Abstract

Prior studies comparing Syrian refugee adolescents to their native peers in the same region have found higher anxiety and lower life satisfaction. Therefore, identifying regulatory variables is crucial for implementing support programs. This study examined the mediating effect of peer relationships and the moderating effect of being a refugee or native adolescent on the relationship between adolescent anxiety and life satisfaction across different samples. Participants and setting: The study included 2,336 adolescents aged 11–19 (M = 14.79, SD = 1.04). Participants completed the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders, Satisfaction with Life Scale, and Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. The mediation and moderation effects were analyzed with the path analysis codes written on Mplus 8.3. SPSS 26 was used for descriptive statistics and group comparisons. The findings showed that peer relationships mediate adolescent anxiety and life satisfaction, and this relationship is moderated according to whether the participants are native adolescents or refugee adolescents. This study highlights the significant associations between peer relationships, adolescent anxiety, and life satisfaction and the moderating role of the participant identity. The findings may inform psychological interventions to improve Syrian refugee adolescents' mental health and well-being. These findings may also have implications for policies and programs aimed at supporting the integration of Syrian refugee adolescents in host communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As a result of the ongoing civil war in Syria for over a decade, millions of Syrians have been forced to leave their homes [131]. Turkey has emerged as the most important destination for Syrians who have been forced to flee their homeland following the war [131]. In this context, Turkey is hosting 3,648,983 Syrian refugees [49]. Additionally, many Syrian refugees worldwide and in Turkey consist of children and adolescents [17, 43, 49]. Although settling in a different country affects the entire family, children and adolescents tend to attach more emotions and significance to this experience than adults, and they are more greatly impacted by it [5, 14, 83].

Anxiety and satisfaction with life among refugee adolescents

Adolescence is a crucial stage marked by significant cognitive and physical changes. The challenges inherent in this period are further intensified when adolescents undergo stressful life events, such as relocating to a new country or experiencing the impact of war [41, 47]. These adolescents have been exposed to traumatic experiences, challenging living conditions, separation from family members, and the loss of loved ones [86]. A study conducted by Özer et al. [97] on refugee adolescents in Turkey reported that adolescents between the ages of 9 and 18 had experienced numerous traumatic events, with 74% witnessing the loss of a loved one. Adolescents who are in a critical period of their lives after resettlement are particularly at higher risk and face significant problems [10, 71].

In addition to the stressful experiences they faced in their own countries and the everyday stress of adolescence, factors such as family traumas in the host country, differences in the education system, and language barriers contribute to significant challenges and increased vulnerability for refugees after resettlement [13, 48, 69]. Bean et al. [10] and Khamis [69] state in their studies on refugee adolescents that a significant relationship exists between stressful life events and psychiatric disorders. Anxiety is one of the most common psychiatric disorders observed in these adolescents [21, 55, 57, 58, 135]. Many researchers in the literature, both in Turkey and in different countries, have conducted studies on Syrian refugee adolescents and have noted that at least half of these adolescents exhibit symptoms of anxiety [25, 52, 64, 66]. Similarly, studies comparing refugee adolescent samples with local samples have found that refugee adolescents have higher rates of anxiety compared to the local sample [18, 45, 88, 110, 134, 146].

Children and adolescents affected by war not only experience trauma and related psychopathologies but also exhibit various emotional and behavioral problems. These problems include self-harm, involvement in criminal activities, hyperarousal, decreased life satisfaction, and decreased social functioning [6, 13]. Indeed, in a study conducted by Al-Masri et al. [3] comparing Syrian immigrants with the local population in Germany, it was found that Syrian immigrants had lower life satisfaction than the local population.

The influence of post-migration social relationships on anxiety and satisfaction with life

Linking the traumatic experiences of refugee adolescents solely to pre-migration stress factors leaves out many other significant issues [13]. Therefore, studies conducted after resettlement become crucial. After settling in the host country, refugee adolescents are exposed to negative experiences such as language problems, difficulties in adapting to the new environment, and discrimination [80]. Furthermore, there are studies indicating that refugee adolescents struggle to adapt to the school environment, experience peer bullying, and encounter peer-related problems [31, 44, 108, 145].

Adolescents are influenced by how their peers perceive them [92]. Moreover, negative experiences in their social relationships can have psychiatric consequences for adolescents [95]. Many researchers in the literature state that peer interactions impact adolescents' development and well-being [27, 105]. For example, it is known that there is a negative relationship between social support and anxiety during adolescence [87, 114, 115]. For instance, a study conducted by Havewala et al. [56] suggests that receiving support from peers and classmates can decrease adolescent anxiety levels. Al-Shatanawi et al. [4] state that social isolation and loneliness are among the observed primary psychiatric disorders in Syrian refugee adolescents. Therefore, peer relationships are highly important for refugee adolescents and play a critical role in reducing the psychiatric symptoms observed in this sample [15, 19, 69].

The devastating effects of traumatic experiences and exposure to war cannot be solely alleviated through positive relationships with peers. However, refugee adolescents, especially those who have to resettle in a different country and spend more time with their peers, are more frequently exposed to stress factors originating from their peers [106]. Establishing positive relationships with local peers after resettlement helps reduce adjustment difficulties and increase life satisfaction for these refugee adolescents [31, 38, 46, 81, 99, 112, 130, 133].

It is well-known that adolescence is a period characterized by uncertainties, and it is the time when anxiety disorders are most commonly observed [26, 39, 84, 101, 104, 118,119,120, 139, 141]. Therefore, anxiety is an important variable for native Turkish adolescents as well. Anxiety in Turkish adolescents is considered one of the main factors negatively impacting their life satisfaction [67].

In light of these findings, it is expected that peer relationships play a mediating role in the relationship between anxiety and life satisfaction. Thus, uncovering the role of peer relationships in the anxiety-life satisfaction relationship for both native and Syrian refugee adolescents is a crucial aspect that needs to be explored.

The current study

Since the beginning of the war in Syria, many researchers have conducted studies on Syrian refugees and refugee adolescents (e.g., [12, 20, 79, 137]). When examining the limited number of studies conducted on refugee adolescents, it can be observed that studies with Syrian adolescents mainly focus on pre-migration risk factors. Although some studies have explored factors such as family [41] and well-being [103] after the resettlement of refugee adolescents in the host country, peer relationships have been neglected in this sample [32]. In this context, it is evident that sufficient attention has not been given to protective factors for the mental health of Syrian refugee adolescents.

Moving to a new country is a stressful life event that causes significant changes in one's life and can have lasting negative effects from childhood to adulthood, making refugees vulnerable to mental health problems [62]. It is known that 70% of adult mental health problems begin in adolescence [33]. The high prevalence of anxiety among Syrian refugee adolescents compared to the general population, the strong predictor of potential negative outcomes in adulthood associated with adolescent anxiety [100], and its co-occurrence with various psychiatric disorders [42], low life satisfaction [8, 82], and low academic performance [70, 121], highlight the importance of interventions during this period.

