Abstract

Based on Belsky’s process of parenting model and its recent update, the present study aims to explore multiple determinants of mindful parenting (i.e., parents’ psychological distress, child negative emotionality, and parental social support) across the UK and Türkiye using a multi-informant approach and multiple-group path analysis. We considered both parents’ and children’s perceptions of mindful parenting to obtain a complete picture of the mindful parenting process within families. Parents and their children aged 11–16 years were recruited in the UK (N = 101, Mchild age = 13.06 years, SDchild age = 1.64 years) and Türkiye (N = 162, Mchild age = 13.28 years, SDchild age = 1.65 years). Multiple-group path analysis revealed that both parent and child perspectives of mindful parenting are multiply determined. Parental psychological distress mediated the associations of child negative emotionality and social support with mindful parenting in both cultures. However, child negative emotionality was a direct determinant of mindful parenting in the UK only. Overall, our study shed light on both individual and cultural differences in the mindful parenting process. Limitations of the current research and recommendations and implications for future mindful parenting research and practices were discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Mindful parenting --non-judgmental and present-centred awareness in parent-child interactions– has been a subject of considerable interest during the last decade (Duncan et al., 2009). Studies have revealed that mindful parenting remarkably reduces children’s internalising and externalising behaviours while promoting prosocial behaviours (e.g., Cheung et al., 2021; Wong et al., 2019) and life satisfaction (Liu et al., 2021). As such, it has become crucial to identify the sources of individual differences in mindful parenting. Here, building on the process of the parenting model (Belsky, 1984; Taraban & Shaw, 2018), we suggested a model of the determinants of mindful parenting, namely, a process of mindful parenting model. We empirically tested the direct and indirect associations of parent characteristics, child characteristics, and family social environment with mindful parenting, exploring the moderating role of culture. Moreover, further extending previous literature, we included both child and parent perspectives of mindful parenting.

Mindful parenting

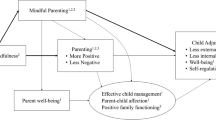

Duncan et al. (2009) define mindful parenting as parental attention to parent-child interaction, as well as compassionate, non-reactive, and non-judgemental parental awareness and acceptance of self and child. They suggest that mindful parenting promotes child management and parenting practices, parent-child affection, and parental well-being and ultimately influences child outcomes, especially during the transition to adolescence (Duncan et al., 2009). Various studies have found small-to-moderate positive effects of mindful parenting interventions on children’s outcomes (i.e., internalising and externalising symptoms; Bögels et al., 2014; Emerson et al., 2021; Meppelink et al., 2016; Potharst et al., 2019). However, our understanding of the mindful parenting process lags behind the broader parenting literature, particularly since little is known about the determinants of mindful parenting. This may be partly due to the silent assumption that the determinants of mindful parenting are similar to those of other kinds of parenting behaviour (e.g., Baumrind, 1966; Parent & Forehand, 2017). Yet, mindful parenting behaviours are seen as distinct from these other parenting behaviours – hereon we refer to mindful parenting and ‘traditional models of parenting’, as per Duncan et al. (2009)’s conceptualisation and as is commonly used in the mindful parenting literature (Geurtzen et al., 2015; Pan et al., 2019) -- and we argue that this assumption should be tested empirically. First, mindful parenting concerns monitoring and controlling one’s own emotions, behaviours, and attention as a parent during parent-child interaction, whereas more traditional models of parenting refer to those of children. Second, mindful parenting describes “here-and-now” parenting, where parents pay deliberate attention to parent-child interaction; thus, it requires fundamental mindfulness skills (Duncan et al., 2009). Finally, mindful parenting sees parenting as a journey parents learn from their children, whilst the more traditional approaches tend to assume parents are the ‘experts’ (Kabat-Zinn & Kabat-Zinn, 1997).

Moreover, to our best knowledge, no study has examined the determinants of children’s perceptions of mindful parenting, although previous research on the traditional parenting models showed differences between the determinants of parent and child perceptions of parenting (Cheung & Theule, 2019; Gerdes et al., 2003, 2007). We aimed to fill this research gap, using multiple informants of mindful parenting (i.g., parents and their children) to identify the determinants of mindful parenting. For two main reasons, it is important to assess different perspectives on mindful parenting in this context. First, a multi-informant approach allows the examination of determinants of mindful parenting as perceived from both sides of the relationship. This affords a more complete picture of the mindful parenting process in families, accounting for the subjectivity of experience (Boyce et al., 1998; Schaefer, 1965). Children’s subjective experiences of parenting are robust predictors of child outcomes (Danese & Widom, 2020; Zhou et al., 2021), and identifying determinants of child-reported mindful parenting may improve our understanding. Second, a multi-informant approach may also increase the validity of the mindful parenting process model by minimising bias in self-report of parenting (Morsbach & Prinz, 2006; Schofield et al., 2016) and common-method variance where determinants are also parent-reported (Burk & Laursen, 2010). As such, simultaneously uncovering the determinants of parent and child perceptions of mindful parenting is essential for understanding the full picture of the mindful parenting process in families.

Determinants of (mindful) parenting

Belsky (1984) established a ground-breaking theoretical framework for explaining the determinants of parenting, positing that parenting is multiply determined by parent characteristics (e.g., personality, psychopathology), child characteristics (e.g., temperament), and family social environment (e.g., marital quality, social support). The current study focuses on the determinant roles of parental psychological well-being, child negative emotionality, and social support, as well as potential mechanistic pathways for mindful parenting.

According to Belsky (1984), parental psychological well-being is central to the parenting process, in part directly influencing parenting. Indeed, empirical research has supported parental psychological distress (e.g., depression) as a parental risk factor for maladaptive fathering (for meta-analysis, see Cheung & Theule 2019) and mothering (for meta-analysis, see Goodman et al., 2020; Lovejoy et al., 2000). For mindful parenting, studies have revealed that parental psychological distress can also be undermining (e.g., Cheung et al., 2021; Corthorn & Milicic, 2016; de Bruin et al., 2014; Fernandes et al., 2021; Henrichs et al., 2021). It is suggested that parental psychological distress threatens mindful parenting by impairing capabilities in essential features of mindful parenting, such as emotion regulation, awareness, and present-moment attention. For instance, parents with psychological distress may be less likely to self-regulate during parent-child interaction due to their impaired emotion regulation skills (Kerns et al., 2017; Lovejoy et al., 2000). In addition, parents with higher depressive symptoms may be less attuned and sensitive in their parenting interaction and, as such, be less able to notice emotions of themselves and those of their children (Coyne et al., 2007; Lovejoy et al., 2000) as well as being less aware of the impact of their behaviours on their children’s emotions (Coyne et al., 2007).

