Abstract

The purpose of this study was to complete the cycle of recognizing these relationships. In this regard, the effect of parenting styles, attachment styles, and the mediating variable of addiction was investigated on child abuse (CA). Multi-stage random sampling and sample size were selected based on the sample size estimation software (510 people) and according to the 20% probability of a drop in the number of subjects, 530 people (265 boys and 265 girls) and 1060 parents were selected. The available method was selected from a sample of 530 people who were selected based on the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) and answered Baumrind’s Parenting Styles Questionnaire (PSQ), Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), and Adult Attachment Scale (AAS). Data were assessed by analysis of variance, mediator analysis, and path analysis. The results showed that differences in parenting styles cause differences in their attachment styles. The results supported only the relationship between the two components of parental affection and control with the attachment avoidance index, and no relationship was observed between these components and the anxiety index. Perceived emotional abuse, mediates the relationship between parental parenting components and the child attachment avoidance index. Finally, it was achieved to a model that shows how the two factors of affection and control simultaneously affect the avoidance index, mediated by parental addiction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The worldwide problem of Child abuse (CA) has serious consequences and traumatic experiences. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), CA is any interaction that results in actual harm and is largely under the control of a strong or trusted parent or guardian (Lueger-Schuster et al., 2018). CA or child maltreatment means any kind of child mistreatment that is psychologically harmful based on social criteria and the opinion of experts; that is, any action that negatively affects the child’s behavioral, cognitive, physical, and emotional functioning; such as constant humiliation, neglect, insulting, beating, cursing the child and sexual molestation (Babakhanlou & Beattie, 2019). Evidence shows that different types of abuse are significantly related; therefore, when a person experiences a particular type of abuse, he or she is more likely to experience another type of abuse (Dorfman et al., 2018; Vrolijk-Bosschaart et al., 2019).

Early parent-child relationships (PCR) and traumatic childhood events play an important role in the formation of personality disorders. The PCR gives the child a framework for interacting with others (Quchani et al., 2021). Childhood traumas resulted from traumatic ACEs in childhood have short-term (physical (Vrolijk-Bosschaart et al., 2019) and psychosocial (Allen, 2017; Lewis et al., 2016; Vrolijk-Bosschaart et al., 2019) and long-term (psychiatric disorders such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, isolationism, and latent violence) consequences (Nesi et al., 2018; Righy et al., 2019; Vrolijk-Bosschaart et al., 2019; Haider et al., 2020). They have poor academic performance and have difficulty in social relationships (Alzahrani et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019). They are distrustful of others and, as a result, suffer from feelings of inferiority, inadequacy, negative self-concept, and failure (Babakhanlou & Beattie, 2019). During adolescence, they experience anti-social behaviors (delinquency), theft, running away from home, addiction, and running away from school (Zuquetto et al., 2019). In adulthood, they have prominent personality traits such as cowardice, misplaced bias, suspicion and pessimism, stereotypes, and obsessive behaviors (Mercer et al., 2017). Therefore it is important to evaluate CA in children in whom CA is suspected, merely to investigate whether it has a relationship with attachment styles, parenting styles, and parental addictions (Zuquetto et al., 2019). Correlates of CA include those associated with adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) such as child physical and/or sexual abuse (Kajeepeta et al., 2015), and having poor relationship quality with one’s mother (Quchani et al., 2021). In addition, several problem behaviors such as drug use (Stein et al., 2017), heavy drinking (Cunradi et al., 2020; Lee & Chen, 2017), and attachment anxiety (Erkoreka et al., 2021) are directly associated with CA.

One type of CA is emotional abuse. It is a repeated pattern of an attempt by parents to intimidate, control, or isolate another. Emotional abuse is done through acts such as insult and humiliation, intimidation, and verbal and behavioral aggression (Stark, 2015). In emotional abuse, the goal is the emotions and feelings of the individual and the body is not abused (Young & Widom, 2014). Methods of emotional abuse include tongue wounds, humiliation, blame, bitterness, and so on. Using emotional abuse, one’s values, values, self-confidence, self-concept, and self-esteem are targeted and destroyed (Yaffe, 2021; Yun et al., 2019). Symbolic violence is a type of emotional abuse and includes behaviors such as kicking walls, striking doors, and throwing away items (Stark, 2015). Emotional abuse during infancy is likely to erode a child’s sense of trust, and the development of healthy autonomy, and build healthy autonomy, and as a result may lead to problems developing self-esteem, self-worth, and strong feeling (Pinquart & Gerke, 2019). If this phenomenon occurs before the age of three, there are certain risks to developing attachment (Mak et al., 2020). Warmth and reciprocity are necessary for a baby to develop a secure attachment, and because the child’s parental relationship in cases of emotional abuse is not generally defined by these characteristics, such children are at risk of developing insecure attachment relationships (Liu, 2020). This position is problematic because abuse can be particularly damaging if it interferes with attachment security and emotional regulation tasks (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019). Quchani et al. (2021) compared two parenting training on improving the emotional-behavioral problems of the child with divorced single mothers and find both of them effective.

Parenting Style and Attachment

Baumrind’s theory of parenting style (1996) was implemented in this study to investigate the relationship between parenting CA based on attachment styles, parenting styles, and parental addictions (Zuquetto et al., 2019). It is the emotional bond the child develops with parents. Due to influence of attachment to parents on the individual’s life, it has attracted most interest (Becona et al., 2014; Berzenski, 2019; Quchani et al., 2021). Makariev and Shaver (2010), found a strong link between patterns of child attachment and those of maternal attachment.

Attachment affects parenting and views of self and their social development (Hoi Ching & Man Tak, 2017). Also, due to the high relation of attachment with parenting style, people’s worldview, and behavior outcome would be predictable. Attachment is an instinctual behavioral or biological stimulus system that ensures that the child and mother stay close together to ensure their security (Eman et al., 2017). In this regard, it is thought that attachment relationships in both children and adults are controlled by a single biological system (Mak et al., 2020). A secure attachment provides a platform for attachment profiles or caregivers to act as a secure haven for children to explore and learn about (Chang et al., 2015). These early ACEs of attachment influence the development of internal functional models. Models that will influence future perceptions, attitudes, and interpersonal ACEs are in fact complex schemas that include the emotional, defensive, and descriptive cognitive components associated with their aspects, attachment index, and attachment interactions (Chen, 2019). At home, the child becomes acquainted with the social philosophy of society and social relations (Kuppens & Ceulemans, 2019; Vrolijk-Bosschaart et al., 2019).

