Abstract

This research evaluates the psychometric properties of the Romanian version of the Police Stress Questionnaire (PSQ), featuring operational and organizational stress scales for police officers. We conducted three studies to test the reliability and validity of this questionnaire. The first study (N = 744) aimed at adapting and validating the Romanian version on the specific population. Confirmatory factor analysis of our two-factor model, each with 20 items grouped in a second-order factor, showed the good value of the fit indices: χ²(738) = 1420.11, p < .001; CFI = 0.992; TLI = 0.992; RMSEA = 0.035 [90% CI 0.033, 0.038]; SRMR = 0.059. Subsequently, we tested measurement invariance, demonstrating that the Romanian version of this questionnaire measures workplace stress (including operational and organizational stress factors) independently of the work environment (police officers vs. correctional officers). The second study (N = 394) confirmed PSQ’s convergent validity through positive correlations with stress perception, burnout, mental health complaints, and psychological distress and its discriminant validity through negative correlations with job satisfaction and work engagement. The third study tested the longitudinal invariance of the stress questionnaire for police (N = 317). The findings suggest that the PSQ is a reliable and valid tool, highlighting its significant impact on the well-being of Romanian police officers by facilitating stress management interventions through baseline and ongoing stress assessment. Future research should longitudinally assess police stress, incorporating multi-source data and diverse units, as well as exploring the impact of socio-demographic aspects for broader insights.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Law enforcement has been renowned as one of the most stressful occupations worldwide, associated with high physical and primarily mental demands (Magnavita et al., 2018; Purba & Demou, 2019). Researchers have been conducting studies to develop a stressors list within the police system based on personal experiences, observations, or interviews with police officers (e.g., Baldwin et al., 2019). Factors that have been identified here include the complexity of work, shift work, a large number of contacts with a public that accuses various problems, courts, poor community support, exposure to potentially traumatic events (directly or indirectly), issues related to equipment or workforce, conflictive relationships at work, pressure from direct managers, damage to physical health, permanent unpredictability of professional situations they are exposed, too.

In light of all these researches, studies have shown specific symptoms - cognitive, emotional, and behavioural - associated with prolonged exposure to stress, which can vary from decreasing level of workplace satisfaction, professional involvement and commitment, negative attitudes towards service beneficiaries (e.g., indifference or aggressive behavioural responses), up to apathy, depression, professional burnout, increased consumption of substances (coffee, alcohol, drugs), work-family conflict (separation, divorce). However, in our country, unfortunately, this category has hardly been subject to consistent studies on stress to provide practical solutions to reduce stress levels experienced by employees. On the other hand, despite the increased number of studies on occupational stress and burnout among police officers worldwide, researchers frequently use measurement instruments developed for different professional groups that apply neither to the specifics of police tasks nor to the risks they undergo (including physical ones).

To conclude this reasoning and consider the topic’s importance at an international level, the present research aims to validate the Police Stress Questionnaire (PSQ), elaborated by McCreary and Thompson (2006), on the police population in Romania. The PSQ has two scales: operational and organizational stress (PSQ-Op and PSQ-Org).

Theoretical framework

Work-related stress is a physiological, emotional, cognitive, and behavioural response pattern that occurs when workers face work demands that do not correspond to their knowledge, skills, or abilities and challenge their ability to cope. This stress negatively influences workers’ well-being, performance, and productivity (Quick & Henderson, 2016).

To better understand the relationship between the specific characteristics of police work stress, in the present study, we referred to the Job Demands-Resources theory (JD-R; Bakker & Demerouti, 2017), which is widely used to explain work-related stress. The JD-R theory claims that job demands initiate health impairment or stress processes that exceed the employee’s resources to cope with these demands. Therefore, from the perspective of the JD-R theory, besides job characteristics, the organizational work environment can also be considered a new type of work demand. The operational range of police work includes but is not limited to, shift work, long working hours, and physical and mental health dangers. At the same time, the organizational environment refers to the various aspects of organizational life that contribute to stress, such as changes in criminal legislation, dealing with internal investigations, the pressure to volunteer free time, behaviors of the people in them, and interpersonal interactions at work. In addition, the associated social stress, such as the difficulty of finding friends outside work, not having time for friends and family, and the pressure of maintaining a superior image in public, plays a vital role in the professional stress of police officers (Kukić et al., 2022). Therefore, police work, which involves heavy workloads, work pressure acts, and danger as job demand, when chronically high, can drain police officers’ psychological and physiological resources over time, resulting in burnout. The sustained demands of police work pressure can wear down officers’ mental, emotional, and physical resources, reducing their capacity to cope with work tasks and professional demands. Such a working environment affects both the individual and the organization (Queirós et al., 2020), stress leading to work-family conflict (Griffin & Sun, 2018), non-adaptive coping strategies and workplace stress (Zulkafaly et al., 2017), burnout, and even suicide (Purba & Demou, 2019), as well as reduced job performance (Kelley et al., 2019), counterproductive work behaviors (Smoktunowicz et al., 2015), and inappropriate interactions with citizens, such as the use of excessive force (Mastracci & Adams, 2020). In addition to this, the results of the research literature (EBSCO database) about the published scientific papers on instruments used to measure burnout and stress among police officers, carried out by Queirós et al. (2020), reveal the fact that Romania does not appear with any study on this topic in the specialized literature. Therefore, the present research aims to validate the Police Stress Questionnaire (PSQ), developed by McCreary and Thompson (2006), with two scales: operational and organizational stress (PSQ-Op and PSQ-Org); in this way, filling in the gap in the specialized literature as regards Romanian research studies.

The Police Operational Stress (PSQ-Op) scale and the Police Organizational Stress (PSQ-Org) scale are two commonly used measures of police stressors, both of which are useful for elucidating individual variation in perceptions of police-specific stress (McCreary et al., 2017). The authors conceptualize the stress factors experienced by police officers as belonging both to the category of operational factors (i.e., stress factors associated with the performance of the task, such as documents or traumatic events) and organizational factors (i.e., stress factors related to the administrative aspects in which police officers work, such as lack of resources or inadequate equipment). The questionnaire is easy to apply and does not take much time to complete, while police officers must rate the intensity of each stressor. Numerous studies have shown good reliability and validity regardless of whether the authors administered in English or translated into spoken language by police officers (Fayyad et al., 2021; McCreary et al., 2017).

