Abstract

Although previous studies found the importance of community subjective social status for adolescent health, its relationship with mental health problems among refugee adolescents is unclear. To close this gap, we examined the nature of the relationship between subjective social status and externalizing problems in refugee adolescents. We carried out a cross-sectional study among three hundred and six 11–18-year-old Syrian refugee adolescents in Turkey. The measurements of the study were the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), the Depression Self Rating Scale for Children (DSRS-C), and the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS). The results supported the idea that adolescent’s community subjective social status may affect internalizing problems directly and externalizing problems indirectly via internalizing problems. The mediation effect of the internalizing problems on the relationship between subjective social status and externalizing problems were confirmed by three separate mediation models. The results were discussed in terms of previous literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

People tend to compare their social and/or economic positions with the positions of others within their various communities such as their workplace, neighborhood, or school. Apart from their objective status, they may also derive a subjective sense of place from their comparisons (i.e., subjective social status) (Adler & Stewart, 2007; Davis, 1956). The way people perceive their social status within their community was found to be related to physical and mental health problems, showing that low subjective status is positively related to increasing levels of physical and mental health problems (for a meta-analysis see Zell et al., 2018). For example, low levels of community subjective social status were found to be related to increasing depression (Cundiff et al., 2011, 2013; Fleuriet & Sunil, 2018), anxiety (Leu et al., 2008; Reitzel et al., 2017), affective dysfunction (Leu et al., 2008), perceived stress (Fleuriet & Sunil, 2018), negative physical health perception (Garza et al., 2017), back pain in older age (Mu et al., 2021), and decreasing health-related quality of life (Garey et al., 2016).

Although adolescence is a key period for the development of subjective social status and it starts to stabilize in these years of life (Goodman et al., 2015), there is a lack of research on the association between community subjective social status and mental health problems among adolescents. Some of the studies on this topic showed that decreasing community subjective social status is associated with increasing depression (Goodman et. al., 2001; Lemeshow et al., 2008), obesity (Goodman et. al., 2001), the likelihood of smoking, and drinking behaviors (Finkelstein et al., 2006; Ritterman et al., 2009; Sweeting & Hunt, 2015), and physical symptoms, psychological distress, and anger (Sweeting & Hunt, 2014). To our knowledge, there is only one study that has examined the relationship between subjective social status and mental health problems among adolescents who have refugee backgrounds (Correa-Velez et al., 2010).

Along with the pre-migration (e.g. war/poverty in the country of origin) and the migration experiences (e.g. the loss of family/friends, migration related traumatic experiences), the post-migration experiences are also considered to be responsible for the high prevalence of mental health problems among refugee adolescents (Lurie & Nakash, 2015). Previous theoretical frameworks usually define the detrimental post-migration experiences of youths within two contexts: (a) the larger societal context (e.g., acculturation problems, perceived discrimination, language barriers neglected healthcare and education, objective socioeconomic status) (e.g., Ellis et al., 2008; Murad, et al., 2003), and (b) familial context (being unaccompanied, gender-related family issues) (e.g., Chan et al., 2009). However, a third context, their own communities (e.g., their own schools, religious groups, and other closed groups they socialize) are generally ignored.

Objectives

The current study aims to contribute to close this gap by examining the role of a community-related factor, namely community subjective social status, on the mental health problems of refugee adolescents. We specifically focused on the nature of the association between community subjective social status and externalizing problems. Externalizing behaviors are mainly characterized by actions such as hostility, aggression, and antisocial behavior, whereas internalizing behaviors are characterized primarily by processes within the self, such as anxiety, depression, and somatization (see Achenbach et al., 2016 for a detailed review). We argue that internalizing problem behaviors would mediate the relationship between community subjective social status and externalizing problems because majority of the previous studies shows the essentialness of internalizing problem behaviors in externalizing problem behaviors. There are two distinct theoretical approaches to internalizing/externalizing problems (see Stone et al., 2015). The early bidirectional model of problem behaviors argue that internalizing (including depression, anxiety, withdrawal, and eating disorders) and externalizing problems (including aggression, oppositional disorders, delinquency, and school problems) tend to co-occur (Achenbach, 1991). However, the directional model claim that internalizing problems precede externalizing problems (e.g., Bittner et al., 2007; Ritakallio et al., 2008; Vitaro et al., 2000) and emphasized the importance of internalizing problems on externalizing problems. For example, in a two-year prospective follow-up study Ritakallio et al (2008) found that externalizing behaviors do not predict internalizing behaviors but internalizing behaviors predict external behaviors. Because the results of the previous studies that favor directional model perspective are relatively clearer, we followed this approach in the current study. Thus, in line with this perspective we tested the hypothesis that internalizing problems would mediate the relationship between subjective social status and externalizing problems.