Based on these findings, it is important to identify potential risk and social factors for anxiety disorders, low life satisfaction, and social adaptation among refugee adolescents. Although there have been numerous studies on refugee adolescents in the literature, a limited number of studies examine the impact of peer relationships. The present study aims to investigate the mediating effect of peer relationships on anxiety levels and life satisfaction and to explore the potential moderating effect of being a refugee adolescent or a local Turkish adolescent on this mediation mechanism in Turkey.

Research hypotheses

The present study assumes that (a) there will be a negative relationship between adolescent anxiety and life satisfaction, (b) adolescent anxiety will be negatively associated with peer relationships, (c) peer relationships will be positively related to life satisfaction, (d) peer relationships will mediate the relationship between adolescent anxiety and life satisfaction, and (e) being a local Turkish adolescent or a Syrian refugee adolescent will have a moderating effect on this mediation relationship (See Fig. 1).

Method

Participants

This study’s Sample included 2,336 individuals aged between 14 and 19 years Turkish Sample: M = 15.02, SD = 0.86; Syrian Sample: M = 14.56, SD = 1.15). Data for the study were collected from two distinct groups comprising 1148 Syrian adolescent refugees (Sample 2) who migrated to Turkey due to the war and 1188 Turkish students (Sample 1). Of the total participants, 1532 were female, and 804 were male. The data collection process was conducted across four different cities in Turkey, namely Aksaray, Hatay, Kahramanmaraş, and Mersin.

Procedure

An exploratory quantitative research design guided the cross-sectional sampling method to recruit adolescents from diverse schools and non-governmental organizations in Turkey. The selection of the research design was based on the strengths of the established quantitative methods, allowing for flexible adoption of the method. Relying on convenience sampling, public schools and non-governmental organizations in Turkey were approached and invited to participate in the research. Written informed consent was obtained from a parent or legal guardian, followed by written assent of the participant if they were younger than 18. Written consent was obtained from the participants at least 18 years of age. Students who completed the consent form knew how to read and write in their native language (Turkish or Arabic) and volunteered to participate in the study were included in the data collection process. As a result, the participation rate in the research was calculated as 89%. Considering the recommendations of Bryman and Cramer [23] and Tabachnick and Fidel [123] to calculate the sample size according to the number of scale items, 2568 students who agreed to participate in the study were included. After invalid data was checked, the number of participants decreased to 2,336.

During the data collection process, either one of the researchers or the psychological counselor appointed by the relevant educational institution supervised the students’ possible problems by addressing their queries and concerns. During this process, the researcher or the psychological counselor provided no guidance, and the students freely responded. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the data collection process for Syrian adolescents was facilitated by a researcher fluent in Arabic, their native language. Turkish and Arabic scales were applied to the participants in the data collection process according to their native languages. The present study complied with the regulations stipulated by the University Ethics Committee, and data collection was performed between January and April 2023.

Measurements

Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) was used in the current study to assess anxiety symptoms. The SCARED was developed by Birmaher et al. [16] to evaluate anxiety disorder symptoms in children and adolescents as well as for screening purposes. The SCARED scale consists of 41 items (e.g., I worry about how well I'm doing things) that are scored on a 3-point Likert scale (0 = Not true, 2 = Very true or often true) and includes five subscales measuring panic disorder, somatic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety, and social anxiety. The total score ranges from 0 to 82, with higher scores indicating higher levels of the corresponding trait. However, a score of 25 or higher on the SCARED indicates a warning for anxiety disorders.

The scale was adapted to Turkish culture by Cakmakci [24]. In this study, Cronbach's alpha internal consistency coefficient of the scale was reported to be between 0.74 and.93.The scale adapted to Arabic culture by Hariz et al. [54]. In this study, Cronbach's alpha internal consistency coefficient of the scale was reported to be between 0.65 and 0.89. In Birmaher et al.'s [16] study, Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient for the scale and subscales ranged from 0.74 to 0.93, and the test–retest reliability coefficient ranged from 0.70 to 0.90. In the current study, Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient for SCARED was calculated as 0.90 for the Turkish sample, 0.85 for the Syrian sample and 0.92 for the whole.

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) was used to assess participants' life satisfaction. The SWLS was developed by Diener et al. [35] to evaluate an individual's subjective evaluation of their overall life satisfaction. The scale consists of 5 items (e.g. I have a life close to my ideals in many ways) and a single subscale evaluated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all appropriate, 7 = Very appropriate). An overall score on the SWLS ranges from 5 to 35, with higher scores indicating greater life satisfaction. Köker [74] adapted the scale to Turkish culture. In this study, the test–retest reliability coefficient was 0.85. Yetim [144] reported a Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient of 0.86 and a test–retest reliability coefficient of 0.75. Abdallah [1] adapted the scale to Arabic culture. In this study, Cronbach's alpha internal consistency coefficient for the scale's total score was calculated as 0.79. In the current study, Cronbach's alpha internal consistency coefficient was calculated as 0.75 for the Turkish sample and 0.70 for the Syrian sample.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) originally developed by Goodman [51], was used to measure peer problems. The SDQ is a widely used tool to assess emotional and behavioral problems in children aged 4–16. The SDQ contains 25 items, each scored on a 3-point Likert scale (0 = Not True, 1 = Somewhat True, 2 = Certainly True), and is composed of five subscales: hyperactivity/inattention, behavioral problems, emotional problems, peer problems, and prosocial behavior. The peer problems subscale, which consists of five items, was selected for the current study. The total score that can be obtained from the subscale varies between 0 and 10, and an increase in the score indicates a positive peer relationship.

As proposed for adolescents, some items in this subscale appear to reflect loneliness (e.g., feeling rather solitary, tending to be alone, having at least one good friend) and sociability (e.g., generally liked by other people my age; getting on better with adults than with people my own age) [140]. Additionally, the peer problems subscale has been shown to moderately correlate with adolescents' internalizing symptoms [96]. Therefore, we chose this for the current study.

Güvenir et al. [53] adapted the scale to Turkish culture. In this study, Cronbach's alpha internal consistency coefficient for the peer problems subscale was 0.37. The scale was adapted to the Arabic adolescent sample by Mukhaini et al. [90] and Emam et al. [40]. In these studies, Cronbach's alpha internal consistency coefficient for peer problems subscale was reported as 0.30 and 0.40, respectively. The present study calculated Cronbach's alpha internal consistency coefficient as 0.70 and 0.40 for the Turkish and Syrian samples, respectively.

Statistical approach

The moderated mediating effect occurs when the relationship between the independent and dependent variables varies at different levels of the moderator variable [91]. With this perspective in our study, we tested the second-stage moderated mediation effect, which means the moderator (e.g., participant sample) moderated the association between the mediator (e.g., peer relationship) and satisfaction with life.

In this study, we employed SPSS 26.0 and Mplus 8.3 [93] to conduct descriptive statistics and moderated mediation analyses. A pre-determined alpha level of 0.05 was used to determine the statistical significance of all analyses conducted in this study. Before the analysis, the normality assumptions of the data were tested using the skewness and kurtosis coefficients. As a result of this analysis, it was determined that all research variables were within acceptable limits [50], maximum skewness = 1.191, maximum kurtosis = 1.489). We conducted descriptive statistics and correlation analysis using SPSS 26.0 first. Subsequently, we employed Mplus 8.3 for the analysis of moderated mediation. When the moderated mediating effect was significant, we followed Cohen et al.'s [29] recommendations and plotted the two slopes, interpreting the nature of these multiple models (Table 1).