In normal parents, there are characteristics such as sharing and accompanying to set healthy parenting goals and providing for their interests, following rational methods in all family affairs, involving all family members in family-related decisions, and division of labor and responsibilities among family members, and also there is an opportunity for children to comment in the family environment (Fan & Chen, 2020). Under these conditions, the child’s development in different aspects of personality is better provided (Jaffee, 2017). The parenting system is of great importance as the first focal point in which a person is placed (Lizano & Mor Barak, 2015). One of the factors influencing the formation of a person’s character and mental health is the person’s parents or guardians (Nesi et al., 2018). The family environment is the first and most enduring factor that affects the development of human personality (Orth, 2018). In general, the attitude and behavior of parents in parenting can facilitate or hinder the growth and development of the child (Quchani et al., 2021). The position of the child in the family, the number and gender of children, the order of their birth, the relationship between them, the existence of correct moral and doctrinal values and criteria, the presence of other family members at home, relationships with peers and local children and factors such as economic and cultural factors shape child’s personality, along with his/her natural talent (Fan & Chen, 2020).

Parents are the founders of an important part of children’s destiny and play a major role in determining the future lifestyle, morals, health, and performance of the individual in the future (Bi et al., 2018). There are factors such as parents ‘personality, mental and physical health, educational methods applied to children, parents’ job and education, family economic and cultural status, family residence, family size and population, family social relations, and many other variables in the family those that affect a child’s personality, mental and physical health, career, educational, economic, social and cultural adjustment, family formation, etc. (Berzenski, 2019; Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2014). It is clear that if the parents are not competent enough, the children will be harmed and after entering the society and social interaction with others, they will spread their disease to others and destroy the structure of the society (Jozefiak & Sønnichsen Kayed, 2015). In the field of parenting styles, parents also harm children’s personalities through methods such as constant affection, over-domination, over-protection, and over-compassion (Masud et al., 2019). To achieve a healthy family, parents must pay attention to their children, take enough time for them and their normal needs, be honest with them, and avoid insulting, blaming, and punishing them (Julian et al., 2017). Considering the effects of CA on children’s health and its long-term effects on adulthood that threaten mental health, it is necessary to conduct research in this field and study its effective factors and various dimensions (Calders et al., 2020). There is also little research in this area that the results of the present study can pave the way for further research and its results can be used in counseling centers and families (Jaffee, 2017). In this regard, the rules of interpersonal interactions that help individuals to predict the behavior of others, are also included in these schemas (Newman & Newman, 2020). In the early years of life, these functional models are thought to be flexible and open to change (Masud et al., 2019). However, once these functional models are formed and stabilized once in their structure, they will show a relatively stable state throughout life. Thus, functional models in adulthood direct one’s interactions with others (Chen, 2019). Research over the last twenty years has supported the stability of attachment styles over time (Berzenski, 2019). In addition, hypotheses about adult attachment styles are based on evidence from childhood (Unger & De Luca, 2014). Children internalize information gained from various situations and interactions with caregivers, which shapes the nature of their relationships in adulthood (Julian et al., 2017).

Parenting is a special behavior that a parent chooses to use in caring for, nurturing, and educating their child. Attachment and affection systems are usually activated simultaneously (Doinita & Maria, 2015). In different cultures, secure infants and children have caregivers who are sensitive to their children’s symptoms and are consistently available to respond to them (Kerns & Brumariu, 2014). Caregivers of insecure infants and children are often unavailable, or behave in a repulsive and unkind manner (Jaffee, 2017). Factor analysis studies have identified two main dimensions in parenting. The first dimension can be described as “affection”. Affection refers to behaviors related to acceptance, warmth, and intimacy, and in contrast to rejection and criticism. The second dimension, called “control,” refers to parental control, support, and the promotion of autonomy (Calders et al., 2020). It has also been stated that parental acceptance and warmth are associated with the security of children’s attachment. Students who were victims of verbal, physical, and sexual abuse were more likely than their unhappy counterparts to use physical abuse and violence in their intimate relationships (Findley et al., 2015). These relationship disorders indicate the possibility of insecure attachment styles in abused individuals. Childs with secure attachment has relationships of higher quality in adulthood than those with insecure attachment (Lee et al., 2009). Those with insecure attachment styles often have more difficulty managing conflict with their friends (Newman & Newman, 2020). Insecure attachment adolescents perceived their parents as emotionally colder, more rejecting, and more supportive than secure attachments (Muris et al., 2003). In addition, research has shown that insecure attachment styles have been effective in people’s tendency to use drugs and can be one of the fundamental reasons for people to turn to drugs (Schindler, 2019). This can be justified by the fact that when a child finds his parents careless or rejecting, he becomes distrustful of the world around him and considers it unsafe. This causes the person to decompose psychologically and reduces their resilience to stress, and causes them to use ineffective coping strategies in stressful situations, and to use drugs to escape difficult situations (Findley et al., 2015). This intensifies while the person does not see a supportive and compassionate person around him and finds himself alone. Also, substance abusers often break up because they do not have a strong attachment relationship (Masud et al., 2019). Allen (2017) found that attachment security in adolescents was highly dependent on the functions of the mother-adolescent relationship and was specifically related to mother-adolescent coordination and mother support. Parenting styles include two main dimensions: Control is the level of strictness of the rules and what parents expect from their children (Calders et al., 2020). Affection and acceptance also include the intimacy, affection, kindness, and affection between parents and child (Table 1). Baumrind (1996) categorized parenting styles based on two indicators: demandingness and responsiveness. The identified three parenting styles include authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive typologies (Baumrind, 1996).

Parental parenting styles affect children’s personalities (Pellerin, 2005). Authoritative parenting styles result in a child with low levels of risky behaviors as well as high levels of adjustment, study skills, and academic performance (Abar et al., 2009; McKinney & Renk, 2008). In the permissive parenting style, children with low self-esteem and low attachment to parents, act as impulsive decisions and immaturity (Shahsavari, 2012). It can affect the control processes directly and CA indirectly (Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2009). Children with abusive or neglectful caregivers feel unworthy and consider people trustworthy. So they develop a negative working model of others and self. Children with responsive caregivers feel worthy and loveable and consider people as dependable. So they develop a positive working model of others and self (Bcheraoui et al., 2012). Based on working models of self and others, Conrad et al. (2021) identified four different attachment styles includes secure, preoccupied, fearful, and dismissing. Theorists argue that the experience of abuse affects children’s internal functioning patterns and, consequently, the child’s relationship with others (Finzi et al., 2001; Masud et al., 2019). The results of a study by Baer and Martinez (2006) show that children who have been abused are more likely to have insecure attachments than those in the control group. They also pointed out that the extent of the impact of different abuses on a child’s attachment varies. There is a positive association between attachment avoidance and CA, especially when the attachment styles of parents are mismatched (Doumas et al., 2008). Abnormal patterns of attachment in children, despite severe parenting problems, psychological trauma, or personal problems, have been associated with caregivers. For example, parents with a history of CA or neglect were more likely than their peers to have children with insecure attachment styles (Conrad et al., 2021). It has also been suggested that abnormal attachment patterns are associated with caregivers’ depression and addiction. In permissive parenting, children with low self-esteem and low attachment to parents, act as impulsive decisions and immaturity (Shahsavari, 2012).