Building on this foundation, it is intriguing to compare how these stressors are experienced in related but distinct roles within the law enforcement and correctional fields. Operational police officers and correctional officers from penitentiaries exhibit many similarities: shift work, relationships with colleagues, pressure to give up free time, traumatic events, and exposure to common sources of occupational stress. However, these two professions differ significantly in terms of work tasks, the work environment, and the populations they interact with. Given these distinctions, we considered it crucial to measure the invariance of the stress questionnaire across these two professional categories (Study 1).

In the second study, to gather evidence for the convergent and discriminative validity of the instrument, we tested concepts related to the professional stress of police officers, such as: stress perception, burnout, mental health complaints, and psychological distress, respectively, work engagement and job satisfaction. Based on previous research, we selected the concepts mentioned above to validate the Romanian version of the PSQ. First, to establish convergent validity, according to the specialized literature, we considered it appropriate to measure stress perception. Perceived stress is an individual’s general feelings or thoughts about stress (Perera et al., 2017). The two sets of measuring police stressors (organizational and operational) are expected to be related to stress generally perceived; that is, a police officer who experiences job stress may also perceive other aspects of his life as more stressful, compared to a police officer experiencing less job stress.

Consequently, the relationship between stress and well-being factors (i.e., physical and psychological well-being) has received much attention over the years, with researchers indicating a consistent association between the two. Namely, the more stress people experience, the more their physical and mental health diminishes. Previous research has shown that, among police officers, stressor factors have been linked to physical health complaints (high rates of cardiovascular disease, substance abuse, burnout, and post-traumatic stress disorder) (Magnavita et al., 2018; Purba & Demou, 2019), and mental health complaints (anxiety, depression, behavioural/ emotional control, and general positive affect), on the one side, and emotional distress, on the other side. Stress-related problems are often used in various studies to operationalize employees’ well-being (Vîrgă et al., 2017). Thus, we expect the relationship between police-specific stress factors, on the one side, and emotional distress and mental health complaints, on the other side, to be positive.

Regarding burnout as a consequence of work-related stress experienced by police officers, Maslach and Leiter (2008) have defined burnout as a response to prolonged exposure to occupational stress, which negatively affects individuals, organizations, and healthcare service recipients. More recent studies showed that burnout represents a physical and psychological symptom caused by overwork, including emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and decreased personal achievement. Researchers have concluded that burnout usually occurs in people who establish direct relationships with the target group they work with, resulting from the interaction between individual personality and environmental conditions (Maslach & Leiter, 2008). Numerous studies have shown that the exhaustion rate of the police force has been higher than that of other professionals due to the organization, subculture, and unique work and life factors of the police (Purba & Demou, 2019). The high degree of association between organizational and operational stress factors of police officers and burnout is high.

Furthermore, we expect that someone experiencing increased stress at the workplace will report lower levels of job satisfaction and work engagement, providing evidence for good discriminative validity of the questionnaire. Job satisfaction reflects a positive feeling towards the task performed. Through this value of job satisfaction, an individual will feel confident and enthusiastic in every job undertaken (Vîrgă, 2015). Studies on the relationship between occupational stress and job satisfaction have shown that occupational stress work and job satisfaction are interconnected because a high level of occupational stress is associated with low job satisfaction values. The type of stress that affects job satisfaction experienced by police officers stems from the satisfaction of psychological and physiological needs. Perceived levels of stress have a profound negative effect on both police workers’ job satisfaction and their quality of life (Alexopoulos et al., 2014). Work engagement is an attitudinal and motivational state related to work, defined by vigour, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli et al., 2002). Thus, work engagement is manifested by higher positive affect, dedication, and greater concentration in work. Workplace stressors negatively affect energy and mental resilience during work (vigor), feelings of meaningfulness, enthusiasm, and pride in work (dedication), complete and deep concentration at the workplace, and difficulty detaching from work (absorption), which can have a negative effect on worker engagement.

Based on the evidence above, the following hypotheses were formulated:

-

H1: Police stress is positively related to perceived stress.

-

H2: Police stress is positively related to (a) burnout, (b) psychological distress, and (c) mental health complaints.

-

H3: Police stress is negatively related to (a) job satisfaction and (b) work engagement.

The present study

The objectives of the first study were the correct translation and linguistic adaptation of the items of two scales of the PSQ questionnaire, analysis of the structure of the questionnaire, and the internal consistency indices for the specific population of police officers in Romania, respectively testing the invariance of the proposed instrument on two samples of police officers from different working environments (operational police officers and correctional officers from penitentiaries). In the second study, we tested the cross-validation of the previous model and analyzed the relationship between police stress and other variables (perceived stress, burnout, psychological distress, mental health complaints, work engagement, and job satisfaction), thereby providing evidence regarding the relative criterion validity of the scale. For the third study, the objectives were to test the invariance over time of the scale and its fidelity through the test-retest method, thus showing the robustness of the Romanian version of the PSQ.

Study 1: adapting and validating the Romanian version of the PSQ

Our main objective for this first study was the correct translation and linguistic adaptation of the items of the two scales of the questionnaire (PSQ-Op and PSQ-Org, each with 20 items), analyze the structure of the questionnaire and the indices of internal consistency for the specific population of police officers in Romania, respectively testing the invariance of the proposed instrument on two samples of police officers from different work environments (operational police officers and correctional officers from penitentiaries).

Method

Scales translation

The translation processes followed the well-known principles of the back-translation procedure (Brislin, 1970). Two independent researchers translated the original English version of the PSQ (McCreary & Thompson, 2006) into Romanian. After that, this version was translated back into English. Finally, for the conceptual content to be correct and appropriate, the questionnaire was analyzed by two bilingual psychologists who evaluated the quality of the content and the proposed measured concept from the perspective of their accuracy and relevance. For a better understanding and suitability to the specifics of the population, in the process of translation, some items were slightly adapted to suit the Romanian specifics best. For example, “Bureaucratic red tape” was translated as “Excessive routine procedures that lead to delays (e.g., excessive bureaucracy)”.