Results

Preliminary analyses

The means, standard deviations, skewness, kurtosis, and Cronbach alpha internal consistency coefficients among the variables are shown in Table 2 according to the sample of the participants.

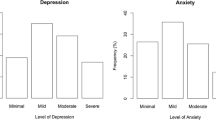

The means, standard deviations, and point biserial correlations among the variables are shown in Table 3. Point biserial correlation is the value of the Pearson product correlation when one of the variables is dichotomous and the other is metric [73, 113]. As we expected, adolescent anxiety is negatively correlated with life satisfaction (r = − 0.26, p < 0.01) and peer relationships (r = − 0.10, p < 0.01). In contrast, peer relationships are positively correlated with life satisfaction (r = 0.18, p < 0.01). ANOVA analysis was conducted to examine whether the anxiety and life satisfaction rates of the participants changed according to the local or refugee sample (see Table 4). According to the results of the analysis, it was observed that the adolescent anxiety [f(1,2335) = 1745,852, p = 0.000] levels of the Syrian refugee adolescents were higher than the local sample, and their life satisfaction was lower [f(1,2335) = 331,593, p = 0.000].

Before testing the hypotheses, we conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) by utilizing Mplus to examine the validity of our measurement model. As shown in Table 5, the model fit indices of the three-factor model showed an acceptable fit [χ2(1275, N = 2356) = 4191.28, χ2/df = 3,28, root mean square error approximation (RMSEA) = 0.048, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.90, Tucker‒Lewis index (TLI) = 0.89, Tucker‒Lewis index (SRMR) = 0.040] and were better than other alternative models examined. The adequate cut-off values for these indices were less than 3 for the χ2/df, < 0.08 for the RMSEA and SRMR, and > 0.90 for the CFI and TLI [59, 111]. We, therefore, conclude that these results supported the distinctiveness of the measurements used in this study.

Mediating results

The indirect effect of peer relationships in determining the mediating role of adolescent anxiety on life satisfaction was examined using Mplus. In this stage, the mediation-moderation model was tested (see Fig. 1). Given that the model is a fully saturated model, the fit indices were not reported. The chi-square statistic for model fit was significant (p = 0.000). Additionally, the RMSEA and SRMR values being less than 0.08 within the 95% confidence interval indicate a good model fit.

The analysis results revealed a statistically significant negative relationship between adolescent anxiety and life satisfaction (B = − 0.425, p = 0.000). Furthermore, a significant relationship was found between peer relationships and adolescent anxiety (B = − 0.016, p = 0.000). Moreover, our findings demonstrate that the indirect effect of adolescent anxiety on life satisfaction through peer relationships is significant (B = 0.194, p = 0.000). The confidence interval values [95% CI (0.116–0.273)] did not include zero, indicating a significant indirect effect. The values related to the mediation-moderation model are presented in Table 6.

Moderation results

Lastly, this study examines the moderating role of peer relationships in the indirect effect of adolescent anxiety on life satisfaction within the participant sample. To investigate this relationship, the interaction between adolescent anxiety and the participant sample was initially examined, revealing that this interaction term was positively and significantly related to life satisfaction (B = 0.270, p = 0.000). It was concluded that the indirect effect of adolescent anxiety on life satisfaction through peer relationships was determined to a high degree by the participant sample, with an effect size of 0.27 [95% CI (0.231–0.309)]. Additionally, Fig. 2 gives a visual demonstration of the conditional effects of the values (min- and high) of the mediator. The f2 statistic was used to calculate the effect size of the interaction term [2]. Accordingly, f2 value was calculated as 0.24. This value was interpreted as a moderate effect in line with Cohen's guidelines for interpreting the f2 [28]. Following the significance of the moderated mediating effect, we adhered to Cohen et al.'s [29] suggestions in Fig. 3a and b. The visualization illustrates the moderating effect of peer relationships on the relationship between anxiety and life satisfaction among local Turkish and Syrian refugee adolescents. We plotted and interpreted the nature of the two slopes in these multiple models.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the mediating role of peer relationships in the relationship between adolescent anxiety and life satisfaction among Syrian refugee adolescents who sought refuge in Turkey due to the Syrian civil war, which is one of the most significant humanitarian crises in recent history, and local Turkish adolescents. Additionally, the potential moderating effect of being a refugee or a local adolescent on this relationship is investigated. The findings of our study confirm the expected negative relationship between adolescent anxiety and life satisfaction, as well as the negative relationship between adolescent anxiety and peer relationships, which are consistent with relevant literature. Furthermore, our results validate the mediating role of peer relationships in the relationship between adolescent anxiety and life satisfaction.

The current study is in line with previous research conducted on Syrian refugee adolescents who were forced to migrate to Turkey and other countries due to war [64, 68], Llyod 2019, [66, 142]. Consistent with these previous studies, it has been determined that Syrian refugee adolescents exhibit high levels of anxiety symptoms. In addition, consistent with previous studies comparing refugee adolescents and local adolescents in the same region [37], our study found that Syrian refugee adolescents have higher rates of anxiety compared to the local sample [88, 146]. Furthermore, in line with the literature, our findings indicate that the life satisfaction of Syrian refugee adolescents is lower than that of the local sample [3]. Moreover, consistent with the findings of previous studies, a negative relationship between life satisfaction and anxiety symptoms has been identified [7, 63, 129].

The main assumption of this study is that the role of peer relationships in the relationship between adolescent anxiety and life satisfaction will vary depending on whether the participants are native adolescents or refugee adolescents. Adolescence is when young people increasingly distance themselves from their parents, and their relationships with peers become more important [75, 138]. During this period, refugee adolescents, in particular, need social support more than native samples [72]. Refugee adolescents are at a higher risk for psychiatric disorders compared to local samples [134]. Many of the psychiatric disorders experienced during this period tend to be long-lasting and persistent [94]. The negative experiences with peers during this period continue to have an impact in adulthood [112], and they can also serve as precursors to many psychiatric disorders [85, 112].

Studies have shown that a significant portion of refugees lack access to mental health services [76, 102]. However, despite the high rates of psychiatric disorders observed in refugee adolescents, it should not be overlooked that a considerable portion of this population does not develop any mental health problems. This highlights the importance of focusing on the protective factors that preserve the mental health of refugee adolescents [109].

Due to various negative factors that can impact adolescents' adjustment following forced migration, understanding the role of peer relationships is crucial. Literature has consistently highlighted the significance of peer relationships in shaping developmental outcomes during childhood and adolescence [77, 132]. For example, Kan and McHale [65], Victor et al. [132], and Salk et al. [107] suggest that adolescents who do not have healthy peer relationships are more likely to exhibit internalizing problems such as depression and anxiety. Adolescents who are forced to migrate may experience stressors related to relocation [30], acculturation [89], and transitioning to a new school environment [61]. Peer relationships can enhance adolescents' self-esteem and coping skills, while such relationships can also potentially mitigate internalizing problems commonly experienced during adolescence [122, 136]. Following this perspective, problems with peers during adolescence can indicate future problems [60]. This is particularly relevant for vulnerable samples, such as refugees [112]. Support from peers positively affects the post-migration adjustment process for adolescents [9].