In terms of direct effects on parenting, child characteristics, particularly child temperament, are also suggested to play an active role in the parenting process according to Belsky’s model. Subsequent empirical research has supported this model, consistently showing that child negative emotionality -- an intensive and frequent expression of negative emotions by the child– undermines parenting (for a meta-analysis, see Paulussen-Hoogeboom et al., 2007). Regarding the effect of child temperament on mindful parenting specifically, however, findings are more inconsistent. For example, infants’ negative emotionality has been shown to have no cross-sectional (Gartstein, 2021) or longitudinal association (Henrichs et al., 2021) with parent-reported mindful parenting, while preschool children’s “difficult” temperaments have been shown to have a negative impact on mindful parenting (Corthorn & Milicic 2016; Lo et al., 2018) as have those in school-age (aged 6–13; Moreira et al., 2021). It is, therefore, possible that child temperament interacts with child age to predict mindful parenting. To our knowledge, there is no previous research examining the association of child temperament with mindful parenting in adolescents.

Social support is one of the salient environmental factors that may directly determine parenting behaviours (Belsky, 1984), and has repeatedly been shown to increase parental warmth (Lippold et al., 2018), sensitivity (Lee et al., 2020), and involvement (Hamme Peterson et al., 2010), as well as decrease parental hostility (Lippold et al., 2018) and over-reactivity (Taraban et al., 2019). We suggest that social support may also be crucial to mindful parenting as it helps parents regulate their emotional responses to their children (Marroquin, 2011). Indeed, Bögels and Restifo (2014) state that social support is an essential theme in their mindful parenting intervention. So far, however, only one study has empirically examined the relationship between social support and parent-reported mindful parenting, finding that parents who perceived more social support also reported more mindful parenting in a sample of kindergarteners and primary schoolers (Wang & Lo, 2020). Given this promising finding, it is warranted to assess the effect of social support on mindful parenting in adolescents as well.

Indirect effects

As well as the direct effects of parenting determinants, a key theme for Belsky’s model of parenting process involves the indirect effects of these determinants via parental psychological well-being. For example, parental psychological distress is seen as a potential mechanism by which child negative emotionality affects parenting, since parenting children with high negative emotionality is more stressful than parenting children with low negative emotionality (Mulsow et al., 2002). Similarly, emotional, instrumental, and informative support provided to parents by available social networks (e.g., spouses, family, friends, or professionals) may be a key determinant of parenting, posited to be mediated by parents’ psychological well-being (Belsky, 1984). These mechanistic pathways for determinants of traditional parenting model are supported by empirical research (negative emotionality: e.g., Laukkanen et al., 2014; Xing et al., 2017; social support: e.g., Lippold et al., 2018; Östberg & Hagekull, 2000; Taylor et al., 2015), but are neglected for mindful parenting. We hypothesised similar mechanisms for mindful parenting.

Parenting in context

Updating Belsky’s framework, Taraban and Shaw (2018) emphasised the interacting impact of contextual factors (e.g., support, socioeconomic status (SES), and culture) in the parenting process, suggesting that the direct and indirect influences of determinants on parenting may differ across contexts (Bornstein et al., 2007; Taraban et al., 2019). This remains unexplored for mindful parenting.

An important contextual determinant of parenting is culture, shaping parenting behaviours (for review, see also Lansford 2022). Importantly, culture has been suggested to have a moderating role, altering the associations between determinants and parenting (Taraban & Shaw, 2018), although the research is scarce and inconclusive. For example, Japanese mothers have been shown to be more rejective than Korean mothers (Son et al., 2020), and Chinese immigrant mothers to be more non-supportive than European American mothers (Yang et al., 2020) while dealing with temperamentally “difficult” children. Similarly, school social support was related to less harsh parenting behaviours in Dominican-American but not Mexican-American parents (Serrano-Villar et al., 2017). In contrast, no cultural differences were observed in the association between child temperament and parental psychological control between Chinese and Korean immigrant mothers, with “easier” child temperament associated with less psychological control in both cultures (Cheah et al., 2016). Likewise, the association of parental well-being with parental psychological control between Chinese and Korean immigrant mothers (Cheah et al., 2016), as well as the associations of family support with positive parenting between Mexican and Dominican Americans (Serrano-Villar et al., 2017) have been shown to be comparable, implying that personal and contextual sources are determinants of parenting regardless of culture. Taken together, what little cross-cultural research there is testing Taraban and Shaw’s (2018) model on the determinants of traditional parenting model, reveals inconsistent findings.

Cross-cultural studies of mindful parenting are even more limited, considering ethnic minorities within the same country and reporting comparable correlates of mindful parenting, yet are restricted in their power to consider the question (Park et al., 2020). To our knowledge, no study has yet directly compared the mindful parenting process as moderated by culture. Addressing this gap, we tested whether culture interacts with social support, child temperament, and parental psychological distress to shape mindful parenting. Specifically, we were interested in comparing collectivist (Türkiye) and individualist (UK) cultures because these different cultural values have been considered one of the most influential factors in the parenting process (Bornstein, 2012). Due to the limited existing literature, our comparisons of determinants across cultures were exploratory only. As the concept of mindfulness itself is claimed to be universal (Kabat-Zinn, 2005), however, we expected the mindful parenting levels of parents to be similar in both cultures.

Current study

In a sample of UK and Türkiye parents and children, we examined the overall hypothesis that mindful parenting is multiply determined by parent characteristics (i.e., parents’ psychological distress), child characteristics (i.e., negative emotionality), and family social environment (i.e., social support), and that psychological distress would provide a mechanism through which determinants have influence. Specifically, we hypothesised that (1) parents’ social support would directly and indirectly predict mindful parenting through parental psychological distress, (2) child negative emotionality would directly and indirectly predict mindful parenting through parental psychological distress, and (3) culture would play a moderating role in the process of mindful parenting. Moreover, we further expand the literature by exploring the determinants of both parent- and child-reported mindful parenting. The proposed process of the mindful parenting model is given in Fig. 1.

Methods

Participants

One hundred and ten parent-child dyads completed the English questionnaires, and 174 parent-child dyads completed the Turkish version of the questionnaires. Twenty-one participants were excluded as they did not meet the eligibility criteria (not UK/Türkiye residence (n = 3/n = 2), children not between 11 and 16 years old (n = 4), self-reported mental health issue (n = 3), not living full-time with their children (n = 5) or because they failed to complete at least 80% of the questionnaires (n = 4).