Participants and procedure

This study’s convenience sample consisted of 744 police officers (operational police officers and correctional officers from penitentiaries) aged 18 and 59 (M = 35.52, SD = 9.19); 91.7% were men. Four hundred and forty-two (59.8%) have completed higher education (university and postgraduate), and about half of the sample are married (54.7%). The work experience of the participants included in the study ranged between 2 months and 38 years, with an average of 13.2 years (SD = 9.1). The research received a favorable ethical opinion from the Scientific Council of University Research and Creation at our university (number 77790 of 23.11. 2022), and we obtained the necessary approvals to carry out the research in this professional category.

We chose a convenience sample in compliance with the criteria for homogeneous convenience sampling because the target population (not just the sample studied) is a specific sociodemographic subgroup. As an inclusion criterion in the study, we chose the specificity of the activity (operative police officers) randomly represented in terms of age, gender, or length of service. Thus, considering the homogeneous population in relation to the announced criteria, the sample can be representative of the entire population even if it is a convenience sample and provide accurate population estimates (for a circumscribed population). The data were collected by applying the questionnaires by the organization’s psychologist during the police officers’ working hours, the research representing a study within a doctoral project. The purpose of the research was presented on the first page of the questionnaire; as part of the informed consent, all participants expressed their agreement regarding participation in the study. Police officers completed the questionnaires voluntarily, received no incentives, and were also guaranteed confidentiality and anonymity for this research. The questionnaires were anonymous, and the data were kept in a database with restricted access, available only to research team members.

Measures

This study used the translated version of the PSQ (McCreary & Thompson, 2006). The instrument has 40 items and two scales, each with 20 items assessing operational (PSQ-Op) and organizational (PSQ-Org) police stress factors. The items answer the question, “How much stress did certain situations cause you in the last 6 months?”, an example of an item for operational stress factors is: “Lack of understanding from family and friends about your work”. For organizational stress factors, an example item is: “Inadequate equipment”. Responses were given on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (no stress at all) to 7 (a lot of stress).

Data analysis

To explore the measurement model of the PSQ scale on the Romanian population, we made a CFA on the 40–item scale using the R software, specific for the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012). We used a couple of criteria and fit indices to evaluate the goodness of fit registered by the model: three absolute fit indices (Chi-square test, Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation – RMSEA, and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual – SRMR) and two relative fit indices (Tucker Lewis Index – TLI; and Comparative Fit Index – CFI). The optimal thresholds used were a value of 0.08 or under for SRMR and RMSEA; for CFI and TLI, equal and over 0.90 (Marsh et al., 2005).

We also used the “WLSM” estimator (weighted least squares mean adjusted), given its proven superiority in handling ordinal data, particularly suitable for responses equal to or lesser than a 7-point Likert-type scale (Schmitt, 2011). This preference is underscored by findings from Yu and Muthen (2002), which highlight WLSM’s enhanced performance for sample sizes exceeding 500 participants. The ordinal nature of our measures further justifies our choice. Also, WLSM employs a polychromic covariance matrix and probit regression coefficient, treating scale items as ordinal data (DiStefano & Morgan, 2014), thus providing a more accurate estimation approach compared to other estimators like maximum likelihood and its variants (Brauer et al., 2023). These traditional estimators often underestimate factor loadings and fail to optimally estimate the χ² test of fit for ordinal responses (Tarka, 2017). Therefore, we evaluated three measurement models: a single-factor model (M1; Podsakoff et al., 2012) to test for common method variance, a two-factor model (M2) based on the initial proposal by McCreary and Thompson (2006), and a second-order model (M3). We chose to test the second-order model as well since, according to Flora (2020), this type of model allows for obtaining total scores (as a score for the higher-order construct, in our case, work stress) as well as subscale scores (as a score for the lower-order constructs, such as operational stress and organizational stress). We also used McDonald’s omega to test the scale’s reliability, whose value must be greater than 0.70 (Viladrich et al., 2017).

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and internal consistency values of the PSQ. The mean of the scale was 70 (SD = 22.95 for PSQ-Op and SD = 25.5 for PSQ-Org). The mean of the questionnaire is 140 (SD = 46.5). The item-total correlation values varied between r = .51 and r = .82, p < .01 for PSQ-Op, respectively r = .55 and r = .82, p < .01 for PSQ-Org. The McDonald’s omega for the PSQ-Op was 0.94, 0.95 for the PSQ-Org, and 0.97 for PSQ. As Table 1 illustrates, we can further consider the instrument well adapted to the tested population with descriptive statistics and internal consistency values.

Confirmatory factor analysis

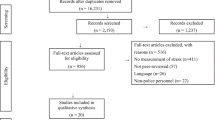

One factor model fit the data register a CFA of χ2 (740) = 5086.12, p < .001, CFI = 0.984; TLI = 0.983; RMSEA = 0.051; 90% CI [0.050, 0.052], SRMR = 0.065. Next, the two-factor model made in the first study indicates a good fit with CFA values of χ2 (739) = 4357.15, p < .001; CFI = 0.986; TLI = 0.986; RMSEA = 0.046; 90% CI [0.045, 0.048], SRMR = 0.059. Moreover, the third model, the two-factor model converging into a single factor, had the best indices among the three tested models, respectively χ2 (738) = 1420.11, p < .001; CFI = 0.992; TLI = 0.992; RMSEA = 0.035; 90% CI [0.033, 0.038]; SRMR = 0.059. Figure 1 shows that the standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.46 to 0.82, p < .001 for all items.

Measurement invariance across the work environment

The results of the invariance analysis (Table 2) assert that configural invariance across the work environment was established, χ2 (1479) = 5240.288, p < .001; CFI = 0.986; RMSEA = 0.048; 90% CI [0.046, 0.049]; SRMR = 0.062. Thus, the factorial structure of the scale was maintained regarding the work environment of the participants (police and correctional officers), which allowed us to move on to the comparison of subsequent models. Further, factor loading was constrained, and all criteria indicated that data also supported metric invariance (ΔCFI = 0.014). Last, we imposed equality indices, and the data did not show a difference in model fit (ΔCFI = 0.003), which offered arguments for scalar invariance. Ultimately, the indicators of invariance illustrated no difference across police work environments.