It is crucial to identify factors that can promote the adaptation of adolescents who experience stressful life events and difficulties during their migration to a host country [128]. Previous studies have shown the role of different psychological factors in supporting the psychological well-being of Syrian adolescents against stressful life events [143]. Consistent with the available literature, the present study highlights the potential protective effect of peer relationships to alleviate anxiety symptoms and increase life satisfaction among Syrian refugee adolescents.

When examining Fig. 3a, which illustrates the impact of peer relationships on life satisfaction, it can be observed that an increase in peer relationships in the Syrian refugee adolescent sample leads to a more significant increase in life satisfaction than in the local sample. Similarly, when examining Fig. 3b, which visualizes the relationship between life satisfaction and adolescent anxiety based on whether they are local or refugee adolescents, it can be seen that strong peer relationships in Syrian refugee adolescents have a positive effect on increasing life satisfaction in the context of the anxiety-life satisfaction relationship. As a result, this study, in line with the existing literature, highlights the potential protective effect of focusing on peer relationships in alleviating anxiety symptoms and improving low levels of life satisfaction experienced by Syrian refugee adolescents.

According to our findings, one possible reason why peer relationships in local samples do not lead to significant changes in life satisfaction as they do in Syrian refugee adolescents could be attributed to the fact that the local sample benefits from different psychosocial support sources, such as established strong family ties and interactions with peers in different social environments. On the other hand, Syrian adolescents may experience disruptions in their families after resettlement, and their primary sources of socialization may be limited to the school environment and the social interactions within it. This suggests that peer relationships may be more explanatory for this sample.

Contributions

This study adds to the existing literature by examining the moderator effect of being a native adolescent or refugee adolescent on the relationship between adolescent anxiety and life satisfaction in both native and refugee adolescents residing in the same region. To our knowledge, this study is one of the first to examine this relationship in the context of Syrian refugee adolescents in Turkey. Furthermore, the findings suggest that peer relationships play a crucial role in promoting well-being, specifically life satisfaction, in refugee adolescents. This study sheds light on the importance of peer relationships for refugee adolescents in a host country.

These results have important implications for developing well-being intervention programs for refugee adolescents that target their peer relationships. However, it is important to note that native adolescents may also face peer problems and may require social support, in addition to adaptation problems caused by forced migration. Future research from this perspective could demonstrate the effects of native adolescents’ peer problems on the anxiety-life satisfaction relationship. Overall, the current findings underscore the significance of peer relationships in enhancing the mental well-being of Syrian refugee adolescents living in Turkey. The results support designing interventions that target the development of positive peer relationships to promote mental health among refugee adolescents.

Ecological Systems Theory (EST) is a conceptual model that proposes the importance of considering environmental conditions alongside individual and genetic factors [22]. EST includes four interrelated layers (micro, meso, exo, and macro systems) that must be considered together. Research emphasizes the importance of considering all layers to fully understand immigrant youth's social interactions and experiences [124, 125]. One example is Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR), in which researchers encourage community-based organizations and stakeholders to participate in the research process to create culturally relevant interventions [11, 34]. Adopting the Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) approach in future research may contribute to developing intercultural sensitivity and forming safe peer spaces and social networks with the participation of social stakeholders.

It is emphasized that qualitative research is necessary to understand the relationship between experiences or interactions related to the social environment and psychiatric symptoms during adolescence [78]. Qualitative research involving focus groups includes inductive approaches that reveal the subjective experiences of individuals and the common qualities shared by the group through narrative and discourse analyses [98]. Among these qualitative approaches, Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), which originates from a theoretical, philosophical foundation, stands out as a comprehensive practical method that guides the emergence of individuals' processes in making sense of their subjective and social experiences [116, 117].

With the increasing prevalence and importance of online interviews in recent years, the Online Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (OIPA) method, which is based on IPA in analyzing the data obtained through Online Voice Photo (OPV), is frequently used in studies on youth [36, 119, 126]. Using the OIPA method, researchers aim to achieve effective results by revealing the experiences of youth related to their cultural identities at the micro, meso, exo, and macrosystem levels [127]. Therefore, there is a need for a comprehensive evaluation of the data we have obtained through qualitative studies to be conducted with Syrian refugee adolescents.

Limitations

This study has some limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the findings. Firstly, since the data collection process was conducted in a school setting, the findings cannot be generalized to adolescents who live in refugee camps, receive education in temporary educational institutions, or do not attend school. Secondly, measures of adolescent anxiety, life satisfaction, and peer relationships were only assessed through self-report measures. Self-report measures may be subject to response bias or social desirability bias. Therefore, the results may not replace direct assessments by mental health professionals, and caution should be exercised in interpreting the results.

Another limitation of this study is the Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient of our peer problem subscale, which yielded a lower-than-desired value. The fact that the Cronbach’s alpha value of the subscale in the Syrian sample was 0.40 poses a problem regarding scale reliability. However, in the Turkish sample, the Cronbach’s alpha value of the subscale was higher (0.70) than that in other studies. Since this subscale is known to be associated with loneliness and social desirability in adolescents, we obtained significant results in our study despite this limitation.

Lastly, the study design restricts the interpretation of the results regarding causal relationships. Although path analysis and moderation analysis were conducted to examine the relationships among variables and the moderating role of peer relationships, the study's cross-sectional design does not allow us to conclude the direction of the relationships or the causal effects of the variables on each other. Therefore, future studies should use longitudinal designs to establish temporal relationships among variables and examine causal relationships.

Data availability

Not applicable.

References

Abdallah T (1998) The satisfaction with life scale (SWLS): psychometric properties in an Arabic-speaking sample. Int J Adolesc Youth 7(2):113–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.1998.9747816

Aiken LS, West SG (2001) Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Sage, Newbury Park

Al-Masri F, Müller M, Nebl J, Greupner T, Hahn A, Straka D (2021) Quality of life among Syrian refugees in Germany: a cross-sectional pilot study. Arch Pub Health 79(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-021-00745-7

Al-Shatanawi TN, Khader Y, Alsalamat H, Al Hadid L, Jarboua A, Amarneh B, Alrabadi N (2023) Identifying psychosocial problems, needs, and coping mechanisms of adolescent Syrian refugees in Jordan. Front Psych 14:1057. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1184098

Apak H, Acar MC (2020) Analyzing the developmental problems experienced by Syrian adolescent refugees in terms of certain demographic variables. J Human Soc 10(2):65–94. https://doi.org/10.12658/m0333

Attanayake V, McKay R, Joffres M, Singh S, Burkle F, Mills E (2009) Prevalence of mental disorders among children exposed to war: a systematic review of 7,920 children. Med Confl Surviv 25(1):4–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13623690802568913

