Abstract

Emotion as Social Information Theory claims that in an ambiguous situation, people rely on others’ emotions to make sense of the level of fairness encountered. We tested whether the information provided by emotions about the fairness of a procedure is still a significant factor in explaining individual differences in perception of variance, even in unambiguous situations. We assessed the effects of others’ emotions on observers inferred procedural justice during (un)ambiguous situations when people are treated (un)fairly. We collected data using Qualtrics online survey software from 1012 employees across different industry services in the United States. The participants were assigned randomly to one of the 12 experimental conditions (fair, unfair, and unknown x happiness, anger, guilt, and neutral). The results indicated that emotions played a significant role in the psychology of justice judgments under the ambiguous situation, as predicted by the EASI, as well as under unambiguous conditions. The study revealed significant interactions between the procedure and emotion. These findings emphasized the importance of considering how others’ emotions influence an observer’s perception of justice. The theoretical and practical implications of these findings were also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Emotion as Social Information Theory (EASI) proposes that individuals rely on others’ emotions to make sense of the level of fairness in an ambiguous situation. However, the theory provides no information when the situation is unambiguous. This study fills this gap and assesses if the information provided by emotions about the fairness of a situation can explain individual differences in perception of variance in unambiguous situations when people are treated fairly and unfairly. The study further assesses the possible moderation that emotions may play between the fairness of the procedure and the observer’s justice perception of that procedure.

An individual’s impression about the fairness of a given procedure comes not only from their direct personal experiences but also from observations of others’ treatment (Jones & Skarlicki, 2005; Mitchell et al., 2015; O’Reilly et al., 2016; van den Bos & Lind, 2001). The observer, a third party in the justice process, witnesses or learns about the (in)justice treatment faced by a recipient and subsequently forms their own justice perception (Fortin et al., 2015).

Empirical evidence shows that people make inferences about justice based on the emotions they perceive in others, even though they are not personally engaged in the justice dynamic (DeCremer et al., 2008; Hillebrandt & Barclay, 2017; Skarlicki & Kulik, 2005). The information carried by emotion is transmitted to the observers (Keltner et al., 1993), who receive and decode them (Shaver et al., 1987) and make inferences that disambiguate the situation (Fridlund, 1994; Manstead & Fischer, 2001), and subsequently, are influenced by those expressions (Hillebrandt & Barclay, 2017).

Procedural (in)justice was found to provoke emotions such as anger, disgust, happiness, shame, guilt, and pride (Cropanzano et al., 2011; Barclay et al., 2005; Hillebrandt & Barclay, 2013; Weiss et al., 1999). Each discrete emotion has a specific target and links with a specific evaluation of an event (Frijda, 1986; Lazarus, 1991; Scherer et al., 2001). For example, anger heightens sensitivity to injustice and communicates that the expressor feels that their goal is being obstructed by someone else and therefore blames them for it (Smith et al., 1993). Guilt signals that the person is sorry for the misdemeanor, which is associated with an over-advantageous or favorably biased procedure (Van Kleef, 2016; Weiss et al., 1999). Alternatively, happiness indicates that an individual recognizes the situation as favorable, has positive expectations, and achieves their goals (Fridlund, 1994; Lazarus, 1991; Weiss et al., 1999) noticed that individuals become happy due to the outcome but feel guilty due to the process by which the outcome was achieved. We chose these emotions because they represent the positive (happiness) and negative (anger and guilt) valence of emotional expression, and more research links them with procedural justice.

Observers’ intense reactions are strongly affected by unfair decisions as compared to that affected by fair decisions (e.g., Cremer & Ruiter, 2003). Unfair decisions significantly increase anger relative to fair decisions (Barclay et al., 2005; Cremer, 2004; Rupp & Spencer, 2006; Bies & Tripp, 2002) suggested that justice and injustice could be distinct constructs (see also Alkhadher & Gadelrab, 2022; Colquitt et al., 2015). Justice is an expected norm only noticed when something goes wrong (Cropanzano et al., 2011) because injustice violates employees’ expectations (Jones & Skarlicki, 2005), suggesting that injustice has more substantial effects on an individual’s behavior and well-being than the effects of justice.

According to the EASI, emotional expression provides information about the affective state of the transmitter, which may influence observers through inferential processes and/or affective reactions. To make judgements on procedural justice, individuals seek relevant information about a specific event. However, individuals often find themselves in ambiguous situations where no helpful information is available. The degree of uncertainty increases people’s need for justice information, motivating them to attend to the emotions expressed by others (Cremer et al., 2007). According to the uncertainty management model (Van den Bos & Lind, 2002), justice information is needed to cope with all types of uncertainties in our lives. Thus, a high degree of uncertainty motivates people to attend more easily to others’ emotions, particularly when these emotions signal justice-related information. The observer may use the information inferred from others when forming their own judgments as well as others’ evaluations of an event (Van Kleef, 2009; Kleef, 2016). These inferential processes are evident in negotiation settings (Van Kleef et al., 2006) and leader-follower interactions (Sy et al., 2005).