Methods

Participants

A total of 306 11–18-year-old Syrian refugee adolescents (Mage = 14.40; SD = 1.84) attending an NGO governed school (sixth to twelfth grade) in Istanbul; 159 females (%52) and 147 males (%48). The mean household population of the participants was 5.52 (SD = 5.52).

Measurements

MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status

It is a broadly used instrument to measure subjective social status in the local community measured by a symbolic ladder with 10 rungs (1 = lowest status to 10 = highest status) (Adler et al., 2000; Goodman et. al., 2001). Along with providing a picture of a ladder, participants were asked to: “Think of this ladder as showing where people stand in their communities. At the top of the ladder are the people who have the highest standing in their community. At the bottom are the people who have the lowest standing in their community. For example, you can think about your school. At the top of the ladder are the people in your school with the most respect, the highest grades, and the highest standing. At the bottom are the people whom no one respects, no one wants to hang around with, and have the worst grades. Where would you place yourself on this ladder? Please place a large “X” on the rung where you think you stand at this time in your life, relative to other people in your community.” Quon and Mcgrath (2014) reported 0.62 test–retest reliability for the scale.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

The self-report Arabic version of SDQ (Goodman, 1997) was used to assess mental health problems. It is a three-point (0-not true, 1-somewhat true, 2-certainly true) continuous scale with five subscales (each includes 5 items; emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity/ inattention, peer relationship problems, and prosocial behavior). The first four subscale scores can be summed to give a total difficulty score which is a measure of overall childhood mental health problems. The scale items also provide externalizing (the sum of the conduct and hyperactivity subscales) and internalizing scores (the sum of the emotional and peer problems) (Goodman & Goodman., 2009). We used these amalgamated scales to measure externalizing and internalizing problems. The instrument has good validity and reliability ratings (Goodman et. al., 2012). The authors reported 80% specificity and 85% sensitivity for the scale in identifying psychiatric diagnosis in 4–17-year-old children and adolescents (Goodman et al., 2004). The Cronbach’s alpha for externalizing and internalizing subscales in this study were. 71 and 0.73, respectively.

Depression Self Rating Scale for Children (DSRS-C)

The Arabic version of DSRS-C (Birleson, 1981) was used to measure depressive symptoms. It consists of 18 items scored on a three-point scale and the total score ranges from 0 to 36. Higher scores indicate greater depression. It is a widely used instrument and has been reported to have satisfactory validity and reliability ratings such as predictive validity, 0.80 test–retest reliability, and 0.65 to 0.95 item reliability (Birleson, 1981). In the current sample, the Cronbach’s alpha for the total score was 0.70.

Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS)

To assess anxiety symptoms, we used the Arabic version of SCAS (Spence, 1997). It is a four-point Likert Scale (0 = never to 3 = always), consisting of six subscales including panic attack and agoraphobia (9 items), separation anxiety (6 items), social phobia (6 items), fears of physical injury (5 items), obsessive–compulsive disorder (6 items), and generalized anxiety (6 items) and the total score gives a total anxiety score (38 items). Higher scores indicate greater anxiety symptoms. The SCAS has internal reliability coefficients ranging from 0.60 to 0.82 for the subscales and 0.92 for the total scale (Spence, 1998) and it is a widely used, reliable instrument for cross-cultural use (Orgiles et al., 2016). The Cronbach’s alpha for the total score in this sample was 0.89.

Procedure

The data were collected in an NGO-governed school in Istanbul as part of a project in 2019. The students, teachers, and managers of the school were from Syria. All of the correspondence carried out in Arabic. All of the materials (e.g., parental permission and participant information) were also provided in Arabic. First, the scales were introduced to the school management and they confirmed the administration of the scales. Second, the school management verbally asked for permission from the parents of the children. Because refugees are very sensitive about signing any kind of paper, the informed consent was obtained verbally. Approximately eighty percent of the parents agreed to their children participating in the study. The Ethics Committee approved the study. All of the participants agreed to be a volunteer in the study and filled out the questionnaires themselves after the consent form and the aim of the study were verbally explained to them. The administrators (psychologists) and translators were present in the classrooms throughout the data collection period.