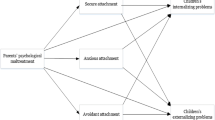

In a longitudinal study, adolescents who were victims of parental abuse reported significantly lower levels of parental attachment than adolescents who were not abused, and even those who witnessed only physical abuse between their parents (Julian et al., 2017). Unger and De Luca (2014) found that a history of physical abuse was associated with avoidant attachment. Many studies have examined the relationship between parental attachment and child attachment as well as parental attachment to their parenting styles (Millings et al., 2012). Insecure parents, for example, have had insecure children (Roelofs et al., 2008). On the other hand, insecure attachment parents chose authoritarian and affectionless parenting styles to raise their children, while secure attachment parents tended to authoritarian parenting styles (Doinita & Maria, 2015). According to these results, the transmission of attachment styles between generations can be observed (Curran et al., 2019). In the field of intergenerational attachment theories, which refer to the transmission of attachment styles from one generation to the next, Bowlby (1988) emphasizes the role of social effects as much as genetic influences and even more. The mechanisms by which this intergenerational transmission takes place in a social context are not completely clear (Curran et al., 2019; Roelofs et al., 2008). Sensitive responsiveness of the caregiver to the child is hypothesized to be one of these mechanisms (Masud et al., 2019). Insecure parents raise insecure children who will also be insecure parents in the future. Because of the solidarity between variables, a flowchart was designed. Figure. 1 presents the framework of the relationships between the variables in the current research.

Research framework (Huntsinger & Luecken, 2004)

The results show that the attachment of parents and their children are related. Researches have demonstrated that some psychological constructs such as parenting style (Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2009) and attachment style (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019) may be associated with addiction. This link may be mediated by the construct of addiction susceptibility (Hiroi & Agatsuma, 2005; Zuquetto et al., 2019). Most studies have examined parents’ attachment and parenting styles. But the issue that is less mentioned is the relationship between parents’ parenting style and the formation of attachment in their children. It is a topic that can complete the intergenerational cycle of attachment styles. In the present study, the effect of parenting styles, parental attachment style, and their addiction on CA was investigated. To make this connection more specific, the harms of CA by individuals have also been measured. The hypotheses of this study were presented as follows: parental attachment style causes a difference in their parenting style and consequently CA. Specifically, parents with low affection, or over control, are associated with insecure attachment styles in parents. On the other hand, it was hypothesized that parental addiction is related to parenting style and parental attachment style.

Methods and Materials

The present study is a causal-comparative (Ex-Post Facto) research with a causal design, which was conducted to investigate the effect of parenting styles, attachment styles, and parental addiction on the child.

Participants

In this causal-comparative (Ex-Post Facto) research with causal design, 175 people including children aged 13 to 15 years of high school in Mashhad and their parents in the academic year 2017–2019, which amounted to 85,842 people. Multi-stage random sampling and sample size were selected based on the sample size estimation software (510 people) and according to the 20% probability of a drop in the number of subjects, 530 people (265 boys and 265 girls) and 1060 parents were selected. In the present study, the available method was selected from a sample of 530 people who were selected based on the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) and answered the Baumrind Parenting Styles Questionnaire (PSQ), Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), and Adult Attachment Scale (AAS).

The sample consists of 175 students (81 boys and 94 girls), who were obtained by the available sampling method. The demographic information related to the sample is presented in Table 2.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria: (i) a minimum and maximum 15–18 years of age, (ii) not receiving any similar training services before or during the program, (iii) No symptoms of severe mental illness, and (iv) satisfaction with participating in the program.

Exclusion criteria: (i) reluctance to continue the program, (ii) Having severe physical illnesses (symptoms of coronary heart disease due to the prevalence of COVID-19 virus) that prevent adolescents from attending and cooperating, and (iii) unpredictable problems that prevent the teen from continuing the program.

Ethical Considerations

In this study, ethical standards including obtaining informed consent, guaranteeing privacy and confidentiality were observed. Consent was obtained from their parents for the children to participate in the test. Also, when completing the questionnaires, while emphasizing the completion of all questions, participants were free to leave the research at any time and provide personal information. They were assured that the information would remain confidential, and this was fully complied with. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in this study. The control group did not receive any treatment, but to respect their participation and maintain ethics, they were given books on parenting at the end of the course. There were no explicitly stated exclusion criteria. After the administrative process, obtaining the license of the Ethics Committee of the Islamic Azad University of Mashhad Branch, the researchers obtained an official license from the management of counseling centers and presented it to the relevant authorities, and received the necessary permission to conduct the study.

Measurement

The measurements were translated into Persian and back-translated to English by bilingual researchers to check language equivalency.

-

a.

Baumrind Parenting Styles Questionnaire (PSQ; Baumrind, 1996)

The PSQ is a 30-item, parent-report questionnaire based on Baumrind’s (1996) conceptualization of Authoritarian, Authoritative, and Permissive parenting styles. This questionnaire measures parenting styles in three factors (Fernández & Dufey, 2015). Items No. 28, 24, 21, 19, 17, 14, 13, 10, 6, 1 are in a permissive manner and items No. 29, 2, 3, 7, 9, 12, 16, 16, 25, 26 is related to the authoritarian method and items No. 11,15, 20, 22, 23, 27, 30 are related to the authoritative method. For each item, a 5-point Likert-type scale (0 = completely agree, 1 = almost agree, 2 = do not sure, 3 = almost disagree, and 4 = completely disagree), was implemented with higher scores indicating more frequent use of the described behavior. Internal consistency reliabilities for the 3 scales are good to excellent (Monaghan et al., 2012). The reliability of subscales by test-retest for the current sample is also good: 0.72 for Authoritarian style, 0.83 for Authoritative, and 0.77 for Permissive.

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein David et al., 2003)

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF), is a 28-item self-report measure that was developed to provide a reliable, valid, and retrospective assessment of traumatic experiences of CA and neglect history in the home (Liebschutz et al., 2018). It asks questions about adolescents’ and adults’ traumatic experiences (ages 18–23) and is quantified on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never true, 2 = rarely true, 3 = sometimes true, 4 = often true, 5 = very often true). It is arranged according to five subscales: physical and emotional abuse, emotional neglect, sexual abuse, and physical neglect. Bernstein and Fink (1998) reported the reliability of different questionnaire factors with two methods of retesting and Cronbach’s alpha between 0.79 and 0.94. In CTQ-SF, there are five items for each of the clinical scales, which together with the three minimalizations/denial scale items include a total of 28 items (Bernstein David et al., 2003). In the present study, the CTQ-SF was used. Cronbach’s alpha in this study was obtained as follows: total childhood injuries, 0.88–0.91; Emotional abuse, 0.84–0.89; Physical abuse, 0.81–0.86; Sexual abuse, 0.93–0.95; Emotional neglect, 0.88–0.92; Physical neglect, 0.83–0.87 (Bernstein & Fink, 1998).

-

b.