The notion that in an ambiguous situation, people rely on others’ emotions to make sense of the level of fairness encountered, as stated by the EASI theory, implies that in unambiguous situations, where sufficient information about the fairness of the procedures is available, people rely less on other emotions to understand the situation. That is, the level of the epistemic motivation (Kruglanski, 1989) of an individual expending effort and seeking more information to make sense of the world around them becomes low as sufficient information about the event is available (De Dreu et al., 2008). This situation suggests that emotions may have slight incremental variance in the fairness of an event, in addition to what an unambiguous (un)fair situation can offer. To the best of our knowledge, this notion has not yet been tested. Accordingly, we test the following hypothesis:

H1: Emotions (anger, guilt, happiness, and no emotion) will not add significant incremental variance in addition to what an unambiguous, fair, or unfair procedure could offer.

Justice and emotions are closely connected (Cremer & van den Bos, 2007). However, most studies have dealt with emotions (vs. mood or affects) as antecedents or consequences of procedural justice (Greenberg & Ganegoda, 2007). Few studies have considered emotions as moderators (Breugelmans & Cremer, 2007; Cremer et al., 2008) study was an exception. They gave participants no voice during the decision-making procedure and manipulated the ambiguity of an unfair procedure and the emotions (anger, shame) of a third party. Results of this study suggests a significant interaction between procedural justice by emotions; participants were angrier in the case of ambiguous procedures in the angry (vs. shame) condition. There are situations where the observer cannot access the expresser’s emotions. This may be because they have no direct interaction with the expressor who deliberately or inadvertently alters the emotions or masks them from reaching others. Therefore, the authors investigated potential procedural justice by happiness/anger interactions. In a fair situation, happiness signals that the outcome is favorable and justified (Fridlund, 1994; Lazarus, 1991). In an unfair situation, anger indicates an unfavorable outcome and that the goal is unfairly obstructed (Smith et al., 1993). When an individual is treated fairly, an observer is more prone to believe the expressed happiness emotion. When that individual is treated unfairly, the observer is more prone to believe the expressed anger emotion, as there is no reason to fake these emotions in these situations. Accordingly, we proposed the following hypotheses:

There is a significant interaction between emotion and procedure for the other’s procedural justice (H2a), as well as the observer’s own procedural justice (H2b). In a fair situation, happiness would significantly increase the justice perception of others (H2c) and the observer’s procedural justice (H2d) compared with anger. In an unfair situation, anger would significantly decrease the perception of others’ procedural justice (H2e) and the observer’s own procedural justice (H2f) compared with happiness.

Methods

Participants

We collected data using Qualtrics online survey software (Belliveau et al., 2022; Holtom et al., 2022) from 1012 participants in the United States (51% males; 74.2% graduates; age M = 48.8 yrs., SD = 15.2). To estimate the sample size for each condition group, we used power analysis with the following parameters: moderate effect size, alpha = 0.01, power = 0.9 for main and interaction effects for ANOVA given the research design. Meta-analysis results (see Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001) reported moderate effect size estimates in justice research. Therefore, a moderate effect size is considered meaningful and practically significant. We start with a reasonably ambitious but realistic hypothesized effect size. We set alpha to 0.01 and power to 0.90 instead of 0.05 and 0.80, which is more common in practice, to minimize the combined Type 1 and Type 2 error rates. Power analysis revealed that 85 participants are needed for each condition. The number of participants who responded for each condition ranged from 83 to 85.

The participants were full-time employees across different industry services, excluding military-type organizations (17.1.% health care and social; 15.4% retail and food; 8.7% academic and educational; 5.7% finance, banking, and insurance; 4.8% agriculture and manufacturing; 47.7% others). They belonged to government (16.7%), private (69.8%), and non-profit (13.5%) work sectors (tenure M = 26.6 yrs., SD = 15.3), and represented various races (69.3% White or Caucasian, 15.0% Black or African American, 5.2% Asian, 0.6% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 0.9% American Indian, and 9.0% others). They participated voluntarily in the study, and their responses were anonymous.

Measures

The other’s (candidate’s) procedural justice was measured as the mean of 8 items, seven of which were adapted from Colquitt (2001) and modified to fit the context of our study. This measure is widely used compared to other local once (Alkhadher & Gadelrab, 2016; Gadelrab et al., 2000). We added a new item (item 8, Appendix A) to the accurate information rule since accurate information can be differentiated from expert opinion. Participants were asked to carefully read a scenario specified to them and answer questions related to it. All items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was 0.94.

The observer’s procedural justice was measured as the mean of 8 items, seven of which were modified from Colquitt (2001) to fit the context of our study. We added a new question (item 8, Appendix B) to the accurate information rule since accurate information can be differentiated from expert opinion. After completing the previous measure, the participants were asked to answer the eight items; All items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was 0.97.