Statistical Analysis

All the statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS Version 26.0. Missing data were less than 5%. In order to verify that the missing data were completely at random (MCAR), we applied the Little´s (1988) MCAR test. The test was not reliable, χ2(4660, N = 306) = 4680.12, p = 0.415, showing that the data can be assumed to be completely at random and missing values are assumed not to affect the analysis, and we ignored the missing data. Mediation and bootstrap analyses were carried out using the Hayes’ (2013) regression-based analytic approach and the PROCESS macro Version 3.5.3 for SPSS (Model 4). In order to test the significance of the mediation, we computed the Sobel test (Z) and used the indirect effect coefficient with %95 confidence intervals. The indirect effect was tested using a percentile bootstrap estimation approach with 5000 samples.

Results

Preliminary Analysis

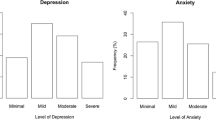

The prevalence of mental health problems is presented in Table 1. When participants’ (n = 285) total SDQ scores were categorized via the original bandings (Goodman & Goodman, 2009), 64.9% of the participants were categorized as ‘normal’, 19.3% were ‘borderline’, and 15.8% were ‘abnormal’.

Muris et al’s (2000) cut-off values indicating the probability of anxiety-related disorders were used to evaluate male (n = 125) and female (n = 148) participants’ SCAS scores separately. Accordingly, 97 boys (77.6%) scored higher than the cut-off value for boys (≥ 25), and 119 girls (80.4%) scored higher than the cut-off value for girls (≥ 36).

The clinical cut-off value (≥ 15) for depression (Birleson et al., 1987) was used to evaluate the participants’ (n = 279) DSRS-C scores. Accordingly, 101 participants (36.2%) were scored higher than the cut-off score.

Means, standard deviations, and gender differences are also presented in Table 1. Compared with boys, M = 7.79, SD = 2.06, girls, M = 6.84, SD = 2.10, reported significantly lower levels of subjective social status, t(287) = 3.87, p < 0.01, d = 0.456. No significant differences were found between genders in the DSRS-C and SDQ total scores. Further analyses with SDQ subscales revealed that girls, M = 4.20, SD = 2.40, reported higher levels of emotional problems when compared with boys, M = 3.36, SD = 2.20, t(290) = -3.20, p < 0.01, d = 0.375. However, girls, M = 2.87, SD = 1.82, reported lower levels of peer relationship problems than boys, M = 3.75, SD = 2.09, t(291) = 3.90, p < 0.01, d = 0.457. Girls, M = 2.21, SD = 1.52, also reported lower levels of conduct problems than boys, M = 3.22, SD = 1.99, t(295) = 4.96, p < 0.01, d = 0.576. No significant gender differences were found for the hyperactivity/inattention, p > 0.05. The results also showed that compared with boys, M = 37.58, SD = 15.09, girls, M = 52.32, SD = 16.70, scored significantly higher levels of SCAS, t(271) = -7.59, p < 0.01, d = 0.922. Similarly, girls’ scores were higher than boys’ scores for all of the SCAS subscales, namely, panic attack and agoraphobia, t(296) = -4.55, p < 0.01, d = 0.528, separation anxiety, t(296) = -6.15, p < 0.01, d = 0.714, social phobia, t(291) = -6.14, p < 0.01, d = 0.718, physical injury fears, t(294) = -10.33, p < 0.01, d = 1.202, obsessive–compulsive disorder, t(293) = -3.43, p < 0.01, d = 0.400, and generalized anxiety, t(285) = -5.92, p < 0.01, d = 0.700.

The Pearson’s r correlations between study variables are provided in Table 2. In addition, older age was significantly associated with increased hyperactivity/inattention, r = -0.25, p < 0.01, increased peer problems, r = -0.15, p < 0.05, increased DSRS-C, r = 0.14, p < 0.05, and decreased separation anxiety, r = 0.14, p < 0.01. The correlation between age and other study variables were not statistically significant, p > 0.05.