Adult Attachment Scale (AAS; Collins, 1996)

The Revised Adult Attachment Scale (AAS) was developed by Collins (1996). This 18 items scale was scored on a 5 point Likert-type scale. It is based on the assumption that similarities in child-caregiver attachment styles can also be found in adulthood (Ripardo Teixeira et al., 2019). It consists of two parts. In the first part, the subject is presented with the original three prototypical descriptions, which express the individual’s feelings about comfort, closeness, and intimacy in relationships, and measures adult attachment styles named “Secure (S)”, “Anxious (Ax)” and “Avoidant (Av)”. In the first part, the 7-point Likert scoring method is performed from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. In the second part, the attachment style is determined based on one of the three descriptions provided in the first part. The scoring method is categorical, with a score of 1 showing avoidant attachment, a score of 2 indicating anxious attachment (ambivalent), and a score of 3 indicating secure attachment (Table 3).

Internal consistency reliabilities were reported through Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.72 for Anxiety, 0.75 for Depend, and 0.69 for Close (Collins, 1996). There are modest correlations between Close and Depend (r = 0.38), a weak correlation between Depend and Anxiety (−0.24), and no correlation between Close and Anxiety (r = −0.08) (Ripardo Teixeira et al., 2019).

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed by SPSS-23 and using ANOVA, mediator analysis, path analysis, and correlation calculation.

Results

The descriptive statistics presented in Table 4 provide detailed information about the sample and the scales used on them.

Table 5 also presents the calculated correlations. A Nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was employed to test the hypothesis that differences in parental attachment styles cause differences in parenting styles, using the nominal variables parenting (emotional restraint, insensitive control, optimal, procrastinating), and attachment (Secure, anxious, Dismissing Av, Fearful Av). The results of this test showed that people who have grown up under different attachment styles also have different parenting styles. In other words, differences in parental attachment styles have led to differences in parenting styles. Also, the addiction index has been effective as a mediating variable on CA. After obtaining this result, three stages of one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were performed between the subjects. At all stages of attachment styles (secure, anxious, dismissing avoidance, fearful-avoidant), they were intergroup variables, and the variables of over control, affection, and total abuse were replaced as dependent variables, respectively. The use of ANOVA in the first stage showed that there is a significant difference in the component of parental over-control between people who have different attachment styles (P = 0.012 and F3, 171 = 3.767). The LSD post hoc test showed that the over control component score was higher in both the fearful-avoidant and dismissing avoidance attachments than the secure attachments. However, there was no significant difference between secure and anxious attachments in the control component score. The use of ANOVA in the second stage showed that there is a significant difference in the component of parental affection between people who have different attachment styles. Thus, the score of the affection component in both fearful-avoidant and dismissing avoidance attachments is lower than secure attachments. Also, the score of dismissing avoidance attachments is lower than that of anxious attachments. The use of ANOVA in the third stage showed that there is a significant difference between people who have different attachment styles in the scale of CA or total abuse (whose score is the sum of scores in all types of abuses). Thus, there was no significant difference only between dismissing and fearful-avoidant attachments and secure attachments.

Multiple regression analysis (MRA) was performed to investigate the mediating role of parental addiction in the relationship between parenting components (authoritarian and permissive) with attachment system indicators (anxiety and avoidance). According to the two components of parenting and two indicators of attachment, four separate MRA were performed. In this way, first, the MRA was done for the total abuse scale, and only if it is significant, the subscales of child trauma were examined. The results of these analyzes are presented in Table 6.

Mediation analysis was performed using the bootstrap method with the bias-corrected method (MacKinnon et al., 2004). Indirect effects were investigated with a 95% confidence interval by 5000 samplings by the bootstrap method (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). The results of the mediator analysis show the mediating role of the specified variable. If the results show that the direct effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable is meaningless when controlling the mediator variable (here child injuries), it can be concluded that the variable in question played the role of complete mediator; Otherwise, that is, when a direct relationship is still significant with the control of the mediator variable, relative mediation is considered. The significance of each mediation model is summarized in Table 7. The model presented in Fig. 2 was obtained to predict the CA index by the components of parenting style (permissive and authoritarian), attachment styles, and parental addiction. This model was evaluated by SPSS Amos 23 software using chi-square test indices, Confirmatory Fit Index (CFI), the Normed Fit Index (NFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA).

Chi-square test was not significant (\({X}_{df=1,n=175}^2=45.1\)), which means that there is no difference between the proposed model and the obtained data. So, the observed data have a high similarity with this model. The goodness of fit indices including CFI and NFI had values of 0.997 and 0.992, respectively. RMSEA had values of 0.051, which indicates the goodness of fit index of the model with the obtained data. All path coefficients were statistically significant (P < 0.05). This model shows that the score of the components of parental attachment styles is influential in the index scores of parenting styles, ie permissive and authoritarian. Of course, the effect of the negligent factor is completely indirect and is exerted through addiction, while the mediation of parental addiction to the over control component is relative, and this major component exerts its effect directly on CA.

Discussion

In the present study, the relationship between attachment styles, parenting styles, and parental addiction and its impact on CA was investigated. The results of the correlation test showed that the permissive and authoritarian components of parents have a significant relationship with the avoidant attachment index in parents. In other words, increasing parental avoidant attachment has increased parental control or care, followed by CA. This result is consistent with many previous studies (Calders et al., 2020; Vrolijk-Bosschaart et al., 2019). However, the components of parenting were not significantly related to the attachment anxiety index in children. Similarly, in the studies of Finzi et al. (2001), Baer and Martinez (2006), and Unger and De Luca (2014), Fan and Chen (2020), CA was associated with the avoidance index but no association was found with the anxiety index. Their findings suggested a link between avoidant attachment in adulthood and a history of physical abuse in childhood but found no evidence to support a link between anxiety attachment and the history of CA. Therefore, it seems that childhood trauma records mainly affect the avoidance index.

Explaining this result, it can be inferred that parenting styles are the methods that parents use in dealing with their children and have a profound effect on their formation and development in childhood and their subsequent personality and behavioral characteristics. Attachment is an essential element of human evolution and attachment style is the process by which an emotional bond is formed in the mother-infant relationship, and the infant becomes emotionally attached to his or her parents. Authoritative parents have a high level of control and responsiveness. They see their children as competent and successful people and expect them according to their ability. These parents also respect their children’s personalities and their children are independent, warm, friendly, and have a more cooperative spirit. This is while the avoidant attachment style is in conflict with this style and is associated with low levels of intimacy and commitment. Parents of children with avoidant attachment styles are irresponsible towards their children, they tend to use corporal punishment and prevent interference in work, and this is why people with avoidant attachment styles feel inadequate and worthless. These people see themselves as self-sufficient, deny vulnerability, and claim that they do not need close relationships, and tend to avoid intimacy. According to the explanations given above, it seems natural that children of parents with authoritarian parenting styles in their attachment styles should not be avoided.

