.4495

Andersson, P., Hellgren, M., & Köpsén, S. (2018). Factors influencing the value of CPD activities among VET teachers. International Journal for Research in Vocational. Education and Training, 5(2), 140–164. https://doi.org/10.13152/IJRVET.5.2.4

Andersson, P., & Köpsén, S. (2017). Maintaining competence in the initial occupation: Activities among vocational teachers. Vocations and Learning, 11(2), 317–344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-017-9192-9

Andryukhina, L. M., Dneprov, S. A., Sumina, T. G., Zimina, E. Y., Utkina, S. N., & Mantulenko, V. V. (2016a). The model of monitoring of vocational pedagogical competences of professors in secondary vocational education. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 11(14), 7016–7034

Andryukhina, L. M., Dneprov, S. A., Sumina, T. G., Zimina, E. Y., Utkina, S. N., & Mantulenko, V. V. (2016b). Vocational pedagogical competencies of a professor in the secondary vocational education system: Approbation of monitoring model. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 11(14), 7045–7065

Attaochu, E. U. (2013). Quality assurance of teachers in the implementation of the curriculum of technical and vocational education in colleges of education (technical) in north central Nigeria. In International Journal of Adult Vocational Education and Technology, 4(2), 34-43. Global

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215.

Barabasch, A. (2017). Quality management of competence-based education. In M. Mulder (Ed.), Competence-based vocational and professional education. Bridging the world of work and education (pp. 649–666). Springer International Publishing Switzerland.

Barrick, R. K. (2019). Competence and excellence in vocational education and training. In S. McGrath, M. Mulder, J. Papier, & R. Suart (Eds.), Handbook of vocational education and training (pp. 1155–1166). Springer Nature Switzerland.

Barrick, R. K., Roberts, T. G., Samy, M. M., Thoron, A. C., Easterly, R. G., & III. (2011). A needs assessment to determine knowledge and ability of Egyptian agricultural technical school teachers related to supervised agricultural experience. Journal of Agricultural Education, 52(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2011.02001

Billett, S. (2001). Learning through work: Workplace affordances and individual engagement. Journal of Workplace Learning, 13(5), 209–214.

Campbell, A., & Sommers Luchs, K. (1997). Core competency-based strategy. International Thomson Business Press.

Campbell, A., & Sommers Luchs, K. (1997). Core competency-based strategy. International Thomson Business Press.

Cannon, J., Kitchel, A., & Duncan, D. (2010). Identified perceived professional development needs of Idaho secondary CTE teachers: Programme management needs of skilled and technical science teachers. Journal of STEM Teacher Education, 47(1), 42–69

Danielová, L., Janderková, D., & Horáčková, M. (2011). Analysis of educational needs of student teachers at the Institute of Lifelong Learning at Mendel University in Brno. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis, 59(7), 97–104. https://doi.org/10.11118/actaun201159070097

Dorozhkin, E. M., Tarasyuk, O. V., Lyzhin, A. I., Krotova, O. P., & Sherstneva, N. L. (2016). Structural and functional model of training future masters of vocational training for the organization of teaching and the production process in terms of networking. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 11(15), 8323–8334

Dreyfus, S. E., & Dreyfus, H. L. (1980). A five-stage model of the mental activities involved in directed skill acquisition. Storming Media.

Duch, H., & Andreasen, K. E. (2017). VET Again: Now as a VET teacher. International Journal for Research in Vocational. Education and Training, 4(3), 289–305. https://doi.org/10.13152/IJRVET.4.3.6

Dudung, A. (2018). Competency test result of vocational school teacher’s majoring light vehicles subject in East Jakarta. AIP Conference Proceedings, 1941(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5028064

Ellström, P. (1997). The many meanings of occupational competence and qualification. Journal of European Industrial Training, 21(6/7), 266–273.

Engeström, Y., Pasanen, A., Toiviainen, H., & Haavisto, V. (2006). Expansive learning as collaborative concept formation at work. In K. Yamazumi, Y. Engeström, & H. Daniels (Eds.), New learning challenges: Going beyond the industrial age system of school and work (pp. 47–77). Kansai University Press.

Esmond, B., & Wood, H. (2017). More morphostasis than morphogenesis? The “dual professionalism” of English further education workshop tutors. Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 69(2), 229–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2017.1309568

European Commission. (2010). The Bruges communiqué on enhanced European cooperation in vocational education and training for the period 2011–2020. Retrieved from http://www.elgpn.eu/elgpndb/fileserver/files/49. Accessed 15 January 2018.