Thus, the final sample composed of 101 UK parent-child dyads [90 mothers (89.1%) and 11 fathers (10.9%)) of 57 girls (56.4%), 43 boys (42.6%) (and one data missing)] and 162 Turkish parent-child dyads [151 mothers (93.2%), 11 fathers (6.8%); 87 girls (53.7%) and 75 boys (46.3%)]. The mean age of UK parents was 45.89 years (ranged 28 to 69; SD = 6.54), and of Turkish parents was 43.07 years (ranged 29 to 55; SD = 5.08). UK parents were significantly older than Türkiye parents (t = 3.917, p < .001). UK parents had between one and five children (M = 2.15; SD = 0.81), and Turkish parents had between one and eight children (M = 1.99; SD = 0.92). The mean age of the target children was 13.06 years (SD = 1.64) in the UK and 13.28 years (SD = 1.65) in Türkiye. Parents in both subsamples were well-educated (82.1% of UK parents and 67.5% of Turkish parents hold an undergraduate or higher degree). UK parents reported a mean score of 6.80 (SD = 1.77; ranged from 1 to 10) and Turkish parents 6.75 (SD = 1.66; ranged from 2 to 10) on the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status (Adler et al., 2000). There were no significant differences in child age (t = -1.046, p = .297), the number of children parents had (t = 1.447, p = .149) or perceived SES (t = 0.255, p = .779) between cultures, and samples did not differ by child sex [χ2(1) = 0.271, p = .602] or parent gender [χ2(1) = 1.365, p = .243].

Procedure

Parents were recruited through targeted online social media groups (Twitter, Instagram, Facebook) between March and July 2021 using Qualtrics Survey Software. To be eligible for the study, (1) parents had to have at least one child aged 11–16 years living with them full time, as well as (2) parents and their target children had to have no diagnoses of learning disability, (neuro)developmental or mental-health disorder, (3) had to reside in the UK or Türkiye, and (4) had to be native or fluent in English or Turkish. Parents’ consent and children’s assent were obtained. At the end of the questionnaires, participants were given debriefing information, including contact details of researchers and available mental health support organisations. The BLINDED Research Ethics Committee granted ethical approval (Protocol number BLINDED).

Measures

Demographic information

Parents reported their age (years), gender, marital status, the highest level of educational qualification, number of children, relationship with the target child, whether they lived with the child full-time, and child’s age (years) and sex. The Macarthur Scale of Subjective Social Status (Adler et al., 2000) was used to evaluate parent-perceived SES. The scale has one item for which individuals rate their perceived SES on a ladder with ten rungs scored 1 to 10; higher scores indicate higher levels of perceived SES.

Mindful parenting

Parents’ and children’s perceptions of mindful parenting were assessed using total scores of the 18-item Mindful Parenting Inventories for Parents (MPIP) and Children (MPIC; BLINDED). The MPIP/MPIC were recently translated and adapted for Turkish. Specifically, items were translated into Turkish by two independent clinical psychologists, forming the preliminary versions of the Turkish inventories. These were then independently back-translated by a Turkish clinical psychologist knowledgeable about mindfulness, and a bilingual and bicultural psychology student not knowledgeable about the subject of the scale (Van Widenfelt et al., 2005). Neither of the back-translators had seen the original English versions before translation. The final version of the Turkish MPIP/MPIC was sent to two Turkish parents and children before data collection to assess the comprehensibility of the items, before full validation of the inventories was conducted in a Turkish sample of parents and their children aged 11–16 (BLINDED).

Parents and children rated their perceptions of mindful parenting on a five-point scale from “never true” (1) to “always true” (5). Eight negative items of the MPIP/MPIC were reverse scored, such that higher scores indicate higher levels of mindful parenting. Example items include, “I quickly become defensive when my child and I argue/My mother/father quickly becomes defensive when we argue” and “I accept that my child has opinions that are different from mine/My mother/father accepts that I have opinions that are different from hers/his.” In both cultures, reliability was good (MPIP: αUK = 0.89, αTR = 0.88; MPIC αUK = 0.91, αTR = 0.89).

Parental psychological distress

Parents’ psychological distress was measured using the total scores of the 21-item version of the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond 1995; Sarıçam, 2018). Parents reported their psychological distress on a four-point scale ranging from “Did not apply to me at all” (0) to “Applied to me very much or most of the time” (3). Example items include, “I couldn’t seem to experience any positive feeling at all”, “I was aware of dryness of my mouth”, and “I found it hard to wind down.” DASS-21 had excellent internal reliability in the UK (α = 0.95) and Türkiye (α = 0.93).

Child negative emotionality

“Emotionality” Subscale of The Emotionality Activity Sociability Temperament Survey (EASTS; Buss & Plomin, 1984; Eyüpoğlu, 2006) was used to measure parent perceptions of child negative emotionality. A total of six items were rated by parents on a five-point scale ranging from “Not characteristic/typical” (1) to “Very characteristic/typical” (5) (e.g., My child reacts intensely when upset). The scale demonstrated good internal reliability in the UK (α = 0.89) and Türkiye (α = 0.79).

Social support

The total score of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Eker et al., 2001; Zimet et al., 1988) was used to evaluate parents’ perceptions of social support. Parents reported perceived social support from parents, family, friends, and specific others on a seven-point scale from “Very Strongly Disagree” (1) to “Very Strongly Agree” (7). Sample items include, “My friends really try to help me”, “I can talk about my problems with my family”, and “There is a special person in my life who cares about my feelings.” Internal reliabilities were excellent both in the UK (α = 0.96) and Türkiye (α = 0.93).

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 29.0 and AMOS 29.0. Data were missing completely at random in UK parents [χ2(175) = 196.711, p = .258], Türkiye parents [χ2(59) = 48.673, p = .829] and Türkiye children [χ2(28) = 37.068, p = .117]. There were no missing in UK children’s data. The expectation maximisation method was used to handle parents’ missing data in continuous variables (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). We investigated relationships between variables using Pearson’s correlations. Independent samples t-tests were used to assess mean level differences between the UK and Türkiye samples. We conducted multiple-group path analysis (with Emulisrel correction) to test the hypothesised process of the mindful parenting model (see Fig. 1) and the invariance of the model across cultures (Byrne, 2016). Sufficient statistical power was provided by the sample size for the analysis (i.e., 100 participants per group; Kline, 2005).

We used the Comparative Fit Index (CFI ≥ 0.90), Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA ≤ 0.08), and Standardised Root-Mean-Square Residual (SRMR ≤ 0.09) to evaluate the model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Chi-square change between unconstrained and constrained models was examined to test equivalence between UK and Türkiye models. Insignificant chi-square change between unconstrained and constrained models indicates noninvariant paths across cultures (Byrne et al., 1989; Kline, 2005). We also examined changes between the models in CFI using the cut-off criteria of − 0.005 recommended for invariance testing in small samples (Chen, 2007). In the case of cultural inequivalence, we identified variant paths that needed to be freely estimated between groups by constraining only one path to be equal at a time. Finally, we analysed direct and indirect effects using 5000 bias-corrected bootstrapped samples with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Preliminary results

Table 1 presents correlations, descriptive statistics, and group comparisons for all study variables. There were no mean differences between the UK and Türkiye samples in MPIP (t = -1.251, p = .212) or MPIC (t = 0.40, p = .688) total scores. A significant cultural mean difference between the UK and Türkiye was found only in child negative emotionality; Turkish parents reported higher child negative emotionality than UK parents (t = -5.95***, p < .001). As given in Table 1, correlations within cultures were small to moderate in effect size and in expected directions. In the UK, Pearson correlation analysis revealed that both parent and child perceptions of mindful parenting were negatively associated with child negative emotionality (r = − .38, p < .001; r = − .37, p < .001, respectively) and with parental psychological distress (r = − .34, p < .001; r = − .23, p < .001, respectively). In Türkiye, for both parent and child perceptions, mindful parenting was positively associated with parental social support (r = .23, p = .003; r = .22, p = .006, respectively) and negatively associated with parental psychological distress (r = − .39, p < .001; r = − .29, p < .001, respectively).