The confirmatory factor analysis supported the two-factor structure converging into a single factor as the most appropriate for the population of police officers in Romania. Consequently, the adapted PSQ scale on the Romanian population is adequate, demonstrating the preservation of the initial factorial structure and internal consistency. Our result replicates the scale design obtained by the scale’s authors and agrees with their recommendation to include in the factor analysis a higher-order model with a single factor (McCreary & Thompson, 2006). The instrument showed no significant differences across police work environments as configural, metric, and scalar invariance. Hence, the PSQ has good psychometric proprieties and can be used in testing Romanian samples, furthering the next steps of our research.

Study 2: cross-validation of the Romanian version of the PSQ and validity estimates

Based on the previous Study 1, we noticed that the Romanian version of the PSQ had good internal consistency and construct validity. Thus, in this study, we tested the cross-validation of the previous model using another sample and provided evidence for the scale’s construct validity. Therefore, we proposed to re-analyze the structure of the stress questionnaire for the specific population of Romanian operative police officers to demonstrate this instrument’s concurrent and discriminative validity.

Method

Participants and procedure

In this study, we shared the initial sample and used only police officers from operational structures. We selected a convenience sample of 394 participants through a non-probabilistic method of sampling. Starting from the principle of cross-validation, we chose to omit part of the data to check if the initially built model is confirmed on different subsets of data in order to be able to predict the robustness of the scale. For this population, the age was between 19 and 59 (M = 35.6, SD = 9.5), 87.4% were men, 88.7% were agents, and 11.3% were officers, respectively 80.1% were operational police officers. Two hundred sixty-seven (68.6%) had an academic degree, and approximately half of the sample was married (53.7%). Regarding work experience, the participants included in the study had experience between 2 months and 35 years, with an average work experience of 13.8 years (SD = 9.2). Police officers participated in this study voluntarily, were not rewarded in any way, and all participants consented to participate in the research, being guaranteed anonymity and confidentiality.

Measures

Participants completed the Romanian version of PSQ. The McDonald’s omega value was 0.93 for the PSQ-Op subscale, 0.94 for the PSQ-Org subscale, and 0.96 for the PSQ. Comparing these coefficients with those from the original PSQ and other adaptations, we observed, in the original study of McCreary and Thompson (2006), that Cronbach’s alphas had the same good values for the PSQ-Op was 0.93, and the alpha for the PSQ-Org was 0.92. Also, Cronbach’s alpha recorded the value of 0.96 for PSQ-Op and 0.95 for the PSQ-Org for de Serbian version of PSQ (Kukić et al., 2022). For the Police Stress Questionnaire, adapted to the German population (PSQ-G; Willemin-Petignat et al., 2023), Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95 and Donald’s ω = 0.95; for the PSQ-Op subscale Cronbach’s alpha was 0.93 and ω = 0.93; for PSQ-Org subscale Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91 and ω = 0.91. We can, therefore, observe that the instrument has a good internal consistency both for the Romanian population and for other populations where it was adapted, demonstrating the good reliability of the instrument.

Stress perception was measured with the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Perera et al., 2017). The 10-item PSS scale measures global perceived stress across the past 30 days on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never, to 4 = very often). Six of the ten items were worded and scored in the non-reversed direction (e.g., “How often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life?”), and four were worded and scored in the reversed direction (e.g., “How often have you felt that things were going your way.”). Total scores range from 0 to 40. For this scale, McDonald’s omega had a value of 0.66.

Burnout was evaluated using the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (Schaufeli et al., 1996). Two scales were used to evaluate core-burnout: emotional exhaustion (5 items; “I feel emotionally drained from my work.”) and cynicism (4 items; “I have become less enthusiastic about my work.”). All items were scored on a 7-point Likert-type scale, from 0 (never) to 6 (always). McDonald’s omega value was 0.90 for this scale.

Psychological distress was evaluated with the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10; Kessler et al., 2002). The scale consists of 10 items that investigate signs of psychological distress, such as depressive and anxious symptoms, in the last 30 days, using a 5-point Likert scale as a response model, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Usually, the K10 is assessed with a total score, and the sum of the scores indicates the stress level, where high scores correspond to high stress levels. An example of an item is: “In the past four weeks, about how often did you feel so nervous that nothing could calm you down?”. The value of McDonald’s omega coefficient was 0.87 for this questionnaire.

Mental health complaints were evaluated using a 5-item scale developed by Berwick et al. (1991) and previously adapted in Romanian (Vîrgă et al., 2017). A sample item is “How much of the time during the last month have you felt calm and peaceful?” Response categories varied from 1 (never) to 6 (always) on a Likert-type scale. McDonald’s omega value on the mental health complaints scale was 0.81.

Work engagement was evaluated using the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (Schaufeli et al., 2002), adapted from the Romanian population (Vîrgă et al., 2009). The questionnaire has nine items, divided into three subscales: vigor (“At my job, I feel strong and vigorous.”), dedication (“My job inspires me.”), and absorption (“I forget myself when I am working.”), also calculating a global score. The assessment was made on a 7-point scale − 0 (never) and 6 (daily). McDonald’s omega value was 0.86 for this scale.

Job satisfaction was assessed using a specific scale from the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire (Cammann et al., 1979), which was previously adapted in Romania (Vîrgă, 2015). The scale has three items with a response on a 7-point scale (1 = total disagreement, 7 = total agreement). A sample item reads: “In general, I like working here.”. McDonald’s omega value on the job satisfaction scale was 0.90.

Data analysis

In this second sample, we made another CFA on the PSQ using R software, specifically the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012). For CFA, we proceeded in the same way as in the first study: the “WLSM” estimator for the analysis and the cut-off values for the fit indices that indicate the goodness of fit for the model are 0.08 and under for SRMR and RMSEA of 0.90 and over for CFI, TLI (Marsh et al., 2005). Further on, we conducted the Pearson correlations (SPSS Statistics for Windows, v 25) between PSQ and stress perception, burnout, mental health complaints, psychological distress, job satisfaction, and work engagement. The concurrent and discriminant validity of the instrument was tested by analyzing its correlations with the other questionnaires used.