Affect was measured using the short version of Watson and Clark’s Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Mackinnon et al., 1999). The measure has ten items that describe different feelings and emotions (inspired, afraid, alert, upset, excited, nervous, enthusiastic, scared, determined, and distressed). The scale has five points ranging from 1 (“Very slightly or not at all”) to 5 (“Extremely”). The alpha coefficient values were 0.81 for positive and 0.91 for negative affect, respectively.

Job Satisfaction was measured using one item assessing how satisfied the participant was with their current job. Many studies have investigated the suitability of using a single item to assess general job satisfaction (see Wanous et al., 1997 for meta-study). The item read: “How satisfied are you with your current job?“. The scale had 11 points, ranging from 0 (“not at all”) to 10 (“Extremely”).

Demographic data about the employee’s gender, age, ethnicity, tenure, and work sector were also collected.

Procedure

To test the hypotheses, we randomly assigned the participants to one of the 12 experimental conditions (three procedural justice levels [fair, unfair, no information] × four emotions [happiness, anger, guilt, no emotion]). We assigned 85 participants to each group. They were told that the goal of the study was to help learn more about how employees perceive fairness in their work environment. They were first asked to fill in their demographic data, followed by the PANAS to partial out the possible effects of affect. The participants were then asked to read a vignette according to their assigned condition, followed by comprehension checks (Appendix C). Each vignette was carefully written to reflect all six rules of Leventhal for procedural justice (1980). The scenarios were then examined for their construct validity by expert raters, after which they were modified several times until inter-rater agreements were above 80%. The raters assessed the accuracy of each scenario using Leventhal’s criteria and how differentiated each scenario was from the other.

The social signaling value of emotions was functionally equivalent across expressive modalities such as facial, written or spoken words, tone of voice, bodily postures, or symbols (de Melo et al., 2014; Gray et al., 2017; Wingenbach et al., 2019). Accordingly, written scenarios are capable of conveying expressed emotions. In the scenarios, we controlled for the genders of the recipient, observer, manager, and secretary. The vignette asks the participant (employee) to read an imaginary scenario where he/she came to the manager’s secretary’s office to speak with his/her manager. The secretary replied that the manager is busy meeting with a new job candidate. The participants were able to hear what was going on in the manager’s room (Fair/unfair/no information procedure). The participant noticed the candidate leaving the interview [smiled/scowled/ looked downward] and said he/she filet [happy/angry/guilty]. For no emotion, no facial expression nor word of emotion was expressed.

As comprehension check, participants were asked to indicate whether the procedure the manager followed was fair/unfair/unclear and to specify the emotion expressed by the candidate as happiness/anger/guilt/no emotion. Participants who identified a wrong emotion or fairness condition or identified as a speeder (those who responded with less than the minimum response time) were excluded. Finally, the participants were asked to fill out the procedural justice measures of the candidate and the observer.

Data analysis

No missing data were found; however, only eight respondents have been identified with response sets and considered as outliers; therefore, they have been removed from the final analysis. Accordingly, the total number of participants for each condition ranged from 83 to 85. Job satisfaction and positive mood were controlled to eliminate any possible effects on the perception of procedural justice (Table 1). Age, experience, and negative mood showed no relationship with procedural justice. As the other’s procedural justice and the observer’s procedural justices were correlated (r = .84, p < .001), we used Mplus@8.0 to perform a confirmatory factor analysis. We used the maximum likelihood parametric estimates with standard error and a mean and variance adjusted X2 test of model fit (MLMV), which is robust to data non-normality (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). The goodness-of-fit index of the two-factor model reached an acceptable level, showing good discriminant validity (X2 = 563.33, p = .000, df = 103, CFI = 0.934, TLI = 0.924, RMSEA = 0.066, SRMR = 0.028). The one-factor model showed a poor fit (X2 = 975, p = .000, df = 104, CFI = 0.876, TLI = 0.857, RMSEA = 0.091, SRMR = 0.049). We focused only on fair and unfair conditions in testing H2c − f because they make the most sense theoretically, as finding evidence for moderation in unambiguous situations would present the greatest challenge for the EASI model. Accordingly, we exclude participants in ambiguous conditions for testing these hypotheses. The data supporting the findings of this study can be accessed at: https://osf.io/uey8k/?view_only=69297d56e8a34e22bd09c7adea3075d9.

Results

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations (SDs), correlations, and reliabilities among the selected variable scores. As expected, a high correlation was found between the other’s procedural justice (as perceived by the observer) and the observer’s procedural justice (0.84, p < .001). Job satisfaction correlated with other’s procedural justice (0.13; p < .01) and observer’s procedural justice (0.16; p < .01). Additionally, positive mood correlated with other’s procedural justice (0.14; p < .01) and observer’s procedural justice (0.11; p < .01). No correlations were found for age, experience, and negative mood on either justice scale.