Mediation Analysis Results

We tested the mediating role of internalizing problems on the relationship between subjective social status and externalizing problems by measuring internalizing problems in three different ways. We measured internalizing behaviors via the sum of the emotional and peer problems subscales of the SDQ in the first, the DSRS-C in the second, and the SCAS in the third mediation analysis. None of the results was dramatically changed when age and gender were controlled.

The results of the first mediation analysis are displayed in Fig. 1. Accordingly, the direct effect of subjective social status score on externalizing problems was not significant, b = -0.09, t(273) = -0.10, p > 0.05. However, the subjective social status was a significant predictor of internalizing problems, b = -0.32, t(273) = -3.22, p < 0.01, which, in turn, significantly predicted externalizing problems, b = 0.43, t(272) = 8.92, p < 0.001. The direct effect of the subjective social status on externalizing problems was still not statistically significant when the internalizing problems were included in the model, b = 0.05, t(272) = 0.60, p > 0.05. Approximately 23% of the variance in externalizing problems was accounted for by the predictors, F(2,272) = 40.45, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.23. The indirect effect of the subjective social status score on the externalizing problems through internalizing problems was significant, abcs = -0.0925, CI = -0.1475, -0.0349. The Sobel test showed that internalizing problems mediated the relation between the subjective social status and externalizing problems, Z = 3.028, p < 0.01.

In the second mediation model (see Fig. 2), subjective social status demonstrated no significant relation to externalizing problems, b = -0.08, t (261) = -0.84, p > 0.05. The subjective social status was a significant predictor of DSRS-C, b = -0.62, t(261) = -4.27, p < 0.001, which, in turn, significantly predicted externalizing problems, b = 0.16, t(256) = 4.00, p < 0.001. The direct effect of the subjective social status on externalizing problems was still insignificant when the DSRS-C was included in the model, b = 0.02, t(260) = 0.18, p > 0.05. Approximately 6% of the variance in externalizing problems was accounted for by the predictors, F(2,260) = 8.40, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.06. The indirect effect of the subjective social status on the externalizing problems through DSRS-C was significant, abcs = -0.0636, CI = -0.1140, -0.0253. Similar to the first mediation analysis, the DSRS-C scores also mediated the relation between the subjective social status and externalizing problems, Z = -2.92, p < 0.01.

In the third mediation model (see Fig. 3), the separate mediating roles of SCAS and its subscales on the relationship between subjective social status and externalizing problems was examined. The indirect effect was only significant for the Panic-agoraphobia subscale. Accordingly, the results showed that subjective social status was a significant predictor of panic-agoraphobia scores, b = -0.34, t(277) = -2.64, p < 0.05, which, in turn, significantly predicted externalizing problems, b = 0.12, t(276) = 3.24, p < 0.01. The subjective social status demonstrated no significant relation to externalizing problems, b = -0.09, t (277) = 1.00, p > 0.05. The direct effect of subjective social status on the externalizing problems was still not significant when panic-agoraphobia was included in the model, b = -0.05, t(276) = -0.55, p > 0.05. Approximately 4% of the variance in externalizing problems was accounted for by the predictors, F(2,276) = 5.78, p < 0.01, R2 = 0.04. The indirect effect of subjective social status on the externalizing problems through panic-agoraphobia scores was significant, abcs = -0.0269, CI = -0.0598, -0.0031. In line with the first two mediation analyses, the panic-agoraphobia scores also mediated the relation between subjective social status and externalizing problems, Z = 2.05, p < 0.05.

Discussion

Consistent with previous studies with Syrian refugee adolescents in Turkey (e.g., Duren & Yalçın, 2021; Gormez et al., 2018; Kandemir et al., 2018) our study also showed high levels of mental health problems.