Results

The results of CFA conducted on the second sample (N = 394) indicated a good fit of the second-order factor model, replicating the findings of our first study in the second sample: χ2 (738) = 830.920, p < .001, CFI = 0.998; TLI = 0.998; RMSEA = 0.018; 90% CI [0.010, 0.024]; SRMR = 0.058. Further, the correlation matrix results showed a relationship between the PSQ scales and the other measured constructs (stress perception, burnout, mental health complaints, psychological distress, job satisfaction, and work engagement). The police officers stress, both as a total score and each scale separately, registered positive relationships with stress perception (r = .49, p < .01) - PSQ, r = .48, p < .01 - PSQ-Op, r = .46, p < .01 - PSQ-Org), burnout (r = .59, p < .01 - PSQ, r = .57, p < .01 - PSQ-Op, r = .56, p < .01 - PSQ-Org), mental health complaints (r = .42, p < .01 - PSQ, r = .38, p < .01 - PSQ-Op, r = .42, p < .01 - PSQ-Org), and psychological distress (r = .46, p < .01 - PSQ, r = .44, p < .01 - PSQ-Op, r = .44, p < .01 - PSQ-Org). Also, police stress correlated negatively with job satisfaction (r = − .21, p < .01 - PSQ, r = − .18, p < .01 - PSQ-Op, r = − .22, p < .01 - PSQ-Org), and work engagement (r = − .36, p < .01 - PSQ, r = − .35, p < .01 - PSQ-Op, r = − .35, p < .01 - PSQ-Org). Thus, the results confirm our hypothesis that the PSQ has good concurrent validity. Our results support the first hypothesis because police stress positively correlates with perceived stress. Subsequently, police stress is positively correlated with (a) burnout, (b) psychological distress, and (c) mental health complaints; these results confirm the second hypothesis. Finally, police stress is negatively correlated with (a) job satisfaction and (b) work engagement, and these results support the third hypothesis formulated. Thus, police officers who face job-related stress record increased levels of professional burnout, psychological distress experienced, and complaints related to mental health. Also, the negative relationships of the PSQ with job satisfaction and work engagement provide arguments for the discriminant validity of the PSQ scale (Table 3).

Study 3: testing longitudinal invariance and psychometric properties

Our goal for this study was to test the robustness of the Romanian version of the PSQ by testing the scale’s invariance over time and its reliability by the test-retest method.

Method

Participants and procedure

For this study, we recruited a convenience sample of 317 correctional officers from penitentiaries aged between 18 and 55 (M = 34.3, SD = 8.4). Among these, 96.8% were men, with work experience varying between 6 months and 32 years, with an average of 11.5 years (SD = 8.4) for this category. Regarding the level of education, 161 correctional officers (50.8%) declared themselves graduates of higher education (university and postgraduate), and 53.9% are married.

This was a two-wave study, with the PSQ instrument being administered at two different time intervals over one year. All correctional officers from penitentiaries who completed the questionnaire in Wave 1 also participated in the research in Wave 2.

Measures

After one year, we assessed work stress using the Romanian version of the PSQ, both scales: PSQ-Op (20 items) and PSQ-Org (20 items) at T1 and T2.

Data analysis

In the third study, we tested the scale’s stability over time by conducting a longitudinal measurement invariance assessed at different application times within a consistent group. To explore the model, we used the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012) in R software. As with measurement invariance across work environments, measurement invariance over time is built by testing: Configural Invariance (M1) – a model with the same number of factors and, therefore, the structure of the instrument prevails across all groups even at different times of application; Metric Invariance (M2) – a model where we can observe no discrepancies of the factorial loadings, across the applications; Scalar Invariance (M3) – a model where we cannot find any invariance of items intercept across different times of application (Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). Consequently, we analyzed the configural, metric, and scalar invariance at two different time intervals over one year to see if the covariance in the two groups could be fitted in the same factor model. We applied the same fit indices mentioned above (RMSEA, CFI, SRMR, and TLI), and we had a good fit if obtained values were ≤ 0.08 for RMSEA; SRMR ≤ 0.08; CFI and TLI ≥ 0.90 (Marsh et al., 2005).

Results

Results of the longitudinal invariance analysis (Table 4) show that the instrument demonstrates configural invariance across time χ2 (1479) = 5072.000, p < .001; CFI = 0.988; RMSEA = 0.045; 90% CI [0.043, 0.046]; SRMR = 0.065. These results suggest that the factor structure was well-kept across two intervals, providing a baseline model. As we increased the model constraints at each step of the way, equality constraints were imposed, and the factorial structure of the scale was maintained. Thus, the data supported metric invariance (ΔCFI = 0.000). Then, the intercepts were constrained to be equal for both groups in different time intervals to test the scalar model. Results indicated no invariance in model fit (ΔCFI = 0.001). As a result, the factor structure of the Romanian version of the PSQ scale is stable over time.

Also, we evaluated the reliability of the Romanian version of the PSQ scale in the third study using the test-retest method. We measured the consistency across time through the McDonald’s omega coefficient and test-retest correlation for both subscales in two different moments of application. In the first wave of application, McDonald’s omega was 0.95. For the organizational stress, the McDonald’s omega value was 0.96. For the entire questionnaire, McDonald’s omega was 0.97. In the second wave, the McDonald’s omega had a value of 0.96 for the PSQ-Op and 0.96 for PSQ-Org. For the entire questionnaire, 0.97 was the value of this coefficient. We tested the consistency across time with the test-retest method to ensure fidelity to the Romanian version of the PSQ scale. We tested the correlation for both subscales at two different application times for the test-retest reliability. Thus, PSQ-Op registered positive and significant relationships from the first wave of applications to the second (r = .23, p < .01), such as PSQ-Org (r = .26, p < .01) and PSQ (r = .27, p < .01). Therefore, we can say that the results related to the Romanian version of the PSQ scale indicate that this scale is a reliable instrument with good psychometric characteristics. Study 3 confirms that the Romanian version of the PSQ scale has good reliability (internal consistency and test-retest correlations) and stability in time (by measurement invariance across time). These results showed that the Romanian version of the PSQ scale is valid and can be applied in the context of the police organizational environment in Romania.

General discussions

This study aimed to adapt and validate the Romanian version of the PSQ on the specific population of police officers in Romania. We conducted three studies to assess the psychometric properties of the scale. The confirmatory factor analysis showed that the model with two factors, grouped into a second order factor, has a good value of fit indices; our results confirm the structure initially proposed by the authors, agreeing with their recommendation to include in the analysis factorial a higher-order, single-factor model (McCreary & Thompson, 2006). Related to theoretical implications, this study shows similar results to Willemin-Petignat et al. (2023) for validating the Police Stress Questionnaire (PSQ) in Germany adapted version, with one-factor structure as in the original English version questionnaire, sustains the same construct validity as in the questionnaire developed by McCreary and Thompson (2006). Other research until now that validated the police stress questionnaire modified its factorial structure (for example, Queirós et al., 2020; Sagar et al., 2014) or reduced the number of items (i.e., Irniza et al., 2014; Sagar et al., 2014).