Based on the previous theoretical frame, we first tested the EASI’s claim that people rely on others’ emotions to make sense of the level of fairness encountered in an ambiguous situation. Accordingly, it is expected that in ambiguous situations, emotions (anger, guilt, happiness, and no emotion) explain a significant amount of others’ procedural justice variance (as inferred by the observer) and the observer’s own procedural justice. We used data from only those participants who received no information about the procedure used (N = 340). We performed a hierarchical regression for perceived other’s (candidate’s) procedural justice and observer’s procedural justice, controlling for job satisfaction and positive mood, as both correlate with justice. For both justices, emotions explained significant variance in the absence of any information about the fairness of the procedure (ΔR2 = 0.183 for the other’s justice and 0.076 for the observer’s procedural justice, at p < .001; see Table 2). The magnitude depended on the type of emotion and procedural justice (for others or observers). These results indicate that these justice perceptions differ as a function of their respective conditions (e.g., low in anger conditions and high in happiness conditions). Table 3 provides mean differences among emotions in the case of other’s and observer’s procedural justices. All emotions used in the study significantly differ in perception of procedural justice (Table 3). The results supported the EASI theory that emotion acts as social information in ambiguous situations.

Based on this result, we tested our first hypothesis that emotions (anger, guilt, happiness, and no emotion) will not add significant incremental variance in addition to what an unambiguous, fair, or unfair procedure could offer. We performed a hierarchical regression for perceived others’ as well as observer’s procedural justices, controlling for job satisfaction and positive mood. As shown in Step 3 in Table 4, for predicted other’s procedural justice, inserting emotion added a 5.2% significant variance (β = 0.09 for happiness, − 0.19 for anger, and − 0.06 for guilt) in addition to what procedure (fair and unfair) had contributed. For the observer’s procedural justice, inserting emotion added significant variance, though small 0.8% (β = 0.06 for happiness, and − 0.05 for anger) in addition to what procedure had contributed. Emotions could still contribute significant incremental variance in predicting procedural justice, whether the procedure was fair or unfair. However, the magnitude depended on the type of emotion and justice assessed. This result challenges the EASI theory and supports the role of emotion in an unambiguous situation, a case which has not been tested before.

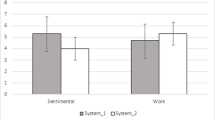

Hypothesis H2a − f investigated the possible interaction between emotion and procedure for others as well as the observer’s procedural justices (Figs. 1 and 2). ANOVA results (Table 5) showed a significant interaction between procedure and emotion for other’s procedural justice (F = 6.44, p < .001; η2 = 0.04) and observer’s procedural justice (F = 3.62, p < .001; η2 = 0.02). These results supported both H2a and H2b.

Simple effects for fair and unfair scenarios (Table 6) revealed a different effect pattern for fair and unfair situations. In a fair situation, happiness significantly increases the perception of others and the observer’s own procedural justice compared with anger. Perceptions of procedural justice were significantly higher in the happiness conditions compared to anger conditions, both for other’s procedural justice (F = 32.27, p < .001; η2 = 0.23) and observer’s procedural justice (F = 3.33, p < .05; η2 = 0.03). Thus, H2c and H2d were supported. In an unfair situation, though procedural justice ratings were lower in the anger compared to the happiness conditions for others’ and observer’s justice, the difference was not large enough to be significant. The emotions effect on procedural justice perceptions (F = 2.74, p < .05; η2 = 0.03) was shown to be driven by the difference between the neutral and guilt conditions. Thus, H2e and H2f were not supported.

Discussion

This study investigated if emotions contribute significantly to justice perceptions, above and beyond what is provided by the procedure itself. The study assessed the effects of others’ emotions on the observer’s inferred procedural justice during unambiguously fair and unfair situations. It also extended the previous line of research by investigating the potential interaction between emotions and the fairness of an event on the observer’s judgment about one’s own and others’ procedural justice perceptions. The results of this study revealed that emotions played a significant role in the psychology of justice judgments, not just under uncertain conditions, as predicted by the EASI theory, but also under certain conditions. The study also found significant interactions between the procedure and emotion.

Theoretical contributions

This study provides notable theoretical contributions. First, the results support the EASI theory showing that emotions could explain significant variance in the absence of any information about the fairness of the procedure. Second, emotions added significant incremental variance to the other’s (candidate’s) as well as the observer’s (own) procedural justice beyond what an unambiguous (un)fair situation can offer (H1, Table 4). This suggests that emotions could play a significant role in predicting procedural justice, even when the situation is specific. This result provides a limitation to the EASI theory. However, the amount of variance explained by emotions was less than that explained by the (un)fair procedure. This may contradict Van den Bos (2003) finding that when the procedure is unambiguous, an individual’s affective states have statistically non-significant effects. The contradiction could be attributed to the fact that the current study assessed justice judgement as perceived by an observer, not the individual who received the (un)fair act.