The main aim of the current study was to examine the relationship between subjective social status and mental health problems among Syrian refugee adolescents. The current results are in line with previous studies which used adult (Cundiff et al., 2011, 2013; Fleuriet & Sunil, 2018; Garza et al., 2017; Leu et al., 2008; Reitzel et al., 2017; Zell et al., 2018) and adolescent samples (Goodman et al., 2001; Lemeshow et al., 2008; Finkelstein et al., 2006; Ritterman et al., 2009; Sweeting & Hunt, 2014, 2015). Confirming and extending previous findings, our results demonstrated that lower levels of subjective social status is associated with increasing levels of emotional problems, hyperactivity/inattention, depression, panic attack/agoraphobia, physical injury fears, and general anxiety. Further, the results supported our main hypothesis by showing that internalizing problems mediated the relationship between subjective social status and externalizing problems. This mediation effect was confirmed by three separate analyses where internalizing problems were defined/measured in three different ways (emotional and peer problems, depression, and panic attack-agoraphobia, respectively). However, the direct effects of subjective social status on externalizing problems were not significant. This suggests that refugee adolescents who place themselves low in their community are more likely to have externalizing problem behaviors than adolescents who place themselves high in their community because their low-status perception increases their internalizing problem behaviors.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that examined the mediation effect of internalizing problems on the relationship between subjective social status and externalizing problems. Moreover, considering the lack of studies focusing on the subjective social status of the refugees, the present research is quite important for contributing to our understanding of the relationship between perceived subjective social status in communities and mental health problems in refugee populations. Overall, the results show that community subjective social status could be a crucial factor for several aspects of refugee mental health.

Implications

These results have both theoretical and practical implications. Firstly, our results confirm the directional model of the association between internalizing and externalizing problems (e.g., Bittner et al., 2007; Ritakallio et al., 2008; Vitaro et al., 2000) by showing the mediating role of internalizing problem behaviors in the relationship between subjective social status and externalizing problem behaviors. Secondly, the current results may also provide applicative insights for refugee mental health intervention programs. In a way, the results imply that encouraging the social equality-based hierarchy-free structuring of the communities would help to prevent mental health problems of refugee adolescents. Moreover, these results suggest the priority of internalizing problems of the adolescents for the interventions that may focus on the association between community subjective social status and externalizing problems. Future studies may consider using online photovoice methodology and community-based participatory approaches to replicate the current findings in a more comprehensive way. These future studies may contribute to understanding of the psychological nature of the status perceptions in their community, its relation with mental health problems and how this knowledge could be used for improving mental health.

Limitations

A number of limitations of the study need to be stated. First, the cross-sectional design limits the causal interpretation of the data and could not rule out the possibility of reverse causation. Second, mental health problems were measured only by self-report questionnaires. Although we have used self-report measurements with high validity and reliability, one should not expect them to be as effective as the direct assessment by mental health specialists to evaluate mental health problems. And third, because we recruited participants from school settings, we cannot generalize the current findings to all refugee adolescents who either live in refugee camps or could not attend school. Readers should be aware of selection bias and generalizability of the current results because we collected the data only from a single school in a single big urban city. Moreover, approximately twenty percent of the parents did not agree their children to participate in the study. However, readers should also consider that the sample is from a very hard-to-reach population and that the current results on the prevalence of mental health problems are consistent with the results of the previous studies that conducted in the same population.

New Contribution to the Literature

Despite the limitations, the present study represents an initial step in exploring the community-related factors related to mental health problems of refugee adolescents. Specifically, the current study provides a simple model portraying the relationship between community subjective social status and mental health problems. As such, it provides support for the idea that adolescent’s community subjective social status may affect internalizing problems directly and externalizing problems indirectly via internalizing problems. Overall, this model confirms the directional approach to the internal and external problems and emphasizes the importance of community subjective social status on internalizing and externalizing problems of refugee adolescents.

References

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4-8, YSR, and TRF Profiles. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry.

Achenbach, T. M., Ivanova, M. Y., Rescorla, L. A., Turner, L. V., & Althoff, R. R. (2016). Internalizing/externalizing problems: Review and recommendations for clinical and research applications. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(8), 647–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.05.012

Adler, N., & Stewart, J. (2007). The MacArthur scale of subjective social status. MacArthur Research Network on SES & Health.

Adler, N. E., Epel, E. S., Castellazzo, G., & Ickovics, J. R. (2000). Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy, white women. Health Psychology, 19(6), 586–592. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.19.6.586

Birleson, P. (1981). The validity of depressive disorder in childhood and the development of a self-rating scale: A research report. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 22(1), 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1981.tb00533.x

Birleson, P., Hudson, I., Buchanan, D. G., & Wolff, S. (1987). Clinical evaluation of a self-rating scale for depressive disorder in childhood (Depression Self-Rating Scale). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 28(1), 43–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1987.tb00651.x

Bittner, A., Egger, H. L., Erkanli, A., Costello, J. E., Foley, D. L., & Angold, A. (2007). What do childhood anxiety disorders predict? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48, 1174–1183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01812.x

Chan, G., Barnes-Holmes, D., Barnes-Holmes, Y., & Stewart, I. (2009). Implicit attitudes to work and leisure among North American and Irish individuals: A preliminary study. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 9(3), 317–334.