Avçin E, Erkoç B (2021) Covid-19 pandemi sürecinde sağlık anksiyetesi, yaşam doyumu ve ilişkili değişkenler. Tıbbi Sosyal Hizmet Dergisi 17:1–13. https://doi.org/10.46218/tshd.898389

Aziz S, Tariq N (2019) Depression, anxiety, and stress in relation to life satisfaction and academic performance of adolescents. Pak J Physiol 15(1):52–55

Baysu G, Phalet K, Brown R (2014) Relative group size and minority school success: the role of intergroup friendship and discrimination experiences. Br J Soc Psychol 53(2):328–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12035

Bean TM, Eurelings-Bontekoe E, Spinhoven P (2007) Course and predictors of mental health of unaccompanied refugee minors in the Netherlands: one-year follow-up. Soc Sci Med 64(6):1204–1215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.010

Becker K, Reiser M, Lambert S, Covello C (2014) Photovoice: conducting community-based participatory research and advocacy in mental health. J Creat Ment Health 9(2):188–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2014.890088

Beißert H, Mulvey KL (2022) Inclusion of refugee peers–differences between own preferences and expectations of the peer group. Front Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.855171

Betancourt TS, Newnham EA, Layne CM, Kim S, Steinberg AM, Ellis H, Birman D (2012) Trauma history and psychopathology in war-affected refugee children referred for trauma-related mental health services in the United States. J Trauma Stress 25(6):682–690. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21749

Betancourt TS, Abdi S, Ito BS, Lilienthal GM, Agalab N, Ellis H (2015) We left one war and came to another: resource loss, acculturative stress, and caregiver–child relationships in Somali refugee families. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 21(1):114

Bhugra D, Gupta S, Schouler-Ocak M, Graeff-Calliess I, Deakin NA, Qureshi A et al (2014) EPA guidance mental health care of migrants. Eur Psychiatry 29(2):107–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2014.01.003

Birmaher B, Brent DA, Chiappetta L, Bridge J, Monga S, Baugher M (1999) Psychometric properties of the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): a replication study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 38(10):1230–1236. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199910000-00011

Blackmore R, Gray KM, Boyle JA, Fazel M, Ranasinha S, Fitzgerald G, Misso M, Gibson-Helm M (2020) Systematic review and meta-analysis: the prevalence of mental illness in child and adolescent refugees and asylum seekers. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 59(6):705–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2019.11.011

Bogic M, Njoku A, Priebe S (2015) Long-term mental health of war-refugees: a systematic literature review. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 15(1):1–41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-015-0064-9

Bollmer JM, Milich R, Harris MJ, Maras MA (2005) A friend in need: the role of friendship quality as a protective factor in peer victimization and bullying. J Interpers Violence 20(6):701–712. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260504272897

Braun-Lewensohn O, Al-Sayed K (2018) Syrian adolescent refugees: How do they cope during their stay in refugee camps? Front Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01258

Brent DA, Silverstein M (2013) Shedding light on the long shadow of childhood adversity. J Am Med Assoc 309(17):1777–1778. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.4220

Bronfenbrenner U (1977) Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am Psychol 32(7):513–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

Bryman A, Cramer D (2004) Quantitative data analysis with SPSS 12 and 13: a Guide for Social Scientists, 1st edn, Routledge

Cakmakci FK (2004) Validity and reliability study of the screening for anxiety disorders in children [unpublished specialty thesis, Kocaeli University Faculty of Medicine]

Cartwright-Hatton S, Ewing D, Dash S, Hughes Z, Thompson EJ, Hazell CM, Field AP, Startup H (2018) Preventing family transmission of anxiety: feasibility RCT of a brief intervention for parents. Br J Clin Psychol 57(3):351–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12177

Chen XC, Wu Y, Ban CX, Wang Y, Zhang J, Fang Y (2014) Investigation and influence factors of anxiety of junior high school students in Jiading district of Shanghai. J Shanghaı Jıaotong Unıv 34(4):442. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1674-8115.2014.04.008

Choukas-Bradley S, Prinstein MJ (2014) Peer relationships and the development of psychopathology. In: Lewis M, Rudolph KD (eds) Handbook of developmental psychopathology. Springer, US, pp 185–204

Cohen J, Cohen P (1983) Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. NJ Eribaum, Hillsdale

Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS (2013) Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge

Cole E (1998) Immigrant and refugee children: challenges and opportunities for education and mental health services. Can J Sch Psychol 14(1):36–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/082957359801400104

Correa-Velez I, Gifford SM, Barnett AG (2010) Longing to belong: social inclusion and wellbeing among youth with refugee backgrounds in the first three years in Melbourne. Austr Soc Sci Med 71(8):1399–1408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.018

Çeri V, Nasiroğlu S (2018) The number of war-related traumatic events is associated with increased behavioural but not emotional problems among Syrian refugee children years after resettlement. Arch Clin Psychiatry 45:100–105. https://doi.org/10.1590/0101-60830000000167

Das JK, Salam RA, Lassi ZS, Khan MN, Mahmood W, Patel V, Bhutta ZA (2016) Interventions for adolescent mental health: an overview of systematic reviews. J Adolesc Health 59(2):S49–S60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.020

Dari T, Chan CD, Del Re J (2021) Integrating culturally responsive group work in schools to foster the development of career aspirations among marginalized youth. J Special Group Work 46(1):75–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/01933922.2020.1856255

Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S (1985) The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess 49(1):71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Doyumğaç İ, Tanhan A, Kıymaz MS (2021) Understanding the most important facilitators and barriers for online education during COVID-19 through online photovoice methodology. Int J Higher Educ 10(1):166–190. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v10n1p166

El-Awad U, Fathi A, Vasileva M, Petermann F, Reinelt T (2021) Acculturation orientations and mental health when facing post-migration stress: differences between unaccompanied and accompanied male Middle Eastern refugee adolescents, first- and second-generation immigrant and native peers in Germany. Int J Intercult Relat 82:232–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2021.04.002

Ellis BH, MacDonald HZ, Lincoln AK, Cabral HJ (2008) Mental health of Somali adolescent refugees: The role of trauma, stress, and perceived discrimination. J Consult Clin Psychol 76(2):184. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.184

Elmore AL, Crouch E (2020) The association of adverse childhood experiences with anxiety and depression for children and youth, 8 to 17 years of age. Acad Pediatr 20(5):600–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2020.02.012

Emam MM, Kazem AM, Al-Zubaidy AS (2016) Emotional and behavioural difficulties among middle school students in Oman: an examination of prevalence rate and gender differences. Emot Behav Diffic. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2016.1165965

Eruyar S, Maltby J, Vostanis P (2018) Mental health problems of Syrian refugee children: the role of parental factors. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27(4):401–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-1101-0

Essau CA, Lewinsohn PM, Olaya B, Seeley JR (2014) Anxiety disorders in adolescents and psychosocial outcomes at age 30. J Affect Disord 163:125–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.12.033

Eurostat (2023) First ınstance decisions on applications by citizenship, age, and sex - annual aggregated data (Rounded). Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/MIGR_ASYDCFSTA__custom_1497203/bookmark/table?lang=en&bookmarkId=062d9510-98db-4fc8-9e30-e07b3d30ae79. Accessed May 15, 2023