Regarding the effect of parental attachment styles on parenting styles, the results showed that differences in parental attachment styles cause differences in their parenting styles. In other words, the style of attachment and parental behavior form the model of CA. Then, analysis of variance and posthoc tests showed that people with different types of CA differed in the amount of control and affection (care) received from their parents. The prevalence of CA in parents with fearful avoidant, and dismissing avoidance attachments was higher and less than the level of secure attachments, respectively. This means that parental over-control or parental affectionless control can lead to CA. This finding is consistent with the results of a study by Muris et al. (2003), Calders et al. (2020), and Masud et al. (2019). In their study, abused children perceived their parents as rejecting, cold, and overly supportive. Roelofs et al. (2008) also reported that children who described themselves as abused by their fathers had fathers whose scores were lower than average on the scale of authoritative parenting. Our results did not show a difference in the over control component between secure and anxious attachment styles. In other words, there was no difference in the perceived control of secure and anxious attachments. In this study, the components of anxiety attachment also affected the parenting index.

In explaining this conclusion, it can be inferred that authoritative parents value both autonomous behavior and discipline because they believe that rational control, as well as calculated freedom, enable children to internalize the rules and principles of correct behavior. They feel responsible for their actions and behavior. In addition to being warm and loving, these parents lead their children to independence, thus providing a context in which the child feels valued. These traits are also characteristic of people with a secure attachment style who, in their own and others’ inner activation patterns, come to the cognitive conclusion that they are valuable and worth caring for and that others (here parents) are caring people. And will be accountable for being present when needed and meeting their needs. People with secure attachments are those who have a positive sense of self and a positive perception of others and are more socially confident and successful. According to the explanations given above, it seems natural that children of parents with authoritative parenting styles are safe in their attachment style.

Regarding the effect of parental addiction on the prevalence of CA, the results of ANOVA showed that is addiction is effective in the prevalence of CA, which is consistent with previous findings, including Finzi et al. (2001), Baer and Martinez (2006), and Yaffe (2021). Here, parents with avoidant attachments (fearful and dismissing) did more harm to their children than secure and anxious attachments. Moreover, there was no difference between secure attachments and anxious attachments. The secure-base phenomenon refers to the development of the child’s ability to explore the environment when in a secure relationship with his/her caregiver (Bowlby, 1988). In childhood, the child’s search and exploration are related to the material and physical environment, while in adolescence it focuses on emotional and cognitive independence from parents (Fan & Chen, 2020). Thus, according to the findings of this study, a secure base for adolescents is formed in a strong relationship with parents, while encouraging them to gain cognitive and emotional autonomy (Babakhanlou & Beattie, 2019). Since over-controlling parents do not allow their children to gain autonomy, it is obvious that the formation of a secure base in these children will be disrupted. Numerous indicators have been proposed for the phenomenon of the secure base in adolescents.

The effect of parental addiction on children is that addicted parents want their child to reach a level of maturity to take on responsibilities, and this is one of the effects of parental addiction on children. They violate growing up independently and turning their child into a professional caregiver who lacks social skills and a sense of personal identity. The stress of caring for addicted parents can impair children’s brain development. Children who live with their addicted parents are disturbed to provide for their emotional needs because the parents are unable to take on their responsibilities physically and mentally, thus putting these children at risk for social, psychological, and psychological harm.. As a result, they experience problems such as exposure to abuse, malnutrition, isolation, and exposure to crime, and unlike their friends, they cannot evolve. As a result, these children may become so distant from social life that they are unable to build constructive relationships with their peers.

Regarding the component of parental care, one can name “maternal sensitivity”, which is one of the security correlations of attachment in childhood. It includes a large part of the phenomenon of the secure base in adolescence (Mak et al., 2020). Another potential indicator is the adolescent’s deidealization of the parent (Main & Goldwyn, 1998). The ideal view of parents is thought to be the product of childhood black-and-white thinking. However, in adolescence, with the formation of operational thinking, this scene is replaced by a more critical, rational, and meticulous view (Fan & Chen, 2020; Yaffe, 2021). “Perceived emotional support” is considered as another component of adolescence’s haven (Julian et al., 2017).

Regarding the mediating role of parenting attachment styles and parenting styles, because the indicators of parenting attachment styles and parenting styles were related to both CA and the addiction index, so the mediation analyzes were conducted to clarify their relationship. The results showed that the emotional abuse subscale plays a mediating role both in the relationship between affection and avoidance index and in the relationship between over control and avoidance index. The difference is that mediation in the first relationship is complete and in the second relationship is relative. In other words, the components of parenting affect the avoidance index by causing emotional abuse in the child. A decrease in parental affection for the child leads to the perception that he/she has been abused by the parents and, as a result, avoids them. The same thing happens with the over-control component. It is believed that the avoidance strategy allows children to disable their intimate behaviors, thus avoiding the potentially dangerous consequences of approaching others (Mak et al., 2020). Crittenden and Ainsworth (1989) point to two distinct patterns of children’s response to physical abuse. One of the most common reactions of children to physical abuse is their extreme obedience to their parent’s wishes. This reaction reduces the likelihood of parental abuse but creates a belief in children that their value depends on the expectations of others, and also increases their vulnerability to lack of self-doubt when replacing others with others. The second type of these reactions is anger and acting out in front of the parents. This behavior increases the likelihood of parental abuse and related problems in the future. For example, the expectation of harm is learned from others and the person acts accordingly in adulthood. However, children who act out can create and maintain a sense of self that obedient children are unable to create (Julian et al., 2017; Yaffe, 2021). If we look at the sub-items of emotional abuse, for example, “My family members abused or insulted me”, or “I felt that someone in my family hated me”, we find that low parental affection or parental over control make such schemes in the child. According to attachment theory, this type of parental behavior will lead to the formation of negative models of self (I do not deserve love and support), and others (others are unreliable and rejecting) and the result is an insecure attachment in the child. In such situations, from a behavioral point of view, the child inactivates his/her intimacy behaviors and chooses to avoid them to avoid the undesirable consequences of being close to others (Julian et al., 2017). This in itself may reinforce the child’s schemas about themselves and others. Although the prediction coefficients related to these two mediation models are low (0.14), but these two models have good significance. The reason for this small coefficient can be attributed to the lack of control over the related modifier variables in this study. For example, in the area of abuse and attachment, social support is one of the important variables that has often been associated with positive outcomes in victims of abuse (Unger, 2004; Babakhanlou & Beattie, 2019). The child’s temperament can also affect attachment-related interactions (Sroufe, 1985; Yun et al., 2019; Yaffe, 2021). As a result, such a relationship is very likely in the proposed model, but further studies are needed.

In the final model, the relationship between all variables is examined. This model has shown the combination of low affection and over-control factors in creating an avoidance index, mediated by addiction (Fig. 2). In the mediation models mentioned earlier, the indicators of attachment and parenting styles were examined separately, but in this model, both permissive and authoritarian components were applied simultaneously. The resulted difference was that the mediation of emotional abuse was replaced by total abuse (which is the sum of all perceived abuse). In this regard, researchers in the field of CA have observed high correlations between different types of abuse, including physical abuse, sexual abuse, psychological abuse, or emotional abuse and neglect (Styron & Janoff-Bulman, 1997; Yun et al., 2019; Yaffe, 2021), and see emotional abuse as the basis of all abuse (Pinquart & Gerke, 2019; Quchani et al., 2021). As a result, previous findings remain valid. The proposed model shows that permissive and authoritarian, secure anxiety and avoidance indicators are effective in creating or activating the CA index at the same time. Of course, the effect of low parental affection is completely indirect and mediated by addiction, while the main effect of over control is high directly and directly affects the increase of CA index activity. Regarding the component of affectionless parenting, it can be said that low affection cannot affect the CA index as long as it does not lead to the perception of harm or abuse by the parents. Here the role of the child’s mood and his cognitive schemas will be highlighted. In this regard, further studies are recommended.