In line with the JD-R theory, in police work, job demands are related to operational (such as work schedules, shift work, long work hours, overtime, or work-family conflict) and organizational stressors (such as lack of resources, lack of a support system provided by supervisors and/or colleagues) (Violanti et al., 2017). In agreement with other studies carried out in this field, our results show that these operational and organizational stress factors, which may be a greater source of stress for police officers as they represent daily routines, were associated with burnout, psychological distress, mental health complaints, and can determine poor physical health, poor mental health, and physician-diagnosed morbidity (Finney et al., 2013; Goh et al., 2015). The instrument did not show significant differences according to the work environment of police officers as measurement invariance, demonstrating that the Romanian version of this scale measures the same levels of stress at work for police officers, regardless of the work environment (police officers vs. correctional officers from penitentiaries). Therefore, the PSQ has good psychometric properties and can be used to test stress levels of the specific population of Romanian police officers.

The objective of the second study was to cross-validate the second-order factor model and examine the relative validity of the criterion of the PSQ adapted to the Romanian police population. The results replicated the first study’s results, demonstrating the second-order structure, with the two scales, PSQ-Op and PSQ-Org (each with 20 items), grouped into a single factor of occupational stress. We also investigated the relationship between police stress and other constructs (stress perception, burnout, psychological distress, mental health complaints, work engagement, and job satisfaction). The results showed that police officers’ occupational stress has a positive relationship with burnout, mental health complaints, psychological distress, as well as the perception of stress. In other words, police officers who experience increased levels of occupational stress report more mental health complaints, increased psychological distress, and high burnout levels, perceiving various aspects of their professional or personal life as more stressful, in contrast to police officers who report lower levels of occupational stress (Purba & Demou, 2019).

Furthermore, our results have revealed a negative association between police stress and job satisfaction and work engagement. Thus, in agreement with the previous literature, police officers with an increased level of operational or organizational stress are less satisfied with their work and less involved in carrying out their professional tasks, thus affecting their level of professional performance. Therefore, the conditions for proving criterion-related validity and specific convergent validity were met. The discriminative validity has also been demonstrated.

The third study showed that the instrument maintains its psychometric values over time. Thus, the results confirmed that the Romanian version of the PSQ has good reliability (internal consistency and test-retest correlations) and stability over time (through the measurement’s invariance over time). These results confirm that the Romanian version of the PSQ is valid and can be applied in the police organizational environment in Eastern European countries.

Practical implications

Although occupational stress is an intensively studied topic, when dealing with it among the police or its level of study in Romania, things are different. First, a potential limitation for many studies is that they only assess general stressors and fail to incorporate those unique to specific, higher-stress occupations. This limits the possibility of generalizing the results to those occupations with an increased stress level, and researchers have begun to question whether these instruments measuring general occupational stress have the same or similar psychometric properties across different occupational groups (Lyne et al., 2010). Therefore, studying stressors unique to specific occupations, especially those highly stressful ones, becomes essential. Thus, our results can contribute to scientific research on police forces, a topic that has received globally increased attention, with a particular focus on the causes of stress and burnout. This study provides solid evidence for using a valid and reliable occupational and organizational stress questionnaire for police officers, adapted to the specifics of work and the unique stressors they face at the workplace, in the context of the lack of such instruments for the specific population in Romania.

On the other hand, decision-makers within police organizations can use this questionnaire to determine baseline levels and monitor stress within their units. This can be done in at least two equally useful ways with important practical contributions: for example, by introducing this questionnaire into the periodical psychological evaluations of police officers, annual monitoring of the felt level of work stress of the workers could be achieved. On the other hand, when the organizational diagnosis of a unit or subunit is occasionally carried out, and there is a suspicion of a problem related to an increased stress level of the police officers in the respective collective, the tool can be used successfully to diagnose this problem. Moreover, the two separate scales, which can be used independently or together, depending on the identified problem, make the intervention much more practical and targeted.

Such information provides a valuable basis for designing a less stressful work environment for employees. It is also essential in developing organizational intervention programs for stress management and increasing police resilience. In order to improve workers’ occupational health, it is crucial to identify the occupational stress level, especially since we are dealing with a professional category that faces increased stress levels and specific factors determined by the nature of their work. Stress prevention and specific interventions are much easier to implement when we have short, specific, and validated instruments on the reference population. For instance, if following the use of the questionnaire, either for the periodical evaluation or for the diagnosis, a problem related to the increased level of professional stress is identified within a group, an intervention program can be designed in order to reduce it, either taking into account only organizational or operational stress factors, or both categories, depending on the results provided by the tool. For preventive activities, we may be better informed and, thus, more precise and efficient if we are aware of the inherent risk of police stress in a multi-dimensional quantitative, qualitative, and contextual sense.

Limitations and directions for future research

Even if the results obtained are encouraging, this study has some limitations to consider when interpreting results. The first limitation of this research is that all variables were measured using self-reported instruments, so the common method variance may be a potential risk, but the confirmatory factor analysis showed that the single factor model (M1; Podsakoff et al., 2012) did not fit the data well. Therefore, with the PSQ-Op and PSQ-Org as valid and reliable instruments, further research should investigate the occupational stress of police officers in longitudinal studies to establish its antecedents and consequences at work and, last but not least, to use data from multiple sources (e.g., objective measurements related to pulse, heart rate, cortisol level, etc.) to rule out the possibility of common method bias. Considering that numerous studies have shown associations of occupational stress with metabolic syndromes, cardiovascular diseases, neurological disorders, depression, or absenteeism (Fekedulegn et al., 2013; Violanti et al., 2017), further studies could consider studying how increased levels of occupational stress will be associated with its objective measures (in the sense of the previously mentioned) for a sample of different police units in the next three months for example, thus providing conclusive evidence of the predictive validity of the instrument.