Fangen K (2006) Humiliation experienced by Somali refugees in Norway. J Refug Stud 19(1):69–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fej001

Fazel M, Wheeler J, Danesh J (2005) Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: a systematic review. The lancet 365(9467):1309–1314. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61027-6

Fazel M (2015) A moment of change: facilitating refugee children’s mental health in UK schools. Int J Educ Dev 41:255–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2014.12.006

Fazel M, Betancourt TS (2018) Preventive mental health interventions for refugee children and adolescents in high-income settings. Lancet Child Adoles Health 2(2):121–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2352-4642(17)30147-5

Filler T, Georgiades K, Khanlou N, Wahoush O (2021) Understanding mental health and identity from Syrian refugee adolescents’ perspectives. Int J Ment Heal Addict 19:764–777. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00185-z

General Directorate of Migration Management (2023) Annual Report T.C. Ministry of Interior, Directorate General of Migration Management: Ankara. Available online at: https://en.goc.gov.tr/temporary-protection27. Accessed 15 May 2023

George D (2011) SPSS for windows step by step: a simple study guide and reference, 17.0 update, 10/e. Pearson Education India

Goodman R (1997) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38(5):581–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

Gormez V, Kılıç HN, Orengul AC, Demir MN, Mert EB, Makhlouta B, Kınık K, Semerci B (2018) Evaluation of a school-based, teacher-delivered psychological intervention group program for trauma-affected Syrian refugee children in Istanbul, Turkey. Psychiatry Clin Psychopharmacol 27(2):125–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750573.2017.1304748

Güvenir T, Özbek A, Baykara B, Arkar H, Sentürk B, Incekas S (2008) Properties of the Turkish version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ). Turk J Child Adoles Mental Health 15(2):65–74

Hariz N, Bawab S, Atwi M, Tavitian L, Zeinoun P, Khani M, Birmaher B, Nahas Z, Maalouf FT (2013) Reliability and validity of the Arabic screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED) in a clinical sample. Psychiatry Res 209(2):222–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.12.002

Hasanović M (2012) Neuroticism and posttraumatic stress disorder in Bosnian internally displaced and refugee adolescents from three different regions after the 1992–1995 Bosnia-Herzegovina war. Paediatr Today 8(2):100–113. https://doi.org/10.5457/p2005-114.45

Havewala M, Felton JW, Lejuez CW (2019) Friendship quality moderates the relation between maternal anxiety and trajectories of adolescent internalizing symptoms. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 41(3):495–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-019-09742-1

Henley J, Robinson J (2011) Mental health issues among refugee children and adolescents. Clin Psychol 15(2):51–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9552.2011.00024.x

Hodes M, Vostanis P (2019) Practitioner review: mental health problems of refugee children and adolescents and their management. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 60(7):716–731. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13002

Hoe SL (2008) Issues and procedures in adopting structural equation modelling technique. J Appl Quant Methods 3(1):76–83

Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB (2010) Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med 7(7):1549–1676. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

Hyman I, Vu N, Beiser M (2000) Post-migration stresses among Southeast Asian refugee youth in Canada: a research note. J Comp Fam Stud 31(2):281–293. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.31.2.281

Ingleby D (2010) Forced migration and mental health: Rethinking the care of refugees and displaced persons. Springer, Berlin

Işiktaş S, Özsat K, Lesinger FY (2022) Covid-19 pandemi sürecinde bireylerin anksiyete ve yaşam doyumu düzeylerinin İncelenmesi. Uluslararası Türk Kültür Coğrafyasında Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi 7(1):65–75. https://doi.org/10.55107/turksosbilder.1107012

Javanbakht A, Rosenberg D, Haddad L, Arfken CL (2018) Mental health in Syrian refugee children resettling in the United States: war trauma, migration, and the role of parental stress. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 57(3):209–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.01.013

Kan ML, McHale SM (2007) Clusters and correlates of experiences with parents and peers in early adolescence. J Res Adolesc 17(3):565–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00535.x

Kandemir H, Karataş H, Çeri V, Solmaz F, Kandemir SB, Solmaz A (2018) Prevalence of war-related adverse events, depression and anxiety among Syrian refugee children settled in Turkey. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27(11):1513–1517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1178-0

Kermen U, Tosun Nİ, Doğan U (2016) Yaşam doyumu ve psikolojik iyi oluşun yordayıcısı olarak sosyal kaygı. Eğitim Kuram ve Uygulama Araştırmaları Dergisi 2(1):20–29

Khader Y, Bsoul M, Assoboh L, Al-Bsoul M, Al-Akour N (2021) Depression and anxiety and their associated factors among Jordanian adolescents and Syrian adolescent refugees. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 59(6):23–30. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20210322-03

Khamis V (2019) Posttraumatic stress disorder and emotion dysregulation among Syrian refugee children and adolescents resettled in Lebanon and Jordan. Child Abuse Negl 89:29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.12.013

Khesht-Masjedi MF, Shokrgozar S, Abdollahi E, Habibi B, Asghari T, Ofoghi R, Pazhooman S (2019) The relationship between gender, age, anxiety, depression, and academic achievement among teenagers. J Fam Med Primary Care 8(3):799. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_103_18

Kia-Keating M, Ellis BH (2007) Belonging and connection to school in resettlement: young refugees, school belonging, and psychosocial adjustment. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 12(1):29–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104507071052

Kneer J, Van Eldik AK, Jansz J, Eischeid S, Usta M (2019) With a little help from my friends: Peer coaching for refugee adolescents and the role of social media. Media Commun 7(2):264–274. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v7i2.1876

Kornbrot D (2014) Point biserial correlation. Statistics Reference Online, Wiley StatsRef

Köker S (1991) Normal ve sorunlu ergenlerin yaşam doyumu düzeyinin karşılaştırılması [Master's thesis, Ankara University/School of Social Sciences]

La Greca AM, Harrison HM (2005) Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: Do they predict social anxiety and depression? J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 34(1):49–61. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5

Lamkaddem M, Stronks K, Devillé WD, Olff M, Gerritsen AA, Essink-Bot ML (2014) Course of post-traumatic stress disorder and health care utilisation among resettled refugees in the Netherlands. BMC Psychiatry 14(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-90

Larsen JL (2010) Resilience building prevention programs. In: Clauss-Ehlers CS (ed) Encyclopedia of cross-cultural school psychology. Springer, pp 816–820

Lefèvre H, Moro MR, Lachal J (2019) Research in adolescent healthcare: the value of qualitative methods. Archives de Pédiatrie 26(7):426–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcped.2019.09.012

Lehnung M, Shapiro E, Schreiber M, Hofmann A (2017) Evaluating the EMDR Group traumatic episode protocol with refugees: a field study. J EMDR Pract Res 11(3):129–138. https://doi.org/10.1891/1933-3196.11.3.129

Li SS, Liddell BJ, Nickerson A (2016) The relationship between post-migration stress and psychological disorders in refugees and asylum seekers. Curr Psychiatry Rep 18:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-016-0723-0