Correa-Velez, I., Gifford, S. M., & Barnett, A. G. (2010). Longing to belong: Social inclusion and wellbeing among youth with refugee backgrounds in the first three years in Melbourne. Australia. Social Science & Medicine, 71(8), 1399–1408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.018

Cundiff, J. M., Smith, T. W., Uchino, B. N., & Berg, C. A. (2011). An interpersonal analysis of subjective social status and psychosocial risk. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 30(1), 47–74. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2011.30.1.47

Cundiff, J. M., Smith, T. W., Uchino, B. N., & Berg, C. A. (2013). Subjective social status: Construct validity and associations with psychosocial vulnerability and self-rated health. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 20(1), 148–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-011-9206-1

Davis, J. A. (1956). Status symbols and the measurement of status perception. Sociometry, 19, 154–165. https://doi.org/10.2307/2785629

Duren, R., & Yalçın, Ö. (2021). Social capital and mental health problems among Syrian refugee adolescents: The mediating roles of perceived social support and post-traumatic symptoms. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 67(3), 243–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020945355

Ellis, B. H., MacDonald, H. Z., Lincoln, A. K., & Cabral, H. J. (2008). Mental health of Somali adolescent refugees: The role of trauma, stress, and perceived discrimination. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(2), 184–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.184

Finkelstein, D. M., Kubzansky, L. D., & Goodman, E. (2006). Social status, stress, and adolescent smoking. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(5), 678–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.011

Fleuriet, J., & Sunil, T. (2018). The Latina birth weight paradox: The role of subjective social status. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 5(4), 747–757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-017-0419-0

Garey, L., Reitzel, L. R., Kendzor, D. E., & Businelle, M. S. (2016). The potential explanatory role of perceived stress in associations between subjective social status and health-related quality of life among homeless smokers. Behavior Modification, 40(1–2), 303–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445515612396

Garza, J. R., Glenn, B. A., Mistry, R. S., Ponce, N. A., & Zimmerman, F. J. (2017). Subjective social status and self-reported health among US-born and immigrant Latinos. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 19(1), 108–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-016-0346-x

Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(5), 581–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

Goodman, A., & Goodman, R. (2009). Strengths and difficulties questionnaire as a dimensional measure of child mental health. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(4), 400–403. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181985068

Goodman, E., Adler, N. E., Kawachi, I., Frazier, A. L., Huang, B., & Colditz, G. A. (2001). Adolescents’ perceptions of social status: Development and evaluation of a new indicator. Pediatrics, 108(2), e31–e31. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.108.2.e31

Goodman, R., Ford, T., Corbin, T., & Meltzer, H. (2004). Using the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ) multi-informant algorithm to screen looked-after children for psychiatric disorders. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 13(2), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-004-2005-3

Goodman, E., Maxwell, S., Malspeis, S., & Adler, N. (2015). Developmental trajectories of subjective social status. Pediatrics, 136(3), e633–e640. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-1300

Goodman, A., Heiervang, E., Fleitlich-Bilyk, B., Alyahri, A., Patel, V., Mullick, M. S., ... Goodman, R. (2012). Crossnational differences in questionnaires do not necessarily reflect comparable differences in disorder prevalence. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47(8), 1321-1331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0440-2

Gormez, V., Kılıç, H. N., Orengul, A. C., Demir, M. N., Demirlikan, Ş., Demirbaş, S., ... & Semerci, B. (2018). Psychopathology and associated risk factors among forcibly displaced Syrian children and adolescents. Journal of immigrant and minority health, 20(3), 529-535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-017-0680-7

Hayes, A. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Guilford Press.