In this study, we clearly explained the research’s purpose, ensuring respondents understood that this was not an evaluation and that all questionnaires were anonymous and confidential. This approach aimed to minimize common method variance as much as possible. The questionnaires were administered by a psychologist who encouraged police officers to ask questions about any unclear items. We strived to make items specific, simple, and concise, avoiding double-barreled questions and complex syntax. However, we cannot completely eliminate the impact of common method variance with these procedural remedies alone. Future research should consider collecting data from multiple sources, such as indirect measures, or employing statistical methods to control for the effects of common method variance on the findings. A second limitation refers to testing PSQ only in specific cultural Romanian contexts. To extend the degree of generalization of the results at the cross-culture level, future studies could consider comparing the effect of such stress factors on police officers working in different countries. Thus, the general stress level may be perceived to be different depending on the cultural factors.

Moreover, this study focused on the psychometric properties of the scale. The analyses are not aimed at establishing reference thresholds (cut-off values for low, moderate, and high stress) useful in identifying police officers’ stress levels. Further research may also consider the impact of individual and professional characteristics such as age, gender, or career position on stress, given that the meta-analysis by Aguayo et al. (2017) showed that socio-demographic factors could also be associated with police burnout. Therefore, experienced employees, who typically are older and have longer tenure, may have developed more effective strategies to manage stress and protect themselves, such as employing advanced coping mechanisms compared to their younger counterparts. According to the JD-R theory, this could lead to an increase in their personal resources (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). On the other hand, daily confrontations with stress factors may lead to higher levels of exhaustion and physical health issues, particularly among police officers with greater seniority. This combination—less effective stress management strategies and long-term exposure to stress due to seniority—is crucial to study in order to design effective prevention or intervention programs. Additionally, future studies should explore how operational or organizational stressors affect female and male police officers differently, particularly in terms of the overall stress levels experienced.

Another limit of the present study may be related to the sincerity of the police officers’ answers, both in matters related to sensitive factors (e.g., confrontation with superiors, favoritism, etc.) and in terms of their general level of stress felt. Even if the police officers were assured of the anonymity and confidentiality of their answers, it is possible that under-reporting or over-reporting might have occurred (for example, in some cases, they may believe that by reporting increased levels of occupational stress, they may face discrimination or be referred for psychological evaluation). A larger sample size and more representative of all Romanian police officers will increase the precision of the data collected.

Conclusions

This study provided consistent evidence regarding the reliability and validity of the Romanian version of the PSQ. This instrument provides insight into the organizational and occupational stress of police officers. On the other hand, this research draws attention to the importance of occupational health services in risk prevention and recovery for workers who play a crucial role in society, such as police officers who deal with national safety and security. Studies that seek to identify police officers’ stress levels will need to continue and contribute to the evaluation of both risk and protective factors that influence police officers, their well-being, quality of life, job performance, and mental health, as well as their families and the beneficiaries of police services (society and citizens). Regular assessments through the PSQ would provide a human-centered approach to the organization of the work environment and a consistent evaluation of the subjective perceptions of stress for each police officer. Thus, an increased level of stress resulting from the periodic evaluation with the PSQ allows the psychologist of the organization to make objective recommendations regarding the respective police officer, for example, regarding the provision of assistance services or psychological counseling through which effective coping strategies or efficient relaxation methods can be taught, or even changing the line of work if the effects are significant on the worker’s physical health or psychological well-being. More than that, the existence of the two scales separately allows for more precise identification of the nature of the stressors so that the measures are as appropriate and suited to the police officer and the problem he has. In this way, the interventions would be much more beneficial both for the workers and for the organization, the human-centered approach facilitating the increase in the level of satisfaction and involvement of the police officers, and these benefits bring increased performance to the institution and decrease the probability of involvement in adverse events. In conclusion, the three studies show that the stress related to the police officers’ workplace can be measured with the Romanian version of the PSQ.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Aguayo, R., Vargas, C., Cañadas, G. R., & De la Fuente, E. I. (2017). Are socio-demographic factors associated to burnout syndrome in police officers? A correlational meta-analysis. Anales De Psicología/Annals of Psychology, 33(2), 383–392. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.33.2.260391

Alexopoulos, E. C., Palatsidi, V., Tigani, X., & Darviri, C. (2014). Exploring stress levels, job satisfaction, and quality of life in a sample of police officers in Greece. Safety and Health at Work, 5(4), 210–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2014.07.004

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22, 3. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056

Baldwin, S., Bennell, C., Andersen, J. P., Semple, T., & Jenkins, B. (2019). Stress-activity mapping: Physiological responses during general duty police encounters. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2216. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02216

Berwick, D. M., Murphy, J. M., Goldman, P. A., WareJr., J. E., Barsky, A. J., & Weinstein, M. C. (1991). Performance of a five-item mental health screening test. Medical Care, 29, 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199102000-00008

Brauer, K., Ranger, J., & Ziegler, M. (2023). Confirmatory factor analyses in psychological test adaptation and development. A nontechnical discussion of the WLSMV estimator. Psychological Test Adaptation and Development, 4(1), 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1027/2698-1866/a000034

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301

Cammann, C., Fichman, M., Jenkins, D., & Klesh, J. (1979). The Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire (pp. 71–138). University of Michigan.

DiStefano, C., & Morgan, G. B. (2014). A comparison of diagonal weighted least squares robust estimation techniques for ordinal data. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(3), 425–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.915373

Fayyad, F. A., Kukić, F. V., Ćopić, N., Koropanovski, N., & Dopsaj, M. (2021). Factorial analysis of stress factors among the sample of Lebanese police officers. Policing: An International Journal, 44(2), 332–342. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-05-2020-0081

Fekedulegn, D., Burchfiel, C. M., Hartley, T. A., Andrew, M. E., Charles, L. E., Tinney-Zara, C. A., & Violanti, J. M. (2013). Shiftwork and sickness absence among police officers: The BCOPS study. Chronobiology International, 30(7), 930–941. https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2013.790043

Finney, C., Stergiopoulos, E., Hensel, J., Bonato, S., & Dewa, C. S. (2013). Organizational stressors associated with job stress and burnout in correctional officers: A systematic review. Bmc Public Health, 13, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-82

Flora, D. B. (2020). Your coefficient alpha is probably wrong, but which coefficient omega is right? A tutorial on using R to obtain better reliability estimates. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 3(4), 484–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245920951747

Goh, J., Pfeffer, J., & Zenios, S. A. (2015). Workplace stressors & health outcomes: Health policy for the workplace. Behavioral Science & Policy, 1(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1353/bsp.2015.0001

Griffin, J. D., & Sun, I. Y. (2018). Do work-family conflict and resiliency mediate police stress and burnout: A study of state police officers. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 43, 354–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-017-9401-y

Irniza, R., Emilia, Z. A., Saliluddin, S. M., & Isha, A. S. N. (2014). A psychometric properties of the malay-version police stress questionnaire. The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences: MJMS, 21(4), 42–50.