Conclusion

The results of the present study generally identified the relationship between attachment style indicators and parenting styles, addiction, and CA indicators, and clarified how this relationship. All results supported the effect of attachment styles, parenting styles, and parental addiction on CA. However, no association was found between these variables and the attachment anxiety index with CA. Anxiety attachments were not different from secure attachments in most scores. By considering the role of attachment styles and parenting styles, a favorable ground can be provided in preventive interventions and treatment programs to promote the physical and psychological health of individuals. The results of this study emphasize the need for warmth, love, and intimacy in the parent-child relationship in the form of high control, demandingness, and high responsiveness. It also endorses the authoritative parenting style that leads to the formation of a secure attachment style.

From a theoretical perspective, this paper provides a new vision for future research. As well, this study examined concepts such as the relation of parenting CA based on attachment styles, parenting styles, and parental addictions. Also, the results may advance more insight among parents about the importance of parenting CA based on attachment styles, parenting styles, and parental addictions, and the value of positive parenting style among children. Hence, the results from this research can promote awareness and boost interest for further identification of this issue. Conducting such research helps parents to become familiar with different parenting methods and their consequences, to correct their behavior, and to understand in dealing with their children. This research also helps counselors to develop skills training activities for parents in schools to develop students’ abilities and competencies. One of the strengths of this study is the use of male and female addicts. This increases the generalizability of research findings. Individual matching of experimental and control groups in terms of age, sex, and entry and exit criteria has increased the internal validity of this study.

Limitations

The major limitation of this study was the available sampling method and limited research sample to students and their parents which limits the generalization of results. Other limitations of this research include lack of separation of people with different social and economic bases, lack of honesty in responding to the background of CA of the studied sample. Also, we can point to the cross-sectional nature and lack of causal explanation between attachment styles and parenting styles.

Direction for Future Research

One of the possible options could be to study the larger community of these people or influential social variables. It is suggested that future research be conducted with more accurate sampling methods. Also, considering the relationship between social support and attachment, it seems necessary to measure and examine this variable. Since in this study we only measured the attachment styles and parenting styles and addictions of one parent, it is suggested that in future studies these components be measured and examined separately for both mother and father. The question that arises is what makes these people not have secure attachments and fall into the category of anxious attachments? Future studies will be responsible in this regard.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Abar, B., Carter, K. L., & Winsler, A. (2009). The effects of maternal parenting style and religious commitment on self-regulation, academic achievement, and risk behavior among African-American parochial college students. Journal of Adolescence, 32(2), 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.03.008

Aebi, M., Linhart, S., Thun-Hohenstein, L., Bessler, C., Steinhausen, H. C., & Plattner, B. (2015). Detained male adolescent Offender's emotional, physical and sexual maltreatment profiles and their associations to psychiatric disorders and criminal behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(5), 999–1009. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9961-y

Allen, B. (2017). Children with sexual behavior problems: Clinical characteristics and relationship to child maltreatment. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 48, 189–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-016-0633-8

Alzahrani, M., Alharbi, M., & Alodwani, A. (2019). The effect of social-emotional competence on children academic achievement and behavioral development. International Education Studies, 12(12), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v12n12p141

Babakhanlou, R., & Beattie, T. (2019). Child abuse. innovation: Education and inspiration for general practice, 12(4), 180–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/1755738018820872

Baer, J. C., & Martinez, C. D. (2006). Child maltreatment and insecure attachment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 24(3), 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646830600821231

Baumrind, D. (1996). The discipline controversy revisited. Family Relations, 45, 405–414.

Bcheraoui, C. E., Kouriye, H., & SAdib, S. M. (2012). Physical and verbal/emotional abuse of schoolchildren, Lebanon, 2009. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 18(10), 1011–1020. https://doi.org/10.26719/2012.18.10.1011

Becona, E. B., Fernández del Río, E., Calafat, A., & Fernández-Hermida, J. R. (2014). Attachment and substance use in adolescence: A review of conceptual and methodological aspects. Adicciones, 26(1), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.20882/adicciones.137

Bernstein, D. P., & Fink, L. (1998). Childhood trauma questionnaire: A retrospective self-report manual San Antonio. The Psychological Corporation.

Bernstein David, P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., et al. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0

Berzenski, S. (2019). Distinct emotion regulation skills explain psychopathology and problems in social relationships following childhood emotional abuse and neglect. Development and Psychopathology, 31(2), 483–496. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579418000020

Bi, X., Yang, Y., Li, H., Wang, M., Zhang, W., & Deater-Deckard, K. (2018). Parenting styles and parent–adolescent relationships: The mediating roles of behavioral autonomy and parental authority. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2187. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02187

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. Routledge.

Calders, F., Bijttebier, P., Bosmans, G., Ceulemans, E., Colpin, H., Goossens, L., Van Den Noortgate, W., Verschueren, K., & Van Leeuwen, K. (2020). Investigating the interplay between parenting dimensions and styles, and the association with adolescent outcomes. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 29, 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01349-x

Chang, F. C., Chen, P. H., Chiang, J. T., Chiu, C. H., Lee, C. M., Miao, N. F., & Pan, Y. C. (2015). The relationship between parental mediation and internet addiction among adolescents, and the association with cyberbullying and depression. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 57, 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.11.013

Chen, B. B. (2019). Chinese mothers’ sibling status, perceived supportive co-parenting, and their children’s sibling relationships. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 684–692. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-01322-3

Cleveland, H. H., Herrera, V. M., & Stuewig, J. (2003). Abusive males and abused females in adolescent relationships: Risk factor similarity and dissimilarity and the role of relationship seriousness. Journal of Family Violence, 18, 325–339. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026297515314

Collins, N. L., & Read, S. J. (1990). Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(4), 644–663.

Collins, N. L. (1996). Working models of attachment: Implications for explanation, emotion, and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 810–832. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.71.4.810

Conrad, R., Forstner, A.J., Chung, ML. et al. (2021). Significance of anger suppression and preoccupied attachment in social anxiety disorder: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry, 21, 116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03098-1.

Crittenden, P. M., & Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1989). Child maltreatment and attachment theory. In D. Cicchetti & V. Carlson (Eds.), Child maltreatment: Theory and research on the causes and consequences of child abuse and neglect (pp. 432–463). Cambridge University Press.