European Union. (2009). Teachers and trainers in vocational education and training: Outcomes of four peer learning activities. Retrieved from http://www.kslll.net/Documents/EAC_B5_general_brochure_280909_web_en-electronic%20version.pdf. Accessed 18 March 2020.

Falco, V. P., Fedorov, V. A., Dorozhkin, E. M., Merkushova, N. I., & Bakanach, O. V. (2016). Forming artistic-design competency of vocational design teacher. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 11(16), 9266–9284

Fedulova, K., Fedulova, M., Kirillova, Y., Vagina, A., & Kuznetsov, T. (2017). Special competence in the structure of vocational pedagogical integrity in the sphere of vocational education. Eurasian Journal of Analytical Chemistry, 12(7b), 1265-1273. https://doi.org/10.12973/ejac.2017.00252a

Fejes, A., & Köpsen, S. (2014). Vocational teachers’ identity formation through boundary crossing. Journal of Education and Work, 27(3), 265–283.

Gilbert, T. F. (1978). Human competence. Engineering worthy performance. McGraw-Hill.

Grant, G., Elbow, P., Ewens, T., Gamson, Z., Kohli, W., Neumann, W., Olesen, V., & Riesman, D. (1979). On competence. A critical analysis of competence-based reforms in higher education. Jossey-Bass.

Gridnevа, S., Vasyakin, B., Ovsyanik, O., Pozharskay, E., & Berezhnaja, M. (2017). Modern health improving psychotechnologies of a higher school teacher’s personality. Eurasian Journal of Analytical Chemistry, 12(5b), 823-834. https://doi.org/10.12973/ejac.2017.00214a

Grønborg, L. (2013). Scaring the students away? Institutional selection through assessment practices in the Danish vocational and educational training system. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 1(18), 507–524.

Guzanov, B. N., Tarasyuk, O. V., Bashkova, S. A., Ustakova, D. A., & Sotskova, S. I. (2016). The structural and functional model of development of profession-oriented and specialized competences of students at vocational and pedagogical higher educational establishments. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 11(16), 9222–9238

Holsti, O. R. (1969). Content analysis for the social sciences and humanities. Addison-Wesley Pub.

Illeris, K. (2013). Kompetens:Vad, varför, hur. Studentlitteratur.

Klieme, E., Hartig, J., & Rauch, D. (2008). The concept of competence in educational contexts. In J. Hartig, E. Klieme, & D. Leutner (Eds.), Assessment of competencies in educational contexts (pp. 3–22). Hogrefe & Huber Publishers.

Köpsén, S. (2014). How Vocational teachers describe their vocational teacher identity. Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 66(2), 194–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2014.894554

Köpsén, S., & Andersson, P. (2017). Reformation of VET and demands on teachers’ subject knowledge - Swedish vocational teachers’ recurrent participation in a national CPD initiative. Journal of Education and Work, 30(1), 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2015.1119259

Levy-Leboyer, C. (1996). La gestion des compétences. Les Editions d’Organisation.

MacKenzie, S. B. (2003). The dangers of poor construct conceptualization. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 31(3), 323–326.

Maggetti, M., Gilardi, F., & Radaelli, C. M. (2013). Conceptual analysis. In M. Maggetti, F. Gilardi, & C. M. Radaelli (Eds.), Designing research in the social sciences (pp. 21–41). SAGE Publications Ltd..

Mahlamäki-Kultanen, S., Susimetsä, M., & Ilsley, P. (2006). Valorisation project: The changing role of VET teachers and trainers. Centre for International Mobility CIMO, Finnish Leonardo National Agency.

Malik, M., Soenarto, S., & Sudarsono, F. (2018). The competency-based training model for vocational high school teachers from electrical expertise programs. Jurnal Pendidikan Vokasi, 8(3), 313–323. https://doi.org/10.21831/jpv.v8i3.19877

Manley, R. A., & Zinser, R. (2012). A Delphi study to update CTE teacher competencies. Education & Training, 54(6), 488–503. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911211254271

Mayer, R. E. (2003). What causes individual differences in cognitive performance. In R. J. Sternberg & E. L. Grigorenko (Eds.), The psychology of abilities, competencies, and expertise (pp. 263–273). Cambridge University Press.

McClelland, D. (1973). Testing for competence rather than for ‘intelligence’. American Psychologist, 28(1), 1–14.