Kelley, D. C., Siegel, E., & Wormwood, J. B. (2019). Understanding police performance under stress: Insights from the biopsychosocial model of challenge and threat. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 457515. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01800

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L., … Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291702006074

Kukić, F., Streetman, A., Koropanovski, N., Ćopić, N., Fayyad, F., Gurevich, K., & Heinrich, K. M. (2022). Operational stress of police officers: A cross-sectional study in three countries with centralized, hierarchical organization. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 16(1), 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paab065

Lyne, K. D., Barrett, P. T., Williams, C., & Coaley, K. (2010). A psychometric evaluation of the occupational stress indicator. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73, 195–220. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317900166985

Magnavita, N., Capitanelli, I., Garbarino, S., & Pira, E. (2018). Work-related stress as a cardiovascular risk factor in police officers: A systematic review of evidence. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 91, 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-018-1290-y

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T., & Grayson, D. (2005). Goodness of Fit in structural equation models. In Contemporary psychometrics (pp. 275–340). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2008). Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(3), 498–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.498

Mastracci, S. H., & Adams, I. T. (2020). It’s not depersonalization, It’s emotional labor: Examining surface acting and use-of-force with evidence from the US. International Journal of Law Crime and Justice, 61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2019.100358

McCreary, D. R., & Thompson, M. M. (2006). Development of two reliable and valid measures of stressors in policing: The operational and organizational police stress questionnaires. International Journal of Stress Management, 13, 494–518. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.13.4.494

McCreary, D. R., Fong, I., & Groll, D. L. (2017). Measuring policing stress meaningfully: Establishing norms and cut-off values for the operational and organizational police stress questionnaires. Police Practice and Research, 18(6), 612–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2017.1363965

Perera, M. J., Brintz, C. E., Birnbaum-Weitzman, O., Penedo, F. J., Gallo, L. C., Gonzalez, P., Gouskova, N., Isasi, C. R., Navas-Nacher, E. L., Perreira, K. M., Roesch, S. C., Schneiderman, N., & Llabre, M. M. (2017). Factor structure of the perceived stress Scale-10 (PSS) across English and Spanish language responders in the HCHS/SOL Sociocultural Ancillary Study. Psychological Assessment, 29(3), 320–328. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000336

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Purba, A., & Demou, E. (2019). The relationship between organizational stressors and mental wellbeing within police officers: A systematic review. Bmc Public Health, 19, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7609-0

Queirós, C., Passos, F., Bártolo, A., Marques, A. J., da Silva, C. F., & Pereira, A. (2020). Officers: Literature review and a study with the operational police stress questionnaire. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00587

Quick, J., & Henderson, D. (2016). Occupational stress: Preventing suffering, enhancing wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13, 459–570. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13050459

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Sagar, M. H., Karim, A. R., & Nigar, N. (2014). Factor structure for organizational police stress questionnaire (PSQ-Org) in Bangladeshi culture. Universal Journal of Psychology, 2(9), 265–272. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujp.2014.020901

Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1996). Maslach burnout inventory-general survey. Manual. Consulting Psychologists.

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3, 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015630930326

Schmitt, T. A. (2011). Current methodological considerations in exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 29(4), 304–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282911406653

Smoktunowicz, E., Baka, L., Cieslak, R., Nichols, C. F., Benight, C. C., & Luszczynska, A. (2015). Explaining counterproductive work behaviors among police officers: The indirect effects of job demands are mediated by job burnout and moderated by job control and social support. Human Performance, 28, 332–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2015.1021045

Tarka, P. (2017). The comparison of estimation methods on the parameter estimates and fit indices in SEM model under 7-point likert scale. Archives of Data Science, 2(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.5445/KSP/1000058749/10

Vandenberg, R. J., & Lance, C. E. (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 3(1), 4–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810031002

Viladrich, C., Angulo-Brunet, A., & Doval, E. (2017). A journey around alpha and omega to estimate internal consistency reliability. Anales De Psicología, 33(3), 755–782. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.33.3.268401

Violanti, J. M., Charles, L. E., McCanlies, E., Hartley, T. A., Baughman, P., Andrew, M. E., … Burchfiel, C. M. (2017). Police stressors and health: A state-of-the-art review. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 40(4), 642–656. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-06-2016-0097

Vîrgă, D. (2015). Job insecurity and job satisfaction: The mediating effect of psychological capital. Psihologia Resurselor Umane, 13(2), 206–216. Retrieved from https://www.hrp-journal.com/index.php/pru/article/view/109

Vîrgă, D., Zaborilă, C., Sulea, C., & Maricuțoiu, L. (2009). Romanian adaptation of Utrecht work engagement scale: The examination of validity and reliability. Psihologia Resurselor Uman, 7, 58–74. https://doi.org/10.24837/pru.v7i1.402

Vîrgă, D., de Witte, H., & Cifre, E. (2017). The role of perceived employability, core self-evaluations, and job resources on health and turnover intentions. The Journal of Psychology, 151(7), 632–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2017.1372346

Willemin-Petignat, L., Anders, R., Ogi, S., & Putois, B. (2023). Validation and Psychometric properties of the German operational and organizational police stress questionnaires. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(19). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196831

Yu, C. Y., & Muthen, B. (2002). Evaluation of model fit indices for latent variable models with categorical and continuous outcomes. In the American Educational Research Association annual meeting, New Orleans, LA.

Zulkafaly, F., Kamaruddin, K., & Hassan, N. H. (2017). Coping strategies and job stress in policing: A literature review. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 7, 458–467. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i3/2749

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the institutional and/or national research committee’s ethical standards, the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments, or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Petreuș, AD., Vîrgă, D. & Okros, N. Psychometric properties and invariance of the Police Stress Questionnaire in the Romanian context. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06167-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06167-2