Cunradi, C. B., Caetano, R., Alter, H. J., & Ponicki, W. R. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences are associated with at-risk drinking, cannabis, and illicit drug use in females but not males: An emergency department study. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 46(6), 739–748. https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990.2020.1823989

Curran, T., Meter, D., Janovec, A., Brown, E., & Caban, S. (2019). Maternal adult attachment styles and mother-child transmissions of social skills and self-esteem. Journal of Family Studies, 27(4), 491–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2019.1637365

Doinita, N. E., & Maria, N. D. (2015). Attachment and parenting styles. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 203, 199–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.08.282

Dorfman, M. V., Metz, J. B., & Feldman, K. W. (2018). Oral injuries and occult harm in children evaluated for abuse. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 103, 747–752. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2017-313400

Doumas, D. M., Pearson, C. L., Elgin, J. E., & McKinley, L. L. (2008). Adult attachment as a risk factor for intimate partner violence: the “mispairing” of partners’ attachment styles. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23(5), 616–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260507313526

Eman, M. A. S., Fadel, A. H., & Abdel Aziz, M. T. (2017). The relation between parenting styles and attachment among preschool children in the Gaza strip. Global Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disabilities, 3(3), 100–111. https://doi.org/10.19080/GJIDD.2017.03.555619

Erkoreka, L., Zamalloa, I., Rodriguez, S., Muñoz, P., Mendizabal, I., Zamalloa, M.I., Arrue, A., Zumarraga, M., & Gonzalez-Torres, M.A. (2021). Attachment anxiety as a mediator of the relationship between childhood trauma and personality dysfunction in borderline personality disorder. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 6. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2640.

Fan, J., & Chen, B. B. (2020). Parenting styles and co-parenting in China: The role of parents and children’s sibling status. Current Psychology, 39, 1505–1512. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00379-7

Fernández, A. M., & Dufey, M. (2015). Adaptation of Collins’ revised adult attachment dimensional scale to the Chilean context. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 28(2), 242–252. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-7153.201528204

Findley, P. A., Plummer, S. B., & McMahon, S. (2015). Exploring the experiences of abuse of college students with disabilities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515581906

Finzi, R., Ram, A., Har-Even, D., & Shnit, D. (2001). Attachment styles and aggression in physically abused and neglected children. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 30, 769–786. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012237813771

Franziska Meinck, F., Fry, D., Ginindza, C., Wazny, K., Elizalde, A., Spreckelsen, T. F., Maternowska, M. C., & Dunne, M. P. (2017). Emotional abuse of girls in Swaziland: Prevalence, perpetrators, risk and protective factors and health outcomes. Journal of Global Health, 7(1), 010410. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.07.010410

Gerra, G., Leonardi, C., Cortese, E., Zaimovic, A., Dell'agnello, G., Manfredini, M., et al. (2009). Childhood neglect and parental care perception in cocaine addicts: Relation with psychiatric symptoms and biological correlates. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 33(4), 601–610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.08.002

Haider, I. I., Tiwana, F., & Tahir, S. M. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adult mental health. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 36(COVID19-S4), S90–S94. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2756

Hiroi, N., & Agatsuma, S. (2005). Genetic susceptibility to substance dependence. Journal of Molecular Psychiatry, 10, 336–344. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.mp.4001622

Hoi Ching, K. H., & Man Tak, L. (2017). The structural model in parenting style, attachment style, self-regulation and self-esteem for smartphone addiction. IAFOR Journal of Psychology & the Behavioral Sciences, 3(1), 85–103. https://doi.org/10.22492/ijpbs.3.1.06

Huntsinger, E. T., & Luecken, L. J. (2004). Attachment relationships and health behavior: The mediational role of self-esteem. Psychology & Health, 19(4), 515–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/0887044042000196728

Jaffee, S. R. (2017). Child maltreatment and risk for psychopathology in childhood and adulthood. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8(13), 525–551. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045005

Jozefiak, T., & Sønnichsen Kayed, N. (2015). Self- and proxy reports of quality of life among adolescents living in residential youth care compared to adolescents in the general population and mental health services. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 13(1), 104. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-015-0280-y

Julian, M., Lawler, J., & Rosenblum, K. (2017). Caregiver-child relationships in early childhood: Interventions to promote well-being and reduce risk for psychopathology. Current Behavioral Neuroscience Reports, 4, 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40473-017-0110-0

Kajeepeta, S., Gelaye, B., Jackson, C. L., & Williams, M. A. (2015). Adverse childhood experiences are associated with adult sleep disorders: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine, 16(3), 320–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2014.12.013

Kuppens, S., & Ceulemans, E. (2019). Parenting styles: A closer look at a well-known concept. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 168–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1242-x

Kerns, K. A., & Brumariu, L. E. (2014). Is insecure parent-child attachment a risk factor for the development of anxiety in childhood or adolescence? Child Development Perspectives, 8(1), 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12054

Lee, R. D., & Chen, J. (2017). Adverse childhood experiences, mental health, and excessive alcohol use: Examination of race/ethnicity and sex differences. Child Abuse & Neglect, 69, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.04.004

Lee, S., Juon, H. S., Martinez, G., Hsu, C. E., Robinson, E. S., Bawa, J., & Ma, G. X. (2009). Model minority at risk: Expressed needs of mental health by Asian American young adults. Journal of Community Health, 34(2), 144–152.

Lewis, T., McElroy, E., Harlaar, N., & Runyan, D. (2016). Does the impact of child sexual abuse differ from maltreated but non-sexually abused children? A prospective examination of the impact of child sexual abuse on internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. Child Abuse & Neglect, 51, 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.11.016

Liebschutz, J. M., Buchanan-Howland, K., Chen, C. A., Frank, D. A., Richardson, M. A., Heeren, T. C., Cabral, H. J., & Rose-Jacobs, R. (2018). Childhood trauma questionnaire (CTQ) correlations with prospective violence assessment in a longitudinal cohort. Psychological Assessment, 30(6), 841–845. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000549

Liu, X. (2020). Parenting styles and health risk behavior of left-behind children: The mediating effect of cognitive emotion regulation. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29, 676–685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01614-2

Lizano, E. L., & Mor Barak, M. (2015). Job burnout and affective wellbeing: A longitudinal study of burnout and job satisfaction among public child welfare workers. Children and Youth Services Review, 55, 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.05.005

Lueger-Schuster, B., Knefel, M., Glück, T. M., Jagsch, R., Kantor, V., & Weindl, D. (2018). Child abuse and neglect in institutional settings, cumulative lifetime traumatization, and psychopathological long-term correlate in adult survivors: The Vienna institutional abuse study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 76, 488–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.12.009

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4

Makariev, D. W., & Shaver, P. R. (2010). Attachment, parental incarceration, and possibilities for intervention: An overview. Attachment & Human Development, 12, 311–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/14751790903416939

Mak, M. C. K., Yin, L., Li, M., Cheung, R. Y., & Oon, P. T. (2020). The relation between parenting stress and child behavior problems: Negative parenting styles as mediator. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29, 2993–3003. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01785-3

Main, M., & Goldwyn, R. (1998). Adult attachment scoring and classification system. Unpublished Manual, University of California at Berkeley.