Kandemir, H., Karataş, H., Çeri, V., Solmaz, F., Kandemir, S. B., & Solmaz, A. (2018). Prevalence of war-related adverse events, depression and anxiety among Syrian refugee children settled in Turkey. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 27(11), 1513–1517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1178-0

Lemeshow, A. R., Fisher, L., Goodman, E., Kawachi, I., Berkey, C. S., & Colditz, G. A. (2008). Subjective social status in the school and change in adiposity in female adolescents: Findings from a prospective cohort study. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 162(1), 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.11

Leu, J., Yen, I. H., Gansky, S. A., Walton, E., Adler, N. E., & Takeuchi, D. T. (2008). The association between subjective social status and mental health among Asian immigrants: Investigating the influence of age at immigration. Social Science & Medicine, 66(5), 1152–1164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.028

Little, R. J. A. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83, 1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722

Lurie, I., & Nakash, O. (2015). Exposure to trauma and forced migration: Mental health and acculturation patterns among asylum seekers in Israel. In Trauma and Migration (pp. 139–156). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-17335-1_10

Mu, C., Jester, D. J., Cawthon, P. M., Stone, K. L., & Lee, S. (2021). Subjective social status moderates back pain and mental health in older men. Aging & Mental Health, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1899133

Murad, S. D., Joung, I. M., van Lenthe, F. J., Bengi-Arslan, L., & Crijnen, A. A. (2003). Predictors of self-reported problem behaviours in Turkish immigrant and Dutch adolescents in the Netherlands. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44(3), 412–423. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00131

Muris, P., Schmidt, H., & Merckelbach, H. (2000). Correlations among two self-report questionnaires for measuring DSM-defined anxiety disorder symptoms in children: The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders and the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 28(2), 333–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00102-6

Orgiles, M., Fernández-Martínez, I., Guillen-Riquelme, A., Espada, J. P., & Essau, C. A. (2016). A systematic review of the factor structure and reliability of the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale. Journal of Affective Disorders, 190, 333–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.055

Quon, E. C., & McGrath, J. J. (2014). Subjective socioeconomic status and adolescent health: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 33(5), 433–447. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033716

Reitzel, L. R., Childress, S. D., Obasi, E. M., Garey, L., Vidrine, D. J., McNeill, L. H., & Zvolensky, M. J. (2017). Interactive effects of anxiety sensitivity and subjective social status on psychological symptomatology in Black adults. Behavioral Medicine, 43(4), 268–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2016.1150805

Ritakallio, M., Koivisto, A., von der Pahlen, B., Pelkonen, M., Marttunen, M., & Kaltiala-Heino, R. (2008). Continuity, comorbidity and longitudinal associations between depression and antisocial behavior in middle adolescence: A 2-year prospective follow-up study. Journal of Adolescence, 31, 355–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.06.006

Ritterman, M. L., Fernald, L. C., Ozer, E. J., Adler, N. E., Gutierrez, J. P., & Syme, S. L. (2009). Objective and subjective social class gradients for substance use among Mexican adolescents. Social Science & Medicine, 68(10), 1843–1851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.048

Spence, S. H. (1997). Structure of anxiety symptoms among children: A confirmatory factor-analytic study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106(2), 280–297. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.106.2.280

Spence, S. H. (1998). A measure of anxiety symptoms among children. Behaviour Research & Therapy, 36, 545–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00034-5

Stone, L. L., Otten, R., Engels, R. C., Kuijpers, R. C., & Janssens, J. M. (2015, October). Relations between internalizing and externalizing problems in early childhood. In Child & youth care forum (Vol. 44, No. 5, pp. 635–653). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-014-9296-4

Sweeting, H., & Hunt, K. (2014). Adolescent socio-economic and school-based social status, health and well-being. Social Science & Medicine, 121, 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.037

Sweeting, H., & Hunt, K. (2015). Adolescent socioeconomic and school-based social status, smoking, and drinking. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(1), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.03.020

Vitaro, F., Brendgen, M., & Tremblay, R. (2000). Influence of deviant friends on delinquency: Searching for moderator variables. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 28, 313–325. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005188108461

Zell, E., Strickhouser, J. E., & Krizan, Z. (2018). Subjective social status and health: A meta-analysis of community and society ladders. Health Psychology, 37(10), 979–987. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000667

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all of the participants who took part in the study. Our sincere thanks to the school principal and teachers for their kind support. And we would like to give our special thanks to the staff and managers of the Dunya Doktorlari Dernegi.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to all parts of the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed Consent

All participants provided informed written consent prior to starting the questionnaire, and the data was collected anonymously. The Study protocol and informed consent form were approved by the Ethical Review Board of Dunya Doktorlari Dernegi. The study has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Düren, R., Yalçın, Ö. How does subjective social status affect internalizing and externalizing problems among Syrian refugee adolescents?. Curr Psychol 42, 17951–17959 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03002-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03002-4