Note that, in the following multiple-group path analysis, we allowed covariances between the error terms of the parent- and child-report mindful parenting because their correlations were high (see Table 1). The effects of parent age and parent gender on MPIP were controlled in the model as parent age for the Türkiye sample (r = .18, p = .026) and parent sex for the UK sample (r = .21, p = .034; 1 = mother, 2 = father) were related to mindful parenting.

Multiple group path analysis

Total effect model

We tested the total effects of social support and child negative emotionality on MPIP and MPIC across cultures. The unconstrained model showed good fit to the data [χ2(4) = 6.323, χ2/df = 1.581, CFI = 0.984, RMSEA = 0.047, SRMR = 0.044]. We then constrained all paths in the model to be equal across groups (i.e. cultures). Compared to the unconstrained model, the constrained model fit was worse in the constrained model [χ2(10) = 16.726, χ2/df = 1.673, CFI = 0.953, RMSEA = 0.051, SRMR = 0.072; ∆χ2(6) = 10.403, p = .109, ∆CFI = − 0.031]. Although the chi-square change was insignificant, as CFI significantly reduced in the constrained model, we concluded that not all paths should be treated as equal. We found that the paths from child negative emotionality to both MPIP and MPIC were variant across cultures, as such, freely estimated those variant paths across groups [χ2(8) = 9.311, χ2/df = 1.164, CFI = 0.991, RMSEA = 0.025, SRMR = 0.058; ∆χ2(4) = 2.989, p = .560, ∆CFI = 0.007]. According to the results, the paths between social support and MPIP (b = 0.06, p = .014) and MPIC (b = 0.08, p = .009) were significant both in the UK and Türkiye. However, the path between child negative emotionality and MPIP (bUK = − 0.17, p < .001; bTR = − 0.04, p = .391) and MPIC (bUK = − 0.26, p < .001; bTR = − 0.02, p = .765) were significant in the UK only.

Direct and indirect effect model

The unconstrained multiple group mediation path model in which social support and child negative emotionality predicted MPIP and MPIC through parental psychological distress had a good model fit to the data [χ2(8) = 15.372, χ2/df = 1.922, CFI = 0.968, RMSEA = 0.060, SRMR = 0.058)]. We then constrained paths in the model to be equal across groups. Compared to the unconstrained model, the constrained model fit was worse in the constrained model [χ2(18) = 29.379, χ2/df = 1.632, CFI = 0.951, RMSEA = 0.049, SRMR = 0.088); ∆χ2(10) = 14.007, p = .173, ∆CFI = − 0.017]. Although the chi-square change was insignificant, as CFI significantly reduced in the constrained model, we concluded that not all paths should be treated as equal. Again, we found that the paths from child negative emotionality to both MPIP and MPIC were variant across cultures; as such, we freely estimated those variant paths across groups for the subsequent analysis [χ2(16) = 23.481, χ2/df = 1.468, CFI = 0.968, RMSEA = 0.042, SRMR = 0.078; ∆χ2(8) = 8.109, p = .423, ∆CFI = 0.000]. Finally, we constrained the covariance between MPIP and MPIC to be equal across groups. The cross-reporter association of mindful parenting was invariant between the UK and Türkiye [χ2(17) = 24.079, χ2/df = 1.416, CFI = 0.970, RMSEA = 0.040, SRMR = 0.077; ∆χ2(1) = 0.589, p = .440, ∆CFI = 0.002].

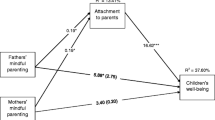

As given in Table 2, social support was not directly associated with parent-reported (b = 0.01, p = .607) or child-reported mindful parenting (b = 0.04, p = .201) in either the UK or Türkiye (see also Fig. 2). However, social support indirectly predicted MPIP (ab = 0.04, p < .000) and MPIC (ab = 0.04, p = .002) through parental psychological distress in both cultures. In the UK only, child negative emotionality directly predicted MPIP (bUK = − 0.12, p = .012; bTR = − 0.02, p = .642) and MPIC (bUK = − 0.22, p = .001; bTR = 0.00, p = .988). Yet, it indirectly predicted MPIP (ab = − 0.03, p = .001) and MPIC (ab = − 0.03, p = .002) through parental psychological distress in both cultures.

Unstandardized path coefficients obtained in hypothesised multiple-group path analysis. Note. All paths were constrained to be equal across the UK and Türkiye except for the thick lines, which were significant for the UK samples only (left). Dashed lines represent insignificant regression weights. DASS = Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, MPIP = Mindful Parenting Inventory for Parents, MPIC = Mindful Parenting Inventory for Children.

Discussion

The current study aimed to explore the determinants of mindful parenting in the UK Türkiye, basing our expectations on Belsky’s (1984) model. We tested total as well as direct and indirect associations of parent characteristics (psychological distress), child characteristics (negative emotionality), and family social environment (parental perceived social support) with mindful parenting in UK- and Türkiye-based parents and their children aged 11–16 years. In addition, this study also aimed to identify culture-general and culture-specific aspects of these associations grounded in Taraban and Shaw’s (2018) model. Furthermore, we expanded on previous mindful parenting research by using multiple informants of mindful parenting (i.g., parents and their children). Overall, our study showed that both parent and child perspectives of mindful parenting are multiply determined. The associations of child negative emotionality and social support with both perspectives on mindful parenting were mediated by parental psychological distress. However, culture had a moderating role in this process. As discussed below, child negative emotionality was not a direct determinant of mindful parenting in Türkiye, although otherwise, the processes did not differ across countries.

First, in line with but going beyond earlier studies comparing ethnic minorities within the same country (e.g., “white people” and “people of colour”; Parent et al., 2016a, b; Park et al., 2020), we found no significant differences in parent-reported mindful parenting between the UK and Türkiye. Further, for the first time, our study suggests that child reports mirror this finding, further supporting the idea that mindful parenting is a “culture-free” skill (McCaffrey et al., 2017). Moreover, although counter to previous research comparing the UK and Türkiye (Aytac & Pike, 2018; Kortantamer, 2011), there were no significant cultural differences in parent-reported perceived social support or psychological distress in our sample. This may be because our samples from the two countries were similar in sociodemographics. However, parents in Türkiye reported higher levels of child negative emotionality than parents in the UK. This finding is consistent with previous research, where children in less individualistic countries (e.g., Türkiye) reported higher levels of negative affectivity than their counterparts in more individualistic countries (e.g., Finland; Slobodskaya et al., 2019). This might be because children’s expression of emotions is considered more normative in more individualistic cultures (Cho et al., 2022; Friedlmeier et al., 2011), resulting in British parents reporting less negative emotionality in their children compared to their Turkish parents (Aytac et al., 2019).