Masud, H., Ahmad, M. S., Cho, K. W., & Fakhr, Z. (2019). Parenting styles and aggression among Young adolescents: A systematic review of literature. Community Mental Health Journal, 55, 1015–1030. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-019-00400-0

McKinney, C., & Renk, K. (2008). Differential ParentingBetween mothers and fathers implications for late adolescents. Journal of Family Issues, 29(6), 806–827. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X07311222

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. Guilford Press.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2019). Attachment orientations and emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.006

Millings, A., Walsh, J., Hepper, E. G., O'Brien, M., & Howe, D. (2012). Good partner, good parent: Caregiving mediates the link between romantic attachment and parenting style. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39, 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167212468333

Monaghan, M., Horn, I. B., Alvarez, V., Cogen, F. R., & Streisand, R. (2012). Authoritative parenting, parenting stress, and self-Care in pre-Adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 19(3), 255–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-011-9284-x

Muris, P., Meesters, C., & Van Brakel, A. (2003). Assessment of anxious rearing behaviors with a modified version of “Egna Minnen Bestra ¨ffende Uppfostran” questionnaire for children. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 25, 229–237. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025894928131

Mercer, N., Crocetti, E., Meeus, W., & Branje, S. (2017). Examining the relation between adolescent social anxiety, adolescent delinquency (abstention), and emerging adulthood relationship quality. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 30(4), 428–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2016.1271875

Nesi, J., Choukas-Bradley, S., & Prinstein, M. J. (2018). Transformation of adolescent peer relations in the social media context: Part 1-A theoretical framework and application to dyadic peer relationships. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 21(3), 267–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-018-0261-x

Newman, B. M., & Newman, P. R. (2020). Theories of adolescent development. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2017-0-03324-4

Orth, U. (2018). The family environment in early childhood has a long-term effect on self-esteem: A longitudinal study from birth to age 27 years. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114(4), 637–655. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000143

Quchani, M., Haji Arbabi, F., & Sabur Smaeili, N. (2021). A comparison of the effectiveness of Clark and ACT parenting training on improving the emotional-behavioral problems of the child with divorced single mothers. Learning and Motivation, 76, 101759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lmot.2021.101759

Patock-Peckham, J. A., & Morgan-Lopez, A. A. (2009). The gender-specific mediational pathways between parenting styles, neuroticism, pathological reasons for drinking, and alcohol-related problems in emerging adulthood. Addictive Behaviors, 34(3), 312–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.017

Pellerin, L. A. (2005). Applying Baumrind's parenting typology to high schools: Toward a middle-range theory of authoritative socialization. Social Science Research, 34(2), 283–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2004.02.003

Pinquart, M., & Gerke, D. C. (2019). Associations of parenting styles with self-esteem in children and adolescents: A Meta-analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 2017–2035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01417-5

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.40.3.879

Ravens-Sieberer, U., Karow, A., Barthel, D., & Klasen, F. (2014). How to assess quality of life in child and adolescent psychiatry. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 16(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2014.16.2/usieberer

Righy, C., Rosa, R. G., da Silva, R. T. A., et al. (2019). Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in adult critical care survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical Care, 23, 213. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-019-2489-3

Ripardo Teixeira, R. C., Piccoli Ferreira, J. H. B., & Howat-Rodrigues, A. B. C. (2019). Collins and Read revised adult attachment scale (RAAS) validity evidences. Porto Alegre, 50(2), e29567. https://doi.org/10.15448/1980-8623.2019.2.29567

Roelofs, J., Meesters, C., & Muris, P. (2008). Correlates of self-reported attachment (in)security in children: The role of parental romantic attachment status and rearing behaviors. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 17, 555–566. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-007-9174-x

Schindler, A. (2019). Attachment and substance use disorders-theoretical models, empirical evidence, and implications for treatment. Frontal Psychiatry, 10, 727. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00727

Shahsavari, M. (2012). A general overview on parenting styles and its effective factors. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 6(8), 139–142.

Sigelman, C. K., & Rider, E. A. (2008). Life-span human development (6th. ed.). Wadsworth.

Sroufe, L. A. (1985). Attachment classification from the perspective of infant-caregiver relationships and infant temperament. Child Development, 56(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130168

Stark, S. (2015). Emotional abuse. In In book: Psychology and behavioral HealthEdition: 4thChapter: Volume 1 essay: Emotional AbusePublisher. Salem Press at Greyhouse PublishingEditors: Paul Moglia.

Stein, M. D., Conti, M. T., Kenney, S., Anderson, B. J., Flori, J. N., Risi, M. M., & Bailey, G. L. (2017). Adverse childhood experience effects on opioid use initiation, injection drug use, and overdose among persons with opioid use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 179, 325–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.07.007

Styron, T., & Janoff-Bulman, R. (1997). Childhood attachment and abuse: Long-term effects on adult attachment, depression and conflict resolution. Child Abuse & Neglect, 21(10), 1015–1023. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00062-8

Ungar, M. (2004). The importance of parents and other caregivers to the resilience of high-risk adolescents. Family Process, 43(1), 23–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.04301004.x

Unger, J. A. M., & De Luca, R. V. (2014). The relationship between childhood physical abuse and adult attachment styles. Journal of Family Violence, 29, 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-014-9588-3

Wang, Y., Yang, Z., Zhang, Y., Wang, F., Liu, T., & Xin, T. (2019). The effect of social-emotional competency on child development in Western China. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1282. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01282

Vrolijk-Bosschaart, T. F., Brilleslijper-Kater, S. N., Verlinden, E., Widdershoven, G. A. M., Teeuw, A. H., Voskes, Y., van Duin, E. M., Verhoeff, A. P., de Leeuw, M., Roskam, M. J., Benninga, M. A., & Lindauer, R. J. L. (2019). A descriptive mixed-methods analysis of sexual behavior and knowledge in very Young children assessed for sexual abuse: The ASAC study. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2716. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02716

Yaffe, Y. (2021). Identifying the parenting styles and practices associated with high and low self-esteem amongst middle to late adolescents from Hebrew-literate Bedouin families. Current Psychology, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01723-6

Young, J. C., & Widom, C. S. (2014). Long-term effects of child abuse and neglect on emotion processing in adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(8), 1369–1381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.03.008

Yun, B. X., Thing, T. S., & Hsoon, N. C. (2019). A quantitative study of relationship between parenting style and adolescent’s self-esteem. Advances in Social Sciences, Education and Humanities Research, 84, 441–446. https://doi.org/10.2991/acpch-18.2019.103

Zuquetto, C. R., Opaleye, E. S., Feijo, M. R., Amato, T. C., Ferri, C. P., & Noto, A. R. (2019). Contributions of parenting styles and parental drunkenness to adolescent drinking. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 41(6), 511–517. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2018-0041

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were by the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the present study.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest has been stated by the authors of the article.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest among authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bahmani, T., Naseri, N.S. & Fariborzi, E. Relation of parenting child abuse based on attachment styles, parenting styles, and parental addictions. Curr Psychol 42, 12409–12423 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02667-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02667-7