Liebkind K, Jasinskaja-Lahti I (2000) Acculturation and psychological well-being among immigrant adolescents in Finland: a comparative study of adolescents from different cultural backgrounds. J Adolesc Res 15(4):446–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558400154002

Mahmoud JSR, Staten RT, Hall LA, Lennie TA (2012) The relationship among young adult college students’ depression, anxiety, stress, demographics, life satisfaction, and coping styles. Issues Ment Health Nurs 33(3):149–156. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2011.632708

Mann G (2010) ‘Finding a life’among undocumented Congolese refugee children in Tanzania. Child Soc 24(4):261–270

Marie M, SaadAdeen S, Battat M (2020) Anxiety disorders and PTSD in Palestine: a literature review. BMC Psychiatry 20(1):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02911-7

McDougall P, Vaillancourt T (2015) Long-term adult outcomes of peer victimization in childhood and adolescence: pathways to adjustment and maladjustment. Am Psychol 70(4):300–310. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039174

Measham T, Guzder J, Rousseau C, Pacione L, Blais-McPherson M, Nadeau L (2014) Refugee children and their families: supporting psychological well-being and positive adaptation following migration. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 44(7):208–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2014.03.005

Mels C, Derluyn I, Broekaert E (2008) Social support in unaccompanied asylum-seeking boys: a case study. Child Care Health Dev 34(6):757–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00883.x

Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Benjet C, Georgiades K, Swendsen J (2010) Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the national comorbidity survey replication–adolescent supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adoles Psychiatry 49(10):980–989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017

Motti-Stefanidi F, Pavlopoulos V, Obradović J, Masten AS (2008) Acculturation and adaptation of immigrant adolescents in Greek urban schools. Int J Psychol 43(1):45–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590701804412

Mukhaini AZ, Bekker HL, Cottrell D (2018) Describing psychological and behavioural problems in Omani young people: reliability of the self-reported Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) in Oman. J Child Adoles Health 2(2):19–23. https://doi.org/10.35841/child-health.2.2.19-23

Muller D, Judd CM, Yzerbyt VY (2005) When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. J Pers Soc Psychol 89(6):852

Mulvey KL, Hitti A, Rutland A, Abrams D, Killen M (2014) Context differences in children’s ingroup preferences. Dev Psychol 50(5):1507. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035593

Muthén L, Muthén B (2016) The comprehensive modelling program for applied researchers: user’s Guide, volume 5, Los Angeles

Narmandakh A, Roest AM, de Jonge P, Oldehinkel AJ (2021) Psychosocial and biological risk factors of anxiety disorders in adolescents: a TRAILS report. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 30(12):1969–1982. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01669-3

O’Keeffe GS, Clarke-Pearson K (2011) The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics 127(4):800–804. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-0054

Ortuño-Sierra J, Sebastián-Enesco C, Pérez-Albéniz A, Lucas-Molina B, Fonseca-Pedrero E (2022) Spanish normative data of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire in a community-based sample of adolescents: Datos normativos españoles del Cuestionario de capacidades y dificultades (SDQ) en una muestra comunitaria de adolescentes. Int J Clin Health Psychol 22(3):100328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2022.100328

Özer-Yürür Y, Komsuoğlu A, Ateşok Z (2016) Türkiye’deki suriyeli çocukların eğitimi: Sorunlar ve çözüm önerileri. Asos J 37:76–110. https://doi.org/10.16992/ASOS.11696

Palmer M, Larkin M, de Visser R, Fadden G (2010) Developing an interpretative phenomenological approach to focus group data. Qual Res Psychol 7(2):99–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780880802513194

Phinney JS, Ong AD (2002) Adolescent-parent disagreements and life satisfaction in families from Vietnamese-and European-American backgrounds. Int J Behav Dev 26(6):556–561. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250143000544

Pickering L, Hadwin JA, Kovshoff H (2020) The role of peers in the development of social anxiety in adolescent girls: a systematic review. Adoles Res Rev 5(4):341–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-019-00117-x

Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, Caye A, Rohde LA (2015) Annual research review: a meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 56(3):345–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12381

Priebe S, Giacco D, El-Nagib R (2016) Public health aspects of mental health among migrants and refugees: a review of the evidence on mental health care for refugees, asylum seekers and irregular migrants in the WHO European Region. World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe

Rizk Y, Hoteit R, Khater B, Naous J (2023) Psychosocial well-being and risky health behaviors among Syrian adolescent refugees in South Beirut: a study using the HEEADSSS interviewing framework. Front Psychol 14:1736. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1019269

Roest AM, de Vries YA, Lim CCW, Wittchen HU, Stein DJ, Adamowski T, Al-Hamzawi A, Bromet EJ, Viana MC, de Girolamo G, Demyttenaere K, Florescu S, Gureje O, Haro JM, Hu C, Karam EG, Caldas-de-Almeida JM, Kawakami N, Lepine JP, WHO World Mental Health Survey Collaborators (2019) A comparison of DSM-5 and DSM-IV agoraphobia in the world mental health surveys. Depress Anxiety 36(6):499–510. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22885

Rubin KH, Bukowski WM, Bowker JC (2015) Children in peer groups. In: Bornstein MH, Leventhal T, Lerner RM (eds) Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: ecological settings and processes. Wiley, pp 175–222

Rudolph KD (2014) Puberty as a developmental context of risk for psychopathology. In: Lewis M, Rudolph K (eds) Handbook of developmental psychopathology. Springer, pp 331–354

Salk RH, Hyde JS, Abramson LY (2017) Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychol Bull 143(8):783–822. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000102

Samara M, El Asam A, Khadaroo A, Hammuda S (2020) Examining the psychological well-being of refugee children and the role of friendship and bullying. Br J Educ Psychol 90(2):301–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12282

Scharpf F, Kaltenbach E, Nickerson A, Hecker T (2021) A systematic review of socio-ecological factors contributing to risk and protection of the mental health of refugee children and adolescents. Clin Psychol Rev 83:101930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101930

Scherer N, Hameed S, Acarturk C, Deniz G, Sheikhani A, Volkan S, Polack S (2020) Prevalence of common mental disorders among Syrian refugee children and adolescents in Sultanbeyli district, Istanbul: results of a population-based survey. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 29:e192. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796020001079

Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, Müller H (2003) Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol Res Online 8(2):23–74

Schwartz D, Ryjova Y, Kelleghan AR, Fritz H (2021) The refugee crisis and peer relationships during childhood and adolescence. J Appl Dev Psychol 74:101263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2021.101263

Sheskin DJ (2000) Handbook of parametric and nonparametric statistical procedures, 2nd edn. Chapman & Hall/CRC

Sierau S, Schneider E, Nesterko Y, Glaesmer H (2019) Alone, but protected? Effects of social support on mental health of unaccompanied refugee minors. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 28(6):769–780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1246-5

Sleijpen M, Haagen J, Mooren T, Kleber RJ (2016) Growing from experience: an exploratory study of posttraumatic growth in adolescent refugees. Eur J Psychotraumatol 7(1):28698. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v7.28698

Smith JA, Osborn M (2015) Interpretative phenomenological analysis as a useful methodology for research on the lived experience of pain. Br J Pain 9(1):41–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/2049463714541642