McGrath, S., Mulder, M., Papier, J., & Suart, R. (2019). Handbook of vocational education and training. Springer Nature Switzerland.

Mitrani, A., Dalziel, M., & Fitt, D. (1992). Competency based human resource management. Kogan Page.

Mulder, M. (2001). Competence development – Some background thoughts. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 7(4), 147–159.

Mulder, M. (2014). Conceptions of professional competence. In S. Billett, C. Harteis, & H. Gruber (Eds.), International handbook of research in professional and practice-based learning (pp. 107–137). Springer.

Mulder, M. (2017). Competence Theory and Research: a synthesis. In: Mulder. M. (Ed.), Competence-Based Vocational and Professional Education. Bridging the Worlds of Work and Education. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, pp. 1071–1106.

Navarro, S. B., Zervas, P., Gesa, R. F., & Sampson, D. G. (2016). Developing teachers’ competences for designing inclusive learning experiences. Educational Technology & Society, 19(1), 17–27

Neuendorf, K. A. (2002). The content analysis guidebook. Thousand oaks. Sage publications.

Neupokoeva, E., Chapaev, N., Chubarkova, E., Tolstova, N., Fedulova, K., & Tokar, A. (2017). Peculiarities of preparation of a vocational teacher for use of application software taking into account the requirements of the Federal State Education Standard. Eurasian Journal of Analytical Chemistry, 12(7b), 1383-1398. https://doi.org/10.12973/ejac.2017.00265a

Nissilä, S-P., Karjalainen, A., Koukkari, M., & Kepanen, P. (2015). Towards competence-based practices in vocational education - What will the process require from teacher education and teacher identities? Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal, 5(2), 13-34

O’Connor, P. J. (2012). The Professional development needs of academic teachers adding career-technical education licenses. Journal of Career and Technical. Education, 27(1), 34–47. https://doi.org/10.21061/jcte.v27i1.538

OECD. (2010). Learning for jobs, synthesis report of the OECD reviews of vocational education and training. OECD.

Piskunova, E., Sokolova I., & Kalimullin, A. (2016). The problem of correspondence of educational and professional standards (results of empirical research). International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 11(6), 1003-1010. https://doi.org/10.12973/ijese.2016.509a

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Bachrach, D. G. (2005). The influence of management journals in the 1980s and 1990s. Strategic Management Journal, 26(5), 473–488.

Poortman, C. L., Illeris, K., & Nieuwenhuis, L. (2011). Apprenticeship: From learning theory to practice. Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 63(3), 267–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2011.560392

Pottinger, P. S., & Goldsmith, J. (Eds.). (1979). Defining and measuring competence. Jossey-Bass.

Prahalad, C.K. & G. Hamel (1990). The core competence of the corporation, Harvard Business Review, May–June, 79–91.

Ramadan, A., Chen, X., & Hudson, L. L. (2018). Teachers’ skills and ICT integration in Technical and Vocational Education and Training TVET: A Case of Khartoum State-Sudan. World Journal of Education, 8(3), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.5430/wje.v8n3p31

Redmond, P. (2017). VET practitioner’s perceptions of VET higher-education qualifications. International Journal of Training Research, 15(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/14480220.2017.1313170

Roth, H. (1971). Pädagogische Anthropologie (Vol. 2). Schroedel.

Saimbetova, Z. Sarbassova, K., Mukhtarova, S. M., Bekmagambetov, A., Kaltayeva, G. (2017). Competence approach to developing ethical-cultural personality of future teachers of vocational training. Man in India, 97(6), 327-344. Serials Publications

Sartori, G. (2009). Guidelines for concept analysis. In D. Collier & J. Gerring (Eds.), Concepts and method in social science. The tradition of Giovanni Sartori (pp. 97–150). Routledge.

Sartori, R., Tacconi, G., & Caputo, B. (2015). Competence-based analysis of needs in VET teachers and trainers: An Italian experience. European Journal of Training and Development, 39(1), 22–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-09-2013-0089

Schaffar, B. (2019). Svårigheter i att definiera begreppet kompetens [difficulties in defining the notion of competence]. Nordic Journal of Vocational Education And Training, 9(1), 111–128.

Schmidt, T. (2017). Context and capabilities: Tensions between managers’ and teachers’ views of advanced skills in VET. International Journal of Training Research, 15(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/14480220.2017.1331862

Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. Jossey-Bass.