Second, our results showed that while the total, direct and indirect effects of child negative emotionality on MPIP and MPIC were significant in the UK, only its indirect effect was significant in Türkiye. That is, the culture did not moderate the indirect effect of children’s negative impact on mindful parenting. As hypothesised and in line with previous findings (Laukkanen et al., 2014; Xing et al., 2017), increased child temperamental difficulty predicted higher levels of psychological distress in parents, which in turn resulted in less mindful parenting in both cultures. However, perhaps more interestingly, child negative emotionality directly determined mindful parenting in the UK but not in Türkiye despite the higher negative emotionality of Turkish children reported by parents. This finding is somewhat consistent with recent research showing that child temperament did not predict abusive parenting and only weakly predicted coercive parenting in Turkish mothers (Gölcük & Kazak-Berument, 2021). Given that certain temperament tendencies of children are considered “tolerable” in some cultures while “difficult” in others (Harkness & Super, 1996; Son et al., 2020), the explanation can be that, compared to Türkiye parents, UK parents were assumably more sensitive to children’s temperament. Thus, children’s negative affect impaired UK parents’ mindful parenting over and above its effect via parental well-being.

However, these findings contradict the common view that parents in more individualistic cultures respond more supportive and less unsupportive to children’s expression of (negative) emotions (Cho et al., 2022; Friedlmeier et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2020). This may reflect the cross-cultural difference unique to mindful parenting beyond traditional models of parenting. Indeed, we know from previous research that Turkish parents may display more “mindful” attitudes towards the expression of negative emotions than European parents, e.g., “it is okay to feel angry” (Corapci et al., 2018, p. 273). Therefore, although Turkish parents reported more child negative emotionality, they might be able to stay mindful in the face of the expression of these emotions. Further research is needed to explore the culture-specific link between child temperament and mindful parenting.

Third, social support was correlated with MPIP and MPIC in Türkiye but not in the UK. Yet, the multiple-group path model showed that these differences were negligible. Accordingly, the total effects of social support on MPIP and MPIC were significant in both cultures. This result is in line with earlier studies showing that parents who perceive more social support showed more mindful (Wang & Lo, 2020) and positive parenting but less negative parenting (Lippold et al., 2018; Taraban et al., 2019), as well as that this relationship is similar across cultures (Serrano-Villar et al., 2017). Moreover, in both cultures, parental psychological distress fully mediated the associations between parents’ social support and MPIP and MPIC. Namely, social support did not directly predict parent- or child-report mindful parenting after accounting for parental well-being; it only indirectly affected mindful parenting by first reducing parental psychological distress. These results fit well with Belsky’s (1984) argument that the direct effect of social support on parenting is not as strong as its indirect effect through parental psychological well-being.

Taken together, our results show that mindful parenting is multiply determined by parent characteristics, child characteristics, and family social environment regardless of the reporter. Moreover, this process is somewhat similar across cultures. Our results also partially support Belsky’s (1984) claim that these determinants do not have an equal influence on parenting. To be specific, ‘parental psychological distress is a better determinant of mindful parenting than social support, which itself is a stronger determinant than child negative emotionality’ (Belsky, 1984; p. 63); the former was supported in both cultures, while the latter was supported only in Türkiye, as discussed above.

Limitations and future directions

As previously stated, despite the increasing research on mindful parenting, cross-cultural differences and child perceptions of mindful parenting have been understudied. This study is the first to directly compare the mindful parenting process in two cultures using dyadic parent-child data. Yet, first, our findings may be somewhat limited by the samples consisting predominantly of mothers and their typically developed children aged 11–16 years. As such, further work is needed to generalise the findings to different types of families. Note that we invited both mothers and fathers; therefore, such homogeneity of our samples as in previous studies (e.g., Kim et al., 2019; Lo et al., 2018; Moreira et al., 2018) may reflect that mothers are still primary caregivers of children. It seems that fathers need to be specifically targeted to better explore the mindful parenting process in fathers.

Second, self-report scales of parenting may cause biased results. Parents, especially from relatively more collectivist cultures such as Türkiye, may tend to self-report socially desirable parenting behaviours (Bernardi, 2006; Bornstein et al., 2015). Although our study increases the validity of the measurement using both parent and child reports, studies considering observational scales (e.g., Mindful Parenting Observational Scales; Geier et al., 2012) are warranted to capture a full picture of mindful parenting (Morsbach & Prinz, 2006).

Third, this study did not examine potentially confounding influences at the societal level, such as parenting beliefs and values or religion. These would be useful additions for, future studies so as to understand the origins of cross-cultural similarities and differences in the determinants of mindful parenting.

Fourth, we cannot establish causality due to the cross-sectional nature of our data. For example, the association between child temperament and mindful parenting has been suggested to be bidirectional, such that mindful parenting may decrease negative emotionality in children, and in turn, child negative emotionality may augment mindful parenting (Lengua & Kovacs, 2005). Child temperament and parental psychological well-being have also been shown to affect each other bidirectionally; as such, increased parental distress might be the risk factor for child negative emotionality (Wiggins et al., 2014). Moreover, the mindful parenting model has proposed that parental well-being is an outcome, rather than a predictor, of mindful parenting (Anand et al., 2021; Duncan et al., 2009). We encourage future research to use genetically informed (e.g., Oliver, 2015) and/or cross-lagged panel designs (Kenny, 2005) to explore directionality.

Implications

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study has valuable implications for mindful parenting research and practice. For example, considering the multiple risk factors for low mindful parenting, it may be best practice for non-clinical mindful parenting interventions to target especially high-risk parents, such as those with low social support and psychological well-being, as well as those with “difficult” children (Cowling & Van Gordon, 2022).

Using the multiple-group approach, moreover, we revealed culture-specific and culture-generic determinants of parenting. Here, our results imply that parental psychological well-being is perhaps the most critical determinant in the process of mindful parenting, showing its mediating role in the link from child temperament and social support to parents’ and children’s perceptions of mindful parenting parental both in the UK and Türkiye. Therefore, we suggest that preventive and therapeutic mindful parenting interventions for non-clinical samples (Potharst et al., 2021) may essentially focus on parents’ psychological well-being.

However, we also showed that parental vulnerability to child negative emotionality might vary across cultures, endorsing the importance of using cross-cultural mindful parenting research. We thus hope our results may encourage further cross-cultural research to reveal differences/similarities in the determinants of mindful parenting. Thereby, interventions in a given culture can be revised for parents with a lower likelihood of adopting mindful parenting rather than relying solely on mindful parenting models (Kil & Antonacci, 2020) and interventions derived from mostly western families (Anand et al., 2021).