Smith JA (2019) Participants and researchers searching for meaning: conceptual developments for interpretative phenomenological analysis. Qual Res Psychol 16(2):166–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2018.1540648

Stein DJ, Lim CCW, Roest AM, de Jonge P, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Al-Hamzawi A, Alonso J, Benjet C, Bromet EJ, Bruffaerts R, de Girolamo G, Florescu S, Gureje O, Haro JM, Harris MG, He Y, Hinkov H, Horiguchi I, Hu C, Scott KM (2017) The cross-national epidemiology of social anxiety disorder: data from the world mental health survey initiative. BMC Med 15(1):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0889-2

Subasi Y (2023) College belonging among university students during COVID-19: an online interpretative phenomenological (OIPA) perspective. J Happiness Health 3(2):109–126. https://doi.org/10.47602/johah.v3i2.52

Sun J, Liang K, Chi X, Chen S (2021) Psychometric properties of the generalized anxiety disorder scale-7 item (GAD-7) in a large sample of Chinese adolescents. Healthcare 9(12):1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9121709

Sung YT, Chao TY, Tseng FL (2016) Reexamining the relationship between test anxiety and learning achievement: an individual-differences perspective. Contemp Educ Psychol 46:241–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.07.001

Szente J, Hoot J, Taylor D (2006) Responding to the special needs of refugee children: practical ideas for teachers. Early Childhood Educ J 34(1):15–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-006-0082-2

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS, Ullman JB (2013) Using multivariate statistics, vol 6. Pearson, Boston, pp 497–516

Tanhan A (2019) Acceptance and commitment therapy with ecological systems theory: addressing Muslim mental health issues and wellbeing. J Positive Psychol Wellbeing 3(2):197–219. https://doi.org/10.47602/jpsp.v3i2.172

Tanhan A, Francisco VT (2019) Muslims and mental health concerns: a social ecological model perspective. J Community Psychol 47(4):964–978. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22166

Tanhan A, Strack RW (2020) Online photovoice to explore and advocate for Muslim biopsychosocial spiritual wellbeing and issues: ecological systems theory and ally development. Curr Psychol 39(6):2010–2025. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00692-6

Tanhan A (2020) COVID-19 sürecinde online seslifoto (OSF) yöntemiyle biyopsikososyal manevi ve ekonomik meseleleri ve genel iyi oluş düzeyini ele almak: OSF’nin Türkçeye uyarlanması. [Utilizing online photovoice (OPV) methodology to address biopsychosocial spiritual economic issues and wellbeing during COVID-19: Adapting OPV to Turkish.] Turk Stud 15(4):1029–1086. https://doi.org/10.7827/TurkishStudies.44451

Teja Z, Schonert-Reichl KA (2013) Peer relations of chinese adolescent newcomers: relations of peer group integration and friendship quality to psychological and school adjustment. J Int Migr Integr 14:535–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-012-0253-5

Tuncer N (2017) Bir grup üniversite öğrencisinde belirlenen sosyal anksiyete düzeylerine göre bilinçli farkındalık ve yaşam doyumu düzeylerinin incelenmesi. Master's thesis, Işık University

Ullman C, Tatar M (2001) Psychological adjustment among Israeli adolescent immigrants: a report on life satisfaction, self-concept, and self-esteem. J Youth Adolesc 30:449–463. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010445200081

UNHCR (2018) Global Trends. Forced Displacement in 2018. Field Information and Coordination Support: Section Division of Programme Support and Management. Case Postale 2500 1211

Victor SE, Hipwell AE, Stepp SD, Scott LN (2019) Parent and peer relationships as longitudinal predictors of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury onset. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 13(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-018-0261-0

Virta E, Sam DL, Westin C (2004) Adolescents with Turkish background in Norway and Sweden: a comparative study of their psychological adaptation. Scand J Psychol 45(1):15–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2004.00374.x

Von Werthern M, Grigorakis G, Vizard E (2019) The mental health and wellbeing of Unaccompanied Refugee Minors (URMs). Child Abuse Negl 98:104146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104146

Vostanis P (2014) Meeting the mental health needs of refugees and asylum seekers. Br J Psychiatry 204(3):176–177. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.113.134742

Way N, Greene ML (2006) Trajectories of perceived friendship quality during adolescence: the patterns and contextual predictors. J Res Adolesc 16(2):293–320. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00133.x

Weinstein N, Khabbaz F, Legate N (2016) Enhancing need satisfaction to reduce psychological distress in Syrian refugees. J Consult Clin Psychol 84(7):645. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000095

Wentzel KR, Russell S, Baker S (2016) Emotional support and expectations from parents, teachers, and peers predict adolescent competence at school. J Educ Psychol 108(2):242–255. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000049

World Health Organization (2019) WHO global report on traditional and complementary medicine, 2019. World Health Organization

Yao S, Zhang C, Zhu X, Jing X, McWhinnie CM, Abela JR (2009) Measuring adolescent psychopathology: psychometric properties of the self-report strengths and difficulties questionnaire in a sample of Chinese adolescents. J Adoles Health 45(1):55–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.11.006

Yap MBH, Jorm AF (2015) Parental factors associated with childhood anxiety, depression, and internalizing problems: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 175:424–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.050

Yayan EH, Düken ME, Özdemir AA, Çelebioğlu A (2020) Mental health problems of syrian refugee children: post-traumatic stress, depression and anxiety. J Pediatr Nurs 51:27–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2019.06.012

Yetim O (2022) Examining the relationships between stressful life event, resilience, self-esteem, trauma, and psychiatric symptoms in Syrian migrant adolescents living in Turkey. Int J Adolesc Youth 27(1):221–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2022.2072749

Yetim Ü (1993) Life satisfaction: a study based on the organization of personal projects. Soc Indic Res 29(3):277–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01079516

Yilmaz R, Cikili Uytun M (2020) What do we know about bullying in syrian adolescent refugees? a cross sectional study from Turkey: (Bullying in Syrian Adolescent Refugees). Psychiatr Q 91(4):1395–1406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-020-09776-9

Yurtbay T, Alyanak B, Abali O, Kaynak N, Durukan M (2003) The psychological effects of forced emigration on Muslim Albanian children and adolescents. Community Ment Health J 39(3):203–212. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1023386122344

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to all the participants who generously shared their time and provided valuable insights for this study. We also extend our gratitude to the President and staff of the Freedom Schooner Association for their support in facilitating the data collection process.

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK). The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OY designed the study, participated in its design and coordination, drafted and developed the measures; RC designed, participated in its design and coordination, and drafted the study; EB performed statistical analysis and participated in the design and interpretation of data; ISA, contributed to data collection. All authors have read and approved the final article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The corresponding author declares that there is no conflict of interest on behalf of all authors.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the permission obtained from the ethics committee of a Toros University (2023/26).

Consent to participate

All participants completed an informed voluntary consent form.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yetim, O., Çakır, R., Bülbül, E. et al. Peer relationships, adolescent anxiety, and life satisfaction: a moderated mediation model in Turkish and syrian samples. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02366-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02366-7