Third, the results reveal that emotion can be a potential moderator between (un)fair procedures and a justice’s perception of that procedure when assessing others’ and own procedural justices (Tables 5 and 6). In a fair situation, compared with anger, happiness significantly increases the perception of justice (Figs. 1 and 2). In unfair situations, people rely more upon the procedure of the situation and less on others’ emotions. The unfairness is strong enough to make the observer almost ignore others’ emotions.

Fourth, with fair treatment, happiness increases the perception of procedural justice, as happiness is the most likely emotion in this situation. In an unfair situation, happiness expression is unexpected and inappropriate and may reveal an ironic expression for the unfair treatment. Emotions perceived as inappropriate violate prevailing norms and may elicit negative emotions in observers (Bucy, 2000). For example, Côté et al. (2013) found in an experimental study that expressing anger in a fair situation could be perceived as dishonest, irrelevant, and manipulative. In this situation, the observer may decide to ignore and not respond to the emotion of the expressor.

Fifth, and finally, the interaction between procedure and emotions revealed a different pattern in fair and unfair situations. Suggesting that justice and injustice may not be merely interchangeable; thus, injustice may not be treated as the opposite of justice (Alkhadher & Gadelrab, 2022; Colquitt et al., 2015).

Implications

This study has several practical implications. The results drew our attention to the importance of fair procedures and policies toward external parties, such as applicants, vendors, or customs, as this may affect the perception of fairness of their internal parties. Employees do not have to communicate among themselves to share their perceptions of justice. An employee who witnesses others mistreated may experience injustice even when they are personally treated relatively. Accordingly, decision-makers should review their organizational policies toward external parties to eliminate any biases.

The exact mechanism is applied internally among teamwork members (Cheshin et al., 2011). Emotions expressed by one member toward authority may directly affect others’ perceptions of justice, even if there is no direct interaction with them. Additionally, in an actual situation, newcomers usually face ambiguous situations that motivate them to use the emotional displays of another group member to make sense of the situation (Wubben et al., 2008). As suggested by this study, justice judgments can be socially constructed. Therefore, the social effects of emotions within justice contexts should be acknowledged by authorities.

Strengths and Limitations

We included all the procedural justice criteria, as identified by Leventhal (1980), when constructing the vignettes and reflecting them in the measures used and did not just focus on one aspect of procedural justice, such as voice (Cremer et al., 2008). However, we could not relate emotion’s effect to each procedural justice component (Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001). These results provide content validity to the constructed vignettes used in this study. The scenarios were controlled for the gender of all actors. However, future studies may want to explore the effects of the gender of the manager, observer, or candidate, as well as their race and color on justice perception. Future research may also manipulate the scenario to different variations, such as emotion intensity (Barclay & Whiteside, 2011), to investigate theoretical-based questions.

Nevertheless, the current study has some limitations. First, at the time of data collection, between May and September 2021, COVID-19 continued to spread in the US, causing deaths and economic hardships. It is reasonable to think that such a health crisis may affect participants’ perceptions when filling out the questionnaires. Second, the experimental design provides no information about the fairness of the procedure in one of the conditions. One may argue that there is a difference between an ambiguous and no information (unknown) procedure in terms of fairness.

Conclusion

Our findings highlight the importance of others’ emotions as social information, the subjective nature of justice judgment, and that justice perceptions are not merely a result of deliberate cognitive processes. We showed that emotions play a significant role in justice judgments, under certain as well as uncertain conditions, with fair and unfair procedures, even when the observers were themselves not mistreated. The study also emphasized the role of emotion as a potential moderator between (un)fair procedures and justice perception of that procedure when assessing self as well as others’ procedural justices.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study, as well as the informed consent, can be accessed at: https://osf.io/uey8k/?view_only=69297d56e8a34e22bd09c7adea3075d9.

References

Alkhadher, O., & Gadelrab, H. (2016). Organizational justice dimensions: Validation of an arabic measure. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 24(4), 337–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12152

Alkhadher, O. H., & Gadelrab, H. F. (2022). Differential predictions of Organizational Justice and Injustice: Contribution of injustice in Prevention-Laden Outcomes. Trends in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-022-00248-6

Barclay, L. J., & Whiteside, D. B. (2011). Moving beyond (in)justice perceptions: Examining the roles of experience and intensity. In S. W. Gilliland, D. D. Steiner, & D. P. Skarlicki (Eds.), Research in social issues in management. Emerging perspectives on organizational justice and ethics (pp. 49–74). Information Age Publishing.

Barclay, L. J., Skarlicki, D. P., & Pugh, S. D. (2005). Exploring the role of emotions in injustice perceptions and retaliation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(4), 629–643. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.4.629

Belliveau, J., Soucy, K. I., & Yakovenko, I. (2022). The validity of Qualtrics panel data for research on video gaming and gaming disorder. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/pha0000575

Bies, R. J., & Tripp, T. M. (2002). Hot flashes and open wounds: Injustice and the tyranny of its emotions. In S. W. Gilliland, D. D. Steiner, & D. P. Skarlicki (Eds.), Emerging perspectives on managing organizational justice (pp. 203–221). Information Age Publishing.

Breugelmans, S., & De Cremer, D. (2007). The role of emotions in cross-cultural justice research. In De D. Cremer (Ed.), Advances in psychology of justice and affect (pp. 83–104). Information Age Publishing.

Bucy, E. P. (2000). Emotional and evaluative consequences of Inappropriate Leader Displays. Communication Research, 27(2), 194–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365000027002004

Cheshin, A., Rafaeli, A., & Bos, N. (2011). Anger and happiness in virtual teams: Emotional influences of text and behavior on others’ affect in the absence of non-verbal cues. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 116(1), 2–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2011.06.002

Cohen-Charash, Y., & Spector, P. E. (2001). The role of Justice in Organizations: A Meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86(2), 278–321. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.2001.2958

Colquitt, J. A. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 386–400. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.386

Colquitt, J. A., Long, D. M., Rodell, J. B., & Halvorsen-Ganepola, M. D. K. (2015). Adding the “in” to justice: A qualitative and quantitative investigation of the differential effects of justice rule adherence and violation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(2), 278–297. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038131

Côté, S., Hideg, I., & van Kleef, G. A. (2013). The consequences of faking anger in negotiations. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(3), 453–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.12.015

Cropanzano, R., Stein, J. H., & Nadisic, T. (2011). Social justice and the experience of emotion. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

De Cremer, D. (2004). The influence of accuracy as a function of leader’s bias: The role of trustworthiness in the psychology of procedural justice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(3), 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203256969

De Cremer, D., & Ruiter, R. A. C. (2003). Emotional reactions toward Procedural Fairness as a function of negative information. The Journal of Social Psychology, 143(6), 793–795. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540309600433

De Cremer, D., & van den Bos, K. (2007). Justice and feelings: Toward a new era in Justice Research. Social Justice Research, 20(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-007-0031-2

De Cremer, D., van Kleef, G., & Wubben, M. J. J. (2007). Do the emotions of others shape justice effects? An interpersonal approach. In De D. Cremer (Ed.), Advances in the psychology of justice and affect (pp. 35–57). Information Age Publishing.

De Cremer, D., Wubben, M. J. J., & Brebels, L. (2008). When unfair treatment leads to anger: The effects of other people’s emotions and ambiguous unfair procedures. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 38, 2518–2549. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2008.00402.x

De Dreu, C. K. W., Nijstad, B. A., & van Knippenberg, D. (2008). Motivated information processing in group judgment and decision making. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12(1), 22–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868307304092

de Melo, C. M., Carnevale, P. J., Read, S. J., & Gratch, J. (2014). Reading people’s minds from emotion expressions in interdependent decision making. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(1), 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034251

Fortin, M., Blader, S. L., Wiesenfeld, B. M., & Wheeler-Smith, S. L. (2015). Justice and affect a dimensional approach. In M. Ambrose & R. Cropanzano (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Justice in the Workplace (pp. 419–439). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199981410.001.0001

Fridlund, A. J. (1994). Human facial expression: An evolutionary view. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.32-3890

Frijda, N. H. (1986). The emotions. Cambridge University Press.

Gadelrab, H. F., Alkhadher, O., Aldhafri, S., Almoshawah, S., Khatatba, Y., Abiddine, E., Alyatama, F. Z., Almsalak, M., Tarboush, S., & Slimene, N., S (2020). Organizational Justice in Arab Countries: Investigation of the measurement and structural invariance. Cross-Cultural Research, 54(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397118815099

Gray, D., Royall, B., & Malson, H. (2017). Hypothetically speaking: Using vignettes as a stand-alone qualitative method. In V. Braun, V. Clarke, & D. Gray (Eds.), Collecting qualitative data: A practical guide to Textual, Media and virtual techniques. Cambridge University Press.

Greenberg, J., & Ganegoda, D. B. (2007). Justice and affect: Where do we stand? In De D. Cremer (Ed.), Advances in the psychology of justice and affect (pp. 261–292). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Hillebrandt, A., & Barclay, L. J. (2013). Integrating organizational justice and affect: New insights, challenges, and opportunities. Social Justice Research, 26(4), 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-013-0193-z

Hillebrandt, A., & Barclay, L. J. (2017). Observing others’ anger and guilt can make you feel unfairly treated: The interpersonal effects of emotions on justice-related reactions. Social Justice Research, 30(3), 238–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-017-0290-5

Holtom, B., Baruch, Y., Aguinis, H., & Ballinger, A., G (2022). Survey response rates: Trends and a validity assessment framework. Human Relations. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267211070769

Jones, D. A., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2005). The effects of overhearing peers discuss an authority’s fairness reputation on reactions to subsequent treatment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(2), 363–372. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.2.363

Keltner, D., Ellsworth, P. C., & Edwards, K. (1993). Beyond simple pessimism: Effects of sadness and anger on social perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(5), 740–752. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.64.5.740

Kruglanski, A. W. (1989). Perspectives in social psychology. Lay epistemic and human knowledge: Cognitive and motivational bases. Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.27-4159

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. Oxford University Press.

Leventhal, G. S. (1980). What should be done with equity theory? New approaches to the study of fairness in social relationships. In K. J. Gergen, M. S. Greenberg, & R. H. Willis (Eds.), Social exchange: Advances in theory and research (pp. 27–55). Plenum. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-3087-5_2

Mackinnon, A., Jorm, A. F., Christensen, H., Korten, A. E., Jacomb, P. A., & Rodgers, B. (1999). A short form of the positive and negative affect schedule: Evaluation of factorial validity and invariance across demographic variables in a community sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 27(3), 405–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0191-8869(98)00251-7

Manstead, A. S. R., & Fischer, A. H. (2001). Social appraisal: The social world as object of and influence on appraisal processes. In K. R. Scherer, A. Schorr, & T. Johnstone (Eds.), Series in affective science. Appraisal processes in emotion: Theory, methods, research (pp. 221–232). Oxford University Press.

Mitchell, M. S., Vogel, R. M., & Folger, R. (2015). Third parties’ reactions to the abusive supervision of coworkers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(4), 1040–1055. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000002

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus User’s Guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

O’Reilly, J., Aquino, K., & Skarlicki, D. (2016). The lives of others: Third parties’ responses to others’ injustice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(2), 171–189. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000040

Rupp, D. E., & Spencer, S. (2006). When customers lash out: The effects of customer interactional injustice on emotional labor and the mediating role of discrete emotions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(4), 971–978. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.971

Scherer, K. R., Schorr, A., & Johnstone, T. (Eds.). (2001). Appraisal processes in emotion: Theory, methods, research. Oxford University Press.

Shaver, P., Schwartz, J., Kirson, D., & O’Connor, C. (1987). Emotion knowledge: Further exploration of a prototype approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(6), 1061–1086. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.6.1061

Skarlicki, D. P., & Kulik, C. T. (2005). Third-party reactions to employee (mis)treatment: A justice perspective. In B. M. Staw & R. M. Kramer (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior: An annual series of analytical essays and critical reviews, Vol. 26, (pp. 183–229). Elsevier Science. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(04)26005-1

Smith, C. A., Haynes, K. N., Lazarus, R. S., & Pope, L. K. (1993). In search of the “hot” cognitions: Attributions, appraisals, and their relation to emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(5), 916–929. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.5.916

Sy, T., Côté, S., & Saavedra, R. (2005). The Contagious Leader: Impact of the leader’s mood on the mood of group members, group affective tone, and group processes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(2), 295–305. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.2.295

Van den Bos, K. (2003). On the subjective quality of Social Justice: The role of affect as information in the psychology of Justice Judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(3), 482–498. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.3.482

Van den Bos, K., & Lind, E. A. (2001). The psychology of own versus Others’ treatment: Self-oriented and other-oriented effects on perceptions of procedural justice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(10), 1324–1333. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672012710008

Van den Bos, K., & Lind, E. A. (2002). Uncertainty management by means of fairness judgments. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology,34, 1–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-2601(02)80003-x

Van Kleef, G. A. (2009). How emotions regulate social life: The emotions as social information (EASI) model. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(3), 184–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01633.x

Van Kleef, G. A. (2016). The interpersonal dynamics of emotion: Toward an integrative theory of emotions as social information. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107261396

Van Kleef, G. A., De Dreu, C. K. W., & Manstead, A. S. (2006). Supplication and appeasement in conflict and negotiation: The interpersonal effects of disappointment, worry, guilt, and regret. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91,124–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.1.124

Wanous, J. P., Reichers, A. E., & Hudy, M. J. (1997). Overall job satisfaction: How good are single-item measures? Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(2), 247–252. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.82.2.247

Weiss, H. M., Suckow, K., & Cropanzano, R. (1999). Effects of justice conditions on discrete emotions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(5), 786–794. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.84.5.786

Wingenbach, T. S. H., Morello, L. Y., Hack, A. L., & Boggio, P. S. (2019). Development and validation of verbal emotion vignettes in Portuguese, English, and german. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01135

Wubben, M. J. J., De Cremer, D., & van Dijk, E. (2008). When emotions of others affect decisions in public good dilemmas: An instrumental view. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38(5), 823–835. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.531

Acknowledgements

This work was supported and funded by Kuwait University Research Grant No. OP02/19. We would like to thank prof. Soyeon Ahn at the Department of Educational and Psychology Studies, and University of Miami for their support, and Editage for English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical statement

This study obtained institutional review board approval from the University of Miami (IRB ID 20210305).

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix A

Please choose the number that best reflects how the candidate (not yourself) likely perceived each of the statements below about the procedure the manager followed in the above scenario.

Items | Strongly Disagree | Strongly Agree | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | The candidate perceived that they could express their views and feelings during the procedure. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

2 | The candidate perceived that they could influence the decision arrived at by the procedure. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

3 | The candidate perceived that the procedure was applied consistently across all candidates. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

4 | The candidate perceived that the procedure was free of, or reduced, bias in the process. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

5 | The candidate perceived that the procedure was based on accurate information. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

6 | The candidate perceived that they were able to appeal the decision arrived at by the procedure. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

7 | The candidate perceived that the procedure was consistent with their own ethical and moral standards. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

8 | The candidate perceived that the procedure was based on expert opinion. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

Appendix B

Please choose the number that best reflects how you (not the candidate) assess each of the statements below about the procedure the manager followed in the above scenario.

Items | Strongly Disagree | Strongly Agree | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | The procedure allowed the candidate to express their views and feelings. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

2 | The procedure gave the candidate a chance to influence the decision. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

3 | The procedure was applied consistently across all candidates. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

4 | The procedure was free of or reduced, bias in the process. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

5 | The procedure was based on accurate information. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

6 | The procedure gave the candidate a chance to appeal the decision. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

7 | The procedure was consistent with your own ethical and moral standards. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

8 | The procedure was based on expert opinion. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

Appendix C

Fair with emotion scenario

Please read the scenario below carefully and answer the following questions related to it.

You came to your manager’s secretary’s office to request to speak to your manager. The secretary informed you that the manager has just begun meeting with a new job candidate, and the meeting will last 20 minutes. You were able to hear what was going on in the manager’s room. You heard the manager communicating to the candidate: “The documents that you’ve submitted are correct, up-to-date, and complete with all the necessary information. That will allow us to evaluate your application comprehensively. To ensure the process is properly conducted, the human resources manager will be consulted and provide input throughout the process. Is there anything else you would like to tell us or additional information you want us to consider in this interview? We take all your input seriously.” The candidate replied: “No, thanks.” The manager continued: “Sure, if anything comes to mind, please feel free to share it with me or the HR manager at any time. Here is a copy of the criteria that you will be evaluated by. These criteria are meant to evaluate all aspects of your application. For your own records, you will receive your results on each of these criteria. Every candidate goes through an identical evaluation process and has the right to petition for their evaluation should they disagree. In case of a petition, higher management will review the process.” The candidate concluded: “I appreciate the hiring process was conducted fairly; it resonates with my own values.” The manager replied: “Thank you for sharing your opinion on how the process was conducted.” The interview lasted the entire period for which it was scheduled.

After leaving the interview, you overheard the secretary ask the candidate how they felt. The candidate turned to the secretary, [smiled/scowled/ looked downward], and said: “I feel [happy/angry/guilty].”

For neutral, no facial expression nor word of emotion was expressed.

Unfair with emotion scenario

Please read the scenario below carefully and answer the following questions related to it.

You came to your manager’s secretary’s office to request to speak to your manager. The secretary informed you that the manager has just begun meeting with a new job candidate, and the meeting will last 20 minutes. You were able to hear what’s going on in the manager’s room. You heard the manager communicating to the candidate: “The application that you’ve submitted is incorrect, outdated, and missing essential information.” And before the candidate could reply, the manager continued: “The human resources manager won’t be consulted throughout the process and I’m unwilling to consider anything further. With a couple of other job interviews taking longer than expected, we will not continue with this interview. Based on what I can infer from your application, I only trust my own judgment to make this evaluation. My decision is final. You are not entitled to petition the decision.” The candidate concluded: “I don’t believe the hiring process was conducted fairly; it doesn’t resonate with my own values …”. The manager interrupted: “Thank you for your time; the meeting is over.” The interview ended earlier than the allotted time. After leaving the interview, you overheard the secretary ask the candidate how they felt. The candidate turned to the secretary, [smiled/scowled/ looked downward], and said: “I feel [happy/angry/guilty].”

For neutral, no facial expression nor word of emotion was expressed.

No information about the procedure with emotion scenario

Please read the scenario below carefully and answer the following questions related to it.

You came to your manager’s secretary’s office to request to speak to your manager. The secretary informed you that the manager has just begun meeting with a new job candidate, and the meeting will last 20 min. You don’t know what’s going on in the meeting. After leaving the interview, you overheard the secretary ask the candidate how they felt. The candidate turned to the secretary, [smiled/scowled/ looked downward], and said: “I feel [happy/angry guilty]”.

For neutral, no facial expression nor word of emotion was expressed.

Comprehension checks

The correct answer for the below two questions can be found in the scenario above. If you answer incorrectly, you will be terminated from the study.

-

1.

Which of the following emotions the candidate expressed to the secretary?

□Happiness □Anger □Guilt □Cannot determine.

-

2.

How do you judge the fairness of the procedure followed by the manager in the interview?

□ Fair □ Unfair □ Cannot determine.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Alkhadher, O.H., Gadelrab, H.F. & Alawadi, S. Emotions as social information in unambiguous situations: role of emotions on procedural justice perception. Curr Psychol 43, 5753–5764 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04640-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04640-y