Data availability

The data sets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Adler, N. E., Epel, E. S., Castellazzo, G., & Ickovics, J. R. (2000). Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: preliminary data in healthy, white women. Health Psychology, 19(6), 586–592. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.19.6.586

Anand, L., Sadowski, I., Per, M., & Khoury, B. (2021). Mindful parenting: a meta-analytic review of intrapersonal and interpersonal parental outcomes. Current Psychology, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02111-w

Aytac, B., & Pike, A. (2018). The mother-child relationship and children’s behaviours: a multilevel analysis in two countries. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 49(1), 45–71. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.49.1.45

Aytac, B., Pike, A., & Bond, R. (2019). Parenting and child adjustment: a comparison of turkish and english families. Journal of Family Studies, 25(3), 267–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2016.1248855

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

Baumrind, D. (1966). Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Development, 37(4), 887–907. https://doi.org/10.2307/1126611

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: a process model. Child Development, 55(1), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129836

Bernardi, R. A. (2006). Associations between Hofstede’s cultural constructs and social desirability response bias. Journal of Business Ethics, 65(1), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-005-5353-0

Bögels, S. M., Hellemans, J., van Deursen, S., Römer, M., & van der Meulen, R. (2014). Mindful parenting in mental health care: Effects on parental and child psychopathology, parental stress, parenting, coparenting, and marital functioning. Mindfulness, 5(5), 536–551. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0209-7

Bögels, S., & Restifo, K. (2014). Mindful parenting: a guide for mental health practitioners. W. W. Norton & Company.

Bornstein, M. H. (2012). Cultural approaches to parenting. Parenting: Science and Practice, 12(2–3), 212–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2012.683359

Bornstein, M. H., Hahn, C. S., Haynes, O. M., Belsky, J., Azuma, H., Kwak, K., Maital, S., Painter, K. M., Varron, C., Pascual, L., Toda, S., Venuti, P., Vyt, A., & de Galperín, C. Z. (2007). Maternal personality and parenting cognitions in cross-cultural perspective. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 31(3), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025407074632

Bornstein, M. H., Putnick, D. L., Lansford, J. E., Pastorelli, C., Skinner, A. T., Sorbring, E., Tapanya, S., Uribe Tirado, L. M., Zelli, A., Alampay, L. P., Al-Hassan, S. M., Bacchini, D., Bombi, A. S., Chang, L., Deater-Deckard, K., Di Giunta, L., Dodge, K. A., Malone, P. S., & Oburu, P. (2015). Mother and father socially desirable responding in nine countries: two kinds of agreement and relations to parenting self-reports. International Journal of Psychology, 50(3), 174–185. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12084

Boyce, W. T., Frank, E., Jensen, P. S., Kessler, R. C., Nelson, C. A., & Steinberg, L. (1998). Social context in developmental psychopathology: recommendations for future research from the MacArthur Network on psychopathology and development. Development and Psychopathology, 10(2), 143–164. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579498001552

Burk, W. J., & Laursen, B. (2010). Mother and adolescent reports of associations between child behavior problems and mother-child relationship qualities: separating shared variance from individual variance. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(5), 657–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9396-z

Buss, A., & Plomin, R. (1984). Temperament: early developing personality traits. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Byrne, B. M., Shavelson, R. J., & Muthén, B. (1989). Testing for the equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures: the issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychological Bulletin, 105(3), 456–466. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.105.3.456

Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with amos: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315757421

Cheah, C. S., Yu, J., Hart, C. H., Özdemir, S. B., Sun, S., Zhou, N., Olsen, J. A., & Sunohara, M. (2016). Parenting hassles mediate predictors of chinese and korean immigrants’ psychologically controlling parenting. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 47, 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2016.09.005

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(3), 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

Cheung, K., & Theule, J. (2019). Paternal depressive symptoms and parenting behaviors: an updated meta-analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(3), 613–626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-01316-1

Cheung, R. Y., Cheng, W. Y., Li, J. B., Lam, C. B., & Chung, K. K. H. (2021). Parents’ depressive symptoms and child adjustment: the mediating role of mindful parenting and children’s self-regulation. Mindfulness, 12(11), 2729–2742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-021-01735-0

Cho, S. I., Song, J. H., Trommsdorff, G., Cole, P. M., Niraula, S., & Park, S. Y. (2022). Mothers’ reactions to children’s emotion expressions in different cultural contexts: comparisons across Nepal, Korea, and Germany. Early Education and Development, 33(5), 858–876. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2022.2035178

Corapci, F., Friedlmeier, W., Benga, O., Strauss, C., Pitica, I., & Susa, G. (2018). Cultural socialisation of toddlers in emotionally charged situations. Social Development, 27(2), 262–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12272

Corthorn, C., & Milicic, N. (2016). Mindfulness and parenting: a correlational study of non-meditating mothers of preschool children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(5), 1672–1683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0319-z

Cowling, C., & Van Gordon, W. (2022). Mindful parenting: future directions and challenges. International Journal of Spa and Wellness, 5(1), 50–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/24721735.2021.1961114

Coyne, L. W., Low, C. M., Miller, A. L., Seifer, R., & Dickstein, S. (2007). Mothers’ empathic understanding of their toddlers: Associations with maternal depression and sensitivity. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16(4), 483–497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-006-9099-9

Danese, A., & Widom, C. S. (2020). Objective and subjective experiences of child maltreatment and their relationships with psychopathology. Nature Human Behaviour, 4, 811–818. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0880-3

de Bruin, E. I., Zijlstra, B. J., Geurtzen, N., van Zundert, R. M., van de Weijer-Bergsma, E., Hartman, E. E., Nieuwesteeg, A. M., Duncan, L. G., & Bögels, S. M. (2014). Mindful parenting assessed further: psychometric properties of the dutch version of the interpersonal mindfulness in parenting scale (IM-P). Mindfulness, 5(2), 200–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0168-4

Duncan, L. G., Coatsworth, J. D., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). A model of mindful parenting: implications for parent–child relationships and prevention research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12(3), 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-009-0046-3

Eker, D., Arkar, H., & Yaldiz, H. (2001). Çok Boyutlu Algılanan Sosyal Destek Ölçeği’nin gözden geçirilmiş formunun faktör yapısı, geçerlik ve güvenirliği [Factorial structure, validity and reliability of the revised form of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support]. Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi, 12(1), 17–25.

Emerson, L. M., Aktar, E., de Bruin, E., Potharst, E., & Bögels, S. (2021). Mindful parenting in secondary child mental health: key parenting predictors of treatment effects. Mindfulness, 12(2), 532–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01176-w

Eyüpoğlu, H. (2006). The relationships between parental emotion expressivity, children’s temperament and children’s coping strategy [Master’s Thesis, Middle East Technical University]. OpenMETU. http://etd.lib.metu.edu.tr/upload/12608240/index.pdf. Accessed 18 December 2022.

Fernandes, D. V., Canavarro, M. C., & Moreira, H. (2021). The mediating role of parenting stress in the relationship between anxious and depressive symptomatology, mothers’ perception of infant temperament, and mindful parenting during the postpartum period. Mindfulness, 12(2), 275–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01327-4

Friedlmeier, W., Corapci, F., & Cole, P. M. (2011). Emotion socialisation in cross-cultural perspective. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(7), 410–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00362.x

Gartstein, M. A. (2021). Development and validation of the mindful parenting in Infancy Scale (MPIS). Infancy: the official journal of the International Society on Infant Studies, 26(5), 705–723. https://doi.org/10.1111/infa.12417

Geier, M. H., Coatsworth, J. D., Turksma, C., & Greenberg, M. T. (2012). The mindful parenting rating scales Coding Manual. The Strengthening Families in Pennsylvania Project, Department of Health and Human Development, The Pennsylvania State University.

Gerdes, A. C., Hoza, B., & Pelham, W. E. (2003). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disordered boys’ relationships with their mothers and fathers: child, mother, and father perceptions. Development and Psychopathology, 15(2), 363–382. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579403000208

Gerdes, A. C., Hoza, B., Arnold, L. E., Hinshaw, S. P., Wells, K. C., Hechtman, L., Greenhill, L. L., Swanson, J. M., Pelham, W. E., & Wigal, T. (2007). Child and parent predictors of perceptions of parent-child relationship quality. Journal of Attention Disorders, 11(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054706295664

Geurtzen, N., Scholte, R. H., Engels, R. C., Tak, Y. R., & van Zundert, R. M. (2015). Association between mindful parenting and adolescents’ internalising problems: non-judgmental acceptance of parenting as core element. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(4), 1117–1128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-9920-9

Gölcük, M., & Berument, S. K. (2021). The relationship between negative parenting and child and maternal temperament. Current Psychology, 40(7), 3596–3608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00307-9

Goodman, S. H., Simon, H. F. M., Shamblaw, A. L., & Kim, C. Y. (2020). Parenting as a mediator of associations between depression in mothers and children’s functioning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 23(4), 427–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-020-00322-4

Hamme Peterson, C., Buser, T. J., & Westburg, N. G. (2010). Effects of familial attachment, social support, involvement, and self-esteem on youth substance use and sexual risk taking. The Family Journal, 18(4), 369–376. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480710380546

Harkness, S., & Super, C. M. (Eds.). (1996). Parents’ cultural belief systems: their origins, expressions, and consequences. Guilford Press.

Henrichs, J., van den Heuvel, M. I., Witteveen, A. B., Wilschut, J., & Van den Bergh, B. R. (2021). Does mindful parenting mediate the association between maternal anxiety during pregnancy and child behavioral/emotional problems? Mindfulness, 12(2), 370–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01115-9

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2005). Coming to our senses: healing ourselves and the world through mindfulness. Hachette UK.

Kabat-Zinn, M., & Kabat-Zinn, J. (1997). Everyday blessings: the inner work of mindful parenting. Hyperion.

Kenny, D. A. (2005). Cross-lagged panel design. https://doi.org/10.1002/0470013192.bsa156

Kerns, C. E., Pincus, D. B., McLaughlin, K. A., & Comer, J. S. (2017). Maternal emotion regulation during child distress, child anxiety accommodation, and links between maternal and child anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 50, 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.05.002

Kil, H., & Antonacci, R. (2020). Mindful parenting programs in non-clinical contexts: a qualitative review of child outcomes and programs, and recommendations for future research. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(7), 1887–1898. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01714-4

Kim, E., Krägeloh, C. U., Medvedev, O. N., Duncan, L. G., & Singh, N. N. (2019). Interpersonal mindfulness in parenting scale: testing the psychometric properties of a korean version. Mindfulness, 10(3), 516–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0993-1

Kline, T. J. B. (2005). Psychological testing: a practical approach to design and evaluation. Sage Publications, Inc.

Kortantamer, Z. I. (2011). A cross-cultural study of the coping strategies of Turkish and English adults [Doctoral dissertation, Nottingham Trent University]. IRep. https://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/291. Accessed 18 December 2022.

Lansford, J. E. (2022). Annual Research Review: cross-cultural similarities and differences in parenting. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 63(4), 466–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13539

Laukkanen, J., Ojansuu, U., Tolvanen, A., Alatupa, S., & Aunola, K. (2014). Child’s difficult temperament and mothers’ parenting styles. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(2), 312–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9747-9

Lee, H. Y., Edwards, R. C., & Hans, S. L. (2020). Young first-time mothers’ parenting of infants: the role of depression and social support. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 24(5), 575–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-019-02849-7

Lengua, L. J., & Kovacs, E. A. (2005). Bidirectional associations between temperament and parenting and the prediction of adjustment problems in middle childhood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 26(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2004.10.001

Lippold, M. A., Glatz, T., Fosco, G. M., & Feinberg, M. E. (2018). Parental perceived control and social support: linkages to change in parenting behaviors during early adolescence. Family Process, 57(2), 432–447. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12283

Liu, Z., Sun, X., Guo, Y., & Yang, S. (2021). Mindful parenting is positively associated with adolescents’ life satisfaction: the mediating role of adolescents’ coping self-efficacy. Current Psychology, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01363-w

Lo, H. H. M., Yeung, J. W. K., Duncan, L. G., Ma, Y., Siu, A. F. Y., Chan, S. K. C., Choi, C. W., Szeto, M. P., Chow, K. K. W., & Ng, S. M. (2018). Validating of the interpersonal mindfulness in parenting scale in Hong Kong Chinese. Mindfulness, 9(5), 1390–1401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0879-7

Lovejoy, M. C., Graczyk, P. A., O’Hare, E., & Neuman, G. (2000). Maternal depression and parenting behavior: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(5), 561–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

Marroquín, B. (2011). Interpersonal emotion regulation as a mechanism of social support in depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(8), 1276–1290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.09.005

McCaffrey, S., Reitman, D., & Black, R. (2017). Mindfulness in Parenting Questionnaire (MIPQ): development and validation of a measure of mindful parenting. Mindfulness, 8(1), 232–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0596-7

Meppelink, R., de Bruin, E. I., Wanders-Mulder, F. H., Vennik, C. J., & Bögels, S. M. (2016). Mindful parenting training in child psychiatric settings: heightened parental mindfulness reduces parents’ and children’s psychopathology. Mindfulness, 7(3), 680–689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0504-1

Moreira, H., Caiado, B., & Canavarro, M. C. (2021). Is mindful parenting a mechanism that links parents’ and children’s tendency to experience negative affect to overprotective and supportive behaviors? Mindfulness, 12(2), 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01468-6

Moreira, H., Gouveia, M. J., & Canavarro, M. C. (2018). Is mindful parenting associated with adolescents’ well-being in early and middle/late adolescence? The mediating role of adolescents’ attachment representations, self-compassion and mindfulness. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(8), 1771–1788. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0808-7

Morsbach, S. K., & Prinz, R. J. (2006). Understanding and improving the validity of self-report of parenting. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 9(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-006-0001-5

Mulsow, M., Caldera, Y. M., Pursley, M., Reifman, A., & Huston, A. C. (2002). Multilevel factors influencing maternal stress during the first three years. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(4), 944–956. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00944.x

Oliver, B. R. (2015). Unpacking externalising problems: negative parenting associations for conduct problems and irritability. BJPsych Open, 1(1), 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjpo.bp.115.000125

Ostberg, M., & Hagekull, B. (2000). A structural modeling approach to the understanding of parenting stress. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29(4), 615–625. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP2904_13

Pan, J., Liang, Y., Zhou, H., & Wang, Y. (2019). Mindful parenting assessed in Mainland China: psychometric properties of the chinese version of the interpersonal mindfulness in parenting scale. Mindfulness, 10(8), 1629–1641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01122-w

Parent, J., & Forehand, R. (2017). The Multidimensional Assessment of Parenting Scale (MAPS): Development and Psychometric Properties. Journal of child and family studies, 26(8), 2136–2151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0741-5

Parent, J., McKee, L. G., Anton, M., Gonzalez, M., Jones, D. J., & Forehand, R. (2016a). Mindfulness in parenting and coparenting. Mindfulness, 7(2), 504–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0485-5

Parent, J., McKee, L. G., Rough, N., & Forehand, R. (2016b). The association of parent mindfulness with parenting and youth psychopathology across three developmental stages. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(1), 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-9978-x

Park, Y. R., Nix, R. L., Duncan, L. G., Coatsworth, J. D., & Greenberg, M. T. (2020). Unfolding relations among mindful parenting, recurrent conflict, and adolescents’ externalising and internalising problems. Family Process, 59(4), 1690–1705. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12498

Paulussen-Hoogeboom, M. C., Stams, G. J. J. M., Hermanns, J. M. A., & Peetsma, T. T. D. (2007). Child negative emotionality and parenting from infancy to preschool: a meta-analytic review. Developmental Psychology, 43(2), 438–453. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.438

Potharst, E. S., Baartmans, J. M. D., & Bögels, S. M. (2021). Mindful parenting training in a clinical versus non-clinical setting: an explorative study. Mindfulness, 12(2), 504–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-1021-1

Potharst, E. S., Boekhorst, M. G. B. M., Cuijlits, I., van Broekhoven, K. E. M., Jacobs, A., Spek, V., Nyklíček, I., Bögels, S. M., & Pop, V. J. M. (2019). A randomised control trial evaluating an online mindful parenting training for mothers with elevated parental stress. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, Article 1550. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01550

Sarıçam, H. (2018). The psychometric properties of turkish version of depression anxiety stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) in health control and clinical samples. Journal of Cognitive-Behavioral Psychotherapy and Research, 7(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.5455/JCBPR.274847

Schaefer, E. S. (1965). Children’s reports of parental behavior: an inventory. Child Development, 36(2), 413–424. https://doi.org/10.2307/1126465

Schofield, T. J., Parke, R. D., Coltrane, S., & Weaver, J. M. (2016). Optimal assessment of parenting, or how I learned to stop worrying and love reporter disagreement. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(5), 614–624. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000206

Serrano-Villar, M., Huang, K. Y., & Calzada, E. J. (2017). Social support, parenting, and social emotional development in young Mexican and Dominican American children. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 48(4), 597–609. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-016-0685-9

Slobodskaya, H., Kozlova, E., Han, S. Y., Garrstein, M. A., & Putham, S. P. (2019). Cross-cultural differences in temperament. In M. A. Gartstein, & S. P. Putnam (Eds.), Toddlers, parents, and culture: findings from the joint effort toddler temperament Consortium (pp. 29–39). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315203713

Son, H., Lee, Y. A., Ahn, D. H., Doan, S. N., Ha, E. H., & Choi, Y. S. (2020). Antecedents of maternal rejection across cultures: an examination of child characteristics. Sage Open, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020927040

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education.

Taraban, L., & Shaw, D. S. (2018). Parenting in context: revisiting Belsky’s classic process of parenting model in early childhood. Developmental Review, 48, 55–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2018.03.006

Taraban, L., Shaw, D. S., Leve, L. D., Natsuaki, M. N., Ganiban, J. M., Reiss, D., & Neiderhiser, J. M. (2019). Parental depression, overreactive parenting, and early childhood externalising problems: moderation by social support. Child Development, 90(4), e468–e485. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13027

Taylor, Z. E., Conger, R. D., Robins, R. W., & Widaman, K. F. (2015). Parenting practices and perceived social support: longitudinal relations with the social competence of mexican-origin children. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 3(4), 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000038

van Widenfelt, B. M., Treffers, P. D., de Beurs, E., Siebelink, B. M., & Koudijs, E. (2005). Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of assessment instruments used in psychological research with children and families. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 8(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-005-4752-1

Wang, S. S. C., & Lo, H. H. M. (2020). The role of mindful parenting in the relationship of parent and child mental health in Taiwan Chinese. China Journal of Social Work, 13(3), 232–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/17525098.2020.1815351

Wiggins, J. L., Mitchell, C., Stringaris, A., & Leibenluft, E. (2014). Developmental trajectories of irritability and bidirectional associations with maternal depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 53(11), 1191-1205e12054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.08.005

Wong, K., Hicks, L. M., Seuntjens, T. G., Trentacosta, C. J., Hendriksen, T. H. G., Zeelenberg, M., & van den Heuvel, M. I. (2019). The role of mindful parenting in individual and social decision-making in children. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 550. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00550

Xing, X., Zhang, H., Shao, S., & Wang, M. (2017). Child negative emotionality and parental harsh discipline in chinese preschoolers: the different mediating roles of maternal and paternal anxiety. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 339. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00339

Yang, Y., Song, Q., Doan, S. N., & Wang, Q. (2020). Maternal reactions to children’s negative emotions: relations to children’s socio-emotional development among european american and chinese immigrant children. Transcultural Psychiatry, 57(3), 408–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461520905997

Zhou, Z., Li, M., Wu, J., & Li, X. (2021). Differential associations between parents’ versus children’s perceptions of parental socialization goals and chinese adolescent depressive symptoms. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 681940. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.681940

Acknowledgements

The first author was awarded a fellowship from the Ministry of Turkish Education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed to the study conception and design. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Pinar Acet and both authors finalised subsequent versions of the manuscript. Both authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The UCL Research Ethics Committee granted ethical approval. The protocol number is Z6364106/2021/01/43 social research. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Informed parent consent and child assent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Acet, P., Oliver, B.R. Determinants of mindful parenting: a cross-cultural examination of parent and child reports. Curr Psychol 43, 562–574 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04327-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04327-4