Smith, B. C. (1996). On the origin of objects. The MIT Press.

Smith, E., & Yasukawa, K. (2017). What makes a good VET teacher? Views of Australian VET teachers and students. International Journal of Training Research, 15(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/14480220.2017.1355301

Southren, M. (2015). Working with a competency-based training package: A contextual investigation from the perspective of a group of TAFE teachers. International Journal of Training Research, 13(3), 194–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/14480220.2015.1077722

Stasz, C. (1997). Do employers need the skills they want? Evidence from technical work. Journal of Education and Work, 10(3), 205–223.

Stephens, G. (2015). Uncertified and teaching: Industry professionals in career and technical education classrooms. International Journal for Research in Vocational Education and Training, 2(2), 119–135. https://doi.org/10.13152/IJRVET.2.2.4

Stern, B. B. (2006). What does brand mean? Historical-analysis method and construct definition. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(2), 216–223.

Suddaby, R. (2010). Editor’s comments: Construct clarity in theories of management and organization. Academy of Management Review, 35(3), 346–357.

Sudirman, S. P., & MM. (2017). Efforts to improve teacher competence in developing a lesson plan through sustainable guidance in SMKN 1 Mamuju. Journal of Education and Practice, 8(5), 114–119

Sullivan, W. M. (2005). Work and integrity: the crisis and promises of professionalism in America (2nd ed.pp. 1–33). Jossey-Bass.

Summers, J. O. (2001). Guidelines for conducting research and publishing in marketing: From conceptualization through the review process. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 29(4), 405–415.

Sutarto, H. P., & Jaedun, M.P.D. (2018). Authentic assessment competence of building construction teachers in Indonesian vocational schools. Journal of Technical Education and Training, 10(1), 91–108

Tähtinen, J., & Havila, V. (2018). Conceptually confused, but on a field level? A method for conceptual analysis and its application. Marketing Theory, 19(4), 1–25.

Tambunan, H. (2014). Factors affecting teachers’ competence in the field of information technology. International Education Studies, 7(12), 70–75. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v7n12p70

Tarekegne, C., Wesselink, R., Biemans, H. J. A., & Mulder, M. (2017). Developing and validating a competence profile for development agents: An Ethiopian case study. Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 23(5), 427–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2017.1368400

Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., & Smart, P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management, 14(3), 207–222.

Tynjälä, P. (2013). Toward a 3-P model of workplace learning: A literature review. Vocations and Learning, 6(2), 11–36.

van Dam, K., Schipper, M., & Runhaar, P. (2010). Developing a competency-based framework for teachers’ entrepreneurial behaviour. Teaching & Teacher Education, 26(4), 965–971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.10.038

van Uden, J. M., Ritzen, H., & Pieters, J. M. (2013). I think I can engage my students. Teachers’ Perceptions of student engagement and their beliefs about being a teacher. Teaching and Teacher Education: An International Journal of Research and Studies, 32, 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.01.004

Vygotsky, L. S. (1987). Thinking and speech. In N. Rieber & A. Carton (Eds.), The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky (Vol. 1, pp. 39–285). Plenum.

White, R. W. (1959). Motivation reconsidered: The concept of competence. Psychological Review, 66, 297–333.

Winterton, J., Delamare-Le Deist, F., & Stringfellow, E. (2006). Typology of knowledge, skills and competences. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Wittgenstein, L. (1999). Blå boken och bruna boken: Förberedande studier till Filosofiska undersökningar. Thales.

Wu, M., Huang, C., Kao, Y., Lue, Y., & Chen, L. (2018). Developing a professional performance evaluation system for pre-service automobile repair vocational high school teachers in Taiwan. Sustainability, 10(10), 3537. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103537

Zlatanovic, T., Havnes, A., & Mausethagen, S. (2016). A research review of nurse teachers’ competencies. Vocations and Learning, 10(2), 201–233.

Online resources

Cambridge Dictionary | English Dictionary, T. (2019). Cambridge Dictionary | English Dictionary, Translations & Thesaurus. From https://dictionary.cambridge.org/. Accessed 15 January 2018

Collins Dictionary | Definition, Thesaurus and Translations. (2019). From https://www.collinsdictionary.com/. Accessed 15 January 2018

Dictionary by Merriam-Webster. (2019). America's most-trusted online dictionary. From https://www.merriam-webster.com/. Accessed 15 January 2018

Availability of Data and Material

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Funding

Open access. PhD project funding provided by Stockholm University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests